What is the name of a common still life of the 17th century? Exquisite Dutch still life - masterpieces of a quiet life

Despite the fact that the name of the genre translated from French means “dead nature”. Why, in the mouths of the Dutch, did compositions of inanimate objects, colorfully displayed on canvas, signify life? Yes, these images were so bright, reliable and expressive that even the most inexperienced connoisseurs admired the realism and tangibility of the details. But it's not only that.

Dutch still life is an attempt to talk about how alive and closely every object is, every particle of this world is woven into the complex world of man and participates in it. Dutch masters created ingenious compositions and were able to so accurately depict the shape, color tints, volume and texture of objects that they seemed to store the dynamics of human actions. Here is a pen that has not yet cooled down from the poet’s hand with a glittering drop of ink, here is a cut pomegranate, dripping with ruby juice, and here is a loaf bitten and thrown onto a crumpled napkin... And at the same time, this is an invitation to enchantedly admire and enjoy the splendor and diversity of nature.

Themes and picturesque images

Dutch still life is inexhaustible in its abundance of themes. Some painters shared a passion for flowers and fruits, others specialized in the rough verisimilitude of pieces of meat and fish, others lovingly created kitchen utensils on canvas, and others devoted themselves to the theme of science and art.

Dutch still life from the early 17th century is distinguished by its commitment to symbolism. Items are strictly specific place and meaning. The apple in the center of the image tells the story of the fall of the first man, while the bunch of grapes covering it tells the story of the atoning sacrifice of Christ. An empty shell, which once served as a home for a sea mollusk, speaks of the frailty of life, drooping and dried flowers - of death, and a butterfly fluttering out of a cocoon heralds resurrection and renewal. Balthasar Ast writes in this manner.

Artists of the new generation have proposed a slightly different Dutch still life. Painting “breathes” with the elusive charm hidden in ordinary things. A half-filled glass, serving items scattered on the table, fruits, a cut pie - the authenticity of the details is perfectly conveyed by color, light, shadows, highlights and reflections, convincingly associated with the texture of fabric, silver, glass and food. These are the paintings of Pieter Claes Heda.

By the early 18th century, Dutch still life gravitated toward an impressive aesthetic of detail. Elegant porcelain bowls with gilding, goblets made of intricately curled shells, and fruits exquisitely arranged on a dish reign here. It is impossible to look at the canvases of Willem Kalf or Abraham van Beyeren without fading. Dutch is becoming unusually widespread, captured by the hand of a master, speaking in a special, sensual language and communicating painting harmony and rhythm. The lines, weaves and shades of stems, buds, open inflorescences present in the still life seem to create a complex symphony, forcing the viewer not only to admire, but also to excitedly experience the incomprehensible beauty of the world.

Along with landscape painting, still life, which was distinguished by its intimate character, became widespread in 17th-century Holland. Dutch artists chose a wide variety of objects for their still lifes, knew how to arrange them perfectly, and reveal the characteristics of each object and its inner life, inextricably linked with human life.

The 17th century Dutch painters Pieter Claes (c. 1597 - 1661) and Willem Heda (1594-1680/1682) painted numerous versions of “breakfasts”, depicting hams, ruddy buns, blackberry pies, fragile glass goblets, half filled with wine, with amazing skill conveying the color, volume, texture of each item. The recent presence of a person is noticeable in the disorder, the randomness of the arrangement of things that have just served him. But this disorder is only apparent, since the composition of each still life is strictly thought out and found. A restrained grayish-golden, olive tonal palette unites objects and gives a special sonority to those pure colors that emphasize the freshness of a freshly cut lemon or the soft silk of a blue ribbon.

Over time, the “breakfasts” of the still life masters, painters Claes and Heda give way to the “desserts” of the Dutch artists Abraham van Beyeren (1620/1621-1690) and Willem Kalf (1622-1693). Beyeren's still lifes are strict in composition, emotionally rich, and colorful. Throughout his life, Willem Kalf painted in a free manner and democratic “kitchens” - pots, vegetables and aristocratic still lifes in the selection of exquisite precious objects, full of restrained nobility, like silver vessels, cups, shells saturated with the internal combustion of colors.

In its further development, still life follows the same path as all Dutch art, losing its democracy, its spirituality and poetry, its charm. Still life turns into decoration for the home of high-ranking customers. For all their decorativeness and skillful execution, the late still lifes anticipate the decline of Dutch painting.

Social degeneration and the well-known aristocratization of the Dutch bourgeoisie in the last third of the 17th century give rise to a tendency towards convergence with the aesthetic views of the French nobility and lead to idealization artistic images, their grinding. Art is losing connections with the democratic tradition, losing its realistic basis and entering a period of long-term decline. Severely exhausted in the wars with England, Holland is losing its position as a great trading power and a major artistic center.

The work of Frans Hals and the Dutch portrait of the first half XVII century.

Frans Hals(Dutch Frans Hals, IPA: [ˈfrɑns ˈɦɑls]) (1582/1583, Antwerp - 1666, Haarlem) - an outstanding portrait painter of the so-called golden age of Dutch art.

- 1 Biography

- 2 Interesting Facts

- 3 Gallery

- 4 Notes

- 5 Literature

- 6 Links

Biography

"Family portrait of Isaac Massa and his wife"

Hals was born around 1582-1583 to the Flemish weaver François Frans Hals van Mechelen and his second wife Adriantje. In 1585, after the fall of Antwerp, the Hals family moved to Haarlem, where the artist lived his entire life.

In 1600-1603, the young artist studied with Karel van Mander, although the influence of this representative of Mannerism is not traced in Hals’ subsequent works. In 1610, Hals became a member of the Guild of St. Luke and begins to work as a restorer at the city municipality.

Hals created his first portrait in 1611, but fame came to Hals after creating the painting “Banquet of the officers of the rifle company of St. George" (1616).

In 1617 he married Lisbeth Reyners.

“The early style of Hals was characterized by a predilection for warm tones and clear modeling of forms using heavy, dense strokes. In the 1620s, Hals, along with portraits, painted genre scenes and compositions on religious themes"("Evangelist Luke", "Evangelist Matthew", circa 1623-1625)".

"Gypsy" Louvre, Paris

In the 1620-1630s. Hals painted a number of portraits depicting representatives bursting with vital energy common people(“Jester with a Lute”, 1620-1625, “Merry Drinking Companion”, “Malle Babbe”, “Gypsy”, “Mulatto”, “Fisherman Boy”; all - around 1630).

The only portrait in full height is the "Portrait of Willem Heythuissen" (1625-1630).

“During the same period, Hals radically reformed the group portrait, breaking with conventional systems of composition, introducing elements of life situations into the works, ensuring a direct connection between the picture and the viewer (“Banquet of officers of the St. Adrian rifle company,” circa 1623-27; “Banquet of rifle officers company of St. George", 1627, "Group portrait of the rifle company of St. Adrian", 1633; "Officers of the rifle company of St. George", 1639). Not wanting to leave Haarlem, Hals refused orders if this meant going to Amsterdam. The only group portrait he began in Amsterdam had to be completed by another artist.

In the years 1620-1640, the time of his greatest popularity, Hals painted many double portraits of married couples: the husband on the left portrait, and the wife on the right. The only painting where the couple are depicted together is “Family Portrait of Isaac Massa and his Wife” (1622).

"Regents of the Home for the Elderly"

In 1644 Hals became president of the Guild of St. Luke. In 1649 he painted a portrait of Descartes.

“Psychological characteristics deepen in portraits of the 1640s. ("The Regents of St. Elizabeth's Hospital", 1641, portrait of a young man, circa 1642-50, "Jasper Schade van Westrum", circa 1645); In the coloring of these works, a silver-gray tone begins to predominate. Hals's later works were performed in a very free manner and were designed in a spare color scheme, built on contrasts of black and white tones (“Man in black clothes", around 1650-52, "V. Cruz", around 1660); some of them showed a feeling of deep pessimism (“The Regents of the Home for the Aged,” “The Regents of the Home for the Aged,” both 1664).”

“In his old age, Hals stopped receiving orders and fell into poverty. The artist died in a Haarlem almshouse on August 26, 1666.”

The largest collection of the artist's paintings is owned by the Hals Museum in Haarlem.

The founder of the Dutch realistic portrait was Frans Hals (Hals) (about 1580-1666), whose artistic legacy, with its sharpness and power of capturing the inner world of a person, goes far beyond the national Dutch culture. An artist with a broad worldview, a brave innovator, he destroyed the canons of class (noble) portraiture that had emerged before him in the 16th century. He was not interested in the person depicted according to his social status in a majestically solemn pose and ceremonial costume, but a person in all his natural essence, character, with his feelings, intellect, emotions. In Hals's portraits all layers of society are represented: burghers, riflemen, artisans, representatives of the lower classes, his special sympathies are on the side of the latter, and in their images he showed the depth of a powerful, full-blooded talent. The democracy of his art is due to connections with the traditions of the era of the Dutch revolution. Hals portrayed his heroes without embellishment, with their unceremonious morals and powerful love of life. Hals expanded the scope of the portrait with the introduction plot elements, capturing those portrayed in action, in a specific life situation, emphasizing facial expressions, gestures, poses, instantly and accurately captured. The artist sought emotional intensity and vitality of the characteristics of those portrayed, conveying their irrepressible energy. Hals not only reformed individual commissioned and group portraits, but was the creator of a portrait bordering on the everyday genre.

Hals was born in Antwerp, then moved to Haarlem, where he lived all his life. He was a cheerful, sociable person, kind and carefree. Creative face The Khalsa was formed by the early 20s of the 17th century. Group portraits of officers of the St. George's rifle company (1627, Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum), and the St. Adrian's rifle company (1633, ibid.) gained him wide popularity. Strong, energetic people who took an active part in the liberation struggle against the Spanish conquerors are presented during the feast. A cheerful mood with a touch of humor unites officers of different characters and manners. There is no main character here. All those present are equal participants in the celebration. Hals overcame the purely external connection of characters characteristic of the portraits of his predecessors. The unity of the asymmetrical composition is achieved by lively communication, relaxed freedom of arrangement of figures, united by a wave-like rhythm.

The artist's energetic brush sculpts the volumes of forms with brilliance and strength. Streams of sunlight slide across faces, sparkle in lace and silk, sparkle in glasses. The colorful palette, dominated by black suits and white collars, is enlivened by the sonorous golden-yellow, purple, blue and pink officer's baldrics. Full of self-esteem and at the same time free and relaxed, gesticulating, the Dutch burghers appear in the portraits of Hals, conveying an instantly captured state. An officer in a wide-brimmed hat, arms akimbo, smiles provocatively (1624, London, Wallace Collection). They are captivated by the naturalness and liveliness of the pose, the sharpness of the characteristics, highest craftsmanship using the contrast of white and black in painting.

Hals's portraits are varied in themes and images. But those portrayed are united by common features: integrity of nature, love of life. Hals is a painter of laughter, a cheerful, infectious smile. With sparkling joy, the artist brings to life the faces of representatives of the common people, visitors to taverns, and street urchins. His characters do not withdraw into themselves; they turn their gazes and gestures towards the viewer.

The image of “The Gypsy” (circa 1630, Paris, Louvre) is filled with a freedom-loving breath. Hals admires the proud position of her head in a halo of fluffy hair, her seductive smile, the perky sparkle of her eyes, her expression of independence. The vibrating outline of the silhouette, sliding rays of light, running clouds, against which the gypsy is depicted, fill the image with the thrill of life. The portrait of Malle Babbe (early 1630s, Berlin - Dahlem, Picture Gallery), an innkeeper, not accidentally nicknamed the “Harlem Witch,” develops into a small genre scene. An ugly old woman with a burning, cunning gaze, turning sharply and grinning widely, as if answering one of the regulars of her tavern. An ominous owl looms in a gloomy silhouette on her shoulder. The artist’s sharpness, vision, gloomy strength and vitality of the image he created is striking. The asymmetry of the composition, the dynamics, and the richness of the angular strokes enhance the anxiety of the scene.

By the mid-17th century, the shifts that had taken place in Dutch society were clearly visible; As the position of the bourgeoisie, which has lost contact with the masses, strengthens in it, it acquires an increasingly conservative character. The attitude of bourgeois clients towards realist artists has changed. Hals also lost his popularity, whose democratic art became alien to the degenerating bourgeoisie, which rushed after aristocratic fashion.

The life-affirming optimism of the master was replaced by deep thought, irony, bitterness, and skepticism. His realism became more psychologically in-depth and critical, his skill more refined and perfect. The color of the Khalsa also changed, acquiring greater restraint; in the predominant silver-gray, cold tonal range, among black and white, small, accurately found spots of pinkish or red color acquire a special sonority. The feeling of bitterness and disappointment is palpable in “Portrait of a Man in Black Clothes” (circa 1660, St. Petersburg, Hermitage), in which the subtlest colorful shades of the face are enriched and come to life next to the restrained, almost monochrome black and white tones.

Hals's highest achievement is his last group portraits of the regents and regents (trustees) of a nursing home, executed in 1664, two years before the death of the artist, who ended his life alone in the shelter. Full of vanity, cold and devastated, power-hungry and arrogant, the old trustees sitting at the table from the group “Portrait of the Regents of a Home for the Elderly” (Harlem, Frans Hals Museum. The hand of the old artist unerringly accurately applies free, swift strokes. The composition has become calm and strict. Sparsity of space , the arrangement of the figures, the even diffused light, equally illuminating all those depicted, contribute to focusing attention on the characteristics of each of them. The color scheme is laconic with a predominance of black, white and gray tones. The late portraits of Hals stand next to the most remarkable creations of world portraiture: with their psychologism they are close to the portraits of the greatest of Dutch painters - Rembrandt, who, like Hals, experienced his lifetime fame by coming into conflict with the bourgeois elite of Dutch society.

Frans Hals was born around 1581 in Antwerp into a weaver's family. As a young man, he came to Haarlem, where he lived almost constantly until his death (in 1616 he visited Antwerp, and in the mid-1630s - Amsterdam). Little is known about Hulse's life. In 1610 he entered the Guild of St. Luke, and in 1616 he entered the chamber of rhetoricians (amateur actors). Very quickly Hals became one of the most famous portrait painters in Haarlem.

In the XV–XVI centuries. in the painting of the Netherlands there was a tradition of painting portraits only of representatives ruling circles, famous people and artists. Hals's art is deeply democratic: in his portraits we can see an aristocrat, a wealthy citizen, an artisan, and even a person from the very bottom. The artist does not try to idealize those depicted; the main thing for him is their naturalness and uniqueness. His nobles behave as relaxed as representatives of the lower strata of society, who in Khals’s paintings are depicted as cheerful people who are not devoid of self-esteem.

Group portraits occupy a large place in the artist’s work. The best works of this genre were portraits of officers of the St. George rifle company (1627) and the St. Adrian rifle company (1633). Each character in the paintings has its own distinct personality, and at the same time, these works are distinguished by their integrity.

Hals also painted commissioned portraits depicting wealthy burghers and their families in relaxed poses (“Portrait of Isaac Massa,” 1626; “Portrait of Hethuisen,” 1637). Hals’s images are lively and dynamic; it seems that the people in the portraits are talking to an invisible interlocutor or addressing the viewer.

Representatives of the popular environment in Khals’s portraits are distinguished by their vivid expressiveness and spontaneity. In the images of street boys, fishermen, musicians, and tavern visitors, one can feel the author’s sympathy and respect. His “Gypsy” is remarkable. The smiling young woman seems surprisingly alive, her sly gaze directed at her interlocutor, invisible to the audience. Hals does not idealize his model, but the image of a cheerful, disheveled gypsy delights with its perky charm.

Very often, Hulse's portraits include elements of a genre scene. These are the images of children singing or playing musical instruments (“Singing Boys”, 1624–1625). The famous “Malle Babbe” (early 1630s) was performed in the same spirit, representing a well-known tavern owner in Haarlem, whom visitors called the Haarlem Witch behind her back. The artist almost grotesquely depicted a woman with a huge beer mug and an owl on her shoulder.

In the 1640s. The country is showing signs of a turning point. Only a few decades have passed since the victory of the revolution, and the bourgeoisie has already ceased to be a progressive class based on democratic traditions. The truthfulness of Hulse's paintings no longer attracts wealthy clients who want to see themselves in portraits better than they really are. But Hulse did not abandon realism, and his popularity plummeted. Notes of sadness and disappointment appear in the painting of this period (“Portrait of a Man in a Wide-brimmed Hat”). His palette becomes stricter and calmer.

At the age of 84, Hulse created two of his masterpieces: group portraits of regents (trustees) and regents of a nursing home (1664). These latest works by the Dutch master are distinguished by their emotionality and strong individuality of images. The images of the regents - old men and women - emanate sadness and death. This feeling is also emphasized by the color scheme in black, gray and white.

Hals died in 1666 in deep poverty. His truthful, life-affirming art has had big influence on many Dutch artists.

Painting by Rembrandt.

| Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch painter, draftsman and etcher. Rembrandt's work, imbued with the desire for a deeply philosophical understanding of life, the inner world of man with all its richness emotional experiences, marks the pinnacle of development of Dutch art of the 17th century, one of the peaks of world artistic culture. Rembrandt's artistic heritage is distinguished by its exceptional diversity: he painted portraits, still lifes, landscapes, genre scenes, paintings of historical, biblical, mythological themes, Rembrandt was consummate master drawing and etching. After a short study at the University of Leiden (1620), Rembrandt decided to devote himself to art and studied painting with J. van Swanenburch in Leiden (circa 1620-1623) and P. Lastman in Amsterdam (1623); in 1625-1631 he worked in Leiden. Rembrandt's paintings of the Leiden period are marked by a search for creative independence, although the influence of Lastman and the masters of Dutch Caravaggism is still noticeable in them (“Bringing to the Temple”, circa 1628-1629, Kunsthalle, Hamburg). In the paintings “The Apostle Paul” (circa 1629-1630, National Museum, Nuremberg) and “Simeon in the Temple” (1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague), he first used chiaroscuro as a means of enhancing the spirituality and emotional expressiveness of images. During these same years, Rembrandt worked hard on the portrait, studying the facial expressions of the human face. In 1632, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, where he soon married the wealthy patrician Saskia van Uylenburgh. The 1630s are a period of family happiness and enormous artistic success for Rembrandt. The painting “The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Tulp” (1632, Mauritshuis, The Hague), in which the artist innovatively solved the problem of a group portrait, giving the composition a vital ease and uniting those portrayed in a single action, brought Rembrandt wide fame. In portraits painted for numerous orders, Rembrandt van Rijn carefully conveyed facial features, clothing, and jewelry (the painting “Portrait of a Burgrave,” 1636, Dresden Gallery). | ||||

| In the 1640s, a conflict was brewing between Rembrandt’s work and the limited aesthetic demands of his contemporary society. It clearly manifested itself in 1642, when the painting “ The night Watch” (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) caused protests from customers who did not accept the master’s main idea - instead of a traditional group portrait, he created a heroically upbeat composition with a scene of a performance by the guild of shooters at an alarm signal, i.e. essentially a historical picture that evokes memories of the liberation struggle of the Dutch people. The influx of orders for Rembrandt is dwindling, his life circumstances are overshadowed by the death of Saskia. Rembrandt's work is losing its external effectiveness and its previously inherent notes of major. He writes calm biblical and genre scenes filled with warmth and intimacy, revealing subtle shades of human experiences, feelings of spiritual, family closeness (“David and Jonathan”, 1642, “Holy Family”, 1645, both in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg). |

| All higher value both in painting and in Rembrandt’s graphics, the finest play of light and shadow is acquired, creating a special, dramatic, emotionally intense atmosphere (the monumental graphic sheet “Christ Healing the Sick” or “The Hundred Guilder Sheet”, circa 1642-1646; full of air and light dynamics landscape “Three Trees”, etching, 1643). The 1650s, filled with difficult life trials for Rembrandt, ushered in the period of the artist’s creative maturity. Rembrandt increasingly turns to the portrait genre, depicting those closest to him (numerous portraits of Rembrandt’s second wife Hendrikje Stoffels; “Portrait of an Old Woman”, 1654, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; “Son Titus Reading”, 1657, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). |

| In the mid-1650s, Rembrandt acquired mature painting skills. The elements of light and color, independent and even partly opposite in the artist’s early works, now merge into a single interconnected whole. The hot red-brown, now flaring up, now fading, quivering mass of luminous paint enhances the emotional expressiveness of Rembrandt’s works, as if warming them with a warm human feeling. In 1656, Rembrandt was declared an insolvent debtor, and all his property was sold at auction. He moved to the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam, where he spent the rest of his life in extremely cramped circumstances. Rembrandt's biblical compositions in the 1660s sum up his thinking about meaning. human life. In episodes expressing the clash of dark and light in the human soul (“Assur, Haman and Esther”, 1660, Pushkin Museum, Moscow; “The Fall of Haman” or “David and Uriah”, 1665, State Hermitage, St. Petersburg), a rich warm palette , flexible impasto style of painting, intense play of shadow and light, complex texture of the colorful surface serve to reveal complex collisions and emotional experiences, affirm the triumph of good over evil. |

| Imbued with severe drama and heroism historical picture“Conspiracy of Julius Civilis” (“Conspiracy of the Batavians”, 1661, fragment preserved, National Museum, Stockholm). IN Last year life Rembrandt created his main masterpiece- the monumental canvas “The Return of the Prodigal Son” (circa 1668-1669, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg), which embodied all the artistic, moral and ethical issues late creativity artist. With amazing skill, he recreates in him a whole range of complex and deep human feelings, subjugates artistic media revealing the beauty of human understanding, compassion and forgiveness. Climax The transition from tension of feelings to the resolution of passions is embodied in sculpturally expressive poses, spare gestures, in the emotional structure of color, flashing brightly in the center of the picture and fading in the shadowed space of the background. The great Dutch painter, draftsman and etcher Rembrandt van Rijn died on October 4, 1669 in Amsterdam. The influence of Rembrandt's art was enormous. It affected the work not only of his immediate students, of whom Carel Fabricius came closest to understanding the teacher, but also on the art of every more or less significant Dutch artist. Rembrandt's art had a profound impact on the development of the entire world realistic art subsequently. |

Rembrandt Harmens van Rijn(Dutch Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn[ˈrɛmbrɑnt ˈɦɑrmə(n)soːn vɑn ˈrɛin], 1606-1669) - Dutch artist, draftsman and engraver, great master of chiaroscuro, largest representative the golden age of Dutch painting. He managed to embody in his works the entire spectrum of human experiences with such an emotional intensity that had never been known before art. Rembrandt's works, extremely diverse in genre, reveal to the viewer a timeless spiritual world human experiences and feelings.

- 1 Biography

- 1.1 Years of apprenticeship

- 1.2 Influence of Lastman and the Caravaggists

- 1.3 Workshop in Leiden

- 1.4 Developing your own style

- 1.5 Success in Amsterdam

- 1.6 Dialogue with Italians

- 1.7 "Night Watch"

- 1.8 Transition period

- 1.9 Late Rembrandt

- 1.10 Recent works

- 2 Attribution problems

- 3 Rembrandt's students

- 4 Posthumous fame

- 5 At the movies

- 6 Notes

- 7 Links

Biography

Years of apprenticeship

Rembrandt Harmenszoon (“son of Harmen”) van Rijn was born on July 15, 1606 (according to some sources, in 1607) in the large family of the wealthy mill owner Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn in Leiden. Even after the Dutch Revolution, the mother's family remained faithful to the Catholic religion.

"Allegory of Music" of 1626 - an example of Lastman's influence on the young Rembrandt

In Leiden, Rembrandt attended the Latin school at the university, but showed the greatest interest in painting. At the age of 13, he was sent to study fine art with the Leiden historical painter Jacob van Swanenburch, a Catholic by faith. Rembrandt's works of this period have not been identified by researchers, and the question of Swanenbuerch's influence on the development of his creative style remains open: too little is known today about this Leiden artist.

In 1623, Rembrandt studied in Amsterdam with Pieter Lastman, who had trained in Italy and specialized in historical, mythological and biblical subjects. Returning to Leiden in 1627, Rembrandt, together with his friend Jan Lievens, opened his own workshop and began to recruit students. Within a few years he had gained considerable fame.

Today we will meet one of the best masters Dutch luxurious still life BY WILLEM KALF 1619-1693

Willem Kalf was the sixth child in the family of a wealthy Rotterdam cloth merchant and member of the Rotterdam city council. Willem's father died in 1625, when the boy was 6 years old. The mother continued the family business, but without much success.

There is no information about which artist Kalf studied with; perhaps his teacher was Hendrik Poth from Haarlem, where the Kalfs' relatives lived. Shortly before the death of his mother in 1638, Willem left his hometown and moved to The Hague, and then in 1640-41. settled in Paris.

There, thanks to their " peasant interiors", written in the Flemish tradition, close to the work of David Teniers and other artists of the 17th century, Kalf quickly gained recognition.

On its rustic interiors human figures were rather in the background, and all the viewer’s attention was concentrated on well-lit, colorful and skillfully laid out fruits, vegetables and various household items.

Here he created new uniform an artfully grouped still life with expensive, ornate objects ( for the most part bottles, plates, glasses) made of light-reflecting materials - gold, silver, tin or glass. This artist’s skill reached its peak in the Amsterdam period of his work in the mesmerizing “ LUXURY STILL LIFE»

Still life with a drinking horn belonging to the Guild of Archers of St. Sebastian, a lobster and glasses - Willem Kalf. Around 1653.

This still life is one of the most famous.

It was created in 1565 for the guild of Amsterdam archers. When the artist worked on this still life, the horn was still in use during guild meetings.

This wonderful vessel is made of buffalo horn, the fastening is made of silver, if you look closely, you can see miniature figures of people in the design of the horn - this scene tells us about the suffering of St. Sebastian, patron of archers.

The tradition of adding peeled lemon to Rhine wine came from the fact that the Dutch considered this type of wine too sweet.

The lobster, the wine horn with its sparkling silver filigree rim, the clear glasses, the lemon and the Turkish carpet are rendered with such amazing care that the illusion arises that they are real and can be touched with your hand.

The placement of each item is chosen with such care that the group as a whole forms a harmony of color, shape and texture. Warm light enveloping objects gives them the dignity of precious jewelry, and their rarity, splendor and whimsicality reflect the refined tastes of Dutch collectors in the 17th century - a time when still life paintings were extremely popular.

Still life with a jug and fruit. 1660

In 1646, Willem Kalf returned to Rotterdam for some time, then moved to Amsterdam and Hoorn, where in 1651 he married Cornelia Plouvier, daughter of a Protestant minister.

Cornelia was a famous calligrapher and poetess, she was friends with Constantijn Huygens, the personal secretary of the three stadtholders of the young Dutch Republic, a respected poet and probably the most experienced expert on world theater and musical art of its time.

In 1653, the couple moved to Amsterdam, where they had four children. Despite his wealth, Kalf never acquired his own home.

Still life with a teapot.

During the Amsterdam period, Kalf began to include exotic objects in his perfect still lifes: Chinese vases, shells and hitherto unseen tropical fruits - half-peeled oranges and lemons. These items were brought to the Netherlands from America; they were favorite objects of prestige for the wealthy burghers, who flaunted their wealth.

Still life with nautilus and Chinese bowl.

The Dutch loved and understood a good interior, a comfortable table setting, where everything you need is at hand, convenient utensils - in the material world that surrounds a person.

In the center we see an elegant nautilus cup made from a shell, as well as a beautiful Chinese vase. On the outside it is decorated with eight relief figures representing the eight immortals in Taoism, the cone on the lid is the outline of a Buddhist lion.

This still life is complemented by a traditional Kalfa Persian carpet and a lemon with a thin spiral of peel.

The pyramid of objects drowns in a haze of twilight, sometimes only light reflections indicate the shape of things. Nature created a shell, a craftsman turned it into a goblet, an artist painted a still life, and we enjoy all this beauty. After all, being able to see beauty is also a talent.

Still life with a glass goblet and fruit. 1655.

Like all still lifes of that time, Kalf’s creations were intended to express the iconographic idea of frailty - “memento mori” (“remember death”), to serve as a warning that all things, living and inanimate, are ultimately transitory.

Still life with fruit and a nautilus cup.1660g

For Kalf, however, something else was important. All his life he had a keen interest in the play of light and the effects of light on various materials, starting with the texture of woolen carpets, the bright shine of metal objects made of gold, silver or tin, the soft glow of porcelain and multi-colored shells, and ending with the mysterious shimmer of the edges of the most beautiful glasses and vases in the Venetian style.

Still life with a Chinese tureen.

Dessert. Hermitage.

Before entering the Hermitage in 1915, the painting “Dessert” was part of the collection of the famous Russian geographer and traveler P. P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, a great connoisseur and lover of Dutch and Flemish art.

A bright beam of light pulls out from the semi-darkness a bowl of fruit, a peach on a silver tray and a crumpled white tablecloth. The glass and silver goblets still reflect the light, and the thin flute glass filled with wine almost blends into the background.

The artist masterfully conveys the texture of each item: a glass, a painted faience plate, a gilded goblet, an oriental carpet, a snow-white napkin. The painting shows the strong influence that Rembrandt’s painting had on Kalf: objects are shown against a dark background, bright light as if it revives them, enveloping them in the warmth of golden rays.

Still Life with a Porcelain Vase, Silver-gilt Ewer, and Glasses

Pronk Still Life with Holbein Bowl, Nautilus Cup, Glass Goblet and Fruit Dish

The composition of Kalf's still lifes, thought out to the smallest detail, is ensured not only by specific rules, but also by unique and complex directionSveta.

Valuable objects—cut goblets, often half filled with wine—appear from the darkness of the background gradually, after some time. Often their shape is only surprisingly guessed in the reflection of rays of light. No one except Kalf managed to show the light penetrating through the nautilus shell so realistically. Absolutely rightly, Kalf is called the “Vermeer of still life painting,” and in some places Kalf surpassed him.

Since 1663 Kalf wrote less, he took up the art trade and became a sought-after art expert.

Willem Kalf died at the age of 74, injured in a fall on the way home while returning from a visit.

Thanks to his unique visual abilities, coupled with his excellent education and extensive knowledge of the natural sciences, he significantly expanded the illusionistic possibilities of still life. His creations are unsurpassed examples of this art.

Dutch artists achieved great achievements in the creation of art realistic direction, naturally depicting reality, precisely because such art was in demand in Dutch society.

For Dutch artists, easel painting was important in art. The canvases of the Dutch of this time do not have the same dimensions as the works of Rubens, and preferably solve not monumental-decorative tasks; the clients of the Dutch painters were envoys of the ruling leadership of the organization, but also the second class - burghers and artisans.

One of the main concerns of Dutch painters was man and the environment. The main place in Dutch painting was the everyday genre and portrait, landscape and still life. The better the painters depicted the natural world impartially and deeply, the more numerous the significant and demanding subjects of their work were.

Dutch painters produced works for sale and sold their paintings at fairs. Their works were bought mainly by people from the upper strata of society - rich peasants, artisans, merchants, and factory owners. Ordinary people could not afford this, and looked at and admired the paintings with pleasure. The general disposition of art in the heyday of the 17th century, deprived such powerful consumers as the court, the nobility and the church.

The works were produced in a small format, designed to fit modest and not large-sized furnishings in Dutch houses. One of the favorite pastimes of the Dutch was easel painting, since it was receptive to reflect the reality of actions with great reliability and in a variety of ways. The paintings of the Dutch depict the reality of their country, close to them; they wanted to see what was very familiar to them - the sea and ships, the nature of their land, their home, the activities of everyday life, the things that surrounded them everywhere.

One important attraction to learning environment appeared in Dutch painting in such natural forms and with such clear continuity as nowhere else in Dutch art of these times. In connection with this, the depth of its scale is also connected: portraits and landscapes, still lifes and everyday genres were formed in it. A few of them, still life and everyday painting, were the first to emerge in mature forms in Holland and flourished to such an extent that they became the only example of this genre.

In the first two decades, the main tendency of the search for the main Dutch artists, counteracting the correct artistic trends, is clearly manifested - the desire for a faithful reproduction of reality, for the accuracy of its expression. It was not by coincidence that the artists of Holland were attracted by the art of Caravaggio. The work of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggists - G. Honthorst, H. Terbruggen, D. Van Baburen - showed an impact on Dutch artistic culture.

Dutch painters in the 20s and 30s of the 17th century created the main type of suitable small-figure painting, which depicts scenes from the life of simple peasants and their everyday activities. In the 40s - 50s household painting is one of the main genres, the authors of which in history have acquired the name “little Dutch”, either because of the artlessness of the plot, or because of the small size of the paintings, or maybe for both. The images of peasants in the paintings are covered with traits of good-natured humor Adriana van Ostade. He was a democratic writer of everyday life and an entertaining storyteller. Jan Steen.

One of the major portrait painters of Holland, the founder of the Dutch realistic portrait was Franz Hals. He created his fame with group portraits of shooting guilds, in which he expressed the ideals of the young republic, feelings of freedom, equality, and camaraderie.

The pinnacle of creativity of Dutch realism is Harmens van Rijn Rembrandt, distinguished by its extraordinary vitality and emotionality, deep humanity of images, and great thematic breadth. He painted historical, biblical, mythological and everyday paintings, portraits and landscapes, and was one of the greatest masters of etching and drawing. But no matter what technique he worked with, the center of his attention was always the person, his inner world. He often found his heroes among the Dutch poor. In his works, Rembrandt combined strength and penetration psychological characteristics with exceptional mastery of painting, in which neat tones of chiaroscuro acquire the main importance.

During the first third of the 17th century, the views of the Dutch realistic landscape emerged, which flourished in the middle of the century. The landscape of the Dutch masters is not nature in general, as in the paintings of the classicists, but a national, specifically Dutch landscape: windmills, desert dunes, canals with boats gliding along them in the summer and with skaters in the winter. The artists sought to convey the atmosphere of the season, humid air and space.

Still life has developed prominently in Dutch painting and is distinguished by its small size and character. Peter Claes And Willem Heda most often they depicted so-called breakfasts: dishes with ham or pie on a relatively modestly served table. The recent presence of a person is palpable in the disorder and naturalness with which the things that have just served him are arranged. But this disorder is only apparent, since the composition of each still life is carefully thought out. In a skillful arrangement, objects are shown in such a way that one feels the inner life of things; it is not for nothing that the Dutch called still life “still leven” - “quiet life”, and not “nature morte” - “dead nature”.

Still life. Peter Claes and Willem Heda

Subtlety and truthfulness in recreating reality are combined by the Dutch masters with keen sense the beauty revealed in any of its phenomena, even the most inconspicuous and everyday. This feature of the Dutch artistic genius manifested itself, perhaps most clearly, in still life; it is no coincidence that this genre was a favorite in Holland.

The Dutch called still life "stilleven", which means "quiet life", and this word expresses incomparably more accurately the meaning that Dutch painters put into the depiction of things than "nature morte" - dead nature. IN inanimate objects they saw something special hidden life connected with a person’s life, with his way of life, habits, tastes. Dutch painters created the impression of natural “mess” in the arrangement of things: they showed a cut pie, a peeled lemon with the peel hanging in a spiral, an unfinished glass of wine, a burning candle, open book, - it always seems that someone touched these objects, just used them, the invisible presence of a person is always felt.

The leading masters of Dutch still life painting in the first half of the 17th century were Pieter Claes (1597/98-1661) and Willem Heda (1594-ca. 1680). A favorite theme of their still lifes is the so-called “breakfasts”. In "Breakfast with Lobster" by V. Kheda, the objects various shapes and materials - coffee pot, glass, lemon, earthenware dish, silver plate, etc. - are compared with each other so as to reveal the characteristics and attractiveness of each. Using a variety of techniques, Heda perfectly conveys the material and the specificity of their texture; Thus, reflections of light play differently on the surface of glass and metal: on glass - light, with sharp outlines, on metal - pale, matte, on a gilded glass - shining, bright. All elements of the composition are united by light and color - a grayish-green color scheme.

In “Still Life with a Candle” by P. Klass, not only the accuracy of the reproduction of the material qualities of objects is remarkable - the composition and lighting give them great emotional expressiveness.

The still lifes of Klass and Kheda are filled with a special mood that brings each other closer together - this is a mood of intimacy and comfort, giving rise to the idea of the well-established and calm life of a burgher's house, where prosperity reigns and where the care of human hands and attentive eyes of the owner is felt in everything. Dutch painters claim aesthetic value things, and the still life, as it were, indirectly glorifies the way of life with which their existence is inextricably linked. Therefore, it can be considered as one of the artistic embodiments important topic Dutch art - themes of the life of a private person. She received her main decision in a genre painting.[&&] Rotenberg I. E. Western European art of the 17th century. Moscow, 1971;

In the second half of the 17th century, changes took place in Dutch society: the bourgeoisie’s desire for aristocracy increased. Klas and Heda's modest "Breakfasts" give way to rich "desserts" Abraham van Beijern And Willem Kalf, which included spectacular earthenware dishes, silver vessels, precious goblets and shells in still lifes. Compositional structures become more complex, and colors become more decorative. Subsequently, still life loses its democracy, intimacy, its spirituality and poetry. It turns into a magnificent decoration for the homes of high-ranking customers. For all their decorativeness and mastery of execution, the late still lifes anticipate the decline of the great Dutch realistic painting, which began at the beginning of the 18th century and was caused by the social degeneration of the Dutch bourgeoisie in the last third of the 17th century, the spread of new trends in art associated with the bourgeoisie’s attraction to the tastes of the French nobility. Dutch art is losing ties with the democratic tradition, losing its realistic basis, losing its national identity and entering a period of long-term decline.

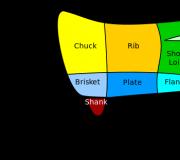

Still life ("Stilleven" - which means "quiet life" in Dutch) - is a unique and quite popular branch of Dutch painting. Dutch still life painting of the 17th century is characterized by the narrow specialization of Dutch masters within the genre. The theme "Flowers and Fruits" usually includes a variety of insects. "Hunting trophies" are, first of all, hunting trophies - killed birds and game. "Breakfasts" and "Desserts", as well as images of fish - alive and asleep, various birds - are only some of the most famous topics still lifes. Taken together, these individual subjects characterize the Dutch’s keen interest in the subjects of everyday life, their favorite activities, and passion for the exoticism of distant lands (the compositions contain outlandish shells and fruits). Often in works with motifs of “living” and “dead” nature there is a symbolic subtext that is easily understandable to an educated viewer of the 17th century.

Thus, the combination of individual objects could serve as a hint of the frailty of earthly existence: fading roses, an incense burner, a candle, a clock; or associated with habits condemned by morality: splinters, smoking pipes; or pointed to love affair; writing, musical instruments, brazier. There is no doubt that the meaning of these compositions is much broader than their symbolic content.

Dutch still lifes attract, first of all, their artistic expressiveness, completeness, and ability to reveal the spiritual life of the objective world. Preferring large-sized paintings with an abundance of all kinds of objects, Dutch painters limit themselves to a few objects of contemplation, striving for the utmost compositional and color unity.

Still life is one of the genres in which Dutch national traits appeared especially clearly. Still lifes depicting humble utensils, so common in Dutch painting and very rare in Flemish painting, or still lifes with household items of the wealthy classes. Still lifes by Pieter Claes and Willem Heda, shrouded in cold diffused light, with an almost monochrome color scheme, or later still lifes by Willem Kalf, where, at the will of the artist, golden lighting brings to life the forms and vibrant colors of objects from the twilight. They all have common national features that will not allow them to be mixed with the paintings of another school, including the related Flemish one. In Dutch still life there is always a feeling of calm contemplation, and a special love for conveying real forms of the tangibly material world.

De Heem gained worldwide recognition for his magnificent images of flowers and fruits. He combined the detail of the image down to the smallest detail with a brilliant choice color range and refined taste in composition. He painted flowers in bouquets and vases, in which butterflies and insects often fluttered, floral wreaths in niches, windows and images of Madonnas in gray tones, garlands of fruit, still lifes with glasses filled with wine, grapes and other fruits and products. Hem masterfully used the possibilities of color and achieved a high degree of transparency; his images of inanimate nature are completely realistic. The canvases of his brush are found in almost all major art galleries. Still life painting, which was distinguished by its character, became widespread in 17th-century Holland. Dutch artists chose a wide variety of objects for their still lifes, knew how to arrange them perfectly, and reveal the characteristics of each object and its inner life, inextricably linked with human life. The 17th century Dutch painters Pieter Claes (c. 1597 - 1661) and Willem Heda (1594 - 1680/1682) painted numerous versions of “breakfasts”, depicting hams, ruddy buns, blackberry pies, fragile glass glasses half filled with wine on the table, with amazing skill conveying the color, volume, texture of each item. The recent presence of a person is noticeable in the disorder, the randomness of the arrangement of things that have just served him. But this disorder is only apparent, since the composition of each still life is strictly thought out and found. A restrained grayish-golden, olive tonal palette unites objects and gives a special sonority to those pure colors that emphasize the freshness of a freshly cut lemon or the soft silk of a blue ribbon. Over time, the “breakfasts” of the still life masters, painters Claes and Heda give way to the “desserts” of the Dutch artists Abraham van Beyeren (1620/1621-1690) and Willem Kalf (1622-1693). Beyeren's still lifes are strict in composition, emotionally rich, and colorful. Throughout his life, Willem Kalf painted in a free manner and democratic “kitchens” - pots, vegetables and aristocratic still lifes in the selection of exquisite precious objects, full of restrained nobility, like silver vessels, cups, shells saturated with the internal combustion of colors. In its further development, still life follows the same path as all Dutch art, losing its democracy, its spirituality and poetry, its charm. Still life turns into decoration for the home of high-ranking customers. For all their decorativeness and skillful execution, the late still lifes anticipate the decline of Dutch painting. Social degeneration and the well-known aristocratization of the Dutch bourgeoisie in the last third of the 17th century gave rise to a tendency towards convergence with the aesthetic views of the French nobility, leading to the idealization of artistic images and their reduction. Art is losing connections with the democratic tradition, losing its realistic basis and entering a period of long-term decline. Severely exhausted in the wars with England, Holland is losing its position as a great trading power and a major artistic center.

Willem Heda (c. 1594 - c. 1682) was one of the first masters of Dutch still life painting in the 17th century, whose work was highly valued by his contemporaries. Particularly popular in Holland was this type of painting called “breakfast”. They were created to suit every taste: from the rich to the more modest. The painting “Breakfast with Crab” is distinguished by its large size, which is uncharacteristic of a Dutch still life (Appendix I). The overall color scheme of the work is cold, silver-gray with a few pinkish and brown spots. Kheda exquisitely depicted a set table on which the items that make up breakfast are arranged in carefully thought out disorder. On the platter lies a crab, depicted with all its peculiarities, next to it is a yellowing lemon, the gracefully cut rind of which, curling, hangs down. On the right are green olives and a delicious bun with a golden crust. Glass and metal vessels add solidity to the still life; their color almost merges with the overall scheme.

An amazing phenomenon in the history of world fine art took place in Northern Europe XVII century. It is known as the Dutch still life and is considered one of the pinnacles of oil painting.

Connoisseurs and professionals have a firm belief that so many magnificent masters, who possessed the highest technology and created so many world-class masterpieces, lived in a small area European continent, has never been seen again in the history of art.

New meaning of the artist's profession

The particular importance that the profession of an artist acquired in Holland from the beginning of the 17th century was the result of the emergence, after the first anti-feudal revolutions, of the beginnings of a new bourgeois system, the formation of a class of urban burghers and wealthy peasants. For painters, these were potential customers who shaped the fashion for works of art, making Dutch still life a sought-after product in the emerging market.

In the northern lands of the Netherlands, reformist movements of Christianity, which arose in the struggle against Catholicism, became the most influential ideology. This circumstance, among others, made the Dutch still life the main genre for entire art guilds. The spiritual leaders of Protestantism, in particular the Calvinists, denied the soul-saving significance of sculpture and painting on religious subjects, they even expelled music from the church, which forced painters to look for new subjects.

In neighboring Flanders, which remained under the influence of Catholics, fine art developed according to different laws, but the territorial proximity determined the inevitable mutual influence. Scientists - art historians - find a lot that unites Dutch and Flemish still life, noting their inherent fundamental differences and unique features.

Early floral still life

The “pure” genre of still life, which appeared in the 17th century, was adopted in Holland special forms And symbolic name“quiet life” - stilleven. In many ways, Dutch still life was a reflection of the vigorous activity of the East India Company, which brought luxury goods from the East that had not been seen in Europe before. From Persia the company brought the first tulips, which later became a symbol of Holland, and it was the flowers depicted in the paintings that became the most popular decoration of residential buildings, numerous offices, shops and banks.

The purpose of masterfully painted floral arrangements was varied. Decorating homes and offices, they emphasized the well-being of their owners, and for sellers of flower seedlings and tulip bulbs, they were what is now called a visual advertising product: posters and booklets. Therefore, the Dutch still life with flowers is, first of all, a botanically accurate depiction of flowers and fruits, at the same time filled with many symbols and allegories. These are the best paintings of entire workshops, headed by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Jacob de Geyn the Younger, Jan Baptist van Fornenburg, Jacob Wouters Vosmar and others.

Set tables and breakfasts

Painting in Holland in the 17th century could not escape the influence of new social relations and economic development. Dutch still life painting of the 17th century was a profitable commodity, and large workshops were organized to “produce” paintings. In addition to the painters, among whom strict specialization and division of labor appeared, those who prepared the base for the paintings - boards or canvas, primed them, made frames, etc. worked there. Fierce competition, as in any market relations, led to an increase in the quality of still lifes to very high level.

The genre specialization of artists also took on a geographical character. Flower arrangements were painted in many Dutch cities - Utrecht, Delft, The Hague, but it was Haarlem that became the center for the development of still lifes depicting set tables, food and ready-made dishes. Such paintings can be varied in scale and character, from complex and multi-subject to laconic. “Breakfasts” appeared - still lifes by Dutch artists depicting different stages of a meal. They depict the presence of a person in the form of crumbs, bitten buns, etc. They told interesting stories, filled with allusions and moralizing symbols common to paintings of that time. The paintings of Nicholas Gillies, Floris Gerrits van Schoten, Clara Peters, Hans Van Essen, Roelof Coots and others are considered particularly significant.

Tonal still life. Pieter Claes and Willem Claes Heda

For contemporaries, the symbols that filled the traditional Dutch still life were relevant and understandable. The contents of the paintings were similar to multi-page books and were especially valued for this. But there is a concept that is no less impressive to both modern connoisseurs and art lovers. It is called "tonal still life", and the main thing in it is the highest technical skill, amazingly refined coloring, amazing skill in rendering subtle nuances lighting.

These qualities are fully consistent with the paintings of two leading masters, whose paintings are considered among the best examples of tonal still life: Peter Claes and Willem Claes Heed. They chose compositions from a small number of objects, devoid of bright colors and special decorativeness, which did not prevent them from creating things of amazing beauty and expressiveness, the value of which does not decrease over time.

Vanity

The theme of the frailty of life, the equality before death of both the king and the beggar, was very popular in the literature and philosophy of that transitional time. And in painting it found expression in paintings depicting scenes in which the main element was the skull. This genre is called vanitas - from Latin “vanity of vanities”. The popularity of still lifes, similar to philosophical treatises, was facilitated by the development of science and education, the center of which was the university in Leiden, famous throughout Europe.

Vanitas occupies a serious place in the works of many Dutch masters of that time: Jacob de Gein the Younger, David Gein, Harmen Steenwijk and others. The best examples of “vanitas” are not simple horror stories, they do not evoke unconscious horror, but calm and wise contemplation, filled with thoughts about the most important questions of life.

Trick paintings

Paintings are the most popular decoration of the Dutch interior since late Middle Ages, which the growing urban population could afford. To interest buyers, artists resorted to various tricks. If their skill allowed, they created “trompe l’oeil”, or “trompe l’oeil”, from the French trompe-l'oeil - an optical illusion. The point was that a typical Dutch still life - flowers and fruits, dead birds and fish, or objects related to science - books, optical instruments, etc. - contained a complete illusion of reality: a book that has moved out of the space of the picture and is about to fall, a fly that has landed on a vase that you want to slam - typical subjects for a decoy painting.

Paintings by leading masters of still life in the trompe l'oeil style - Gerard Dou, Samuel van Hoogstraten and others - often depict a niche recessed into the wall with shelves on which there is a mass of various things. The artist's technical skill in conveying textures and surfaces, light and shadow was so great that the hand itself reached for a book or glass.

Heyday and sunset time

By the middle of the 17th century, the main types of still life in the paintings of Dutch masters reached their peak. “Luxurious” still life is becoming popular, because the welfare of the burghers is growing and rich dishes, precious fabrics and food abundance do not look alien in the interior of a city house or a rich rural estate.

The paintings increase in size, they amaze with the number of different textures. At the same time, the authors are looking for ways to increase entertainment for the viewer. To achieve this, the traditional Dutch still life - with fruits and flowers, hunting trophies and dishes of various materials - is complemented by exotic insects or small animals and birds. In addition to creating the usual allegorical associations, the artist often introduced them simply for positive emotions, to increase the commercial attractiveness of the plot.

The masters of “luxurious still life” - Jan van Huysum, Jan Davids de Heem, Francois Reichals, Willem Kalf - became the harbingers of the coming time, when increased decorativeness and the creation of an impressive impression became important.

End of the golden age

Priorities and fashion changed, the influence of religious dogmas on the choice of subjects for painters gradually became a thing of the past, and the very concept of the golden age that Dutch painting knew became a thing of the past. Still lifes entered the history of this era as one of the most important and impressive pages.