Lamentation of Christ by Giotto. Frescoes by Giotto

Tour to Italy gives unique opportunity get acquainted with the work of the forerunner of Renaissance art - Giotto di Bondone. He was the first artist in the history of Italian (and all Western European) painting to break away from tradition. medieval art, and introduced elements of realism into his works. His biblical scenes feature real people experiencing real human emotions. WITH modern point From a perspective, his painting may seem somewhat simplified. It is indeed far from complete realism. But, any phenomenon of art should be considered in the context historical development. For his time, Giotto was a great innovator. Before him, flatness reigned in painting; the space of paintings became voluminous. Before him, the characters portrayed were emblematic; from him they acquired individual characteristics. Previously, painting was strictly functional (and therefore ritual). The artist’s paintings were filled with various emotions. He was the first to depict clothing realistically, using folds as a hint of a three-dimensional form hidden under the fabric. At the same time, part of the Byzantine canons was preserved. Thus, the characters of saints (as was customary in icon painting) are equipped with halos, indicating their chosenness. Giotto's realism was based on the internal motivation of behavior and the external manifestation of the emotions that gripped a person. It focuses the viewer's attention on meaningful gestures and poses, outlining the figures with a thick, expressive outline. The coloring of the artist’s paintings is strict and consistent. The colors are applied widely and freely, thereby enhancing the linear rhythm and dynamics.

Giotto's naturalistic style was unprecedented news of its time.

It was she who managed to exert a decisive influence on further development Italian painting, giving it expressiveness, depth and expression. Many Renaissance figures paid tribute to Giotto. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, wrote that “Giotto surpassed not only all the masters of his time, but also many artists of previous centuries...”. The Florentine artist Cennino Cennini figuratively described Giotto’s achievements, noting at the turn of the 14th - 15th centuries that he “translated the art of painting from Greek to Latin, making it modern.” By “Greek” Cennini meant formal Byzantine canons, which were generally accepted artistic axioms in medieval Europe. Art Byzantine Empire, who completed her thousand-year existence in 1453, was deeply religious in spirit and strictly conservative in form. IN Byzantine painting there was a limited set of subjects, and the image itself was characterized by conceptual flatness.

Giotto was not the first Italian artist who decided to violate Byzantine regulations.

A little earlier, similar attempts were made by Cimabue (1240 - 1302) and Pietro Cavallini (between 1240 and 1250 - ca. 1330). Both artists strove for the volume of the image and its greater expressiveness. However, Giotto went even further. Human figures in the artist’s paintings they became earthly, their poses and gestures became a mirror of emotions, and the space gained perspective. Thus, the foundations of modern painting were laid, which over the next centuries developed the principles that Giotto formulated with all his creativity.

Giotto's frescoes in the Arena Chapel tell a series of events related to the life of the Virgin Mary, her parents Saint Joachim and Saint Anne, and her son, Jesus Christ. Scenes depicted in the frescoes Sacred History differ in emotional intensity and intensity of passions, but each of them demonstrates the artist’s deep understanding of the plot chosen for a particular work. Any figure in the cycle has not only a voluminous and individual physical form, but also a pronounced moral character. In Giotto's time, fresco was a new genre of painting, and the artist himself became one of the first great masters of this genre. This circumstance largely determined the role of Giotto as the founder new painting in Italy, since for several centuries it was the fresco (with the exception of Venice with its damp climate) that was considered a kind of indicator showing the degree of the artist’s talent, the sharpness of his eye and the firmness of his hand, since there is no possibility of correction during work possible mistakes(the fresco involves applying paints diluted in water onto wet plaster).

Brief description of Giotto's works

Meeting at the Golden Gate. 198 x 183cm. 1303 - 1306 Giotto. Chapel del Arena, Padua.

The location of the frescoes painted by Giotto in the Arena Chapel does not contradict medieval tradition temple decorations, but the artist reinterpreted the gospel story in a new way, presenting it in the form of a consistent story about the life of the family. The story begins with the story of Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin Mary. Noakim and Anna were pious people, but their marriage for a long time remained childless. According to the canons of Judaism, the absence of children was a sign of God's disapproval of marriage. In the end, Joachim had to leave Jerusalem. When Anna reached mature age, an angel who appeared to her said that she would become pregnant and give birth to a child, whose name would become famous in the Universe. With the same news, the heavenly messenger visited Joachim, who was living in exile. After this, Joachim hurried to Jerusalem. The moment of his meeting with his wife (this meeting took place at the Golden Gate leading into the city) was captured by Giotto in his fresco.

Giotto's Flight into Egypt tells of an event dating back to Christ's early childhood.

Shortly after Jesus was born, an angel told his father, Joseph, in a dream that the family must flee to Egypt. Herod, the king of the Jews, who was told that a boy had been born in Bethlehem destined to become the king of the Jews, ordered the extermination of all babies under the age of two born in this city and its environs. The Gospel stories of the “Flight into Egypt” and the “Massacre of the Innocents” were widespread in European church painting. For Giotto, flight is not like flight to direct meaning words; before us is a majestic procession, sedately and leisurely moving through the rocky desert. Giotto could paint animals as skillfully as people, as evidenced by the donkey depicted in the fresco. The composition of the artist’s painting has a pyramidal shape, the base of which is a donkey and at the top are the figures of the Virgin Mary and the Baby Jesus, as if inscribed in the outline of a rocky hill.

The Madonna in Glory is the only surviving altarpiece created by Giotto. The painting takes its name from the Church of Ognissanti (All Saints) in Florence.

The first mention of this work dates back to 1418. The document states that this work was carried out by Giotto. The painting remained in the Ognissanti Church until 1810, after which it was moved to the Accademia Gallery. A little over a century later, in 1919, it was moved to the Uffizi Gallery, where it is still kept, sharing a room, in particular, with the equally famous “Madonna of the Holy Trinity” (c. 1280) by Cimabue. The majestic image of Cimabue is painted primarily in the Byzantine style, with flat, ascetic figures of saints, devoid of any emotion and looking almost incorporeal. Giotto's heroes are voluminous, full of life, which, at the same time, does not detract from their divine greatness. While preserving the traditional composition, the artist achieved great convincing spatial construction. Mary is dressed in simple clothes, having little in common with the precious clothes of the saints depicted on Byzantine icons. Thanks to this, her image looks more earthly.

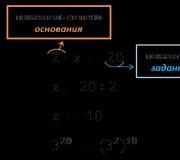

» Lamentation of Christ. 1303-1306 183×183 cm. Giotto. Chapel del Arena, Padua.

The Lamentation of Christ is one of Giotto's most famous works in the Arena Chapel.

The center of the composition is two close faces: dead christ and His Mother. It is here that the rocky slope and the views of the other participants in the scene lead the viewer. The pose of the Mother of God, bending over Christ and incessantly peering into the lifeless face of the Son, is very expressive. The emotional tension of the presented pictorial story is unprecedented; it has no analogues in the painting of this time. The landscape looks symbolic. A rock slope divides the painting diagonally, symbolizing the depth of loss. The poses and gestures of the figures surrounding the body of Christ emphasize emotional condition. The paintings depict Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea experiencing grief, Mary Magdalene, several women in despair, and angels mourning the death of the Savior.

"The Last Supper". The subject became an important theme for the fresco in the Arena Chapel in Padua.

Turning to the heroes gospel story, Giotto endowed them with individual human traits. In the presented image, each character is individual in portraiture. With rare skill, the work conveys the atmosphere of the surrounding space, the calm and majestic composition of which is in perfect harmony with the events described, forming a single ensemble with the interior of the chapel.

"Marriage at Cana" Cappella del Arena in Padua.

The plot tells how Christ at the wedding feast, when there was a shortage of wine, turned water into wine. However, there is not much sense of miracle in this work by Giotto (with the exception of the halos above the heads of the saints). Otherwise, the artist’s desire to depict life’s realities is obvious. The innovation of Giotto's painting style is easy to see by comparing this work with any icon made in traditional style.

The last surviving paintings by Giotto are the frescoes in the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels in the Florentine church of Santa Croce.

"Trial by Fire" is one of them. It is part of a cycle consisting of seven frescoes in the Bardi Chapel, dedicated to life Saint Francis of Assisi. One of the legends tells how, during his wanderings, Saint Francis ended up with the Egyptian Sultan, whom he tried to convert from Islam to Christianity. Wanting to prove the strength of his faith and the power of the true God, he said that he would walk through the fire if the Sultan’s imams did the same after him. The imams refused to repeat the feat of Saint Francis, but the Sultan himself, although he was deeply shocked by what happened, never became a Christian.

With the advent of Giotto, the image and interpretation of the landscape in European art changed beyond recognition. The artist created an image of the world that is adequate to the real world in terms of materiality and spatial depth. Using a number of techniques known at the time, incl. angular angles and simplified (antique) perspective, he managed to give the space the illusion of depth and clarity of composition. At the same time, he developed techniques for tonal light and shadow modeling of forms using gradual lightening of the main, rich colorful tone, which made it possible to give the forms an almost sculptural three-dimensionality, while maintaining, at the same time, the purity of color. The artist depicted scenes from the Gospel with unprecedented convincingness for his time, turning them into fictional story full of drama. Giotto did not lack funds, he loved good joke, and represented the type of man of the new time, who soon began to be called Renaissance. For contemporaries, his works became a rare revelation. “Before the images of Giotto you experience delight, reaching the point of stupor,” wrote Petrarch.

Surely you have heard that Giotto (1266-1337) is considered the father. This is true. And even more. Modern history begins with Giotto European painting. There were icons before him. After him, a completely new art. Which lasted until the end of the 19th century.

You may have seen his murals before. To modern man It's hard to understand what's unusual about them. But when you see the works of his predecessors and contemporaries, you are amazed. How did he manage to create this? Just a clean slate! From scratch.

At the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries it was like a miracle. Crowds of people began to come to the Scrovegni Chapel, which was painted by Giotto. They couldn't believe their eyes. They saw something completely new.

Let's try to look at Giotto's works through the eyes of his contemporaries. To feel all its revolutionary nature.

Before Giotto

Giotto lived and worked in Italy. The country was under strong influence of Byzantium. And Byzantine painting is icons. With strict canons. They very well echoed the worldview of medieval man. The main thing is spiritual qualities. Ascetic lifestyle. Fighting earthly temptations.

All this was manifested in painting. Look at the 13th century fresco.  Unknown Italian master. Donations of Constantine. 13th century Fresco in the monastery of Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome

Unknown Italian master. Donations of Constantine. 13th century Fresco in the monastery of Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome

Flat, symbolic faces. That is, faces. The figures are static, identical. The folds of clothing are unnatural. A horse and rider are suspended in the air. Architecture is toy. After all, the spiritual for a medieval person is more important than the physical. This means that there is no point for the master to achieve the realism of the physical world.

Giotto's innovation

The easiest way to understand Giotto's innovation is through his main masterpiece. Cycle of frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

These are stories from the lives of Mary and Jesus Christ. Size 2.5 by 2 m. 39 images.

Let's take a look at just a few of them. This is enough to understand the genius of Giotto.

1. Annunciation to St. Anne

Giotto. Annunciation to Saint Anne. 1303-1305 Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Annunciation to Saint Anne. 1303-1305 Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy In the fresco “Annunciation to St. Anne,” the heroine receives good news from an angel. An elderly woman will be able to conceive and give birth to a girl. Future Saint Mary.

For the first time, people of the Middle Ages saw an aging face. The present. Before this, saints over 50 were depicted schematically, without any special signs of old age. Giotto thereby approaches the truthfulness of life. Moving away from iconographic symbolism.

Right: unknown Serbian master. Icon “St. Anna with the Child Mary.” 14th century Zagorsk Museum-Reserve, Sergiev Posad, Russia

Giotto was the first to overcome the flatness of figures. He gives his characters volume and weight. Something you won't see from his predecessors.

Look at the figure of the maid spinning under the stairs. This is already an image of a living person. We see its volume. The woman moved one knee to the side. And the folds of clothing echo this movement.

It's extraordinarily realistic. Compare her at least with Saint Mary in the icon of Guido da Siena. How symbolic its folds are. How flat is the figure of the saint? Although these works are separated from each other by only a couple of decades.

Right: Guido da Siena (Italian master). Adoration of the Magi. 1275-1280 Altenburg, Lindenau Museum, Germany

Another interesting point. The characters are depicted in the interior. We see everyday details of their lives. Shelf, chest, bench. Before Giotto, people were not depicted in the interior. But this makes the image even more realistic.

Giotto. Meeting at the Golden Gate. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Meeting at the Golden Gate. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy The future parents of Saint Mary, Joachim and Anna, met at the Golden Gate. The husband understood without words what his wife wanted to tell him. In a rush tender feelings two no longer young people kiss.

Giotto showed the tender intimate feelings of people very expressively. Before Giotto, you will not find such sincerity of feelings. The hugs of the spouses are so tender. Their kiss is so touching.  Giotto. Meeting at the Golden Gate. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Meeting at the Golden Gate. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Note that Joachim and Anna are not in the center. They are shifted to the left. In the center are women in black and white. Perhaps they are symbolic. Like, next to happiness there is always grief. After all, we all know what a painful loss their daughter Mary will have to endure.

Here we can safely say that Giotto was the first to create the composition. This is exactly how he saw the scene. He invested certain meaning to place secondary figures in the center.

Before Giotto, the concept of composition simply did not exist. And a medieval master would place the spouses exactly in the middle.  Miniature “Meeting at the Golden Gate”. Minology of Vasily II. 10th century Kept in the Vatican Library, Vatican

Miniature “Meeting at the Golden Gate”. Minology of Vasily II. 10th century Kept in the Vatican Library, Vatican

3. Adoration of the Magi

Giotto. Adoration of the Magi. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Adoration of the Magi. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy Giotto departs from the gold background accepted at that time. He paints his frescoes with blue skies. This is already a real three-dimensional space. Not an abstract golden void.

His heroes stand firmly on their feet. Remember how the masters before him neglected this. Horses and people could “hover” above the ground.

Giotto's heroes are also full of inner dignity. These are sincere people. Living people. Unlike the mask faces of Byzantium.

Everyone knows biblical stories the master makes them truthful and vital. It's like this is happening in reality. WITH real people. Giotto. Adoration of the Magi. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Compare the “Adoration of the Magi” by two contemporary masters. And you will understand all the amazement of people who saw Giotto’s works for the first time. After all, the master seemed to explain the otherworldly, transcendental biblical stories in simple, in clear language.

Left: Guido da Siena (Italian master). Adoration of the Magi. 1275-1280 Altenburg, Lindenau Museum, Germany

By the way, the star depicted in the sky is unusual. It is believed that Giotto depicted Halley's Comet, which was visible to the naked eye in 1301.

4. Kiss of Judas

Giotto. Kiss of Judas. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Kiss of Judas. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy The fresco depicts a scene of betrayal. The bribed Judas must give a sign to the guards. So that they understand which of those standing is Jesus. Judas must kiss him.  Giotto. Kiss of Judas. 1303-1305 Detail of a fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Kiss of Judas. 1303-1305 Detail of a fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

In the center we see two faces. Noble, Beautiful face Christ with regular features. High forehead. Developed neck of a healthy man. And the ape-like, ugly face of Judas. Prominent brow ridges. Sloping chin. Small, seemingly shifting eyes.

Moral beauty is combined with physical beauty. And physical deformity is accompanied by moral deformity. This is exactly how it will be done after Giotto during the Renaissance. The beauty of faces noble people and the ugliness of traitors.

Remember how terrible Judas is portrayed in his famous fresco “last supper”.

Works by Leonardo da Vinci from 1498. Left: fragment of a fresco. Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Right: “Head of Judas.” Preparatory drawing to the fresco “The Last Supper”. Windsor Castle, England

Read more about this fresco in the article

5. The Flagellation of Christ

Giotto. The Flagellation of Christ. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. The Flagellation of Christ. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy The volume of the figures is especially noticeable in the fresco “The Flagellation of Christ”. They are heavy. Even blocky. No wonder. Giotto, of course, did not know human anatomy. But he tried his best to show people in volume. Which means real.

This fresco is also remarkable for something else. Look how different Christ's tormentors are. Both in appearance and in facial expressions. Such individuality had never been found among medieval masters before Giotto.  Giotto. The Flagellation of Christ. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. The Flagellation of Christ. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

6. Lamentation of Christ

Giotto. Lamentation of Christ. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Lamentation of Christ. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy Drama. Grief and grief are depicted incredibly believably. These are no longer conventional gestures. And the most real emotions.  Giotto. Lamentation of Christ. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto. Lamentation of Christ. Fragment. 1303-1305 Fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

"Lamentation of Christ"– fresco of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua is one of the main masterpieces of Giotto di Bondone. Having overcome the Byzantine canon, his “Lamentation” opened up many unknown techniques and new possibilities for art. “Pieta” (the Greek word for mourning) will soon become a very popular subject in Italian painting. And this will not happen without the influence of Giotto’s work, which concentrated many innovative discoveries.

What are his artistic discoveries?

Firstly, in storytelling. We see that Giotto does not perceive the “Lamentation of Christ” as a ready-made iconographic formula. On the contrary, he is interested in telling the viewer this story anew - in a way that no one has done before. Giotto is openly passionate about drama. It is important for him to show the emotional meaning of what is happening, how differently the heroes of the gospel events express their sadness. Silent and inescapably deep is the sorrow of the Virgin Mary. Women wring their hands in despair and anguish. Mary Magdalene weeps at the feet of Christ. Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathes endure grief stoically. And the widely spread arms of John the Evangelist, the Savior’s beloved disciple, at the same time remind of the crucifixion and something avian (the eagle symbolizes this apostle in religious literature).

However, Giotto's characters in Lamentation are not emblems or extras. They are all involved in the action in different ways, and their gestures and poses (noted by Giotto quite accurately and conveyed with unprecedented realism for the beginning of the 14th century and at the same time reminiscent of the heroes of Greek tragedy, who, in a fit of passion, raise their hands up or cover their faces ) are added up into a single emotional background. In Byzantine painting, poses and gestures had symbolic meaning, but from now on painting will use them to express feelings. In Giotto, not only people, but even angels lose their iconographic static and begin to demonstrate emotions.

Giotto's second discovery follows from the previous one. It lies in the fact that painting ceases to be a simple illustration biblical text and acquires independent value. The sacred plot becomes interesting to the artist not only in itself, but also from the point of view of revealing new spatial possibilities, unexpected compositional solutions. For example, what happens if you shift the semantic center of the picture away from its geometric center? “Lamentation” successfully solves this creative problem. The semantic center here, of course, is the close faces of Christ and the Virgin Mary, placed in the lower left corner.

In general, two heads located close to each other are Giotto’s favorite technique. The artist knows how to extract psychological and emotional effects from it. Suffice it to recall Iscariot and Christ standing nose to nose in The Betrayal of Judas. But there two faces, concentrating all the viewer’s attention on themselves, are located in the spatial center of the fresco. In “Lamentation,” the semantic center is greatly shifted, deliberately shifted. But look how skillfully Giotto directs the viewer’s gaze to him: it is there that our eyes are directed, sliding down the diagonal of the rock, pushing back the sky in bright contrast. It is there, in the lower left corner, like the radii of an invisible circle, that the views of both the angels soaring in the sky and the people bending around the body of Christ are directed. The composition acquires extraordinary thoughtfulness and harmony.

Of course, in retrospect, after all the Lamentations of the Italians, Spaniards and Dutch, written in the Renaissance and Baroque periods (

Giotto's work marks the formation of that powerful artistic phenomenon that became the art of the Renaissance in Italy. A true reformer of painting, he decisively breaks with medieval traditions.

Paolo Uccello. Portrait of Giotto

(detail of the painting “Five Founders”

Florentine art")

Late XV - early XVI centuries.

Paolo Uccello. Portrait of Giotto

(detail of the painting “Five Founders of Florentine Art”)

Late XV - early XVI centuries.

The most famous work Giotto - a cycle of frescoes depicting episodes from the life of Christ and Mary in the Arena Chapel in Padua (c. 1305). The cycle consists of 36 frescoes depicting the youth of Christ and the Passion. Their placement on the walls is strictly thought out taking into account the layout of the chapel and its natural lighting. Mastering the methods of light and shadow modeling of form, he achieved the image of three-dimensional, weighty figures, full of living feelings and experiences (“Mourning of Christ”).

Giotto di Bondone. Lamentation of Christ

Fresco. OK. 1305

Chapel del Arena, Padua.

Giotto di Bondone. Lamentation of Christ

Fresco. OK. 1305

Chapel del Arena, Padua.

Such an earthly beginning was sharply different from artistic techniques, Giotto's predecessors and his contemporaries, gave special expressiveness and significance to all scenes. The frescoes are located on the wall in a clear order, creating a majestic ensemble. Their compositional rhythm perfectly corresponds to the selected subjects, which are interpreted with epic restraint and solemnity. All characters are endowed with plastic integrity, spirituality, and strength. How dramatic events clashes of different human characters are shown (scene “The Kiss of Judas”).

Giotto di Bondone. Kiss of Judas

Fresco. Between 1304 and 1306

Chapel del Arena, Padua.

Giotto di Bondone. Kiss of Judas

Fresco. Between 1304 and 1306

Chapel del Arena, Padua.

Frescoes painted later in Peruzzi Chapels and Bardi of the Florentine Church of Santa Croce, are also distinguished by the vitality of their images, although there is less expression in them; on the contrary, here Giotto strives for some restraint of feelings, for even greater solemnity and majesty. Beautiful earthly woman depicted by the artist “Madonna” (Uffizi Gallery, Florence).

In the dramatic Lamentation of Christ, against the backdrop of bare rock with a single dead tree, a group of disciples and women surround the dead Christ, prostrate on the ground. Sitting on foreground with their backs to the viewer, figures in wide robes seem to close the mournful scene.

This masterpiece by Giotto is the most stunning of the frescoes of the Chapel del Arena, it showed everything that was innovative in Giotto's work - the emotional tension of a living narrative is unprecedented in the art of Tretecento. It's like we're present real event, unfolding as if on a stage. The center of the composition is two close faces: the dead Christ and His Mother, the diagonal of the rocky slope runs towards them, the views of all the characters in the scene are directed towards them. The pose of the Mother of God, bending over Christ and incessantly peering into the lifeless face of the Son, reaches extreme expressiveness.

The characters surrounding Jesus are filled with sorrow, the whole gamut of feelings and experiences is masterfully conveyed through their gestures and poses. The images of the mourners are given in a generalized manner, excluding the possibility of manifestation individual traits human characters.

The sorrowful solemnity of the moment is set off by the draped figures in the foreground, reminiscent of sculptures of grief. The figures surrounding the body of Christ express various emotions with their restrained, mournful poses and gestures: Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea stoically experience grief, Mary Magdalene, sobbing, bent over the pierced feet of Christ, St. John, in a passionate outburst, leaned forward, with his arms outstretched, peering into the beloved face of the Teacher. . His figure is a closed plastic volume. The head and hands of the saint seem to be opposed to the single volume of the body. The falling folds of the cloak only emphasize, but do not repeat, the gesture of despair of the arms spread wide and pulled back, and the mood of sorrow and humility finds its highest expression in the face directed towards Christ, in the intense gaze of the saint. Women wringing their hands in despair, and angels mourning the death of the Savior - their flight, turning into a fall, emphasizes the universal significance of the ongoing tragedy. In the tragic scene captured by Giotto, each character expresses his grief with such conviction that it can be discerned even in the sorrowful poses of the sitting figures, whose faces we do not see.

The depth of space is created by placing the symbolic composition in perspective mountain landscape. A stone slope divides the picture diagonally, emphasizing the depth of the fatal loss. The entire composition, even the sense of depth, is created by human figures.

M. Alpatov about Giotto's fresco of the Arena Chapel in Padua, Lamentation of Christ

“After this, Joseph from Arimathea, a disciple of Jesus, but secretly out of fear from the Jews, asked Pilate to remove the body of Jesus; and Pilate allowed it. He went and took down the body of Jesus.

Nicodemus, who had previously come to Jesus at night, also came and brought a composition of myrrh and aloes, about a hundred liters.

So they took the body of Jesus and wrapped it in swaddling clothes with spices, as the Jews are wont to bury.

In the place where He was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden there was a new tomb, in which no one had yet been laid.

They laid Jesus there for the sake of the Friday of Judea, because the tomb was near.”

Gospel of John 19:38-42.