Man and the totalitarian state in the works of Solzhenitsyn. Essay “Man in a totalitarian state (based on the story by A. I. Solzhenitsyn “Matrenin’s Dvor”)

Works of literature about the fate of man in a totalitarian society (list): E. Zamyatin “We”, A. Platonov “The Pit”, “Chevengur”, A. Solzhenitsyn “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, “The Gulag Archipelago”, “In the First Circle” , “Cancer Ward”, V. Shalamov “ Kolyma stories”, V. Grossman “Life and Fate”, A. Rybakov “Children of the Arbat”, etc., G. Vladimov “Faithful Ruslan”, Y. Daniel “Redemption”

The theme of man and the totalitarian state in literature

Understanding the theme of man in a totalitarian society began in the 20s with the advent of the dystopian genre - the novel “We” by E. Zamyatin. Zamyatin's novel, written during the years of war communism, became a warning to humanity. A person in a totalitarian society is deprived of a name, and therefore of individuality, he is designated by a letter and numbers. All its activities are regulated by the state, up to sexual relations. In order to check the correctness of the flow of life, a whole army of observers is needed. The life of the hero and his fellow citizens is imbued with faith in the Benefactor, who knows better than others how to make life beautiful. The election of the Benefactor turns into a national holiday.

An integral feature of a totalitarian society is the conviction of a person that what the state gives him is good, that there is no better country in the world.

A totalitarian state needs scientists who would help strengthen its power, but it does not need people with imagination, because fantasy makes a person think, see what the state would prefer to hide from its citizen. It is love that makes the hero rebel, but his rebellion is broken: he passively watches the murder of his beloved, he, devoid of imagination. It is love that becomes the enemy of totalitarianism, because it makes a person an individual, makes him forget the image of the Benefactor. O-90's maternal love forces her to protest, to flee the state in order to save the child, and not give him to the state. The novel “We” has universal significance; it is a reflection of any totalitarian regime based on the suppression of the human personality.

Solzhenitsyn's novels

The works of A. Solzhenitsyn are based on material experienced by the author himself. The writer is an ardent opponent of Soviet power as a totalitarian power. He tries to show the characters of people whose destinies are broken by society. This is the situation in the novel “Cancer Ward” - a model different representatives Soviet world, gathered in the hospital by one misfortune - illness (cancer). Each image is a strong belief system: Oleg Kostoglotov, ex-convict, an ardent opponent of the system, understanding all its anti-humanism; Shulubin, a Russian intellectual, participant in the revolution, outwardly accepts official morality, suffering from its inconsistencies; Rusanov is a man of the nomenklatura, for whom everything prescribed by the party and the state is accepted unconditionally; he does not torment himself with moral questions, but sometimes benefits from his position. Main question disputes over whether the existing system is moral. According to the author and his hero, Oleg, the answer is clear: the system is immoral, it poisons the souls of children even at school, teaching them to be like everyone else, depriving them of their personality; it reduces literature to serving its own interests (to recreate the image of a beautiful tomorrow), this is a system with a shifted scale of values that demands the same from a person. The fate of a person depends on the choice he makes.

A. Solzhenitsyn will write about this somewhat differently in “Archipelago”: he will say that in a totalitarian society, his insight depends on the fate of a person (the reasoning is that he could turn out not to be a prisoner, but an NKVD officer).

Works by G. Vladimirov

The totalitarian system distorts the best traits of human character and leaves a mark for life. “Faithful Ruslan” is the story of a camp dog.

G. Vladimov shows that even after the dissolution of the camps, the camp dogs continue to wait for their duty to be fulfilled - they can’t do anything else. And when young builders arrive at the station and march in a column to the construction site, dogs surround them, which at first seems funny to the young people, and then terrible. A totalitarian system teaches a person to love his master and obey him unquestioningly. But there is a scene in the novel that shows that submission is not limitless: the prisoners refuse to leave the barracks in the cold, then the head of the camp orders to open the doors and pour ice water on the inside of the barracks, and then one of the shepherd dogs, the most talented one, clamps the hose with her teeth: so the beast protests against the inhumanity of people. The dying Ruslan dreams of his mother, the one whom the state took away from him, depriving him of his true feelings. And if Ruslan himself evokes sympathy, then the image of his master is disgusting in its primitiveness, cruelty, and soullessness.

Y. Daniel and the novel about the Thaw

The horror of totalitarianism is that even the souls of people with a fairly prosperous fate are broken by the totalitarian regime. The action of Y. Daniel's story "Atonement" takes place during the period Khrushchev's thaw. Main character story - he is talented, honest, happy, he has many friends, a wonderful woman loves him. But then an accusation falls upon him: a fleeting old acquaintance of the hero returns from the camp: he is convinced that he was imprisoned as a result of the hero’s denunciation. But the writer initially claims that the hero is not guilty. And now, without trial or investigation, without explanation, the hero finds himself in isolation: not only his colleagues, but also his friends have turned their backs on him; his beloved, unable to bear it, leaves. People are used to accusations, they believe everything; it doesn’t matter that in this case the poles change (the enemy of the people is an informer). The hero goes crazy, but before that he understands that everyone in this society is guilty, even those who have lived a quiet life. Everyone is poisoned by the poison of totalitarianism. To get rid of it, like to get rid of oneself as a slave, is the process of life of more than one generation.

The fate of a person in a totalitarian society is tragic - this is the conclusion of all works on this topic, but the attitude towards certain people varies domestic writers different, as different and from position.

Did you like it? Don't hide your joy from the world - share itMaterials are published with the personal permission of the author - Ph.D. Maznevoy O.A.

Subject tragic fate person in totalitarian state(using the example of A.I. Solzhenitsyn’s story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”)

In his famous story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn described only one day of a prisoner - from wake-up until bedtime, but the narrative is structured in such a way that the reader can imagine the camp life of the forty-year-old peasant Shukhov and his entourage in its entirety. By the time the story was written, its author was already very far from socialist ideals. This story is about the illegality, the unnaturalness of the very system created by the Soviet leaders.

The image of the main character is collective. Shukhov's main prototype is often cited as Ivan, a former soldier from Solzhenitsyn's artillery battery. Moreover, the writer himself was a prisoner who, every day of his stay in the camp, observed thousands of broken human destinies and tragedies. The material for his story was the result of terrible lawlessness, which had nothing to do with justice. Solzhenitsyn is sure that the Soviet camps were the same death camps as the fascist ones, only they killed their own people there.

Ivan Denisovich realized long ago that to survive it was not enough to feel like a Soviet person. He got rid of ideological illusions that were useless in the camp. This inner conviction of his is clearly demonstrated by the scene when captain Buynovsky explains to the hero why the sun is at its zenith at one o'clock in the afternoon, and not at 12 o'clock. By government decree, the time in the country was moved forward an hour. Shukhov is surprised: “Does the sun really obey their decrees?” Shukhov now has a different relationship with the Soviet government. He is the bearer of universal human values, which party-class ideology failed to destroy in him. In the camp, this helps him to survive, to remain human.

The fate of prisoner Shch-854 is similar to thousands of others. He lived honestly, went to the front, but was captured. He managed to escape from captivity and miraculously made his way to “his own people.” This was enough for a serious charge. “Counterintelligence beat Shukhov a lot. And Shukhov’s calculation was simple: if you don’t sign, it’s a wooden pea coat; if you sign, you’ll at least live a little. Signed."

Whatever Shukhov does, he pursues one goal every day - to survive. Prisoner Shch-854 tries to watch his every step, earn extra money whenever possible and lead a tolerable existence. He knows that the usual practice for a charge as serious as his is to add prison time. Therefore, Shukhov is not sure that he will be free at the appointed time, but he forbids himself to doubt. Shukhov is serving imprisonment for treason. The documents that he was forced to sign indicate that Shukhov carried out tasks for the Nazis. Neither the investigator nor the person under investigation could come up with which ones exactly. Shukhov doesn’t think about why he and many other people are in prison, he’s not tormented eternal questions no answers.

By nature, Ivan Denisovich belongs to natural, natural people who value the process of life itself. And the prisoner has his own little joys: drink hot gruel, smoke a cigarette, calmly, with pleasure, eat a ration of bread, hide somewhere warmer, and take a nap for a minute until they go to work. Having received new boots, and later felt boots, Shukhov rejoices like a child: “...life, no need to die.” He had a lot of successes during the day: “he wasn’t put in a punishment cell, the brigade wasn’t sent out to Sotsgorodok, he made porridge at lunchtime, he didn’t get caught with a hacksaw on a patrol, he worked at Caesar’s in the evening and bought some tobacco. And I didn’t get sick, I got over it.”

In the camp Shukhov’s work saves him. He works enthusiastically, regrets when his shift ends, and hides a trowel convenient for a mason for tomorrow. He makes decisions from a position of common sense, based on peasant values. Work and attitude to work do not allow Ivan Denisovich to lose himself. He does not understand how one can treat work in bad faith. Ivan Denisovich “knows how to live,” think practically, and not throw words to the wind.

In a conversation with Alyoshka the Baptist, Shukhov expresses his attitude towards faith and God, again guided by common sense. “I’m not against God, you know,” explains Shukhov. – I willingly believe in God. But I don’t believe in hell and heaven. Why do you consider us fools and promise us heaven and hell?” When asked why he doesn’t pray to God, Shukhov replies: “Because, Alyoshka, those prayers are like statements, either they don’t reach, or the complaint is refused.” This is hell, the camp. How did God allow this to happen?

Among Solzhenitsyn’s heroes there are also those who, despite performing a small feat of survival every day, do not lose their dignity. Old man Yu-81 is in prisons and camps, how much does Soviet power cost? Another old man, X-123, is a fierce champion of truth, deaf Senka Klevshin, a prisoner of Buchenwald. Survived torture by the Germans, now in a Soviet camp. Latvian Jan Kildigs, who has not yet lost the ability to joke. Alyoshka is a Baptist who firmly believes that God will remove the “evil scum” from people.

Captain of the second rank Buinovsky is always ready to stand up for people, he has not forgotten the laws of honor. To Shukhov, with his peasant psychology, Buinovsky’s behavior seems a senseless risk. The captain was sharply indignant when the guards, in the cold, ordered the prisoners to unbutton their clothes in order to “feel to see if anything had been put on in violation of the regulations.” For this Buinovsky received “ten days of strict imprisonment.” Everyone knows that after the punishment cell he will lose his health forever, but the conclusion of the prisoners is this: “There was no need to get screwed! Everything would have worked out.”

The story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” was published during the “Khrushchev Thaw” in 1962, caused a great resonance among readers, and opened the world the terrible truth about the totalitarian regime in Russia. Solzhenitsyn shows how patience and life ideals help Ivan Denisovich survive in the inhuman conditions of the camp day after day.

On the topic: methodological developments, presentations and notes

Reflections on the story by A.I. Solzhenitsyn "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich"

To attract students' interest in the personality and work of A. I. Solzhenitsyn, who became a symbol of openness, will and Russian directness; show “unusual life material”, taken...

Topic: The tragedy of the 30s in the history of Russia and its reflection in the story by A. I. Solzhenitsyn “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

Integrated lesson literature - history...

will save a person in an inhuman life, what is his highest purpose; help to understand what contributes to moral purification....

STATE AUTONOMOUS EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION

SECONDARY VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

NOVOSIBIRSK REGION

"BARABINSKY MEDICAL COLLEGE"

METHODOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

COMBINED LESSON FOR TEACHER

Specialty 060501 Nursing

Discipline "Literature"

Section 2. Literature of the 20th century

Topic 2.23. A.I. Solzhenitsyn. The theme is the tragic fate of man in a totalitarian state. "One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich"

Approved at a meeting of the cyclic methodological commission of general humanitarian and socio-economic disciplines

Protocol No._____ dated ______20_______.

Chairman___________________________

Methodological sheet……………………………………………………..4

Extract from the work program…………………………………….5

Approximate time map of the lesson………………………………………..6

Source material…………………………………………………….7

Appendix No. 1…………………………………………..…………...14

Appendix No. 2……………………………………………………………..………15

Appendix No. 3………………………………………………………..16

METHODOLOGY SHEET

Type of lesson – combined lesson.

Duration – 90 min.

OBJECTIVES OF THE LESSON

Learning objectives:

Develop the ability to analyze and interpret piece of art, using information on the history and theory of literature (topics, problems, moral pathos, system of images, features of composition, visual means of expression language, artistic detail); determine the type and genre of the work; basic facts of the life and work of classical writers of the 19th-20th centuries.

2. Developmental goals:

To promote the development of knowledge of the basic facts of the life and work of classical writers of the 19th-20th centuries; understanding the essence and social significance of your future profession, sustainable interest in it;

Develop the ability to analyze life situations, draw conclusions, accept independent decisions, be organized and disciplined; to form practical creative thinking.

3. Educational goals:

Promote development communicative culture, sense of responsibility.

Teaching methods– reproductive.

Location of the lesson- college auditorium.

Relevance of studying the topic. A.I. Solzhenitsyn is a world-famous writer, a person with unusual biography, a bright personality who entered into combat with political system of the entire state and has earned the respect and recognition of the whole world. The genuine interest of readers in the figure and work of Solzhenitsyn determines his place and role in the modern world literary process. Study of life and creativity outstanding writer means becoming familiar with the history of one’s homeland, coming closer to understanding the reasons that led society to a political, economic and moral crisis. In this regard, it is necessary for everyone to expand their knowledge in the field of literature. educated person, including future medical workers.

References

Russian literature of the 20th century, grade 11. Textbook for general education institutions. In 2 parts. Part 2 [Text]/ V.A. Chalmaev, O.N. Mikhailov and others; Comp. E.P. Pronina; Ed. V.P. Zhuravleva. – 5th ed. – M.: Education, 2010. – 384 p.

Solzhenitsyn, A.I. One day of Ivan Denisovich [Text]/ A.I. Solzhenitsyn. – M.: Education, 2013. – 96 p.

Extract from the thematic plan of the discipline “Literature”

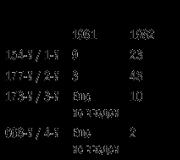

| Topic 2.23. A.I. Solzhenitsyn. The theme is the tragic fate of man in a totalitarian state. "One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich" | ||

| Basic facts of the writer’s life and work. "One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich." The tragic fate of a person in a totalitarian state. Organic unity of artistic and journalistic. Problems of tradition with innovation. Publicism of a work of art. | ||

| Independent work of students: Working with the textbook; Working with lecture notes (reasonably formulate your attitude to the work you read); Reading and analysis of a work (knowledge and reproduction of the content of a literary work). |

SAMPLE CHRONOCARD OF A CLASS

| Stage name | Time | Purpose of the stage | Activity | Equipment |

|||

| teacher | students |

||||||

| Organizational stage | Organizing the start of classes, preparing the students’ workplace | Marks absent students in the log | The headman calls the absent students. Students adjust their appearance and prepare their workplaces. | Magazine, notebooks |

|||

| Poetic moment | Repetition of the work of Russian poets | Listens to poems performed by students, evaluates the expressiveness of reading | Reading poetry | Group Grading Journal, Appendix 3 |

|||

| Motivational stage | Developing interest in a new topic | Explains to students the importance of studying this topic | Listen, ask questions |

|

|||

| Lesson objectives | Setting priorities when studying a topic | Voices the objectives of the lesson | Listen, write down a new topic in a notebook | Methodological development classes |

|||

| Testing knowledge on the previous topic | Determining the degree to which students are prepared for the lesson and the degree to which they have mastered the material on the previous topic |

| Answer questions about the topic covered, retell | Annex 1. |

|||

| Presentation of background information | To promote the development of knowledge of the basic facts of the life and work of classical writers of the 19th-20th centuries; understanding the essence and social significance of your future profession, sustainable interest in it | Sets forth new material | Listen, read the material in the textbook, write down | Methodological development of the lesson (source material) |

|||

| Completing tasks to consolidate knowledge | Consolidation of knowledge, reading text, work in subgroups | Instructs and controls the completion of tasks, discusses the correctness of answers | Complete assignments, work in subgroups on prepared questions | Appendix 2 |

|||

| Preliminary control of new knowledge | Assessing the effectiveness of the lesson and identifying deficiencies in new knowledge, text analysis | Instructs and supervises | Present completed tasks, read out the text in compliance with the basic rules, listen to other answers, make adjustments | Appendix 2 |

|||

| Assignment for independent extracurricular work of students | Formation and consolidation of knowledge | Gives assignments for independent extracurricular work of students, instructs them on the correct execution | Write down the task | - Re-work on educational material(lecture notes); - work according to the textbook; - reading and analysis of the work |

|||

| Summarizing | Systematization, consolidation of material, development of emotional stability, objectivity in assessing one’s actions, ability to work in a group | Evaluates the work of the group as a whole, individually, motivation for evaluation | Listen, ask questions, participate in discussion | Group Journal |

|||

RAW MATERIAL

Childhood and youth

Alexander Isaevich (Isaakievich) Solzhenitsyn born December 11, 1918 in Kislovodsk.

Father - Isaac Semyonovich Solzhenitsyn, a Russian Orthodox peasant from the North Caucasus. Mother - Ukrainian Taisiya Zakharovna Shcherbak, daughter of the owner of the richest house in Kuban savings, who with his intelligence and labor rose to this level of a Tauride shepherd-farmer. Solzhenitsyn's parents met while studying in Moscow and soon got married. During the First World War, Isaac Solzhenitsyn volunteered to go to the front and served as an officer. He died before the birth of his son, on June 15, 1918, after demobilization (as a result of a hunting accident). He is depicted under the name Sanya Lazhenitsyn in the epic “The Red Wheel” (based on his wife’s memories).

As a result of the revolution and civil war the family was ruined, and in 1924 Solzhenitsyn moved with his mother to Rostov-on-Don, from 1926 to 1936 he studied at school, living in poverty.

In elementary school, he was ridiculed for wearing a baptismal cross and unwillingness to join the pioneers, and was reprimanded for attending church. Under the influence of school, he accepted communist ideology and joined the Komsomol in 1936. In high school, I became interested in literature and began writing essays and poems; interested in history social life. In 1937 he conceived a “great novel about the revolution” of 1917.

In 1936 he entered the Rostov State University. Not wanting to make literature my main specialty, I chose the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics. According to the recollection of a school and university friend, “... I studied mathematics not so much by vocation, but because in physics and mathematics there were exceptionally educated and very interesting teachers" One of them was D. D. Mordukhai-Boltovskoy (under the name Goryainov-Shakhovsky, Solzhenitsyn would feature him in the novel “In the First Circle” and in the poem “Dorozhenka”). At the university, Solzhenitsyn studied with excellent marks (Stalin's scholarship recipient), continued literary exercises, and, in addition to university studies, independently studied history and Marxism-Leninism. He graduated from the university in 1941 with honors, he was awarded the qualification researcher II category in the field of mathematics and teacher. The dean's office recommended him for the position of university assistant or graduate student.

From the very beginning of his literary activity, he was keenly interested in the history of the First World War and the Revolution. In 1937, he began collecting materials on the “Samson Disaster” and wrote the first chapters of “August the Fourteenth” (from an orthodox communist position). In 1939 he entered the correspondence department of the Faculty of Literature of the Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History in Moscow. He interrupted his studies in 1941 due to the war.

He was interested in theater, in the summer of 1938 he tried to pass exams at drama school Yuri Zavadsky, but unsuccessfully.

In August 1939, he and his friends took a kayak trip along the Volga. The life of the writer from this time until April 1945 is in the poem “Dorozhenka” (1948-1952).

On April 27, 1940, he married Natalya Reshetovskaya (1918-2003), a student at Rostov University, whom he met in 1936.

During the war

With the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Solzhenitsyn was not immediately mobilized, since he was considered “limitedly fit” for health reasons. He actively sought a call to the front. In September 1941, together with his wife, he was assigned as a school teacher in Morozovsk, Rostov region, but on October 18 he was drafted and sent to a horse-drawn cargo train as a private.

The events of the summer of 1941 - spring of 1942 are described by Solzhenitsyn in his unfinished story “Love the Revolution” (1948).

He sought assignment to an officer's school, and in April 1942 he was sent to an artillery school in Kostroma; in November 1942, he was released as a lieutenant and sent to Saransk, where a reserve regiment was located to form artillery instrumental reconnaissance divisions.

In the active army since February 1943, he served as commander of a sound reconnaissance battery. He was awarded the Order of the Patriotic War and the Red Star, in November 1943 he received the rank of senior lieutenant, and in June 1944 - captain.

At the front, he kept war diaries, wrote a lot, sent his works to Moscow writers for review; in 1944 received a favorable review from B. A. Lavrenev.

Arrest and imprisonment

At the front, Solzhenitsyn continued to be interested in public life, but became critical of Stalin (for “distorting Leninism”); in correspondence with an old friend (Nikolai Vitkevich), he spoke abusively about “Godfather,” by whom Stalin was guessed, kept in his personal belongings a “resolution” drawn up together with Vitkevich, in which he compared the Stalinist order with serfdom and spoke about the creation of an “organization” after the war to restore the so-called “Leninist” norms. The letters aroused suspicion of military censorship, and in February 1945 Solzhenitsyn and Vitkevich were arrested.

After his arrest, Solzhenitsyn was taken to Moscow; On July 27, he was sentenced in absentia by a Special Meeting to 8 years in forced labor camps.

Conclusion

In August he was sent to a camp in New Jerusalem, on September 9, 1945 he was transferred to a camp in Moscow, whose prisoners were engaged in the construction of residential buildings on the Kaluga Outpost (now Gagarin Square).

In June 1946, he was transferred to the special prison system of the 4th Special Department of the NKVD, in September he was sent to a special institute for prisoners (“sharashka”) at the aircraft engine plant in Rybinsk, five months later - to a “sharashka” in Zagorsk, in July 1947 - to a similar establishment in Marfino (near Moscow). There he worked as a mathematician.

In Marfin, Solzhenitsyn began work on the story “Love the Revolution.” Later, the last days at the Marfinskaya sharashka were described by Solzhenitsyn in the novel “In the First Circle,” where he himself was introduced under the name of Gleb Nerzhin, and his cellmates Dmitry Panin and Lev Kopelev - Dmitry Sologdin and Lev Rubin.

In December 1948, his wife divorced Solzhenitsyn in absentia.

In May 1950, due to a disagreement with the leadership of the Sharashka, Solzhenitsyn was transferred to Butyrka prison, from where in August he was sent to Steplag, a special camp in Ekibastuz. Alexander Isaevich served almost a third of his prison camp term - from August 1950 to February 1953 - in the north of Kazakhstan. In the camp I worked in “general” work, for some time as a foreman, and took part in a strike. Later, camp life will receive literary embodiment in the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, and the prisoner strike - in the film script “Tanks Know the Truth”.

In the winter of 1952, Solzhenitsyn was diagnosed with a cancerous tumor and was operated on in the camp.

In conclusion, Solzhenitsyn became completely disillusioned with Marxism, over time he believed in God and leaned towards Orthodox-patriotic ideas (complete denial of communist ideology, the dissolution of the USSR and the creation of a Slavic state on the territory of Russia, Belarus and part of Ukraine, the establishment of an authoritarian system in the new state with a gradual transition towards democracy, channeling resources future Russia on the spiritual, moral and religious development of the people, primarily Russians). Already in the "sharashka" he returned to writing, in Ekibastuz he composed poems, poems ("Dorozhenka", "Prussian Nights") and plays in verse ("Prisoners", "Feast of the Winners") and memorized them.

After his release, Solzhenitsyn was sent into exile in a settlement “forever” (the village of Berlik, Kokterek district, Dzhambul region, southern Kazakhstan). He worked as a mathematics and physics teacher in grades 8-10 at the local secondary school named after Kirov.

By the end of 1953, his health had deteriorated sharply, an examination revealed a cancerous tumor, in January 1954 he was sent to Tashkent for treatment, and was discharged in March with significant improvement. The disease, treatment, healing and hospital impressions formed the basis of the story “Cancer Ward”, which was conceived in the spring of 1955.

Rehabilitation

In June 1956, by decision of the Supreme Court of the USSR, Solzhenitsyn was released without rehabilitation “due to the absence of corpus delicti in his actions.”

In August 1956 he returned from exile to Central Russia. Lives in the village of Miltsevo (Kurlovsky district, Vladimir region), teaches mathematics at the Mezinovskaya secondary school in Gus-Khrustalny district. Then he met his ex-wife, who finally returned to him in November 1956 (remarried on February 2, 1957).

Since July 1957 he lived in Ryazan, worked as an astronomy teacher at secondary school No. 2.

First publications

In 1959, Solzhenitsyn wrote the story “Shch-854” about the life of a simple prisoner from Russian peasants, in 1960 - the stories “A Village Is Not Worth Without a Righteous Man” and “The Right Brush”, the first “Little Ones”, the play “The Light That Is in You” (“Candle in the Wind”). He went through a certain crisis, seeing the impossibility of publishing his works.

In 1961, impressed by the speech of Alexander Tvardovsky (editor of the magazine “New World”) at the XXII Congress of the CPSU, he gave him “Shch-854”, having previously removed from the story the most politically sensitive fragments that were obviously not passable by Soviet censorship. Tvardovsky appreciated the story extremely highly, invited the author to Moscow and began to push for the publication of the work. N. S. Khrushchev overcame the resistance of Politburo members and allowed the publication of the story. The story entitled “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” was published in the magazine “New World” No. 11, 1962, immediately republished and translated into foreign languages.

Soon after this, “A village does not stand without a righteous man” (under the title “Matryonin’s Dvor”) and “An Incident at Kochetovka Station” (under the title “An Incident at Krechetovka Station”) were published in the magazine “New World” (No. 1, 1963).

The first publications evoked a huge number of responses from writers, public figures, critics and readers. Letters from readers - former prisoners (in response to “Ivan Denisovich”) laid the foundation for “The Gulag Archipelago.”

Solzhenitsyn's stories stood out sharply against the background of the works of that time with their artistic merit and civic courage. This was emphasized by many at that time, including writers and poets. Thus, Varlam Shalamov wrote in a letter to Solzhenitsyn in November 1962:

A story is like poetry—everything in it is perfect, everything is purposeful. Every line, every scene, every characteristic is so laconic, smart, subtle and deep that I think that “New World” has not published anything so integral, so strong since the very beginning of its existence.

In the summer of 1963, he created the next, fifth, truncated “for censorship” edition of the novel “In the First Circle,” intended for publication (of 87 chapters). Four chapters from the novel were selected by the author and offered to the New World " ...for testing, under the guise of “Excerpt”...».

December 28, 1963 editorial office of the magazine “New World” and Central state archive literature and art nominated “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” for the Lenin Prize for 1964 (as a result of a vote of the Prize Committee, the proposal was rejected).

In 1964, for the first time, he submitted his work to samizdat - a cycle of “poems in prose” under common name "Tiny".

In the summer of 1964, the fifth edition of “In the First Circle” was discussed and accepted for publication in 1965 by Novy Mir. Tvardovsky gets acquainted with the manuscript of the novel “Cancer Ward” and even offers it to Khrushchev for reading (again through his assistant Lebedev). I had a meeting with Varlam Shalamov, who had previously spoken favorably about “Ivan Denisovich,” and invited him to work together on “Archipelago.”

In the fall of 1964, the play “Candle in the Wind” was accepted for production at the Lenin Komsomol Theater in Moscow.

“Tiny Things” penetrated abroad through samizdat and, under the title “Sketches and Tiny Stories,” was published in October 1964 in Frankfurt in the magazine “Grani” (No. 56) - this is the first publication in the foreign Russian press of Solzhenitsyn’s work, rejected in the USSR.

In 1965, with Boris Mozhaev, he traveled to the Tambov region to collect materials about the peasant uprising (during the trip, the name of the epic novel about the Russian revolution was determined - “The Red Wheel”), began the first and fifth parts of the “Archipelago” (in Solotch, Ryazan region and on the farm Kopli-Märdi near Tartu), finishes work on the stories “What a Pity” and “Zakhar-Kalita”, publishes in “ Literary newspaper».

On September 11, the KGB conducts a search at the apartment of Solzhenitsyn’s friend V.L. Teush, with whom Solzhenitsyn kept part of his archive. Manuscripts of poems, “In the First Circle”, “Little Ones”, plays “Republic of Labor” and “Feast of the Winners” were seized.

The Central Committee of the CPSU published in a closed edition and distributed among the nomenklatura, “ to incriminate the author", "Feast of the Winners" and the fifth edition of "In the First Circle". Solzhenitsyn writes complaints about the illegal seizure of manuscripts to the Minister of Culture of the USSR Demichev, the secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee Brezhnev, Suslov and Andropov, and transfers the manuscript of “Circle-87” for storage in the Central State Archive of Literature and Art.

Four stories were proposed to the editors of “Ogonyok”, “October”, “Literary Russia”, “Moscow” - but were rejected everywhere. The newspaper "Izvestia" typed the story "Zakhar-Kalita" - the finished set was scattered, "Zakhar-Kalita" was transferred to the newspaper "Pravda" - refusal by N. A. Abalkin, head of the department of literature and art.

Dissidence

Already by March 1963, Solzhenitsyn had lost Khrushchev’s favor (non-awarding of the Lenin Prize, refusal to publish the novel “In the First Circle”). After Brezhnev came to power, Solzhenitsyn practically lost the opportunity to legally publish and speak. In September 1965, the KGB confiscated Solzhenitsyn's archive with his most anti-Soviet works, which worsened the writer's situation. Taking advantage of a certain inaction of the authorities, in 1966 he began an active social activities(meetings, speeches, interviews with foreign journalists). At the same time, he began distributing his novels “In the First Circle” and “Cancer Ward” in samizdat. In February 1967 he secretly graduated artistic research"GULAG Archipelago".

In May 1967, he sent out a “Letter to the Congress” of the USSR Writers’ Union, which became widely known among the Soviet intelligentsia and in the West. After the “Letter,” the authorities began to take Solzhenitsyn seriously. In 1968, when in the USA and Western Europe The novels “In the First Circle” and “Cancer Ward” were published, which brought popularity to the writer; the Soviet press began a propaganda campaign against the author. In 1969, Solzhenitsyn was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. The prize was not awarded to him, but soon after that he was expelled from the Union of Writers of the USSR. After his expulsion, Solzhenitsyn began to openly declare his Orthodox patriotic beliefs and sharply criticize the authorities. In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was again nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and this time the prize was awarded to him. The writer emphasized political aspect awarding the prize, although the Nobel Committee denied this. A powerful propaganda campaign against Solzhenitsyn was organized in the Soviet media. The Soviet authorities offered Solzhenitsyn to leave the country, but he refused.

Back in August 1968, he met Natalya Svetlova, and they began an affair. Solzhenitsyn began to seek a divorce from his first wife. With great difficulty, the divorce was obtained on July 22, 1972. Soon Solzhenitsyn managed to register his marriage with Svetlova, despite the opposition of the authorities (the marriage gave him the opportunity to register in Moscow).

The USSR launched a powerful propaganda campaign against dissidents. September 24 KGB via ex-wife Solzhenitsyn offered the writer the official publication of the story “Cancer Ward” in the USSR in exchange for refusing to publish “The Gulag Archipelago” abroad. (In her later memoirs, Natalya Reshetovskaya denies the role of the KGB and claims that she tried to achieve an agreement between the authorities and Solzhenitsyn on her personal initiative.) However, Solzhenitsyn, having said that he did not object to the printing of “Cancer Corps” in the USSR, did not express a desire to bind himself to the secret agreement with the authorities. (Various descriptions of related events are found in Solzhenitsyn’s book “The Calf Butted an Oak Tree” and in the memoirs of N. Reshetovskaya “APN - I am Solzhenitsyn”, published after Reshetovskaya’s death.) In late December 1973, the publication of the first volumes of "The Gulag Archipelago". In Soviet means mass media a massive campaign began to denigrate Solzhenitsyn as a traitor to the motherland with the label of “literary Vlasovite.” The emphasis was not on the actual content of “The Gulag Archipelago” (an artistic study of the Soviet camp-prison system 1918-1956), which was not discussed at all, but on Solzhenitsyn’s solidarity with “traitors to the motherland during the war, policemen and Vlasovites.”

In the USSR, during the years of stagnation, “August the Fourteenth” and “The Gulag Archipelago” (like the first novels) were distributed in samizdat.

Exile

On January 7, 1974, the release of the “Gulag Archipelago” and measures to “suppress anti-Soviet activities” of Solzhenitsyn were discussed at a meeting of the Politburo. The issue was brought to the Central Committee of the CPSU, Yu. V. Andropov and others spoke in favor of expulsion; for arrest and exile - Kosygin, Brezhnev, Podgorny, Shelepin, Gromyko and others. Andropov's opinion prevailed.

On February 12, Solzhenitsyn was arrested, accused of treason and deprived of Soviet citizenship. On February 13, he was expelled from the USSR (delivered to Germany by plane). On March 29, the Solzhenitsyn family left the USSR. The assistant to the US military attache, William Odom, helped secretly take the writer’s archive and military awards abroad.

Soon after his expulsion, Solzhenitsyn committed short trip By Northern Europe, as a result, decided to temporarily settle in Zurich, Switzerland.

On March 3, 1974, the “Letter to the Leaders of the Soviet Union” was published in Paris; leading Western publications and many democratically minded dissidents in the USSR, including A.D. Sakharov, assessed the “Letter” as anti-democratic, nationalistic and containing “dangerous delusions”; Solzhenitsyn's relations with the Western press continued to deteriorate.

In the summer of 1974, using fees from the Gulag Archipelago, he created the Russian Public Fund for Assistance to the Persecuted and Their Families to help political prisoners in the USSR (parcels and money transfers to places of detention, legal and illegal material aid families of prisoners).

In April 1975, he and his family traveled through Western Europe, then headed to Canada and the USA. In June-July 1975, Solzhenitsyn visited Washington and New York and made speeches at the Congress of Trade Unions and in the US Congress. In his speeches, Solzhenitsyn sharply criticized the communist regime and ideology, called on the United States to abandon cooperation with the USSR and the policy of détente; at that time the writer still continued to perceive the West as an ally in the liberation of Russia from “communist totalitarianism.”

In August 1975 he returned to Zurich and continued work on the epic “The Red Wheel”.

In February 1976, he toured Great Britain and France, by which time anti-Western motives had become noticeable in his speeches. In March 1976, the writer visited Spain. In a sensational speech on Spanish television, he praised Franco's recent regime and warned Spain against "moving too quickly towards democracy." Criticism of Solzhenitsyn intensified in the Western press, leading European and American politicians declared disagreement with his views.

In April 1976, he moved with his family to the United States and settled in the town of Cavendish (Vermont). After his arrival, the writer returned to work on “The Red Wheel,” for which he spent two months in the Russian emigrant archive at the Hoover Institution.

Back in Russia

With the advent of perestroika official attitude in the USSR, Solzhenitsyn’s creativity and activities began to change, many of his works were published.

On September 18, 1990, simultaneously in Literaturnaya Gazeta and Komsomolskaya Pravda, Solzhenitsyn’s article was published on the ways of reviving the country, on the reasonable, in his opinion, foundations for building the life of the people and the state - “How can we build Russia? Strong considerations." The article developed Solzhenitsyn’s long-standing thoughts, expressed earlier in his “Letter to the Leaders of the Soviet Union,” the article “Repentance and Self-Restraint as Categories of National Life,” and other prose and journalistic works. Solzhenitsyn donated the royalties for this article to the victims of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident. The article generated a huge number of responses.

In 1990, Solzhenitsyn was restored to Soviet citizenship.

The book “The Gulag Archipelago” was awarded a State Prize in 1990.

Together with his family, he returned to his homeland on May 27, 1994, flying from the USA to Vladivostok, traveling by train across the country and ending the trip in the capital. He spoke at the State Duma of the Russian Federation.

In the mid-1990s, by personal order of President Boris Yeltsin, he was given the Sosnovka-2 state dacha in Troitse-Lykovo. The Solzhenitsyns designed and built a two-story brick house there with a large hall, a glassed-in gallery, a living room with a fireplace, a concert grand piano and a library where portraits of Stolypin and Kolchak hang.

In 1997 he was elected full member Russian Academy Sci.

In 1998, he was awarded the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called, but refused the award: “I cannot accept the award from the supreme power that brought Russia to its current disastrous state.”

Awarded the Great Gold Medal named after M.V. Lomonosov (1998).

Awarded the State Prize Russian Federation for outstanding achievements in the field of humanitarian work (2006).

On June 12, 2007, President Vladimir Putin visited Solzhenitsyn and congratulated him on being awarded the State Prize.

The writer himself, soon after returning to the country, established a literary prize in his name to reward writers “whose work has high artistic merit, contributes to the self-knowledge of Russia, and makes a significant contribution to the preservation and careful development of the traditions of Russian literature.”

He spent the last years of his life in Moscow and at a dacha near Moscow.

Shortly before his death, he was ill, but continued to engage in creative activities. Together with his wife Natalya Dmitrievna, president of the Alexander Solzhenitsyn Foundation, he worked on the preparation and publication of his most complete, 30-volume collected works. After a serious operation he had undergone, the only thing that worked for him was right hand.

Death and burial

Solzhenitsyn’s last confession was received by Archpriest Nikolai Chernyshov, a cleric of the Church of St. Nicholas in Kleniki.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn died on August 3, 2008, at the age of 90, in his home in Trinity-Lykovo. Death occurred at 23:45 Moscow time from acute heart failure.

Stories and novellas

One day of Ivan Denisovich

Matryonin yard

Novels

Gulag Archipelago

Cancer building

In the first circle

Red wheel

Memoirs, essays, journalism

A calf butted heads with an oak tree

Russia in collapse

Living not by lies (essay)

Two hundred years together M., Russian way, 2001 (Studies of modern Russian history) ISBN 5-85887-151-8 (in 2 vols.)

How can we develop Russia (article)

Other

Russian language extension dictionary

Perpetuation of memory

On the day of the funeral, President of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree “On perpetuating the memory of A. I. Solzhenitsyn,” according to which, since 2009, personal scholarships named after A. I. Solzhenitsyn were established for students of Russian universities, the Moscow government was recommended to name one of the city streets after Solzhenitsyn, and the government of the Stavropol Territory and the administration of the Rostov region - to implement measures to perpetuate the memory of A.I. Solzhenitsyn in the cities of Kislovodsk and Rostov-on-Don.

On August 12, 2008, the Moscow government adopted a resolution “On perpetuating the memory of A. I. Solzhenitsyn in Moscow,” which renamed Bolshaya Kommunisticheskaya Street to Alexander Solzhenitsyn Street and approved the text of the memorial plaque. Some residents of the street protested its renaming.

In October 2008, the mayor of Rostov-on-Don signed a decree naming the central avenue of the Liventsovsky microdistrict under construction after Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

On September 9, 2009, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novel “The Gulag Archipelago” was included in the mandatory school curriculum in literature for high school students. Previously, the school curriculum already included the story "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich" and the story " Matrenin Dvor"The writer's biography is studied in history lessons.

Movies

“In the First Circle” (2006) - Solzhenitsyn himself is a co-author of the script and reads the text from the author.

“One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” (1970, Norway - England)

The literary debut of Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn took place in the early 60s, when the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” (1962, No. 11), the stories “An Incident at Kochetovka Station”, “Matrenin’s Dvor” (1963, No. 1). Unusuality literary destiny Solzhenitsyn is that he made his debut at a respectable age - in 1962 he was forty-four years old - and immediately declared himself as mature, independent master. “I haven’t read anything like this for a long time. Nice, clean, great talent. Not a drop of falsehood...” This is the very first impression of A.T. Tvardovsky, who read the manuscript of “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” at night, in one sitting, without stopping. And when meeting the author personally, the editor of Novy Mir said: “You wrote an excellent thing. I don’t know what schools you attended, but you came away a fully formed writer. We don’t have to teach or educate you.” Tvardovsky made incredible efforts to ensure that Solzhenitsyn's story saw the light of day.

Solzhenitsyn's entry into literature was perceived as " literary miracle”, which evoked a strong emotional response from many readers. One touching episode is noteworthy, which confirms the unusual nature of Solzhenitsyn’s literary debut. The eleventh issue of Novy Mir with the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” has gone to subscribers! And in the editorial office itself, this issue was being distributed to a select few lucky ones. It was a quiet Saturday afternoon. As A. T. Tvardovsky later talked about this event, it was like in church: everyone quietly came up, paid money and received the long-awaited number.

Readers welcomed the appearance of a new remarkable talent in literature. This is what Varlaam Shalamov wrote to Solzhenitsyn: “Dear Alexander Isaevich! I didn’t sleep for two nights - I read the story, reread it, remembered...

The story is like poetry! Everything in it is expedient. Every line, every scene, every characteristic is so laconic, smart, accurate and deep that, I think, “New World” has not published anything so integral, so strong from the very beginning of its existence.”

“I was stunned, shocked,” Vyacheslav Kondratyev wrote about his impressions. - Probably for the first time in my life I realized so truly, what could be true. It was not only the Word, but also the Deed.”

The story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” attracted the attention of readers not only with its unexpected theme and novelty of the material, but also with its artistic perfection. “You managed to find an exceptionally strong form,” Shalamov wrote to Solzhenitsyn. “The small form has been chosen - in this experienced artist", Tvardovsky noted. Indeed, in the early days of his literary activity, the writer gave preference to the short story genre. He adhered to his understanding of the nature of the story and the principles of working on it. “In a small form,” he wrote, “you can fit a lot, and it’s a great pleasure for an artist to work on small form. Because in a small form you can hone the edges with great pleasure for yourself.” And “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” Solzhenitsyn attributed to the short story genre: “Ivan Denisovich” is, of course, a story, albeit a big, loaded one.” The genre designation “story” appeared at the suggestion of Tvardovsky, who wanted to give the story “more weight.”

Annex 1

Testing knowledge on the previous topic "V.T. Shalamov. Life and art. "Kolyma Tales"

Shalamov's prose is not just memories, memoirs of a man who went through the circles of Kolyma hell. This is literature of a special kind, “new prose,” as the writer himself called it.

The works and life of Varlam Shalamov clearly reflect the fate of the intelligentsia during times of great repression. We should not reject literary works like "Kolyma Tales" - they should serve as an indicator for the present (especially considering the degradation that is happening in people's minds and which is so clearly visible through the quality of today's culture).

Shalamov's decision to describe the "life" of prisoners in concentration camps, which clearly reflects the Stalinist dictatorship, - heroic deed. “Remember, the most important thing: the camp is a negative school from the first to the last day for anyone. A person - neither a boss nor a prisoner - does not need to see him. But if you have seen him, you must tell the truth, no matter how terrible it is. On my part, I decided long ago that I would devote the rest of my life to this truth,” Shalamov wrote.

Exercise. Tell the biography of V.T. Shalamov, retell any story from the collection “Kolyma Stories”.

Basic criteria for assessing an oral response in literature

"EXCELLENT": awarded for a comprehensive, accurate answer, excellent knowledge of the text and other literary materials, the ability to use them for argumentation and independent conclusions, fluency in literary terminology, skills in analyzing a literary work in the unity of form and content, the ability to express one’s thoughts consistently with the necessary generalizations and conclusions , expressively read program works by heart, speak correct literary language.

"FINE": awarded for an answer that reveals good knowledge and understanding of literary material, the ability to analyze the text of a work, providing the necessary illustrations, the ability to express one’s thoughts consistently and competently. The answer may not fully develop the argumentation, there may be some difficulties in formulating conclusions, illustrative material may not be presented sufficiently, there may be some errors in memorizing and some errors in the speech formatting of statements.

"SATISFACTORILY": is awarded for an answer in which the material is mostly correct, but schematically or with deviations from the sequence of presentation. Analysis of the text is partially replaced by retelling, there are no generalizations and conclusions in full, there are significant errors in the speech format of statements, and there are difficulties in reading by heart.

"UNSATISFACTORY": placed if ignorance of the text or inability to analyze it is shown, if analysis is replaced by retelling; the answer lacks the necessary illustrations, there is no logic in the presentation of the material, there are no necessary generalizations and independent assessment of the facts; skills are insufficiently developed oral speech, there are deviations from the literary norm.

Appendix 2

Assignments to consolidate knowledge (independent work of studentsbased on the work “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”)

1. Why was A. I. Solzhenitsyn’s literary debut perceived as an Event, as a “literary miracle”?

2. Give readers’ reviews of Solzhenitsyn’s prose. Please comment on them.

3. Why does the writer prefer the short story genre?

4. How was Solzhenitsyn’s own camp experience reflected in the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”?

6. Comment on the clash scenes: Buinovsky - Volkovoy, foreman Tyurin - foreman Der

7. Reveal the moral implications of the situations: Shukhov - Caesar.

8. What role do the biographies of the characters play in the story?

9. How does Solzhenitsyn convince that he dates the history of totalitarianism not from 1937, but from the first post-October years?

Application3

CRITERIA FOR READING BY MART (for a poetic moment)

2. Reading accuracy.

3. Expressiveness of reading (is logical stress and pauses placed correctly, is intonation chosen correctly, reading pace and voice strength).

4. Effective use of facial expressions and gestures.

ASSESSMENT

"5" - all criteria requirements are met

"4" - one of the requirements is not met

"3" - two of the basic requirements are met

Lesson on the works of A.I. Solzhenitsyn.

The tragic fate of a person in a totalitarian state (based on the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”) 11th grade

Lesson design: slides - portrait of the writer, reviews of the writer, exhibition of books, newspaper publications.

Lesson Objectives: to arouse interest in the personality and work of A.I. Solzhenitsyn, who became a symbol of openness, will and Russian directness; show the “unusual life material” taken as the basis for the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, and entice students to read the story; lead students to understand the tragic fate of man in a totalitarian state.

Solzhenitsyn became the oxygen of our non-

breathable time. And if society

ours, literature, first of all, still yes -

shat, then this is because lies work

Tsin furs pump air into the suffocating

Yusya, godless, almost losing herself,

Shuya Russia.

V.P.Astafiev

During the classes

Teacher's word.

None of the three “roles” suits him.

Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn is an outstanding Russian writer, publicist and public figure. His name became known in literature in the 60s of the 20th century, during the “Khrushchev Thaw”, then disappeared for many years.

He, Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn, dared to tell the truth about the terrible Stalinist time, to create works about camp life, works that made the author wildly popular.

The stories “Matrenin's Dvor”, “An Incident at Krechetovka Station”, the novel “In the First Circle”, the story “Cancer Ward” aroused the anger of “domestic officials” and ... brought the author world fame. And in 1970, A.I. Solzhenitsyn was awarded Nobel Prize on literature. It seemed that justice had prevailed.

...But on one February day in 1974, in connection with the release of the 1st volume of the book “GULAK Archipelago”), the writer was forcibly expelled from Russia. A plane carrying a single passenger landed in the German city of Frankfurt am Main.

Solzhenitsyn was 55 years old.

What is known about him?

Individual messages from students.

Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918 in Kiselevsk.

Mother Taisiya Zakharovna Shcherbak, the daughter of a wealthy farmer in the Kuban, received an excellent upbringing and education: she studied in Moscow at the agricultural courses of the book. Golitsyna.

In 1924, Taisiya Zakharovna and her six-year-old son moved to Rostov-on-Don.

At school, young Alexander Solzhenitsyn is the head of the class, a desperate football player, a theater fan and a member of the school drama club.

2. A.I. Solzhenitsyn is a most educated person. He graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Rostov University. He studied in absentia at the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature, taught astronomy and mathematics in one of the schools in the city of Morozovsk (not far from Rostov).

In 1041, A.I. Solzhenitsyn became a soldier, then a cadet at an officer school in the city of Kostroma.

He traveled along front-line roads from Orel to East Prussia.

This is the combat description General Travkin gave to the commander of the “sound battery” Solzhenitsyn: “... Solzhenitsyn was personally disciplined, demanding... Carrying out combat missions, he repeatedly showed personal heroism, carrying the personnel along with him, and always emerged victorious from mortal dangers.”

For his courage (after the capture of Orel), Solzhenitsyn received the Order of the Patriotic War, 2nd degree. The Order of the Red Star (after the capture of Bobruisk) is the second front-line award.

And suddenly... arrest, eight years in the camps of the ominous “GULAK archipelago” cordoned off with barbed wire. (Solzhenitsyn came under the supervision of military counterintelligence for corresponding with his youth friend Nikolai Vitkevich). Fate decreed that the future writer went through all the “circles of prison hell” and witnessed the uprising of prisoners in Ekibastuz. Exiled to Kazakhstan “forever”, having composed several works (in his head), and planning a huge novel about Russia, Solzhenitsyn suddenly learned that he was terminally ill.

In 1952, a camp doctor operated on Solzhenitsyn for a malignant tumor in the groin. But the struggle for life is not over. Soon a cancerous tumor was discovered in the stomach. “That winter I arrived in Tashkent already dead. That's why I came here - to die. And they brought me back to live some more,” Solzhenitsyn wrote in his story “The Right Hand.” And the disease subsided.

Subsequently, Solzhenitsyn admitted that up to today I’m sure: “While I’m writing, I’m on a reprieve.”

3. Literary debut of A.I. Solzhenitsyn. When the writer was well over forty, the magazine “New World” (1962) published the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” which immediately became a classic “ camp prose" Initial publication of the story “Shch-854 (One Day of One Prisoner).”

A.T. Tvardovsky (at that time Chief Editor magazine “New World”) wrote: “The life material underlying A. Solzhenitsyn’s story is unusual... It carries an echo of those painful phenomena in our development associated with the period of the debunked cult... cult of personality...”

Tvardovsky highly appreciated the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”: “This is not a document in the memoir sense, not notes or memories of the author’s personal experiences... This is a work of art, and due to the artistic illumination of this life material, it is evidence of “special value, a document of art "

This “document of art” was written in just over a month.

“The image of Ivan Denisovich was formed from the soldier Shukhov, who fought with the author in the Soviet-German war (and never went to prison), the general experience of prisoners and the author’s personal experience in the Special Camp. The rest of the people are all from camp life, with their authentic biographies.” (P. Palamarchuk).

3. A brief retelling of the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

January. 1951

4. We think and reflect on the pages we read.

1. Who is Ivan Denisovich Shukhov? What's his problem? What is the fault?

Shukhov worked and lived in the village of Temgenevo, was married and had two children. But the Great Patriotic War began, and he became a soldier. “And this is how it was: in February 1942, their entire army was surrounded in the North-West... And so little by little the Germans caught them in the forests and took them... Shukhov was held captive for a couple of days.” Miraculously, he got to his people, but he was accused of treason and put behind bars. Shukhov carried out a task for German intelligence. “What kind of task this was, neither Shukhov himself nor the investigator could come up with. So they just left it as a task.”

What awaited the hero of the story if he had not signed the “deed”?

Shukhov chose life by signing documents against himself. Even if it’s a camp life, painful and difficult, it’s still life.

3.What is life like in the camp? How does Ivan Denisovich behave? Let's observe the camp reality.

Shukhov was sentenced to eight years in the camps. At five o'clock in the morning the camp wakes up. A cold barracks, in which “not every light was on, where two hundred people slept on fifty bedbug-lined carriages.”

Kitchen. The prisoners eat their meager gruel with their hats on. “The most well-fed time for campers is June: every vegetable runs out and is replaced with cereals. The worst time is July: nettles are whipped into a cauldron.” Sometimes they give you porridge from magara. “Magara is not only cold, but even hot it leaves neither taste nor satiety: grass and grass, only yellow, looking like millet... Porridge is not porridge, but goes for porridge.”

It's freezing outside, taking your breath away. And Tyurin’s brigade, which includes Shukhov, is getting ready to go to work... Endless checks and inspections.

Ivan Denisovich Shukhov is a jack of all trades. He is a mason, a carver, and a stove maker. Works with passion without feeling the cold. This is how the author describes the prisoner: “Shukhov masterfully grabs the smoking solution... He throws exactly as much solution as under one cinder block. And he grabs a cinder block from the pile (but grabs it carefully - don’t worry about tearing your mitten, tearing cinder blocks hurts). And having masterfully leveled the mortar, he plopped a cinder block in there... And it was already grabbed, frozen...

But they (the prisoners) did not stop for a moment and drove the masonry further and further..."

Shukhov not only lives (just to survive), but in order to maintain self-respect. He doesn’t inform on his fellow prisoners, he doesn’t humiliate himself because of tobacco, he doesn’t lick other people’s plates... He takes care of his bread and carries it in a special pocket.

4. What character traits does the author value in Ivan Denisovich? And you?

The main character of the story, having gone through trials, managed to preserve the traits inherent in his character, characteristic of a Russian peasant: conscientiousness, hard work, human dignity.

Senka Klevshin. He was captured and escaped three times, but was “caught.” Even in Buchenwald, “he miraculously deceived death, now he is serving his sentence quietly.”

Baptist Alyoshka and captain and captain Buinovsky have been in prison for 25 years;

Brigadier Tyurin is in the camp because his father was registered as a kulak.

There is an Estonian who was taken to Sweden as a child and returned to his homeland as an adult.

Film director Caesar Markovich... Sixteen-year-old boy Gopchik... Kolya Vdovushkin, former student Faculty of Literature And many, many others!

6. A. Solzhenitsyn wrote the camp world one day. And what?

The hero of the story considered the day successful, almost happy.

“That day he (Shukhov) had a lot of successes: he wasn’t put in a punishment cell, the brigade wasn’t sent to Sotsgorodok... the foreman closed the interest well, Shukhov laid the wall cheerfully, he didn’t get caught with a hacksaw on a search... And he didn’t get sick, he overcame it. The day passed, unclouded, almost happy.”

Days like these make it scary.

7. Who is to blame for the Shukhov tragedy? And other thousands of people?

5. Generalization

No, it is impossible for prisoners to achieve justice and truth. It is useless and pointless in the “upgrade your rights” camp. People are beginning to realize that what happened to them is not just mistakes, it is a well-thought-out system of repression - the tragedy of an entire generation.

6. Homework

Write your thoughts about the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

Rental block

RESPONSE PLAN

1. Exposing the totalitarian system.

2. Heroes of “Cancer Ward”.

3. The question of the morality of the existing system.

4. Choice of life position.

1. The main theme of A. I. Solzhenitsyn’s work is the exposure of the totalitarian system, proof of the impossibility of human existence in it. His work attracts the reader with its truthfulness, pain for a person: “...Violence (over a person) does not live alone and is not capable of living alone: it is certainly intertwined with lies,” Solzhenitsyn wrote. - And you need to take a simple step: do not participate in lies. Let this come into the world and even reign in the world, but through me.” More is available to writers and artists - to defeat lies.

In his works “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, “Matryonin’s Yard”, “In the First Circle”, “The Gulag Archipelago”, “Cancer Ward” Solzhenitsyn reveals the whole essence of a totalitarian state.

2. In “Cancer Ward”, using the example of one hospital ward, Solzhenitsyn depicts the life of an entire state. The author manages to convey the socio-psychological situation of the era, its originality on such seemingly small material as an image of the life of several cancer patients who, by the will of fate, found themselves in the same hospital building. All heroes are not easy different people With different characters; each of them is a bearer of certain types of consciousness generated by the era of totalitarianism. It is also important that all the heroes are extremely sincere in expressing their feelings and defending their beliefs, as they are faced with death. Oleg Kostoglotov, a former prisoner, independently came to reject the postulates of the official ideology. Shulubin, Russian intellectual, participant October revolution, surrendered, outwardly accepting public morality, and doomed himself to a quarter of a century of mental torment. Rusanov appears as the “world leader” of the nomenklatura regime. But, always strictly following the party line, he often uses the power given to him for personal purposes, confusing them with public interests.

The beliefs of these heroes are already fully formed and are repeatedly tested during discussions. The remaining heroes are mainly representatives of the passive majority who have accepted official morality, but they are either indifferent to it or do not defend it so zealously.

The entire work represents a kind of dialogue in consciousness, reflecting almost the entire spectrum of life ideas characteristic of the era. The external well-being of a system does not mean that it is deprived internal contradictions. It is in this dialogue that the author sees a potential opportunity to cure the cancer that has affected the entire society. Born in the same era, the heroes of the story do different things life choice. True, not all of them realize that the choice has already been made. Efrem Podduev, who lived his life the way he wanted, suddenly understands, turning to Tolstoy’s books, the entire emptiness of his existence. But this hero’s insight is too late. In essence, the problem of choice faces every person every second, but out of many solution options, only one is correct, out of all life paths only one to my heart.

Demka, a teenager at a crossroads in life, realizes the need for choice. At school he absorbed the official ideology, but in the ward he felt its ambiguity, hearing the very contradictory, sometimes mutually exclusive statements of his neighbors. The clash of positions of different heroes occurs in endless disputes affecting both everyday and existential problems. Kostoglotov is a fighter, he is tireless, he literally pounces on his opponents, expressing everything that has become painful over the years of forced silence. Oleg easily fends off any objections, since his arguments are hard-won by himself, and the thoughts of his opponents are most often inspired by the dominant ideology. Oleg does not accept even a timid attempt at compromise on the part of Rusanov. And Pavel Nikolaevich and his like-minded people are unable to object to Kostoglotov, because they are not ready to defend their convictions themselves. The state has always done this for them.

Rusanov lacks arguments: he is used to realizing that he is right, relying on the support of the system and personal power, but here everyone is equal in the face of imminent and imminent death and in front of each other. Kostoglotov’s advantage in these disputes is also determined by the fact that he speaks from the position of a living person, while Rusanov defends the point of view of a soulless system. Shulubin only occasionally expresses his thoughts, defending the ideas of “moral socialism.” It is precisely the question of the morality of the existing system that all the disputes in the House ultimately revolve around.

From Shulubin’s conversation with Vadim Zatsyrko, a talented young scientist, we learn that, in Vadim’s opinion, science is only responsible for the creation of material wealth, and moral aspect the scientist should not worry.

Demka’s conversation with Asya reveals the essence of the education system: from childhood, students are taught to think and act “like everyone else.” The state, with the help of schools, teaches insincerity and instills in schoolchildren distorted ideas about morality and ethics. In the mouth of Avietta, Rusanov’s daughter, an aspiring poetess, the author puts official ideas about the tasks of literature: literature must embody the image of a “happy tomorrow”, in which all the hopes of today are realized. Talent and writing skill, naturally, cannot be compared with ideological demands. The main thing for a writer is the absence of “ideological dislocations,” so literature becomes a craft serving the primitive tastes of the masses. The ideology of the system does not imply the creation moral values, for which Shulubin, who betrayed his convictions, but did not lose faith in them, yearns. He understands that a system with a shifted scale life values not viable.

Rusanov’s stubborn self-confidence, Shulubin’s deep doubts, Kostoglotov’s intransigence - different levels personality development under totalitarianism. All these life positions are dictated by the conditions of the system, which thus not only forms an iron support for itself from people, but also creates conditions for potential self-destruction. All three heroes are victims of the system, since it deprived Rusanov of the ability to think independently, forced Shulubin to abandon his beliefs, and took away freedom from Kostoglotov. Any system that oppresses an individual disfigures the souls of all its subjects, even those who serve it faithfully.

3. Thus, the fate of a person, according to Solzhenitsyn, depends on the choice that the person himself makes. Totalitarianism exists not only thanks to tyrants, but also thanks to the passive and indifferent majority, the “crowd”. Only choice true values can lead to victory over this monstrous totalitarian system. And everyone has the opportunity to make such a choice.

We have the largest information database in RuNet, so you can always find similar queries