Symbol of the image of the road of life. The Russian way of Nikolai Rubtsov0

A symbol of the life path, the path of the soul to the afterlife, especially significant in transitional rituals; a place where fate, fate, and luck of a person are manifested in his meetings with people, animals and demons. D. is a type of border between “one’s own” and “alien” space; mythologically “unclean” place. Crossings of two or more roads, forks and roadsides are especially dangerous. It was customary for the Eastern Slavs to bury suicides, unbaptized children and other unclean dead at crossroads. D., along with boundaries and other boundaries, is the place where mythological characters appear. The Poles believed that sinful human souls resided in D.'s ruts. Demons appear especially often in D., leading a person astray: among Russians - goblin, among Western Ukrainians - fornication, wild woman, among Serbs invisible demons are worse, among Western Slavs- will-o'-the-wisps originating from the souls of the “unclean” dead; among the Kashubians there is a swamper who, illuminating the D. with a lantern, calls: “Here is the way home, here is the way home...” Throwing various objects onto the D. is a way of ritually removing dangerous and harmful substance outside of “its” space and its destruction. In D., “unclean” objects are trampled, smashed, and pulled apart by feet, dividing harm and danger into many parts. When treating diseases, the Russians threw away the nails and hair of the patient, as well as objects to which the disease was “transferred” with the help of a spell. Throwing objects onto D. could also be an act of harmful magic, designed to transmit damage or illness to another person, therefore there was a ban on lifting found things onto D. and even touching them. One of the options for ritual destruction is to throw objects over the D. that need to be disposed of. In particular, in Russia and Polesie, to get rid of bedbugs and cockroaches, they were thrown across D. in a box or transported in an old bast shoe. At the same time, it was believed that objects accidentally found on D. had healing powers and brought happiness to the person who found them. For example, to get rid of warts, Ukrainians tried to find an old shoe and, without leaving the spot, throw it over their heads. Objects were left on the D. or hung near it for productive and protective purposes. For example, to ward off epidemics and epizootics, ordinary towels were hung on roadside crosses. In magical practice, in wedding rituals, etc., symbolic blocking of the D. was practiced. For example, in the Polish Tatras, a shepherd, when driving his flock out of the village to the pasture, drew a border across the D. to block the path evil spirits. IN wedding ceremony When the newlyweds returned from the wedding, they blocked the D. with logs, rope, ribbons, etc., demanding a ransom from the groom for the right to travel on the wedding train. Among the Eastern and Western Slavs, blocking the door with stolen things, logs, and firewood was one of the types of ritual outrages. Crossing the road for people or livestock was practiced to take away health, happiness, and fertility. The Eastern Slavs and Bulgaria believed that milk could be taken away from cows by giving them milk. Plowing and harrowing the farm for ritual purposes served to activate fertile forces. In the Czech Republic, among the Croats and Slovenes, on Maslenitsa, mummers imitated plowing and sat down, dragging a plow and a harrow through the streets. In Polesie, plowing and harrowing was one of the ways of causing rain. The Eastern Slavs believed that it was impossible to build a house in the place where D. passed: living in such a house would be restless, and also on D. one should not sleep, sit, sing or shout loudly, or perform natural necessities.

The theme of the road in the lyrics of the master of Russian poetry of the second half of the twentieth century

The work of the poet Nikolai Mikhailovich Rubtsov firmly won the hearts of the Russian people. His poems leave indelible traces in the soul of a thoughtful reader, from which a life-long road is formed.

The theme of the road is present in the works of many writers. For Rubtsov, it is connected, first of all, with the turning points of his life. He was always “on the road”: searching for himself and creating new poetic images. Poems were born on the fly; he thought them over carefully, and wrote down only ready-made options on paper. “He truly lived like a bird. I fell asleep where night fell. Woke up from a random rustle or blow of wind; he was easy-going and tireless on endless flights from place to place,” the Vologda poet Viktor Korotaev wrote about Nikolai Mikhailovich.

Yuri Seleznev in the article “Before the Big Road” noted: “... He [Rubtsov - N.D.] felt that his work itself was not yet a big road, but already its plantains.” The poet devoted his entire life to literary creativity: he was not interested in material wealth, because the main treasure of his life was poetry. In his poems, he sought to convey all the colors and manifestations of the surrounding world as figuratively and poetically as possible.

Vladimir Gusev in the book “The Unobvious: Yesenin and Soviet Poetry” writes that “Rubtsov, following Yesenin, comes from the feeling that harmony reigns in the world, which should be demonstrated... It is, first of all, in nature, in accordance with nature, and not contrary to nature - this is the undeclared but unshakable motto of Yesenin and Rubtsov. It is in everything connected with nature: in the village and its values, in the integral feeling, in the melodic and melodious-rhythmic beginning of the world, as the beginning of natural harmony.”

In many poems by Nikolai Mikhailovich, the river symbolizes life path, the road of great hopes and new discoveries. She is either worried “before the big road” (“I am happy with literally everything!”), or “brings heavenly light” (“In the Wilderness”).

“It can hardly be called accidental that more than a third of all Rubtsov’s poems are in one way or another connected with the image of the “path-road,” wrote Yuri Seleznev. - But if we take into account that the unnamed image of “paths and roads” secretly appears in other poems by Rubtsov, if we remember the constancy of the themes and images of separations, farewells, meetings and returns, departures, “sailing into the distance,” winds and blizzards , flying leaves and passing years, “images of loss,” if you do not forget that over all this poetic world of Rubtsov a “lonely wandering star” shines, then it is not easy to give up the idea that it is the road of life, the choice of path, that is the main one, central theme poetic consciousness of Nikolai Rubtsov."

In his autobiography, Rubtsov noted: “I especially love the themes of homeland and wanderings, life and death, love and daring.” The feeling of homelessness accompanied him all his life, from childhood. The image of the poet's house is the subject of an impossible dream (“Don't buy me a hut over the ravine...”). Being very young, the poet sadly exclaimed: “I’ve been wandering around the planet for so many years! // And I still have no shelter..."

Much later, in the poem “By the Blurred Road,” the poet turns to himself, sadly summing up the path traveled: “Why am I standing by the washed-out road and crying? // I cry that my best years have passed..."

Rubtsov’s latest collection of poems is called “Plantains”. It was published after the tragic death of the poet and included poems from the books “Lyrics”, “Star of the Fields”, “The Soul Keeps”, “The Noise of Pines” and “Green Flowers”.

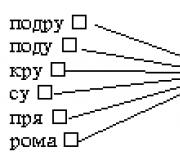

The “road” theme is found in Nikolai Mikhailovich in many poems: “ old road", "There is a procession", "On the way from home", "On the road", "Farewell song". The poem “Plantains” contains folklore motifs: “Top and tramp from bush to bush - // Not a bad streak in life.” Ring composition, giving this poem special completeness, speaks of eternity.

In the poetic lines “A road ran to Ustyug // Through the city of Totma and forests...” the author, paying attention to spatial boundaries, draws before the reader’s eye the road along which the convicts passed.

According to the doctor philological sciences Nichiporova I.B., “the poems “Plantains”, “Road Elegy”, the figurative world of which is generously colored with folklore flavor (“The road ran to Ustyug // Through the city of Totma and the forests ...”), are notable for the multiplicity of subjects of lyrical experience. These are animate plantains - silent and thoughtful witnesses of human dramas, and “tramps and prison guards” who entrusted their crying and laughter to the roads, and, finally, the lyrical hero himself, for whom the “torment of the road”, his native northern landscapes serve as a container of mental pain, “cautious” loneliness, and a healing introduction to the metaphysical dimension, collective experience, rooted in the depths of primordial memory: “Except from bush to bush // In the footsteps of long-dead souls // I will go, so that my thoughts can reach Ustyug // Immerse myself in the fabulous wilderness "".

It is interesting that in these two poems the plantains are presented as “dejected.” The symbolism of the image is emphasized by personification: the poet shows that the representative flora empathizes with a person: “Weary in the dust // I am dragging along like a prison guard, // It’s getting dark in the distance, // The plantain is depressed...”.

According to the dictionary of symbols, the plantain in Christianity personifies the path of Christ. In Renaissance art, it symbolizes the pilgrims who walked the path of Christ to Golgotha in the Holy Land. IN poetic world Rubtsov, the image of plantains has a very narrow symbolic meaning. Plantain is a grass that grows along the sides of roads, and convicts who are on the sidelines of life walk along the roads of Russia: “The plantains are sad today...”.

In the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language S.I. Ozhegov’s lexeme “podorozhny” is interpreted as “located by the road”. In the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language V.I. Dahl “road - related to the road, path, crossroads or trip.”

The theme of the road in Rubtsov’s lyrics is an expression of the wanderings and wanderings of the Russian person in time and space. Internal “wandering” was inherent in the poet’s creative nature: “Rubtsov loved the suddenness of acquaintances and partings. He appeared in places where he was not expected, and escaped from places where he was needed. It was this inconsistency of the wandering soul that carried him, led him through Rus',” poetess Valentina Igosheva wrote about the hero of our article.

In the early poems of Nikolai Rubtsov, this theme was revealed in lines about new meetings with people, new feelings and attitudes. But in 1970, a year before his death, the poet would write the already mentioned “Road Elegy,” which is permeated with a painful feeling of loneliness and loss, longing for loved ones and kindred souls, thoughts that “ best time// Further and further, more and more deafening.” All that remained from previous aspirations was “road pain”, promising nothing ahead except fatigue and despondency.

As follows from the memoirs of his contemporaries, Nikolai Mikhailovich loved life and wanted to live, but several years before his death he foresaw its coming. He even accidentally mentioned that if he died, he would take with him a whole book of unknown poems.

To summarize, we note that the image of the road was considered by Nikolai Rubtsov through the prism of views on own life and the life of the Russian people.

Bibliography:

1. Gusev V. Unobvious: Yesenin and Soviet poetry. - M., 1986. - P. 575

2. Zaitsev V. Nikolay Rubtsov. To help teachers, high school students and applicants / V.A. Zaitsev. - M.: Moscow State University Publishing House, 2002. - 86 p.

3. Igosheva V. N.M. Rubtsov. Wanderer or wanderer? Part IV: // Proza.ru URL: http://www.proza.ru/2009/12/25/1381 (Access date: 04/14/2017).

4. Korotaev V. One, but fiery passion // “Visions on the Hill”: a collection of articles - M.: Soviet Russia, 1990.

5. Nichiporov, I.B. “So I fell in love with the ancient roads...”: road motifs in the lyrics of N. Rubtsov // North. - 2016. - No. 11-12. — P. 55.

6. Ozhegov S.I. Explanatory dictionary of the Russian language. - M.: Russian language, 1988.

7. Romanov A. Sparks of memory // Poems, letters, memoirs of contemporaries / Rubtsov N.M. - M.: Eksmo, 2002. - P. 304.

8. Rubtsov N.M. Plantains / Compiled and author of the preface Viktor Korotaev. - M.: Young Guard, 1976.

9. Rubtsov N.M. Poetry. - Rostov n/d: Phoenix, 1998. - 384 p.

In the Slavic and especially in the Russian conceptual and verbal pictures of the world, the concepts of P, D and the layer of vocabulary denoting them also occupy a very important place.

For the Russian ethnic group, movement has always played a significant role in life; the process of settlement and development of vast territories is not completed at the present time. Russians are a moving ethnic group with a sedentary self-awareness. From time immemorial, in the life of Russians there were wanderers, “walkers”, wandering pilgrims, “rogues”, peddlers, otkhodniks, hunters, runaway peasants and convicts, ushkuiniki and robbers, coachmen who went on long-distance carriages, settlers who went looking for someone and where “it’s good to live in Rus'” - all those Russian people whose life was connected with constant wanderings, movements along the roads of a huge country.

The concept of P, D is present at various levels of culture, old and new, traditional folk and intellectual elite, in rites and rituals, in folklore of various genres, in high and church literature, in artistic poetic and prose works, in painting, music, etc. The entire set of concepts, images, symbols associated with the idea of the path, the cultural languages that serve to convey this conceptual complex, form a “mythologem of the path”, invariably and tangibly present in our collective national consciousness.

This is evidenced, in particular, by the increased use of the image of P, D in modern poetry and the song genre. From the middle, even from the first third of our century, P, D and the symbolism associated with them turn out to be especially attractive to our consciousness. In the newest, often ridiculous and hastily made one-day songs, the image of the road with its disorder, chaos, and conflict is one of the most popular: “Road, road, You know so much about my difficult life...”; “Somewhere far away trains are flying, Planes are going astray...”; “By the highway of his wanderings, By the highway of his lamentations...”, “The highway of my memories, In your fog I stand again...” (from modern songs), etc. The unsettledness, conflict, and homelessness of our lives have actualized in our subconscious the conceptual archetype D, P as a space of chaos opposing the stability of home, a space mastered by culture. The road is associated with wanderings, the search for fate, happiness, the road is a phantom that holds us captive in often meaningless movement, preventing us from moving on to the reasonable stability of life: “We have walked a hundred roads along and across... Only at our feet again lies the cursed circle of big roads.” (“Once again”); “With a long, long gray thread of worn-out roads we darn the wounds of the soul” (“Night Road”); “Forgive me, my country, that I live in captivity of the roads...” (“Snake”). The same surge in activity of the semiotic archetype P, D was observed during the Great Patriotic War: just remember the songs: “Eh, front-line paths” ..., “Eh roads, dust and fog ...”, K. Simonov’s poem “Do you remember, Alyosha, the roads of the Smolensk region ...”, which became a song, etc.

Despite many conceptual and semantic differences, P and D are united by their similar role in organizing the conceptual and linguistic model of the world in the spatiotemporal aspect. The fact of the primacy of understanding and expressing spatial relations in relation to temporal ones is well known (for example, prepositions of spatio-temporal meaning, the evolution of the semantics of some lexemes [time], etc.). The logical-linguistic and mythopoetic phenomenon of the chronotope has been sufficiently developed in poetics, when “time condenses and becomes a form of space, its new (“fourth”) dimension. Space, on the contrary, is “infected” with the internally intense properties of time (“temporization” of space), drawn into its breath.” In the facts of speech and language, this is manifested in the presence of spatio-temporal syncretism (for example, in lexemes ahead, behind, near, near, etc.). In the modern state, both lexemes - P and D - have the semantic property of spatio-temporal syncretism. It is found in microtexts - clichéd constructions, stable combinations different types, in separate word forms: on the way, on the road, on the road, dear. “To travel alone is a long road”; The road is long, but travelling (last), “The road is life-long”; “I made my way through time” (song); modern vernacular all the way: “I’ve been living with him for twenty years, and he’s been so rude all the way.” Lockn. ; in a broader context, which may contain any syncretistic markers: “The road, the road, there is not much left, We will soon come home”; or not to support them: “I go out alone onto the road, A flinty path lies before me” (Lerm), where the path is not only a synonym for the road, but also the path of life, full of difficulties, hardships, i.e. flinty, thorny.

Entry into the structure of the chronotope is both a consequence and a cause of many symbolic meanings of the concept and lexemes P, D, acting as a semiotic code in the implementation of a number of oppositions that form the mental and verbal picture of the world.

Understanding P, D as a spatial materialization of time made possible such combinations as the life path “life time, life”, the historical path “sequence historical events, historical development" The thread of the road stretching through space, like the thread that the Parks spin, is fate. A clear connection between the idea of fate and the idea of the path is visible in the dialect meaning of the word road “about fate”, in the expressions guiding star, guiding thread. The road-fate - this can be an endless graceless path as a symbol of eternity (the path of Agasphere), thorny path suffering in the name of saving people and understanding eternal values(the way of the cross of Christ), this is a difficult path, full of wanderings, confusion, and struggle in the name of achieving the necessary goals. Much less often, the road is understood as a path to a bright future, a prosperous destiny, inspired by happiness.

In the concept of the path, the opposition life - death clearly reveals itself. The road is a mediator of two spheres, life and death, this world and “that”, one’s own and someone else’s. Both elements of the opposition can be encoded by the images P, D, but to a greater extent - death. This manifests itself in rites and rituals (primarily funeral ones), in the text, and at the lexical level. The semiotic space of life is found in the expressions life path, life road (and even in famous expression, associated with the blockade of Leningrad: the road of life), wide road(s) as a designation of favorable life circumstances. Death is thought of as a transfer to another world, which can be reached by overcoming a certain long and difficult path. This is especially clearly manifested in the texts of funeral lamentations and laments, where there are not only lexemes with the meaning P, D, but also successively replacing names of geographical and natural objects encountered along the way and marking space: “You will go, dear child, You will go along those paths and paths, through forests and dense forests, through greying swamps, along rough streams, you will walk along narrow paths, you will often walk through heather, and how you will meet, my dear, my dear parents.”

The idea of death sounds in the expressions carried out in last way, finish your earthly journey (this is a clichéd phrase included, for example, in the speech of the official manager ritual farewell in the crematorium of St. Petersburg), to the exit “to someone’s death”, Kostr., in lexemes go away “to die”, road “a piece of canvas or a sheet of paper with the words of a prayer, which is placed on the forehead of the deceased or placed in the hands”, conductor “that who reads a prayer over the deceased,” etc.

In folklore, the idea of death, the end, is realized through the image of a sunken road (sink, dial. “cease to exist, disappear, abyss”). A sunken road - broken off in a forest, a swamp, covered with snow, lost while wandering in the forest - is the end of life, love, business. In the songs, the snow covers up “all the paths, all the paths, there is nowhere to go to the little one”; in the epics - “the straight path is fenced in, the path is fenced in, walled up.” A sorcerer or mythical forces can block the way for a person or beast, which is fraught with all sorts of troubles and even death, and only “knowledgeable” people can open the way. [text from the website of the Kizhi Museum-Reserve: http://site]

Finally, the opposition is very relevant, especially at the present time, which has already been mentioned: the opposition “mastered world, ecumene” - “unmastered world, chaos”, connecting with the oppositions “home” - “outside the house”, “one’s own” - “alien”. » The right member of the opposition is more often associated with D, P, which finds various expressions at the level of texts of different genres and structures, in beliefs and rituals, and at the pragmatic level - in the norms of the organization of life. In old Russia, respectable peasants in the villages engaged in highway robbery, and this was not condemned. We find a reflection of this in small forms of folklore: “On the road, an ax is a comrade”; “God forgive the road warrior.” Road rituals are filled with the symbolism of turnover: turning clothes inside out, turning over a collar, throwing them behind one's back - all this is a demonstration of rejection of established norms. In many road rites, the renunciation of God as the maximum embodiment of order, goodness, and norm is obligatory. The road is a place where actions related to evil spirits are performed - divination, fortune telling, etc.; near the roads they bury those who died a death other than their own (this is often done now in relation to those killed in car accidents). In proverbs we find: “The stove wanks, but the path teaches” (because there are many difficulties on the road). At the lexical level: on the road “in vain, in vain.” Reverse relationships are also possible, when the road acts as a zone of stability and order: the road “law, rule, custom” in the text of the sentence when moving to new house: “Your brownie, come with me, I’m dear, you’re on the side (arch.); in proverbs: “I drove along the road, but turned completely.” “Dear 5, but right 10”; by “good, right”, going astray “start leading an immoral life”, going astray (psk.) “the same”, unlucky “not meeting the norms, standards.”

Currently, it is possible to consider the symbolism of the concepts and lexemes P and D together, since in the collective consciousness of the twentieth century they have become very close. According to explanatory dictionaries modern language, the semantic space of both lexemes is almost identical, although the word P has several more values and stable expressions. However, such a rapprochement is a rather late phenomenon. Both concepts and lexemes in the historically foreseeable period have significant differences in their semantic scope and operating conditions. Path is a common Slavic word of Indo-European origin (cf. Lat. pons, pontis, etc.), road is a common Slavic formation from *dьrgati, originally “cleared”. However, a connection with i-e cannot be ruled out. (Old German) Swedish drag “long narrow depression in the soil, lowland, valley”; other - isl. draga "to pull"

The historical development of the semantics of the lexemes P and D, including their rapprochement and repulsion, is very complex and can only be presented in the article in its entirety. general view. However, the following points are quite obvious.

The most important source of symbolization within the concept of the path is biblical text“I am the way, the truth and the life (John 14.6) The text is one of the most sacred places Holy Scripture, because it is an ipse dixit type text, it is repeated in many other texts. In the mouth of the Lord, the word P acquired the symbolic meaning of “a line, a model of righteous behavior, life and worldview.” [text from the website of the Kizhi Museum-Reserve: http://site]

The enrichment of the semantics and freseology of the lexeme P is also associated with biblical parable about the gates of heaven: The gate is wide and the way is wide, leading into the pit... The gate is narrow and the way is narrow, leading into the belly (Matt. U11, 13-14). The opposition: the narrow path (narrow, mournful, regrettable) - “the path of a righteous life” - and the wide path - “the path of a sinful life” - steadily runs through all of our bookishness, right up to the poetry of the 19th century. (See: 4 Robinson).

The semantics of the path as a model of behavior has been stable since the early texts: I will keep my paths, so that I will not sin with my tongue. (CT BEL 350/35)), on its basis many clichéd combinations arose: the virtuous path (Varl., 123), the path of evil (ibid., 134; CT MOL, 197ob/19), the path of rights (CT, TsVT 410/ 9), the right path (CT MOL, 186 rev/45), the righteous path (CT MOL 95 rev/9), the path of salvation (CT SOUL, 345/5), the spiritual path (getting lost) (CT SOUL 344/21) and under.

The ideogram is adjacent to the previous one way of the cross, the thorny path, the path to Golgotha, which is also associated with a certain phraseology of a number of constructions.

The Christian mythologeme of the path, realized through the phraseology of the lexeme P, plays a very large role in expressing the idea of suffering as a means, a path to achieving the main goal of every Christian - eternal salvation, the idea of following and imitating Christ, who went through the path of suffering in the name of saving people and atonement for their sins.

Among the translated texts, but with Old Russian processing, there is a very interesting one, one of early lists which is in the Assumption collection of the 12th-13th centuries: “The legend of our father Agapius, for the sake of leaving families and their homes, and wives, and children, and taking up the cross to follow the gospel” (US). This partly folklorized apocrypha tells of Agapius’ visit to paradise and describes the entire journey to the land of the righteous and back to earth. The idea-symbol of the “Tale” is the earthly life of man as the path to the eternal heavenly life. The artistic and ideological effect in this text is achieved by a complex interweaving of direct and figurative-symbolic meanings of the word P. The text presents almost the entire semantic spectrum of the word; to enhance the emotional impact, the author uses a “game” with the semantics of the word P: “The child (met by Agapius) speech: O Agapie, who is your path and kamo khoshi iti” (path - “direction, route to follow”). Agapius answers that he does not know either the place where he is, or the people, “not my path,” and in his answer the word P has the meaning of a traditional ideological symbol - “life in Christ.” [text from the website of the Kizhi Museum-Reserve: http://site]

The religious-bookish generalization and symbolism of the concept and lexeme P with minor losses and transformations has been preserved to this day: the inscrutable ways of the Lord, the thorny path, the path (road) to Golgotha, the life, historical path, etc. The processes of phraseologization were probably the main the reason for the preservation of features in the declension of the word P. In the last two centuries, there has been a sharp conceptual and semantic convergence of the lexemes P and D, expressed in the “flowing” of the semantic content of the lexeme P into the semantic space of the lexeme D. Song texts, first of all, responded to conceptual and semantic changes. quickly and accurately reflecting changes in collective consciousness. Instead of the established good riddance we find: “Good riddance, good riddance long journey creeps..." ("The Blue Car"), "The soul hurts, and the heart cries, And the earth's path is dusty...", The Milky Road instead of the Milky Way: "Is your path closer than the Milky Road."

Despite the conceptual similarity in modern consciousness, the historical development of the concepts and lexemes P and D has led to the fact that in the Slavic cultural tradition, the symbolism of the path is associated with the Christian-religious view of the world, the symbolism of the road - with pagan worldview and attitude. This also determines the complexity of hypo-hyperonymic relations within the series: path - road - path - path and some. etc., but the presence of a stable path-road complex still forces the lexeme P to be considered a hypernym.

The mythologem of the path in our collective consciousness, in language and speech - huge topic, which has a conceptual, philosophical sound. The historical movement of our country is largely due to the implementation of those aspects of the concept of the path that are most relevant for the collective national consciousness and represent a conglomerate of such components of the concept as the idealization of the sacrificial path in the name of high spiritual values in conjunction with the idea of the eternal path, and roads - spheres of disorder and life's vicissitudes. A rationally constructed, emotionally verified concept of the path, corresponding folk tradition and correcting it - necessary condition successful development of the country; Without a concept of a path forward, it is impossible for Russia to move forward.

// Ryabinin Readings – 1999

Kizhi Museum-Reserve. Petrozavodsk. 2000.

1. The role of the road in the works of Russian classics

1.1 Symbolic function of the road motif

The road is an ancient image-symbol, the spectral sound of which is very wide and diverse. Most often, the image of a road in a work is perceived as the life path of a hero, a people or an entire state. “Life path” in language is a space-time metaphor, which many classics resorted to using in their works: , .

The road motif also symbolizes processes such as movement, search, testing, renewal. In the poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'” the path reflects spiritual movement peasants and all of Russia second half of the 19th century century. And in the poem “I Go Out Alone on the Road,” he resorts to using the road motif to show the acquisition lyrical hero harmony with nature.

IN love lyrics the road symbolizes separation, parting or persecution. A striking example of such an understanding of the image was the poem “Tavrida”.

For the road, it became an incentive for creativity, for the search for the true path of humanity. It symbolizes the hope that such a path will become the fate of his descendants.

The image of a road is a symbol, so each writer and reader can perceive it in their own way, discovering more and more new shades in this multifaceted motif.

1.2 Compositional and semantic roles of the road image

In the memories of friends, of those who are dear and distant, suddenly, imperceptibly, unobtrusively, a road-fate appeared (“We are assigned a different path by strict fate”), pushing people together and separating them.

In love lyrics, the road is separation or pursuit:

Behind her along the slope of the mountains

I walked the unknown road,

And my timid gaze noticed

Traces of her lovely foot.

("Tavrida", 1822)

And the poetic road becomes a symbol of freedom:

You are the king: live alone.

On the road to freedom

Go wherever your free mind takes you...

("To the Poet", 1830)

One of the main themes in Pushkin's lyrics is the theme of the poet and creativity. And here we see the development of the theme through the use of the road motif. “Go along the free path where your free mind takes you,” says Pushkin to his fellow writers. It is the “free road” that should become the path for a true poet.

The road-fate, the free path, the topographical and love roads form a single carnival space in which the feelings and emotions of the lyrical characters move.

The motif of the road occupies a special place not only in Pushkin’s poetry, but also in the novel “Eugene Onegin” it plays a significant role.

Movement is exclusively occupied in Eugene Onegin. great place: the action of the novel begins in St. Petersburg, then the hero goes to the Pskov province, to his uncle’s village. From there the action moves to Moscow, where the heroine goes “to the brides fair” in order to later move with her husband to St. Petersburg. During this time Onegin makes a trip to Moscow - Nizhny Novgorod- Astrakhan - Georgian Military Road - North Caucasian mineral springs - Crimea - Odessa - St. Petersburg. The sense of space, distances, the combination of home and road, home, sustainable and road, mobile life constitute an important part inner world Pushkin's novel. An essential element of spatial sense and artistic time is speed and method of movement.

In St. Petersburg, time flows quickly, this is emphasized by the dynamism of the 1st chapter: « flying in the dust on the postal ones,” “He rushed to Talon...” or:

We better hurry to the ball,

Where to headlong in a Yamsk carriage

My Onegin has already galloped.

After artistic time slows down:

Unfortunately, Larina was dragging herself,

Afraid of expensive runs,

Not on postal ones, on our own,

And our maiden enjoyed

Full of road boredom:

They traveled for seven days.

In relation to the road, Onegin and Tatyana are contrasted. Thus, “Tatyana is afraid of the winter journey,” while Pushkin writes about Onegin:

He was overcome with anxiety

Wanderlust

(A very painful property,

Few voluntary cross).

The novel also raises the social aspect of the motif:

Now our roads are bad

Forgotten bridges are rotting,

There are bugs and fleas at the stations

Minutes don't let me fall asleep...

Thus, based on the analysis of the poet’s poetic text, we can conclude that the motive of the road in the lyrics is quite diverse, the image of the road is found in many of his works, and each time the poet presents it in various aspects. The image of the road helps to show both pictures of life and enhance the coloring of the mood of the lyrical hero.

2.2.2 Lermontov’s theme of loneliness through the prism of the road motif

Lermontov's poetry is inextricably linked with his personality, it is in every sense poetic autobiography. The main features of Lermontov's nature: unusually developed self-awareness, depth moral world, courageous idealism of life's aspirations.

The poem “I go out alone on the road” absorbed the main motives of Lermontov’s lyrics; it is a kind of result in the formation of a picture of the world and the lyrical hero’s awareness of his place in it. Several cross-cutting motives can be clearly traced.

The motive of loneliness. Loneliness is one of the central motifs of the poet: “I am left alone - / Like a dark, empty castle / An insignificant ruler” (1830), “I am alone - there is no joy” (1837), “And there is no one to give a hand / In a moment of spiritual adversity” ( 1840), “I’ve been running around the world alone and without a goal for a long time” (1841). It was proud loneliness among the despised light, leaving no path for active action, embodied in the image of the Demon. It was tragic loneliness, reflected in the image of Pechorin.

The loneliness of the hero in the poem “I go out alone on the road” is a symbol: a person is alone with the world, the rocky road becomes a path of life and a shelter. The lyrical hero goes in search of peace of mind, balance, harmony with nature, which is why the consciousness of loneliness on the road does not have a tragic connotation.

The motive of wandering, the path, understood not only as the restlessness of the romantic hero-exile (“Leaf”, “Clouds”), but the search for the purpose of life, its meaning, which was never discovered, not named by the lyrical hero (“Both boring and sad...” , "Duma").

In the poem “I Go Out Alone on the Road,” the image of the path, “reinforced” by the rhythm of trochaic pentameter, is closely connected with the image of the universe: it seems that space is expanding, this road goes into infinity, and is associated with the idea of eternity.

Lermontov's loneliness, passing through the prism of the road motif, loses its tragic coloring due to the lyrical hero's search for harmony with the universe.

2.2.3 Life is the road of the people in works

An original singer of the people. He started his creative path with the poem “On the Road” (1845), and finished with a poem about the wanderings of seven men in Rus'.

In 1846, the poem “Troika” was written. “Troika” is a prophecy and a warning to a serf girl, who in her youth still dreams of happiness, who for a moment forgot that she is “baptized property” and she is “not entitled to happiness.”

The poem opens with rhetorical questions addressed to the village beauty:

Why are you looking greedily at the road?

Away from cheerful friends?..

And why are you running hastily?

Following the rushing troika?..

The troika of happiness rushes along the road of life. It flies by beautiful girl greedily catching his every movement. While the fate of any Russian peasant woman has long been predetermined from above, and no amount of beauty can change it.

The poet paints a typical picture of her future life, painfully familiar and unchanged. It is hard for the author to realize that time passes, but this strange order of things does not change, so familiar that not only outsiders, but also the participants in the events themselves do not pay attention to it. The serf woman learned to patiently endure life as a heavenly punishment.

The road in the poem robs a person of happiness, which quickly rushes away from the person. A very specific three becomes the author’s metaphor, symbolizing the transience of earthly life. It rushes by so quickly that a person does not have time to realize the meaning of his existence and cannot change anything.

In 1845, he wrote the poem “The Drunkard,” in which he describes the bitter fate of a person sinking “to the bottom.” And again the author resorts to using the road motif, which emphasizes the tragic fate of such a person.

Leaving the destructive path,

I would have found another way

And into another kind of work - refreshing -

I would droop with all my soul.

But the unfortunate peasant is surrounded by injustice, meanness and lies, and therefore there is no other way for him:

But the darkness is black everywhere

Towards the poor...

One is open

The road to the tavern.

The road again acts as a person’s cross, which he is forced to bear throughout his life. One road, no choice of another path - the fate of the unfortunate, powerless peasants.

In the poem “Reflections at the Front Entrance” (1858), talking about peasants, Russian village people who... “wandered for a long time... from some distant provinces” to a St. Petersburg nobleman, the poet speaks of the long-suffering of the people, of their humility. The road takes the peasants on the opposite path, leading them into hopelessness:

...After standing,

The pilgrims untied their wallets,

But the doorman did not let me in, without taking a meager contribution,

And they went, scorched by the sun,

Repeating: “God judge him!”

Throwing up hopeless hands...

The image of the road symbolizes the difficult path of the long-suffering Russian people:

He moans across the fields, along the roads,

He groans in prisons, in prisons,

In the mines, on an iron chain;

... Oh, my heart!

What does your endless groan mean?

Will you wake up full of strength...

Another poem in which the road motif is clearly visible is “Schoolboy”. If in “Troika” and “The Drunkard” there was a downward movement (movement into darkness, an unhappy life), then in “Schoolboy” one can clearly feel the upward movement, and the road itself gives hope for a bright future:

Sky, spruce forest and sand -

Not a fun road...

But there is no hopeless bitterness in these lines, and then the following words follow:

This is the path of many glorious ones.

In the poem "Schoolboy" for the first time a feeling of change appears in spiritual world peasant, which will later be developed in the poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'.”

The poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'” is based on a story about peasant Russia, deceived by government reform (Abolition of serfdom, 1861). The beginning of the poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'” with the significant names of the province, district, volost, villages attracts the reader’s attention to the plight of the people. Obviously, the bitter fate of the temporarily obliged men who met on the public road turns out to be the initial cause of the dispute about happiness. After arguing, seven men set off on a long journey across Russia in search of truth and happiness. The Nekrasov peasants who set off on their journey are not traditional pilgrims - they are a symbol of a post-reform people's Russia that has set off, thirsty for change:

The theme and image of the road-path are in one way or another connected with various characters, groups of characters, and with the collective hero of the work. In the world of the poem, such concepts and images as the path - the crowd - the people - the old and new worlds - labor - the world - were illuminated and, as it were, linked together. The expansion of the life impressions of male debaters, the growth of their consciousness, a change in views on happiness, the deepening of moral concepts, social insight - all this is also connected with the motive of the road.

The people in Nekrasov's poem are a complex, multifaceted world. The poet connects the fate of the people with the union of the peasantry and the intelligentsia, which walks a close, honest path “for the bypassed, for the oppressed.” Only the joint efforts of revolutionaries and the people who are “learning to be citizens” can, according to Nekrasov, lead the peasantry onto the broad road of freedom and happiness. In the meantime, the poet shows the Russian people on the way to a “feast for the whole world.” N. A. Nekrasov saw in the people a force capable of achieving great things:

The army rises -

Countless!

The strength in her will affect

Indestructible!

Faith in the “broad, clear road” of the Russian people is the poet’s main faith:

…Russian people…

He will endure whatever the Lord sends!

Will bear everything - and a wide, clear

He will pave the way for himself with his chest.

The thought of the spiritual awakening of the people, especially the peasantry, haunts the poet and penetrates all the chapters of his immortal work.

The image of the road that permeates the poet’s works acquires an additional, conditional, metaphorical meaning from Nekrasov: it enhances the feeling of changes in the spiritual world of the peasant. The idea runs through all the poet’s work: life is a road and a person is constantly on the move.

2.2.4 The road - human life and the path of human development in the poem “Dead Souls”

The image of the road appears from the first lines of the poem “Dead Souls”. We can say that he stands at its beginning. “A rather beautiful small spring britzka drove into the gates of the hotel in the provincial town of NN...” The poem ends with the image of a road: “Rus', where are you rushing, give me the answer?.. Everything that is on earth flies past, and, looking askance, other peoples and states step aside and give it way.”

But these are completely different roads. At the beginning of the poem, this is the road of one person, a specific character - Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov. In the end, this is the road of the whole state, Russia, and even more, the road of all humanity; a metaphorical, allegorical image appears before us, personifying the gradual course of all history.

These two values are like two extreme milestones. Between them there are many other meanings: both direct and metaphorical, forming a single, complex image Gogol road.

The transition from one meaning to another - concrete to metaphorical - most often occurs unnoticed. Chichikov leaves the city of NN. “And again on both sides of the pillar path they went to write miles again, station guards, wells, carts, gray villages with samovars, women and a lively bearded owner...” etc. Then follows the author’s famous appeal to Rus': “Rus! Rus! I see you, from my wonderful, beautiful distance I see you..."

The transition from specific to general is smooth, almost imperceptible. The road along which Chichikov travels, endlessly lengthening, gives rise to the thought of all of Rus'. Further, this monologue is interrupted by another shot: “... And a mighty space threateningly embraces me, with terrible force reflected in my depths; My eyes lit up with unnatural power: oh! what a sparkling, wonderful, unknown distance to the earth! Rus!

Hold it, hold it, you fool!” Chichikov shouted to Selifan.

Here I am with a broadsword! - shouted a courier with a mustache as long as he was galloping towards the meeting. - Don’t you see, damn your soul: it’s a government carriage! - and, like a ghost, the troika disappeared with thunder and dust.

How strange, and alluring, and carrying, and wonderful is the word: road! And How

The road itself is wonderful: a clear day, autumn leaves, cold air...

We’ll put on our travel overcoat tighter, we’ll put a hat on our ears, and we’ll snuggle closer and more comfortably into the corner!”

The famous Russian scientist A. Potebnya found this place “brilliant”. Indeed, the sharpness of the transition is brought to its highest point, one plan is “pushed” into another: Chichikov’s rude abuse bursts into the author’s inspired speech. But then, also unexpectedly, this picture gives way to another: as if both the hero and his chaise were just a vision of M. It should be noted that, having changed the type of story - prosaic, with extraneous remarks, to inspired, sublimely poetic - N. Gogol did not change his character this time central image- image of the road. It did not become metaphorical - before us is one of the countless roads of the Russian expanses.

The change of direct and metaphorical images of the road enriches the meaning of the poem. The dual nature of this change is also important: gradual, “prepared”, and sharp, sudden. The gradual transition of one image to another recalls the generality of the events described: Chichikov’s path is the life path of many people; individual Russian highways and cities form a colossal and wonderful image of the homeland.

Sharpness speaks of the sharp “contrast between an inspired dream and a sobering reality.”

Now let’s talk in more detail about the metaphorical meanings of the image of the road. First, about the one that is equivalent to a person’s life path.

In fact, this is one of the oldest and most widespread images. One can endlessly give poetic examples in which a person’s life is interpreted as the passage of a path, a road. in “Dead Souls” also develops metaphorical image roads as “human life”. But at the same time it finds its own original twist to the image.

Beginning of Chapter VΙ. The narrator recalls how in his youth he was excited about encountering any unfamiliar place. “Now I indifferently approach any unfamiliar village and indifferently look at its vulgar appearance; It’s unpleasant to my chilled gaze, it’s not funny to me, and what would have awakened in previous years a lively movement in the face, laughter and silent speech, now slides past, and my motionless lips keep an indifferent silence. O my youth! oh my freshness!

A contrast arises between the end and the beginning, “before” and “now”. On the road of life, something very important and significant is lost: freshness of sensations, spontaneity of perception. In this episode, the change of a person on the path of life is brought to the fore, which is directly related to the internal theme of the chapter (VΙ chapter about Plyushkin, about the amazing changes that he had to endure). Having described these metamorphoses, Gogol returns to the image of the road: “Take it with you on the road, leaving teenage years into stern, embittering courage, take away all human movements, do not leave them on the road: do not raise them later!”

But the road is not only “a person’s life,” but also a creative process, a call to tireless writing: “And for a long time yet, the wonderful power has determined for me to walk hand in hand with my strange heroes, to survey the whole enormously rushing life, to survey it through the laughter visible to the world and invisible, unknown to him tears!... On the road! on the road! away the wrinkle that has appeared on the forehead and the stern gloom of the face! Let’s suddenly plunge into life with all its silent chatter and bells and see what Chichikov is doing.”

Gogol highlights other meanings in the word road, for example, a way to resolve some difficulty, to get out of difficult circumstances: “And how many times already induced by the meaning descending from heaven, they knew how to recoil and stray to the side, they knew how to find themselves again in impenetrable backwaters in broad daylight, they knew how to again throw a blind fog into each other’s eyes and, trailing after the swamp lights, they knew how to - to finally get to the abyss, and then ask each other in horror: where is the exit, where is the road? The expression of the word road is strengthened here with the help of antithesis. Exit , the road is opposed to a swamp, an abyss .

And here is an example of the use of this symbol in the author’s discussion about the paths of human development: “What crooked, deaf, narrow, impassable roads that lead far to the side have been chosen by humanity, striving to achieve eternal truth...”. And again the same expansion technique visual possibilities words - the opposition of a straight, rough path, which is “wider than all other paths... illuminated by the sun,” with a curved road leading to the side.

In concluding the first volume " Dead souls» lyrical digression the author talks about the ways of development of Russia, about its future:

“Isn’t it so for you, Rus', that you are rushing along like a brisk, unstoppable troika? The road beneath you smokes, the bridges rattle, everything lags behind and remains behind... everything that is on the earth flies past, and, looking sideways, other peoples and states step aside and give way to it.” In this case, the expressiveness of the word is enhanced by contrasting it different meanings: the path of development of Russia and a place for passage, passage.

The image of the people is metamorphically connected with the image of the road.

“What does this vast expanse prophesy? Is it here, in you, that a boundless thought will not be born, when you yourself are without end? Shouldn't a hero be here when there is room for him to turn around and walk?

Eh, three! bird three, who invented you? know u spirited people you could only have been born in that land that doesn’t like to joke, but was scattered across half the world, and go count the miles until it hits you in the eyes... the Yaroslavl quickly equipped and gathered you alive, with just an ax and a chisel efficient man. The driver is not wearing German boots: he has a beard and mittens, and sits on God knows what; but he stood up, swung, and began to sing - the horses were like a whirlwind, the spokes in the wheels mixed into one smooth circle, only the road trembled, and the stopped pedestrian screamed in fright! and there she rushed, rushed, rushed!..”

Through the connection with the image of the “troika bird”, the theme of the people at the end of the first volume leads the reader to the theme of the future of Russia: “. . . and rushes, all inspired by God!... Rus', where are you rushing, give me the answer? Doesn't give an answer. The bell rings with a wonderful ringing... and, looking askance, other peoples and states step aside and give way to it.”

The language of the stylistic diversity of the image of the road in the poem “Dead Souls” corresponds to a sublime task: a high style of speech and means characteristic of poetic language are used here. Here are some of them:

Hyperbole: “Shouldn’t a hero be here when there is a place for him to turn around and walk?”

Poetic syntax:

a) rhetorical questions: “And what Russian doesn’t like driving fast?”, “But what incomprehensible, secret force attracts you?”

b) exclamations: “Oh, horses, horses, what kind of horses!”

c) appeals: “Rus, where are you rushing?”

Everything is in motion, in continuous development, and the motif of the road also develops. In the twentieth century, it was picked up by such poets as A. Tvardovsky, A. Blok, A. Prokofiev, S. Yesenin, A. Akhmatova. Each of them saw in it more and more unique shades of sound. The formation of the image of the road continues in modern literature.

Gennady Artamonov, a Kurgan poet, continues to develop the classic idea of the road as a life path:

Today there is silence in our class,

Let's sit down before the long journey,

This is where it starts

He goes into life from the school threshold.

"Goodbye, school!"

Nikolai Balashenko creates a vivid poem “Autumn on Tobol”, in which the motive of the road is clearly visible:

I walk along the path along Tobol,

There is an incomprehensible sadness in my soul.

Cobwebs float weightlessly

On your autumn unknown journey.

The subtle interweaving of the topographic component (the path along the Tobol) and the “life path” of the web gives rise to the idea of unbreakable connection between life and the Motherland, past and future.

The road is like life. This idea became fundamental in Valery Egorov’s poem “Crane”:

We choose our own stars,

We follow their light along the paths,

We lose and break ourselves along the way,

But still we go, we go, we go...

Movement is the meaning of the universe!

And meetings are miles along the way...

The same meaning is embedded in the poem “Duma”, in which the motif of the road sounds half-hints:

Crossroads, paths, stops,

In modern literature, the image of the road has acquired a new original meaning; poets are increasingly resorting to using paths, which may be associated with complex realities modern life. The authors continue to comprehend human life as a path that must be passed.

3. “Enchanted Wanderers” and “Inspired Vagabonds”

3.1 “Unhappy Wanderers” by Pushkin

Endless roads, and on these roads there are people, eternal vagabonds and wanderers. Russian character and mentality encourage an endless search for truth, justice and happiness. This idea is confirmed in such classic works as “The Gypsies”, “Eugene Onegin”, “The Sealed Angel”, “The Cathedral People”, “The Enchanted Wanderer”.

You can meet the unfortunate wanderers on the pages of the poem “Gypsies”. “Gypsies contains a strong, deep and completely Russian thought. “Nowhere can one find such independence of suffering and such depth of self-awareness inherent in the wandering element of the Russian spirit,” he said at a meeting of the society of amateurs Russian literature. And indeed, in Aleko Pushkin noted the type of unfortunate wanderer on native land who cannot find a place for himself in life.

Aleko is disappointed in social life, dissatisfied with it. He is a “renegade of the world”, it seems to him that he will find happiness in a simple patriarchal environment, among free people, not subject to any laws. Aleko's mood is an echo of romantic dissatisfaction with reality. The poet sympathizes with the exiled hero, at the same time Aleko is subjected to critical reflection: his love story and the murder of a gypsy characterize Aleko as a selfish person. He was looking for freedom from chains, and he was trying to put them on another person. “You only want freedom for yourself,” as folk wisdom the words of the old gypsy sound.

Such a human type as described in Aleko does not disappear anywhere; only the direction of the personality’s escape is transformed. The former wanderers, in the opinion, went after the gypsies, like Aleko, and his contemporary ones went into the revolution, into socialism. “They sincerely believe that they will achieve their goal and happiness, not only personal, but also world-wide,” argued Fyodor Mikhailovich, “the Russian wanderer needs world-wide happiness, he will not be satisfied with anything less.” the first to mark our national essence.

In Eugene Onegin, many things resemble images Caucasian prisoner and Aleko. Like them, he is not satisfied with life, he is tired of it, his feelings have cooled. But nevertheless, Onegin is a socio-historical, realistic type, embodying the appearance of a generation whose life is determined by certain personal and social circumstances, a certain social environment of the Decembrist era. Evgeny Onegin is a child of his century, he is the successor of Chatsky. He, like Chatsky, is “condemned” to “wandering”, condemned to “search around the world, where there is a corner for the offended feeling.” His chilled mind questions everything, nothing captivates him. Onegin is a freedom-loving person. He has “direct nobility of soul”, he was able to love Lensky with all his heart, but nothing could seduce him with Tatyana’s naive simplicity and charm. He is characterized by both skepticism and disappointment; the traits of a “superfluous person” are noticeable in him. These are the main character traits of Eugene Onegin, which make him “rush around Russia like a wanderer who cannot find a place for himself.”

But neither Chatsky, nor Onegin, nor Aleko can be called genuine “wandering sufferers”, the true image of which will be created.

3.2 “Wanderers-sufferers” - the righteous

The “Enchanted Wanderer” is a type of “Russian wanderer” (in the words of Dostoevsky). Of course, Flyagin has nothing in common with the superfluous people of the nobility, but he, too, is searching and cannot find himself. “The Enchanted Wanderer” has a real prototype - the great explorer and sailor Afanasy Nikitin, who in a foreign land “suffered for faith”, for his homeland. So Leskov’s hero, a man of boundless Russian prowess and great simplicity, cares most about his native land. Flyagin cannot live for himself, he sincerely believes that life should be given for something greater, common, and not for the selfish salvation of the soul: “I really want to die for the people.”

The main character feels some kind of predetermination of everything that happens to him. His life is built according to the well-known Christian canon, contained in the prayer “For those sailing and traveling, those suffering in illness and captivity.” By way of life, Flyagin is a wanderer, fugitive, persecuted, not attached to anything earthly in this life; he went through cruel captivity and terrible Russian ailments and, freed from “anger and need,” turned his life to serving God.

The appearance of the hero resembles the Russian hero Ilya Muromets, and Flyagin’s irrepressible vitality, which requires an outlet, prompts the reader to compare with Svyatogor. He, just like the heroes, brings kindness to the world. Thus, in the image of Flyagin there is a development folklore traditions epic

Flyagin’s whole life was spent on the road, his life’s path is the path to faith, to that worldview and state of mind in which we see the hero in the last pages of the story: “I really want to die for the people.” In the very wandering of Leskov’s hero there is deepest meaning; It is on the roads of life that the “enchanted wanderer” comes into contact with other people and opens up new life horizons. His journey does not begin at birth, turning point Flyagin's destiny became love for the gypsy Grushenka. This bright feeling became the impetus for the moral growth of the hero. It should be noted: Flyagin’s path is not over yet; there is an endless number of roads ahead of him.

Flyagin - eternal wanderer. The reader meets him on the way and parts with him on the eve of new roads. The story ends on a note of quest, and the narrator solemnly pays tribute to the spontaneity of eccentrics: “his messages remain until the time of hiding his destinies from the smart and reasonable and only sometimes revealing them to babies.”

Comparing Onegin and Flyagin with each other, one can come to the conclusion that these heroes are opposites, representing vivid examples of two types of wanderers. Flyagin sets out on the journey of life to grow up and strengthen his soul, while Onegin runs away from himself, from his feelings, hiding behind a mask of indifference. But they are united by the road they follow throughout their lives, a road that transforms the souls and destinies of people.

Conclusion.

The road is an image used by all generations of writers. The motif originated in Russian folklore, then it continued its development in works of literature of the 15th century, was picked up by poets and writers of the 19th century, and is not forgotten now.

The path motif can perform both a compositional (plot-forming) function and a symbolic one. Most often, the image of a road is associated with the life path of a hero, a people or an entire state. Many poets and writers resorted to the use of this space-time metaphor: in the poems “To Comrades” and “October 19”, in the immortal poem “Dead Souls”, in “Who Lives Well in Rus'”, in “The Enchanted Wanderer”, V. Egorov and G. Artamonov.

In poetry, the variety of roads forms a single “carnival space”, where one can meet Prince Oleg and his retinue, a traveler, and the Virgin Mary. The poetic road presented in the poem “To the Poet” has become a symbol of free creativity. The motif also occupies an exceptionally large place in the novel “Eugene Onegin”.

In his work, the road motif symbolizes the lyrical hero’s finding harmony with nature and with himself. And the road reflects the spiritual movement of the peasants, search, testing, renewal. The road meant a lot to him too.

Thus, the philosophical sound of the road motif helps to reveal ideological content works.

The road is unthinkable without travelers, for whom it becomes the meaning of life, an incentive for personal development.

So, the road is an artistic image and a plot-forming component.

The road is a source of change, life and help in difficult times.

The road is both the ability to create, and the ability to understand the true path of man and all humanity, and the hope that contemporaries will be able to find such a path.

Vyacheslav way

Evgeniy Which one exactly? Russian to demolished suspension

Pavel The road symbolizes Life.

The road symbolizes the path, quests, aspirations... The road is an incomplete...

Ivan The road must lead to the Temple, otherwise it is not needed at all.

Gennady dream and aspirations

This road is what we need, anyone who crosses the border sees this miracle of engineering, probably this road has made...

remember the pictures of the song in which the symbols of the sun are embodied, the road of the tree | Topic author: Ilya

Anatoly paintings or songs?

Peter The SUN gives light and warmth, is a symbol of life. A TREE grows, and when it loses its foliage, it gains it again and again, i.e., as if Nikita dies and is resurrected. THE ROAD is an image-symbol that has special meaning for the Russian person. THE PATH OF LIFE is a kind of road that everyone must travel. The road has long captivated and attracted Russian people with new opportunities, fresh impressions, and tempting changes. The image of a road in art. Let's look at it in detail. The image of the road has become widespread in art, and especially in folklore. Question: what does the word folklore mean? folk wisdom. Many plots of folk tales are associated with the passage of a path-road in a straight line and figuratively. Give examples? “How the Fool Ivanushka Followed a Miracle”, “Kolobok”, “Geese and Swans”, etc. Domestic art knows a lot of musical, pictorial, and graphic works that are dedicated to the image of the road. It is enough to name the following names: composers: M. I. Glinka, P. I. Tchaikovsky, S. Taneyev, S. Rachmaninov, G. Sviridov; artists: Ivan Bilibin Artyom, Victor Mikh. Vasnetsov Vladimir, Isaac Ilyich Levitan Alexey, Nikolai Konstant. Roerich Gregory, Alexey Kondrat. Savrasov Viktor, Ivan Iv. Shishkin Dima.

Sergey itself)

INSTRUCTIONS ABOUT THE STANDARDS AND PROCEDURE FOR WITHDRAWAL...

The railroad right-of-way includes lands occupied by earthen... right-of-way on haul routes with an embankment height and excavation depth of up to 1 m, ...