Russian traditional costume. Description of the project "Russian folk costume"

Introduction.

1 presenter: “ Hello, this year we often heard the name “Russian” in lessons. folk costume ", 2nd presenter: "... we wanted to know how the Russian people got their costume, how long ago it happened and what it was sewn from, made of, what parts it consisted of and what it was decorated with.1 presenter : “We addressed these questions to the teacher and our parents. They opened before us interesting books, dictionaries, albums with illustrations of paintings famous artists, videos about the origin of Russian folk costume."

2 presenter : “From the information collected, with the help of our manager, we created a project, which we present to you today.”

Russian folk costume

Folk costume is an invaluable cultural heritage of the people, accumulated over centuries. Clothes that have undergone development long haul, is closely connected with the history of the Russian people.

This bright part culture and unification various types creativity, the use of materials and decorations characteristic of Russian clothing in the past.

"From the depths of centuries"

How do we know how our people dressed up a thousand years ago? distant ancestors What did they wear in winter and summer, on holidays and ordinary days? Of course, many questions are answered primarily by archeology and, of course, the work of restorers.

What is archeology? This is a science that studies the history of society and people’s activities based on the surviving material remains.

Archaeologists find rich, comfortable and beautiful outfits underground.

They and their images have been preserved to this day with the help of restorers.

And restorers are people who restore the original appearance of destroyed or damaged works ancient art(paintings, icons, clothes, jewelry, household items...).

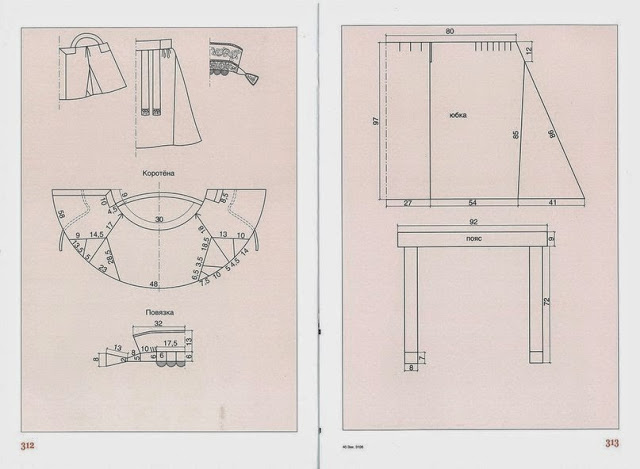

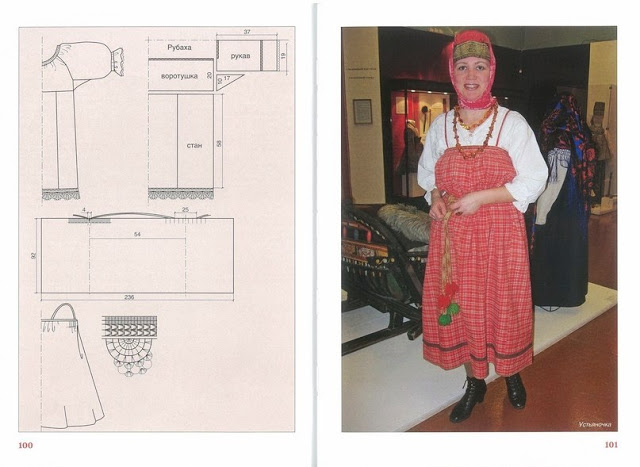

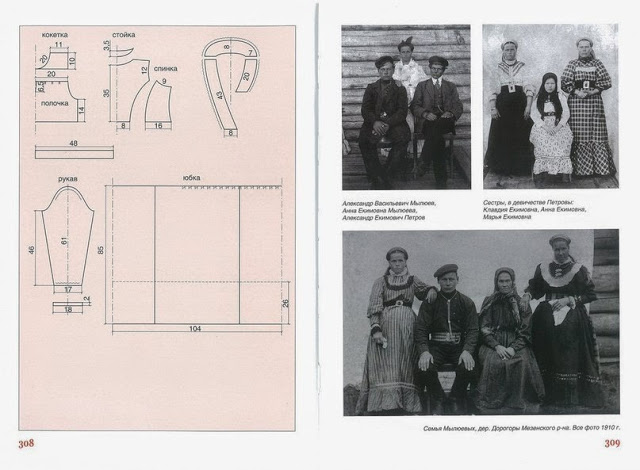

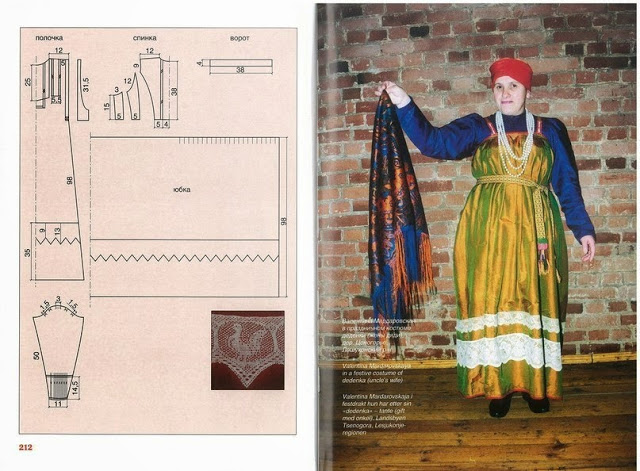

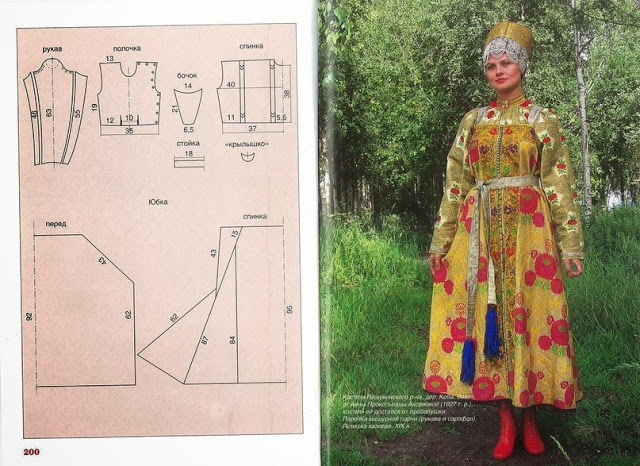

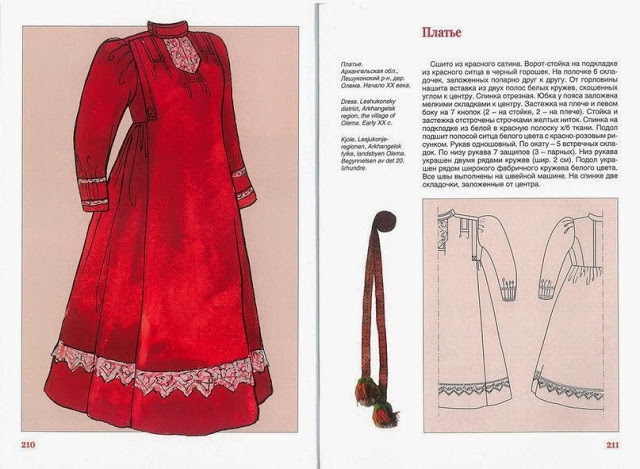

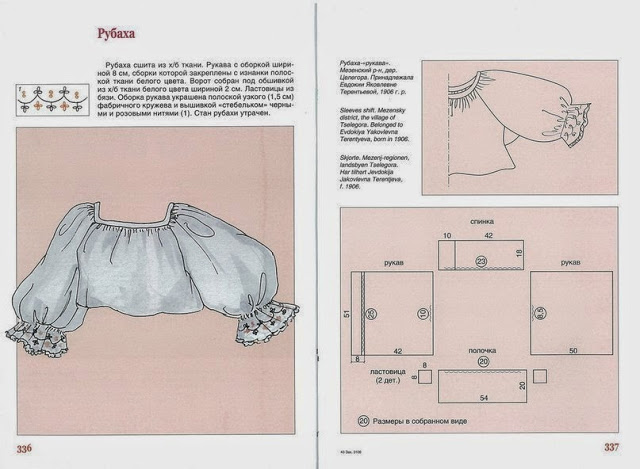

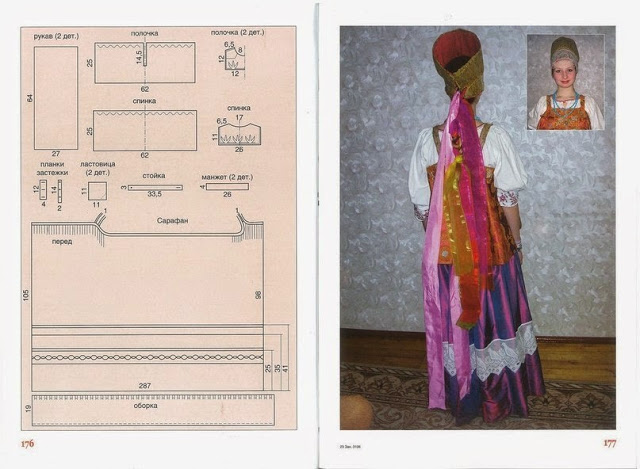

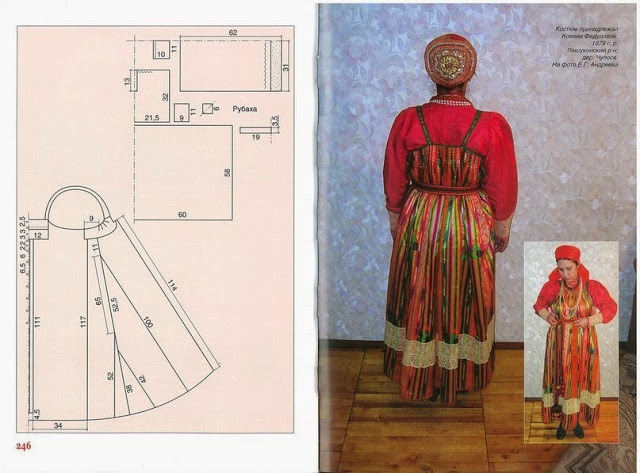

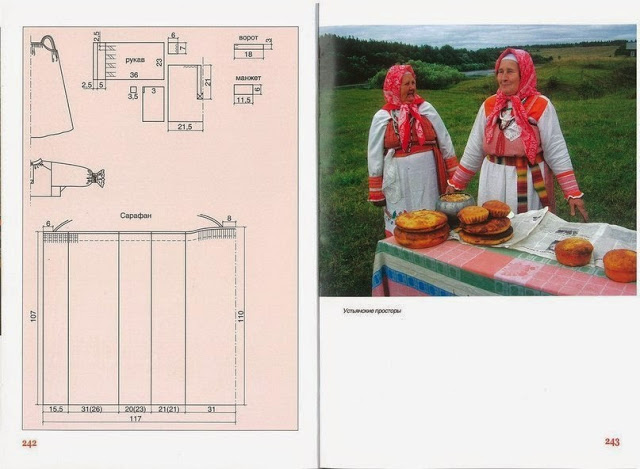

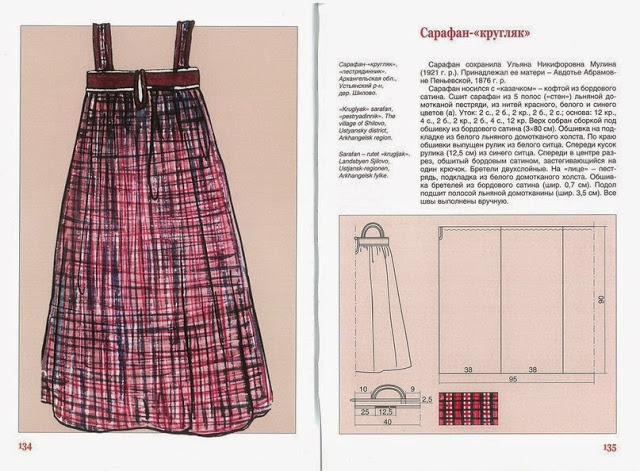

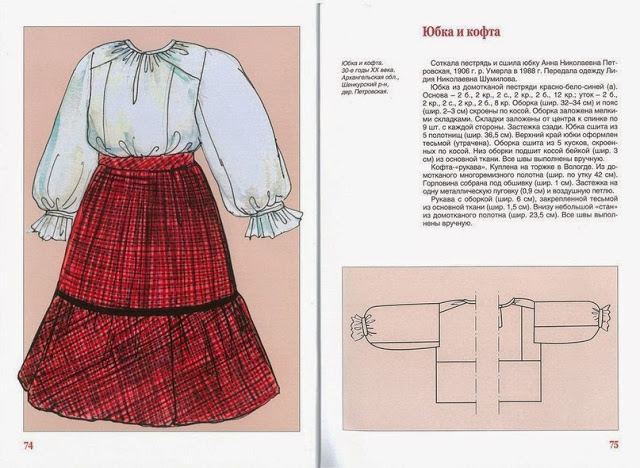

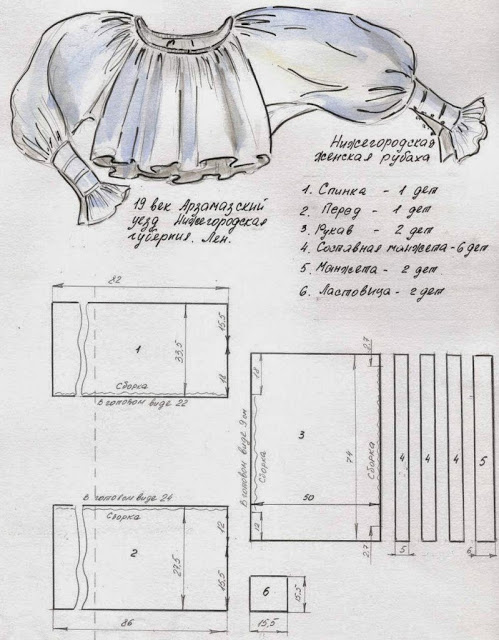

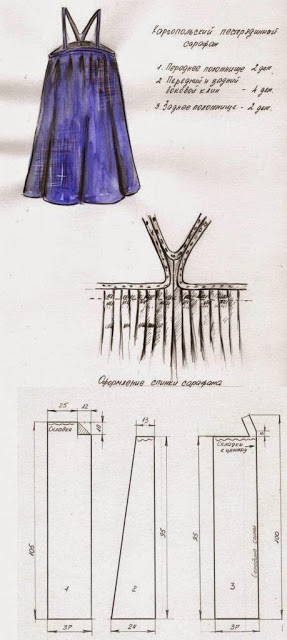

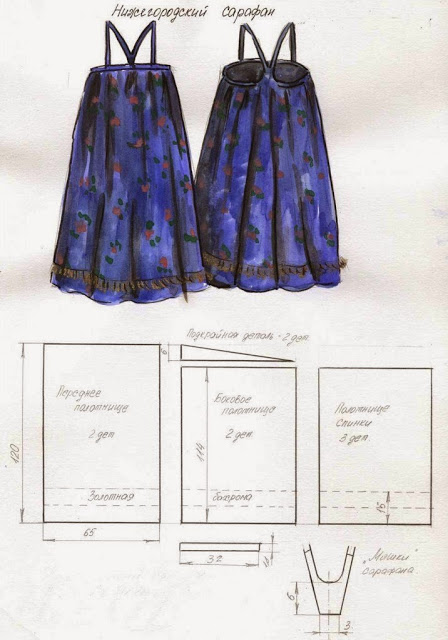

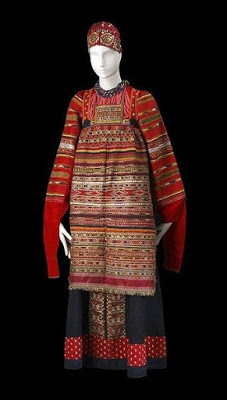

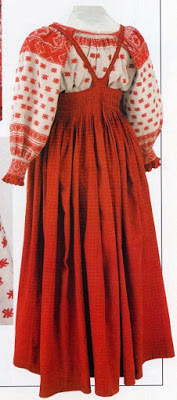

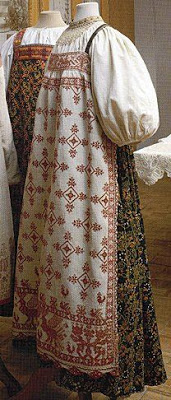

Sundress

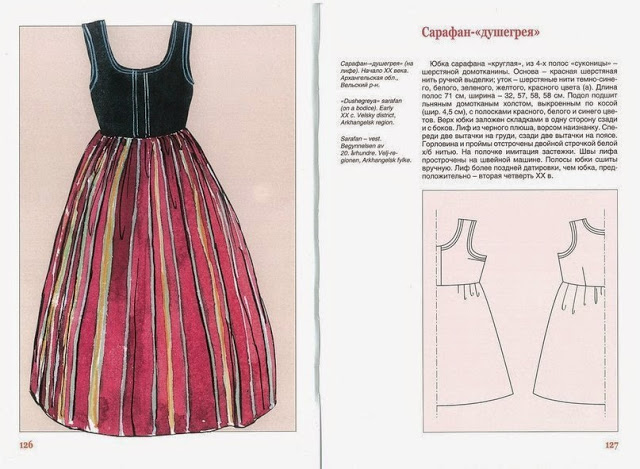

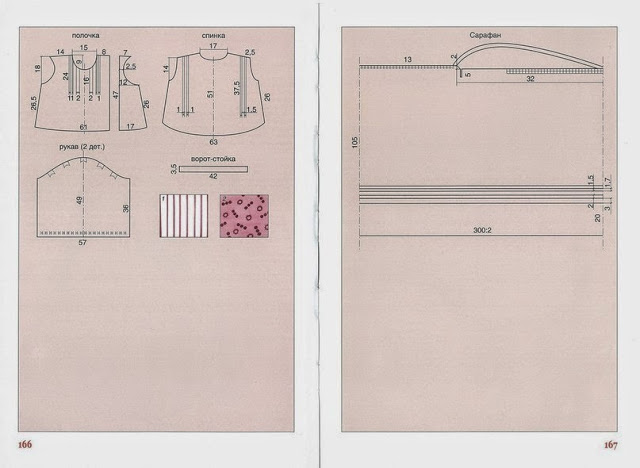

The national costume of Russian women was the sundress. Until the beginning of the 18th century, representatives of the upper classes also wore it, and in late time They were preserved mainly only in rural areas. Presumably the word "sarafan" comes from the Iranian "sarapa" - dressed from head to toe.

Festive sundresses were made from more expensive fabrics, while everyday sundresses were made mainly from homespun.

Less common, which was a unique version of a round sundress, was a sundress with a bodice, consisting of two parts.

In addition, in some regions a high skirt (under the chest) without straps was also called a sundress.

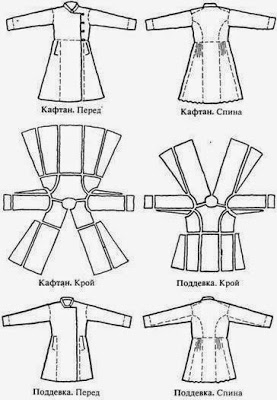

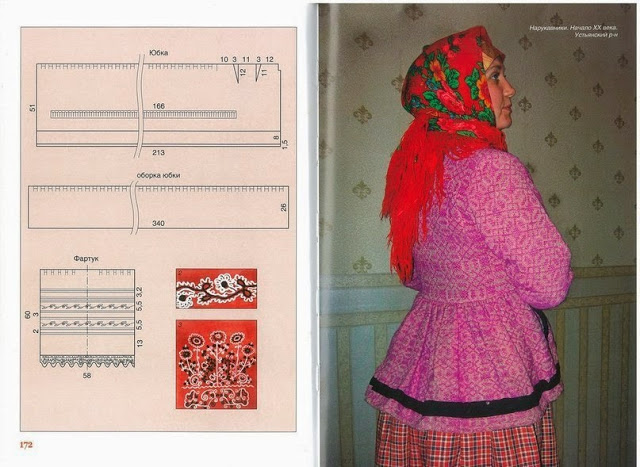

Outerwear

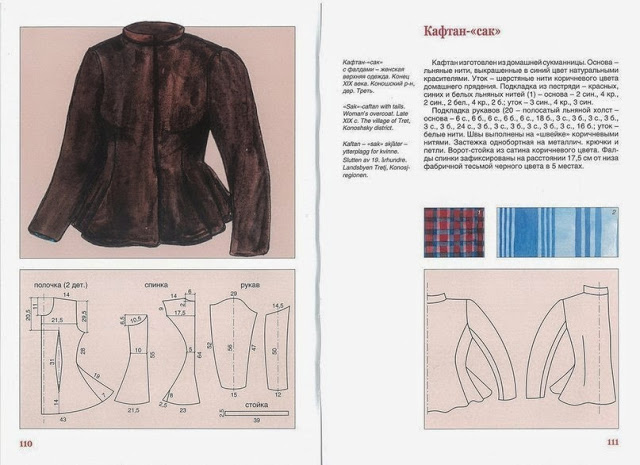

In winter and summer, men and women wore single-breasted caftans, women had a clasp on the right side, and men had a clasp on the left, they were called ponitkas, shaburs, Siberians, armyaks ..... They had a cut-off waist, at first wide pleats - plastic, later fluffy gathers. .

Travel clothes were sheepskin coats and zipuns.

Russian peasants also had clothes specially designed for work and household chores. Men hunters and fishermen wore luzans.

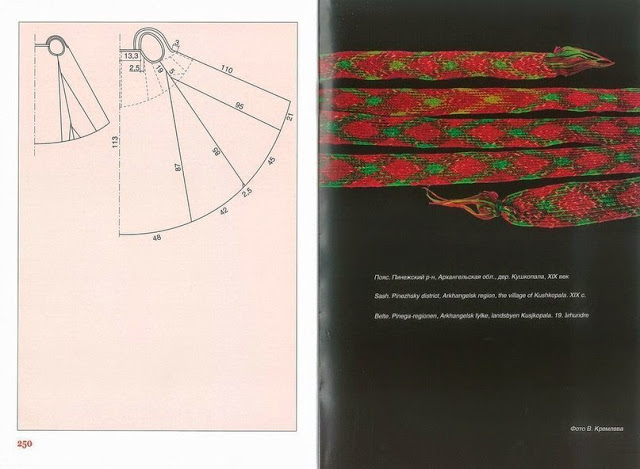

Belts

A must-have detail for men's and women's suit there were belts, in the northern regions they were also called girdles. “Women, as a rule, wore a woven or fabric belt, and men wore a leather one, and their outer clothing was tied up with wide sashes.

Hats

Russian headdresses varied in shape. The main material was fur.

Women's headdresses were more varied, but all their diversity comes down to several types: a scarf, a hat, a cap and a maiden's crown.

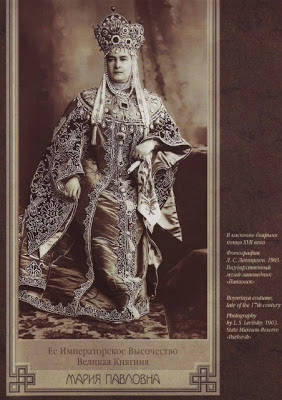

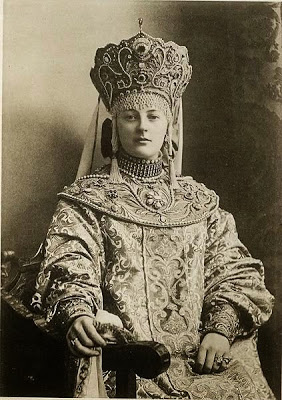

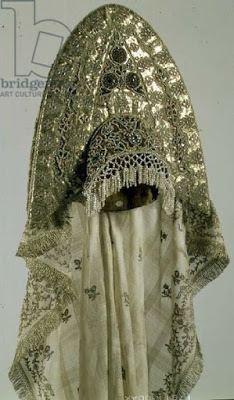

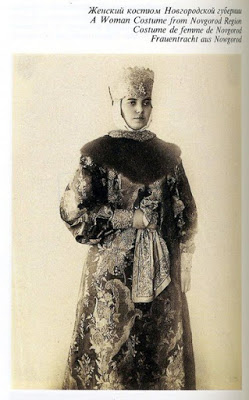

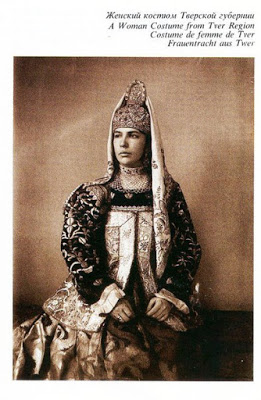

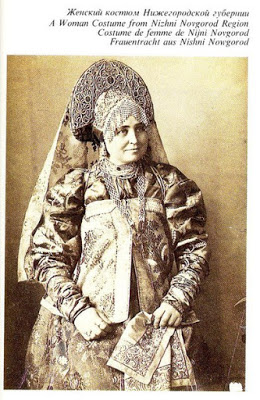

Married women wore their hair around their heads, and their headdress was a kokoshnik, which was decorated with gold embroidery, pearls or beads. Married women always wore a scarf or shawl over small headdresses that hid their hair.

Shoes

Animal skins, tanned leather, less often fur, tree bark, and hemp rope were used as materials for making shoes. The oldest among Russians should be considered leather shoes, which were not sewn, but wrinkled - they tied a piece of leather with ropes so that folds formed on the sides and tied it to the foot with a long rope. These shoes were called pistons.

The most common shoes can be considered bast shoes. These are shoes woven from bast wood, like sandals. In rainy weather, a small plank was tied to the bast shoes - the sole. With bast shoes and other low shoes they wore onuchi - long narrow strips of wool fabric. Long winter evenings the head of the family wove bast shoes for the whole family, using a tool called a kochedyk. On average, one pair of bast shoes wore out in three to four days.

Conclusion

The folk costume, its variety of colors and embroidery still makes us admire. They infect us with a mood of festivity and fun. Folk craftsmen they know how to transform an ordinary thing into a work of art.

Collections of Russian folk costume stored in museums reveal to us beautiful folk art, the rich imagination of Russian people, their subtle artistic taste And high craftsmanship. Perhaps no country in the world, no people has such a wealth of traditions in the field of national folk art like Russia.

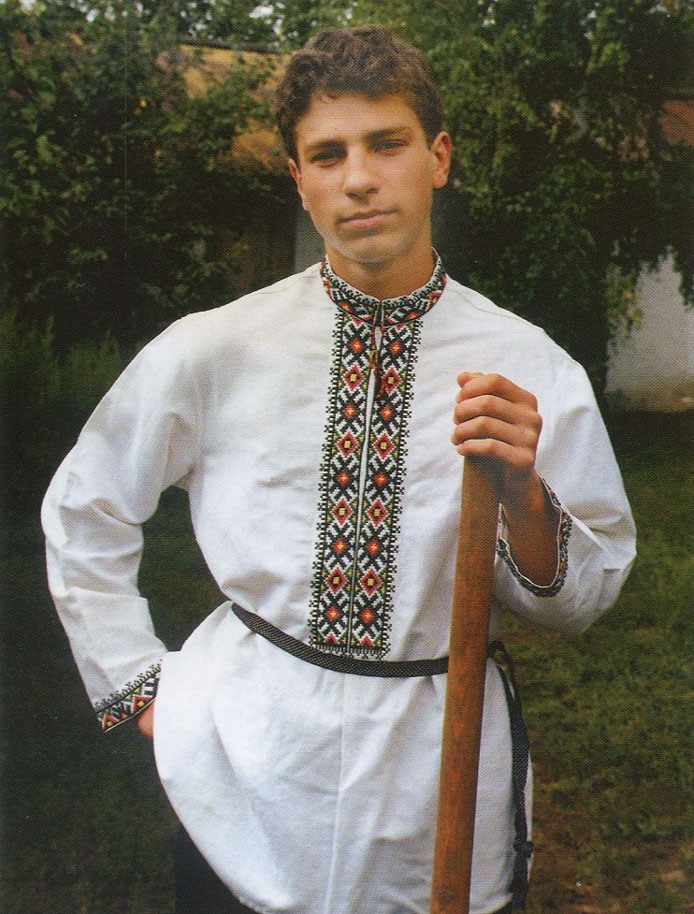

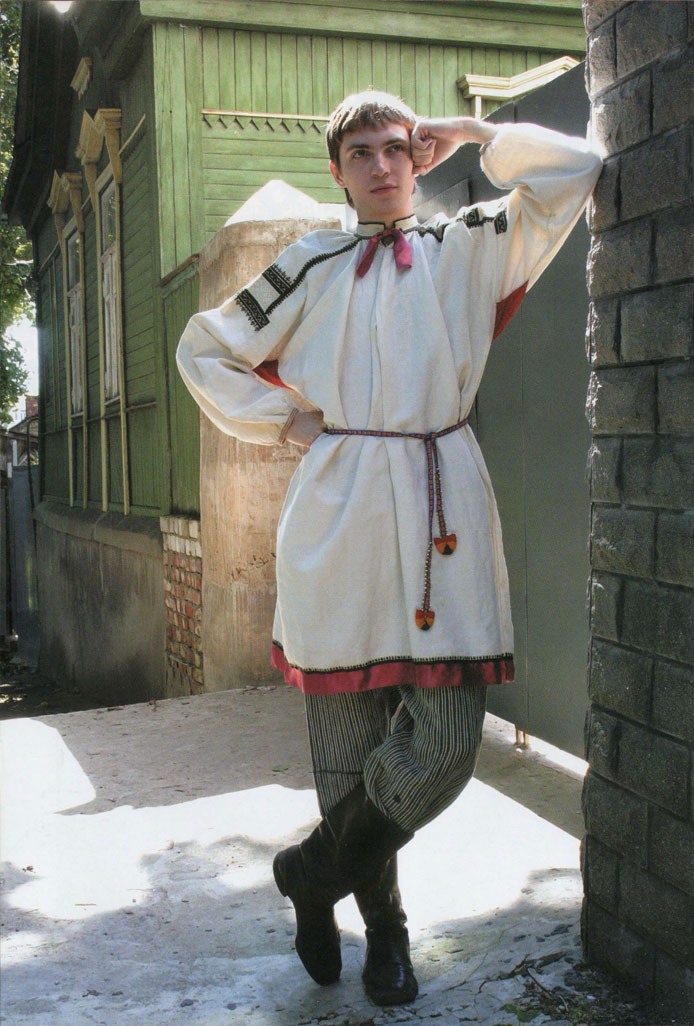

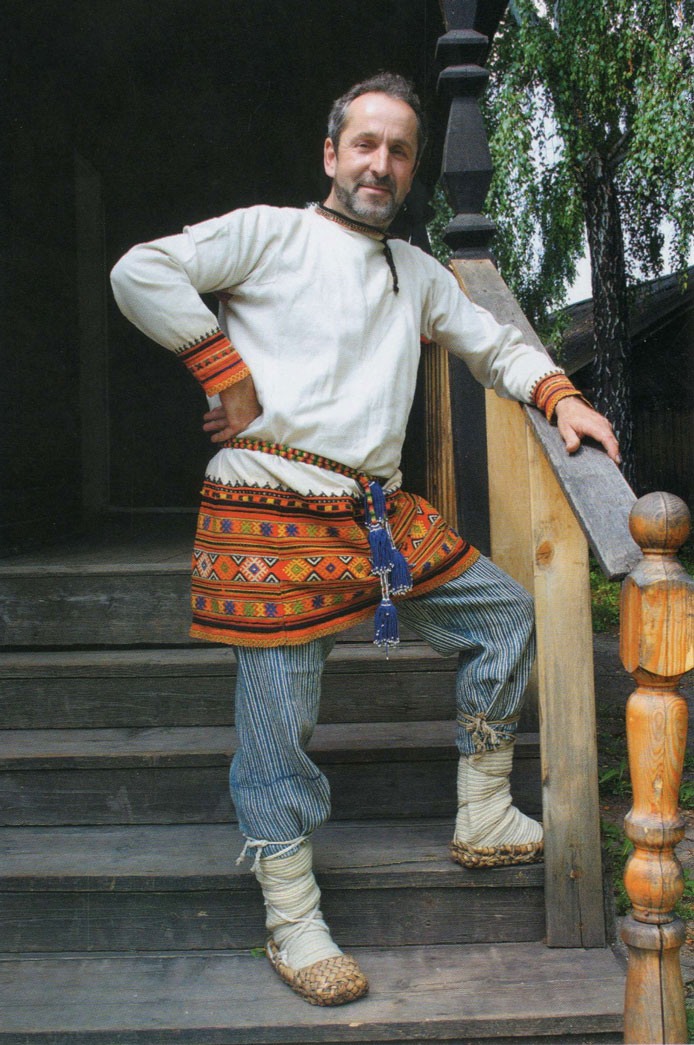

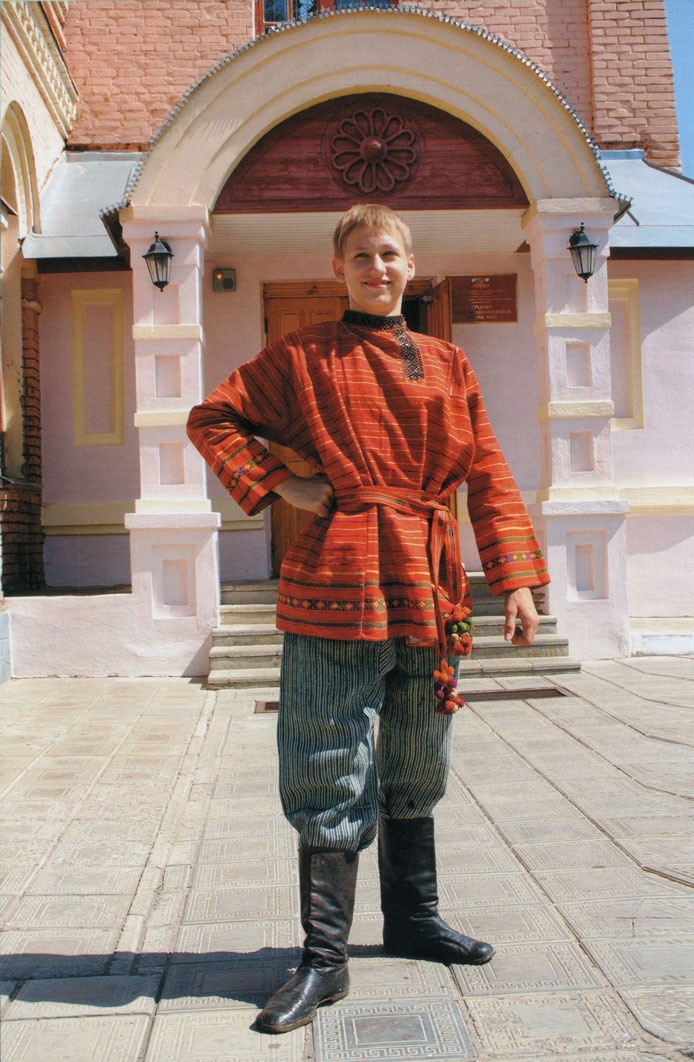

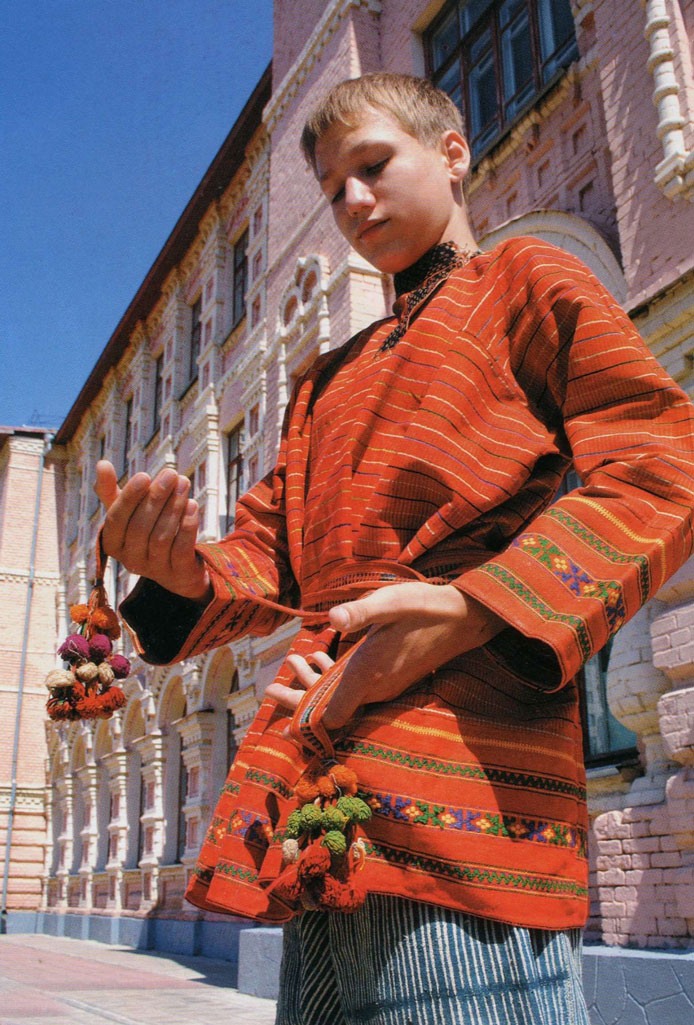

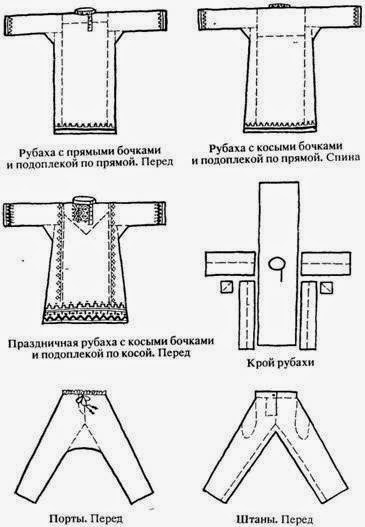

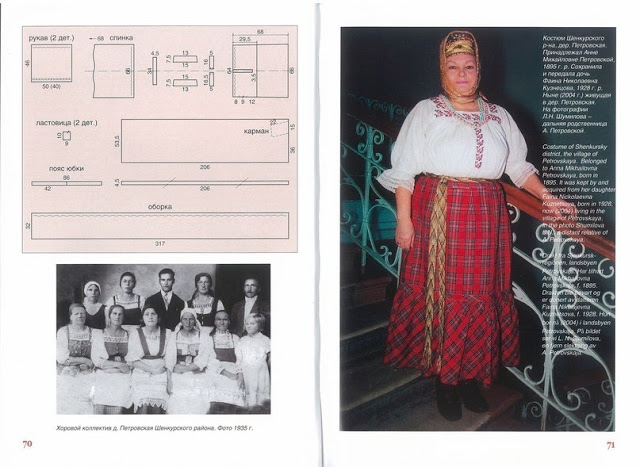

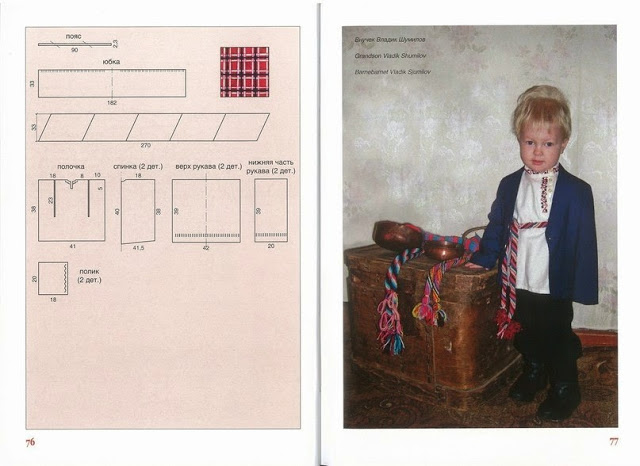

For several centuries, among Russian peasants, the men's suit was a fairly uniform complex: an untucked shirt, ports, a lower and upper caftan, a belt, a headdress, bast shoes or boots. General basis folk men's costumes manifested themselves in traditional material, cut, silhouette, ornamentation, color, ways to wear and complete costume details, architectonics (composition). Along with the unity of ideological content and structure of men’s costumes, there were some ethno-local style features, characteristic not only of specific provinces and districts, but also of individual villages.

From the 12th to the mid-19th centuries. Shirts were made mainly from linen or hemp canvas, decorating the collar, shoulders and sleeves with stripes of red-patterned fabric or embroidery. Festive shirts were made from bleached thin linen, and everyday shirts were made from coarser unbleached homespun fabric, as well as from variegated or dyed fabric. In the second half of the 19th century for sewing festive men's shirts began to buy factory fabrics: calico, Alexandria - red paper fabric with white, yellow, blue stripes, as well as calico (cheap paper fabric), chintz, semi-silk, and much less often wool.

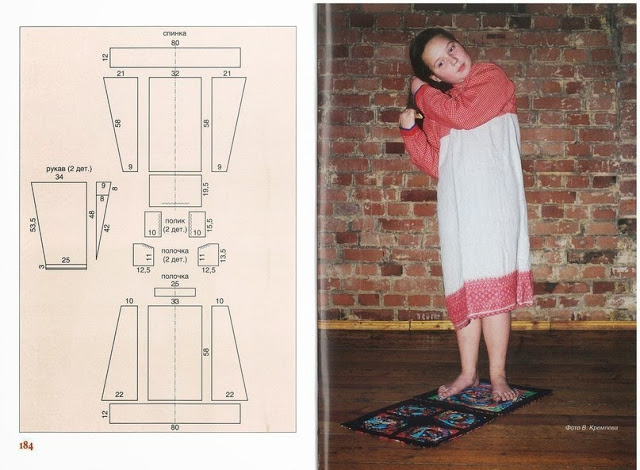

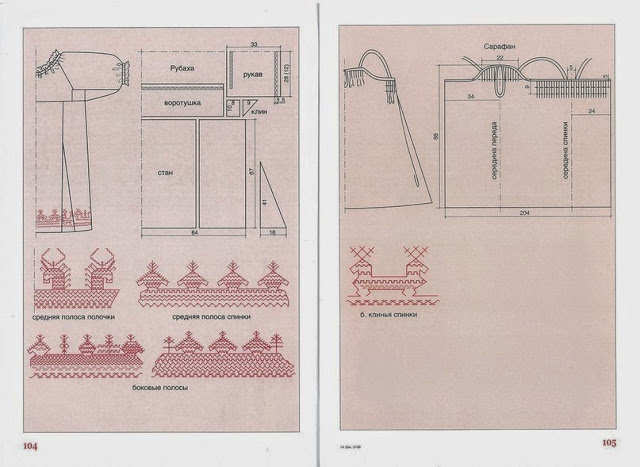

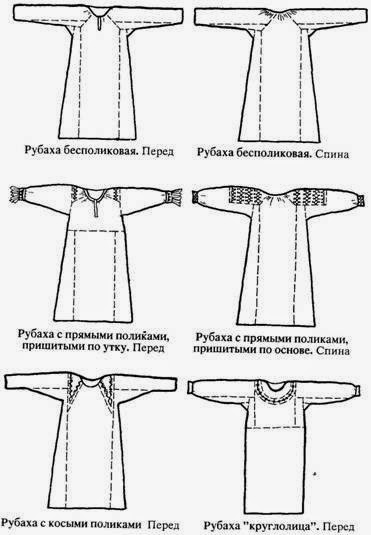

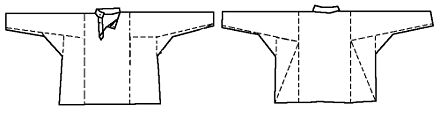

Since ancient times, a tunic-shaped shirt was known everywhere, which was sewn from a straight cloth folded in half (at the weft). A neckline was cut at the fold. Panels were sewn to the central panel to form a barrel. Straight sleeves were sewn to the central panel in a straight line. Gussets were sewn between the barrels and sleeves - square pieces of fabric, usually of a different color than the shirt. The length of such shirts reached the knees.

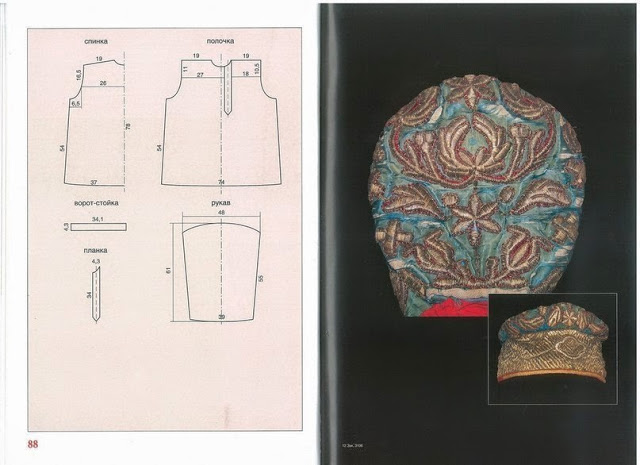

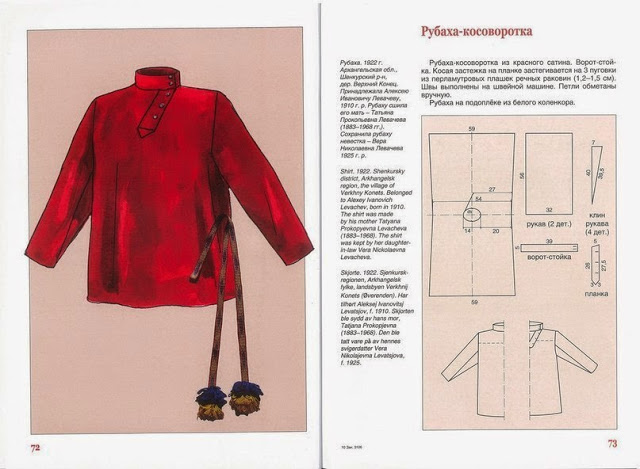

The kosovorotka, that is, a shirt with a slit on the left side of the chest, spread after the Mongol invasion. Men's peasant shirts with a stand-up collar began to be sewn in the second half of the 19th century. By the beginning of the 20th century. The cut of the shirts changed in detail: they became much shorter, there were beveled barrels, gatherings at the bottom of the sleeves, to which cuffs began to be sewn. From ancient times until the beginning of the 20th century, men's shirts were made with a "backing" - a lining sewn under the central panel.

Portas are narrow pants that the Slavs wore since ancient times, in the 18th-19th centuries. became exclusively village clothing. The trouser legs of the ports were called “snot” or “galoshes”. The galoshes were connected by an insert - a fly or rump. Everyday trousers were made from coarse canvas or woolen fabric, and festive trousers were made from high-quality wool in black, gray, blue colors with longitudinal printed patterns. Village dandies wore trousers made of pleated cotton velvet on holidays. That’s why the popular proverb says: “You can see a falcon by its flight, but a good fellow can be seen by its snot.”

By the end of the 19th century. the fashion for all kinds of vests spread. It should also be noted that the festive peasant costume usually included more clothing than the weather required: “Even in the summer, in the heat, the peasant could put on a cloth or corduroy vest, a cloth caftan, on top of it an open cloth coat and boots with galoshes.” This emphasized the wealth of the owner.

Men's outerwear was practically no different from women's and had different names: retinue, koshulya, casing, caftan, armyak, zipun, etc. It was sewn from cloth, canvas, fur with a deep smell and a fastener on the left side. By design outerwear could be robe-like and fitted (with wedges or with gathers), kaftans made of cloth and canvas could be like the colors of natural wool (in the south, mainly black or dark brown, in the north - gray, in the southeast and northwest - white and light gray colors), and blue, green and even red. We find very picturesque stories about the material, cut, and silhouette of caftans in Russian folk songs. In one of them, for example, it is sung:

I took my gold keys,

Unlocked chained chests,

She took out the black corduroy cloth,

I cut a caftan for the groom,

So that he won't be long for him,

The hem was flared,

Pinched in the middle,

Intercepted in the sinuses,

So that he can easily ride on a horsetail,

Traveled well.

The edge of the right flap of the caftan (its corner at the hem), the pocket flaps and the stand-up collar were decorated with stripes of embroidery, braid, calico, velvet, leather, buttons and appliqués.

The most elegant outerwear of Russians at all times was fur coats and sheepskin coats. Among the peasants, they were mostly sheepskin, occasionally with hare, dog or cat fur. The owners of the latter were consoled folk proverb: “Guard (dog) and Kolotkovaya (cat), but it warms no worse than sable.” They jokingly said about the dog fur coat that it guarded the house. Before the reforms of Peter I, fur coats were sewn only with the fur inside. They were covered with cloth or made naked, that is, without a cover. A sheepskin coat is an ancient symbol of family well-being. Therefore, at the wedding, when seating the bride and groom at the table on a fur coat, they said: “The fur coat is warm and shaggy - you will live warmly and richly!” During the blessing, the young people stood on a fur coat spread on the floor. We rode to get married, sitting on a fur coat laid out in the sleigh. The groom's parents greeted the newlyweds by wearing fur coats with the fur facing out.

A short fur coat - a knee-length fur caftan - was known back in the days Kievan Rus. Particularly popular were Romanov short fur coats made from the skin of sheep of the breed of the same name, bred in the Yaroslavl province. White sheepskin coats were made from white-processed, but not tanned, sheepskins. Short fur coats were made from sheepskins of red or orange color, they were also black.

An indispensable part of men's clothing was a woven, twisted, braided, knitted or belted belt. The boys girded themselves on their underwear, and the grown men - on their outer clothing. T. M. Razina writes about the very common custom of weaving belts with dedicatory inscriptions and cites, for example, the following: “You are my joy forever and you are my dear and don’t forget another, don’t love me, don’t bring me into sadness. This belt belongs to the village of Natolstik peasant daughter Elena Kuzminichna." “This belt,” notes T. M. Razina, “was given by a girl young man, who kept it all his life and in his declining years did not want to part with it."

D.K. Zelenin writes that, according to legend, the belt increased the strength of men; “the red belt, given by the wife to her husband, protected him from dashing eye, slander and other people's wives." The belt tightened and protected the abdominal muscles during heavy physical work, made clothes fit, and often served to store necessary things: an ax, a whip, a traveling knife. They were hung from the belt leather bag"kaliga" or "moshna", comb, pouch. The belt played a significant role in various ceremonies, for example, at weddings they connected the hands of the newlyweds. The bride prepared up to 20 belts for the wedding as a gift for the groom and guests.

"The marriage symbolism of the untied belt in weddings and folklore is complemented by funeral custom do not gird the deceased (untie his belt), if the remaining spouse can still enter into a new marriage, and young people who died unmarried.”

Usually young men were belted around the waist, and older men were belted along the hips to emphasize their corpulence. Overall silhouette men's suit, unlike the female one, did not hide, but emphasized the places of division of the figure.

Note that in some Russian folk songs detailed descriptions men's suits, their colors, traditional additions:

They wear sable hats, velvet tops,

Still gloomy caftans are lined with red,

Astrakhan semi-silk sashes,

Variegated shirts with gold braid.

In a famous folk song“Oh, like walking across a bridge” about the outfit good fellow it is sung like this:

Oh, how along the bridge, along the viburnum,

Just as the child walked and passed, he was wearing a blue caftan,

The floors are waving, swelling,

The calico shirt turns white,

And on the neck there is a scarf - like a scarlet flower,

And there’s another one in my pocket—Italian blue.

It was sewn and given to him by a beautiful girl-soul,

The girl-soul is beautiful, Avdotyushka is good.

The last lines of this song talk about the very common custom of village girls giving a neckerchief to a guy they like as a sign of sympathy.

Historians note the existence of a variety of hairstyles among Russian men. So, for example, A.V. Artsikhovsky writes that in the fashion of the 18th century. they had fluffy hair, cut just above the shoulders, and in the XIV-XV centuries. in the north of Rus', at least in the Novgorod and Pskov lands, men wore long hair, braiding them into braids. In the XV-XVI centuries. men cut their hair “in a circle”, “in a bracket” or cut their hair very short. But during this period, only those who lost relatives or fell into disgrace with the king grew long hair.

In many Old Believer (and not only) areas there was a custom of cutting hair; adult men, and in the Tver province also the crowns of teenagers (“gumentse”). This hairstyle was called the “crown”, considering it a symbol of immortality3. At the end of the 19th century. traditional Russian (and East Slavic) men's haircut“in a circle” (“in a bracket”) began to be replaced among young people by urban fashion. The guys parted their hair, did not cut a notch on the forehead, fluffed up their forelocks, and wore low caps and hats of semi-urban cut.

Researchers believe that shaving the beard was known to the Slavs from the Greeks and that in the Moscow state of the 16th century. wearing a beard was adopted mainly by respectable people of age and symbolized strength, masculinity and sedateness. It was believed that longer beard, the more honorable and majestic the person’s posture. Everyone who had her carried a comb with him and constantly stroked and preened her. The Orthodox clergy considered shaving the beard a pagan custom, and in 1551 at the Council of the Stoglavy it was declared that without a beard one cannot enter the kingdom of God. Therefore, representatives of the upper classes perceived the decree of Peter I, obliging them not only to abandon the stately clothes of their ancestors, but also to shave their beards as a shameful punishment. At the same time, it should be mentioned that there are many mocking proverbs created by people about bearded people:

“An apostle is an apostle by the beard, but a dog by the teeth”, “Honor is not in the beard, even a goat has a beard”, “The beard is great, but the mind is not in the least. The mustache is a catfish, but the mind is a dog!”

Headdresses had a special, prestigious significance for Russians. “After Senka and the hat,” it reads folk saying. They put on hats, slightly moving them over one ear. “To carry a hat on one ear” meant to pass in style.

Men's hats were mostly made of felted wool and came in a wide variety of shapes. Thus, in the Tver and Novgorod provinces they wore hats with a low, straight crown; in the Yaroslavl province - a low hat with a flared crown; in Vyatka, Suzdal, Perm - “buckwheat hats with a hook” or “with a break”. Festive poyark hats (made from the wool of a young sheep) were decorated with colored ribbons, peacock feathers and even artificial flowers. By the beginning of the 20th century. Such decorations were found less and less often - mainly in men's wedding suits.

Most widespread in European Russia received "felt felt" hats made of white or gray felt. Their wide brims turned up and pressed tightly against the crown. Hats with a high body (18 cm) and small brims, trimmed along the edge with a narrow strip of corduroy, were also widely used. In the non-black earth zone and northern provinces, as well as in the Voronezh province, peasants wore hats with a quadrangular bottom. The conditions of military life of the Cossacks influenced the emergence of such unique headdresses as a papakha, kubanka, military cap and an ancient Cossack hat. From the second half of the 19th century V. traditional hats began to be replaced by a cap made of factory fabric with a hard lacquered or fabric-covered visor. Since the beginning of the 20th century. The cap was gradually replaced by a cap. In winter, peasants wore sheepskin three-pieces - malakhai.

T. A. Bernshtam writes about the rules of wearing and the symbolism of a guy’s headdress, which concerns everyone Eastern Slavs:"

a) obligation holiday decoration on a hat (feathers, ribbons, flowers);

b) obligatory wearing (of a headdress) during festivities, including indoors;

c) one-time removal or lifting of the hat during a party game - for a kiss with a girl (sometimes the girl could hold the hat in her hands);

d) the absence of special prohibitions in everyday (work) environments. Thus, a guy's hungry headdress in a festive (or ritual) situation retained a ritual meaning with symbolism of single status and readiness for marriage, and an uncovered head in youth games symbolized marriage." Researchers note numerous folklore "marriage" motifs in the guy's hair and hat, and Also Special attention in a wedding ceremony to the groom's hat, which the girls try to steal (for ransom), and the groom's groomsmen try to prevent this.

At the end of the 19th century. From the city to the men's suit came the fashion for watches, chains, key chains, canes, and galoshes, which in the countryside lost their intended purpose and became fashionable “urban” items aimed at increasing the prestige of their owner. In ditties, for example, this is reflected like this:

I have galoshes

I'm saving them for summer

And in all honesty, say -

I do not have them!

On turn of XIX-XX centuries as a result of the development of crafts, otkhodnichestvo, the rapid growth of capitalist industrial production, the involvement of peasants in the sphere commodity-money relations In the villages, the fashion for urban clothing spread, which was different in material, cut, and decoration.

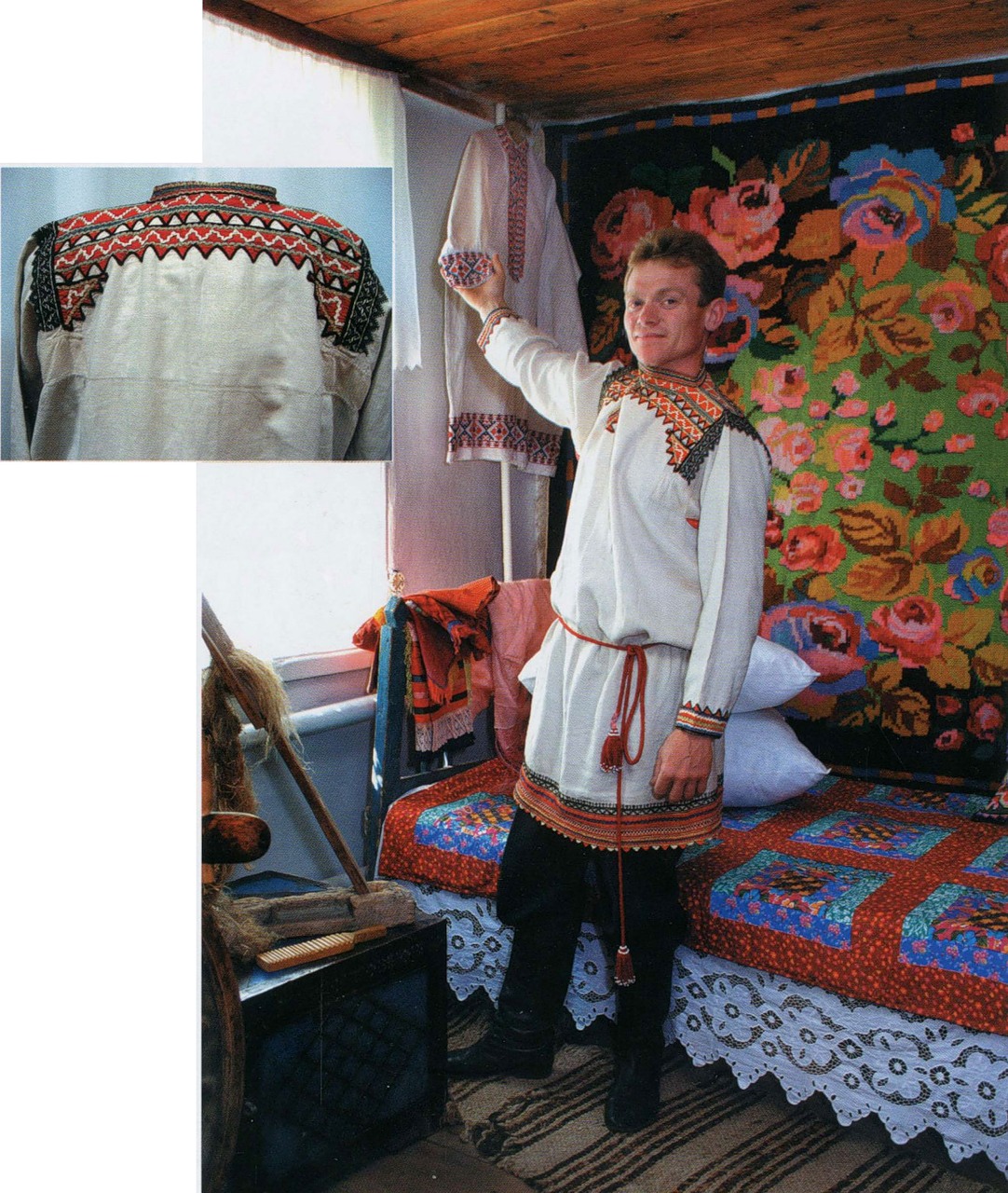

Men's clothing, unlike women's, was less diverse. It consisted of a shirt, pants, belt, headdress, and jewelry. On the territory of the Voronezh province, three types of men's shirts can be distinguished: a tunic-shaped shirt, a shirt with straight skirts sewn on a duck, a shirt with a yoke.

Tunic-shaped shirts had several cut options.

A shirt with straight sides was made from one piece of fabric, which was folded over the weft, and a cutout for the head was made at the fold. Sleeves and straight pieces of fabric were sewn to the central panel, which formed the barrel of the shirt. Rectangular gussets were sewn between the barrels and the sleeve, usually made of fabric of a different color (most often red). The shirt was sewn with a “underlay” - a lining made of rough canvas, which was hemmed at the top of the product. At the end of the 19th - first third of the 20th centuries, the “underlay” was most often made rectangular, but in some villages it was cut in the old way in the form of a triangle. In the villages of Platava and Krasnolipye, Korotoyaksky district, such a shirt was called “with a motouz” or “with a cross.” Here the seam that attached the “backing” was decorated with red embroidery, and a small cross was embroidered at the top of the triangle - in the middle of the back and front.

The tunic-shaped shirt with slanted sides was distinguished by the fact that wedges were sewn to the central panel, expanding downward.

A tunic-shaped shirt without barrels from one folded panel was made from factory material, which had a greater width than homespun canvas, which made it possible to sew shirts with such a cut.

The shirts differed in the position of the neckline, the design of the collar, and decoration.

Tunic-shaped shirts were sewn knee-length, with straight or tapering sleeves. They wore it untucked, over pants, tying it with a narrow belt, often with an overhang - a “bosom”. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, shorter shirts began to be sewn and belted around the waist.

The Russian population had shirts with a slit collar on the left side. The neck was trimmed with a narrow covering made of canvas or other material. Later, shirts with a small stand appeared. The opening of the gate was decorated with braid and small embroidery.

In Ukrainian villages, the gate cut was made straight, the neck was decorated with narrow trim, a small stand, or made turn-down. The collar was fastened with a button or tied with braid. In some Ukrainian villages, under the influence of the Russian population, shirts with a left-side cut at the collar appeared. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, both Russians and Ukrainians wore shirts in which the collar opening was covered with a beautifully embroidered placket (“shirt front”).

Men's shirt. S. Novaya Usman, Novousmansky district (Usman Sobakina, Voronezh district). From the collection of the Bogucharsky private museum of Russian folk costume and dolls

Shirts were made from homespun linen or hemp canvas white, sometimes from blue or red motley. In each locality they were decorated in accordance with established traditions. As a rule, decorations were placed on the hem, along the bottom of the sleeves, and sometimes on the shoulders. Wedding shirts and holiday shirts for young men were especially beautifully decorated.

A men's shirt with straight skirts sewn on the weft was common in the villages of Ostrogozhsky, Biryuchensky, Nizhnedevitsky, Korotoyaksky districts, in places where shirts with black stitching were distributed. Her cut was similar to that of a woman's. Poliki, top part The sleeves and bottom of the shirt were embroidered with black geometric embroidery using the “set” technique. A men's shirt with straight flaps, sewn along the weft, with three asymmetrical waist panels, is noted in the costume of the Ukrainians of the village of Endovishche, Zemlyansky district. Among the Russians, in addition to the Voronezh province, it had a local distribution in the Smolensk and Pskov provinces. The same shirts are typical for the costume of Belarusians and are known in the north of Ukraine, as well as among the Poles and Czechs.

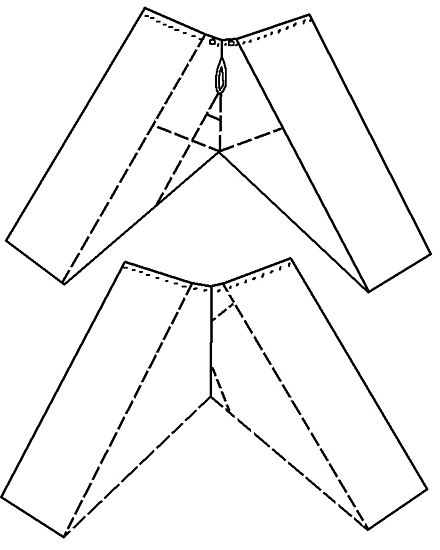

Men's belt clothing - ports or trousers - were sewn from canvas, motley fabric or printed material. The ports consisted of two trouser legs (Russian - “koloshi”, Ukrainian - “holoshni”), between which an insert was sewn (Russian - “fly”, Ukrainian - “motnya”). The ports differed in the width and length of the legs, and the shape of the insert. Among the Russian population, ports with narrow “spikes” were common, consisting of a straight panel folded over the fabric base. The legs were connected by two trapezoidal or rectangular inserts. In the upper part, the ports were assembled for restraint - “gashnik”, and later for the belt. A hole was made in the front connecting seam. The ports were made short and tucked into boots or onuchi. The Voronezh Acts of the 17th century mention warm “goat pants”. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, winter pants were made from cloth. Festive trousers for young men were made from corduroy or other factory-made fabrics in dark colors.

Ukrainians, along with narrow pants, wore wide trousers, the legs of which were cut out of two panels of fabric connected by rectangular or diamond-shaped inserts. Many researchers of folk clothing considered trousers with a low-hanging “motnya” to be a distinctive feature of the Ukrainian men’s costume. Baron August Haxthausen, who traveled to mid-19th century in Russia and visited the Voronezh region, wrote about the residents of the Ostrogozh district: “The summer clothing of men consists of white wide trousers and a white linen shirt, belted over them...”. In some counties (Biryuchensky, Valuysky, Bogucharsky) this tradition can be traced at the end of the 19th century.

Men's hats are varied in both shape and material. In Russian villages, the ancient headdress “valenka” (“elomok”, “yarmulka”), which was made from felted wool white or Brown in the shape of a truncated cone with a rounded top and bent fields adjacent to the crown.

In addition to “felt boots”, in spring and autumn they wore a felted hat made of brown wool - “sinner”. It looked like a tall cylinder with small straight brims. Treshneviki became part of the Russian men's costume no earlier than the end of the 17th century. early XVIII century, possibly from a Lithuanian costume.

In Russian villages in holidays wore black, bright hats with small brims and a high crown, which were decorated with gold or silver thread, ribbons, flowers. P. Malykhin, describing the life of the peasants of Nizhnedevitsky district in the mid-19th century, noted: “On holidays they (men - author’s note) wear colorful hats, which are decorated with peacock feathers, velvet with steel buckles and tinsel gold.”

In the village of Kochugury, Nizhnedevitsky district, N.I. Vtorov drew attention to cloth hats with a quadrangular top - “elkasy”, which were “... similar to Polish confederates.” Hats with a quadrangular bottom were widespread among all East Slavic peoples, and were made from various materials.

IN summer time Ukrainians wore wicker straw hats with a truncated flat crown and wide brim - “shaved”, “shaved”. Made hats and caps from rye straw Russian population Korotoyaksky district.

In winter, both in Russian and Ukrainian villages, men wore fur “triukhas”, cloth and corduroy hats with fur trim. In Russian villages there were cone-shaped hats knitted from wool, known throughout the entire territory inhabited by the Russian people. Distinctive feature suit Ukrainian men there were tall sheepskin hats of hemispherical or conical shape - “kuchma”.

Already in the first half of the 19th century, a cap made of factory fabric became widespread in villages, which at the end of the 19th century gradually replaced other types of summer hats. At the beginning of the 20th century, the cap came into fashion, replacing the cap in everyday life.

![]()

Tolkacheva Svetlana Pavlovna

Folk costume of the Voronezh province late XIX- early 20th century

>

>

>

>

>

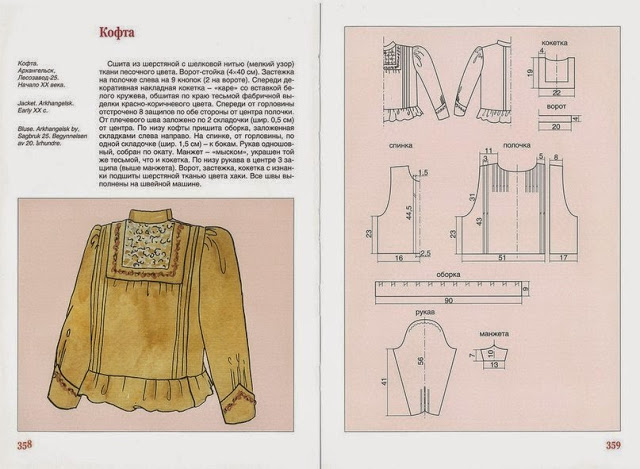

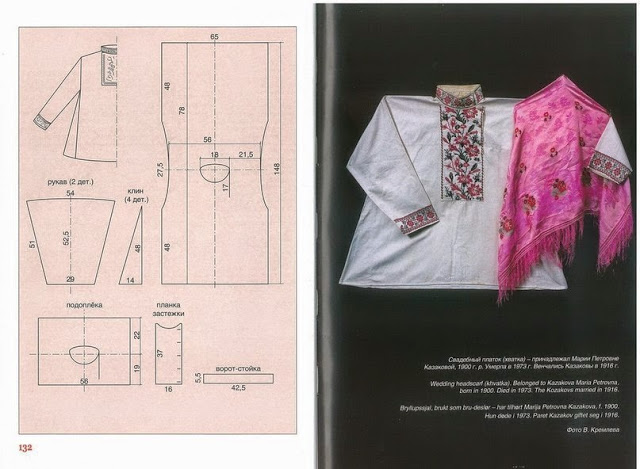

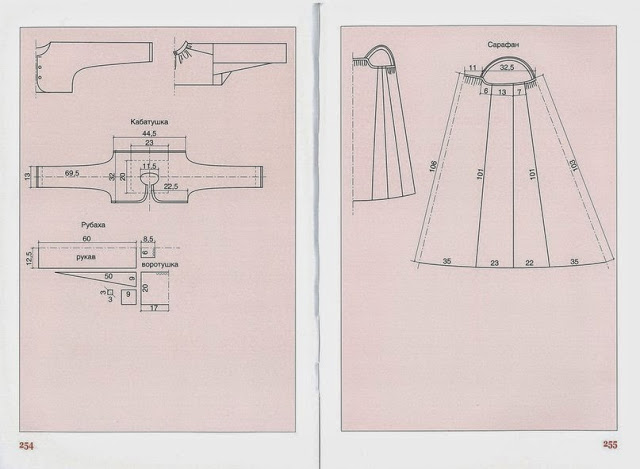

Collar shirt

Shirt

Sundress

Sundress and jacket

<

>

>

_______________________________________________________________

Shugai and sundress

>

>

>

Russian national costume

Material from Wikipedia - the free encyclopedia

E. M. Korneev. "Russian peasants", 1812

Wahlen A. Moeurs. "Russian peasants of the Tver province", 1844

Russian national costume used from ancient times to the present day. It has noticeable features depending on the specific region, purpose (holiday, wedding and everyday) and age (children, girls, married woman, old women).Despite the general similarity in cut and decoration techniques, the Russian costume had its own characteristics. In northern Russia, peasants wore clothing significantly different from peasants southern regions. IN central Russia wore a costume similar in character to the northern one, however, in some individual areas one could see a costume with features of southern Russian clothing

A distinctive feature of Russian national costume — a large number of outerwear. Cover-up and swing-out clothing. The cover-up garment was put on over the head, the swinging one had a slit from top to bottom and was fastened end-to-end with hooks or buttons.

The clothing of the nobility is of the Byzantine type. In the 17th century, borrowings from Poland appeared in clothing: Polish caftan, Polish fur coat. To protect national identity, by decree of August 6, 1675, stolniks, solicitors, Moscow nobles, residents and their servants were prohibited from wearing foreign-style clothing.

The costumes of the nobility were made from expensive fabrics, using gold, silver, pearls, and expensive buttons. Such clothes were passed down from generation to generation. The style of clothing has not changed for centuries. The concept of fashion did not exist.

Russian national costume became less common after Peter I in 1699 banned the wearing of folk costume for everyone except peasants, monks, priests and sextons. First, the Hungarian dress was introduced, and then the Upper Saxon and French, the camisole and underwear were German. Women had to wear German dress. Everyone entering the city in Russian clothes and a beard was charged a fee: 40 kopecks for those on foot and 2 rubles for those on horseback....

>

Men's clothing

Shirt-blouse

The main men's clothing was a shirt or undershirt. The first known Russian men's shirts (XVI-XVII centuries) had square gussets under the armpits and triangular gussets on the sides of the belt. Shirts were made from linen and cotton fabrics, as well as silk. The wrist sleeves are narrow. The length of the sleeve probably depended on the purpose of the shirt. The collar was either absent (just a round neck), or in the form of a stand, round or quadrangular (“square”), with a base in the form of leather or birch bark, 2.5-4 cm high; fastened with a button. The presence of a collar implied a cut in the middle of the chest or on the left (kosovorotka), with buttons or ties.

In folk costume, the shirt was the outer garment, and in the costume of the nobility it was the underwear. At home the boyars wore maid shirt— it was always silk.

The colors of the shirts are different: most often white, blue and red. They were worn untucked and girded with a narrow belt. A lining was sewn onto the back and chest of the shirt, which was called background.

Zep is a type of pocket.

Trousers. Gachi. Ports.

They were tucked into boots or onuchi with bast shoes. There's a diamond-shaped gusset in the step. A belt-gashnik is threaded into the upper part (from here cache- a bag behind the belt), a cord or rope for tying.

Outerwear

Ports. Front and back view

Over the shirt, men wore a zipun made from homemade cloth. Rich people wore a caftan over their zipun. Over the caftan, boyars and nobles wore a feryaz, or okhaben. In the summer, a single-row jacket was worn over the caftan. The peasant outerwear was the armyak.

Opashen - a long-skimmed caftan (made of cloth, silk, etc.) with long wide sleeves, frequent buttons down to the bottom and a button-down fur collar.

Scroll. The usual name for outerwear is scroll (svita). It can be either open (kaftan) or closed (overshirt). The material for the outer shirt is cloth or thick dyed linen. For a caftan - cloth, probably with a lining. The retinue was equipped with colored edging along the edges of the sleeves, usually also along the hem and collar. The outer shirt sometimes had another colored stripe between the elbow and shoulder. The cut generally corresponds to a shirt (undershirt). Along the side of the caftan there were about 8-12 buttons or ties, with conversations.

- The casing is a winter caftan.

- Korzno - ceremonial cloak.

- Bekesha - fur clothing, trimmed at the waist

The okhaben looked like a one-row shirt, but it had a turn-down collar that went down the back, and long sleeves leaned back and there were holes under them for hands, as in the single-row. A simple okhaben was made of cloth, mukhoyar, and an elegant one was made of velvet, obyari, damask, brocade, decorated with stripes and fastened with buttons. The cut of the opashen was slightly longer at the back than at the front, and the sleeves tapered towards the wrist. Opashni were sewn from velvet, satin, obyari, damask, decorated with lace, stripes, and fastened with buttons and loops with tassels. Opashen was worn without a belt (“on opash”) and saddled.

The sleeveless epancha (yapancha) was a cloak worn in bad weather. Travel cape - made of coarse cloth or camel hair. Dressy - made of good material, lined with fur.

Fur coats were worn by all layers of society: peasants wore fur coats made of sheepskin and hare, and the nobility wore fur coats made of marten, sable, and black fox. The Old Russian fur coat is massive, straight to the floor in length. The sleeves on the front side had a slit to the elbow, a wide turn-down collar and cuffs were decorated with fur. The fur coat was sewn with fur inside, and the top of the fur coat was covered with cloth. Fur has always served as a lining. The top of the fur coat was covered various fabrics: cloth, brocade and velvet. On ceremonial occasions, a fur coat was worn in the summer and indoors.

There were several types of fur coats: Turkish fur coats, Polish fur coats, the most common were Russian and Turkish.

Russian fur coats were similar to okhaben and odnoryadka, but had a wide turn-down fur collar starting from the chest. The Russian fur coat was massive and long, almost to the floor, straight, widening downwards - up to 3.5 m at the hem. It was tied in front with laces. The fur coat was sewn with long sleeves, sometimes going down almost to the floor and having slits in front up to the elbow for threading through the arms. The collar and cuff were fur.

The Tura fur coat was considered extremely ceremonial. They usually wore it saddled. It was long, with relatively short and wide sleeves.

Fur coats were fastened with buttons or gags with loops.

Hats

On the short-cropped head they usually wore tafiyas, which in the 16th century were not removed even in church, despite the censures of Metropolitan Philip. Tafya is a small round hat. Hats were put on over the tafya: among the common people - from felt, poyarka, sukmanina, among rich people - from thin cloth and velvet.In addition to hats in the form of hoods, three hats, murmolki and gorlat hats were worn. Three hats - hats with three blades - were worn by men and women, and the latter usually had cuffs studded with pearls visible from under the three hats. Murmolki are tall hats with a flat, flared crown made of velvet or brocade on the head, with a chalk blade in the form of lapels. Gorlat hats were made a cubit high, wider at the top, and narrower toward the head; they were lined with fox, mustel or sable fur from the throat, hence their name.

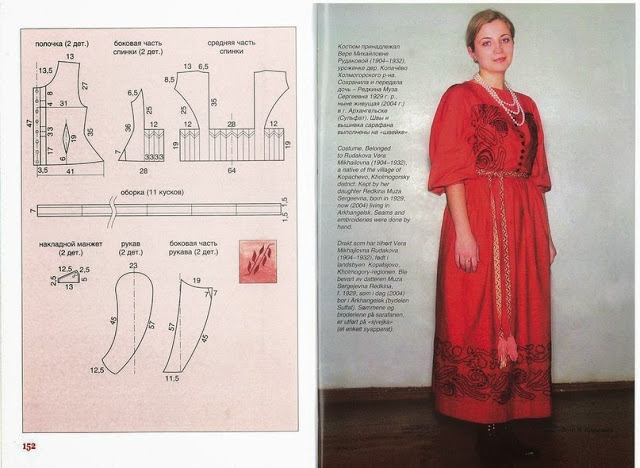

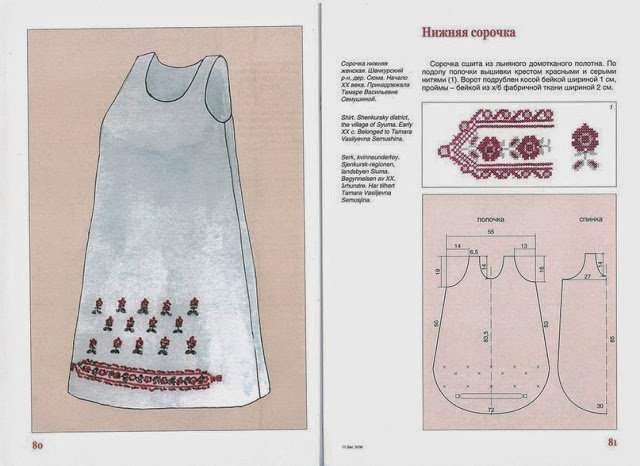

Women's clothing

The basis of a woman's costume was a long shirt. The shirt was decorated with trim or embroidery, sometimes embroidered with pearls. Noble women had outer shirts - maids. Maids' shirts were made from bright silk fabric, often red. These shirts were long narrow sleeves with a slot for hands and were called long-sleeved. The length of the sleeves could reach 8 - 10 elbows. They were gathered into folds on the hands. Shirts were belted. They were worn at home, but not when visiting. Polkas on the shirt are rectangular or wedge-shaped inserts.Women, over a white or red shirt with embroidered wrists fastened to the sleeves, wore a long silk flyer, buttoned to the throat, with long sleeves with seams (gold embroidery and pearls) and with a fastened collar (necklace).

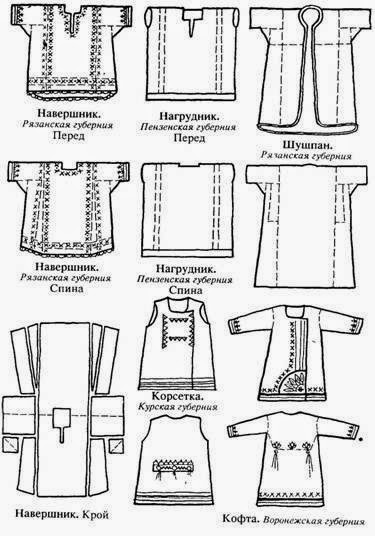

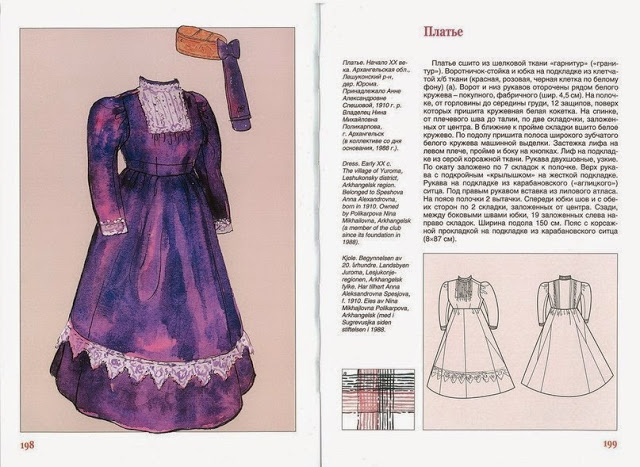

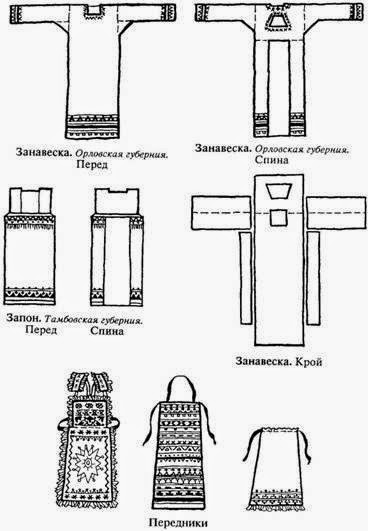

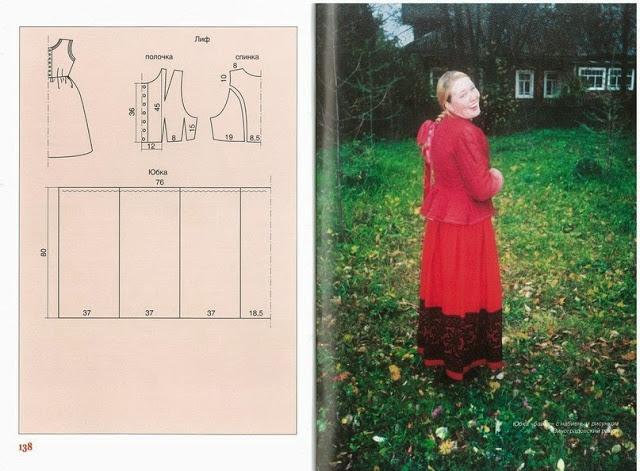

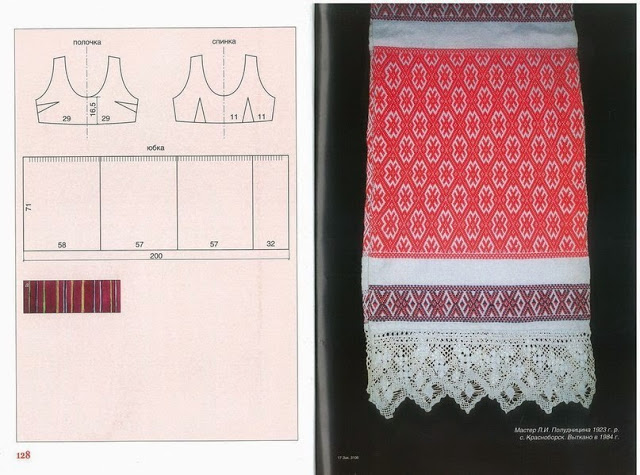

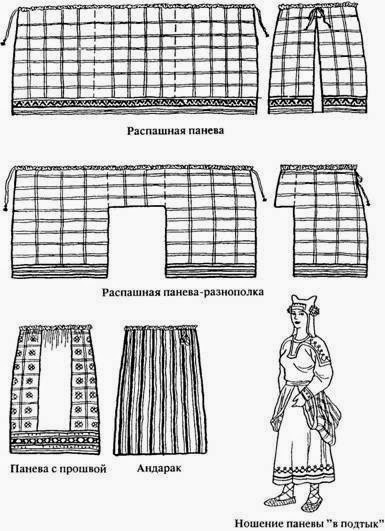

There are two main types of Russian women's costume - sarafan (northern) and ponyovny (southern) complexes:

- Sarafan is a folk Russian women's clothing in the form of a dress, most often sleeveless. Sundresses varied in fabric and cut.

- Poneva is a loincloth worn by girls who have reached the age of brides and have undergone initiation.

- Zapona is a girl's canvas clothing made from a rectangular piece of fabric, folded in half and having a hole on the fold for the head.

- Telogrea is a fur-lined or fur-lined garment with long tapered sleeves, buttoned in the front from top to hem.

- Privoloka is a sleeveless cape.

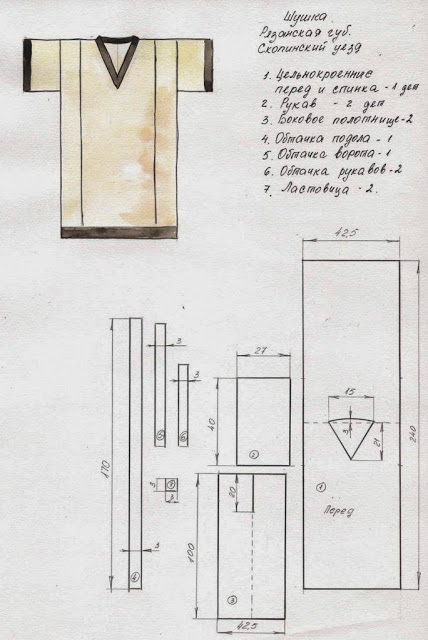

- Shushpan is a canvas caftan, with red trim, trim, and sometimes embroidered with garus.

Outerwear

Women's outerwear was not belted and was buttoned from top to bottom. Women's outerwear was a long cloth opashen, with frequent buttons, decorated at the edges with silk or gold embroidery, and the long sleeves of the opashen hung, and the arms were threaded through special slits; all this was covered with soul warmers or padded warmers and fur coats. Telogreys, if worn over the head, were called overhead ones.Noble women loved to wear fur coats- a female type of fur coat. The fur coat was similar to the summer coat, but differed from it in the shape of the sleeves. The decorative sleeves of the fur coat were long and folding. The arms were threaded through special slots under the sleeves. If a fur coat was worn in sleeves, then the sleeves were gathered into transverse gathers. A round fur collar was attached to the fur coat.

A short soul warmer was worn by all segments of the population, but for peasants it was festive clothing. Shugai and its sleeveless variety were similar to soul warmer bull.

Women also wore clothes similar to men’s: single-row, fur coats and capes.

During the time of Ivan the Terrible, rich women wore three dresses, layering one on top of the other. Wearing one dress was equated with obscenity and dishonor. The noblewoman's clothes could weigh 15 - 20 kilograms.

Muff is a sleeve sewn with fur inside and with a fur edge.

Hats

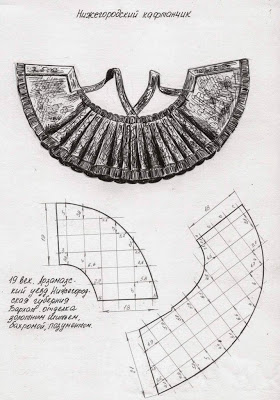

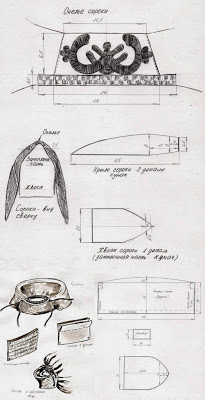

Married women had to cover their hair and therefore wore it on their heads at home. volosniki or warriors and tied it with a scarf, and when leaving home they put on a richly decorated kika or kokoshnik. The girls wore a wide embroidered bandage (corolla) on their heads, with wide ribbons behind. In winter, women wore fur hats or covered their headdress with a scarf.Other distinguishing feature Russian national costume - a wide variety of women's headdresses:

- Kichka (kika) is a festive headdress for a married woman.

- Soroka is a type of bandage with a hard band.

- Kokoshnik - in the form of a comb (fan or rounded shield) around the head, a symbol of Russian traditional costume.

- Povoinik - a soft cap that completely covered the hair braided during wedding ceremony from one girl's braid at two.

Shoes

- Lapti- low shoes woven from tree bast. For strength, the sole was braided with vine, bast, rope or hemmed with leather. The bast shoe was tied to the leg with laces twisted from the same bast from which the bast shoes themselves were made.

- Shoes— made of leather and tied with laces.

- Cheboty- a type of boot with a short top. Chebots were made of morocco, expensive ones - from satin and velvet. Chobots are straight and crooked. Crooked chebots had toes turned up.

- Ichigi- a type of lightweight shoe shaped like a boot, with a soft toe and an internal hard heel.

- Felt boots— warm felt boots made of felted sheep wool; Most often they are made hard, but they can also be soft, suitable for other shoes.

- Onuchi- a long, wide (about 30 cm) strip of white, black or brown fabric (canvas, wool) for wrapping the leg up to the knee (when putting on bast shoes).

- Pistons- the simplest Russian leather shoes.

Boots with short, below-the-knee, tops cut off at an angle to the knee. Boots were made from colored leather, morocco, velvet, brocade, and were often decorated with embroidery. Horseshoes and nails could be silver, socks and heels were decorated with pearls and precious stones.

At the end of the 17th century, the nobility began to wear low shoes.

Women wore boots and shoes. Shoes were made from velvet, brocade, leather, initially with soft soles, and from the 16th century - with heels. heel on women's shoes could reach 10 cm.

Fabrics

The main fabrics were: horse and linen, cloth, silk and velvet. Kindyak - lining fabric.The clothes of the nobility were made from expensive imported fabrics: taffeta, damask (kufter), brocade (altabas and aksamite), velvet (regular, dug, gold), roads, obyar (moiré with gold or silver pattern), satin, konovat, kurshit, kutnya (Bukhara half-wool fabric). Cotton fabrics (Chinese, calico), satin (later satin), calico. Motley is a fabric made of multi-colored threads (semi-silk or canvas).

Clothes colors

Fabrics used bright colors: green, crimson, lilac, blue, pink and variegated. Most often: white, blue and red.Other colors found in the inventories of the Armory: scarlet, white, white grape, crimson, lingonberry, cornflower blue, cherry, clove, smoky, erebel, hot, yellow, grass, cinnamon, nettle, red-cherry, brick, azure, lemon, lemon Moscow paint, poppy, aspen, fiery, sand, praselen, ore yellow, sugar, gray, straw, light green, light brick, light gray, gray-hot, light tsenin, tausin (dark purple) , dark clove, dark gray, worm-like, saffron, valuable, forelock, dark lemon, dark nettle, dark purple.

Later black fabrics appeared. Since the end of the 17th century, black began to be considered a mourning color.

.......................

>

>

>

...........................

Decorations

Andrey Ryabushkin. A merchant's family in the 17th century. 1896

Large buttons on women's clothing, on men's clothing patches with two button sockets. Lace at the hem.

The cut of the clothing remains unchanged. The clothes of rich people are distinguished by a wealth of fabrics, embroidery, and decorations. They sewed along the edges of the clothes and along the hem lace- wide border made of colored fabric with embroidery.

The following decorations are used: buttons, stripes, removable necklace collars, sleeves, cufflinks. Cufflinks - buckle, clasp, forged plaque with precious stones. The sleeves and wrists are cuffs, a kind of bracelet.

All this was called an outfit, or the shell of a dress. Without decorations, clothes were called clean.

Buttons

Buttons were made from different materials, various forms and sizes. The wooden (or other) base of the button was trimmed with taffeta, entwined, covered with gold thread, spun gold or silver, and trimmed with small pearls. During the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, diamond buttons appeared.Metal buttons were decorated with enamel, precious stones, and gold. Shapes of metal buttons: round, four- and octagonal, slotted, half-shaped, senchaty, twisted, pear-shaped, in the form of a cone, a lion's head, crucian carp, and others.

Klyapyshi is a type of button in the form of a bar or stick.

Patches

Stripes are transverse stripes according to the number of buttons, sometimes with ties in the form of tassels. Each patch had a buttonhole, so later the patches came to be called buttonholes. Until the 17th century, stripes were called patterns.The patches were made from braid three inches long and half or up to one inch wide. They were sewn on both sides of the clothing. The rich outfit has stripes made of gold fabrics. The braid of the stripes was decorated with patterns in the form of herbs, flowers, etc.

The stripes were placed on the chest to the waist. In some suits, stripes were placed along the entire length of the cut - to the hem, and along the holes - on the side cutouts. The stripes were placed at equal distances from each other or in groups.

Patches could be made in the form of knots - a special weaving of cord in the form of knots at the ends.

In the 17th century, Kyzylbash stripes were very popular. Kyzylbash masters lived in Moscow: master of patchwork Mamadaley Anatov, master of silk and weaving master Sheban Ivanov with 6 comrades. Having trained Russian masters, Mamadaley Anatov left Moscow in May 1662.

: Necklace collar)

Necklace - an elegant collar in clothes made of satin, velvet, brocade embroidered with pearls or stones, fastened to a caftan, fur coat, etc. The collar is stand-up or turn-down.Other decorations

Temporal rings - colts. Neck hryvnia.Accessories

The men's costume of the nobility was complemented by mittens with gauntlets. Mittens could have rich embroidery. Gloves (pepper sleeves) appeared in Rus' in the 16th century. A wicket bag was hung from the belt. IN special occasions they held a staff in their hand. The clothes were belted with a wide sash or belt. In the 17th century they began to often wear trump- high stand-up collar.Flasks (flasks) were worn on a sling. The flask could contain a watch. Sling - gold chain, sewn to a satin stripe.

Women wore fly- a scarf cut across the entire width of the fabric, sleeves (fur muffs) and a large amount of jewelry.

........................................................ ........................................................ ................................................... Sundress