The most popular character in Italian commedia dell'arte. M

COMEDY DEL ARTE (commedia dell"arte); another name is comedy of masks, improvisational street theater Italian Renaissance, which arose in the mid-16th century. and, in fact, formed the first professional theater in history.

Commedia dell'arte emerged from street festivals and carnivals. Her characters are certain social images in which not individual, but typical traits are cultivated. There were no plays as such in the commedia dell'arte; only a plot scheme, a script, was developed, which during the course of the performance was filled with live replicas that varied depending on the composition of the audience.

It was this improvisational method of work that led comedians to professionalism - and, first of all, to the development of an ensemble, increased attention to a partner. In fact, if the actor does not carefully follow the improvisational cues and the line of behavior of the partner, he will not be able to fit into the flexibly changing context of the performance. These performances were the favorite entertainment of the mass, democratic audience. Commedia dell'arte absorbed the experience of farcical theater, but the common characters of the "scientific comedy" were also parodied here. A specific mask was assigned to a specific actor once and for all, but the role - despite the rigid typical framework - varied endlessly and developed during each performance.

The main characters of the commedia dell'arte

The number of masks in commedia dell'arte is very large (there are more than a hundred of them in total), but most of them are related characters that differ only in names and minor details. The main characters of the comedy include two quartets of male masks, the Captain's mask, as well as characters who do not wear masks, these are the Zanni girls and the Lovers, as well as all the noble ladies and gentlemen.

Male characters

Northern (Venetian) quartet of masks:

Pantalone

Magnifico, Cassandro, Uberto

- Origin: Venetian with his typical dialect.

- Class: old merchant, rich, almost always stingy.

- Costume: Pantalone wears very tight red pants (pantalons), a short vest-jacket of the same color. He wears a woolen cap and a long black cloak, and yellow slippers. He wears a gray mustache and a thin gray beard.

- Mask: his mask is red or brown (earthy) in color and covers half of his face; he has a long, aquiline nose, a gray mustache and a pointed beard, which should produce a special comic effect when he talks.

- Behavior: Pantalone is usually the center of intrigue, and, as a rule, always remains the victim of someone, most often Harlequin, his servant. He is sick and frail: he constantly limps, groans, coughs, sneezes, blows his nose, and has a stomach ache. This is a lustful, immoral man, he passionately seeks the love of young beauties, but always fails. His gait is that of an old man; he walks with a slightly crooked back. He speaks in a harsh, shrill, “old man” voice.

Doctor

Dr. Balandzone, Dr. Graziano

- Origin: Bolognese lawyer, with a harsh, rough dialect.

- Class: pseudo-scientific doctor of law (very rarely - doctor of medicine, then enemas, chamber pots, dirty linen, etc. were added to his costume)

- Costume: A long black robe is required, under which he wears a black jacket and black short trousers, black shoes with black bows, a black leather belt, and a black cap on his head. The suit is completed with white cuffs, a wide white collar around the neck and a white scarf tucked into the belt.

- Mask: black in color with a huge nose, usually covers the entire face, but sometimes only the forehead and nose, then the Doctor’s cheeks are thickly rouged.

- Behavior: like Pantalone, he is an old man deceived by other characters in the comedy. This man is very fat, his stomach protrudes forward, makes it difficult to move freely and is clearly visible. It is difficult for him to bend over and walk. He is as lustful as Pantalone. He is a vain, ignorant pedant, speaking in incomprehensible Latin terms and quotes, which he mercilessly misinterprets. A little eccentric and very fond of wine.

The Doctor's Mask required a very good command of the Bolognese dialect, as well as great erudition in order to improvise and create comic effect from scraps of knowledge.

Brighella

Scapino, Buffetto

- Origin: a former peasant, a native of Bergamo, speaking a clipped, monosyllabic, ending-eating Bergamo dialect.

- Class: servant.

- Costume: a linen blouse, long trousers, a cloak and a white cap - a white suit trimmed with green braid; yellow leather shoes. There is a black pouch at the belt, and a dagger (sometimes wooden, but more often real) behind the belt.

- Mask: hairy, dark in color with a black mustache and a black beard sticking out in all directions.

- Behavior: a clever and resourceful, often thieving servant; cheeky with women, insolent with old people, brave with cowards, but helpful to the strong; always loud and talkative. At first angry and ruthless, by the 18th century. Brighella becomes softer and more cheerful. He is always against old people who prevent young people from living, loving and achieving happiness. The actors playing this mask are required to be able to play the guitar and master basic acrobatic tricks.

Harlequin

Mezzetino, Truffaldino, Tabarino

- Origin: A native of Bergamo who moved in search of better life to the richest city - Venice.

- Class: servant.

- Costume: a peasant shirt and trousers, trimmed with multi-colored patches - pieces of fabric in the shape of rhombuses. The costume is very colorful; mostly yellow, but there are pieces of different colors - green, blue, red. On his head he wears a cap decorated with a bunny tail. There is a purse on the belt. He wears very light shoes that allow him to move freely and perform acrobatic tricks.

- Mask: black with a huge wart on his nose. The forehead and eyebrows are deliberately highlighted, with black tousled hair. Sunken cheeks and round eyes indicate his gluttony.

- Behavior: Harlequin is cheerful and naive, not as smart, not as dexterous, not as resourceful as Brighella, so he easily commits stupid things, but he accepts the subsequent punishments with a smile. He is lazy and looks for any opportunity to evade work and take a nap, he is a glutton and a womanizer, but at the same time he is polite and modest. And if Brighella evokes admiration for his dexterity, then Harlequin should evoke sympathy for his funny misfortunes and childish sorrows.

Southern (Neapolitan) mask quartet

Tartaglia

- Origin: Spaniard who speaks poor English Italian.

- Class: an official in the public service: he can be a judge, a policeman, a pharmacist, a notary, a tax collector, etc.

- Costume: a stylized official suit, a uniform hat on his bald head; On the nose huge glasses.

- Behavior: as a rule, he is an old man with a fat belly; Always a stutterer, his signature trick is the fight against stuttering, as a result of which a serious monologue, for example, in court, turns into a comic stream of obscenities.

Scaramuccia

Scaramucci's mask partly repeated the northern mask of the Captain, but carried less political satire. This was no longer a Spanish invader, but a simple type of boastful warrior, close in spirit to some of Plautus’s characters. He is boastful, loves to scold, but as soon as it comes to a fight, he cowardly runs away or, if he does not have time to escape, will invariably be beaten.

Scaramucci's mask also gave rise to the characters Pasvariello (the servant, drunkard and glutton), Pasquino (the cunning and deceitful servant) and, in France, Crispen (the roguish servant).

Coviello

- Origin: a former peasant, native of Cava or Acerra (ancient cities near Naples), speaking a vibrant Neapolitan dialect.

- Class: servant.

- Costume: wears a tight suit, but can sometimes be dressed in simple trousers and a vest; often with a sword and a beating stick in his belt; wears a hat with feathers.

- Mask: red in color, with a long, beak-like nose; often wears glasses.

- Behavior: always acts with cunning, pressure, clever invention, intelligence; grimaces a lot, dances and plays the mandolin or guitar).

Pulcinella

- Origin: a peasant who moved to the city from ancient Acerra near Naples.

- Class: a servant, but can also act as a gardener and as a watchman, can be a merchant, artist, soldier, smuggler, thief, bandit.

- Costume: clothes made of coarse hemp material, wearing a tall, pointed hat.

- Mask: with a large “rooster” or hooked nose (priapic type).

- Behavior: a hunchback speaking in a high, shrill voice. The main feature of his character is stupidity, but not always: he can be smart and dexterous, like Brighella (however, it is important that the image created on stage is uniform and reveals one thing - either Pulcinella’s cunning or stupidity). His negative qualities are laziness, gluttony, and criminal tendencies. He spews witticisms, often quite obscene.

*****

Captain

Origin: Spain. He spoke broken Italian and sprinkled his speech with Spanish words.

Class: soldier.

Costume: The captain wore a somewhat cartoonish military suit of Spanish cut.

Mask: the actor playing the Captain performed without a mask.

Behavior: The image of the Captain is distinguished by great satirical sharpness. This is a coward pretending to be brave, a boastful warrior, similar to the warrior from the plays of Plautus. He is characterized by cold arrogance, greed, cruelty, primness and bluster hiding cowardice. When one of the characters orders him to do something or forces him to commit a decisive act, he retreats and looks for an excuse to refuse to carry out the order or a reason why he cannot perform the act. At the same time, the Captain tries not to lose face, using pompous speech and bravado. His conversations contain many wild tales that even the most gullible viewers do not believe. The captain loves female society, where he brags about the exploits he has invented. Columbine, using the Captain, makes Harlequin jealous.

Female characters

Isabel

also, Lucinda, Vittoria, etc.

Young lover; often the heroine was named after the actress who played this role.

Columbine

Fantesca, Fiametta, Smeraldina

Origin: a peasant girl who feels insecure and unusual in the city.

Class: a servant, usually under Pantalon or the Doctor, a zanni girl.

Costume: usually dressed in a beautiful fluffy dress; in later theater (from the 18th century) he often appears in a dress made of patches, similar to a Harlequin costume.

Mask: doesn't wear a mask.

Behavior: initially, this is a village fool, similar in character to the Harlequin mask; Her honesty and decency are emphasized, as well as her always good mood. In the French theater, Fanteschi's peasant features were erased, and the mask acquired the character of a typical French soubrette.

Lovers

A pair of young lovers, sure to be present in any scenario. In a good troupe there were always two such couples.

Unlike the comic characters of the comedy, they never wear masks and are always dressed in expensive suits, their speech is refined - they speak the Tuscan dialect, i.e. in literary Italian. They rarely improvise; their speeches are usually memorized. Lovers can wear different names, most often, Lelio, Orazio, Flavio, Florindo for boys and Isabella, Vittoria, Flaminia for girls; they may also be named after the actors playing these roles.

Components of commedia dell'arte

Masks

A leather mask was a mandatory attribute covering the face of a comic character, and was initially understood exclusively in this sense. However, over time, the entire character began to be called a mask. The actor usually played the same mask. The actor who played Brighella rarely had to play Pantalone, and vice versa. The scripts changed often, but the mask changed much less often. The mask became the image of the actor, which he chose at the beginning of his career, and playing it all his life, he complemented it with his artistic individuality. He did not need to know the role, it was enough to know the script - the plot and the proposed circumstances. Everything else was created during the performance process through improvisation.

The organization of the troupe and the canon of the performance

System performing arts Commedia dell'arte was formed by the end of the 16th century. and improved over the next century. In 1699, the most complete code of comedy, “Dell'arte representiva, premediata e all'improviso,” compiled by Andrea Perucci, was published in Naples.

The performance begins and ends with a parade with the participation of all the actors, with music, dance, lazzi (buffon tricks) and tomfoolery, and consists of three acts. Short interludes were performed between acts. The action must be limited in time (twenty-four-hour canon). The plot scheme was also canonical - young lovers, whose happiness is hindered by old people, overcome all obstacles with the help of clever servants. The troupe must have a capocomico who reviews the script with the actors, deciphers the lazzi and takes care of the necessary props. The script is selected strictly in accordance with the masks that the troupe has. This is at least one quartet of masks and a pair of lovers. Also, a good troupe should have two more actresses, a singer (Italian: la cantatrice) and a dancer (Italian: la ballarina). The number of actors in the troupe was rarely less than nine, but usually did not exceed twelve. For the scenery it was necessary to designate a street, a square, two houses in the background, on the right and on the left, between which the backdrop was stretched.

Script and improvisation

The basis of a performance in commedia dell'arte is the script (or outline) - this is a very brief summary of the plot episodes with a detailed description characters, the order of entering the stage, the actions of the actors, the main lazzi and props. Most scripts are reworkings of existing comedies, short stories and short stories for the needs of a single troupe (with its own set of masks), a hastily scribbled text posted backstage during the performance. The script, as a rule, is of a comedic nature, but it can also be a tragedy, a tragicomedy, or a pastoral (in the collection of scripts by Flaminio Scala, which were played on stage by the Gelosi troupe, there are tragedies; it is also known that the Moliere-Dufresne troupe traveling around the French province sometimes she played tragedies, however, without much success).

Here the art of improvisation of Italian comedians came into force. Improvisation allows you to adapt the play to a new audience, to the news of the city; an improvisational performance is more difficult to subject to preliminary censorship. The art of improvisation consisted in resourceful delivery of lines combined with appropriate gestures and the ability to reduce all improvisation to the original script. Successful improvisation required temperament, clear diction, mastery of recitation, voice, breathing, and good memory, attention and resourcefulness, requiring an instant reaction, and rich imagination, excellent control of the body, acrobatic dexterity, the ability to jump and somersault over the head were required - pantomime, as a body language, acted on a par with the word. In addition, actors playing the same mask throughout their lives accumulated a solid baggage of stage techniques, tricks, songs, sayings and aphorisms, monologues and could freely use this in a variety of combinations. Only in the 18th century. playwright Carlo Goldoni led Italian drama from the script to the fixed text; he buried the commedia dell'arte, which was in decline, and on its grave erected an immortal monument in the form of the play "The Servant of Two Masters."

Dialects

Dialect was one of the necessary elements characterizing the mask. First of all, this concerns comic and buffoon masks, since noble masks, ladies, gentlemen and lovers, speak literary language Italy, i.e. in the Tuscan dialect in its Roman pronunciation. The dialect complements the character's characteristics, indicating his origin, and also gives its own comic effect.

Materials used from Wikipedia and the Around the World encyclopedia

Commedia dell'arte (Italian commedia dell'arte), or comedy of masks, is a type of Italian folk (square) theater, performances of which were created by the method of improvisation, based on a script containing a brief plot outline of the performance, with the participation of actors dressed in masks. different sources also referred to as la commedia a soggetto (script theatre), la commedia all'improvviso (improvisation theatre) or la commedia degli zanni (zanni comedy).

The theater existed from the mid-16th to the end of the 18th centuries, having a key impact on the further development of all Western European drama theater. The commedia masque troupes were the first professional theater troupes in Europe, where the foundations of acting were laid (the term commedia dell'arte, or skillful theater, indicates the perfection of actors in theatrical acting) and where for the first time elements of directing were present (these functions were performed by the leading actor of the troupe , called capocomico, Italian capocomico).

By the 19th century, commedia dell'arte was becoming obsolete, but found its continuation in pantomime and melodrama. In the 20th century, comedy served as a model for the synthetic theater of Meyerhold and Vakhtangov, as well as the French Jacques Copot and Jean-Louis Barrault, who revived the expressiveness of stage gesture and improvisation and gave great importance ensemble playing.

The principle of tipi fissi, in which the same characters (masks) participate in scenarios with different contents, is widely used today in the creation of comedy television series, and the art of improvisation is used in stand-up comedy.

Origin

In the ancient Roman theater there was a type of folk theater called atellans. These were obscene farces, originally improvised, in which the actors also wore masks; Some of the characters of the Atellans were similar in the nature of the mask to the characters of the Commedia dell'Arte (such as the Roman mask of Papus and the Italian mask of Pantalone), but it is wrong to talk about the Atellans as the predecessor of the Commedia dell'Arte - the gap in tradition between them is more than twelve centuries . Most likely, we can only talk about the similarity of circumstances in which these types of theater were born.

Commedia dell'arte was born from carnival celebrations. There was no theater yet, but there were jesters, mimes, and masks. Another factor was the emergence of national Italian drama. New plays are being written by L. Ariosto, N. Machiavelli, B. Bibiena, P. Aretino, but all these plays are not suitable for the stage; they are oversaturated with characters and an abundance of plot lines. This dramaturgy is called “scientific comedy.”

Angelo Beolco (Rudzante) in the first half of the 16th century. composes plays using the technique of “scientific comedy”, but performs his performances at the Venetian carnivals. The confusing plots are accompanied by tricks and healthy peasant humor. A small troupe gathers around him, where the principle of tipi fissi is outlined and the use of folk dialect speech on the theatrical stage is approved. Finally, Beolko introduced dramatic action dance and music. This was not yet a commedia dell'arte - Beolko and his troupe were still playing within the framework of a given plot, he did not have free play and improvisation, but it was he who opened the way for the emergence of comedy. The first mention of the mask theater dates back to 1555.

The main characters of the commedia dell'arte

The number of masks in commedia dell'arte is very large (there are more than a hundred of them in total), but most of them are related characters that differ only in names and minor details. The main characters of the comedy include two quartets of male masks, the Captain's mask, as well as characters who do not wear masks, these are the Zanni girls and the Lovers, as well as all the noble ladies and gentlemen.

Male characters

Northern (Venetian) mask quartet

Pantalone(Magnifico, Cassandro, Uberto) - Venetian merchant, stingy old man;

Doctor(Dr. Balandzone, Dr. Graziano), - pseudo-scientific doctor of law; old man;

Brighella(Scapino, Buffetto), - the first zanni, clever servant;

Harlequin(Mezzetino, Truffaldino, Tabarino) - second zanni, stupid servant;

Southern (Neapolitan) mask quartet

Tartaglia, judge-stutterer;

Scaramuccia, boastful warrior, coward;

Coviello, first zanni, intelligent servant;

Pulcinella(Policinelle), second zanni, stupid servant;

Captain, - a boastful warrior, a coward, the northern analogue of the Scaramucci mask;

Pedrolino(Pierrot, Clown), servant, one of the zanni.

Lelio(also, Orazio, Lucio, Flavio, etc.), young lover;

Female characters

Isabel(also, Lucinda, Vittoria, etc.), young lover; often the heroine was named after the actress who played this role;

Columbine

Columbina, Fantesca, Fiametta, Smeraldina, etc., are maids.

Components of commedia dell'arte

Masks

A leather mask (Italian maschera) was a mandatory attribute covering the face of a comic character, and was initially understood exclusively in this sense. However, over time, the entire character began to be called a mask. The actor usually played the same mask. The actor who played Brighella rarely had to play Pantalone, and vice versa. The scripts changed often, but the mask changed much less often. The mask became the image of the actor, which he chose at the beginning of his career, and playing it all his life, he complemented it with his artistic individuality. He did not need to know the role, it was enough to know the script - the plot and the proposed circumstances. Everything else was created during the performance process through improvisation.

The organization of the troupe and the canon of the performance

Harlequin, thief, provost and judge

The system of performing arts of commedia dell'arte was formed by the end of the 16th century. and improved over the next century. In 1699, the most complete code of comedy, “Dell'arte representiva, premediata e all'improviso,” compiled by Andrea Perucci, was published in Naples.

The performance begins and ends with a parade with the participation of all the actors, with music, dance, lazzi (buffon tricks) and tomfoolery, and consists of three acts. Short interludes were performed between acts. The action must be limited in time (twenty-four-hour canon). The plot scheme was also canonical - young lovers, whose happiness is hindered by old people, overcome all obstacles with the help of clever servants. The troupe must have a capocomico who reviews the script with the actors, deciphers the lazzi and takes care of the necessary props. The script is selected strictly in accordance with the masks that the troupe has. This is at least one quartet of masks and a pair of lovers. Also, a good troupe should have two more actresses, a singer (Italian: la cantatrice) and a dancer (Italian: la ballarina). The number of actors in the troupe was rarely less than nine, but usually did not exceed twelve. For the scenery it was necessary to designate a street, a square, two houses in the background, on the right and on the left, between which the backdrop was stretched.

Script and improvisation

The basis of a performance in commedia dell'arte is the script (or outline) - this is a very brief episode-by-episode summary of the plot with a detailed description of the characters, the order of entering the stage, the actions of the actors, the main scenes and props. Most scripts are reworkings of existing comedies, short stories and short stories for the needs of a single troupe (with its own set of masks), a hastily scribbled text posted backstage during the performance. The script, as a rule, is of a comedic nature, but it can also be a tragedy, a tragicomedy, or a pastoral (in the collection of scripts by Flaminio Scala, which were played on stage by the Gelosi troupe, there are tragedies; it is also known that the Moliere-Dufresne troupe traveling around the French province sometimes she played tragedies, however, without much success).

Here the art of improvisation of Italian comedians came into force. Improvisation allows you to adapt the play to a new audience, to the news of the city; an improvisational performance is more difficult to subject to preliminary censorship. The art of improvisation consisted in resourceful delivery of lines combined with appropriate gestures and the ability to reduce all improvisation to the original script. Successful improvisation required temperament, clear diction, command of recitation, voice, breathing, good memory, attention and resourcefulness, requiring instant reaction, and rich imagination, excellent body control, acrobatic dexterity, the ability to jump and somersault over the head - pantomime was required , as body language, acted on a par with words. In addition, actors playing the same mask throughout their lives accumulated a solid baggage of stage techniques, tricks, songs, sayings and aphorisms, monologues and could freely use this in a variety of combinations. Only in the 18th century. playwright Carlo Goldoni led Italian drama from the script to the fixed text; he buried the commedia dell'arte, which was in decline, and on its grave erected an immortal monument in the form of the play "The Servant of Two Masters."

Oh, no matter how much I persuaded Irina Anatolyevna, she flatly refuses to do a webinar on commedia dell’arte, with which I have so many wonderful memories!

What to do, humor that is appropriate at the moment is not always classic joke, capable of cheering even through the centuries. But the entire dramaturgy of the commedia dell'arte arose from improvisation.

The masks of traditional characters were supposed to be somewhat superior to the bright masks of the Venetian carnival. It’s strange, but in the homeland of this theater, Angelo Beolco, almost unknown in our country, is considered the founder. But we are more familiar with this theater from the work of his compatriot Carlo Goldoni, who worked two hundred years later.

The theater existed in almost unchanged form from the mid-16th to the end of the 18th centuries, having a significant impact on the further development of Western European dramatic theater.

The troupes that played comedies of masks were the first professional theater troupes in Europe, where the foundations of acting were laid (the term commedia dell'arte, or artful theater, indicates the perfection of actors in theatrical acting) and where elements of directing were present for the first time. These functions were performed by the leading actor of the troupe, called Kapokomiko(Italian capocomico).

The troupes that played comedies of masks were the first professional theater troupes in Europe, where the foundations of acting were laid (the term commedia dell'arte, or artful theater, indicates the perfection of actors in theatrical acting) and where elements of directing were present for the first time. These functions were performed by the leading actor of the troupe, called Kapokomiko(Italian capocomico).

Commedia dell'arte (Italian: commedia dell'arte) is a comedy of masks, a type of Italian folk (square) theater. The predecessors of commedia dell'arte were the performances of minstrels and traveling actors, strongmen and clowns, jugglers and magicians; even comic demons from liturgical drama influenced its development.

It’s interesting that Russia also had canonical puppet characters. We had one traveling actor who was a kind of one-man orchestra. According to Olearius, the actors tied a sheet around their body, lifted its free part up and held it above their heads on poles, thus forming something like a stage. With a folk comedy about Petrushka, who defeated first a priest, then a master, then a doctor, the actors walked the streets, showing puppet shows.

In commedia dell'arte there was a strict set of masks corresponding to the actors' roles. The performances were created using the method of improvisation, based on a script containing a brief plot outline of the performance, with the participation of actors dressed in masks. Various sources also refer to it as la commedia a soggetto (script theatre), la commedia all’improvviso (improvisation theatre) or la commedia degli zanni (zanni comedy).

This is a theater that required the actor to play well-coordinatedly in the troupe, reacting flexibly and accurately to each cue within the framework of the accepted image. The actor's role here also included the development of the dramaturgy of his albeit conventional image, but right in front of the audience, often entering into a skirmish with them.

Geiger Richard "Pierrot and Columbine"

The peak of popularity of improvisational comedy with permanent characters moving from performance to performance occurred in the years 1560-1760. The performances were performed by professional actors - unlike the previous era, when amateurs performed in the theater.

This theater required not just sophisticated professional acting, but required the actor to immediately sprinkle in jokes, maxims, complaints or philosophical treatises, rigidly “working out” the initially agreed upon “backbone” of the script.

The basis of the script was written in advance and discussed with the troupe members based on the planned audience. The performance, intended only for men, was a mixture of sparkling humor, satirical dialogue, crude slapstick, acrobatic stunts, hoaxes, clowning, music and sometimes dance. All this pushed into the background the main topic: the love of one or more young couples.

Intricate love conflicts were brought to the fore only with a female audience in mind.

By the 19th century, commedia dell'arte was becoming obsolete, but was continued in pantomime and melodrama. In the 20th century comedy serves as a model for the synthetic theater of Meyerhold and Vakhtangov, as well as the French Jacques Copeau and Jean-Louis Barrault, who revived the expressiveness of stage gesture and improvisation and attached great importance to ensemble acting.

Commedia dell'arte was born from carnival celebrations. There was no theater yet, but there were jesters, mimes, and masks. Another factor was the emergence of national Italian drama. New plays were written by Ariosto, Machiavelli, Bibiena, Aretino, but all these works are not suitable for the stage; they are oversaturated with characters and an abundance of plot lines. This dramaturgy was called “scientific comedy” (Italian: Commedia erudita).

Principle tipi fissi, in which the same characters (masks) participate in scenarios with different contents, is today widely used in the creation of comedy television series, and the art of improvisation is used in stand-up comedy.

Geiger Richard (1870-1945) "Pierrot and Columbine"

In the ancient Roman theater there was a type of folk performance called atellans. These were obscene farces, originally improvised, in which the actors also wore masks; Some of the characters were similar in the nature of the mask to the characters of the commedia dell'arte (for example, the Roman mask of Papus and the Italian mask of Pantalone), although it is wrong to talk about the Atellans as the predecessor of the commedia dell'arte: the gap in tradition between them is more than twelve centuries. Most likely, we can only talk about the similarity of circumstances in which these types of theater were born.

The characters of the Roman comedy, reinterpreted under the influence of national customs and morals, became the prototypes of the main characters: the gullible old Venetian merchant Pantalone; the pedantic Doctor of the University of Bologna; the braggart and coward Captain, who was easily recognized as an officer of the hated occupying Spanish army. Due to the mixture of such heterogeneous elements, it was impossible to build a single action, and the commedia dell'arte is a series of interludes.

Ludovic Alleamu “Saddled Pierrot”

Angelo Beolco (Rudzante) in the first half of the 16th century composed plays for the Venetian carnivals, using the technique of “learned comedy”. The confusing plots were accompanied by tricks and healthy peasant humor. A small troupe gradually gathered around Beolko, where the principle tipi fissi and the use of folk dialect speech on the theatrical stage became established. Finally, Beolko introduced dance and music into the dramatic action. This was not yet a commedia dell'arte - Beolko's troupe played within the framework given plot, she did not have free play and improvisation - however, the road for the emergence comedy was open. The first mention of the mask theater dates back to 1555.

Angelo Beolco(Italian Angelo Beolco, stage name - Ruzante (Italian Ruzzante); 1502, Padua, - March 17, 1542, Padua) - Italian playwright and actor

Angelo Beolco was illegitimate son a wealthy businessman who owned lands in the vicinity of Padua and had the academic degrees of Doctor of Arts and Doctor of Medicine. Raised in a family equal to legitimate children, Angelo received a good education, however, Beolko had no rights to the inheritance, and need forced him to enter the theater stage.

At the age of 18, Beolko organized an amateur troupe in Padua, which gave performances during carnivals, and composed for this troupe, always in the Paduan dialect, small scenes from the Paduan village life that was well known to him - buffoonish, comedic and even tragic, ending in murder.

The actors of Beolko's troupe performed under constant names and in unchanged costumes - Beolko called them unchanged types (tipi fissi), although the nature of the role could change depending on the genre. Beolko himself created the image of a cheerful and broken peasant guy from the outskirts of Padua - Ruzante, who knew how to sing and dance well.

In different plays, Ruzante could be a deceived husband, a stupid servant or a boastful warrior, but his character remained constant, and this constancy was emphasized by his constant peasant costume.

Success came very quickly, and Beolko found rich patrons, primarily in the person of the Venetian patrician, generous philanthropist Alvise Cornaro. The troupe performed exclusively in front of audiences belonging to the patrician or bourgeois class, and adapted to the tastes that prevailed in these circles.

Submitting to demand, Beolko began to write large plays - in the genre of “scientific comedy” (commedia erudita), widespread at that time, but, unlike most playwrights who worked in this genre, who were poorly familiar with the laws of theater and intended their works more likely for reading, Beolko wrote comedies exclusively for the stage, with certain actors in mind. Since the actors of his troupe went through a good realistic school, Beolko’s “learned comedies” were distinguished by their realistic depiction of people and everyday life.

Like all theater groups At that time, Beolko's troupe was semi-professional: it worked a lot during carnivals and much less during other periods; When forced breaks arose in the troupe’s activities, the actors who composed it returned to their previous occupations.

Nevertheless, Beolko's theatrical activities had a significant influence on the development of Italian professional theater; his “unchanging types” anticipated the appearance of the “comedy of masks,” but there was no improvisation in the Beolko theater. In the Venetian Republic, Beolco found many followers - actor-playwrights, the most famous among them were Antonio da Molino, nicknamed Burchiella, and Andrea Calmo.

At least some comedies written by Beolko are known: “Coquette”, “Comedy without a title”, “Flora”, “Ankonitanka”, “Dialogues in a rude peasant language”, “The funniest and funniest dialogue” - and two more, representing reworkings of Plautus’ comedies: “Cow” and “Pyovana”.

Beolko's comedies were distinguished by a rare realism for that time in depicting the life and customs of the Paduan peasants; his satire avoided the mockery characteristic of the “peasant farces” of the Renaissance.

Forced to take into account the tastes of his audience, Beolko nevertheless, wherever he could, rejected the established canons and in the prologue of one of his comedies, made up as Plautus, he argued that writing comedies the way Plautus and other ancient playwrights wrote them was already impossible: if Plautus had lived, he would have written completely differently.

Beolko did not have time to carry out the reform of comedy and, as a playwright, did not find a worthy successor, which, however, did not prevent his contemporaries from appreciating the merits of his comedies; yes, famous literary critic Benedetto Varchi wrote that "the comedies of Ruzante of Padua, representing rustic subjects, are superior to the ancient Atellans."

Auguste Toulmouche (1829 - 1890)

Zanni(Italian Zanni) - large group servant characters (masks) of the Italian commedia dell'arte, among which the most important are: Brighella (the first zanni of the Venetian quartet of masks), Harlequin (the second zanni of the Venetian quartet of masks), Coviello (the first zanni of the Neapolitan quartet of masks) and Pulcinella (the second zanni of the Neapolitan quartet of masks ). This also includes girls, maids Columbina, Fantesca, Smeraldina, etc.

The word "zanni" comes from the name "Gianni" (Italian: Gianni) in Venetian pronunciation. Zan Ganassa was the name of one of the first actors who made this mask famous.

Zanni on the stage of the square theater there are some of the oldest masks, continuing the tradition of court and carnival jesters. They appear in Italian farces of the 15th century, and even earlier - on the pages of Renaissance short stories.

Zanni- these are servants, former peasants who left their native places due to poverty and unemployment (Bergamo for the northern masks, Cava and Acerra for the southern ones) in search of better life in prosperous port cities (Venice in northern Italy and Naples in the south). The townspeople looked at the newcomers with mockery and willingly laughed at them.

They often portray them as completely stupid (Harlequin), or smart, but with provincial actions unusual for a city dweller (Brigella), with a dialect characteristic of “hillbillies” (Harlequin and Brigella, for example, speak a rather monosyllabic Bergamascan dialect of Italian). Over time, of course, this satire softened, especially since it is the zanni who actively intrigue the script, helping the lovers in their confrontation with the old men Pantalone and the Doctor.

Begma Oksana “Pierrot flirts with Columbine”

Brighella(Italian Brighella, fr. Briguelle) - mask character of the Italian Commedia dell'Arte, the first zanni; one of the most ancient servant characters of the Italian theater. Represents the Northern (or Venetian) quartet of masks, along with Harlequin, Pantalone and Doctor.

Brighella is a former peasant, a native of Bergamo, who speaks the abrupt, monosyllabic, ending-eating Bergamo dialect. He hires himself out as a servant, cheats, and delights with witticisms and risky jokes.

Brighella wears a linen blouse, long trousers, a cloak and a white cap. His suit is white, usually trimmed with green braid. The costume is completed with yellow leather boots. There is a black pouch at the belt, and a dagger (sometimes wooden, but more often real) behind the belt.

Brighella's mask is hairy, dark in color with a black mustache and a black beard sticking out in all directions.

This is a clever and resourceful fellow, often a thieving servant; cheeky with women, insolent with old people, brave with cowards, but helpful to the strong; always loud and talkative. At first angry and ruthless, by the 18th century. Brighella becomes softer and more cheerful.

His philosophy is very reminiscent of Bozena Rynska’s public statements: Brighella amuses the audience with long monologues against the old people who prevent the young from living, loving and achieving happiness. They vote incorrectly in elections, cross the road in the wrong place, and make up 71% of the completely unnecessary population, as the Vice-Rector of the Higher School of Economics recently noted.

In our country this is already becoming the norm, almost a “fashionable trend” among the “enlightened elite”. Previously, this was generally considered business card stupid hillbilly.

The actors playing this mask are required to be able to play the guitar and master basic acrobatic tricks.

|

|

|

Scapino, drawing by Maurice Sand, 1860 |

Brighella's mask, although it was one of the most beloved by ordinary spectators, as a rule, was in the background of intrigue; The lack of active action was compensated by a large number of insert tricks ( Lazzi) and musical interludes. Images close to Brighella are present in the comedies of Lope de Vega and Shakespeare; these are also Scapin, Mascarille and Sganarelle by Moliere and Figaro by Beaumarchais.

The most famous performers This role included Nicolo Barbieri, who performed under the name Beltrame, Carlo Cantu (Buffetto) and Francesco Gabrielli (Scapino).

To be continued…

from the book "Western European theater from the Renaissance to the turn of the 19th-20th centuries.", M., 2001

M. Davydova. Commedia dell'arte

Humanistic theater is a theater where learned people play for learned people; it is a rather artificial formation, prompted not by life, but by the humanists’ own speculative ideas. But during the Renaissance, a grassroots folk genre also appeared in the theatrical culture of Italy, which was actually born thanks to the division between humanistic and folk cultures. However, this genre was successful not only among ordinary people, but also among humanist scientists.

The names of Harlequin, Pierrot or Columbine are known to everyone, but few people know that these heroes of the folk theater have their prototypes in the characters of the commedia dell'arte, a theatrical genre that formed in Italy in the second half of the 16th century. Its main feature was the presence of permanent types, “masks”. In this case, a “mask” is understood not only as a special device worn on the face (although many characters in the commedia dell’arte actually wore such masks), but also a certain socio-psychological type: an arrogant ignorant, a broken servant, an amorous old man, etc. Each of these characters had a specific costume and a constant set of stage techniques - characteristic expressions, gestures, poses. An actor in a commedia dell'arte played the same role all his life, the same character in different proposed circumstances. He could go on stage from a young age in the image of old Pantalone or play the young and perky Brigella until his old age.

Firmly fixed dramatic text there was no commedia dell'arte. There were scenarios that were just an outline of the main events. The script page was pinned to the backstage wall so that the actors could know what would happen in the next scene before going on stage. An idea of commedia dell'arte scripts is given by the first collection that has come down to us (1611), compiled by Flamineo Scala, the leader of the most famous troupe "Gelosi". Following it, several more collections were published. Unfortunately, we have almost no earliest short scripts that could fit on a piece of paper. They reached a later literary adaptation. Moreover, by the end of the 17th century. they began to approach literary drama. The scripts were very different. 99 percent were comedies, but there were also tragedies and pastorals. For example, in the tragedy of Nero, along with Seneca and Agrippina, Brighella and other masks acted. (By the way, it was the Gelosi troupe that first performed Tasso’s pastoral “Aminta” at the summer residence of the Dukes of Este, on the islet Belvedere in the middle of the Po River. The role of Sylvia was played by the best actress of the troupe, the incomparable Isabella Andreini.)

The script, we repeat, was only an outline of the main events. The absence of texts led to another feature of the commedia dell'arte - improvisation. The actors had to come up with the text on the fly in accordance with the character and psychological characteristics that “mask” that became their stage alter ego.

Improvisation is a product of carnival. It did not exist in the medieval theater and the theater of scientific comedy. Partnership and communication arose precisely in commedia dell'arte. It is easy to understand that participation in such performances required immeasurably more professionalism from the actors than academic drama. Commedia dell'arte actually became the first form of professional European theater. He had a huge influence on Lope de Vega, Shakespeare, Moliere (the latter even took acting lessons from Italian comedians). The very name “commedia dell’arte” contains a contrast to the Renaissance “scientific” theater, which, as we have already said, was amateur. La commedia - in Italian, not only “comedy” in our sense, but also theater in general, a spectacle; arte is an art, but also a craft, a profession. In other words, we're talking about about a spectacle performed by professionals.

Semi-professional troupes began to appear in Italy (especially in Venice) already at the beginning of the 16th century. Mainly artisans took part in them. The Venetian patricians willingly invited them to their home celebrations, where they performed the comedies of Plautus and Ternetius, eclogues, farces and momarias - musical pantomimes in masks. Most of the members of these communities, at the end of the “theater season,” returned to their original professions: carpentry, carpentry, and boot making. However, the most talented of them made acting their main profession.

A special role in the development of semi-professional theater was played by Angelo Beolco from Padua (1502-1542) - the author of comedies and farces from peasant life, in which he interspersed motifs from the comedies of Plautus. Beolko received a good education and was well acquainted with classical drama, but, unlike the authors of academic drama, who wrote plays in the quiet of their offices, he began performing on stage from a young age. Beolko gathered around himself a troupe of amateurs. The activities of this troupe were marked by two important features that allow us to call Beolko and his comrades the direct predecessors of the commedia dell'arte. Firstly, unlike the pastoral peasants, who spoke in refined language, the peasants in Beolko's farces and comedies spoke the Paduan dialect. (The use of dialects, which, due to the fragmentation of Italy, acquired particular stability, would later become a characteristic feature of the commedia dell'arte and one of the main sources of comedy.) Secondly, the actors from Beolko's troupe performed with constant stage names and in constant costumes. Beolko himself chose the role of the broken country boy Ruzante.

Beolco was the direct predecessor of the commedia dell'arte, but its real birth occurred about 20 years after his death. In 1560, a performance of commedia dell'arte was documented in Florence, in 1566 - in Manua, and in 1568 in Munich, on the occasion of the wedding of the Crown Prince, an improvised comedy with masks was performed by Italians living in Bavaria. The Munich performance was described by a humanist writer. There is evidence that the audience was dying of laughter.

Around the same time, the most famous commedia dell'arte troupe in Europe, Gelosi (The Zealous), arose. This troupe, consisting of 12-15 people, assembled a brilliant galaxy of actors. Its true adornment was the famous European actress and poetess, the legendary beauty Isabella Andreini. The King of France himself Henry III, captivated by the performance of the troupe, invited the actors to Paris. It is interesting to trace how not only the status, but primarily the self-awareness of the actors changes during these years. In 1634, a book by one of the most educated actors of the commedia dell'arte, Nicolo Barbieri, "A Request addressed to those who speak in writing or orally about actors, neglecting their merits in artistic matters," was published. In it, Barbieri, trying to get rid of the actor's inferiority complex, writes: "The goal of the actor is to bring benefit by amusing."

Italian artists have repeatedly emphasized their special position among their brothers. Comparing the Italian and French artists, Isabella Andreini wrote that the Frenchman is made of the same material, “from which parrots are made, who can only say what they are forced to repeat by heart. How much higher than them is the Italian... who, in contrast to the Frenchman, can be compared to a nightingale, composing their trills in a momentary whim of the mood." The Italian actor was also a synthetic actor, that is, he knew how not only to improvise, but also to sing, dance and even perform acrobatic stunts. The fact is that the performance of the commedia dell'arte was a multi-part action. The main plot was preceded by a prologue in which two actors with a trumpet and a drum invited the audience, advertising the troupe. Then an actor appeared, outlining the essence of the performance in verse. Then all the actors poured out and “shari-vari” began, during which the actors demonstrated their skills in every way: “This is what we can do, and we can do everything.” After this, the actor and actress sang and danced. And only then did they begin to play out the plot.

The comic peak of the commedia dell'arte was lactation, buffoonery tricks that had nothing to do with the action and were played by zanni servants. After the completion of the plot, farewell to the public began, accompanied by dancing and songs. One of the actors wrote then that the dead are happy, lying underground, where grief and death reign, “but we do not have the strength to grieve our sorrows, let’s laugh at them.” The essence of the commedia dell'arte was "l"anima allegre" - "joyful soul".

By the time of the activity of "Gelosi", the gaming canon of commedia dell'arte had obviously already taken shape. Formed in common features oh and the most popular masks.

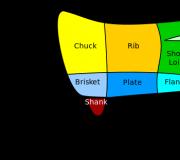

Commedia dell'Arte masks

Commedia dell'arte had two main centers: Venice and Naples. In accordance with this, two main quartets of masks emerged: northern, or Venetian (Pantalone, Harlequin, Brighella, Doctor) and southern, or Neapolitan (Tartaglia, Scaramuccio, Coviello, Pulcinello). The Captain, Fantesca (or Servette), and the Lovers often took part in both quartets. In general, the number of masks that appeared on the stage of commedia dell'arte over the two centuries of its existence exceeds a hundred. But they were all modifications of the basic masks listed above.

Commedia dell'arte masks can be divided not only into northern and southern quartets, but also into functional groups. The first is satirical masks (old people). The second is comedy (servants). The third is lovers.

Old men

Pantalone is a rich and stingy Venetian merchant. Previously, when Venice was an intermediary in trade between the East and Europe, Venetian merchants were majestic and almost heroic figures. They ruled the seas, established trade relations with Byzantium, and paved the way into the depths of Asia. With the fall of Constantinople and the opening of routes to India across the ocean, Venice loses its trading power. The Venetian merchants become pathetic figures, but do not want to give up their vain claims to greatness, which is why they find themselves the subject of ridicule.

Pantalone is an image of decrepitude not only social, but also physical. He embodies the life of the senile body in all its ugly details. It’s as if he collects all the ailments: lameness, shortness of breath, senile insanity. Pantalone is not only stingy and arrogant, he is also amorous and usually acts as a rival to his own son. To prove to his young bride that he is still somewhere, Pantalone often starts dancing, during which he is seized by an attack of gout. For all his unusual activity, Pantalone is an extremely pathetic and suffering figure. Every now and then he is deceived and ruined.

Pantalone's costume was made up of the everyday attire of Venetian merchants: a red jacket, red narrow trousers, a long black cloak (cape). The performer of the role of Pantalone wore a black mask, a hooked nose, and a wedge-shaped beard. The main features of Pantalone's image were created by the actor of the Gelosi troupe, Giulio Pasquati.

Another image of a satirical old man is the Doctor. This is rarely a doctor (in this case he appears on stage with an enema), usually he is a doctor of law, a lawyer from the University of Bologna. Why does a lawyer from Bologna suddenly turn out to be a comic mask? The University of Bologna was the oldest in Europe. It was his professors who discovered and commented on Roman ancient jurisprudence (the “Code of Justinian”) and did a lot for the development of European jurisprudence. However, gradually they degenerated into dogmatists. In the era of the Late Renaissance, these are pedants, scribblers and bores, filled with the deepest reverence for their own erudition. The smug Doctor constantly utters truisms, utters pompous maxims, sprinkles Latin quotes and compares everything with antiquity. At the same time, monstrous confusion reigns in his head. The doctor is a classic example of a monologue person; he doesn’t care how interested his interlocutor is in his tirades: just to talk. His speech is structured like this: the first phrase is logically connected with the second, the second with the first, but the first with the third are in no way connected. For example: “Florence is the capital of Tuscany; red speech was born in Tuscany; the king of red speech was Cicero; Cicero was a senator in Rome; there were twelve Caesars in Rome; there are twelve months in a year,” etc. The doctor wore a black robe, hat, a white collar, a code of laws under his arm, a pen behind his ear, an inkwell on his neck, a mask on his face. The main features of the Doctor's mask were outlined by Lodovico di Bianchi ("Gelosi").

In the quartet of southern, Neapolitan masks there was no old man parallel to the northern Pantalone or the Doctor. This gap was filled, in a sense, by Tartaglia's mask. Tartaglia is a satire on Spanish servants. This is an elderly man in a green, official-style suit, huge glasses and with a briefcase under his arm. Tartaglia means stutterer in Italian. Involuntary and obscene puns come out of his mouth every now and then. The hero's stuttering turns into a kind of birth pangs, and Harlequin, acting as a midwife, butts him in the stomach.

And Pantalone, and the Doctor, and Tartaglia are a comic fixation of those socio-psychological types that have experienced their heyday and are now declining.

Another mask that captures a social type that is becoming a thing of the past and, in this sense, is adjacent to the satirical masks of old people is the Captain. The image of the Captain goes back to the character from “The Boastful Warrior” by Plautus Pigropolynik ( literal translation of this name - Tower-Conqueror). This is a cowardly braggart and a cruel warrior, who in the end is inevitably put to shame. He runs away from Harlequin's beaters and is even frightened by Pantalone's threats. The Captain's own names were supposed to inspire fear. For example, Matamoros (Killer of the Moors) or Fracassa (Roar). One of the creators of the Captain mask, Francesco Andreini, Isabella's husband and the head of Gelosi, became famous under the name of Captain Spavento (Horror). He collected the terrifying tirades of his hero in a book, which was published under the title “The Boasts of Captain Spavento.” Among them is the following: “I am Captain Terror from the Valley of Hell... the greatest killer, tamer and ruler of the universe, son of earthquake and lightning, relative of death and bosom friend of the great hellish devil.”

The image of the Captain was not only literary prototype. Such “characters” were also found in real life. The fact is that, like Tartaglia, the Captain from the Commedia del Arte is Spanish by origin. His speech is replete with Spanish words, and his suit is cut reminiscent of Spanish military attire. In the 16th century Spain conquered all of southern Italy and encroached on northern Italy, and the image of the Captain is the revenge of the Italians on the Spaniards, a mockery of Spanish arrogance and cowardice. At the same time, the middle of the 16th century. - the beginning of the decline of a powerful empire. The Captain's time is irrevocably gone. He boasts of his military exploits, but his sword is firmly soldered to the scabbard and entangled in cobwebs.

Over the years, the figure of the Spanish Captain has become less and less relevant for Italy. Various stylizations of this mask appear. One of them is the character of the southern quartet Scaramuccio. Its creator, the Neapolitan comedian Tiberio Fiorilli, gained particular fame in France (it was from him that Moliere took stage lessons). The captain did not wear a mask at all, and Scaramuccio whitened his face with chalk, which made it possible to emphasize his incomparable facial expressions. He removed everything that pointed to the Captain's military profession, turning him into a social braggart. Fiorilli became especially famous for his lazzi.

Servants

Buffoonery in the commedia dell'arte performance system usually fell to the lot of the most popular and beloved by the audience masks of the zanni servants. In Italy, servants very often became peasants who did not have any special knowledge, who went in droves to the city from an impoverished village. In Venice, these are usually peasants from Bergamo. Zanni is a derivative of Giovanni, a nickname parodying the Bergamo dialect. The Venetians considered the mountain Bergamians to be swindlers, and the lowland Bergamians to be fools. In accordance with this idea, two types of zanni arose. The first is a rogue and adventurer, quickly adapting to the conditions of city life and turning into a savvy lackey. The second is slow-witted and a klutz, always getting into trouble. They formed a comic unity, complementing each other. The first "dynamic" zanni confused the intrigue thanks to energy and ingenuity, the second, "static" - due to stupidity and sluggishness. In the north, the most famous zanni were the rogue Brighella and the simpleton Harlequin.

In the plot of the commedia dell'arte, Brighella is the mainspring of intrigue. He is a pragmatist and a cynic and will stop at nothing to achieve his goal. Brighella is not only energetic, but also extremely talkative, and explains this by the muteness of his father, who bequeathed to him an unspent capital of speeches. Every now and then he gives birth to doubtful moral sense aphorisms. He even has his own philosophy of theft: to steal, he claims, means to find it before you lose it. Brighella wore white linen peasant clothes with a green or yellow braid (the emblem of his official position), a dagger and a leather pouch at his belt, as well as a dark-colored mask with a black mustache and a black beard sticking out in all directions.

In contrast to Brighella, Harlequin is simple-minded, childishly helpless and often receives beatings, but at the same time never loses his presence of mind. He is poor, and his white blouse is covered in multi-colored patches, and on his cap hare's foot-symbol of cowardice. There is a hypothesis that Harlequin originated from Ellekin, the mystical devil (his name first appeared in French infernal legends). It is clear that there is a huge distance between the unlucky servant and the devil, but Harlequin still retained something from his ancestor. For example, a bump on the forehead, the remnant of a devil's horn. The first actor who gave this name to the mask of the second zanni was Tristan Martinelli, who toured in France. The most famous Harlequin was Domenico Biancolelli (1618-1688), who also made a career outside Italy, mainly in France. Biancolelli changed both the character of Harlequin and his costume. From the second “passive” zanni, he turned him into an active, resourceful and malicious intriguer, and poor clothes with numerous patches into an aesthetically stylized leotard, consisting of regular multi-colored triangles closely adjacent to each other. This is how the Harlequin costume, familiar to all of us, turned out from peasant attire. The Harlequin Mask has long survived the commedia dell'arte. Two centuries later, on the basis of French theatrical culture, he will turn into a happy rival of Pierrot, a passive and suffering figure, or more precisely, into the lover of his wife Columbine.

In the south, the most popular zanni were the evil rogue with a long bird's nose, Coviello (the southern parallel of Brighella), and Pulcinella, who gained all-European fame. Northern zanni are generally bachelors. In the south, due to the lack of masks of old people, Pulcinelle acted as a deceived husband. He is grotesquely ugly. He has a belly in front, a large hump in the back, a mask on his face with a large hooked nose, he speaks in a nasal voice. The character of this hero underwent the most unexpected transformations. He is sometimes stupid, sometimes sly, sometimes sarcastic. He is usually a servant, but can also be a shepherd or a bandit. The many-sided Pulcinello soon became the hero of special performances on the topic of the day - pulcinella, performed either by puppets or by live actors. Pulcinello stood at the origins of the English Punch, the French Polichinelle and the Russian Petrushka.

The female parallel of the zanni was a phantesque servant who bore a wide variety of names: Smeraldina, Franceschina, Columbina (it was this name that survived in modern pantomime along with the names of Harlequin and Pierrot). The fantes are usually looked after by old men and servants, but only the first zanni is successful. At first, the fantasy is a simple peasant girl, always getting into trouble, a kind of Harlequin in a skirt. This is how the actress of the Gelosi troupe, Silvia Roncagli, brought her to the stage under the name Franceschina from Bergamo. Later, already on French soil, the mask is transformed from a village fool into an elegant maid Columbine, and her peasant clothes turn into an elegant soubrette costume. The most famous Colombina was Catherine Biancolelli, daughter of Domenico.

Lovers

The lovers were closest to the heroes literary drama. They were played only by young actors and actresses. The role of the first lover was often played by the director of the troupe, who is also the author of the scripts. In "Gelosi" he was Flamineo Scala (stage name - Flavio). The most famous of the actresses in this role was the already mentioned Isabella Andreini. Unlike servants and satirical old men, the lovers did not wear masks, dressed fashionably and luxuriously, spoke the Tuscan dialect (Petrarch wrote his sonnets in it) and refined plastic arts. They were the first to abandon improvisation and write down the text of their roles in books. Their manneristically pompous speeches can be classified not as literature, but rather as literary. If there were two pairs of lovers in the troupe, then they were divided, just like zanni, into “dynamic”, i.e. energetic, inventive, witty, and “static” - timid, gentle and sensitive. It should be said that, despite the poetry, lyricism and grace of manners, the actors playing the roles of lovers almost always maintained an ironic distance in relation to their characters. In their very excessive, almost grotesque sophistication, one could feel the laughter of the commedia dell'arte. Two old men, two pairs of lovers, more old men as grooms or lawyers, doctors, etc., a pair of servants in love, a zanni, together with a fantasy, exhausted the entire necessary composition of masks.

When theater historians began to study the masks and plots of the commedia dell'arte, they noticed that all this was similar to the Dorian farce (a skit with primitive comic types), which had developed long before the birth of ancient Attic comedy, and atellana, theatrical genre, formed in Ancient Rome in the 3rd century. BC. (his characteristic features also included the presence of permanent mask types and the absence of a fixed dramatic text). A version has emerged that the Italian commedia dell'arte is the revived Roman atellana. It would be more correct, however, to speak not about direct continuity, but about the fact that all these genres grow from the depths of an archaic folk spectacle, the aesthetic language of which is similar and uniform throughout the entire theatrical tradition.

The archaic (or primitive) type of thinking is distinguished by an organically holistic perception of life in the integral unity of above and below, death and resurrection. Time for archaic consciousness does not move linearly, but in a circle, like the change of seasons (this is the cyclical time of myth, not history). Man does not completely isolate himself from the endless world of becoming, and certainly does not oppose himself to it.

The principles of archaic thinking are clearly discernible in the carnival culture of the Middle Ages, closely associated with the beliefs of barbarian peoples, with its concept of a “grotesque body” perceived as a cosmos, when the whole world turns out to be like a single grandiose organism, endlessly renewing and growing. Death and birth, up and down are related and connected here.

The idea of circular movement, its endless repetition, which lies at the basis of the archaic worldview, can only give rise to stable plot blocks with constant types and masks. Thus, from the fescennina (ritual agricultural games) in Rome, atellana is born, and from the Western European carnival comes the commedia dell'arte. For such theatrical forms there is no need for a rigidly fixed dramatic text, because they play out eternal (repeated) plots.

In contrast to the archaic system of worldview, Christianity opens up unilinear time. Christian myth is a one-way drama from the Fall through the climax (crucifixion) to the finale (the second coming and Last Judgment). The concept of linear time becomes the basis on which a rationalistic type of worldview is born in Western European culture, transforming the world into a continuous and visible order. The Renaissance is “the last myth of man,” but at the same time it is an important milestone in rationalistic knowledge based on the Christian and Hellenistic traditions. A person no longer feels like an organic part of the endless process of birth and dying, but is fully aware of himself as a person confronting the world and interacting with it. Commedia dell'arte, as we have already said, grows out of the depths of an archaic folk spectacle. At the same time, being formed in the era of the Late Renaissance, it turns out to be closely connected with late Renaissance literature and life. Moreover, upon careful examination, such sharply opposed genres as scientific comedy and commedia dell'arte reveal a number of common features (for example, the presence of constant types). By the way, the source of plots in commedia dell'arte was originally scientific comedy. The scheme of these plots is canonical: young people love each other, old people interfere with them, servants help them overcome obstacles.

Here we need to make a small digression and clarify a number of fundamental points. Learned comedy was guided, as is known, by examples of Roman comedy (Plautus, Terence), but the latter in turn (especially Plautus) was strongly influenced by atellana, a genre related to commedia dell'arte. It turns out to be a kind of vicious circle and the question arises: where is the watershed separating the genres growing out of archaic folk spectacle from Roman and Italian comedy. The presence in the latter of a strictly fixed dramatic text is, of course, a fundamental difference, but not the only one. Another thing is no less important. The archaic folk spectacle is not oriented towards any models; it is born spontaneously and organically, there is absolutely no moment of reflection in it. Plautus consciously uses elements of the old theatrical tradition, he manipulates them. Italian comedy comes to eternal plots and permanent mask types indirectly through the plays of Roman comedians. She feels like a successor to ancient dramatic models, and no longer images of folk theatrical culture, but types and plot twists Plautus himself becomes the subject of manipulation. The moment of reflection is revealed here to the maximum.

In this sense, commedia dell'arte finds itself in an ambivalent position. Its formation does not precede the emergence of scientific drama, which would be logical, but follows it and is influenced by it. Therefore, in the poetics, the sum of the theatrical techniques of the commedia dell'arte, one can see the interaction of different forms of worldview, different cultural layers. The folk carnival is fully manifested where the plot ends - in lazzi, in which elements of archaic folk fun and carnival comedy are clearly visible. The mask, in its aesthetics, also belongs to the carnival mockery of man’s equality with himself.

At the same time, the commedia dell'arte mask cannot be entirely attributed to carnival culture. In it (especially in the images of old people) the satirical element is very strong, and satire is a property of modern times, fixing the certainty of the world and the human personality, their equality with themselves. The masks of Atellana or Dorian farce are nothing more than “eternal types”; in commedia dell’arte they are always socially charged. Not just an amorous miser, but a Venetian merchant, not just a learned pedant, but a lawyer at the University of Bologna. The mask of commedia dell'arte came to the rescue when it was necessary to consolidate the social change in consciousness. This, to use Marx’s words, is a form of cheerful, painless farewell to the past. It naturally arises during the Renaissance, the greatest revolution, when European history is experiencing a chain of social upheavals. A mask as a means for an individual to stop being himself for a while is part of carnival culture. The mask, understood as a social theatrical type that records the past, turns out to be part of a new way of understanding the world.

The actor in the commedia dell'arte, as we could see, did not simply put on someone else's mask as at a carnival, but emphasized the difference between himself and the mask as the subject of the game. This ironic aesthetic distance between the creator and the created is the moment of reflection, which takes the commedia dell'arte far beyond the framework of the popular grassroots genre and makes it part of the Renaissance, or more precisely, post-Renaissance culture.

Masks of Venice. Commedia dell'arte masks

Commedia dell'arte (Italian: la commedia dell'arte), or comedy of masks - a type of Italian folk theater, performances of which were created using the method of improvisation, based on a script containing a brief plot outline of the performance, with the participation of actors dressed in masks. Various sources also refer to it as la commedia a soggetto (script theatre), la commedia all’improvviso (improvisation theatre) or la commedia degli zanni (zanni comedy).

The number of masks in commedia dell'arte is very large (there are more than a hundred of them in total), but most of them are related characters that differ only in names and minor details. The main characters of the comedy include two quartets of male masks, the Captain's mask, as well as characters who do not wear masks, these are the Zanni girls and the Lovers, as well as all the noble ladies and gentlemen.

Male characters

Northern (Venetian) quartet of masks:

- Pantalone (Magnifico, Cassandro, Uberto), - Venetian merchant, stingy old man;

- Doctor (Doctor Balandzone, Doctor Graziano), - pseudo-scientific doctor of law; old man;

- Brighella (Scapino, Buffetto), - the first zanni, an intelligent servant;

- Harlequin (Mezzetino, Truffaldino, Tabarino), - second zanni, stupid servant;

Southern (Neapolitan) quartet of masks:

- Tartaglia, the stuttering judge;

- Scaramuccia, a boastful warrior, a coward;

- Coviello, first zanni, intelligent servant;

- Pulcinella (Policinelle), second zanni, stupid servant;

The captain is a boastful warrior, a coward, the northern analogue of the Scaramucci mask;

- Pedrolino (Pierrot, Clown), servant, one of the zanni.

- Lelio (also Orazio, Lucio, Flavio, etc.), young lover;

Female characters

- Isabella (also Lucinda, Vittoria, etc.), young lover; often the heroine was named after the actress who played this role;

- Columbina, Fantesca, Fiametta, Smeraldina, etc., are maids.

ZANNI - Common name comedy servant. The name comes from the male name Giovanni, which was so popular among the common people that it became a common noun to designate a servant. The zanni class includes such characters as Arlecchino, Brighella, Pierino, who appeared later. The characteristics of the nameless zanni are an insatiable appetite and ignorance. He lives exclusively for today and does not think about complex matters. Usually loyal to its owner, but does not like discipline. At least 2 such characters took part in the play, one of whom was dull, and the other, on the contrary, was distinguished by a fox-like intelligence and dexterity. They were dressed simply - in a shapeless light blouse and trousers, usually made from flour sacks. The mask initially covered the entire face, so in order to communicate with other heroes of the zanni comedy, one had to lift its lower part (which was inconvenient). Subsequently, the mask was simplified, and it began to cover only the forehead, nose and cheeks. A characteristic feature of the zanni mask is the elongated nose, and its length is directly proportional to the stupidity of the character.

HARLEQUIN (Arlecchino) - zanni of the rich old man Pantalone. The Harlequin costume is bright and colorful: it is made up of diamonds of red, black, blue and green. This pattern symbolizes Harlequin's extreme poverty - his clothes seem to consist of countless poorly chosen patches. This character can neither read nor write, and by origin he is a peasant who left the impoverished village of Bergamo to go to work in prosperous Venice. By nature, Harlequin is an acrobat and a clown, so his clothes should not restrict his movements. The mischievous man carries a stick with him, which he often uses to bludgeon other characters.

Despite his penchant for fraud, Harlequin cannot be considered a scoundrel - a person just needs to live somehow. He is not particularly smart and is quite gluttonous (his love for food is sometimes stronger than his passion for Columbine, and his stupidity prevents the fulfillment of Pantalone’s amorous plans). Harlequin's mask was black, with ominous features (according to one version, the word “Harlequin” itself comes from the name of one of the demons of Dante’s “Hell” - Alicino). On his head was a white felt hat, sometimes with fox or rabbit fur.

Other names: Bagattino, Trufaldino, Tabarrino, Tortellino, Gradelino, Polpettino, Nespolino, Bertoldino, etc.

Columbina

- servant of the Lover (Inamorata). She helps her mistress in matters of the heart, deftly manipulating the other characters, who are often not indifferent to her. Columbine is distinguished by coquetry, feminine insight, charm and dubious virtue. She is dressed, like her constant boyfriend Harlequin, in stylized colored patches, as befits a poor girl from the provinces. Columbine's head is decorated with a white hat, matching the color of her apron. She doesn’t have a mask, but her face is heavily made up, her eyes are especially brightly lined.

Other names: Harlequin, Corallina, Ricciolina, Camilla, Lisette.

PEDROLINO or PIERINO (Pedrolino, Pierino)

- one of the servant characters. Pedrolino is dressed in a loose white tunic with huge buttons and too long sleeves, a round ribbed collar on his neck, and a cap hat with a narrow round crown on his head. Sometimes the clothes had large pockets filled with souvenirs romantic in nature. His face is always heavily whitened and painted, so there is no need to wear a mask. Despite the fact that Pedrolino belongs to the Zanni tribe, his character is radically different from that of Harlequin or Brighella. He is sentimental, amorous (although he suffers mainly from soubrette), trusting and devoted to his owner. The poor guy usually suffers from unrequited love to Columbine and from the ridicule of other comedians, whose mental organization is not so subtle.

The role of Pierino in the troupe was often played by the youngest son, because this hero was obliged to look young and fresh.

BRIGELLA - another zanni, partner of Harlequin. In a number of cases, Brighella is a self-made man who started without a penny, but gradually accumulated money and secured a fairly comfortable existence for himself. He is often depicted as a tavern owner. Brighella is a big money lover and a ladies' man. It was these two emotions - primitive lust and greed - that froze on his green half mask. In some productions, he appears as a servant, more cruel in character than his younger brother Harlequin. Brighella knows how to please her master, but at the same time she is quite capable of deceiving him, not without benefit for herself. He is cunning, cunning and can, depending on circumstances, be anyone - a soldier, a sailor and even a thief.

His costume is a white camisole and trousers of the same color, decorated with transverse green stripes. He often carries a guitar with him, as he is inclined to play music.

Brighella's mask, although it was one of the most beloved by ordinary spectators, as a rule, was in the background of intrigue; the lack of active action was compensated by a large number of insert tricks and musical interludes. Images close to Brighella are present in the comedies of Lope de Vega and Shakespeare; these are also Scapin, Mascarille and Sganarelle by Moliere and Figaro by Beaumarchais.

LOVERS (Inamorati)