The culture of the ancient Sumerians is characterized. Habitat and features of Sumerian culture

In the development of astronomy and astrology, a special place belongs to the Sumerians and Babylonians. The world learned about the Sumerians and their highly developed culture in the 19th century - thanks to archaeological excavations that discovered hundreds of thousands of clay “manuscripts” in the ruins of the library of Ashurbanipal (668-626 BC), consisting of both new records and from copies of texts from earlier times.

All significant temples regularly sent reports to the king with an interpretation of what happened in heaven. The library of Ashurbanipal served as a kind of scientific center, where these reports were concentrated.

At the end of the 19th century. French archaeologists discovered a huge archive of economic documents of the ancient Sumerian city of Lagash with income and expenditure records, plans of land plots with size indications and calculation of areas. This archive is very interesting to study social history Sumerians.

No less important for the history of architecture, mathematics and astronomy were the cuneiform tablets from the library at the Temple of Enlil in Nippur. The library occupied more than 80 rooms. School premises were also discovered near the temple, where teaching aids and texts to exercise students in writing, grammar, mathematics and astronomy.

The deciphering and reading of ancient texts became the sensation of the century and shed light on a forgotten era of human culture five thousand years ago. It became known that Mesopotamia was inhabited by Sumerians in the south and Akkadians in the north. In the 3rd millennium BC. e. Sumerian large cities in the south (near the Sea of Eridu, on the border with the desert of Ur, Nippur, Lagash, Uruk, Larsa) reached their peak. They were not isolated from the ancient civilizations of Mohenjo-Daro in the east and Egypt in the west; trade and economic contacts existed between them.

IN northern cities In Mesopotamia (Babylon, Agada, Sitara, Borsippa), the Akkadians adopted the culture of the Sumerians. Around 2500 BC e. The Akkadians took possession of the entire country. At this time, the military forces consisted of Akkadians, while the Sumerians were the scribes, government officials and temple priests. The dominant position in the next century returned to the south: the rulers of Ur and Lagash called themselves “kings of Sumer and Akkad.” Subsequently, Babylon becomes the capital and cultural and economic center of the country.

S. N. Kramer, based on studies of cuneiform manuscripts, in his book “History Begins in Sumer”, highlighted such issues of the cultural history of ancient class society as education, international relationships, political system, social reforms, codes of laws, justice, medicine, Agriculture, natural philosophy, ethics, religious views: heaven, flood, the first legend of the resurrection from the dead, the other world, epic literature- tales of Gilgamesh.

A simple listing of the questions raised by Kramer about the history of Sumerian culture testifies to the breadth and depth of the author's research.

The Sumerians made great contributions to humanity in the development of mathematics and astronomy. Sumerian mathematical culture was multinational: it developed through cultural communication and international overseas trade with Egypt and India (Mohenjo-Daro), whose social and cultural development was on a par with Sumer.

Astronomical science also developed in the fertile valleys of the Indus, Nile, Tigris and Euphrates rivers. These valleys have different natural and geographical conditions, and rivers behave differently. However, they are united by a very significant factor - the absence of precipitation for many months of the year. Because of this, at the dawn of sedentary agricultural culture, grain growers used river floods and artificial irrigation of the soil. The beginning of agricultural work depended on the time of melting of snow in the mountains, the time of river flooding, on the timely annual cleaning of canals and irrigation networks from sediments amounting to many thousands of cubic meters of silt, on the construction and repair of dams, on the organization of the correct and timely distribution of water in the irrigation network.

Heterogeneous agricultural work had to be carried out in a certain sequence throughout the year, being interconnected throughout the entire irrigated valley. Such work could not be organized by small principalities. Due to economic necessity, centralized states were created, unified for the entire irrigated valley, with the gods of individual tribes united into pantheons; priests created calendars, which was necessary to coordinate agricultural production; for this purpose they are carried out astronomical observations. Calendars were also needed by nomadic and sedentary pastoralists to regulate grazing in the valleys and driving them to mountain pastures, shearing sheep taking into account the time of lambing and much more.

Religions of the peoples of Mesopotamia in the Sumerian era until the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. e. - This is the veneration of the gods Anu, Ea and Enlil.

Scientists associate the origin of Anu with the personification of Heaven (an sky). Enlil (lil wind) - with the wind that brings rain from the mountains, and Ea - with the water element. In this pantheon of Sumerian gods, one can trace the personification of the forces of nature and the main deity - Sky. In the Semitic era (from the middle of the 3rd millennium BC), the ancient Sumerian gods were preserved, but new ones also appeared.

The rise of Babylon as a cultural, economic, commercial and political center country leads to the declaration of Marduk as the main deity. For the first time the idea of monotheism arises. Babylonian priests are trying to create a doctrine that there is only one god, Marduk, and all others are just his different manifestations. This was reflected in the policy of centralization of power in the country.

Subsequently, the idea of deifying the kings of Babylon, ruling the nations on behalf of the heavenly sun god Shamash, was put forward, who presented King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) with a scroll of laws. The Babylonians built temples dedicated to the Sun, and ziggurats were erected - artificial mountains intended for prayer on their top.

The inhabitants of the Nile Valley worshiped local noma patron deities (sacred animals). This cult was influenced by the domestication of useful animals in the prehistoric past - the cow (goddess Hathor), who gave people milk, the arable ox, who made the work of the farmer easier, the cat (goddess Bastet), who exterminated rodents, the crocodile (goddess Sobek), who cleared the Nile from pollution with waste and carrion. , lionesses (goddess Sokhmet), queens of animals, etc.

During the first unification of Egypt at the end of the 4th millennium BC. e. under the rule of people from the Edfu region, the tribal deity of this region turned into the pan-Egyptian sun god. During the rise of Memphis (around 3700 BC), the Memphis god Ptah becomes the main god of Egypt. In connection with the movement of the center of Egypt to the city of Heliopolis, the local god Atum (Ra) turns into the supreme deity of the country (about 2700 BC). Political changes in the country lead (around 2100 BC) to the creation of the center of the state in Thebes. The cult of the local deity of Thebes, Amun, is moving closer to the cult of the former god Ra. As a result, the god Amun-Ra becomes the supreme deity of the new unification of Egypt.

Scientists trace the creation of several pantheons of Egyptian gods: the Theban triad - Khonsu, Mut, Amun; the Memphis one - Ptah, Sokhmet, Nefertum and the Enneads (nine gods), among which the Heliopolis one was especially popular, consisting of four pairs of gods led by Ra, these are Shu and Tefnut, Ge and Nut, Set and Nephthys, Osiris and Isis.

Architecture Egyptian temples- This is the embodiment of the idea of the eternity of the universe. Multi-stage Mesopotamian ziggurats expressed the idea of communication with the Cosmos by a person who, rising above the surrounding space, became closer to the sky.

The architecture of Indian stupas symbolized the essence of the universe based on its four sides of a sphere-covered dome.

The proportions and architectural proportions of antiquity reflected the achievements of priestly mathematics, often dressed in a mystical garb, but which grew out of the practice of economic management of the state, the calculation of time, and the art of land surveying. Mathematical knowledge became the basis for harmonization in architecture and order in construction production.

The architects of Mesopotamia and Egypt were skilled geometers and used both arithmetic relations and geometric constructions to establish the proportionality of a structure. This is confirmed by a number of immutable facts.

For example, Herodotus (5th century BC), based on the stories of Egyptian priests, reports that “the area of the edge of the Cheops pyramid is equal to a square built at the height of the pyramid.” This historian’s message was confirmed by an analysis of full-scale measurements of the Cheops pyramid.

The relief images of mason-builders preserved on the walls of temples from the Old Kingdom era, as well as studies of the proportionality of the monuments of ancient Egypt, leave no doubt that to construct the architectural form, the priest-architects widely used simple ratios of small quantities, “sacred” integer triangles with sides 3: 4:5; 5:12:13; 20: 21: 29, as well as irrational quantities: the diagonal of a square, the diagonal of two squares, its half, etc.

The Sumerians are an ancient people who once inhabited the territory of the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the south of the modern state of Iraq (Southern Mesopotamia or Southern Mesopotamia). In the south, the border of their habitat reached the shores of the Persian Gulf, in the north – to the latitude of modern Baghdad.

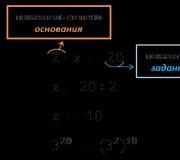

For a whole millennium, the Sumerians were the main actors in the ancient Near East. According to the currently accepted relative chronology, their history continued through the Protoliterate Period, the Early Dynastic Period, the Akkadian Period, the Gutian Period, and the Age of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Proto-literate period (XXX-XXVIII centuries)* – the time of the arrival of the Sumerians to the territory of the Southern Mesopotamia, the construction of the first temples and cities and the invention of writing. The Early Dynastic period (abbreviated as RD) is divided into three subperiods: RD I (c. 2750-c. 2615), when the statehood of the Sumerian cities was just being formed; RD II (ca. 2615-ca. 2500), when the formation of basic institutions begins Sumerian culture(temple and school); RD III (c. 2500-c. 2315) - the beginning of the internecine wars of the Sumerian rulers for supremacy in the region. Then the reign of kings of Semitic origin, immigrants from the city of Akkad (XXIV-early XXII centuries), lasted for more than a century. Sensing the weakness of the last Akkadian rulers, the Sumerian land is attacked by the wild tribes of the Gutians, who also rule the country for a century. Last century Sumerian history- the era of the III dynasty of Ur, the period of centralized government of the country, the dominance of the accounting and bureaucratic system and, paradoxically, the heyday of the school and verbal and musical arts (XXI-XX centuries). After the fall of Ur to the Elamites in 1997, the history of the Sumerian civilization ends, although the main institutions of the state and traditions created by the Sumerians during ten centuries of active work continued to be used in Mesopotamia for about two more centuries, until Hamurappi came to power (1792-1750).

Sumerian astronomy and mathematics were the most accurate in the entire Middle East. We still divide the year into four seasons, twelve months and twelve signs of the zodiac, and measure angles, minutes and seconds in sixties - just as the Sumerians first began to do. We call the constellations by their Sumerian names, translated into Greek or Arabic and through these languages came into ours. We also know astrology, which, together with astronomy, first appeared in Sumer and over the centuries has not lost its influence on the human mind.

We care about the education and harmonious upbringing of children - and the first school in the world, which taught sciences and arts, arose at the beginning of the 3rd millennium - in the Sumerian city of Ur.

When going to see a doctor, we all... receive prescriptions for medications or advice from a psychotherapist, without thinking at all that both herbal medicine and psychotherapy first developed and reached a high level precisely among the Sumerians. Receiving a subpoena and counting on the justice of the judges, we also know nothing about the founders of legal proceedings - the Sumerians, whose first legislative acts contributed to the development of legal relations in all parts of the Ancient World. Finally, thinking about the vicissitudes of fate, complaining that we were deprived at birth, we repeat the same words that the philosophizing Sumerian scribes first put into clay - but we hardly even know about it.

But perhaps the most significant contribution of the Sumerians to the history of world culture is the invention of writing. Writing has become a powerful accelerator of progress in all areas of human activity: with its help, property accounting and production control were established, economic planning became possible, a stable education system appeared, the volume of cultural memory increased, as a result of which a new type of tradition emerged, based on following the canon written text. Writing and education changed people's attitudes towards one written tradition and the value system associated with it. The Sumerian type of writing - cuneiform - was used in Babylonia, Assyria, the Hittite kingdom, the Hurrian state of Mitanni, Urartu, Ancient Iran, and the Syrian cities of Ebla and Ugarit. In the middle of the 2nd millennium, cuneiform was the letter of diplomats; even the pharaohs of the New Kingdom (Amenhotep III, Akhenaten) used it in their foreign policy correspondence. The information that came from cuneiform sources was used in one form or another by the compilers of the books of the Old Testament and Greek philologists from Alexandria, scribes of Syrian monasteries and Arab-Muslim universities. They were known both in Iran and in medieval India. In Europe of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, “Chaldean wisdom” (the ancient Greeks called Chaldeans astrologers and doctors from Mesopotamia) was held in high esteem, first by hermetic mystics, and then by oriental theologians. But over the centuries, errors in the transmission of ancient traditions inexorably accumulated, and the Sumerian language and cuneiform were so thoroughly forgotten that the sources of human knowledge had to be discovered a second time...

Note: To be fair, it must be said that at the same time as the Sumerians, writing appeared among the Elamites and Egyptians. But the influence of Elamite cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics on the development of writing and education in the Ancient World cannot be compared with the importance of cuneiform.

The author gets carried away in his admiration for Sumerian writing, firstly, omitting the facts of the presence of writing much earlier in both Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, and in Europe. And secondly, if we discard Amenhotep III and Akhenaten (who were “troublemakers” and after whom Egypt returned to old traditions), then we are talking about only one, fairly limited region...

in general, the author absolutely leaves aside all the more or less important discoveries in the field of linguistics already in the last fifty years before the publication of his book (at least the Terterian finds, indicating the presence of writing long before the Sumerians, already about 50 years ago) ...

...the father of Assyriology, Rawlinson, in 1853 [AD], when defining the language of the inventors of writing, called it “Scythian or Turkic”... Some time later, Rawlinson was already inclined to compare the Sumerian language with Mongolian, but by the end of his life he was convinced of the Turkic hypothesis... Despite the unconvincing nature of the Sumerian-Turkic kinship for linguists, this idea is still popular in Turkic-speaking countries, among those searching for noble ancient relatives.

After the Turkic languages, the Sumerian language was compared with the Finno-Ugric (also agglutinative), Mongolian, Indo-European, Malayo-Polynesian, Caucasian, Sudanese, and Sino-Tibetan languages. The latest hypothesis to date was put forward by I.M. Dyakonov in 1997 [AD]. According to the St. Petersburg scientist, the Sumerian language may be related to the languages of the Munda peoples living in the northeast of the Hindustan Peninsula and being the oldest pre-Aryan substratum of the Indian population. Dyakonov discovered common indicators of the 1st and 2nd person singular pronouns, a common indicator of the genitive case, as well as some similar kinship terms for Sumerian and Munda. His assumption can be partly confirmed by reports from Sumerian sources about contacts with the land of Aratta - a similar settlement is mentioned in ancient Indian texts of the Vedic period.

The Sumerians themselves say nothing about their origins. The most ancient cosmogonic fragments begin the history of the universe with individual cities, and this is always the city where the text was created (Lagash), or the sacred cult centers of the Sumerians (Nippur, Eredu). The texts of the beginning of the 2nd millennium name the island of Dilmun (modern Bahrain) as the place of origin of life, but they were compiled precisely during the era of active trade and political contacts with Dilmun, therefore they should not be taken as historical evidence. Much more serious is the information contained in the most ancient epic“Enmerkar and the Lord of Ararta.” It talks about a dispute between two rulers over the settlement of the goddess Inanna in their city. Both rulers revere Inanna equally, but one lives in the south of Mesopotamia, in the Sumerian city of Uruk, and the other in the east, in the country of Aratta, famous for its skilled craftsmen. Moreover, both rulers bear Sumerian names - Enmerkar and Ensukhkeshdanna. Don't these facts speak about the eastern, Iranian-Indian (of course, pre-Aryan) origin of the Sumerians?

Another evidence of the epic: the Nippur god Ninurta, fighting on the Iranian plateau with certain monsters seeking to usurp the Sumerian throne, calls them “children of An,” and meanwhile it is well known that An is the most venerable and oldest god of the Sumerians and, therefore, Ninurta is related to his opponents. Thus, the epic texts make it possible to determine, if not the region of origin of the Sumerians itself, then at least the eastern, Iranian-Indian direction of migration of the Sumerians to the Southern Mesopotamia.

this allows us to record only the fact that the war of the gods was between relatives. That's all. What does some “ancestral homeland” of the Sumerians have to do with it?..

Already by the middle of the 3rd millennium, when the first cosmogonic texts were created, the Sumerians completely forgot about their origin and even their difference from the rest of the inhabitants of Mesopotamia. They themselves called themselves sang-ngig - “black-headed”, but the Mesopotamian Semites also called themselves in their own language. If a Sumerian wanted to emphasize his origin, he called himself “the son of such and such a city,” that is, a free citizen of the city. If he wanted to contrast his country with foreign countries, then he called it with the word kalam (the etymology is unknown, written with the sign “people”), and the foreign country with the word kur (“mountain, the afterlife”). Thus, there was no national identity in a person’s self-determination at that time; What was important was territorial affiliation, which often combined a person’s origin with his social status.

Danish Sumerologist A. Westenholtz suggests understanding “Sumer” as a distortion of the phrase ki-eme-gir - “land of the noble language” (that’s what the Sumerians themselves called their language).

“noble” in the ancient concept is, first of all, “originating from the gods” or “having divine origin”...

Lower Mesopotamia has a lot of clay and almost no stone. People learned to use clay not only to make ceramics, but also for writing and sculpture. In Mesopotamian culture, sculpting prevails over carving on solid materials...

Lower Mesopotamia is not rich in vegetation. There is practically no good construction timber here (for it you need to go east, to the Zagros Mountains), but there is a lot of reed, tamarisk and date palms. Reeds grow along the shores of swampy lakes. Bundles of reeds were often used in dwellings as a seat; both the dwellings themselves and pens for livestock were built from reeds. Tamarisk tolerates heat and drought well, so it grows in large quantities in these places. Tamarisk was used to make handles for various tools, most often for hoes. The date palm was a real source of abundance for palm plantation owners. Several dozen dishes were prepared from its fruits, including flat cakes, porridge, and delicious beer. Various household utensils were made from palm tree trunks and leaves. Reeds, tamarisk, and the date palm were sacred trees in Mesopotamia, they were sung in spells, hymns to the gods and literary dialogues.

There are almost no mineral resources in Lower Mesopotamia. Silver had to be delivered from Asia Minor, gold and carnelian - from the Hindustan Peninsula, lapis lazuli - from the regions of what is now Afghanistan. Paradoxically, this sad fact played a very positive role in the history of culture: the inhabitants of Mesopotamia were constantly in contact with neighboring peoples, without experiencing a period of cultural isolation and preventing the development of xenophobia. The culture of Mesopotamia in all centuries of its existence was receptive to the achievements of others, and this gave it a constant incentive to improve.

the listed “useful” resources for primitive man have no practical value (from the standpoint of survival and nutrition). So what special incentive could there be here?..

Another feature of the local landscape is the abundance of deadly fauna. In Mesopotamia there are about 50 species of poisonous snakes, many scorpions and mosquitoes. It is not surprising that one of characteristic features This culture is the development of herbal and charm medicine. A large number of spells against snakes and scorpions have come down to us, sometimes accompanied by recipes for magical actions or herbal medicine. And in the temple decor, the snake is the most powerful amulet, which all demons and evil spirits had to fear.

The founders of Mesopotamian culture belonged to different ethnic groups and spoke unrelated languages, but had a single economic way of life. They were mainly engaged in settled cattle breeding and irrigated agriculture, as well as fishing and hunting. Cattle breeding played a role in Mesopotamian culture outstanding role, influencing the images of state ideology. The sheep and cow are most revered here. Sheep's wool was used to make excellent warm clothes, which was considered a symbol of wealth. The poor were called “having no wool” (nu-siki). They tried to find out the fate of the state from the liver of the sacrificial lamb. Moreover, the constant epithet of the king was the epithet “righteous shepherd of sheep” (sipa-zid). It arose from observations of a flock of sheep, which can only be organized with skillful direction on the part of the shepherd. The cow, which provided milk and dairy products, was no less valued. They plowed with oxen in Mesopotamia, and the productive power of the bull was admired. It is no coincidence that the deities of these places wore a horned tiara on their heads - a symbol of power, fertility and constancy of life.

We should not forget that the turn of the 3rd-2nd millennium marks the change from the era of Taurus to the era of Aries!..

Agriculture in Lower Mesopotamia could only exist thanks to artificial irrigation. Water and silt were diverted into specially built canals to be supplied to the fields if necessary. Work on the construction of canals required a large number of people and their emotional unity. Therefore, people here have learned to live in an organized way and, if necessary, to sacrifice themselves without complaint. Each city arose and developed near its canal, which created the preconditions for independent political development. Until the end of the 3rd millennium, it was not possible to form a national ideology, since each city was a separate state with its own cosmogony, calendar and characteristics of the pantheon. The unification occurred only during severe disasters or to solve important political problems, when it was necessary to elect a military leader and representatives of various cities gathered in the cult center of Mesopotamia - the city of Nippur.

The anthropological type of the Sumerians can be judged to a certain extent from the bone remains: they belonged to the Mediterranean small race of the Caucasoid large race. The Sumerian type is still found in Iraq: these are dark-skinned people of short stature, with a straight nose, curly hair and abundant facial and body hair. Hair and vegetation were carefully shaved to protect themselves from lice, which is why there are so many images of shaven-headed and beardless people in Sumerian figurines and reliefs. It was also necessary to shave for religious purposes - in particular, priests always went shaven. The same images show big eyes and big ears, but this is just a stylization, also explained by the requirements of the cult (big eyes and ears as receptacles of wisdom).

there might be something in this...

Neither men nor women of Sumer wore underwear. But until the end of their days they did not take off what they wore from their waists. naked body a magical double cord that protected life and health. The man's main clothing was a sleeveless shirt (tunic) made of sheep wool, long above the knees, and a loincloth in the form of a woolen cloth with fringe on one side. The fringed edge could be attached to legal documents instead of a seal if the person was not noble enough and did not have a personal seal. In very hot weather, a man could appear in public wearing only a bandage, and often completely naked.

Women's clothing differed relatively little from men's, but women never walked without a tunic and did not appear in one tunic without other clothing. A woman's tunic could reach to the knees or below, and sometimes had slits on the sides. A skirt was also known, sewn from several horizontal panels, with the top one wrapped in a plait-belt. Traditional clothes noble people (both men and women), in addition to the tunic and bandage, had a “wrapping” of cloth covered with sewn flags. These flags are probably nothing more than fringes made of colored yarn or fabric. There was no veil that would cover a woman’s face in Sumer. Among the headdresses they knew felt round caps, hats and caps. Shoes included sandals and boots, but people always came to the temple barefoot. When the cold days of late autumn arrived, the Sumerians wrapped themselves in a cloak-cape - a rectangular cloth, in the upper part of which one or two straps were attached on both sides, tied in a knot on the chest. But there were few cold days.

The Sumerians loved Jewelry. Rich and noble women wore a tight “collar” of adjacent strands of beads, from the chin to the neckline of the tunic. Expensive beads were made from carnelian and lapis lazuli, cheaper ones were made from colored glass (Hurrian), and the cheapest ones were made from ceramics, shell and bone. Both men and women wore a cord around their neck with a large silver or bronze pectoral ring and metal hoops on their arms and legs.

Soap had not yet been invented, so soapy plants, ash and sand were used for bathing and washing. Clean fresh water without silt was at a high price - it was carried from wells dug in several places in the city (often on high hills). Therefore, it was treasured and used most often for washing hands after a sacrificial meal. The Sumerians knew both anointings and incense. Resins of coniferous plants for making incense were imported from Syria. Women lined their eyes with black-green antimony powder, which protected them from bright sunlight. Anointings also had a pragmatic function - they prevented excessive dryness of the skin.

No matter how pure the fresh water of the city wells was, it was impossible to drink, and treatment facilities had not yet been invented. Moreover, it was impossible to drink the water of rivers and canals. What remained was barley beer - the drink of the common people, date beer - for the richer people, and grape wine - for the most noble. The food of the Sumerians, for our modern tastes, was rather meager. These are mainly flatbreads made from barley, wheat and spelt, dates, dairy products (milk, butter, cream, sour cream, cheese) and various types of fish. They ate meat only on major holidays, eating what was left of the sacrifice. Sweets were made from flour and date molasses.

The typical house of the average city dweller was one-story, built of raw brick. The rooms in it were located around an open courtyard - the place where sacrifices were made to the ancestors, and even earlier, the place of their burial. A wealthy Sumerian house was one floor above. Archaeologists count up to 12 rooms in it. Downstairs there was a living room, kitchen, toilet, people's room and a separate room in which the home altar was located. The upper floor housed the personal quarters of the owners of the house, including the bedroom. There were no windows. In rich houses there are chairs with high backs, reed mats and woolen rugs on the floor, and in bedrooms there are large beds with carved wooden headboards. The poor were content with bundles of reeds as a seat and slept on mats. Property was stored in clay, stone, copper or bronze vessels, which even included tablets from the household archives. Apparently there were no wardrobes, but dressing tables in the master's chambers and large tables where meals were taken are known. This is an important detail: in a Sumerian house, hosts and guests did not sit on the floor during meals.

From the earliest pictographic texts that came from the temple in the city of Uruk and deciphered by A.A. Vayman, we learn about the contents of the ancient Sumerian economy. The writing signs themselves, which at that time were no different from drawings, help us. There are large numbers of images of barley, spelt, wheat, sheep and sheep's wool, date palms, cows, donkeys, goats, pigs, dogs, various kinds of fish, gazelles, deer, aurochs and lions. It is clear that plants were cultivated, and some animals were bred and others were hunted. Among household items, images of vessels for milk, beer, incense and for bulk solids are especially common. There were also special vessels for sacrificial libations. The pictorial writing has preserved for us images of metal tools and a forge, spinning wheels, shovels and hoes with wooden handles, a plow, a sleigh for dragging loads across wetlands, four-wheeled carts, ropes, rolls of fabric, reed boats with highly curved noses, reed pens and stables for cattle, reed emblems of ancestral gods and much more. There is this early time and the designation of a ruler, and signs for priestly positions, and a special sign for designating a slave. All this valuable evidence of writing points, firstly, to the agricultural and pastoral nature of civilization with residual phenomena of hunting; secondly, the existence of a large temple economy in Uruk; thirdly, the presence of social hierarchy and slave-owning relations in society. Data archaeological excavations indicate the existence in the south of Mesopotamia of two types of irrigation systems: basins for storing spring flood waters and long-distance main canals with permanent dam units.

in general, everything points to a fully formed society in the form that continues to be observed...

Since all the economic archives of early Sumer came to us from the temples, the idea arose and strengthened in science that the Sumerian city itself was a temple city and that all the land in Sumer belonged exclusively to the priesthood and temples. At the dawn of Sumerology, this idea was expressed by the German-Italian researcher A. Deimel, and in the second half of the twentieth century [AD] he was supported by A. Falkenstein. However, from the works of I.M. Dyakonov, it became clear that, in addition to the temple land, there was also community land in Sumerian cities, and there was much more of this community land. Dyakonov calculated the city population and compared it with the number of temple personnel. Then he compared the total area of the temple lands in the same way with the total area of the entire land of Southern Mesopotamia. The comparisons were not in favor of the temple. It turned out that the Sumerian economy knew two main sectors: the community economy (uru) and the temple economy (e). In addition to numerical relationships, documents on the purchase and sale of land, which were completely ignored by Daimel’s supporters, also speak of non-temple communal land.

The picture of Sumerian land ownership is best drawn from the accounting documents that came from the city of Lagash. According to temple economic documents, there were three categories of temple land:

1. Priestly land (ashag-nin-ena), which was cultivated by temple agricultural workers, using livestock and tools issued to them by the temple. For this they received land plots and payments in kind.

2. Feeding land (ashag-kur), which was distributed in the form of separate plots to officials of the temple administration and various artisans, as well as elders of groups of agricultural workers. The same category began to include fields issued personally to the ruler of the city as an official.

3. Cultivation land (ashag-nam-uru-lal), which was also issued from the temple land fund in separate plots, but not for service or work, but for a share in the harvest. It was taken by temple employees and workers in addition to their official allotment or ration, as well as by the ruler’s relatives, members of the staff of other temples, and, perhaps, in general by any free citizen of the city who had the strength and time to process an additional allotment.

Representatives of the community nobility (including priests) either did not have plots on the temple land at all, or had only small plots, mainly on cultivation land. From the documents of purchase and sale we know that these persons, like the relatives of the ruler, had large land holdings, received directly from the community, and not from the temple.

The existence of extra-temple land is reported by the most Various types documents classified by science as purchase and sale agreements. These are clay tablets with a lapidary statement of the main aspects of the transaction, and inscriptions on obelisks of rulers, which report the sale of large plots of land to the king and describe the transaction procedure itself. All this evidence is undoubtedly important to us. From them it turns out that the non-temple land was owned by a large family community. This term means a collective united by a common origin on the paternal line, a community economic life and land ownership and including more than one family unit. Such a team was headed by a patriarch, who organized the procedure for transferring the land to the buyer. This procedure consisted of the following parts:

1. ritual of making a transaction - driving a peg into the wall of the house and pouring oil next to it, handing over the rod to the buyer as a symbol of the territory being sold;

2. payment by the buyer of the price of the land plot in barley and silver;

3. additional payment for the purchase;

4. “gifts” to the seller’s relatives and low-income community members.

The Sumerians cultivated barley, spelled and wheat. Payments for purchase and sale were carried out in measures of barley grain or in silver (in the form of silver scrap by weight).

Cattle breeding in Sumer was transhumance: cattle were kept in pens and stables and were driven out to pasture every day. From the texts, shepherds-goatherds, shepherds of cow herds are known, but the most famous are the shepherds of sheep.

Crafts and trade developed very early in Sumer. The oldest lists of names of temple artisans retained terms for the professions of blacksmith, coppersmith, carpenter, jeweler, saddler, tanner, potter, and weaver. All artisans were temple workers and received both in-kind payments and additional plots of land for their work. However, they rarely worked on the land and over time they lost any connection with community and agriculture. real connection. Known from the most ancient lists are both trading agents and shipmen who transported goods across the Persian Gulf for trade in eastern countries, but they also worked for the temple. A special, privileged part of the artisans included scribes who worked in a school, in a temple or in a palace and received large payments in kind for their work.

Is there a situation here similar to the initial version only about the temple ownership of the land?.. It is hardly possible that artisans were only at the temples...

In general, the Sumerian economy can be considered as an agricultural-pastoral economy with a subordinate position of crafts and trade. It was based on a subsistence economy that fed only the residents of the city and its authorities and only occasionally supplied its products to neighboring cities and countries. The exchange was predominantly in the direction of imports: the Sumerians sold surplus agricultural products, importing building timber and stone into their country, precious metals and incense.

The overall structure of the Sumerian economy outlined in diachronic terms did not undergo significant changes. With the development of the despotic power of the kings of Akkad, strengthened by the monarchs of the III dynasty of Ur, all more land ended up in the hands of insatiable rulers, but they never owned all the cultivable land of Sumer. And although the community had already lost its political power by this time, the Akkadian or Sumerian king still had to buy the land from it, scrupulously observing the procedure described above. Over time, craftsmen were more and more secured by the king and the temples, which reduced them almost to the status of slaves. The same thing happened with trading agents, who were accountable to the king in all their actions. Against their background, the work of a scribe was invariably viewed as free and well-paid work.

...already in the earliest pictographic texts from Uruk and Jemdet Nasr there are signs to designate managerial, priestly, military and craft positions. Therefore, no one was separated from anyone, and people of different social purposes lived in the very first years of the existence of the ancient civilization.

...the population of the Sumerian city-state was divided as follows:

1. Nobles: the ruler of the city, the head of the temple administration, priests, members of the council of elders of the community. These people had tens and hundreds of hectares of communal land in the form of family-community or clan, and often individual ownership, exploiting clients and slaves. The ruler, in addition, often used the temple land for personal enrichment.

2. Ordinary community members who owned plots of communal land as family-communal ownership. They made up more than half of the total population.

3. Temple clients: a) members of the temple administration and artisans; b) people subordinate to them. These are former community members who have lost community ties.

4. Slaves: a) temple slaves, who differed little from the lower categories of clients; b) slaves of private individuals (the number of these slaves was relatively small).

Thus we see that social structure Sumerian society is quite clearly divided into two main economic sectors: community and temple. Nobility is determined by the amount of land, the population either cultivates its own plot or works for the temple and large landowners, artisans are attached to the temple, and priests are assigned to communal land.

The ruler of the Sumerian city in the initial period of the history of Sumer was en (“lord, owner”), or ensi. He combined the functions of a priest, military leader, mayor and chairman of parliament. His responsibilities included the following:

1. Leadership of community worship, especially participation in the rite of sacred marriage.

2. Management of construction work, especially temple construction and irrigation.

3. Leadership of an army of persons dependent on the temples and on him personally.

4. Presidency of the people's assembly, especially the council of community elders.

En and his people, according to tradition, had to ask permission for their actions from the people's assembly, which consisted of the “youths of the city” and the “elders of the city.” We learn about the existence of such a collection mainly from hymn-poetic texts. As some of them show, even without receiving the approval of the assembly or having received it from one of the chambers, the ruler could still decide on his risky undertaking. Subsequently, as power was concentrated in the hands of one political group, the role of the people's assembly completely disappeared.

In addition to the position of city ruler, the title lugal - “big man”, in different cases translated either as “king” or “master”, is also known from Sumerian texts. I.M. Dyakonov in his book “Paths of History” suggests translating it with the Russian word “prince”. This title first appears in the inscriptions of the rulers of the city of Kish, where it quite possibly originated. Originally it was the title of a military leader, who was chosen from among the En supreme gods Sumer in sacred Nippur (or in his city with the participation of the Nippur gods) and temporarily occupied the position of master of the country with the powers of a dictator. But later they became kings not by choice, but by inheritance, although during enthronement they still observed the old Nippur rite. Thus, one and the same person was simultaneously both the En of a city and the Lugal of the country, so the struggle for the title of Lugal went on at all times in the history of Sumer. True, quite soon the difference between the Lugal and En titles became obvious. During the capture of Sumer by the Guts, not a single Ensi had the right to bear the title of Lugal, since the invaders called themselves Lugals. And by the time of the III dynasty of Ur, ensi were officials of city administrations, completely subordinate to the ox of the lugal.

Documents from the archives of the city of Shuruppak (XXVI century) show that in this city people ruled in turns, and the ruler changed annually. Each line, apparently, fell by lot not only on this or that person, but also on a certain territorial area or temple. This indicates the existence of a kind of collegial governing body, whose members took turns holding the position of elder-eponym. In addition, there is evidence from mythological texts about the order in the reign of the gods. Finally, the term for the term of government, lugal bala, literally means “queue.” Does this mean that the earliest form of government in the Sumerian city-states was precisely the alternate rule of representatives of neighboring temples and territories? It is quite possible, but it is quite difficult to prove.

If the ruler occupied the top step on the social ladder, then slaves huddled at the foot of this ladder. Translated from Sumerian, “slave” means “lowered, lowered.” First of all, the modern slang verb “to lower” comes to mind, that is, “to deprive someone of social status, subordinating him as property.” But we also have to take into account the historical fact that the first slaves in history were prisoners of war, and the Sumerian army fought their opponents in the Zagros mountains, so the word for slave may simply mean “brought down from the eastern mountains.” Initially, only women and children were taken prisoner, since the weapons were imperfect and it was difficult to escort captured men. After capture they were most often killed. But later, with the advent of bronze weapons, men were also saved. The labor of slave prisoners of war was used in private farms and in churches...

In addition to captive slaves, in the last centuries of Sumer there also appeared debtor slaves, captured by their creditors until the debt was paid with interest. The fate of such slaves was much easier: in order to regain their former status, they only needed to be ransomed. Captive slaves, even having mastered the language and started a family, could rarely count on freedom.

At the turn of the 4th and 3rd millennia, on the territory of the Southern Mesopotamia, three people completely different in origin and language began to live in a common household. The first to come here were native speakers of a language conventionally called “banana” due to the large number of words with repeating syllables (such as Zababa, Huwawa, Bunene). It was to their language that the Sumerians owed the terminology in the field of crafts and metalworking, as well as the names of some cities. The speakers of the “banana” language did not leave any memory of the names of their tribes, since they were not lucky enough to invent writing. But their material traces are known to archaeologists: in particular, they were the founders of an agricultural settlement that now bears the Arabic name El-Ubeid. Masterpieces of ceramics and sculpture found here testify to the high development of this nameless culture.

Since in the early stages the writing was pictographic and was not focused at all on the sound of the word (but only on its meaning), it is simply impossible to detect the “banana” structure of the language with such writing!..

The second to come to Mesopotamia were the Sumerians, who founded the settlements of Uruk and Jemdet-Nasr (also an Arabic name) in the south. The last to come from Northern Syria in the first quarter of the 3rd millennium were the Semites, who settled mostly in the north and north-west of the country. Sources that come from different eras of Sumerian history show that all three peoples lived compactly in a common territory, with the difference that the Sumerians lived mainly in the south, the Semites - in the northwest, and the “banana” people - both in the south and In the north of the country. There was nothing resembling national differences, and the reason for such peaceful coexistence was that all three peoples were newcomers to this territory, equally experienced the difficulties of life in Mesopotamia and considered it an object of joint development.

The author's arguments are very weak. As not-so-distant historical practice shows (the development of Siberia, the Zaporozhye Cossacks), millennia are not needed at all for adaptation to a new territory. After just a hundred or two years, people consider themselves completely “at home” on this land, where their ancestors came not so long ago. Most likely, any “relocations” have nothing to do with it at all. They might not have existed at all. And the “banana” style of language is observed quite often among primitive peoples throughout the Earth. So their “trace” is only the remnants of a more ancient language of the same population... It would be interesting to look from this angle at the vocabulary of the “banana” language and later terms.

The organization of a network of main canals, which existed without fundamental changes until the middle of the 2nd millennium, was decisive for the history of the country.

By the way, a very interesting fact. It turns out that a certain people came to this area; for no apparent reason he built a developed network of canals and dams; and for one and a half thousand years (!) this system did not change at all!!! Why then do historians struggle with searching for the “ancestral homeland” of the Sumerians? They just need to find traces of a similar irrigation system, and that’s all! a new place already with these skills!.. somewhere in the old place he should have “trained” and “developed his skills”!.. But this is nowhere to be found!!! This is another problem with the official version of history...

The main centers of state formation - cities - were also connected to the network of canals. They grew up on the site of the original groups of agricultural settlements, which were concentrated on individual drained and irrigated areas, reclaimed from swamps and deserts in previous millennia. Cities were formed by moving residents of abandoned villages to the center. However, the matter most often did not reach the point of completely relocating the entire district to one city, since the residents of such a city would not be able to cultivate the fields within a radius of more than 15 kilometers and the already developed land lying beyond these limits would have to be abandoned. Therefore, in one district, three or four or more interconnected cities usually arose, but one of them was always the main one: the center of common cults and the administration of the entire district were located here. I.M. Dyakonov, following the example of Egyptologists, proposed calling each such district a nom. In Sumerian it was called ki, which means “earth, place.” The city itself, which was the center of the district, was called uru, which is usually translated as “city”. However, in the Akkadian language this word corresponds to alu - “community”, so we can assume the same original meaning for the Sumerian term. Tradition has assigned the status of the first fenced settlement (i.e., the city itself) to Uruk, which is quite likely, since archaeologists have found fragments of a high wall surrounding this settlement.

Header photo: @thehumanist.com

If you find an error, please highlight a piece of text and click Ctrl+Enter.

1. RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW AND ART OF THE POPULATION OF LOWER MESOPOTAMIA

The human consciousness of the early Chalcolithic (Copper-Stone Age) had already advanced far in the emotional and mental perception of the world. At the same time, however, the main method of generalization remained an emotionally charged comparison of phenomena on the principle of metaphor, that is, by combining and conditionally identifying two or more phenomena with some common typical feature (the sun is a bird, since both it and the bird soar above us ; earth is mother). This is how myths arose, which were not only a metaphorical interpretation of phenomena, but also an emotional experience. In circumstances where verification by socially recognized experience was impossible or insufficient (for example, outside the technical methods of production), “sympathetic magic” was obviously at work, by which here is meant the indiscriminateness (in judgment or in practical action) of the degree of importance of logical connections.

At the same time, people began to realize the existence of certain patterns that affected their life and work and determined the “behavior” of nature, animals and objects. But they could not yet find any other explanation for these patterns, except that they are supported by the intelligent actions of some powerful beings, in which the existence of the world order was metaphorically generalized. These powerful living principles themselves were presented not as an ideal “something”, not as a spirit, but as materially active, and therefore materially existing; therefore, it was assumed that it was possible to influence their will, for example, to appease them. It is important to note that logically justified actions and magically justified actions were then perceived as equally reasonable and useful for human life, including production. The difference was that the logical action had a practical, empirically visual explanation, and the magical (ritual, cult) action had a mythical explanation; it represented in the eyes of an ancient man a repetition of a certain action performed by a deity or an ancestor at the beginning of the world and performed in the same circumstances to this day, because historical changes in those times of slow development were not really felt and the stability of the world was determined by the rule: do as they did gods or ancestors at the beginning of time. The criterion of practical logic was not applicable to such actions and concepts.

Magical activity - attempts to influence the personified patterns of nature with emotional, rhythmic, “divine” words, sacrifices, ritual movements - seemed as necessary for the life of the community as any socially useful work.

In the Neolithic era (New Stone Age), apparently, there was already a feeling of the presence of certain abstract connections and patterns in the surrounding reality. Perhaps this was reflected, for example, in the predominance of geometric abstractions in the pictorial representation of the world - humans, animals, plants, movements. The place of a chaotic heap of magical drawings of animals and people (even if very accurately and observantly reproduced) was taken by an abstract ornament. At the same time, the image did not lose its magical purpose and at the same time was not isolated from everyday human activity: artistic creativity accompanied the home production of things needed in every household, be it dishes or colored beads, figurines of deities or ancestors, but especially, of course, the production of objects intended, for example, for cult-magical holidays or for burial (so that the deceased could use them in the afterlife) .

The creation of objects for both domestic and religious purposes was a creative process in which the ancient master was guided by artistic flair (whether he was aware of it or not), which in turn developed during his work.

Neolithic and early Chalcolithic ceramics show us one of the important stages of artistic generalization, the main indicator of which is rhythm. The sense of rhythm is probably organically inherent in man, but, apparently, man did not immediately discover it in himself and was far from immediately able to embody it figuratively. In Paleolithic images we feel little rhythm. It appears only in the Neolithic as a desire to streamline and organize space. From the painted dishes of different eras, one can observe how a person learned to generalize his impressions of nature, grouping and stylizing the objects and phenomena that were revealed to his eyes in such a way that they turned into a slender, geometrized plant, animal or abstract ornament, strictly subordinated to rhythm. Starting from the simplest dot and line patterns on early ceramics to complex symmetrical, as if moving images on vessels of the 5th millennium BC. e., all compositions are organically rhythmic. It seems that the rhythm of colors, lines and forms embodied a motor rhythm - the rhythm of the hand slowly rotating the vessel during sculpting (up to the potter's wheel), and perhaps the rhythm of the accompanying chant. The art of ceramics also created the opportunity to capture thought in conventional images, for even the most abstract pattern carried information supported by oral tradition.

We encounter an even more complex form of generalization (but not only of an artistic nature) when studying Neolithic and early Eneolithic sculpture. Figurines sculpted from clay mixed with grain, found in places where grain was stored and in hearths, with emphasized female and especially maternal forms, phalluses and figurines of bulls, very often found next to human figurines, syncretically embodied the concept of earthly fertility. The Lower Mesopotamian male and female figurines of the early 4th millennium BC seem to us to be the most complex form of expression of this concept. e. with an animal-like muzzle and inserts for material samples of vegetation (grains, seeds) on the shoulders and in the eyes. These figurines cannot yet be called fertility deities - rather, they are a step preceding the creation of the image of the patron deity of the community, the existence of which we can assume a little more late time, exploring the development of architectural structures, where evolution follows the line: open-air altar - temple.

In the IV millennium BC. e. Painted ceramics are replaced by unpainted red, gray or yellowish-gray dishes covered with glassy glaze. Unlike ceramics of previous times, which were made exclusively by hand or on a slowly rotating pottery wheel, it is made on a rapidly rotating wheel and very soon completely replaces hand-made dishes.

The culture of the Proto-Literary Period can already be confidently called Sumerian, or at least Proto-Sumerian, at its core. Its monuments are spread throughout Lower Mesopotamia, covering Upper Mesopotamia and the region along the river. Tiger. The highest achievements of this period include: the flourishing of temple building, the flourishing of the art of glyptics (seal carving), new forms of plastic arts, new principles of representation and the invention of writing.

All the art of that time, like the worldview, was colored by cult. Let us note, however, that when speaking about the communal cults of ancient Mesopotamia, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the Sumerian religion as a system. True, common cosmic deities were revered everywhere: “Heaven” An (Akkadian Anu); “Lord of the Earth,” the deity of the World Ocean on which the earth floats, Enki (Akkadian Eya); "Lord of the Breath", the deity of ground forces, Enlil (Akkadian Ellil), also the god of the Sumerian tribal union centered in Nippur; numerous “mother goddesses”, gods of the Sun and Moon. But of greater importance were the local patron gods of each community, usually each with his wife and son, with many associates. There were countless small good and evil deities associated with grain and livestock, with the hearth and grain barn, with diseases and misfortunes. They were for the most part different in each of the communities, different myths were told about them, contradictory to each other.

Temples were not built to all gods, but only to the most important ones, mainly to the god or goddess - the patrons of a given community. The outer walls of the temple and the platform were decorated with projections evenly spaced from each other (this technique was repeated with each successive rebuilding). The temple itself consisted of three parts: a central one in the form of a long courtyard, in the depths of which there was an image of the deity, and symmetrical side chapels on both sides of the courtyard. At one end of the courtyard there was an altar, at the other end there was a table for sacrifices. The temples of that time in Upper Mesopotamia had approximately the same layout.

Thus, in the north and south of Mesopotamia, a certain type of religious building was formed, where some building principles were consolidated and became traditional for almost all later Mesopotamian architecture. The main ones are: 1) construction of the sanctuary in one place (all later reconstructions include the previous ones, and the building is thus never moved); 2) a high artificial platform on which the central temple stands and to which stairs lead on both sides (subsequently, perhaps precisely as a result of the custom of building a temple in one place instead of one platform, we already encounter three, five and, finally, seven platforms, one above the other with a temple at the very top - the so-called ziggurat). The desire to build high temples emphasized the antiquity and originality of the origin of the community, as well as the connection of the sanctuary with the heavenly abode of God; 3) a three-part temple with a central room, which is an open courtyard on top, around which side extensions are grouped (in the north of Lower Mesopotamia such a courtyard could be covered); 4) dividing the outer walls of the temple, as well as the platform (or platforms), with alternating projections and niches.

From ancient Uruk we know a special structure, the so-called “Red Building” with a stage and pillars decorated with mosaic patterns - presumably a courtyard for public gatherings and council.

With the beginning of urban culture (even the most primitive) it opens new stage and in the development of the visual arts of Lower Mesopotamia. The culture of the new period becomes richer and more diverse. Instead of seals, stamps appear new form seals - cylindrical.

Sumerian cylinder seal. Saint Petersburg. Hermitage

The plastic art of early Sumer is closely related to glyptics. Amulet seals in the form of animals or animal heads, which were so common in the Protoliterate Period, can be considered a form combining glyptics, relief and circular sculpture. Functionally, all these items are seals. But if this is a figurine of an animal, then one side of it will be cut flat and additional images will be cut out on it in deep relief, intended for imprinting on clay, usually associated with the main figure, for example, on the back side of the lion’s head, executed in rather high relief , small lions are carved, on the back there are figures of a ram - horned animals or a person (apparently a shepherd).

The desire to convey the depicted nature as accurately as possible, especially when it comes to representatives of the animal world, is characteristic of the art of Lower Mesopotamia of this period. Small figurines of domestic animals - bulls, rams, goats, made in soft stone, various scenes from the life of domestic and wild animals on reliefs, cult vessels, seals amaze, first of all, with an accurate reproduction of the body structure, so that not only the species, but also the breed is easily determined animal, as well as poses and movements, conveyed vividly and expressively, and often surprisingly laconically. However, there is still almost no real round sculpture.

Another characteristic feature of early Sumerian art is its narrative nature. Each frieze on the cylinder seal, each relief image is a story that can be read in order. A story about nature, about the animal world, but most importantly - a story about yourself, about a person. For only in the Protoliterate period does man, his theme, appear in art.

Stamp seals. Mesopotamia. End of IV - beginning of III millennium BC. Saint Petersburg. Hermitage

Images of man are found even in the Paleolithic, but they cannot be considered an image of man in art: man is present in Neolithic and Eneolithic art as a part of nature, he has not yet isolated himself from it in his consciousness. Early art is often characterized by a syncretic image - human-animal-vegetal (such as, say, frog-like figurines with dimples for grains and seeds on the shoulders or an image of a woman feeding a baby animal) or human-phallic (i.e. a human phallus, or just a phallus, as a symbol of reproduction).

In the Sumerian art of the Protoliterate Period, we already see how man began to separate himself from nature. The art of Lower Mesopotamia of this period appears before us, therefore, as a qualitatively new stage in man’s relationship to the world around him. It is no coincidence that the cultural monuments of the Protoliterate period leave the impression of the awakening of human energy, a person’s awareness of his new capabilities, an attempt to express himself in the world around him, which he is mastering more and more.

Monuments of the Early Dynastic period are represented by a significant number of archaeological finds, which allow us to speak more boldly about some general trends in art.

In architecture, the type of temple on a high platform was finally taking shape, which was sometimes (and even usually the entire temple site) surrounded by a high wall. By this time, the temple was taking on more laconic forms - the auxiliary rooms were clearly separated from the central religious premises, their number was decreasing. Columns and half-columns disappear, and with them the mosaic cladding. The main technique decoration Among the monuments of temple architecture, the division of the outer walls into projections remains. It is possible that during this period the multi-stage ziggurat of the main city deity was established, which would gradually displace the temple on the platform. At the same time, there were also temples of minor deities, which were smaller in size, built without a platform, but usually also within the temple site.

A unique architectural monument was discovered in Kish - a secular building, which represents the first example of a combination of a palace and a fortress in Sumerian construction.

Sculpture monuments are mostly small (25-40 cm) figures made of local alabaster and softer types of stone (limestone, sandstone, etc.). They were usually placed in cult niches of temples. The northern cities of Lower Mesopotamia are characterized by exaggeratedly elongated, and the southern, on the contrary, exaggeratedly shortened proportions of figurines. All of them are characterized by a strong distortion of the proportions of the human body and facial features, with a sharp emphasis on one or two features, especially often the nose and ears. Such figures were placed in temples so that they would represent there and pray for the one who placed them. They did not require a specific resemblance to the original, as, say, in Egypt, where the early brilliant development of portrait sculpture was due to the requirements of magic: otherwise the soul-double could confuse the owner; here a short inscription on the figurine was quite enough. Magical purposes were apparently reflected in the emphasized facial features: large ears (for the Sumerians - receptacles of wisdom), wide open eyes, in which a pleading expression is combined with the surprise of a magical epiphany, hands folded in a prayerful gesture. All this often turns awkward and angular figures into lively and expressive ones. The transfer of the internal state turns out to be much more important than the transfer of the external bodily form; the latter is developed only to the extent that it meets the internal task of sculpture - to create an image endowed with supernatural properties (“all-seeing”, “all-hearing”). Therefore, in the official art of the Early Dynastic period we no longer encounter that original, sometimes free interpretation that marked the best works of art of the Protoliterate period. The sculptural figures of the Early Dynastic period, even if they depicted fertility deities, are completely devoid of sensuality; their ideal is the desire for the superhuman and even inhuman.

In the nome-states that were constantly at war with each other, there were different pantheons, different rituals, there was no uniformity in mythology (except for the preservation of the common main function of all deities of the 3rd millennium BC: these are primarily communal gods of fertility). Accordingly, despite the unity of the general character of the sculpture, the images are very different in detail. Cylinder seals with images of heroes and rearing animals begin to dominate in glyptics.

Jewelry of the Early Dynastic period, known mainly from materials from excavations of Ur tombs, can rightfully be classified as masterpieces of jewelry creativity.

The art of Akkadian times is perhaps most characterized by the central idea of a deified king, who appears first in historical reality, and then in ideology and art. If in history and legends he appears as a man not from the royal family, who managed to achieve power, gathered a huge army and, for the first time in the entire existence of nome states in Lower Mesopotamia, subjugated all of Sumer and Akkad, then in art he courageous man with emphatically energetic features of a lean face: regular, clearly defined lips, a small nose with a hump - an idealized portrait, perhaps generalized, but quite accurately conveying the ethnic type; this portrait fully corresponds to the idea of the victorious hero Sargon of Akkad, which has developed from historical and legendary data (such, for example, is a copper portrait head from Nineveh - the alleged image of Sargon). In other cases, the deified king is depicted making a victorious campaign at the head of his army. He climbs the steep slopes ahead of the warriors, his figure is larger than the others, the symbols and signs of his divinity shine above his head - the Sun and the Moon (the stele of Naram-Suen in honor of his victory over the highlanders). He also appears as a mighty hero with curls and a curly beard. The hero fights with a lion, his muscles tense, with one hand he restrains the rearing lion, whose claws scratch the air in impotent rage, and with the other he plunges a dagger into the predator’s scruff (a favorite motif of Akkadian glyptics). To some extent, changes in the art of the Akkadian period are associated with the traditions of the northern centers of the country. There is sometimes talk of "realism" in the art of the Akkadian period. Of course, there can be no talk of realism in the sense as we now understand this term: it is not the truly visible (even typical) features that are recorded, but the features that are essential for the concept of a given subject. Nevertheless, the impression of the life-likeness of the person depicted is very acute.

Found in Susa. Victory of the king over the Lullubeys. OK. 2250 BC

Paris. LouvreThe events of the Akkadian dynasty shook the established Sumerian priestly traditions; Accordingly, the processes taking place in art for the first time reflected interest in the individual. The influence of Akkadian art lasted for centuries. It can also be found in monuments last period Sumerian history - the III dynasty of Ur and the Issin dynasty. But in general, the monuments of this later time leave an impression of monotony and stereotyping. This corresponds to reality: for example, the masters-gurushas of the huge royal craft workshops of the III dynasty of Ur worked on the seals, having cut their teeth on the clear reproduction of the same prescribed theme - the worship of the deity.

2. SUMERIAN LITERATURE

In total, we currently know about one hundred and fifty monuments of Sumerian literature (many of them have been preserved in the form of fragments). Among them are poetic records of myths, epic tales, psalms, wedding and love songs associated with the sacred marriage of a deified king with a priestess, funeral laments, laments about social disasters, hymns in honor of kings (starting from the III dynasty of Ur), literary imitations of royal inscriptions; Didactics are very widely represented - teachings, edifications, debates, dialogues, collections of fables, anecdotes, sayings and proverbs.

Of all the genres of Sumerian literature, hymns are the most fully represented. Their earliest records date back to the middle of the Early Dynastic period. Of course, the hymn is one of the most ancient ways of collectively addressing the deity. The recording of such a work had to be done with special pedantry and punctuality; not a single word could be changed arbitrarily, since not a single image of the anthem was accidental, behind each there was mythological content. Hymns are designed to be read aloud - by an individual priest or choir, and the emotions that arose during the performance of such a work are collective emotions. The enormous importance of rhythmic speech, perceived emotionally and magically, comes to the fore in such works. Usually the hymn praises the deity and lists the deeds, names and epithets of the god. Most of the hymns that have come down to us are preserved in the school canon of the city of Nippur and are most often dedicated to Enlil, the patron god of this city, and other deities of his circle. But there are also hymns to kings and temples. However, hymns could only be dedicated to deified kings, and not all kings in Sumer were deified.

Along with hymns, liturgical texts are laments, which are very common in Sumerian literature (especially laments about public disasters). But the oldest monument of this kind known to us is not liturgical. This is a “cry” for the destruction of Lagash by the king of Umma, Lugalzagesi. It lists the destruction caused in Lagash and curses the culprit. The rest of the laments that have come down to us - the lament about the death of Sumer and Akkad, the lament “Curse on the city of Akkad”, the lament about the death of Ur, the lament about the death of King Ibbi-Suen, etc. - are certainly of a ritual nature; they are addressed to the gods and are close to spells.

Among the cult texts is a remarkable series of poems (or chants), starting with Inapa's Walk into the Underworld and ending with the Death of Dumuzi, reflecting the myth of dying and resurrecting deities and associated with the corresponding rituals. The goddess of carnal love and animal fertility Innin (Inana) fell in love with the god (or hero) shepherd Dumuzi and took him as her husband. However, she then descended into the underworld, apparently to challenge the power of the queen of the underworld. Killed, but brought back to life by the cunning of the gods, Inana can return to earth (where, meanwhile, all living things have ceased to reproduce) only by giving a living ransom for herself to the underworld. Inana is revered in different cities Sumer and each has a spouse or son; all these deities bow before her and beg for mercy; only Dumuzi proudly refuses. Dumuzi is betrayed to the evil messengers of the underworld; in vain his sister Geshtinana (“Vine of Heaven”) three times turns him into an animal and hides him; Dumuzi is killed and taken to the underworld. However, Geshtinana, sacrificing herself, ensures that Dumuzi is released to the living for six months, during which time she herself goes into the world of the dead in return for him. While the shepherd god reigns on earth, the plant goddess dies. The structure of the myth turns out to be much more complex than the simplified mythological plot of the dying and resurrection of the fertility deity, as it is usually presented in popular literature.

The Nippur canon also includes nine tales about the exploits of heroes attributed by the “Royal List” to the semi-legendary First Dynasty of Uruk - Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. The Nippur canon apparently began to be created during the III dynasty of Ur, and the kings of this dynasty were closely connected with Uruk: its founder traced his family back to Gilgamesh. The inclusion of Uruk legends in the canon most likely occurred because Nippur was a cult center that was always associated with the dominant city of the time. During the III dynasty of Ur and the I dynasty of Issin, a uniform Nippurian canon was introduced in the e-dubs (schools) of other cities of the state.

All heroic tales that have come down to us are at the stage of forming cycles, which is usually characteristic of epic (grouping heroes by place of their birth is one of the stages of this cyclization). But these monuments are so heterogeneous that it is difficult to unite them general concept"epic". These are compositions from different periods, some of which are more perfect and complete (like the wonderful poem about the hero Lugalbanda and the monstrous eagle), others less so. However, it is impossible to form even an approximate idea of the time of their creation - various motifs could be included in them at different stages of their development, and the legends could be modified over the centuries. One thing is clear: before us is an early genre from which the epic will subsequently develop. Therefore, the hero of such a work is not yet an epic hero-hero, monumental and often tragic figure; he is rather a lucky fellow from a fairy tale, a relative of the gods (but not a god), a mighty king with the features of a god.

Very often in literary criticism, the heroic epic (or primordial epic) is contrasted with the so-called mythological epic (in the first, people act, in the second, gods). Such a division is hardly appropriate in relation to Sumerian literature: the image of a god-hero is much less characteristic of it than the image of a mortal hero. In addition to those mentioned, two epic or proto-epic tales are known, where the hero is a deity. One of them is a legend about the struggle of the goddess Innin (Inana) with the personification of the underworld, called “Mount Ebeh” in the text, the other is a story about the war of the god Ninurta with the evil demon Asak, also an inhabitant of the underworld. Ninurta simultaneously acts as a hero-ancestor: he builds a dam-embankment from a pile of stones to isolate Sumer from the waters of the primordial ocean, which overflowed as a result of the death of Asak, and diverts the flooded fields into the Tigris.

More common in Sumerian literature are works devoted to descriptions of the creative acts of deities, the so-called etiological (i.e., explanatory) myths; at the same time, they give an idea of the creation of the world as it was seen by the Sumerians. It is possible that there were no complete cosmogonic legends in Sumer (or they were not written down). It is difficult to say why this is so: it is hardly possible that the idea of the struggle between the titanic forces of nature (gods and titans, elders and younger gods etc.) was not reflected in the Sumerian worldview, especially since the theme of the dying and resurrection of nature (with the departure of the deity into the underworld) was developed in detail in Sumerian mythography - not only in the stories about Innin-Inan and Dumuzi, but also about other gods , for example about Enlil.

The structure of life on earth, the establishment of order and prosperity on it is perhaps the favorite topic of Sumerian literature: it is filled with stories about the creation of deities who should monitor the earthly order, take care of the distribution of divine responsibilities, the establishment of a divine hierarchy, and the settlement of the earth with living beings and even about the creation of individual agricultural implements. The main active creator gods are usually Enki and Enlil.