A quarrel will not lead to any good explanation. Quarreling does not lead to good things

From 2016, Hermitage Day will become an official city holiday. The corresponding document has already been signed by the governor of St. Petersburg. This means that the Hermitage, which has a global network and dictates fashion in the European museum sphere, is becoming closer to the city.

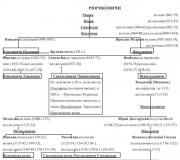

Hermitage Day, which is celebrated annually on December 7, will become an official holiday in St. Petersburg. The decision has already been approved by the governor and is now undergoing legal procedures. With this news, Hermitage Director Mikhail Piotrovsky began his annual press conference. He noted that the city holiday will give the museum the opportunity to hold various events, for example, a 3D show on Palace Square. Among the main achievements of the anniversary year: the Hermitage received the prestigious “Museum Olympus” award in two categories at once - “Museum of the Year” and “Exhibition of the Year”.

“The Hermitage has become a global museum, which has never been open to the world as it is now. In many ways, the Hermitage dictates museum fashion in the world: the creation of centers, open storage facilities, and much more.”

The Hermitage today is a dynamic combination of permanent exhibitions, new exhibition spaces, rotating exhibitions, open storage, exhibitions outside the Hermitage in any part globe, which significantly expanded the museum’s exhibition capabilities and audience. As proof of this, the day before at the restoration and storage center " Old village» five new exhibitions were opened. Halls for open storage of unique exhibits from the Department of the Ancient World. The architecture, necropolis, amphorae, sarcophagi and inscriptions are all being shown to the public for the first time.

Anna Trofimova, Head. Department of the Ancient World of the State Hermitage:

"In every museum there is that part of the collection that is on display, and that part that is in the storeroom. This is a constant choice: the best - for the exhibition, and those that are not so famous - for the storeroom. But the concept of the value of a historical, cultural monument, art is changing. And now we, even in amphoras, which a hundred years ago seemed like such a mass material, uninteresting, we see so much information in an ancient amphora, we can say up to the decade when it was made due to the mark and many other things."

The year for the Hermitage is not yet over. In the Nikolaevsky Hall Winter Palace The exhibition “Catherine the Second and Stanislav August” opened, which presented more than one hundred and fifty works of fine and applied arts"two enlightened rulers." This is one of the most mysterious and at the same time romantic episodes of Russian-Polish relations. And the goal is to compare the collections of two monarchs, one of which formed the basis for the formation of the Hermitage.

WITH ergey Androsov, exhibition curator, head. department of Western European visual arts State Hermitage:

“In the process of working on the exhibition, we discovered a lot. And we found some paintings that were in the Hermitage, but we did not know that they were from the collection of Stanislav August. And now we managed to identify 20 paintings from his collection that are in the Hermitage.”

The Hermitage Theater does not lag behind the activities of the museum itself and presents new program"Living Masterpieces" Music, ballet, photography - on stage everything is united into one whole and stories on themes of antiquity, European and Russian art follow each other.

Pavel Yolkin, director St. Petersburg Theater ballet named after P.I. Tchaikovsky:

The significance of this project is that it is endless. That’s how many masterpieces there are in the Hermitage, that’s how many choreographic numbers we can stage, that’s how many masterpieces we can highlight that are in the Hermitage. And what’s great about this project is that it’s endless.”

According to tradition, the Hermitage will take an active part in the work of the international cultural forum, which will begin next week. The General Headquarters will become the central platform of the forum. An exhibition will open here, which will present models of all the first objects that were included in the UNESCO list. The forum itself is dedicated to the seventieth anniversary of this organization. Special attention will be devoted to the round table “80th anniversary of the adoption of the Roerich Pact.”

Mikhail Piotrovsky, CEO State Hermitage:

"We hope that in the modestly named round table “Roerich Pact” the most current issues related to the protection of museum collections in different conditions: war, disputes and everything else. We will host Italy Day, where two ministers of culture will discuss the problems of culture and economics using the example of the Italian experiment and the Russian experiment, and we will present materials related to the Hermitage understanding."

By the way, the Hermitage invited the townspeople to come up with a new name for the museum in the General Staff Building. The fact is that only the eastern wing belongs to the Hermitage. And in the English version the word headquarters does not quite accurately convey its meaning; it is rather associated with various services. Among the already proposed options, the leaders so far are “Hermitage of Russia” and “East Wing”.

Igor Tsyzhonov. Maxim Belyaev. Tatiana Osipova. Alexander Vysokikh and Andrey Klemeshov. First channel. Petersburg.

- Alexander the Great. Path to the East. Exhibition catalog / Scientific. ed. A. A. Trofimova. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2007. – 512 p.

- Alexander the Great. The life of an image in world culture. Collection of materials from the round table / Scientific. ed. A. A. Trofimova // Proceedings of the State Hermitage. T. LXIII. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2012. – 136 p.

- Andreev Yu. V. Greeks and barbarians in the Northern Black Sea region // VDI, No. 1. 1996. – P. 3–17.

- Antique sculpture Chersonese. – Kyiv: Mistetstvo, 1976. – 344 p.

- Ancient cities Northern Black Sea region: collection. articles // Essays on history and culture. I. – M.-L.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1955. – 448 p.

- Blavatsky V.D. Ancient archeology and history. – M.: Nauka, 1985. – 282 p.

- Bukina A.G. Exhibitions of antique painted vases of the Imperial Hermitage // Communications of the State Hermitage. 2014. T. LXXII. – pp. 213–230.

- Butyagin A. M. Myrmek expedition // Expeditions. Archeology in the Hermitage. – St. Petersburg: Slavia, 2014. – pp. 110–121.

- Vakhtina M. Yu. Greek art and the art of European Scythia // Greeks and barbarians of the Northern Black Sea region in the Scythian era. – St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2005. – P. 297–397.

- Vinogradov Yu. A. Cimmerian Bosporus // Greeks and barbarians of the Northern Black Sea region in the Scythian era. – St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2005. – P. 211–296.

- Herziger D.S. Antique fabrics in the Hermitage collection // Monuments of ancient applied art. – L.: Aurora, 1973. – P. 71–100.

- Grach N. L. Necropolis of Nymphaeum. – St. Petersburg: Nauka, 1999. – 328 p.

- Greeks and barbarians of the Northern Black Sea region in the Scythian era / Rep. ed. K. K. Marchenko. – St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2005. – 460 p.

- Greeks and barbarians at the Eurasian crossroads // Proceedings of the international conference “Bosporan phenomenon”. – St. Petersburg: Nestor-history, 2013. – pp. 181–194.

- Davydova L. I. Bosporan tombstone reliefs of the 5th century. BC e. – III century n. e. Exhibition catalogue. – L.: Publishing house of State University, 1990. – 127 p.

- Domansky Ya. V., Zuev V. Yu., Ilyina Yu. I., Marchenko K. K., Nazarov V. V., Chistov D. E. Materials of the Berezan (Nizhnebug) ancient archaeological expedition. T. I. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2006. – 229 p.

- Ancient city of Nymphaeum. Exhibition catalogue. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 1999. – 138 p.

- Ivanova A.P. Sculpture and painting of the Bosporus. – Kyiv: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, 1961. – 148 p.

- Kalashnik Yu. P. Greek gold in the Hermitage collection. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2014. – 280 p.

- Knipovich T. N. Main lines of development of art in ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea region // Antique cities of the Northern Black Sea region: collection. articles / Essays on history and culture. I. – M.-L.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1955. – P. 356–392.

- Kallistov D.P. Essays on the history of the Northern Black Sea region of the ancient era. – L.: Leningrad State University Publishing House, 1949. – 287 p.

- Kobylina M. M. Antique sculpture of the Northern Black Sea region. – M.: Nauka, 1972. – 60 p.

- Mantsevich A.P. Kurgan Solokha. – L.: Art, 1987. – 143 p.

- Neverov O. Ya. Antique intaglios in the Hermitage collection. – L.: Aurora, 1976. – 364 p.

- Antique cameos in the Hermitage collection: catalog / Enter. article and comp. O. Ya. Neverova. – L.: Art, 1988. – 192 p.

- Nikulina I.I., Andreeva E.M. On the history of the receipt and restoration of the statue of Dionysus // State Hermitage Reports. 2013. LXXI. – P. 74–83.

- Rostovtsev M.I. Antique decorative painting in the south of Russia. – St. Petersburg: Publication of the Imperial Archaeological Commission, 1913–1914.

- Savostina E. A. Hellas and Bosporus. Greek sculpture on the Northern Pontus / Bosporan Studies. Supplementum 8. – Simferopol – Kerch: Publishing House“Adef”, 2012. – 392 p.

- Sokolov G.I. Art of the Bosporan Kingdom. – M.: Publishing house MPEI, 1999. – 532 p.

- Trofimova A. A. Imitatio Alexandri. Portraits of Alexander the Great and mythological images in Hellenistic art. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2012. – 319 p.

- Trofimova A. A. Re-exposition program of the Department ancient world State Hermitage // Proceedings of the State Hermitage. L. Museums of the world in the 21st century. Restoration, reconstruction, re-exposition: materials of the International Conference / Scientific. ed. A. A. Trofimova. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2010. – pp. 67–81.

- Farmakovsky B.V. Archaic period in Russia // Materials on the archeology of Russia. No. 34. – Pgr., Printing house of the Main Directorate of Udelov, 1914. – P. 15–78.

- Chistov D. E., Zuev V. Yu., Ilyina Yu. I., Kasparov A. K., Novoselova N. Yu. Materials of the Berezan (Nizhnebug) ancient archaeological expedition. T. 2. Research on Berezan Island in 2005–2009. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2012. – 297 p.

- Hellenistic studies in the Hermitage. To the sixtieth birthday of M. B. Piotrovsky. Sat. articles / Scientific. ed. E. N. Khoza. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2004. – 196 p.

- Anthony Gormley. Full height. Antique and modern sculpture. Exhibition catalogue. State Hermitage Museum/ Scientific ed. D. Ozerkov, A. Trofimova. – St. Petersburg: Publishing house of State University, 2011. – 128 p.

- Bieber M. The Sculpture of the Hellenistic Age. Rev. ed. – New York: Columbia University Press, 1961. – 259 p., ill.

- Blawatsky W. Greco-Bosporan and Scythian Art // Encyclopaedia of World Art. London, 1962. – Vol. VI. – P. 862–865.

- Blavatsky V. D. Greco-bosporani e scitici centri // Encyclopedia Universale dell’arte. Roma, 1961. – Vol. VI. – P. 766–783.

- Boardman J. The Greeks Overseas. – Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1964. – 288 p.

- Boardman J. The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. – Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. – 352 p.

- Bukina A., Petrakova A., Phillips C. Greek Vases in the Imperial Hermitage Museum: The History of the Collection 1816–69 with Addenda et Corrigenda to Ludolf Stephani, Die Vasen-Sammlung der Kaiserlichen Eremitage (1869) // Beazley Archive, University of Oxford Studies in the History of Collections 4. – Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013. – 317 p.

- Burn. L. Hellenistic Art. From Alexander the Great to Augustus. – London; Los Angeles, 2004. – 190 p.

- Charbonneaux J., Martin R., Villard F. Hellenistic Art. – London: Thames and Hudson, 1973. – 430 p.

- Gombrich E. H. Art and Illusion. A Study of the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. – London: Phaidon Press, 1977. – 387 p.

- Greeks on the Black Sea. Ancient Art from the Hermitage / A. Trofimova (ed.) – Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007. – 384 p.

- Haskell F., Penny N. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture.1500–1900. – New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1981. – 376 p.

- Havelock C. M. Hellenistic Art: The Art of the Classical World from the Death of Alexander the Great to the Battle of Actium. – New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1981. – 283 p.

- History of Restoration of Ancient Stone Sculpture. Paper of the Symposium / J. Grossman, J. Podany, M. Treu (eds.). – Los Angeles: Getty publication, 2003. – 286 p.

- The Immortal Alexander the Great. The Myth. The Reality. His Journey. His Legacy. Catalog of the exhibition / A. Trofimova (ed.) – Amsterdam: Stichting Winkel de Nieuwe Kerk, 2010. – 302 p.

- Alexander the Great. 2000 years of treasures. Catalog of the exhibition / A. Trofimova (ed.) – Sydney: Australian Museum, 2012. – 297 p.

- Kaschnitz von Weinberg. G. Die mittelmeerischen Grundlagen der antiken Kunst. – Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann, 1944. – 84 S.

- Kaschnitz von Weinberg G. Römische Kunst. Heintze H. von (hrsg.). 4 Bande. – Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1961–1963. – 142; 144; 135; 123 pp.

- Krahmer G. Stilphasen der hellenistischen Plastik. – Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, 1924. – 47 p.

- Kunina N. Ancient Glass in the Hermitage Collection. – Saint Petersburg: Ars Publishers Ltd., 1997. – 339 p.

- Marshak B. Legends, Tales and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana. – New York: Bibliotheca Persica, 2002. – 187 p.

- Neverov O. The Lyde Brown collection and the History of Ancient sculpture in the Hermitage museum // American Journal of Archaeology. – Vol. 88. – No. 1 (Jan., 1984). – P. 33–42.

- Panofsky E. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art. – New York: Harper and Row, 1972. – 242 p.

- Panofsky E. Meaning in the Visaul Arts. – Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983. – 384 p.

- Petrakova A., Shuvalova O. Attic vases from the Campana collection in the State Hermitage museum: old restorations and present attitude regarding their exhibiting, study and conservation // Proceedings of the conference: L’Europe du vase antique: collectionneurs, savants, restaurateurs aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. – Paris, 2013. – P. 253–270.

- Pollitt J. J. Art in the Hellenistic Age. – Cambridge - London - New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986. – 329 p.

- Ridgway B. S. Hellenistic Sculpture. Vol. I. The Styles of ca. 331–200 B.C. – Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1990. – 405 p.

- Ridgway B. S. Hellenistic Sculpture. Vol. II. The Styles of ca. 200–100 B.C. – Madison, Wis.: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. – 456 p.

- Ridgway B. S. Hellenistic Sculpture. Vol. III. The Styles of ca. 100–31 B.C. – Madison, Wis.: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2002. – 456 p.

- Rostowzew M. I. Skythien und der Bosporus: Kritische über der schriftlichen und archäologischen quellen. – Berlin: H. Schoetz & Co., Gmbh., 1931. – 651 S.

- Trofimova A. “Imitatio Alexandri” in the Hellenistic Art. – Rome, L’ERMA di Bretschneider, 2012. - 190 p.

- Schlumberger D. L’Orient hellenisé. – Paris: A. Michel, 1970. – 247 p.

- Sedlmayer H. Kunst und Wahrheit: zur Theorie und Methode der Kunstgeschichte. – Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1958. – 210 p.

- Smith R. R. R. Hellenistic Royal Portraits. – Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. – 216 p.

- Smith R. R. R. Hellenistic Sculpture. – New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991. – 287 p.

- Solovyov S. L. Ancient Berezan: The Architecture, History and Culture of the First Greek Colony in the Northern Black Sea // Colloquia Pontica. – Vol. 4. – Leiden - Boston - Cologne: Brill Academic Publ., 1999. – 148 p.

- Stewart A. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. Vol. I–II. – New Haven - London: Yale University Press, 1990. – Vol. I. – 380 p., Vol. II – 800 p.

- Stewart A. Art in the Hellenistic World. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. –371 p.

- Trésors antiques: Bijoux de la collection Campana / F. Gaultier, C. Metzger. – Paris: 5. Continents editions, 2005. – 191 p.

- Waldhauer O. Ancient marbles in the Moscow Historical Museum // The Journal of Hellenic Studies. – 1924. – 44. – Part 1. – P. 45–54.

- Webster T. B. L. Hellenistic Poetry and Art. – London: Barnes & Noble, 1964. – 321 p.

- Wölfflin H. Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Das Problem der Stilentwickelung in der neueren Kunst. – München, F. Bruckmann a.-g., 1915. – 255 p.

- Zhizhina N. (Jijina N. C.) Wooden Sarcophagi with Plaster-Cast Appliqués from Nymphaeum // Northern Pontic Antiquities in the State Hermitage museum / J. Boardman, Sergei L. Solovyov, Gocha R. Tsetskhladze. Colloquia pontica. Vol. 7. – Leiden - Boston - Köln, 2001. – P. 249–264.

program "Journey to the Hermitage" leads from St. Petersburg studio "Radio Russia" Anna Vsemirova.

Last week, a girl appeared in the Roman courtyard of the New Hermitage wearing a light chiton that emphasized the curves of her slender figure. Hair flows freely over the shoulders. The stranger's head is decorated with a tiara, earrings in her ears, and a bracelet on her hand. The eyes radiate joy, and there is a slight smile on the lips. We had long dreamed of her arrival at the Hermitage. Ministers and ambassadors arrived to greet her. Despite her age (6th century BC), she is young and beautiful. This is an archaic statue of a girl from the Greek Acropolis. Her arrival at the Hermitage marked the beginning of the Year of Greece in Russia.

Opening the ceremony, the director of the Hermitage Mikhail Piotrovsky noted.

M. Piotrovsky: This is one of the two best surviving statues that were offered to the goddess Athena, a statue that symbolizes Greek art when that era began. Magna Graecia, from which comes everything that we call our culture and civilization: from political theories to poetry and artistic language. This amazing masterpiece stands here in the Roman courtyard of the New Hermitage, in a setting in which greek sculpture was exhibited in the 19th century, becoming such a model of beauty for Europe. Nearby, in Russian Museum, big exhibition Leona Baksta, and there famous painting "Ancient horror" (lat. "Terror Antiquus") , where there is also such a bark with its smile. This smile can be called differently. For Europe, this is then the smile of Gioconda, and you can see this smile in the halls of the Hermitage displaying Italian art.

The bark itself also represents the assimilation of ancient cultures of the Middle East, and their development in Greece, because it is similar to ancient egyptian sculptures, and, in general, causes a lot of different different thoughts, although in fact it still causes delight. This is one of the most beautiful things ever created by people on Earth. And this is exactly how we treat her with the most respect and admiration.

It is my pleasure to give the floor to the President of the Acropolis Museum, Mr. Dimitrios Pandermalis.

D. Pandermalis: This statue with such a characteristic smile symbolizes the joy of life and hope for the future. This lovely girl is absolutely happy that she left the Athens museum for a while to decorate this museum with her youthful beauty. greatest museum peace. It seems to me that this statue will fit perfectly into these premises of the Hermitage with an amazing collection of Roman and Greek sculptures.

Archaic statues of kor, a bark in Greek means "young woman", is one of the most exquisite creations in the history of ancient Greek sculpture. Marble statues, depicting attractive girls in elegant clothes and jewelry, it was customary to bring as a gift to the temples of Athena, so that with their youthful appearance, beauty and energy they would please the goddess.

In total, archaeologists found about 200 cors on the Acropolis. In other sanctuaries, statues of young men - kouros - predominate. Kor statues were freely placed in the temple of Athena and nearby on the Acropolis. There were inscriptions on the pedestals and columns with the names of the donors. Archaic is the name given to the stage of early Greek history of art and culture. It is significant for ancient civilization as a whole. It was during the Archaic era that democracy, theater, poetry arose in ancient society, and Greek writing took shape. And this is what I emphasized Mikhail Shvydkoy, Special Representative of the President of the Russian Federation for International Cultural Cooperation.

M. Shvydkoy: It is symbolic that the Greek Year in Russia opens in St. Petersburg, because here he was formed as a great political figure Count Kapodistrias, who was the manager of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Russian Empire, and then became the first ruler of Greece in Greece, which was freed from Ottoman Empire. IN highest degree it is important that this happens here, in the Hermitage, in the great Russian museum, which shaped many generations of both the Russian aristocracy and those people who served the Russian Empire.

On March 11, at the Acropolis Museum, we presented three Scythian masterpieces from the Hermitage. The Russian program of the Year of Russia in Greece was opened. And today the Year, one might say, began to work in its entirety. This Year is connected not only with culture, it also covers economics, politics, science, and education. Our Greek colleagues really showed consistency and a certain independence in holding the Year of the Cross with our country in the current rather difficult political circumstances. This year we also celebrate the millennium of Russian monasticism on Mount Athos. This is a completely special holiday, a special date, which, naturally, opens up deep connections between our two countries and cultures.

The Roman courtyard of the New Hermitage has its own collection of sculptures. But its central part is either free or given over to the most important works of art associated with antiquity from other museums. Thus, in 2014, for the 250th anniversary of the Hermitage, a sculpture of the Parthenon from the collection appeared in the Roman courtyard British Museum, depicting a river deity - an allegory of the Athenian river Ilissus.

Kora had also never left the Acropolis before. She talks about how her arrival in St. Petersburg was prepared. Anna Trofimova, head of the Hermitage's Antiquities Department.

A. Trofimova: The dream of archaic sculpture has literally haunted both our employees and me for many, many years, because we don’t have it in the museum. And we have long wanted to ask to somehow organize an exhibition of archaic sculpture. And then the Year of Greece in Russia happened. We have started this work. In the end, the Greeks agreed. We ourselves did not expect this. They never gave this sculpture to exhibitions. And it’s rare in general that the Acropolis Museum gives out its exhibits.

First there was talk about "Cycladic idol", but this was a proposal from the Greek side. Of course, this is also very interesting, but it immediately became clear to me that "Cycladic idol" will not meet our expectations. Our city is very classic. We, St. Petersburg residents, in general, are all children of antiquity. This is both the architecture and these halls. And, in addition, there was an exhibition by Ilissa.

They chose this bark. She is one of the most attractive and very sensual sculptures. And then she has a lot of paint. Therefore, I’m even glad that it was this bark that arrived, and not "Bark in Peplos", for example, or "Chios bark". This is a big event. All the Hermitage people are happy, everyone runs to look at her.

Although we are talking about archaic sculpture, sometimes fate is still favorable to works of art and the names of the sculptors are preserved there. Didn't save this one?

A. Trofimova: No. But it is very similar to the kouros that was found in Boeotia, in a sanctuary, and there are signatures of the sculptor Endois. Perhaps this is his workshop, his hand. We can say that this is a certain perfect image, and this is Endois's workshop.

A marble archaic bark statue was found in 1886 on the Athenian Acropolis near the Erechtheion temple. We must remember that all the monuments and temples erected on the Acropolis were dedicated to Athena. Athena Nike brought victory in battles, Athena Ergana was the patroness of artisans, Athena Parthenos personified chastity. The main religious festival of Athens was held in her honor. And over time, the Acropolis was filled with dedications to Athena.

Most of the dedications of the archaic Acropolis have not reached our time due to tragic episodes of history. During the Greco-Persian Wars in 480 BC, the Persians penetrated the once impregnable hilltop. The temples of the Acropolis were destroyed, statues were broken or burned. After the Persians left, the Athenians, restoring the defensive walls, began to clear the Acropolis of rubble. But they buried all the damaged sculptures, pedestals, and architectural fragments near one of the old walls, thus possibly strengthening the wall on the hillside. And it was thanks to this burial, which archaeologists list as “Persian garbage,” that two and a half millennia later magnificent sculptures were found. Here are the ancient ones preserved on them bright colors. Then it completely changed previous ideas about ancient art. Moreover, the draperies of the kor girls’ clothes, despite their external similarity, amaze with their diversity and imitation of embroidery. Each bark in an outstretched hand bore its gift to the goddess Athena. It could be a wreath, a pomegranate or a bird.

Continues the story Anna Trofimova

A. Trofimova: Moreover, I would say that each cortex is an individual. These are not only features of the face and figure, but also, of course, details of clothing and jewelry. Different people reconstruct her headdress in different ways. Professor Brinkmann (Germany) believes that she had rays. It turns out to be somewhat Martian in appearance. Well, how are you? Helios. Professor Pandermalis showed me a metal tiara with lotuses. And this, of course, looks more organic. Basically, the crusts are not large. One meter 50 centimeters is, so to speak, her average height. Our bark is 1 meter 15 centimeters tall. Very high "Cora Antenora" has a height of 2 meters 15 centimeters. In fact, this is due to the high cost. First of all, this determined the size of the sculpture. This is marble, and it is very lively and pleasant. In Russian, this is marble. At the same time, she has a fragment of her hand - this is an antique restoration, Pentelic marble. That's how interesting it is.

We saw ancient greek sculpture, sometimes they were inserted into their eyes gems. And the eyes of the bark?

A. Trofimova: We painted.

And what color?

A. Trofimova: Black. Sometimes the eyes were blue, but it was absolutely certain that the pupil was black and the eyelashes were black.

Could the belt and tunic have azure outlines?

A. Trofimova: Yes. There was a bright coloring book. The bark usually has a light skirt, sometimes it was painted, but most often the top was painted, and the bottom remained light. And such stars in the form of snowflakes are scattered throughout the bark.

Did the cors have sandals?

A. Trofimova: They are wearing sandals. They have very sophisticated thin fingers, worked out.

Should the bark be worn?

A. Trofimova: Must be dressed.

“Art is both very human and eternal,” the French sculptor wrote about the archaic at the beginning of the 20th century Emile Antoine Bourdelle. Many viewers get this feeling. One of the walls of the Roman courtyard of the New Hermitage is equipped with a screen on which the history of the Acropolis and the “daughters of the Acropolis” is told. So today in scientific world they talk about barks. Reconstruction on the screen allows you to see color solutions clothes. But what kind of restoration intervention in archaic sculpture do Greek specialists allow?

Ends the conversation Anna Trofimova, head of the Hermitage’s department of ancient history.

A. Trofimova: I think they are conservative, just like us. And this is good. They will not paint the sculpture. This is a question that faces them everywhere. After all, they are now restoring the Parthenon, not just anything, they are restoring many parts. As for the coloring, of course, they are not reconstructing it. They restore delicately. After all, the essence of these sculptures is also their unique feature is that a lot has been preserved on them. Typically, archaic sculpture does not have such traces. They are simply washed away by the rain. After all, these were paints of organic origin. But these were buried, they were in the ground, and therefore they retained their colors. So what you see is not the result of a restorer’s work, it’s paint.

An archaic bark statue will remain in the Roman courtyard of the New Hermitage until October. There is time to get to know each other.

Listen to the entire program in the audio file of the program.