Greek sculpture. Sculptural and architectural features of ancient Greece

Since I will soon have to give a course of lectures on the general history of art, I am preparing and repeating the material. I decided to post some of it and my thoughts on this subject. This is not the lecture itself, but thoughts on a narrow specific topic.It is difficult to overestimate the place of sculpture in the art of Antiquity. However, its two most important national manifestations - the sculpture of Ancient Greece and the sculpture of Ancient Rome - represent two completely different, in many ways opposite phenomena. What are they?

The sculpture of Greece is truly famous and should in fact be ranked first compared to Greek architecture. The fact is that the Greeks perceived architecture itself as sculpture. For a Greek, any building is, first of all, a plastic volume, a monument, perfect in its forms, but intended primarily for contemplation from the outside. But I will write about architecture separately.

The names of Greek sculptors are well known and heard by everyone who went to school. The Greek easel painters were just as famous and renowned, however, as sometimes happens in the history of art, nothing at all has survived from their works, well, perhaps, supposed copies on the walls of the houses of rich Romans (as can be seen in Pompeii). However, as we will see, the situation is not so good with the originals of Greek statues, since most of them are known, again, from Roman replicas devoid of Greek perfection.

However, with such attentive attention to the names of the creators of art, the Greeks remained completely indifferent to individuality, to what would now be called the personality of a person. Having made man the center of their art, the Greeks saw in him a sublime ideal, a manifestation of perfection, a harmonious combination of soul and body, but were not at all interested in the particular characteristics of the person depicted. The Greeks did not know the portrait in our understanding of the word (with the possible exception of the later, Hellenistic period). By erecting statues of humanoid gods, heroes, famous citizens of their polis, they created a generalized, typical image that embodied the positive qualities of the soul, heroism, virtue and beauty.

The worldview of the Greeks began to change only with the end of the classical era in the 4th century BC. The end of the old world was put by Alexander the Great, whose unprecedented activity gave birth to the cultural phenomenon of mixing Greek and Middle Eastern, which was called Hellenism. But only after more than 2 centuries, Rome, already powerful by that time, entered the arena of art history.

Oddly enough, but for a good half (if not most) of its history, Rome showed almost nothing of itself from an artistic point of view. This is how almost the entire republican period passed, remaining in the memory of the people as a time of Roman valor and purity of morals. But finally, in the 1st century BC. Roman sculptural portrait arose. It is difficult to say how great the role of the Greeks, who were now working for the Romans who conquered them, was in this. It must be assumed that without them Rome would hardly have created such brilliant art. However, no matter who created Roman works of art, they were exactly Roman.

Paradoxically, although it was Rome that created what may be the most individual art of portraiture in the world, no information has been preserved about the sculptors who created this art. Thus, the sculpture of Rome and, above all, the sculptural portrait is the opposite phenomenon to the classical sculpture of Greece.

It should be immediately noted that another, this time local, Italian tradition, namely the art of the Etruscans, played an important role in its formation. Well, let's look at the monuments and use them to characterize the main phenomena in ancient sculpture.

Already in this marble head from the Cyclades Islands 3 thousand BC. e. laid down that plastic feeling that would become the main asset of Greek art. This is not harmed in any way by the minimalism of the details, which of course was complemented by painting, since until the high Renaissance, sculpture was never colorless.

A well-known (well, this can be said about almost any statue by a Greek sculptor) group depicting the tyrone killers Harmodius and Aristogeiton, sculpted by Critias and Nesiot. Without being distracted by the formation of Greek art in the archaic era, we have already turned to the classics of the 5th century. BC. Representing two heroes, fighters for the democratic ideals of Athens, the sculptors depict two conventional figures, only in general terms similar to the prototypes themselves. Their main task is to combine into a single whole two beautiful, ideal bodies, captured by one heroic impulse. Bodily perfection here implies the inner rightness and dignity of those depicted.

In some of their works, the Greeks sought to convey the harmony contained in peace, in statics. Polykleitos achieved this both through the proportionation of the figure and through the dynamics contained in the positioning of the figure. T.n. chiasmus or otherwise contrapposto - the oppositely directed movement of different parts of a figure - one of the conquests of this time, forever embedded in the flesh of European art. The originals of Polykleitos have been lost. Contrary to the custom of the modern viewer, the Greeks often worked by casting statues in bronze, which avoided the obstructive stands that arose in the marble repetitions of Roman times. (On the right is a bronze copy-reconstruction from the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, how much better it is!)

Myron became famous for conveying very complex states in which peace is about to give way to active movement. Again, I present two versions of his discus thrower (both late): marble and bronze.

“Rublev” of Ancient Greece, the great creator of the sculpture of the Athenian Acropolis, Phidias, on the contrary, achieved beauty and balance even in the most intense and moving compositions. Here we have the opportunity to see the originals of the 5th century. BC, this time made of marble as related to the flesh of the Parthenon architecture. Even in its broken form, without arms, legs and heads, in the form of pitiful ruins, the Greek classics are amazingly perfect. No other art could do this.

What about the portrait? Here is a famous image of the great Pericles. But what can we learn from it about this man? Only that he was a great citizen of his city, an outstanding figure and a valiant commander. And nothing more.

The “portrait” of Plato was solved differently, no longer presented as a young sage with a bushy beard and an intellectual, mentally tense face. The loss of eye painting, of course, largely deprives the image of expression.

The image was already perceived differently at the end of the 4th century. The surviving replicas of the portraits of Alexander the Great created by Lysippos show us a personality that is no longer as integral, confident and unambiguous as we just saw in the classical period of Greece.

Now, finally, the time has come to move on to Rome, or rather, for now, to the Etruscans, who created funerary images of the deceased. The Etruscans made canopic urns - urns for ashes - with images of heads and hands, likening them, so far conditionally, to a deceased person. Terracotta canopic jar from the 6th century BC. e.

More complex works were such tombstones with figures of people, often married couples, reclining as if at a feast.

Charming smiles, similar to the smiles of archaic Greek statues... But something else is important here - these are specific people buried here.

Etruscan traditions laid a kind of foundation for the Roman portrait itself. Having emerged only in the 1st century BC, the Roman portrait was sharply different from any other. The primary thing in it was the authenticity in conveying the truth of life, the unembellished appearance of a person, the portrayal of him as he is. And in this the Romans undoubtedly saw their own dignity. The term verism can best be applied to the Roman portrait of the end of the republican era. He even frightens with his repulsive frankness, which does not stop at any features of ugliness and old age.

To illustrate the following thesis, I will give an encyclopedic example - images of a Roman in a toga with portraits of his ancestors. In this obligatory Roman custom there was not only a human desire to preserve the memory of bygone generations, but also a religious component, so typical for such a domestic religion as the Roman one.

Following the Etruscans, the Romans depicted married couples on their tombstones. In general, plastic arts and sculpture were as natural for a resident of Rome as photography is for us.

But now a new time has come. At the turn of the millennium (and eras) Rome became an empire. From now on, our gallery will be represented primarily by portraits of emperors. However, this official art not only preserved, but also increased the extraordinary realism that originally appeared in Roman portraiture. However, first in the era of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD), Roman art experienced its first serious interaction with the ideal beauty inherent in everything Greek. But even here, having become perfect in form, it remained faithful to the portrait features of the emperor. By allowing convention in a perfect, ideally regular and healthy body, dressed in armor and in a ceremonial pose, Roman art places on this body the real head of Augustus, as he was.

An amazing mastery of stone processing passed from Greece to the Romans, but here this art could not obscure what was inherently Roman.

Another version of the official image of Augustus as the Great Pontiff with a veil thrown over his head.

And now, already in the portrait of Vespasian (69 - 79 AD) we again see overt verism. This image has stuck in my memory since childhood, captivating me with the personal features of the depicted emperor. An intelligent, noble and at the same time cunning and calculating face! (How does a broken nose suit him))

At the same time, new marble processing techniques are being mastered. The use of a drill allows you to create a more complex play of volumes, light and shadow, and introduce contrast of different textures: rough hair, polished skin. For example, a female image, otherwise until now we have only presented men.

Trojan (98 - 117)

Antoninus Pius was the second emperor after Hadrian to grow a beard in the Greek style. And this is not just a certain game. Along with the “Greek” appearance, something philosophical also appears in the image of a person. The gaze goes to the side, upward, depriving a person of a state of balance and contentment with the body. (Now the pupils of the eyes are outlined by the sculptor himself, which preserves the look even if the former tinting is lost.)

This is clearly evident in the portraits of the philosopher on the throne - Marcus Aurelius (161 - 180).

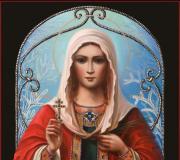

This interesting fragment attracts me for this reason. Try to draw facial features and you will get an icon! Take a closer look at the shapes of the eye, eyelid, pupil and compare them with Byzantine icons.

But the valiant and righteous should not be the subject of a Roman portrait alone! Heliogabalus (correctly - Elagabalus), an adherent of the eastern cult of the sun, surprised the Romans with customs that were completely disgusting to them and did not shine with the purity of life. But this too clearly shows us his portrait.

Finally, the golden age of Rome is far behind us. The so-called soldier emperors are being enthroned one after another. People from any class, country or people can suddenly become rulers of Rome, being proclaimed by their soldiers. Portrait of Philip the Arabian (244 - 249), not the worst of them. And again there is some kind of melancholy or anxiety in the look...

Well, this is funny: Trebonian Gall (251 - 253).

Here it is time to note what appeared from time to time in Roman portraits before. Now the form begins to inexorably become schematized, plastic modeling gives way to conventional graphics. The flesh itself gradually disappears, giving way to a purely spiritual, exclusively internal image. Emperor Probus (276 - 282).

And now, we have approached the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th centuries. Diocletian creates a new system of governing the Empire - the tetrarchy. Two Augusts and two Caesars rule over its four parts. The old city of Rome, which has long lost its role as the capital, is no longer important. A funny group of four almost identical figures, identified with the tetrarchs, was preserved in Venice, taken from Constantinople. It is often shown as the end of a Roman portrait. But that's not true! In fact, this is, let’s say, a special experiment, the avant-garde of that time. Moreover, according to some of my teachers, this is an Egyptian work, which is particularly evident from the use of hard porphyry. The metropolitan Roman school remained, of course, different and did not die for at least another century.

In confirmation of what has been said, another image from Egypt is the emperor Maximin Daza (305 - 313). Complete stylization, schematization and abstraction, if you like.

But what continued to happen in Rome. Constantine the Great (306 - 337) becomes the sovereign ruler of the Empire. In his colossal-scale portrait (this, in fact, is the head of the Colossus - a giant statue installed in the Roman Basilica of Constantine-Maxentius) there is fully present both an ideal, perfect elaboration of the form and a finally formed new image, detached from everything temporary. In the huge, beautiful eyes looking somewhere past us, strong-willed eyebrows, a hard nose, closed lips, now there is not only the image of an earthly ruler, but also something that has already crossed the boundaries of that reflection that consumed Marcus Aurelius and his other contemporaries, who were burdened this bodily shell in which the soul is enclosed.

If the famous Edict of Milan in 313 only stopped the persecution of Christianity, allowing Christians to legally exist in the Empire (Constantine himself was baptized only at death), then by the end of the 4th century after Christ, Christianity had already become dominant. And at this time of Christian Antiquity, sculptural portraits continued to be created. The portrait of Emperor Arcadius (383-408) amazes with its beauty, but also with its unearthly abstraction.

This is where the Roman portrait ultimately came, this is the image it gave birth to, becoming Christian art in itself. Sculpture is now giving way to painting. But the great heritage of the previous culture is not rejected, continuing to live, serving new goals and objectives. The Christian image (icon), on the one hand, was born from the words: “No one has ever seen God; He has revealed the Only Begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father” (John 1:18). On the other hand, he absorbed all the experience of the art that preceded him, as we saw, which had long been painfully searching for the truth, and finally found It.

But that's a completely different story, not for this story...

Zeus was the king of the gods, the god of the sky and weather, law, order and fate. He was depicted as a regal man, mature with a strong figure and a dark beard. His usual attributes were lightning bolts, a royal scepter and an eagle. Father of Hercules, organizer of the Trojan War, fighter against the hundred-headed monster. He flooded the world so that humanity could begin to live again.

Poseidon was the great Olympian god of the sea, rivers, floods and droughts, earthquakes, and also the patron of horses. He was depicted as a mature man of strong build with a dark beard and holding a trident. When Chron divided the world between his sons, he received rule over the sea.

Demeter was the great Olympian goddess of fertility, agriculture, grain, and bread. She also presided over one of the mystery cults that promised their initiates a path to a blessed afterlife. Demeter was depicted as a mature woman, often crowned, holding ears of wheat and a torch. She brought famine to Earth, but she also sent the hero Triptolemos to teach people how to cultivate the land.

Hera was the queen of the Olympian gods and the goddess of women and marriage. She was also the goddess of the starry sky. She is usually depicted as a beautiful woman wearing a crown, holding a royal staff with a lotus tip. She sometimes keeps a royal lion, cuckoo or hawk as companions. She was the wife of Zeus. She gave birth to a crippled baby, Hephaestus, whom she threw from Heaven with just a glance. He himself was the god of fire and a skilled blacksmith and patron of blacksmithing. In the Trojan War, Hera helped the Greeks.

Apollo was the great god of Olympian prophecies and oracles, healing, plague and disease, music, song and poetry, archery, and protection of the young. He was depicted as a handsome, beardless youth with long hair and various attributes, such as a wreath and laurel branch, a bow and quiver, a crow, and a lyre. Apollo had a temple at Delphi.

Artemis was the great goddess of the hunt, wilderness and wild animals. She was also the goddess of childbirth and the patroness of young girls. Her twin, Apollo's brother, was also the patron saint of teenage boys. Together, these two gods were also the agents of sudden death and disease - Artemis targeting women and girls, and Apollo targeting men and boys.

In ancient art, Artemis is usually depicted as a girl, dressed in a short chiton that reaches her knees and equipped with a hunting bow and a quiver of arrows.

After her birth, she immediately helped her mother give birth to her twin brother, Apollo. She turned the hunter Actaeon into a deer when he saw her bathing.

Hephaestus was the great Olympian god of fire, metalworking, stonemasonry, and the art of sculpture. He was usually depicted as a bearded man with a hammer and tongs, the tools of a blacksmith, and riding a donkey.

Athena was the great Olympian goddess of wise counsel, war, city defense, heroic efforts, weaving, pottery and other crafts. She was depicted crowned with a helmet, armed with a shield and spear, and wearing a cloak trimmed with a snake wrapped around her chest and arms, adorned with the head of a Gorgon.

Ares was the great Olympian god of war, civil order and courage. In Greek art, he was depicted as either a mature, bearded warrior dressed in battle armor, or a naked, beardless youth with a helmet and spear. Due to its lack of distinctive features, it is often difficult to identify in classical art.

Ancient Greek sculpture is the leading standard in world sculptural art, which continues to inspire modern sculptors to create artistic masterpieces. Frequent themes of sculptures and stucco compositions of ancient Greek sculptors were the battles of great heroes, mythology and legends, rulers and ancient Greek gods.

Greek sculpture received particular development in the period from 800 to 300 BC. e. This area of sculptural creativity drew early inspiration from Egyptian and Middle Eastern monumental art and evolved over the centuries into a uniquely Greek vision of the form and dynamics of the human body.

Greek painters and sculptors achieved the pinnacle of artistic excellence that captured the elusive features of a person and showcased them in a way that no one else had ever been able to show. Greek sculptors were particularly interested in proportion, balance, and the idealized perfection of the human body, and their stone and bronze figures became some of the most recognizable works of art ever produced by any civilization.

The Origin of Sculpture in Ancient Greece

From the 8th century BC, archaic Greece saw an increase in the production of small solid figures made of clay, ivory and bronze. Of course, wood was also a widely used material, but its susceptibility to erosion prevented wooden products from being mass-produced as they did not exhibit the necessary durability. Bronze figures, human heads, mythical monsters, and in particular griffins, were used as decoration and handles for bronze vessels, cauldrons and bowls.

In style, Greek human figures have expressive geometric lines, which can often be found on pottery of the time. The bodies of warriors and gods are depicted with elongated limbs and a triangular torso. Also, ancient Greek creations are often decorated with animal figures. Many of them have been found throughout Greece at sites of refuge such as Olympia and Delphi, indicating their general function as amulets and objects of worship.

Photo:

The oldest Greek limestone stone sculptures date back to the mid-7th century BC and were found in Thera. During this period, bronze figures appeared more and more often. From the point of view of the author's plan, the subjects of the sculptural compositions became more and more complex and ambitious and could already depict warriors, scenes from battles, athletes, chariots and even musicians with instruments of that period.

Marble sculpture appears at the beginning of the 6th century BC. The first life-size monumental marble statues served as monuments dedicated to heroes and nobles, or were located in sanctuaries where symbolic worship of the gods was carried out.

The earliest large stone figures found in Greece depicted young men dressed in women's clothing, accompanied by a cow. The sculptures were static and crude, as in Egyptian monumental statues, the arms were placed straight at the sides, the legs were almost together, and the eyes looked straight ahead without any special facial expression. These rather static figures slowly evolved through the detailing of the image. Talented craftsmen emphasized the smallest details of the image, such as hair and muscles, thanks to which the figures began to come to life.

A characteristic posture for Greek statues was a position in which the arms are slightly bent, which gives them tension in the muscles and veins, and one leg (usually the right) is slightly moved forward, giving a sense of dynamic movement of the statue. This is how the first realistic images of the human body in dynamics appeared.

Photo:

Painting and staining of ancient Greek sculpture

By the early 19th century, systematic excavations of ancient Greek sites had revealed many sculptures with traces of multicolored surfaces, some of which were still visible. Despite this, influential art historians such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann objected so strongly to the idea of painted Greek sculpture that proponents of painted statues were labeled eccentrics and their views were largely suppressed for over a century.

Only the published scientific papers of the German archaeologist Windzenik Brinkmann in the late 20th and early 21st centuries described the discovery of a number of famous ancient Greek sculptures. Using high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, specially designed cameras, plaster casts and some powdered minerals, Brinkmann proved that the entire Parthenon, including the main part, as well as the statues, were painted in different colors. He then chemically and physically analyzed the original paint's pigments to determine its composition.

Brinkmann created several multi-colored replicas of Greek statues that were toured around the world. The collection included copies of many works of Greek and Roman sculpture, demonstrating that the practice of painting sculpture was the norm and not the exception in Greek and Roman art.

The museums in which the exhibits were exhibited noted the great success of the exhibition among visitors, which is due to some discrepancy between the usual snow-white Greek athletes and the brightly colored statues that they actually were. Exhibition venues include the Glyptothek Museum in Munich, the Vatican Museum and the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The collection made its American debut at Harvard University in the fall of 2007.

Photo:

Stages of the formation of Greek sculpture

The development of sculptural art in Greece went through several significant stages. Each of them was reflected in the sculpture with its own characteristic features, noticeable even to non-professionals.

Geometric stage

It is believed that the earliest incarnation of Greek sculpture was in the form of wooden cult statues, first described by Pausanias. No evidence of this survives, and descriptions of them are vague, despite the fact that they were likely objects of veneration for hundreds of years.

The first real evidence of Greek sculpture was found on the island of Euboea and dates back to 920 BC. It was a statue of a Lefkandi centaur by an unknown terracotta sculpture. The statue was collected in parts, having been deliberately broken and buried in two separate graves. The centaur has a distinct mark (wound) on his knee. This allowed researchers to suggest that the statue may depict Chiron wounded by the arrow of Hercules. If this is indeed true, this may be considered the earliest known description of the myth in the history of Greek sculpture.

The sculptures of the Geometric period (approximately 900 to 700 BC) were small figurines made of terracotta, bronze and ivory. Typical sculptural works of this era are represented by many examples of equestrian statues. However, the subject repertoire is not limited to men and horses, as some found examples of statues and stucco from the period depict images of deer, birds, beetles, hares, griffins and lions.

There are no inscriptions on early period geometric sculpture until the early 7th century BC statue of Mantiklos "Apollo" found at Thebes. The sculpture represents a figure of a standing man with an inscription at his feet. This inscription is a kind of instruction to help each other and return good for good.

Archaic period

Inspired by the monumental stone sculpture of Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Greeks began carving in stone again. The individual figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of oriental models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture. Examples of sculptures from this period are the statues of Lady Auxerre and the torso of Hera (early archaic period - 660-580 BC, exhibited in the Louvre, Paris).

Photo:

Such figures had one characteristic feature in their facial expression - an archaic smile. This expression, which has no specific relevance to the person or situation depicted, may have been the artist's tool to give the figures an animated, "live" quality.

During this period, sculpture was dominated by three types of figures: a standing naked youth, a standing girl dressed in traditional Greek attire, and a seated woman. They emphasize and summarize the main features of the human figure and show an increasingly accurate understanding and knowledge of human anatomy.

Ancient Greek statues of naked youths, in particular the famous Apollo, were often presented in enormous sizes, which was supposed to show power and masculine strength. These statues show much more detail of the musculature and skeletal structure than the early geometric works. The clothed girls have a wide range of facial expressions and poses, as in the sculptures of the Athenian Acropolis. Their drapery is carved and painted with the delicacy and care characteristic of the details of sculpture of this period.

The Greeks decided very early on that the human figure was the most important subject of artistic endeavor. It is enough to remember that their gods have a human appearance, which means that there was no difference between the sacred and the secular in art - the human body was both secular and sacred at the same time. A male nude without character reference could just as easily become Apollo or Hercules, or depict a mighty Olympian.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce sculpture just for artistic display. Statues were created to order, either by aristocrats and nobles, or by the state, and were used for public memorials, to decorate temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is often proven by ancient inscriptions on statues). The Greeks also used sculptures as grave markers. Statues in the Archaic period were not intended to represent specific people. These were images of ideal beauty, piety, honor or sacrifice. This is why sculptors have always created sculptures of young people, ranging from adolescence to early adulthood, even when they were placed on the graves of (presumably) older citizens.

Classical period

The Classical period brought a revolution in Greek sculpture, sometimes associated by historians with radical changes in socio-political life - the introduction of democracy and the end of the aristocratic era. The Classical period brought with it changes in the style and function of sculpture, as well as a dramatic increase in the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting realistic human forms.

Photo:

The poses also became more natural and dynamic, especially at the beginning of the period. It was during this time that Greek statues increasingly began to depict real people, rather than vague interpretations of myths or completely fictional characters. Although the style in which they were presented had not yet developed into a realistic portrait form. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, created in Athens, symbolize the overthrow of aristocratic tyranny and, according to historians, become the first public monuments to show the figures of real people.

The classical period also saw the flourishing of stucco art and the use of sculptures as decoration for buildings. Characteristic temples of the classical era, such as the Parthenon at Athens and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, used relief molding for decorative friezes and wall and ceiling decoration. The complex aesthetic and technical challenges faced by sculptors of that period contributed to the creation of sculptural innovations. Most of the works of that period have survived only in the form of individual fragments, for example, the stucco decoration of the Parthenon is today partly in the British Museum.

Funeral sculpture made a huge leap during this period, from the rigid and impersonal statues of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical era. These monuments are usually found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict “ideal” types of people (a yearning mother, an obedient son), they increasingly become the personification of real people and, as a rule, show that the deceased leaves this world with dignity, leaving his family. This is a noticeable increase in the level of emotions relative to the archaic and geometric eras.

Another noticeable change is the flourishing of the creativity of talented sculptors, whose names have gone down in history. All information known about sculptures in the Archaic and Geometric periods focuses on the works themselves, and rarely is attention given to their authors.

Hellenistic period

The transition from the classical to the Hellenistic (or Greek) period occurred in the 4th century BC. Greek art became increasingly diverse under the influence of the cultures of the peoples involved in the Greek orbit and the conquests of Alexander the Great (336-332 BC). According to some art historians, this led to a decrease in the quality and originality of the sculpture, although people of the time may not have shared this opinion.

It is known that many sculptures previously considered the geniuses of the classical era were actually created during the Hellenistic period. The technical ability and talent of Hellenistic sculptors is evident in such major works as the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Pergamon Altar. New centers of Greek culture, especially in sculpture, developed in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamon and other cities. By the 2nd century BC, the growing power of Rome had also absorbed much of the Greek tradition.

Photo:

During this period, sculpture again experienced a shift towards naturalism. The heroes for creating sculptures now became ordinary people - men, women with children, animals and domestic scenes. Many of the creations from this period were commissioned by wealthy families to decorate their homes and gardens. Lifelike figures of men and women of all ages were created, and sculptors no longer felt obligated to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.

At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities that arose in Egypt, Syria and Anatolia needed statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This led to sculpture, like ceramics, becoming an industry, with subsequent standardization and some decline in quality. That is why many more Hellenistic creations have survived to this day than the era of the classical period.

Along with the natural shift towards naturalism, there was also a shift in the expression and emotional embodiment of the sculptures. The heroes of the statues began to express more energy, courage and strength. A simple way to appreciate this shift in expression is to compare the most famous works created during the Hellenistic period with the sculptures of the classical phase. One of the most famous masterpieces of the classical period is the sculpture “The Carrier of Delphi”, expressing humility and submission. At the same time, the sculptures of the Hellenistic period reflect strength and energy, which is especially clearly expressed in the work “Jockey of Artemisia”.

The most famous Hellenistic sculptures in the world are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (1st century BC) and the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos, better known as the Venus de Milo (mid-2nd century BC). These statues depict classical subjects and themes, but their execution is much more sensual and emotional than the austere spirit of the classical period and its technical skills allowed.

Photo:

Hellenistic sculpture also underwent an increase in scale, culminating in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), which historians believe was comparable in size to the Statue of Liberty. A series of earthquakes and robberies destroyed this heritage of Ancient Greece, like many other major works of this period, the existence of which is described in the literary works of contemporaries.

After the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek culture spread to India, as shown by the excavations of Ai-Khanum in eastern Afghanistan. Greco-Buddhist art represented an intermediate stage between Greek art and the visual expression of Buddhism. Discoveries made since the late 19th century regarding the ancient Egyptian city of Heracles have revealed the remains of a statue of Isis dating back to the 4th century BC.

The statue depicts the Egyptian goddess in an unusually sensual and subtle way. This is uncharacteristic of the sculptors of that area, because the image is detailed and feminine, symbolizing the combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms during the time of Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt.

Ancient Greek sculpture is the progenitor of all world art! Until now, the masterpieces of Ancient Greece attract millions of tourists and art connoisseurs who want to touch the timeless beauty and talent.

Antique sculpture

HERMITAGE

Aphrodite

Aphrodite

Aphrodite (Venus Tauride)

Description:

According to Hesiod’s “Theogony,” Aphrodite was born near the island of Cythera from the seed and blood of Uranus castrated by Kronos, which fell into the sea and formed snow-white foam (hence the nickname “foam-born”). The breeze brought her to the island of Cyprus (or she sailed there herself, since she did not like Cythera), where she, emerging from the sea waves, was met by the Ora.

The statue of Aphrodite (Venus of Tauride) dates back to the 3rd century BC. e., now it is in the Hermitage and is considered his most famous statue. The sculpture became the first antique statue of a naked woman in Russia. Life-size marble statue of bathing Venus (height 167 cm), modeled after the Aphrodite of Cnidus or the Capitoline Venus. The hands of the statue and a fragment of the nose are lost. Before entering the State Hermitage, she decorated the garden of the Tauride Palace, hence the name. In the past, “Venus Tauride” was intended to decorate the park. However, the statue was delivered to Russia much earlier, even under Peter I and thanks to his efforts. The inscription made on the bronze ring of the pedestal recalls that Venus was given by Clement XI to Peter I (as a result of an exchange for the relics of St. Brigid sent to the Pope by Peter I). The statue was discovered in 1718 during excavations in Rome. Unknown sculptor of the 3rd century. BC. depicted the naked goddess of love and beauty Venus. A slender figure, rounded, smooth lines of the silhouette, softly modeled body shapes - everything speaks of a healthy and chaste perception of female beauty. Along with calm restraint (posture, facial expression), a generalized manner, alien to fractionality and fine detail, as well as a number of other features characteristic of the art of the classics (V - IV centuries BC), the creator of Venus embodied in her his idea of beauty, associated with the ideals of the 3rd century BC. e. (graceful proportions - high waist, somewhat elongated legs, thin neck, small head - tilt of the figure, rotation of the body and head).

Italy. Antique sculpture in the Vatican Museum.

Joseph Brodsky

Torso

If you suddenly wander into stone grass,

looking better in marble than in reality,

or you notice a faun indulged in fuss

with a nymph, and both are happier in bronze than in a dream,

you can release the staff from your weary hands:

you are in the Empire, friend.

Air, fire, water, fauns, naiads, lions,

taken from nature or from the head -

everything that God came up with and I'm tired of continuing

brain, turned into stone or metal.

This is the end of things, this is the end of the road

mirror to enter.

Stand in a vacant niche and, rolling your eyes,

watch the centuries pass, disappearing behind

corner, and how moss sprouts in the groin

and dust falls on the shoulders - this tan of eras.

Someone will break off their hand and their head will fall off their shoulder

rolls down, knocking.

And what remains is the torso, an anonymous sum of muscles.

After a thousand years, a mouse living in a niche with

with a broken claw, without overcoming granite,

going out one evening, squeaking, mincing

across the road so as not to end up in a hole

at midnight. Not in the morning.

10 secrets of famous sculptures

The silence of the great statues holds many secrets. When Auguste Rodin was asked how he created his statues, the sculptor repeated the words of the great Michelangelo: “I take a block of marble and cut off everything unnecessary from it.” This is probably why the sculpture of a true master always creates a feeling of miracle: it seems that only a genius can see the beauty that is hidden in a piece of stone.

We are sure that in almost every significant work of art there is a mystery, a “double bottom” or a secret story that you want to reveal. Today we will share a few of them.

1. Horned Moses

Michelangelo Buanarrotti, "Moses", 1513-1515

Michelangelo depicted Moses with horns in his sculpture. Many art historians attribute this to misinterpretation of the Bible. The Book of Exodus says that when Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the tablets, the Jews found it difficult to look at his face. At this point in the Bible, a word is used that can be translated from Hebrew as both “rays” and “horns.” However, from the context it can be clearly said that we are talking specifically about rays of light - that Moses’ face shone and was not horned.

2. Colored Antiquity

"Augustus from Prima Porta", antique statue.

It has long been believed that ancient Greek and Roman white marble sculptures were originally colorless. However, recent research by scientists has confirmed the hypothesis that the statues were painted in a wide range of colors, which eventually disappeared under prolonged exposure to light and air.

3. The Little Mermaid's suffering

Edward Eriksen, The Little Mermaid, 1913

The Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen is one of the most long-suffering in the world: it is the one that vandals love most. The history of its existence was very turbulent. It was broken and sawed into pieces many times. And now you can still detect barely noticeable “scars” on the neck, which appeared from the need to replace the sculpture’s head. The Little Mermaid was beheaded twice: in 1964 and 1998. In 1984, her right hand was sawed off. On March 8, 2006, a dildo was placed on the mermaid’s hand, and the unfortunate woman herself was splashed with green paint. In addition, on the back there was a scrawled inscription “Happy March 8!” In 2007, Copenhagen authorities announced that the statue might be moved further into the harbor to avoid further incidents of vandalism and to prevent tourists from continually attempting to climb it.

4. “Kiss” without a kiss

Auguste Rodin, "The Kiss", 1882

Auguste Rodin's famous sculpture "The Kiss" was originally called "Francesca da Rimini", in honor of the noble Italian lady of the 13th century depicted on it, whose name was immortalized by Dante's Divine Comedy (Second Circle, Fifth Canto). The lady fell in love with her husband Giovanni Malatesta's younger brother, Paolo. While they were reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere, they were discovered and then killed by her husband. In the sculpture you can see Paolo holding a book in his hand. But in fact, the lovers do not touch each other's lips, as if hinting that they were killed without committing a sin.

The renaming of the sculpture to a more abstract one - The Kiss (Le Baiser) - was made by critics who first saw it in 1887.

5. The secret of the marble veil

Raphael Monti, "Marble Veil", mid-19th century.

When you look at the statues covered with a translucent marble veil, you can’t help but think about how it’s even possible to make something like this out of stone. It's all about the special structure of the marble used for these sculptures. The block that was to become a sculpture had to have two layers - one more transparent, the other more dense. Such natural stones are difficult to find, but they exist. The master had a plot in his head, he knew exactly what kind of block he was looking for. He worked with it, respecting the texture of the normal surface, and walked along the boundary separating the denser and more transparent part of the stone. As a result, the remnants of this transparent part “shone through”, which gave the effect of a veil.

6. Ideal David made of spoiled marble

Michelangelo Buanarrotti, "David", 1501-1504

The famous statue of David was made by Michelangelo from a piece of white marble left over from another sculptor, Agostino di Duccio, who tried unsuccessfully to work with the piece and then abandoned it.

By the way, David, who has been considered a model of male beauty for centuries, is not so perfect. The fact is that he is cross-eyed. This conclusion was reached by American scientist Mark Livoy from Stanford University, who examined the statue using laser-computer technology. The “vision defect” of the more than five-meter sculpture is invisible, since it is placed on a high pedestal. According to experts, Michelangelo deliberately endowed his brainchild with this flaw, because he wanted David’s profile to look perfect from any side.

Death that inspired creativity

7. “Kiss of Death”, 1930

The most mysterious statue in the Catalan cemetery of Poblenou is called “Kiss of Death”. The sculptor who created it still remains unknown. Usually the authorship of “The Kiss” is attributed to Jaume Barba, but there are also those who are sure that the monument was sculpted by Joan Fonbernat. The sculpture is located in one of the far corners of the Poblenou cemetery. It was she who inspired film director Bergman to create the film “The Seventh Seal” - about the communication between the Knight and Death.

8. Hands of Venus de Milo

Agesander (?), "Venus de Milo", c. 130-100 BC

The figure of Venus takes pride of place in the Louvre in Paris. A Greek peasant found it in 1820 on the island of Milos. At the time of discovery, the figure was broken into two large fragments. In her left hand the goddess held an apple, and with her right hand she held the falling robe. Realizing the historical significance of this ancient sculpture, officers of the French navy ordered the marble statue to be removed from the island. As Venus was being dragged over the rocks to the waiting ship, a fight broke out between the porters and both arms were broken off. The tired sailors flatly refused to return and look for the remaining parts.

9. The beautiful imperfection of Nike of Samothrace

"Nike of Samothrace", II century. BC.

The statue of Nike was found on the island of Samothrace in 1863 by Charles Champoiseau, a French consul and archaeologist. A statue carved from golden Parian marble on the island crowned the altar of sea deities. Researchers believe that an unknown sculptor created Nike in the 2nd century BC as a sign of Greek naval victories. The hands and head of the goddess are irretrievably lost. Attempts were made repeatedly to restore the original position of the goddess’s hands. It is believed that the right hand, raised upward, held a cup, wreath or forge. Interestingly, multiple attempts to restore the hands of the statue were unsuccessful - they all spoiled the masterpiece. These failures force us to admit: Nika is beautiful just like that, perfect in her imperfection.

10. Mystical Bronze Horseman

Etienne Falconet, Monument to Peter I, 1768-1770

The Bronze Horseman is a monument surrounded by mystical and otherworldly stories. One of the legends associated with him says that during the Patriotic War of 1812, Alexander I ordered especially valuable works of art to be removed from the city, including a monument to Peter I. At this time, a certain Major Baturin achieved a meeting with the Tsar’s personal friend, Prince Golitsyn and told him that he, Baturin, was haunted by the same dream. He sees himself on Senate Square. Peter's face turns. The horseman rides off his cliff and heads through the streets of St. Petersburg to Kamenny Island, where Alexander I then lived. The horseman enters the courtyard of the Kamenoostrovsky Palace, from which the sovereign comes out to meet him. “Young man, what have you brought my Russia to,” Peter the Great tells him, “but as long as I’m in place, my city has nothing to fear!” Then the rider turns back, and the “heavy, ringing gallop” is heard again. Struck by Baturin’s story, Prince Golitsyn conveyed the dream to the sovereign. As a result, Alexander I reversed his decision to evacuate the monument. The monument remained in place.

*****

Greece and art are inseparable concepts. In numerous archaeological museums you can see ancient sculptures and bronze statues, many of which were raised from the bottom of the Aegean Sea. Local history museums display handicrafts and textiles, and the best museums in Athens rival art galleries elsewhere in Europe.

Athens, Archaeological Museum of Piraeus.

Origin: The statue was discovered among others in 1959 in Piraeus, at the intersection of Georgiou and Philon streets in a storage room near the ancient harbor. The sculpture was hidden in this room from Sulla's troops in 86 BC. e.

Description:Bronze statue of Artemis

This type of powerful female figure was originally identified as the poetess or muse of Silanion's sculptural compositions. This statue is identified as an image of Artemis by the presence of a quiver belt on the back, as well as by the arrangement of the fingers of the hand that held the bow. This work of classicizing style is attributed to Euphranor on the basis of its resemblance to Apollo Patros on the Agora.

ancient greek sculpture classic

Ancient Greek sculpture from the Classical period

Speaking about the art of ancient civilizations, first of all we remember and study the art of Ancient Greece, and in particular its sculpture. Truly, in this small beautiful country, this art form has risen to such a height that to this day it is considered a standard throughout the world. Studying the sculptures of Ancient Greece allows us to better understand the worldview of the Greeks, their philosophy, ideals and aspirations. In sculpture, as nowhere else, the attitude towards man, who in Ancient Greece was the measure of all things, is manifested. It is sculpture that gives us the opportunity to judge the religious, philosophical and aesthetic ideas of the ancient Greeks. All this allows us to better understand the reasons for the rise, development and fall of this civilization.

The development of Ancient Greek civilization is divided into several stages - eras. First, briefly, I will talk about the Archaic era, since it preceded the classical era and “set the tone” in sculpture.

The Archaic period is the beginning of the formation of ancient Greek sculpture. This era was also divided into early archaic (650 - 580 BC), high (580 - 530 BC), and late (530 - 480 BC). The sculpture was the embodiment of an ideal person. She exalted his beauty, his physical perfection. Early single sculptures are represented by two main types: the image of a naked young man - kouros and the figure of a girl dressed in a long, tight-fitting chiton - kora.

The sculpture of this era was very similar to the Egyptian ones. And this is not surprising: the Greeks, getting acquainted with Egyptian culture and the cultures of other countries of the Ancient East, borrowed a lot, and in other cases discovered similarities with them. Certain canons were observed in the sculpture, so they were very geometric and static: a person takes a step forward, his shoulders are straightened, and his arms are lowered along the body, a stupid smile always plays on his lips. In addition, the sculptures were painted: golden hair, blue eyes, pink cheeks.

At the beginning of the classical era, these canons are still in effect, but later the author begins to move away from statics, the sculpture acquires character, and an event, an action, often occurs.

Classical sculpture is the second era in the development of ancient Greek culture. It is also divided into stages: early classic or strict style (490 - 450 BC), high (450 - 420 BC), rich style (420 - 390 BC .), Late Classic (390 - ca. 320 BC).

In the era of the early classics, a certain life rethinking takes place. The sculpture takes on a heroic character. Art is freeing itself from the rigid framework that shackled it in the archaic era; this is a time of searching for new, intensive development of various schools and directions, and the creation of diverse works. The two types of figures - kurosu and kore - are being replaced by a much greater variety of types; the sculptures strive to convey the complex movement of the human body.

All this takes place against the backdrop of the war with the Persians, and it was this war that so changed ancient Greek thinking. The cultural centers were shifted and are now the cities of Athens, the Northern Peloponnese and the Greek West. By that time, Greece had reached the highest point of economic, political and cultural growth. Athens took a leading place in the union of Greek cities. Greek society was democratic, built on the principles of equal activity. All men inhabiting Athens, except slaves, were equal citizens. And they all enjoyed the right to vote and could be elected to any public office. The Greeks were in harmony with nature and did not suppress their natural desires. Everything that was done by the Greeks was the property of the people. Statues stood in temples and squares, on palaestras and on the seashore. They were present on the pediments and in the decorations of temples. As in the archaic era, the sculptures were painted.

Unfortunately, Greek sculpture has come down to us mainly in rubble. Although, according to Plutarch, there were more statues in Athens than living people. Many statues have come down to us in Roman copies. But they are quite crude compared to the Greek originals.

One of the most famous sculptors of the early classics is Pythagoras of Rhegium. Few of his works have reached us, and his works are known only from mentions of ancient authors. Pythagoras became famous for his realistic depiction of human veins, veins and hair. Several Roman copies of his sculptures have survived: “Boy Taking out a Splinter”, “Hyacinth”, etc. In addition, he is credited with the famous bronze statue “Charioteer”, found in Delphi. Pythagoras of Rhegium created several bronze statues of the winning athletes of the Olympic and Delphic Games. And he owns the statues of Apollo - the Python Slayer, the Rape of Europa, Eteocles, Polyneices and the Wounded Philoctetes.

It is known that Pythagoras of Rhegium was a contemporary and rival of Myron. This is another famous sculptor of that time. And he became famous as the greatest realist and expert in anatomy. But despite all this, Myron did not know how to give life and expression to the faces of his works. Myron created statues of athletes - winners of competitions, reproduced famous heroes, gods and animals, and especially brilliantly depicted difficult poses that looked very realistic.

The best example of such a sculpture of his is the world-famous “Discobolus”. Ancient writers also mention the famous sculpture of Marsyas and Athena. This famous sculptural group has come down to us in several copies. In addition to people, Myron also depicted animals, his image of “Cows” is especially famous.

Myron worked mainly in bronze; his works have not survived and are known from the testimonies of ancient authors and Roman copies. He was also a master of toreutics - he made metal cups with relief images.

Another famous sculptor of this period is Kalamis. He created marble, bronze and chryselephantine statues, and depicted mainly gods, female heroic figures and horses. The art of Kalamis can be judged by the copy that has come down to us from a later time of a statue of Hermes carrying a ram that he made for Tanagra. The figure of the god himself is executed in an archaic style, with the immobility of the pose and the symmetry of the arrangement of the limbs characteristic of this style; but the ram carried by Hermes is already distinguished by some vitality.

In addition, the pediments and metopes of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia are among the monuments of ancient Greek sculpture of the early classics. Another significant work of early classics is the so-called “Throne of Ludovisi”. This is a three-sided marble altar depicting the birth of Aphrodite, on the sides of the altar are hetaeras and brides, symbolizing different hypostases of love or images of serving the goddess.

High classics are represented by the names of Phidias and Polykleitos. Its short-term heyday is associated with work on the Athenian Acropolis, that is, with the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon. The pinnacle of ancient Greek sculpture was, apparently, the statues of Athena Parthenos and Olympian Zeus by Phidias.

Phidias is one of the best representatives of the classical style, and about his significance it is enough to say that he is considered the founder of European art. The Attic school of sculpture, headed by him, occupied a leading place in the art of high classics.

Phidias had knowledge of the achievements of optics. A story has been preserved about his rivalry with Alcamenes: both were ordered statues of Athena, which were supposed to be erected on high columns. Phidias made his statue in accordance with the height of the column - on the ground it seemed ugly and disproportionate. The neck of the goddess was very long. When both statues were erected on high pedestals, Phidias’s correctness became obvious. They note the enormous skill of Phidias in the interpretation of clothing, in which he surpasses both Myron and Polycletus.

Most of his works have not survived; we can only judge them from descriptions of ancient authors and copies. Nevertheless, his fame was colossal. And there were so many of them that what was left was already a lot. The most famous works of Phidias - Zeus and Athena Parthenos were made in the chrysoelephantine technique - gold and ivory.

The height of the statue of Zeus, together with the pedestal, was, according to various sources, from 12 to 17 meters. Zeus's eyes were the size of an adult's fist. The cape that covered part of Zeus's body, the scepter with an eagle in the left hand, the statue of the goddess Nike in the right and the wreath on his head are made of gold. Zeus sits on a throne; four dancing Nikes are depicted on the legs of the throne. Also depicted were: centaurs, lapiths, the exploits of Theseus and Hercules, frescoes depicting the battle of the Greeks with the Amazons.

The Athena Parthenon was, like the statue of Zeus, huge and made in the chrysoelephantine technique. Only the goddess, unlike her father, did not sit on the throne, but stood at full height. “Athena herself is made of ivory and gold... The statue depicts her in full height in a tunic down to the very soles of her feet, on her chest is the head of Medusa made of ivory, in her hand she holds an image of Nike, approximately four cubits, and in the other hand - - a spear. At her feet lies a shield, and near her spear is a serpent; this snake is probably Erichthonius.” (Description of Hellas, XXIV, 7).

The goddess's helmet had three crests: the middle one with a sphinx, the side ones with griffins. As Pliny the Elder writes, on the outside of the shield there was a battle with the Amazons, on the inside there was a fight between gods and giants, and on Athena’s sandals there was an image of a centauromachy. The base was decorated with a Pandora story. The goddess's tunic, shield, sandals, helmet and jewelry are all made of gold.

On marble copies, the hand of the goddess with Nike is supported by a pillar; whether it existed in the original is the subject of much debate. Nika seems tiny, in reality her height was 2 meters.

Athena Promachos is a colossal image of the goddess Athena brandishing a spear on the Athenian Acropolis. Erected in memory of victories over the Persians. Its height reached 18.5 meters and towered above all the surrounding buildings, shining over the city from afar. Unfortunately, this bronze goddess did not survive to this day. And we know about it only from chronicle sources.

Athena Lemnia - a bronze statue of the goddess Athena, created by Phidias, is also known to us from copies. This is a bronze statue depicting a goddess leaning on a spear. It was named after the island of Lemnos, for whose inhabitants it was made.

The Wounded Amazon, a statue that took second place in the famous sculpting competition for the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus. In addition to the above sculptures, others are also attributed to Phidias, based on stylistic similarity: a statue of Demeter, a statue of Kore, a relief from Eleusis, Anadumen (a young man tying a bandage around his head), Hermes Ludovisi, Tiberian Apollo, Kassel Apollo.

Despite Phidias' talent, or rather divine gift, his relationship with the inhabitants of Athens was not at all warm. As Plutarch writes in his Life of Pericles, Phidias was the main adviser and assistant to Pericles (an Athenian politician, famous orator and commander).

“Since he was a friend of Pericles and enjoyed great authority with him, he had many personal enemies and envious people. They persuaded one of Phidias' assistants, Menon, to denounce Phidias and accuse him of theft. Phidias was burdened with envy of the glory of his works... When his case was examined in the People's Assembly, there was no evidence of theft. But Phidias was sent to prison and died there of illness.”

Polykleitos the Elder is an ancient Greek sculptor and art theorist, a contemporary of Phidias. Unlike Phidias, it was not so large-scale. However, his sculpture has a certain character: Polykleitos loved to depict athletes in a state of rest, and specialized in depicting athletes, Olympic winners. He was the first to think of posing the figures in such a way that they rested on the lower part of only one leg. Polykleitos knew how to show the human body in a state of balance - his human figure at rest or at a slow pace seems mobile and animated. An example of this is the famous statue of Polykleitos “Doriphoros” (spearman). It is in this work that Polykleitos’s ideas about the ideal proportions of the human body, which are in numerical proportion to each other, are embodied. It was believed that the figure was created on the basis of the provisions of Pythagoreanism, therefore in ancient times the statue of Doryphorus was often called the “canon of Polykleitos.” The forms of this statue are repeated in most of the works of the sculptor and his school. The distance from the chin to the crown of the head in the statues of Polykleitos is one-seventh, while the distance from the eyes to the chin is one-sixteenth, and the height of the face is one-tenth of the entire figure. Polykleitos is firmly connected with the Pythagorean tradition. “The Canon of Polykleitos” is a theoretical treatise by the sculptor, created by Polykleitos so that other artists could use it. Indeed, the Canon of Polykleitos had a great influence on European culture, despite the fact that only two fragments of the theoretical work have survived, information about it is fragmentary, and the mathematical basis has not yet been finally deduced.

In addition to the spearman, other works of the sculptor are known: “Diadumen” (“Young Man Tying a Bandage”), “Wounded Amazon”, a colossal statue of Hera in Argos. It was made in the chrysoelephantine technique and was perceived as a pandan to Phidias the Olympian Zeus, “Discophoros” (“Young Man Holding a Disk”). Unfortunately, these sculptures have survived only in ancient Roman copies.

At the “Rich Style” stage, we know the names of such sculptors as Alkamen, Agorakrit, Callimachus, etc.

Alkamenes, Greek sculptor, student, rival and successor of Phidias. Alkamenes was considered to be the equal of Phidias, and after the latter's death, he became the leading sculptor in Athens. His Hermes in the form of a herm (a pillar crowned with the head of Hermes) is known in many copies. Nearby, near the temple of Athena Nike, there was a statue of Hecate, which represented three figures connected by their backs. On the Acropolis of Athens, a group belonging to Alkamen was also found - Procne, raising a knife over her son Itis, who was seeking salvation in the folds of her clothes. In the sanctuary on the slope of the Acropolis there was a statue of a seated Dionysus belonging to Alkamen. Alkamen also created a statue of Ares for the temple on the agora and a statue of Hephaestus for the temple of Hephaestus and Athena.

Alkamenes defeated Agoracritus in a competition to create a statue of Aphrodite. However, even more famous is the seated "Aphrodite in the Gardens", at the northern foot of the Acropolis. She is depicted on many red-figure Attic vases surrounded by Eros, Peyto and other embodiments of the happiness that love brings. The head often repeated by ancient copyists, called "Sappho", was possibly copied from this statue. Alkamen's last work is a colossal relief with Hercules and Athena. Alkamenes probably died soon after this.

Agorakritos was also a student of Phidias, and, as they say, his favorite. He, like Alkamen, participated in the creation of the Parthenon frieze. The two most famous works of Agorakritos are the cult statue of the goddess Nemesis (remade by Athena after the duel with Alcamenes), donated to the Temple of Ramnos, and the statue of the Mother of the Gods in Athens (sometimes attributed to Pheidias). Of the works mentioned by ancient authors, only the statues of Zeus-Hades and Athena in Coronea undoubtedly belonged to Agorakritos. Of his works, only part of the head of the colossal statue of Nemesis and fragments of the reliefs that decorated the base of this statue have survived. According to Pausanias, the base depicted young Helen (daughter of Nemesis), with Leda who nursed her, her husband Menelaus and other relatives of Helen and Menelaus.

The general character of late classical sculpture was determined by the development of realistic tendencies.

Scopas is one of the largest sculptors of this period. Skopas, preserving the traditions of monumental art of high classics, saturates his works with drama; he reveals the complex feelings and experiences of a person. The heroes of Skopas continue to embody the perfect qualities of strong and valiant people. However, Skopas introduces themes of suffering and internal breakdown into the art of sculpture. These are the images of wounded warriors from the pediments of the Temple of Athena Aley in Tegea. Plasticity, a sharp, restless play of chiaroscuro emphasizes the drama of what is happening.

Skopas preferred to work in marble, almost abandoning the material favored by the masters of high classics - bronze. Marble made it possible to convey a subtle play of light and shadow, and various textural contrasts. His Maenad (Bacchae), which survives in a small, damaged antique copy, embodies the image of a man possessed by a violent impulse of passion. The dance of the Maenad is swift, the head is thrown back, the hair falls in a heavy wave onto the shoulders. The movement of the curved folds of her chiton emphasizes the rapid impulse of the body.

The images of Skopas are either deeply thoughtful, like the young man from the tombstone of the Ilissa River, or lively and passionate.

The frieze of the Halicarnassus Mausoleum depicting the battle between the Greeks and the Amazons has been preserved in the original.

The impact of Skopas's art on the further development of Greek plastic arts was enormous, and can only be compared with the impact of the art of his contemporary, Praxiteles.

In his work, Praxiteles turns to images imbued with the spirit of clear and pure harmony, calm thoughtfulness, and serene contemplation. Praxiteles and Scopas complement each other, revealing the various states and feelings of a person, his inner world.

Depicting harmoniously developed, beautiful heroes, Praxiteles also reveals connections with the art of high classics, however, his images lose the heroism and monumental grandeur of the works of the heyday, but acquire a more lyrically refined and contemplative character.

Praxiteles’ mastery is most fully revealed in the marble group “Hermes with Dionysus”. The graceful curve of the figure, the relaxed resting pose of the young slender body, the beautiful, spiritual face of Hermes are conveyed with great skill.

Praxiteles created a new ideal of female beauty, embodying it in the image of Aphrodite, who is depicted at the moment when, having taken off her clothes, she is about to enter the water. Although the sculpture was intended for cult purposes, the image of the beautiful naked goddess was freed from solemn majesty. "Aphrodite of Cnidus" caused many repetitions in subsequent times, but none of them could compare with the original.

The sculpture of “Apollo Saurocton” is an image of a graceful teenage boy aiming at a lizard running along a tree trunk. Praxiteles rethinks mythological images; features of everyday life and elements of the genre appear in them.

If in the art of Scopas and Praxiteles there are still tangible connections with the principles of high classical art, then in the artistic culture of the last third of the 4th century. BC e., these ties are increasingly weakened.

Macedonia acquired great importance in the socio-political life of the ancient world. Just as the war with the Persians changed and rethought the culture of Greece at the beginning of the 5th century. BC e. After the victorious campaigns of Alexander the Great and his conquest of the Greek city-states, and then the vast territories of Asia that became part of the Macedonian state, a new stage in the development of ancient society began - the period of Hellenism. The transitional period from the late classics to the Hellenistic period proper is distinguished by its peculiar features.

Lysippos is the last great master of the late classics. His work unfolds in the 40-30s. V century BC e., during the reign of Alexander the Great. In the art of Lysippos, as well as in the work of his great predecessors, the task of revealing human experiences was solved. He began to introduce more clearly expressed features of age and occupation. What is new in Lysippos’s work is his interest in the characteristically expressive in man, as well as the expansion of the visual possibilities of sculpture.

Lysippos embodied his understanding of the image of man in the sculpture of a young man scraping sand off himself after a competition - “Apoxiomenes”, whom he depicts not in a moment of exertion, but in a state of fatigue. The slender figure of the athlete is shown in a complex turn, which forces the viewer to walk around the sculpture. The movement is freely deployed in space. The face expresses fatigue, the deep-set, shadowed eyes look into the distance.

Lysippos skillfully conveys the transition from a state of rest to action and vice versa. This is the image of Hermes resting.

The work of Lysippos was of great importance for the development of portraiture. The portraits he created of Alexander the Great reveal a deep interest in revealing the spiritual world of the hero. Most notable is the marble head of Alexander, which conveys his complex, contradictory nature.

The art of Lysippos occupies the border zone at the turn of the classical and Hellenistic eras. It is still true to classical concepts, but it is already undermining them from the inside, creating the basis for a transition to something else, more relaxed and more prosaic. In this sense, the head of a fist fighter is indicative, belonging not to Lysippos, but, possibly, to his brother Lysistratus, who was also a sculptor and, as they said, was the first to use masks taken from the model’s face for portraits (which was widespread in Ancient Egypt, but completely alien to Greek art). It is possible that the head of a fist fighter was also made using the mask; it is far from the canon, far from the ideal ideas of physical perfection that the Hellenes embodied in the image of an athlete. This winner in a fist fight is not at all like a demigod, just an entertainer for an idle crowd. His face is rough, his nose is flattened, his ears are swollen. This type of “naturalistic” images subsequently became common in Hellenism; an even more unsightly fist fighter was sculpted by the Attic sculptor Apollonius already in the 1st century BC. e.

What had previously cast shadows on the bright structure of the Hellenic worldview came at the end of the 4th century BC. e.: decomposition and death of the democratic polis. This began with the rise of Macedonia, the northern region of Greece, and the virtual seizure of all Greek states by the Macedonian king Philip II.

Alexander the Great tasted the fruits of the highest Greek culture in his youth. His teacher was the great philosopher Aristotle, and his court artists were Lysippos and Apelles. This did not prevent him, having captured the Persian state and taken the throne of the Egyptian pharaohs, from declaring himself a god and demanding that he be given divine honors in Greece as well. Unaccustomed to eastern customs, the Greeks chuckled and said: “Well, if Alexander wants to be a god, let him be” - and officially recognized him as the son of Zeus. However, Greek democracy, on which its culture grew, died under Alexander and was not revived after his death. The newly emerged state was no longer Greek, but Greek-Eastern. The era of Hellenism has arrived - the unification under the auspices of the monarchy of Hellenic and Eastern cultures.