The role of the writer as the creator of a literary work. In a literary work

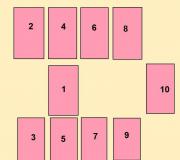

Rental block

The word “author” is used in literary studies in several meanings. First of all, it means a real person. In other cases, it denotes a certain view of reality, the expression of which is the entire work (the image of the author). Finally, this word is used to refer to some. phenomena characteristic of certain genres and types (the author is the narrator, narrator (in epic works) or lyrical hero (in lyric poetry))” (B.O. Korman). Biogr. the author can choose one of three forms of narration FROM THE AUTHOR (objective form of narration, from the 3rd person): apparent absence in the work. any subject of the story. ON BEHALF OF THE NARRATOR, BUT NOT THE HERO. The narrator manifests himself in emotional statements about the characters, their actions, relationships, and experiences. “Belkin's Tales” by Pushkin IN THE PERSON OF THE HERO. The author conveys the narration to the hero when he wants to reveal his hero more deeply or in the case of depicting a positive hero. Example: “The Captain's Daughter” by Pushkin, where the narration is told on behalf of Grinev. Forms of the author’s presence in the work (lyrical digressions) Direct expression by the author of the epic work of his thoughts and feelings are revealed in lyrical digressions. Remarks - author's comments about the behavior or character of characters. HERO - the main or one of the main characters in a prose or dramatic work; G.l. may be "major" or "minor". The hero’s external appearance is created by his portrait, profession, age, history (or past), and name. Famous literary characters live a completely independent life independent of their creators, not only in literary texts. Methods and forms of author's presence in literary work: The forms of authorial presence depend on the type of literature. -Epic is a story. On grammatical basis There are 3 forms of narration: - from the 1st person - from the 3rd person - improperly direct speech - the speech of the hero, not enclosed in quotation marks. Such speech is formally a narrative, but in content it is similar to the character’s speech. 1st person narration is a personal narration, 3rd person narration is impersonal. Very often, in a personal narration, the narrator is personified; in an impersonal narration, the narrator is non-personalized or the narrator. -Drama - there are no forms of the author’s presence, there are only his “traces”, because form of verbal expression in drama - dialogue or polylogue - there is no author, there are only heroes. The clearest presence of the author is in the lyrics. Korman's classification: 1. The author himself is close to the narrator in the epic, this is manifested in those works where the subject of the image is objects of the world. The world in the lyrics is always psychologized (the inner world of the hero is expanded). The degree of secrecy of the author in the text: -3rd person -1st person (plural). “We” is a generalized carrier of consciousness. In such texts the form is observation or reflection. 2. Author-narrator - manifests itself in those texts that talk about the fate of a person. In the modern classification, these 2 forms are combined and speak of a lyrical narrator. 3. The lyrical hero is the subject of speech through whom the biographical and emotional-psychological traits of the author are expressed. The lyrical hero is a monologue form of the author's expression in the text. 4. Role hero - the indirect expression of the author in the text through the sociocultural type of the past or present. Role-playing hero is a dialogical form. 5. Poetic world - the author’s subjectivity is expressed in the world or in what is depicted. 6. Interpersonal subject - the form realizes different points of view on the world.

We have the largest information database in RuNet, so you can always find similar queries

This topic belongs to the section:

Literature. Answers

What is literature? How was literary theory born and how did it grow? Verse and prose. the nature of the verse. Syllabic-tonic system of versification What is an epic novel? Types of Comedy

This material includes sections:

Literature in the understanding of the Russian formal school. Defamiliarization. Automation/de-automation. Naked reception

Literature in the understanding of structuralism: what's new?

Poststructuralism is a general name for a number of approaches in social, humanitarian and philosophical knowledge

Image. Can literature exist without images?

Imitation, stylization, parody

Basic systems of versification

Meter and rhythm in verse

Strophic. Main types of stanzas

The birth of rhythym, its flourishing and degradation

Sound recording in verse. Melodica

Repetition in literature. Repetition in verse is not at all the same as in prose

Literary genres: epic, lyric, drama

Heroic, sublime, comic

Varieties of comic. Humor and satire

Main epic genres

Main lyrical genres

Basic dramatic genres. What is a dramatic text?

Short story and short story: what's the difference?

Types of novel

What is composition? What does it include?

Types of tragedy

How does the drama genre differ from the tragedy genre?

The plot and its composition. How does a plot differ from a plot?

What does the character consist of?

Author and text. Forms of the author's presence in the work

Who tells the story. Forms of storytelling. Author, narrator, hero

What is skaz?

How does literature develop and how can its development be described? Theory of artistic methods/literary movements and other concepts of literary evolution

What is classicism?

What is romanticism?

Introduction to the course "Corporate Governance"

Course of lectures on the discipline “Corporate Governance”. Introduction to the course. The concept of corporate governance. The difference between corporate governance and corporate management. Genesis of corporate governance (in Russia and abroad). Corporate governance system, principles and factors of its construction

Administrative offenses in the field of business activities

general characteristics rosters and qualifications individual species administrative offenses in the field entrepreneurial activity and activities of self-regulatory organizations, finance, taxes and fees, insurance, securities market, customs

Final state exam “Pedagogy and Psychology”

The state educational standard for the specialty of higher professional education “Pedagogy and Psychology” was approved by order of the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation No. 686 in 2005. Graduate qualification: educational psychologist.

© 2013 M.S. Yankelevich

St. Petersburg State University

The article was received by the editor on January 22, 2013

This article discusses various theoretical approaches to the problem of reflecting the psychological characteristics of the author in a work of art and some psychological aspects formation of the image of the author through contact with the work created by him.

Art has enormous formative potential in relation to the value sphere of the individual. The perception of objects of artistic culture actualizes the moral and aesthetic values of the individual. Ideas reflected in figurative artistic form, resonate in individual consciousness. Artistic culture plays the role of a catalyst of personal meaning for the perceiver. This impact, unique in its power, is mediated by the personality of the author.

3. Freud, K. Jung, M. M. Bakhtin, M. S. Kogan,

4. Lombroso, U. Eco and many others. An important theoretical idea, called the “Henneken hypothesis,” is that the works of authors who are close to us in their psychological characteristics are rated higher by us than the works of those authors whose psychological characteristics radically opposite to our own. This idea was considered by E. Hennequin in his work “La critique scientifique” published in France in 1888 (“The experience of constructing scientific criticism"-1892)1. Although the hypothesis was not empirically tested either by the scientist himself or by his followers, it was later developed in theoretical studies by such scientists as N.A. Rubakin (1977), M.E. Burno (1989), V. P. Belyanin (2006) and others.

Another important theoretical aspect of studying the reflection of the author’s personality in a work of artistic culture is associated with the consideration of the work as a method

Yankelevich Marina Sergeevna, graduate student of the Department of General Psychology, psychologist. E-mail: radaveselova&list. ru

1 Genneken E. Experience in constructing scientific criticism. -

translations of meanings. The following scientists worked in this direction: M.M. Bakhtin, A.N. Leontiev, A.A. Leontiev, D.A. Leontiev. Process of perception work of art is a process of mediated communication. In the process of perceiving, for example, a film, the viewer makes recognition visual information for further processing of semantic information and subsequent reaction to it. In essence, we are talking about solving a communicative problem - guessing the creator’s thought and evaluating it. In the process of watching a film, the viewer perceives semantically the information contained in the literary text. We can talk about the implementation of the process of indirect communication, interaction with the author of a work of artistic culture. The perception of a work of art is an active interaction between the communicator and the recipient. G.M. Andreeva characterized the communication process through 3 components: communicative, interactive and perceptual2. First of all, let us focus on the fact that the process of perceiving a work of art can be considered exclusively as indirect communication with the author. Thus, the interactivity characteristic does not apply to it. The remaining two characteristics of the communication process are relevant for the case we are considering. The communicative side involves the exchange of information between participants in communication, the perceptual side includes the perception and knowledge of each other.

It is necessary to distinguish between the author as a real historical figure and the author as an active subject of artistic communication. Since a work of art cannot reflect the personality of the author in its entirety, we are interested in the author as a novelist.

2 Andreeva G.M. Psychology of social cognition. -M.: 1997.

the bearer of the ideological concept of a work of art.

A work of art is a special case of a subjective reflection of objective reality. Thinking is the process of reflecting the objective world in a subjective way. In artistic thinking, the indirect nature of reflection is most obvious. The very value of artistic reflection is associated with the uniqueness of the creator’s personality. The choice of object on which the author focuses his attention is already born from a subjective personal view of the world. Any work of art is a unity of reflected reality and an individual attitude towards it, expressed in figurative form.

In artistic narrative works, the plot is one of the forms of expression of the author's concept of reality, the implementation of personal ideas about the dynamics of life processes. The author's concept of being is expressed in the nature of the combination of an event-related plot series and an intrapersonal plot series. The concept of the author can also be characterized through linguistic units that are the dominant elements of the plot and composition, which, as a rule, occupy “strong” positions in the narrative: epigraph, beginning, end, reference points compositions. In an artistic narrative, the author's position can also be manifested through the so-called author's digressions, such as epigraphs and afterwords.

Art, unlike other types of social consciousness, operates not with concepts, but with images, which in their concrete individuality carry a certain generalization. An image is more visual than a concept. He is characterized by great persuasiveness. The basis of artistry is imagery. It is thanks to their imagery that works of art acquire aesthetic value. With the help of artistic images, the author expresses his assessment of life phenomena. A work of art seeks to establish a certain value system in the minds of the perceiver. The author sets moral, cultural and aesthetic levels, influencing the formation of the personality of those who turn to his works.

Traditionally, science discusses the function of self-expression in creative activity. It should be noted that we can talk not only about the self-expression of the author, but also the self-expression of the perceiver. Not only the personality of the author can find expression in the work. By perceiving a work that resonates with our personality, we can

are able to identify themselves with the author and, referring to him, express their own position. People traditionally illustrate their state or position in relation to various objects of reality, referring to paintings, films, photographs, lines. This happens as a result of indirect communication with the author.

In the 30s of the 20th century, V.V. Vinogradov concentrated his attention on developing the concept of “image of the author” in fiction. Constructing the image of the author based on the perception of a work of art is a bidirectional process built on communication between two parties. On the one hand, the image of the author in a work is created on the basis of the structure of an object created by a specific person, on the other hand, it can only be created by the one who turned to this work, since it is in the field of perception. The image of the author is the central concept of the theory of artistic speech by V.V. Vinogradov, who considered it primarily in linguistic expression. Vinogradov defined the image of the author as follows: “An individual verbal and speech structure that permeates the structure of a work of art and determines the relationship and interaction of its elements. The general principle of the style of a literary work. This verbal and speech structure is reflected in the alternation of different functional speech types, in the change of different forms of speech, which together create a holistic and internally unified image of the author”3.

V.B. Kitaev noted that it would be incorrect to see the possibility of only a linguistic description of the image of the author of a literary text. In his opinion, the human essence of the author is reflected in elements that, being expressed through language, are not linguistic. Vinogradov believed that the image of the author should be sought in the principles and laws of verbal and artistic construction, however, the image of the author, his message is more intuitively guessed than built on the basis of materially represented signs. Vinogradov defined the “image of the author” as the expression of the artist’s personality in his creation. “The image of the author is the center, the focus, in which all the stylistic devices of works of art are crossed and combined, synthesized”4.

The image of the author is a concentrated embodiment of the essence of the work, or the moral attitude of the author to the subject, embodied in the structure of the work of art. The author’s personality finds its manifestation in art

4 Ibid. - P. 215.

natural texts through the way speech is organized, regardless of whether it is used consciously. The image of the author is always a product of co-creation by the one who perceives the work of art and its creator. Since the consciousness of the perceiver is always individual, it is possible for different people to construct significantly different images of the author. The image of the author, in essence, is an individual perception of his personality, reflected in the work.

B.O. Korman presents a systematic approach to the problem of authorship. Corman understands the author as a subject - a “carrier of consciousness”, the expression of which is the entire work or set of works5. The author, in Corman's understanding, is separated from the author as a real person. B.O. Korman introduced the concept of “subjective organization” - a system of subject-object relations through which the author is mediated, the subject is the one whose consciousness is expressed in the text, the object is what the subject’s consciousness is directed towards. The one whose consciousness is expressed in the text is the subject of consciousness, the one on whose behalf speech is conducted is the subject of speech. The formal-subjective organization correlates with the subjects of speech, and the content-subjective organization correlates with the subjects of consciousness. Corman understood the author's consciousness as the unity of the narrator's consciousness and the narrator's consciousness.

According to M.M. Bakhtin, in the process of creating a work, the author constructs an “artistic model of the world”, where the consciousness of the author is always external to the consciousness of the hero6. In the process of perceiving a work, a person, on the one hand, must consider the author’s model of the world, and on the other, evaluate it and compare it with his own. M.M. Bakhtin interprets this interaction as “co-creation of those who understand” - a specific dialogue mediated by a literary text. The scientists who developed his ideas talk about the possibility of treating the world as a whole as a text to be deciphered. This point of view is illuminated in the works of such scientists as N.A. Rubakin, M.N. Kufaev, S.M. Borodin, V.A. Borodin, V.A. Dmitriev, I.N. Tarakanova and others. M.M. Bakhtin identified three components within the concept of “author”. Bakhtin's triad was built as follows: “biographical author - primary author - secondary author.” The primary author is a real historical figure, endowed with a biography and located outside the work.

5 Korman B. O. Studying the text of a work of art. Tutorial. - M.: 1972. - P. 4.

6 Korman B.O. From observations on the terminology of M.M. Bakhtin. - In the book: The problem of the author in Russian literature of the 19th - 20th centuries. - Izhevsk: 1978. - S. 188 - 189.

The secondary author is the subject of creative activity. The author as a subject of aesthetic activity, a creative force, is what M.M. Bakhtin calls the primary author. Its main criterion is the principle of “out-of-location”. The artist should not interfere with the event as a direct participant in it, he should only contemplate. The secondary author, revealing himself in the structure and meaning of a literary text, operates with a word, which is represented by the author’s method of narration. For M.M. Bakhtin, the word is not a neutral object of linguistics, but an ideologically and expressively marked unit. E.Yu. Geim-bukh considered the image of the author as an algorithm for perceiving the subjective sphere of a literary work, that is, the relationship between the speech parts of the characters, the narrator and the narrator.

N.L. Myshkina focused her attention on emphasizing spiritual world author. The formation of the author’s image occurs due to the “flickering” meanings or emanations of a work of art, affecting the recipient’s subconscious. “In a literary text one finds an explicit or implicit expression of the consciousness of a real author (arteator), a mentor and a multitude of subjects (“inductors”) - exponents of ideas with which it confronts or consolidates through

7 Rubakin N.A. Psychology of the reader and the book. - M.: 1977. - P. 59 - 60.

8 Kufaev M.N. The book is in the process of communication. - M.: 1927. - P. 38.

menteavtora arteavtor”9. N.L. Myshkina reveals the problem of authorship through the concept of a pragmamodule, which is revealed in three aspects: 1) the author’s attitude to the world - a worldview position expressed in the author’s position of the picture of the world, acting as a unity of artistic, scientific, social, business and everyday aspects; 2) its relationship to the addressee - address position, considered as a hidden category associated with the analysis of pragmatic categories of the text; 3) his attitude towards language, including linguistic competence - language position10.

Without a doubt, artistic perception is a complex communicative process in which the recipient and the author take part. The author's primary task is always to construct an artistic model that can accurately reflect his ideas about the world. The receiving party attempts to decode and evaluate this message, and then it becomes possible for it to formulate its idea of the author’s personality, his value guidelines, etc.

We have come to an understanding of a work of art as a way of transmitting meanings. In his article “Some problems of the psychology of art,” A. N. Leontyev talks about three functions of art: emotional, informational and the mechanism for transmitting meanings, where he calls the last one the main, specific one11. Developing this idea in her works on the psychology of art, D. A. Leontyeva uses the concept of “disposition”, interpreted as an attitude towards phenomena and objects of reality that have a stable life meaning, which exists in the form of a fixed attitude and manifests itself in the effects of personal-semantic and attitudinal-semantic regulation, not related to the motive of actual activity12. When applied to objects of artistic culture, we can talk about the artistic disposition of the perceiver. An artistic image (quasi-object of art), according to A.N. Leontyev, is a real object that the author describes and endows the image with the characteristics of that object. And to perceive it, it is enough to perceive those signs of this image that can relate to the subject or how broad

9 Myshkina N.L. Dynamic-systemic study of the meaning of the text. - Krasnoyarsk: 1991. - P. 41, 100.

10 Ibid. - P. 41, 100.

11 Leontyev A. N. Selected psychological works. - M.: 1983. - P. 233.

12 A work of art and personality: psychological

skaya structure of interaction // Artistic creativity and psychology / Ed. A.Ya.Zisya,

M.G. Yaroshevsky. - M.: 1991.

class of objects, but are certainly carriers and translators of personal meanings13.

Leontyev identified two main interpretations of a work of artistic culture: 1) A work of art as a reflection of reality, refracted through the personality of the author. In this case, the paradox of artistic perception lies in the fact that only by refusing to perceive the work through the prism of one’s own meanings, it becomes possible to enrich one’s own meanings with those inherent in the work by the author, embodied both in the elements of the artistic text and in the patterns of its structural organization. 2) A work of art as a reflection of the author’s personality, projected onto the content of the work14.

So, we examined one of the aspects of the perception of a work of art - communicative. The second aspect is the perceptual aspect. Social perception - the perception of people by each other - forms the basis of communication and influences its communicative aspect. The result of social perception is the construction of an image of a partner. The term social perception was introduced by J. Bruner in 1947. This term in the narrow sense refers to the social determination of perceptual processes. In broad terms, it is the process of perceiving social objects, in which the perception of a person by a person does not exhaust the very area of social perception. The success of communication and the satisfaction of the parties largely depends on the ability to construct an image of a partner adequate to reality. The perceptual side of communication through the perception of a work of art consists in constructing an image of the author, read from the work itself.

In the scientific literature, analysis of works of art in connection with the individual psychological characteristics of the authors can be found in the works of psychologists - representatives of various schools. Thus, Z. Freud wrote about sublimation as the main mechanism of artistic creativity. According to Freud, the engine of artistic activity is a person’s desire to express his asocial fantasies and drives in a form acceptable to society. Freud believed that creative activity reconciles two divergent principles: the “principle of reality” and the “principle

13 Leontyev A.N. Some problems of the psychology of art // Selected psychological works. - T.P. - M.: 1983. - P. 232.

pleasure”, helping to maintain mental well-being.

According to K. Jung, works of art reflect the extroverted or introverted attitude of the authors15.

C. Lombroso perceived literary creativity from the position of confirming diagnoses and interpreted works primarily as symptomatic. In this case, the literary text replaced the results of passing the waste products methodology16.

The interpretation of genius as something necessarily adjacent to insanity has gained popularity and provoked a number of studies of pathological manifestations of outstanding authors. In the 20s, there was a scientific direction - europathology, created by V.G. Sigalin, which studied the connection between giftedness and pathology. The identification of this relationship was also carried out by such an author as A.V. Shuvalov. His book “The Crazy Facets of Talent” is devoted to this issue. B.M. Teplov considered the characters of literary texts as carriers of the psychological traits of the author of the work17.

L.S. Vygotsky did not share the approach to considering a work of art as a reflection of the author’s personality. For L.S. Vygotsky, a work of art is a set of “aesthetic signs aimed at arousing emotions in people” (Vygotsky takes these words from the work of literary psychology researcher E. Hennequin). “... We do not interpret these signs as a manifestation of the mental organization of the author and his reader”18.

A. Morier proposed a typology of authors of literary works based on their psychological characteristics. A. Morier connects the types of styles of authors of literary texts with the types of personalities of the authors. V.P. Belyanin systematized various classifications literary authors according to the extraversion-introversion criterion19.

M.E. Burno developed creative self-expression therapy, designed for people with deep feelings of their own inferiority, anxiety and depressive disorders. The therapy was based on two

15 Jung K.G. Approach to the unconscious // Archetype and symbol. - M.: 1991.

16 Lombroso Ch. Genius and insanity. -SPb.: 1892. - S. 18 - 21.

17 Teploye B.M. Notes from a psychologist when reading fiction // Teploe B.M. Favorite works: in 2 vols. - M.: 1985.

18 Vygotsky L.S. Psychology of art. - M.: 1968. - P. 17.

19 Belyanin V.P. Fundamentals of psycholinguistic diagnostics

nostics. (Models of the world in literature). - M.: 2000.

ideas. The first idea is that a person suffering from psychological disorders can recognize and accept his own personality. The essence of the second idea is that any creativity is healing in nature, as it releases large quantities positive energy, which will allow the patient to alleviate his conditions through creative self-expression20. This therapy was not aimed at changing the patient’s character, but at his reconciliation with his essence and a more comfortable psychological state. A concept close to the “image of the author” is “author’s modality” - the expression in the work of the author’s attitude to what is displayed. Modality allows us to perceive a work of art as a whole, which is achieved not only by the perception of individual speech units, but also by determining their functions as part of the whole. The author's position is the embodiment of the meaning of the work and connects the entire system of speech structures into a single whole.

Speaking about the reflection of the author’s personality in a work of art, it is necessary to dwell on the concept of linguistic personality, developed in linguistics. Yu.N. Karaulov defines a “linguistic personality” as a set of abilities and characteristics of a person that determine his creation of speech works, which can vary in the degree of structural and linguistic complexity, in the depth and accuracy of the reflection of reality, in the target orientation. This definition combines a person’s abilities and the characteristics of the texts he creates. A linguistic personality can be considered at three levels: verbal-semantic, cognitive, motivational. The linguistic personality of the writer is objectified in his works of art. A work of artistic culture always represents a unity of content and form, reflected in terms such as “content form” and “formulation of content”21. The phenomenon of the worldview reflected in language is called the “linguistic picture of the world”, and in relation to a specific author - the individual linguistic picture of the world. This concept is more universal in comparison with Bakhtin’s concept of “intentional-accentual author’s plan”, which includes “the subject-semantic and expressive horizons of the narrator with his word”22. According to Yu.N. Karaulov, the picture of the world

20 Burno M.E. Creative self-expression therapy. - M.: 1999.

21 Odintsov V.V. Stylistics of the text. M.: 1980. - P. 35.

22 Bakhtin M. M. Questions of literature and aesthetics. Research different years. - M.: 1975. - P.127 - 128.

presented at the cognitive level of the linguistic personality. Concepts, ideas and concepts are units of the cognitive level. Concepts are always marked with values, since they form a picture of the world, which in turn reflects the hierarchy of values23.

Linguistic mentality, a concept important for revealing the problem of authorship, is a method of linguistic representation, including the relationship between the world and its linguistic representation. G.G. Pocheptsov identified two features of linguistic mentality, namely, which parts of the world turn out to be concepts and how these parts “cover” the world. G.G. Pocheptsov believed that the artistic reflection of the world is built on the principle of peaks, that is, those of its components that are most important for the author24.

The work of scientists in the field of art psychology described above allows us to draw several conclusions. Firstly, the personality of the author is reflected in the work of art he created. Secondly, the process of perceiving a work of artistic culture always represents indirect communication with its author. Thirdly, the process of perceiving a work of art, like any other communication, triggers many psychological mechanisms, the most important of which is

which is attribution - a mechanism that allows you to build an image of a partner. The tendency to attribute certain psychological properties to the author of a work can be understood through research into the attribution process as a type of subjective interpretation of the reasons for people’s behavior. This brings us back to the “Hennequin hypothesis,” which consists in the assumption that we value the works of authors who are close to us in their deep psychological characteristics and value guidelines higher than the works of those authors whose psychological characteristics are radically opposite to our own. The hypothesis has never been tested empirically, despite its many theoretical developments by various scientists. Probably, an empirical test of this assumption may be of independent scientific interest and will be carried out by us in future works.

23 Karaulov Yu.N. Russian linguistic personality and the tasks of its study. Published according to the introductory article in the collection. Language and personality. - M.: 1989. - P. 5.

24 Pocheptsov G.G. Linguistic mentality: A way of representing the world // Questions of linguistics. -1990. - No. 6. - P. 110 - 122.

REFLECTION OF THE PERSON OF THE AUTHOR IN A WORK OF ART

© 2013 M.S. Yankelevich" St. Petersburg State University

In this article different theoretical approaches to the problem of reflection of the author's psychological characteristics in art work are examined. Some psychological aspects of forming author's image through contact with his artwork are examined.

Key words: “author's image”, “author's modality”, “lingual personality”, “translation of meanings”, “artistic model of the world”.

Yankelevich Marina Sergeevna, Post-graduate student, Chair of General Psychology. E-mail: radaveselova@list. ru

Moscow 2008

The problem of the author has become, as many modern researchers recognize, central in literary criticism of the second half of the twentieth century. This is also connected with the development of literature itself, which (especially starting from the era of romanticism) increasingly emphasizes the personal, individual nature of creativity, and many different forms of “behavior” of the author in a work appear. This is also connected with the development of literary science, which strives to consider a literary work both as a special world, the result of the creative activity of the creator who created it, and as a certain statement, a dialogue between the author and the reader. Depending on what the scientist’s attention is focused on, they talk about image of the author in a literary work, about author's voice in relation to characters' voices. The terminology associated with the whole range of problems arising around the author has not yet become orderly and generally accepted. Therefore, first of all, we need to define the basic concepts, and then see how in practice, i.e. in a specific analysis (in each specific case), these terms “work”.

Of course, the author’s problem did not arise in the twentieth century, but much earlier. A modern scientist cites the statements of many writers of the past who amazingly turn out to be consonant - despite the complete dissimilarity of the same authors in many other respects. These are the sayings:

N.M. Karamzin: “The Creator is always depicted in creation and often against his will.”

M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin: “Every work of fiction, no worse than any scientific treatise, betrays its author with all his inner world.”

F.M. Dostoevsky: “In mirror reflection one cannot see how the mirror looks at the object, or, better to say, one can see that it does not look at all, but reflects passively, mechanically. A true artist cannot do this: whether in a painting, a story, or a piece of music, there will certainly be something different; he will reflect involuntarily, even against his will, he will express himself with all his views, with his character, with the degree of his development.”

The most detailed reflection on the author was left by L.N. Tolstoy. In the “Preface to the Works of Guy de Maupassant” he argues as follows: “People who are little sensitive to art often think that a work of art is one whole because the same persons act in it, because everything is built on the same premise.” or describes the life of one person. It's not fair. This is only how it seems to a superficial observer: the cement that binds every work of art into one whole and therefore produces the illusion of a reflection of life is not the unity of persons and positions, but the unity of the original moral attitude of the author to the subject. ...In essence, when we read or contemplate a work of art by a new author, the main question that arises in our soul is always this: “Well, what kind of person are you? And how are you different from all the people I know, and what can you tell me new about how we should look at our lives?” Whatever the artist depicts: saints, robbers, kings, lackeys - we look for and see only the soul of the artist himself" 1 .

Here we need to focus on two points that are especially important for us now. First: the unity and integrity of a literary work are directly related to the figure (image) of the author, moreover: he, the author, is the main guarantee of this unity (even, as we see, according to Tolstoy, to a greater extent than the heroes of the work and even then , what happens to them, i.e. the events that make up the plot of the work). And second. We have the right to ask ourselves the question: but to what extent is it legitimate to tell us about the author as a person (“come on, what kind of person are you?..”)? Looking ahead, let's say: probably to the same extent to which we sometimes talk about the human properties of the hero - which, of course, is assumed (since we are dealing with a literary work as a special kind of reality), and at the same time we perfectly “remember” that this reality is of a special kind and that a person in life is not at all the same as artistic image, even if it’s the same person. It is in this sense that we can only imagine the author as a person, and more precisely, we are dealing here with the image of the author, the image created by the entire work as a whole and arising in the mind of the reader as a result of a “response” creative act - reading.

“The word “author” is used in literary studies in several meanings. First of all, it means a writer - a real person. In other cases, it denotes a certain concept, a certain view of reality, the expression of which is the entire work. Finally, this word is used to designate certain phenomena characteristic of certain genres and genders” 2.

Noted B.O. Corman's triple use of the term can be supplemented and commented on. Most scientists distinguish between the author in the first meaning (also called the “real” or “biographical” author) and the author in the second meaning. This, to use another terminology, is the author as an aesthetic category, or the image of the author. Sometimes they talk here about the “voice” of the author, considering such a definition more legitimate and definite than the “image of the author.” For now, let us accept all these terms as synonyms in order to definitely and confidently distinguish the real, biographical author from that artistic reality, which is revealed to us in the work. As for the term “author” in the third meaning, the scientist here means that sometimes the narrator is called the author, the storyteller (in epic works) or the lyrical hero (in lyric poetry): this should be considered incorrect, and sometimes even completely incorrect.

To see this, you need to think about how the work is organized from a narrative point of view. Remembering that the author’s “presence” is not concentrated at one point in the work (the hero closest to the author, serving as a “mouthpiece” of his ideas, a kind of alter ego of the author; direct author’s assessments of the depicted, etc.), but is manifested in at all levels of artistic structure (from the plot to the smallest “cells” - tropes), - with this in mind, let’s look at how the author’s principle (the author) manifests itself in the subjective organization of the work, i.e. in the way it is constructed from a narrative perspective. (It is clear that in this way we will be talking primarily about epic works. The forms of manifestation of the author in lyric poetry and drama will be discussed later.)

Author, narrator, narrator, character

First of all, we need to distinguish the event that is told about in the work, and the event of the telling itself. This distinction, proposed for the first time in Russian literary criticism, apparently, by M.M. Bakhtin has now become generally accepted. Someone told us (the readers) about everything that happened to the heroes. Who exactly? This was approximately the path of thought that literary studies took in studying the problem of the author. One of the first special works devoted to this problem was the study of the German scientist Wolfgang Kaiser: his work entitled “Who Tells the Novel?” came out at the beginning of the twentieth century. And in modern literary criticism (not only in Russia) it is accepted different types denote narratives in German.

There are third-person narration (Erform, or, what is the same, Er-Erzählung) and 1st-person narration (Icherzählung). The one who narrates in the 3rd person, does not name himself (is not personified), we will agree to denote by the term narrator. The person who tells the story in the first person is called the narrator. (This use of terms has not yet become universal, but, perhaps, occurs among most researchers.) Let us consider these types in more detail.

Erform (“erform”), or “objective” narrative, includes three varieties, depending on how noticeable the “presence” of the author or characters is in them.

The author's own narration.

“The year after the birth of Christ 1918 was a great and terrible year, the second from the beginning of the revolution. It was full of sun in summer and snow in winter, and two stars stood especially high in the sky: the shepherd star - evening Venus and red, trembling Mars.

We immediately understand both the accuracy and some convention of the definition of “objective” narrative. On the one hand, the narrator does not name himself (“I”), he seems to be dissolved in the text and is not manifested as a person (not personified). This property of epic works is the objectivity of what is depicted, when, according to Aristotle, “the work, as it were, sings itself.” On the other hand, already in the very structure of phrases, inversion emphasizes and intonationally highlights evaluative words: “great”, “terrible”. In the context of the entire novel, it becomes clear that the mention of the Nativity of Christ, and of the “shepherd’s” Venus (the star that led the shepherds to the birthplace of Christ), and of the sky (with all the possible associations that this motif entails, for example, with “War”) and the world” by L. Tolstoy) – all this is connected with the author’s assessment of the events depicted in the novel, with the author’s concept of the world. And we understand the conventionality of the definition of “objective” narrative: it was unconditional for Aristotle, but even for Hegel and Belinsky, although they built the system literary families no longer in antiquity, like Aristotle, but in the 19th century, but based on the material precisely ancient art. Meanwhile, the experience of the novel (namely, the novel is understood as an epic of modern and contemporary times) suggests that the author’s subjectivity, the personal principle, also manifest themselves in epic works.

So, in the narrator’s speech we clearly hear the author’s voice, the author’s assessment of what is being depicted. Why don’t we have the right to identify the narrator with the author? This would be incorrect. The fact is that the narrator is the most important (in epic works), but not the only form of authorial consciousness. The author manifests himself not only in the narration, but also in many other aspects of the work: in the plot and composition, in the organization of time and space, in many other things, right down to the choice of means of small imagery... Although, first of all, of course, in the narration itself. The narrator owns all those sections of the text that cannot be attributed to any of the characters.

But it is important to distinguish between the subject of speech (the speaker) and the subject of consciousness (the one whose consciousness is expressed). It's not always the same thing. We can see in the narrative a certain “diffusion” of the voices of the author and the characters.

Not the author's own narration.

“Alexey, Elena, Talberg, and Anyuta, who grew up in Turbina’s house, and Nikolka, stunned by death, with a cowlick hanging over his right eyebrow, stood at the feet of the old brown Saint Nicholas. Nikolka’s blue eyes, set on the sides of a long bird’s nose, looked confused, murdered. From time to time he led them to the iconostasis, to the arch of the altar, drowning in twilight, where the sad and mysterious old god ascended and blinked. Why such an insult? Injustice? Why was it necessary to take away my mother when everyone moved in, when relief came?

God, flying away into the black, cracked sky, did not give an answer, and Nikolka himself did not yet know that everything that happens is always as it should be, and only for the better.

They performed the funeral service, went out onto the echoing slabs of the porch and escorted the mother through the entire huge city to the cemetery, where the father had long been lying under a black marble cross. And they buried mom. Eh... eh...”

Here, in the scene when the Turbins bury their mother, the voice of the author and the voice of the hero are combined - despite the fact (it is worth emphasizing this again) that formally this entire fragment of text belongs to the narrator. “A cowlick hanging over his right eyebrow,” “blue heads planted on the sides of a long bird’s nose...” - this is how the hero himself cannot see himself: this is the author’s view of him. And at the same time, “a sad and mysterious old god” is clearly the perception of seventeen-year-old Nikolka, as well as the words: “Why such an insult? Injustice? Why was it necessary to take away my mother...”, etc. This is how the voice of the author and the voice of the hero are combined in the narrator’s speech, up to the case when this combination occurs within one sentence: “The god flying into the black, cracked sky did not give an answer...” (zone of the hero’s voice) - “... and Nikolka himself didn’t know yet...” (author’s voice zone).

This type of narration is called non-authorial. We can say that here two subjects of consciousness are combined (the author and the hero) - despite the fact that there is only one subject of speech: the narrator.

Now M.M.’s position should become clear. Bakhtin about “author’s excess”, expressed by him in his 1919 work “Author and Hero in aesthetic activity" Bakhtin separates, as we would now say, the biographical, real author and the author as an aesthetic category, an author dissolved in the text, and writes: “The author must be on the border of the world he creates as an active creator of it... The author is necessary and authoritative for the reader , who treats him not as a person, not as another person, not as a hero... but as a principle which must be followed (only a biographical consideration of the author turns him into... a person defined in existence who can be contemplated). Inside the work for the reader, the author is a set of creative principles that must be implemented (i.e. in the mind of the reader who follows the author in the reading process - E.O.)... His individuation as a person (i.e. the idea of the author as a person, a real person - E.O.) is already a secondary creative act of the reader, critic, historian, independent of the author as the active principle of vision... The author knows and sees more not only in the direction in which the hero looks and sees, but in another, fundamentally inaccessible to the hero himself.. The author not only knows and sees everything that each hero individually and all the heroes together knows and sees, but also more than them, and he sees and knows something that is fundamentally inaccessible to them, and in this is always certain and stable excess the author’s vision and knowledge in relation to each character and all the moments of completion of the whole... work are found” 3.

In other words, the hero is limited in his horizons 4 by a special position in time and space, character traits, age and many other circumstances. This is how he differs from the author, who is, in principle, omniscient and omnipresent, although the degree of his “manifestation” in the text of the work may be different, including in the organization of the work from the point of view of narrative. The author manifests himself in every element of a work of art, and at the same time he cannot be identified with any of the characters or with any one side of the work.

Thus, it becomes clear that the narrator is only one of the forms of the author’s consciousness, and it is impossible to completely identify him with the author.

Improperly direct speech.

“Anfisa showed neither surprise nor sympathy. She didn't like these boyish antics of her husband. They are waiting for him at home, they are dying, they can’t find a place for themselves, but he rode and rode, but Sinelga came to his mind - and he galloped off. It’s as if this same Sinelga will fall through the ground if you leave there a day later.” (F. Abramov. Crossroads)

“Yesterday I drank a lot. Not exactly “in shreds”, but firmly. Yesterday, the day before yesterday and the third day. All because of that bastard Banin and his dearest sister. Well, they split you into your labor rubles! ...After demobilization, I moved with a friend to Novorossiysk. A year later he was taken away. Some bastard stole spare parts from the garage" (V. Aksenov. Halfway to the Moon) /

As you can see, with all the differences between the characters here, F. Abramov and V. Aksenov have a similar principle in the relationship between the voices of the author and the character. In the first case, it seems that only the first two sentences can be “attributed” to the author. Then his point of view is deliberately combined with Anfisa's point of view (or "disappears" in order to give close-up the heroine herself). In the second example, it is generally impossible to isolate the author’s voice: the entire narrative is colored by the hero’s voice, his speech characteristics. The case is especially difficult and interesting, because... the intelligentsia vernacular characteristic of the character is not alien to the author, as anyone who reads Aksenov’s entire story can be convinced of. In general, such a desire to merge the voices of the author and the hero, as a rule, occurs when they are close and speaks of the desire of writers to position themselves not as a detached judge, but as a “son and brother” of their heroes. M. Zoshchenko called himself the “son and brother” of his characters in “Sentimental Stories”; “Your son and brother” was the title of V. Shukshin’s story, and although these words belong to the hero of the story, in many ways Shukshin’s author’s position is generally characterized by the narrator’s desire to get as close as possible to the characters. In studies of linguistic stylistics of the second half of the twentieth century. this tendency (going back to Chekhov) is noted as characteristic of Russian prose of the 1960s - 1970s. The confessions of the writers themselves are consistent with this. “...One of my favorite techniques - it has even become, perhaps, repeated too often - is the author’s voice, which seems to be woven into the hero’s internal monologue,” admitted Yu. Trifonov. Even earlier, V. Belov thought about similar phenomena: “...I think that there is some thin, elusively shaky and rightful line of contact between the author’s language and the language of the depicted character. A deep, very specific separation of these two categories is just as unpleasant as their complete merging” 5.

Non-authorial narration and non-authorial direct speech are two varieties of Erform that are close to each other. If it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them sharply (and researchers themselves admit this difficulty), then we can distinguish not three, but two varieties of Erform and talk about what predominates in the text: “the author’s plan” or “the character’s plan” ( according to the terminology of N.A. Kozhevnikova), that is, in the division we have adopted, the author’s own narrative or two other varieties of Erform. But it is necessary to distinguish at least these two types of authorial activity, especially since, as we see, this problem worries the writers themselves.

Icherzä hlung – first person narration– no less common in the literature. And here one can observe no less expressive possibilities for the writer. Let's consider this form - Icherzählung (according to the terminology accepted in world literary studies; in Russian sound - “icherzählung”).

“What a pleasure it is for a third-person narrator to switch to the first! It’s like having small and inconvenient thimble glasses and suddenly giving up, thinking and drinking cold raw water straight from the tap” (O. Mandelstam. Egyptian Brand. L., 1928, p. 67).

To the researcher... this succinct and powerful remark says a lot. Firstly, it strongly recalls the special essence of verbal art (compared to other types of speech activity)... Secondly, it testifies to the depth of aesthetic awareness choice one or another leading form of narration in relation to the task that the writer has set for himself. Thirdly, it indicates the necessity (or possibility) and artistic fruitfulness transition from one narrative form to another. And, finally, fourthly, it contains recognition of a certain kind of inconvenience, which is fraught with any deviation from the uncorrectable explication of the author’s “I” and which, nevertheless, fiction for some reason neglects” 6 .

“Uncorrected explication of the author’s “I”” in the terminology of a modern linguist is a free, unrestrained direct author’s word, which O. Mandelstam probably had in mind in this particular case - in the book “Egyptian Brand”. But first-person narration does not necessarily presuppose precisely and only such a word. And here at least three varieties can be distinguished. Let us agree to call the one who is the bearer of such a narrative storyteller(unlike the narrator in Erform). True, in the specialized literature there is no unity regarding the terminology associated with the narrator, and one can find word usage that is the opposite of what we proposed. But here it is important not to bring all researchers to a mandatory consensus, but to agree on terms. In the end, it is not a matter of terms, but of the essence of the problem.

So, three important types of first-person narration - Icherzählung , distinguished depending on who the narrator is: author-narrator; a narrator who is not a hero; hero-storyteller.

1. Author-narrator. Probably, it was precisely this form of narration that O. Mandelstam had in mind: it gave him, a poet writing prose, the most convenient and familiar, and, moreover, of course, in accordance with the specific artistic assignment the opportunity to speak as openly and directly as possible in the first person. (Although one should not exaggerate the autobiographical nature of such a narrative: even in lyric poetry, with its maximum subjectivity compared to drama and epic, the lyrical “I” is not only not identical to the biographical author, but is not the only opportunity for poetic self-expression.) The brightest and a well-known example of such a narrative is “Eugene Onegin”: the figure of the author-narrator organizes the entire novel, which is structured as a conversation between the author and the reader, a story about how the novel is written (was written), which thanks to this seems to be created before the eyes of the reader. The author here also organizes relationships with the characters. Moreover, we understand the complexity of these relationships with each of the characters largely thanks to the author’s peculiar speech “behavior.” The author's word is capable of absorbing the voices of the characters (in this case, the words hero And character are used as synonyms). With each of them, the author enters into a relationship of either dialogue, polemic, or complete sympathy and complicity. (Let’s not forget that Onegin is the author’s “good... friend”; at a certain time they became friends, they were going to go on a trip together, i.e. the author-narrator takes some part in the plot. But we must also remember about the conventions of such a game, for example: “Tatiana’s letter is before me, / I cherish it sacredly.” On the other hand, one should not identify the author as a literary image and with the real - biographical - author, no matter how tempting it may be (a hint of a southern exile and some other autobiographical features).

Bakhtin apparently first spoke about this verbal behavior of the author, about the dialogical relationship between the author and the characters, in the articles “The Word in the Novel” and “From the Prehistory of the Novel Word.” Here he showed that the image of a speaking person, his words, is a characteristic feature of the novel as a genre and that heteroglossia, the “artistic image of language” 7 , even the many languages of the characters and the author’s dialogical relationship with them are actually the subject of the image in the novel.

Hero-storyteller. This is the one who takes part in events and narrates them; thus, the apparently “absent” author in the narrative creates the illusion of authenticity of everything that happens. It is no coincidence that the figure of the hero-storyteller appears especially often in Russian prose starting from the second half of the 30s of the 19th century: this may also be explained by the increased attention of writers to the inner world of a person (the confession of the hero, his story about himself). And at the same time, already at the end of the 30s, when realistic prose, the hero - an eyewitness and participant in the events - was called upon to postulate the “plausibility” of what was depicted. In this case, in any case, the reader finds himself very close to the hero, sees him as if in close-up, without an intermediary in the person of the omniscient author. This is perhaps the largest group of works written in the Icherzählung manner (if anyone wanted to make such a calculation). And this category includes works where the relationship between the author and the narrator can be very different: the closeness of the author and the narrator (as, for example, in “Notes of a Hunter” by Turgenev); complete “independence” of the narrator (one or more) from the author (as in “A Hero of Our Time,” where the author himself only has a preface, which, strictly speaking, is not included in the text of the novel: it did not exist in the first edition). In this series we can call “ Captain's daughter"Pushkin, many other works. According to V.V. Vinogradov, “the narrator is the speech creation of the writer, and the image of the narrator (who pretends to be the “author”) is a form of literary “acting” of the writer” 8. It is no coincidence that the forms of narration in particular and the problem of the author in general are of interest not only to literary scholars, but also to linguists, such as V.V. Vinogradov and many others.

The concept of point of view remains to be clarified, but now it is important to pay attention to two more points: the “absence” of the author in the work and the fact that all of it constructed as a story by a hero who is extremely distant from the author. In this sense, the absent author’s word, distinguished by its literary nature, appears as an invisible (but assumed) opposite pole in relation to the hero’s word – the characteristic word. One of the striking examples of a fairy tale work can be called Dostoevsky’s novel “Poor People”, built in the form of letters from a poor official Makar Devushkin and his beloved Varenka. Later, about this first novel, which brought him literary fame, but also caused reproaches from critics, the writer remarked: “They don’t understand how you can write in such a style. They are accustomed to seeing the writer’s face in everything; I didn't show mine. And they have no idea that Devushkin is speaking, not me, and that Devushkin cannot say otherwise.” As we see, this half-joking admission should convince us that the choice of the form of narration occurs consciously, as a special artistic task. In a certain sense, the tale is the opposite of the first form of Icherzählung we named, in which the author-storyteller reigns with full rights and about which O. Mandelstam wrote. The author, it is worth emphasizing this again, works in the tale with someone else’s word - the word of the hero, voluntarily renouncing his traditional “privilege” of an omniscient author. In this sense, V.V. was right. Vinogradov, who wrote: “A tale is an artistic construction in a square...” 10.

A narrator who cannot be called a hero can also speak on behalf of “I”: he does not take part in events, but only narrates about them. Narrator who is not a hero, appears, however, as part of the artistic world: he, too, like the characters, is the subject of the image. As a rule, he is endowed with a name, a biography, and most importantly, his story characterizes not only the characters and events about which he narrates, but also himself. Such, for example, is Rudy Panko in Gogol’s “Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka” - a figure no less colorful than the characters participating in the action. And his very manner of narration can perfectly clarify the above-mentioned position about the event of narration: for the reader this is truly an aesthetic experience, perhaps no less powerful than the events themselves that he is talking about and that happen to the heroes. There is no doubt that for the author, creating the image of Rudy Panka was a special artistic task. (From Mandelstam’s statement above, it is clear that in general the choice of a narrative form is never accidental; another thing is that it is not always possible to obtain the author’s interpretation of a particular case, but it is necessary to think about it every time.) This is how Gogol’s tale sounds:

“Yes, that was it, and I forgot the most important thing: when you, gentlemen, come to me, then take the straight path along the main road to Dikanka. I put it on the first page on purpose so that they could get to our farm faster. I think you’ve heard enough about Dikanka. And that’s to say that the house there is cleaner than some pasichnikov’s kuren. And there’s nothing to say about the garden: you probably won’t find anything like this in your St. Petersburg. Having arrived in Dikanka, just ask the first boy you come across, herding geese in a soiled shirt: “Where does the beekeeper Rudy Panko live?” - “And there!” - he will say, pointing his finger and, if you want, he will take you to the very farm. However, I ask you not to put your hands back too much and, as they say, to feint, because the roads through our farmsteads are not as smooth as in front of your mansions.”

The figure of the narrator provides the opportunity for a complex author’s “game”, and not only in fairy tale narration, for example, in M. Bulgakov’s novel “The Master and Margarita”, where the author plays with the “faces” of the narrator: he emphasizes his omniscience, possession full knowledge about the heroes and everything that happened in Moscow (“Follow me, reader, and only me!”), then he puts on a mask of ignorance, bringing him closer to any of the passing characters (they say, we didn’t see this, and what we didn’t see , we don’t know that). As he wrote in the 1920s. V.V. Vinogradov: “In a literary masquerade, a writer can freely change stylistic masks throughout one work of art” 11.

As a result, we present the definition of skaz given by modern scientists and taking into account, it seems, all the most important observations about skaz made by predecessors: “... a skaz is a two-voice narrative that correlates the author and the narrator, stylized as an orally pronounced, theatrically improvised monologue of a person, implying a sympathetic audience, directly related to the democratic environment or oriented towards this environment” 12.

So, we can say that in a literary work, no matter how it is constructed from the point of view of narration, we always find the author’s “presence”, but it is found to a greater or lesser extent and in different forms: in a 3rd person narration, the narrator is closest to the author, in the tale the narrator is the most distant from him. “The narrator in a tale is not only the subject of speech, but also the object of speech. In general, we can say that the stronger the narrator’s personality is revealed in the text, the more he is not only the subject of speech, but also its object” 13. (And vice versa: the more inconspicuous the narrator’s speech, the less specific it is, the closer the narrator is to the author.)

To better distinguish between the subject of speech (the speaker) and the object of speech (what is being depicted), it is useful to distinguish between the concepts subject of speech And subject of consciousness. Moreover, not only the appearance of the hero, an event (action), etc. can be depicted, but also - which is especially important for the genre of the novel and in general for all narrative prose - the speech and consciousness of the hero. Moreover, the hero’s speech can be depicted not only as direct, but also in refraction - in the speech of the narrator (be it the author, narrator or storyteller), and therefore in his assessment. So, the subject of speech is the speaker himself. The subject of consciousness is the one whose consciousness is expressed (transmitted) in the speech of the subject. It's not always the same thing.

The subject of speech and the subject of consciousness coincide. This includes all cases of the author’s direct word (the author’s narration itself). We also include here fairly simple cases when there are two subjects of speech and two subjects of consciousness in the text.

I will not tolerate the corrupter

Fire and sighs and praises

He tempted the young heart;

So that the despicable, poisonous worm

Sharpened a lily stalk;

To the two-morning flower

Withered still half-open.”

All this meant, friends:

I'm shooting with a friend.

As we can see, the signs of direct speech are indicated, and Lensky’s speech itself is separated from the author’s. The author's voice and the hero's voice do not merge.

A more complicated case. There is one subject of speech, but two consciousnesses are expressed (the consciousness of two): in this example, the author and the hero.

And his song was clear,

Like the thoughts of a simple-minded maiden,

Like a baby's dream, like the moon

In the deserts of the serene sky,

Goddess of secrets and tender sighs.

He sang separation and sadness,

AND something, And foggy distance,

And romantic roses...

Please note that here, in the last three verses, the author is clearly ironic about Lensky’s poetry: the words in italics are thus separated from the author as alien, and in them one can also see an allusion to two literary sources. (An allusion is a hidden hint at an implied, but not directly indicated literary source. The reader must guess which one.) “Fog in the distance” is one of the common romantic formulas, but it is possible that Pushkin also had in mind the article by V.K. Kuchelbecker 1824 “On the direction of our poetry, especially lyrical, in the last decade.” In it, the author complained that the romantic elegy had replaced the heroic ode, and wrote: “The pictures are the same everywhere: moon, which - of course - sad And pale, rocks and oak groves where they have never been, a forest behind which a hundred times one imagines the setting sun, the evening dawn, occasionally long shadows and ghosts, something invisible, something unknown, vulgar allegories, pale, tasteless personifications... in features - fog: fogs over the waters, fogs over the forest, fogs over the fields, fog in the writer’s head.” Another word highlighted by Pushkin - “something” - indicates the abstractness of romantic images, and perhaps even “Woe from Wit”, in which Ippolit Markelych Udushev produces a “scientific treatise” called “A Look and Something” - meaningless , empty essay.

Everything that has been said should lead us to an understanding of the complex, polemical relationship between the author and Lensky; In particular, this polemic relates not so much to the personality of the youngest poet, unconditionally beloved by the author, but to romanticism, to which the author himself had recently “paid tribute,” but with which he has now decisively parted ways.

Another more difficult question is: who owns Lensky’s poems? Formally – to the author (they are given in the author’s speech). Essentially, as M.M. writes. Bakhtin in the article “From the Prehistory of the Novel Word”, “poetic images... depicting Lensky’s “song” do not at all have a direct poetic meaning here. They cannot be understood as direct poetic images of Pushkin himself (although the formal characterization is given by the author). Here Lensky’s “song” characterizes itself, in its own language, in its own poetic manner. Pushkin’s direct characterization of Lensky’s “song” - it is in the novel - sounds completely different:

So he wrote dark And sluggishly...

In the above four lines, the song of Lensky himself sounds, his voice, his poetic style, but they are permeated here with the parodic and ironic accents of the author; Therefore, they are not isolated from the author’s speech either compositionally or grammatically. Before us really image Lensky's songs, but not poetic in the narrow sense, but typically novelistic image: this is an image of a foreign language, in this case an image of a foreign poetic style... The poetic metaphors of these lines (“like a baby’s dream, like the moon”, etc.) are not here at all primary means Images(what they would be like in a direct, serious song by Lensky himself); they themselves become here subject of the image, namely, a parody-stylizing image. This novel image someone else's style... in the system of direct author's speech... taken in intonation quotes, namely, parodic and ironic" 14 .

The situation is more complicated with another example from Eugene Onegin, which is also given by Bakhtin (and after him by many modern authors):

“Whoever lived and thought cannot

Do not despise people in your heart;

Whoever felt it is worried

Ghost of irrevocable days:

There's no charm for that

That serpent of memories

He is gnawing at remorse.

One might think that we have before us the direct poetic maxim of the author himself. But already the following lines:

All this often gives

Great charm to the conversation, -

(the conventional author with Onegin) cast a slight objective shadow on this maxim (i.e. we can and even should think that Onegin’s consciousness is depicted here - serves as an object - E.O.). Although it is included in the author’s speech, it is built in the area of action of Onegin’s voice, in Onegin’s style. Before us again is a novelistic image of someone else's style. But it was built a little differently. All the images in this passage are the subject of the image: they are depicted as Onegin’s style, as Onegin’s worldview. In this respect, they are similar to the images of Lensky's song. But, unlike this latter, the images of the given maxim, being the subject of the image, themselves depict, or rather, express the author’s thought, for the author largely agrees with it, although he sees the limitations and incompleteness of the Onegin-Byronic worldview and style. Thus, the author... is much closer to Onegin’s “language” than to Lensky’s “language”... he not only depicts this “language”, but to a certain extent he himself speaks this “language”. The hero is in the zone of possible conversation with him, in the zone dialogical contact. The author sees the limitations and incompleteness of the still fashionable Onegin language-worldview, sees his funny, isolated and artificial face (“Muscovite in Harold’s cloak”, “A complete vocabulary of fashionable words”, “Isn’t he a parody?”), but at the same time whole line he can express significant thoughts and observations only with the help of this “language”... the author really talking with Onegin..." 15.

3. The subjects of speech are different, but one consciousness is expressed. Thus, in Fonvizin’s comedy “The Minor,” Pravdin, Starodum, and Sofia essentially express the author’s consciousness. It is already difficult to find such examples in literature since the era of romanticism (and this example is taken from the lecture of N.D. Tamarchenko). Speeches of the characters in the story by N.M. Karamzin " Poor Lisa” also often reflect one thing – the author’s – consciousness.

So we can say that author's image, author(in the second of the three meanings above), author's voice– all these terms really “work” when analyzing a literary work. At the same time, the concept of “author’s voice” has a narrower meaning: we are talking about it in relation to epic works. The image of the author is the broadest concept.

Point of view.

The subject of speech (the speaker, the narrator) manifests himself both in the position he occupies in space and time, and in the way he names what is depicted. Various researchers distinguish, for example, spatial, temporal and ideological-emotional points of view (B. O. Korman); spatio-temporal, evaluative, phraseological and psychological (B.A. Uspensky). Here is B. Corman’s definition: “a point of view is a single (one-time, point-by-point) relationship of a subject to an object.” Simply put, the narrator (author) looks at what is depicted, taking a certain position in time and space and evaluating the subject of the image. Actually, an assessment of the world and man is the most important thing that the reader is looking for in a work. This is the same “original moral attitude to the subject” of the author that Tolstoy thought about. Therefore, summarizing the various teachings about points of view, let us first name the possible relationships in spatiotemporally. According to B.A. Uspensky, this is 1) the case when the spatial position of the narrator and the character coincide. In some cases, “the narrator is there, i.e. at the same point in space where a certain character is located - he is, as it were, “attached” to him (for a while or throughout the entire narrative). ...But in other cases the author should behind the character, but does not transform into him... Sometimes the place of the narrator can be determined only relatively” 2). The spatial position of the author may not coincide with the position of the character. Here the following are possible: sequential review - changing points of view; another case is “the author’s point of view is completely independent and independent in its movement; "moving position"; and finally, “the overall (overarching) point of view: the bird’s eye view.” You can also characterize the narrator’s position in time. “At the same time, the actual countdown of time (the chronology of events) can be carried out by the author from the position of some character or from his own position.” At the same time, the narrator can change his position, combine different time plans: he can, as it were, look from the future, run ahead (unlike the hero), he can remain in the hero’s time, or he can “look into the past” 16.

Phraseological point of view. Here the question of name: in the way this or that person is named, the namer himself is revealed most of all, because “the acceptance of this or that point of view... is directly determined by the attitude towards the person.” B.A. Ouspensky gives examples of how the Parisian newspapers referred to Napoleon Bonaparte as he approached Paris during his “Hundred Days.” The first message read: " Corsican monster landed in Juan Bay." The second news reported: " Ogre goes to Grasse." Third message: " Usurper entered Grenoble." Fourth: " Bonaparte occupied Lyon." Fifth: " Napoleon approaching Fontainebleau." And finally, sixth: “ His Imperial Majesty expected today in his faithful Paris."

And the way the hero is called also reveals his assessment by the author or other characters. “...very often in fiction the same person is called by different names (or is generally called in various ways), and often these different names collide in one phrase or directly close in the text.

Here are some examples:

"Despite the enormous wealth Count Bezukhov, since Pierre received it and received it, he felt much less rich than when he received his 10 thousand from the late count "...

“At the end of the meeting, the great master, with hostility and irony, made Bezukhov a remark about his ardor and that it was not only the love of virtue, but also the passion for struggle that guided him in the dispute. Pierre didn’t answer him..."

It is quite obvious that in all these cases the test uses several points of view, i.e. the author uses different positions when referring to the same person. in particular, the author can use the positions of certain characters (of the same work) who are in different relationships to the named person.

If we know what other characters are called this person(and this is not difficult to establish by analyzing the corresponding dialogues in the work), then it becomes possible to formally determine whose point of view is used by the author at one point or another in the narrative” 17.

In relation to lyric poetry, they talk about various forms of manifestation in it of the author's, subjective, personal principle, which reaches its utmost concentration in lyric poetry (compared to epic and drama, which are traditionally considered - and rightfully so - to be more “objective” types of literature). The term “lyrical hero” remains the central and most frequently used term, although it has its own certain boundaries and is not the only form of manifestation of authorial activity in lyric poetry. Various researchers talk about the author-narrator, the author himself, the lyrical hero and the hero of role-playing lyrics (B.O. Korman), about the lyrical “I” and in general about the “lyrical subject” (S.N. Broitman). A unified and final classification of terms that would fully cover the entire variety of lyrical forms and suit all researchers without exception does not yet exist. And in lyric poetry, “the author and the hero are not absolute values, but two “limits” towards which other subjective forms gravitate and between which are located: narrator(closer to the author’s plan, but not entirely coinciding with it) and narrator(endowed with authorial features, but gravitating towards the “heroic” plan)” 18.