The role of Catherine 2 in the life of Grinev. Reality and fiction in the images of Pugachev and Catherine II in the novel by A.S. Pushkin “The Captain's Daughter”

The images of Emelyan Pugachev and Empress Catherine II are symbols of power. We can say that these historical figures are at different poles, they are radically opposite.

Pushkin gave a real portrait of the empress in this episode: “She was in a white morning dress, a nightcap and a shower jacket. She seemed to be about forty years old. Her face, plump and ruddy, expressed importance and calmness, and her blue eyes and light smile had an inexplicable charm.”

The image of Catherine II, fair, merciful, grateful, was written by Pushkin with undisguised sympathy, fanned with a romantic aura. This is not a portrait real person, but a certain generalized image. Catherine is the shrine that the nobles defended in the war with Pugachev.

Catherine listens carefully to Masha Mironova and promises to look into her request, although the empress’s attitude towards the “traitor” Grinev is sharply negative. Having learned all the details of the case and being imbued with sincere sympathy for the captain’s daughter, Ekaterina has mercy on Masha’s fiancé and promises to take care of the girl’s material well-being: “... but I am indebted to the daughter of Captain Mironov. Don't worry about the future. I take it upon myself to arrange your condition.”

The Empress needs Grinev's innocence more than his guilt. Each nobleman who went over to Pugachev’s side harmed the noble class, the support of her throne. Hence Catherine’s anger (her face changed while reading the letter and became stern), which after Marya Ivanovna’s story “changes to mercy.” The queen smiles and asks where Masha is staying. She apparently makes a decision favorable to the petitioner and reassures the captain’s daughter.

Pushkin, giving the right to tell Grinev, forces him at the same time to report facts that allow us to draw our own conclusions. Ekaterina speaks kindly to Marya Ivanovna and is friendly with her. In the palace, she picks up the girl who has fallen at her feet, shocked by her “mercy.” She utters a phrase, addressing her, her subject, as her equal: “I know that you are not rich,” she said, “but I am indebted to the daughter of Captain Mironov. Don’t worry about the future. I take it upon myself to arrange your fortune " How could Marya Ivanovna, who from childhood was brought up in respect for the throne and royal power, perceive these words?

Pushkin wrote about Catherine that “her... friendliness attracted her.” In a small episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with the Empress through the lips of Grinev, he speaks about this quality of Catherine, about her ability to charm people, about her ability to “take advantage of the weakness of the human soul.” After all, Marya Ivanovna is the daughter of the hero, Captain Mironov, whose feat the queen knew about. Catherine distributed orders to officers who distinguished themselves in the war against the Pugachevites, and helped the orphaned noble families. Is it any wonder that she took care of Masha too. The Empress was not generous to her. The captain's daughter did not receive a large dowry from the queen and did not increase Grinev's wealth. Grinev's descendants, according to the publisher, i.e. Pushkin, “prospered” in a village that belonged to ten landowners.

Catherine valued the attitude of the nobility towards her and understood perfectly well what impression the “highest pardon” would make on the loyal Grinev family. Pushkin himself (and not the narrator) writes: “In one of the master’s wings they show a handwritten letter from Catherine II behind glass and in a frame,” which was passed down from generation to generation.

But Pugachev’s help to Grinev was much more real - he saved his life and helped save Masha. This is a striking contrast.

The author needed the image of Catherine II primarily for censorship reasons: it was necessary to contrast the attractive image of Pugachev with the image of another character of no less magnitude from the government camp, while presenting him in a positive light. The appearance of Catherine in the role of benefactor to the daughter of Captain Mironov contributed to a certain extent to the encryption of the true ideological meaning works. In addition, the plot of the family chronicle had to be brought to a traditional happy ending, and the introduction to the number characters Catherine was of great help here: she was the one who could cut through such a tightly drawn plot knot and lead the two heroes out of the impasse.

In the composition of the novel, the meeting of Masha Mironova with the empress leads to such a happy ending to the family chronicle of the Grinevs. This circumstance cannot but leave its mark on the entire character of the episode. Beautiful morning early autumn, Tsarskoye Selo park, linden trees illuminated by the sun, a lake and swans on it - this is the landscape at the beginning of the story about the first meeting with Catherine II. The portrait of the Empress, quickly sketched, is given in the same light, attractive tone.

This is followed by a dialogue between Masha and Catherine, then a second meeting in the palace with a majestic enfilade of empty, magnificent chambers - and the gracious empress, “having kindness to the poor orphan,” releases her. This is how the family chronicle ends happily. Of course, Catherine II could not have acted differently with the commandant’s daughter Belogorsk fortress, who selflessly died in the fight against the “villain” and “impostor”, the enemy of the landowner-autocratic power. In this sense, Pushkin does not deviate at all from the truth of life.

But we note that the story is told on behalf of Grinev and according to the impressions conveyed to him by Marya Ivanovna. Pushkin in no way seeks to deepen or reveal the image of Catherine. He is content with communicating, in essence, the external ideas remaining after two short meetings between the heroine of the novel and the empress. These ideas are naturally colored bright hues. About the essence of the autocratic power of the first landowner of the noble state, something could be gleaned from the content of the novel earlier: let’s remember the information about brutal reprisals against the people scattered across various chapters (for example, a mutilated Bashkir, an episode of a meeting with a floating gallows in the missing chapter), let’s remember the image noble camp (for example, the siege of Orenburg, the military council of General R., etc.).

It was impossible to reveal the image of Catherine II in the episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with her more deeply and, therefore, more realistically in a work intended for publication. Maybe that’s why Pushkin resorts to a kind of quotation: painting Catherine against the backdrop of Tsarskoye Selo park, he quite accurately conveys famous portrait Catherine, written by Borovikovsky. This is evidenced by a number of details: the Rumyantsev Obelisk (a monument in honor of the recent victories of Count Pyotr Aleksandrovich Rumyantsev), “a white dog of the English breed”, “a full and ruddy face” - everything is like in a portrait by Borovikovsky. The description of the ‘portrait’ made it possible to evoke in the reader the image of Catherine in a suitable plot situation lighting

Pushkin's true attitude towards Catherine II is not reflected in the episode of Masha Mironova's meeting with her in the novel. It is expressed in his notes in Russian history XVIII century. Pushkin mercilessly condemned domestic policy Catherine, noted her “cruel despotism under the guise of meekness and tolerance,” speaks of the merciless enslavement of the peasants, of torture in the secret chancellery, of the theft of the treasury by the empress’s favorites, of the hypocrisy of “Tartuffe in a Skirt and Crown.” We must not forget about all this either.

Convinced of Grinev’s innocence, Masha Mironova considers it her moral duty to save him. She travels to St. Petersburg, where her meeting with the Empress takes place in Tsarskoe Selo.

Catherine II appears to the reader as a benevolent, gentle and simple woman. But we know that Pushkin had a sharply negative attitude towards Catherine II. How can one explain her attractive appearance in the story?

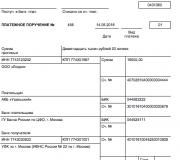

Let's look at the lifetime portrait of Catherine II, painted by the artist V.L. Borovikovsky in 1794. (In 1827, an engraving of this portrait appeared, made by the outstanding Russian engraver N.I. Utkin.) Here is how V. Shklovsky compares the portraits of Catherine II made by V.L. Borovikovsky and the narrator in the story “The Captain’s Daughter”: “In the portrait of Catherine depicted in the morning summer dress, in a night cap; near her feet there is a dog; behind Catherine there are trees and the Rumyantsev Obelisk. The Empress's face is full and rosy. The meeting with Marya Ivanovna should take place in the fall. Pushkin writes: “The sun illuminated the tops of the linden trees, which had turned yellow under the fresh breath of autumn.” Further, Pushkin reports: “She [Ekaterina] was in a white morning dress, a nightcap and a shower jacket.” The shower jacket made it possible not to change Catherine’s clothes, despite the cold weather... The dog from Borovikovsky’s painting also ended up in “The Captain’s Daughter”, it was she who first noticed Marya Ivanovna." There are discrepancies between the text and the image - the empress younger than years 20, dressed in white, not blue. The second version of the portrait is described - with the Rumyantsev Obelisk; most likely, Pushkin was inspired by the engraving, and not by the original, which Rumyantsev had and was difficult to view.

And here are the words from P.A. Vyazemsky’s article “On Karamzin’s Letters,” which V. Shklovsky cites: “In Tsarskoe Selo, Catherine must not be forgotten... The monuments of her reign here tell about her. Having laid the crown from her head and the purple from her shoulders, Here she lived as a homely and kind housewife. Here, it seems, you meet her in the form and attire in which she is depicted in famous painting Borovikovsky, even more famous for the beautiful and excellent engraving by Utkin."

We see that the portrait of V.L. Borovikovsky, the engraving of N.I. Utkin and the words of P.A. Vyazemsky express a noble, tender and admiring attitude towards the “gracious hostess” of Tsarskoe Selo.

Now let's turn to the story. As we know, Pushkin writes on behalf of the narrator, and the narrator - Grinev - narrates about the meeting of Marya Ivanovna with the Empress from the words of Marya Ivanovna, who, of course, recalled many times in later life the meeting that shocked her. How could these people devoted to the throne talk about Catherine II? There is no doubt: with naive simplicity and loyal adoration. “According to Pushkin’s plan,” writes literary critic P.N. Berkov, “obviously, Catherine II in” The captain's daughter"and should not be shown realistically, as a real, historical Catherine: Pushkin’s goal, in accordance with the form he chose for the notes of the hero, a loyal nobleman, was to portray Catherine precisely in the official interpretation: even Catherine’s morning disabiliy was designed to create a legend about the empress, as a simple, ordinary woman."

However, let’s see if in the episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with Ekaterina and in the description of the previous circumstances there is still an author’s attitude towards them. Let us recall the facts that took place from the moment Grinev appeared in court. We know that he stopped his explanations to the court about the real reason his unauthorized absence from Orenburg and this extinguished the “favor of the judges” with which they began to listen to him. Sensitive Marya Ivanovna understood why Grinev did not want to justify himself before the court, and decided to go to the queen herself to tell everything sincerely and save the groom. She succeeded. Now let's turn to the episode of the queen's meeting with Marya Ivanovna.

Grinev’s innocence became clear to Catherine from Marya Ivanovna’s story, from her petition, just as it would have become clear to the investigative commission if Grinev had finished his testimony. Marya Ivanovna told what Grinev did not say at the trial, and the queen acquitted Masha’s groom. So what is her mercy? What is humanity?

The Empress needs Grinev's innocence more than his guilt. Each nobleman who went over to Pugachev’s side harmed the noble class, the support of her throne. Hence Catherine’s anger (her face changed while reading the letter and became stern), which after Marya Ivanovna’s story “changes to mercy.” The queen smiles and asks where Masha is staying. She apparently makes a decision favorable to the petitioner and reassures the captain’s daughter.

Pushkin, giving the right to tell Grinev, forces him at the same time to report facts that allow us to draw our own conclusions. Ekaterina speaks kindly to Marya Ivanovna and is friendly with her. In the palace, she picks up the girl who has fallen at her feet, shocked by her “mercy.” She utters a phrase, addressing her, her subject, as her equal: “I know that you are not rich,” she said, “but I'm in debt in front of the daughter of Captain Mironov. Don't worry about the future. I take it upon myself to arrange your fortune." How could Marya Ivanovna, who from childhood was brought up in respect for the throne and royal power, perceive these words?

Pushkin wrote about Catherine that “her... friendliness attracted her.” In a small episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with the Empress through the lips of Grinev, he speaks about this quality of Catherine, about her ability to charm people, about her ability to “take advantage of the weakness of the human soul.” After all, Marya Ivanovna is the daughter of the hero, Captain Mironov, whose feat the queen knew about. Catherine distributed orders to officers who distinguished themselves in the war against the Pugachevites, and also helped orphaned noble families. Is it any wonder that she took care of Masha too. The Empress was not generous to her. The captain's daughter did not receive a large dowry from the queen and did not increase Grinev's wealth. Grinev's descendants, according to the publisher, i.e. Pushkin, “prospered” in a village that belonged to ten landowners.

Catherine valued the attitude of the nobility towards her and understood perfectly well what impression the “highest pardon” would make on the loyal Grinev family. Pushkin himself (and not the narrator) writes: “In one of the master’s wings they show a handwritten letter from Catherine II behind glass and in a frame,” which was passed down from generation to generation.

This is how “the legend of the empress was created as a simple, accessible to petitioners, an ordinary woman,” writes P.N. Berkov in the article “Pushkin and Catherine.”

May 19 2010

The fact that Pushkin recreated in the novel the features of the empress captured by Borovikovsky emphasized the official “version” of the portrait. Moreover, Pushkin pointedly renounced his personal perception of the empress and gave the reader a copy of the copy. Borovikovsky painted from living nature. It was enough for Pushkin to present a copy of the highly approved portrait. He didn't pretend live model, but dead nature. Catherine II in the novel is not a living person, but a “quote,” as Shklovsky wittily noted. From this secondary nature comes the cold that surrounds Catherine in Pushkin’s novel. The “fresh breath of autumn” has already changed the face of nature - the leaves of the linden trees have turned yellow, the empress, going out for a walk, put on a “sweat jacket”. Her face was “cold,” “full and rosy,” it “expressed importance and calm.” The “stern facial expression” that appeared during the reading of Masha Mironova’s petition is associated with the same coldness. This is even emphasized by the author’s remark: “Are you asking for? - said the lady with a cold look.” There is also coldness in Catherine’s actions: she starts a “game” with Masha, posing as a lady close to the court - she plays, not lives.

This depiction of Catherine II reveals Pushkin’s intention to contrast the image of the “peasant king” with the image of the ruling empress. Hence the contrast between these two figures. Pugachev’s mercy, based on justice, is contrasted with Catherine’s “mercy,” which expressed the arbitrariness of autocratic power.

This contrast, as always, was acutely, artistically realized and perceived by Marina Tsvetaeva: “The contrast between Pugachev’s blackness and her (Ekaterina P. - /'. M.) whiteness, his liveliness and importance, his cheerful kindness and her condescending, his peasant -ness and her ladyship could not help but turn away from her the child’s heart, food-loving and already committed to the “villain.”

Tsvetaeva doesn’t just set out her impressions, she analyzes and carefully argues her thesis about the contrast in the portrayal of Pugachev and Catherine II and Pushkin’s attitude towards these antipodes: “Against the fiery background of Pugachev - fires, robberies, blizzards, wagons, feasts - this one is in a cap and a shower jacket , on the bench, between all sorts of bridges and leaves, seemed to me like a huge white fish, white fish and even unsalted. (Catherine’s main feature is amazing insipidity.).”

And further: “Let’s compare Pugachev and Catherine in reality: “Come out, beautiful maiden, I will give you freedom. I am the sovereign. (leading Marya Ivanovna out of prison).” “Excuse me,” she said in an even more affectionate voice, “if I interfere, but I am at court...”

How much more regal in his gestures is a man who calls himself a sovereign than an empress who presents herself as a hanger-on.” Yu. M. Lotman is right when he objects to the roughly straightforward definition of Pushkin’s view of Catherine II. Of course, Pushkin did not create a negative Catherine, did not resort to satirical colors. But Pushkin needed the confrontation between Pugachev and Catherine II, such a composition allowed him to expose important truths about the nature of autocracy. Features of the depiction of Pugachev and Catherine II make it possible to understand on whose side Pushkin’s sympathies lie. “Does Pushkin love Catherine in The Captain’s Daughter?” asked. And she answered: “I don’t know. He is respectful to her. He knew that all this: whiteness, kindness, fullness - things were respectable. So I honored him." The final answer to the questions of why Pushkin introduced the image of Catherine into the novel and how he portrayed her is given by last scene- meeting of Masha Mironova with the Empress in the Tsarskoye Selo Garden. Here the reader will learn the true reasons why Catherine declared Grinev innocent. But this scene is important not only for understanding the image of Catherine: during the meeting, the character of the captain’s daughter is finally revealed and ends love line novel, since it was Masha who defended her.

To understand this it is important important scene it must be remembered that it was written with the expectation of the effect of the reader’s presence: Marya Ivanovna, for example, does not know that she is talking with the empress, but the reader already guesses; The “lady” accuses Grinev of treason, but the reader knows very well that this accusation is not based on anything. Pushkin considered it necessary to discover this technique: at the time of the conversation, he reports: Masha Mironova “fervently told everything that was already known to my reader.”

So, Marya Ivanovna, answering the “lady’s” question, informs her about the reason for her arrival in the capital. At the same time, the interlocutor’s favor towards the unknown girl is energetically motivated: the “lady” learns that in front of her is the orphan of Captain Mironov, an officer loyal to the Empress. (The lady seemed to be touched.) In this state, she reads Masha’s petition.

Pushkin creates another one emergency, instructing Grinev to record (according to Masha Mironova) everything that happened: “At first she read with an attentive and supportive look; but suddenly her face changed, and Marya Ivanovna, who followed all her movements with her eyes, was frightened by the stern expression of this face, so pleasant and calm for a minute.”

It is very important for Pushkin to emphasize the idea that, even putting on the mask of a private person, Catherine was not able to humble the empress within herself. “Are you asking for Grinev? - said the lady with a cold look. - The Empress cannot forgive him. He stuck to the impostor not out of ignorance and gullibility, but as an immoral and harmful scoundrel.”

Marya Ivanovna’s meeting with Catherine II reaches its climax after this rebuke from the “lady”: the captain’s daughter from a timid and humble petitioner turns into a brave defender of justice, the conversation becomes a duel.

- “Oh, that’s not true! - Marya Ivanovna screamed.

- - How untrue! - the lady objected, flushing all over.

- - It's not true, it's not true! I'll tell you."

What could she do? Insist on your unfair verdict? But under the current conditions this would look like a manifestation of reckless despotism. Such a depiction of Catherine would contradict the truth of history. And Pushkin could not agree to this. What was important to him was something else: to show first the injustice of Grinev’s conviction and the essentially demagogic pardon of him by Catherine II, and then - her forced correction of her mistake.

Marya Ivanovna is summoned to the palace. The “lady,” already appearing in the image of Empress Catherine II, said: “Your business is over. I am convinced of your fiancé’s innocence.” This statement is remarkable. Catherine II herself admits that she releases Grinev because he is innocent. And his innocence was proven by Masha Mironova, and this truth was confirmed by the reader. Therefore, correcting a mistake is not mercy. Pushkinists attributed mercy to Catherine II. In fact, the honor of freeing the innocent Grinev belongs to the captain’s daughter. She did not agree not only with the court’s verdict, but also with the decision of Catherine II, with her “mercy.” She ventured to go to the capital to refute the arguments of the empress who condemned Grinev. Finally, she boldly threw a bold word at the “lady” - “It’s not true!” entered into a duel and won it; By attributing “mercy” to Catherine, researchers impoverish the image of the captain’s daughter, robbing her of the main act in her life. In the novel, she was a “suffering” person, a faithful daughter of her father, who had internalized his morality of humility and obedience. “Wonderful circumstances” not only gave her the happiness of connecting with her beloved, they renewed her soul, her life principles.

Need a cheat sheet? Then save - "Catherine II and Masha Mironova in Pushkin's story "The Captain's Daughter". Literary essays!One of the works of Russian literature in which the image of Catherine the Great is created is “The Captain’s Daughter” by A.S. Pushkin, written in 1836. While creating the work, the writer addressed many historical sources, however, he did not follow exactly historical description: the image of Catherine the Great is subordinated in Pushkin to the general concept of the work.

Literary critic V. Shklovsky quotes words from an article by P.A. Vyazemsky “On Karamzin’s letters”: “In Tsarskoe Selo we must not forget Catherine... Monuments of her reign here tell about her. Having put the crown from her head and the purple from her shoulders, she lived here as a homely and kind housewife. Here, it seems, you meet her in the form and attire in which she is depicted in the famous painting by Borovikovsky, even more famous from the beautiful and excellent engraving by Utkin.” Further, V. Shklovsky notes that, in contrast to the nobility and Pugachev’s camp, depicted in the “realistic manner”, “Pushkin’s Catherine is deliberately shown in the official tradition” [Shklovsky: 277].

Now let's turn to the story. As we know, Pushkin writes on behalf of the narrator, and the narrator - Grinev - narrates the meeting of Marya Ivanovna with the Empress from the words of Marya Ivanovna, who, of course, recalled the meeting that shocked her many times in her later life. How could these people devoted to the throne talk about Catherine II? There is no doubt: with naive simplicity and loyal adoration. “According to Pushkin’s plan,” writes literary critic P.N. Berkov, “obviously, Catherine II in “The Captain’s Daughter” should not be shown realistically, like the real, historical Catherine: Pushkin’s goal is in accordance with his chosen form of notes of the hero, a loyal nobleman , it was to portray Catherine precisely in the official interpretation: even Catherine’s morning disabiliy was designed to create a legend about the empress as a simple, ordinary woman.”

The fact that Pushkin recreated in the novel the features of the empress, captured by the artist Borovikovsky, emphasized the official “version” of the portrait. Moreover, Pushkin demonstratively renounced his personal perception of the empress and gave the reader a “copy of a copy.” Borovikovsky painted from living nature. It was enough for Pushkin to present a copy of the highly approved portrait. He depicted not a living model, but a dead nature. Catherine II in the novel is not an image of a living person, but a “quote,” as Shklovsky wittily noted. From this secondary nature comes the cold that surrounds Catherine in Pushkin’s novel. The “fresh breath of autumn” has already changed the face of nature - the linden leaves turned yellow, the empress, going out for a walk, put on a “sweat jacket”. Her “cold” face, “full and rosy,” “expressed importance and calm.” The “stern facial expression” that appeared during the reading of Masha Mironova’s petition is associated with the same coldness. This is even emphasized by the author’s remark: “Are you asking for Grinev? - said the lady with a cold look.” There is also coldness in Catherine’s actions: she starts a “game” with Masha, posing as a lady close to the court; she plays, not lives.

This depiction of Catherine II reveals Pushkin’s intention to contrast this image of the ruling empress with the image of Pugachev, the “peasant king.” Hence the contrast between these two figures. Pugachev’s mercy, based on justice, is contrasted with Catherine’s “mercy,” which expressed the arbitrariness of autocratic power.

This contrast, as always, was acutely aware and perceived by Marina Tsvetaeva: “The contrast between Pugachev’s blackness and her (Catherine II’s) whiteness, his liveliness and her importance, his cheerful kindness and her condescending one, his masculinity and her ladylikeness could not help but disgust from her childish heart, one-loving and already committed to the “villain” [Tsvetaeva].

Tsvetaeva doesn’t just set out her impressions, she analyzes the novel and carefully argues her thesis about the contrast in the portrayal of Pugachev and Catherine II and Pushkin’s attitude towards these antipodes: “Against the fiery background of Pugachev - fires, robberies, blizzards, wagons, feasts - this one, in a cap and the shower jacket, on the bench, between all sorts of bridges and leaves, seemed to me like a huge white fish, a whitefish. And even unsalted. (Ekaterina’s main feature is amazing blandness)” [Tsvetaeva].

And further: “Let’s compare Pugachev and Catherine in reality: “Come out, beautiful maiden, I will give you freedom. I am the sovereign." (Pugachev leading Marya Ivanovna out of prison). “Excuse me,” she said in an even more affectionate voice, “if I interfere in your affairs, but I am at court...” [ibid.].

The assessment given to Ekaterina Tsvetaeva may be somewhat subjective and emotional. She writes: “And what a different kindness! Pugachev enters the dungeon like the sun. Catherine’s affectionateness even then seemed to me sweetness, sweetness, honeyedness, and this even more affectionate voice was simply flattering: false. I recognized and hated her as a lady patroness.

And as soon as it started in the book, I became sucking and bored, its whiteness, fullness and kindness made me physically sick, like cold cutlets or warm pike perch in white sauce, which I know I will eat, but - how? For me, the book fell into two couples, into two marriages: Pugachev and Grinev, Ekaterina and Marya Ivanovna. And it would be better if they got married like that!” [ibid].

However, one question that Tsvetaeva asks seems very important to us: “Does Pushkin love Ekaterina in The Captain’s Daughter? Don't know. He is respectful to her. He knew that all this: whiteness, kindness, fullness - things were respectable. So I honored you.

But there is no love - enchantment in the image of Catherine. All of Pushkin’s love went to Pugachev (Grinev loves Masha, not Pushkin) - only official respect remained for Catherine.

Catherine is needed so that everything “ends well” [ibid].

Thus, Tsvetaeva sees mainly repulsive features in the image of Catherine, while Pugachev, according to the poet, is very attractive, he “fascinates”, he looks more like a tsar than an empress: “How much more regal in his gesture is a man who calls himself a sovereign, than an empress posing as a hanger-on” [Tsvetaeva].

Yu.M. Lotman objects to the crudely straightforward definition of Pushkin’s view of Catherine II. Of course, Pushkin did not create negative image Catherine, did not resort to satirical colors.

Yu.M. Lotman explains the introduction of the image of Catherine II into the novel “The Captain's Daughter” by Pushkin’s desire to equalize the actions of the impostor and the reigning empress in relation to the main character Grinev and his beloved Marya Ivanovna. The “similarity” of the action lies in the fact that both Pugachev and Catherine II - each in a similar situation acts not as a ruler, but as a person. “In these years, Pushkin was deeply characterized by the idea that human simplicity forms the basis of greatness (cf., for example, “Commander”). It was precisely the fact that in Catherine II, according to Pushkin’s story, a middle-aged lady living next to the empress, walking in the park with a dog, allowed her to show humanity. “The Empress cannot forgive him,” says Catherine II to Masha Mironova. But not only the empress lives in her, but also a person, and this saves the hero, and prevents the unbiased reader from perceiving the image as one-sidedly negative” [Lotman: 17].

There is no doubt that in depicting the Empress, Pushkin must have felt especially constrained by political and censorship conditions. His sharply negative attitude towards “Tartuffe in a skirt and a crown,” as he called Catherine II, is evidenced by numerous judgments and statements. Meanwhile, he could not show Catherine in such a way in a work intended for publication. Pushkin found a double way out of these difficulties. Firstly, the image of Catherine is given through the perception of an eighteenth-century nobleman, officer Grinev, who, with all his sympathy for Pugachev as a person, remains a loyal subject of the empress. Secondly, in his description of Catherine, Pushkin relies on a certain artistic document.

As already mentioned, the image of the “lady” with the “white dog” that Masha Mironova met in the Tsarskoye Selo garden exactly reproduces famous portrait Catherine II Borovikovsky: “She was in a white morning dress, a nightcap and a shower jacket. She seemed to be about forty years old. Her face, plump and rosy, expressed importance and calmness, and her blue eyes and light smile had an inexplicable charm” [Pushkin 1978: 358]. Probably, any reader familiar with the indicated portrait will recognize Catherine in this description. However, Pushkin seems to be playing with the reader and forcing the lady to hide the fact that she is the empress. In her conversation with Masha, we immediately pay attention to her compassion.

At the same time, Pushkin is unusually subtle - without any pressure and at the same time in highest degree expressively - shows how this familiar “Tartuffe” mask instantly falls from Catherine’s face when she finds out what Masha is asking for Grinev:

“The lady was the first to break the silence. “Are you sure you’re not from here?” - she said.

Exactly so, sir: I just arrived from the provinces yesterday.

Did you come with your family?

No way, sir. I came alone.

One! But you are still so young.”

I have neither father nor mother.

Surely you are here on some business?

Exactly so, sir. I came to submit a request to the Empress.

You are an orphan: perhaps you complain about injustice and insult?

No way, sir. I came to ask for mercy, not justice.

Let me ask, who are you?

I am the daughter of Captain Mironov.

Captain Mironov! The same one who was the commandant in one of the Orenburg fortresses?

Exactly so, sir.

The lady seemed touched. “Excuse me,” she said in an even more affectionate voice, “if I interfere in your affairs; but I am at court; Explain to me what your request is, and maybe I will be able to help you.” Marya Ivanovna stood up and thanked her respectfully. Everything about the unknown lady involuntarily attracted the heart and inspired confidence. Marya Ivanovna took a folded paper out of her pocket and handed it to her unfamiliar patron, who began to read it to herself. At first she read with an attentive and supportive look; but suddenly her face changed, and Marya Ivanovna, who followed all her movements with her eyes, was frightened by the stern expression of this face, so pleasant and calm for a minute.

“Are you asking for Grinev?” - said the lady with a cold look. - “The Empress cannot forgive him. He stuck to the impostor not out of ignorance and gullibility, but as an immoral and harmful scoundrel.”

Oh, that's not true! - Marya Ivanovna screamed.

“How untrue!” - the lady objected, flushing all over” [Pushkin 1978: 357-358].

As we see, not a trace remains of the “inexplicable charm” of the stranger’s appearance. Before us is not a welcomingly smiling “lady,” but an angry, imperious empress, from whom it is useless to expect leniency and mercy. All the more clearly in comparison with this does the deep humanity emerge in relation to Grinev and his fiancée Pugacheva. It is precisely in this respect that Pushkin gets the opportunity both as an artist and bypassing the censorship slingshots to develop - in the spirit folk songs and tales about Pugachev - wonderful, with clearly expressed national-Russian features. It is no coincidence that V. Shklovsky notes: “The motive for Pugachev’s pardoning of Grinev is gratitude for a minor service that a nobleman once provided to Pugachev. The motive for Ekaterina’s pardon of Grinev is Masha’s petition.” [Shklovsky: 270].

Catherine's first reaction to Masha's request is a refusal, which she explains by the impossibility of forgiving the criminal. However, the question arises: why does the monarch, when administering justice, condemn based on denunciation and slander, and not try to restore justice? One answer is this: justice is alien to autocracy by nature.

However, Catherine II not only affirms the unfair verdict, she also, according to many researchers, shows mercy: out of respect for merit and old age She cancels the execution of her son Grinev's father and sends him to Siberia for eternal settlement. What kind of mercy is it to exile an innocent person to Siberia? But this, according to Pushkin, is the “mercy” of the autocrats, radically different from the mercy of Pugachev, it contradicts justice and is in fact the arbitrariness of the monarch. Need I remind you that Pushkin has his way? personal experience already knew what the mercy of Nicholas I boiled down to. With good reason, he wrote about himself that he was “fettered by mercy.” Naturally, there is no humanity in such mercy.

However, let’s see if in the episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with Ekaterina and in the description of the previous circumstances there is still an author’s attitude towards them. Let us recall the facts that took place from the moment Grinev appeared in court. We know that he stopped his explanations to the court about the true reason for his unauthorized absence from Orenburg and thereby extinguished the “favor of the judges” with which they began to listen to him. Sensitive Marya Ivanovna understood why Grinev did not want to justify himself before the court, and decided to go to the queen herself to tell everything sincerely and save the groom. She succeeded.

Now let us turn once again to the very episode of the meeting of the queen with Marya Ivanovna. Grinev’s innocence became clear to Catherine from Marya Ivanovna’s story, from her petition, just as it would have become clear to the investigative commission if Grinev had finished his testimony. Marya Ivanovna told what Grinev did not say at the trial, and the queen acquitted Masha’s groom. So what is her mercy? What is humanity?

The Empress needs Grinev's innocence more than his guilt. Each nobleman who went over to Pugachev’s side harmed the noble class, the support of her throne. Hence Catherine’s anger (her face changed while reading the letter and became stern), which after Marya Ivanovna’s story “changes to mercy.” The queen smiles and asks where Masha is staying. She, apparently, makes a decision favorable to the petitioner and reassures the captain’s daughter. Pushkin, giving the right to tell Grinev, forces him at the same time to report facts that allow us to draw our conclusions. Ekaterina speaks kindly to Marya Ivanovna and is friendly with her. In the palace, she picks up the girl who has fallen at her feet, shocked by her “mercy.” She utters a phrase, addressing her, her subject, as her equal: “I know that you are not rich,” she said, “but I am indebted to the daughter of Captain Mironov. Don't worry about the future. I take it upon myself to arrange your condition.” How could Marya Ivanovna, who from childhood was brought up in respect for the throne and royal power, perceive these words?

Pushkin wrote about Catherine that “her... friendliness attracted her.” In a small episode of Masha Mironova’s meeting with the Empress through the mouth of Grinev, he speaks about this quality of Catherine, about her ability to charm people, about her ability to “take advantage of the weakness of the human soul.” After all, Marya Ivanovna is the daughter of the hero, Captain Mironov, whose feat the queen knew about. Catherine distributed orders to officers who distinguished themselves in the war against the Pugachevites, and also helped orphaned noble families. Is it any wonder that she took care of Masha too. The Empress was not generous to her. The captain's daughter did not receive a large dowry from the queen and did not increase Grinev's wealth. Grinev's descendants, according to the publisher, i.e. Pushkin, “prospered” in a village that belonged to ten landowners.

Catherine valued the attitude of the nobility towards her and understood perfectly well what impression the “highest pardon” would make on the loyal Grinev family. Pushkin himself (and not the narrator) writes: “In one of the master’s wings they show a handwritten letter from Catherine II behind glass and in a frame,” which was passed down from generation to generation.

This is how “the legend was created about the empress as a simple, accessible to petitioners, an ordinary woman,” writes P.N. Berkov in the article “Pushkin and Catherine”. And that’s exactly how Grinev, one of the best representatives of the nobility, considered her late XVIII century.

However, in our opinion, Catherine II ultimately wanted to protect her power; if she lost the support of these people, then she would lose power. Therefore, her mercy cannot be called real, it is rather a trick.

Thus, in “The Captain's Daughter” Pushkin portrays Catherine in a very ambiguous way, which can be understood not only by some hints and details, but also by all artistic techniques which the author uses.

Another work that creates the image of Catherine, which we chose for analysis, is the story by N.V. Gogol's "The Night Before Christmas", which was written in 1840. In time, this story is separated from “The Captain’s Daughter” by only 4 years. But the story is written in a completely different way, in a different tone, and this makes the comparison interesting.

The first difference is related to portrait characteristic. Gogol’s portrait of Catherine has some kind of doll-like quality: “Then the blacksmith dared to raise his head and saw a short woman standing in front of him, somewhat portly, powdered, with blue eyes and at the same time with that majestically smiling appearance, which was so able to conquer everything and could only belong to one reigning woman.” Like Pushkin, blue eyes are repeated, but Gogol’s Catherine smiles “majesticly.”

The first phrase that Catherine utters shows that the empress is too far from the people: “His Serene Highness promised to introduce me today to my people, whom I have not yet seen,” said the lady with blue eyes, looking at the Cossacks with curiosity. “Are you well kept here?” she continued, coming closer" [Gogol 1940: 236].

Further conversation with the Cossacks makes it possible to imagine Catherine, at first glance, sweet and kind. However, let’s pay attention to the fragment when Vakula compliments her: “My God, what a decoration!” - he cried joyfully, grabbing his shoes. “Your Royal Majesty! Well, when you have shoes like these on your feet, and in them, your honor, hopefully, you can go and skate on the ice, what kind of shoes should your feet be? I think, at least from pure sugar” [Gogol 1040: 238]. Immediately after this remark follows the author’s text: “The Empress, who certainly had the most slender and charming legs, could not help but smile when hearing such a compliment from the lips of a simple-minded blacksmith, who in his Zaporozhye dress could be considered handsome, despite his dark face” [ ibid.]. It is undoubtedly permeated with irony, which is based on alogism (remember, “a short woman, somewhat portly”).

But even more irony is contained in the fragment describing the end of the meeting with the queen: “Delighted by such favorable attention, the blacksmith already wanted to ask the queen thoroughly about everything: is it true that kings eat only honey and lard, and the like - but, having felt, that the Cossacks were pushing him in the sides, he decided to remain silent; and when the empress, turning to the old people, began to ask how they lived in the Sich, what customs there were, he, moving back, bent down to his pocket, said quietly: “Take me out of here quickly!” and suddenly found himself behind a barrier” [ibid.]. The meeting ended seemingly at the behest of Vakula, but Gogol’s subtext is this: it is unlikely that the empress would listen with sincere attention to the life of the Cossacks.

The background on which Catherine appears is also different in the works. If Pushkin has this beautiful garden, creating a feeling of calm and tranquility, then for Gogol it is the palace itself: “Having already climbed the stairs, the Cossacks passed through the first hall. The blacksmith timidly followed them, fearing at every step he would slip on the parquet floor. Three halls passed, the blacksmith still did not cease to be surprised. Entering the fourth, he involuntarily approached the picture hanging on the wall. It was the Most Pure Virgin with the Baby in her arms. “What a picture! what a wonderful painting! - he reasoned, - it seems he’s talking! seems to be alive! and the Holy Child! and my hands were pressed! and grins, poor thing! and the colors! My God, what colors! here the vokhas, I think, weren’t even worth a penny, it’s all fire and cormorant: and the blue one is still burning! important work! the soil must have been caused by bleivas. As surprising as these paintings are, however, this copper handle,” he continued, going up to the door and feeling the lock, “is even more worthy of surprise.” Wow, what a clean job! All this, I think, was done by German blacksmiths for the most expensive prices...” [Gogol 1978: 235].

Here, what attracts attention is not so much the surrounding luxury itself, but rather the thoughts and feelings of the petitioners: the blacksmith “follows timidly” because he is afraid of falling, and the works of art decorating the walls raise the assumption that all this was done by “German blacksmiths, for the most expensive prices.” This is how Gogol conveys the idea that ordinary people and those in power seem to live in different worlds.

Together with Ekaterina, Gogol portrays her favorite Potemkin, who is worried that the Cossacks would not say anything unnecessary or behave incorrectly:

“Will you remember to speak as I taught you?

Potemkin bit his lips, finally came up himself and whispered imperiously to one of the Cossacks. The Cossacks rose up” [Gogol 1978: 236].

The following words of Catherine require special comment:

“- Get up! - the empress said affectionately. - If you really want to have such shoes, then it’s not difficult to do. Bring him the most expensive shoes, with gold, this very hour! Really, I really like this simplicity! “Here you are,” the empress continued, fixing her eyes on a middle-aged man standing further away from the others with a plump, but somewhat pale face, whose modest caftan with large mother of pearl buttons showed that he was not one of the courtiers - a subject worthy of your witty pen! [Gogol 1978: 237].

Catherine shows the satirical writer what he should pay attention to - simplicity ordinary people, and not on the vices of those in power. In other words, Catherine seems to switch the writer’s attention from statesmen, from the state (power is inviolable) to the small “oddities” of ordinary, illiterate people.

Thus, in Gogol’s work, Catherine is depicted in to a greater extent satirically than Pushkin.

CONCLUSIONS

The study allowed us to draw the following conclusions:

1) the study of historical and biographical materials and their comparison with works of art gives reason to say that there is an undoubted dependence of the interpretation of historical and biographical facts related to the life of the empresses on the peculiarities of the worldview of the authors of these works;

2) different assessments of the activities of the empresses, presented in works of art, - from categorically negative to clearly positive, bordering on delight, is due, firstly, to the complexity and contradictory nature of the characters of the women themselves, and secondly, moral principles authors of works and their artistic priorities; Thirdly, existing differences in stereotypes of assessment of the personality of these rulers by representatives of different classes;

3) in the fate of Cixi and Catherine II there are some common features: they went big and hard way to power, and therefore many of their actions from a moral point of view are assessed far from unambiguously;

4) artistic comprehension contradictory and ambiguous figures of the great empresses Cixi and Catherine II in the works of historical prose of China and Russia contributes to a deeper understanding of the significance of the role of the individual in historical process and understanding the mechanisms of formation of a moral assessment of their actions at a certain historical period of time.