All school essays on literature. Gogol's innovation in the comedy "The Inspector General"

The comedy “The Inspector General” is notable for the fact that it showed the innovation of Gogol the playwright. As you know, the plot of the comedy about a passing ordinary official, mistaken in the provinces for an important person, was suggested to Gogol by Pushkin. The writer began working on the play in 1835; “The Inspector General” was staged for the first time in April of the same year, but Gogol continued to polish the text of the work until 1851 (it was at this time that his last edit dates back to).

Gogol defined the concept of his work as follows:“In The Inspector General, I decided to collect in a heap all the bad things in Russia that I knew then, all the injustices that are done in those places and in those cases where justice is most required from a person, and at one time laugh at everything.”

The theme of the work can also be called innovative to some extent. This is an exposure of the bureaucratic and bureaucratic system of Russian life.

Unusual and social conflict“The Inspector General”, expressed in the disclosure of internal inconsistency, worthlessness, insolvency and absurdity social order. Behind the visible, immediate conflict lies another, broader one: the conflict between high, positive ideal, expressing the patriotic public consciousness of advanced Russia, and the realities of Russian life.

N.V. Gogol sought to update the plot of the play, so in The Inspector General there is no traditional plot: the expectation of the auditor, fear and fear of exposure - this is what becomes the plot.

Gogol renews the intrigue: usually the action was based on a love affair or the conscious deception of the hero actively leading the intrigue (rogue, womanizer). Khlestakov is not plotting any intrigue; he freely surrenders to the flow of events.

Gogol's innovation was also evident in the peculiarities of the denouement: the author did not take the path of traditional punishment for the perpetrators of a comedy incident. The famous “silent scene” affects the interests of everyone: in the finale of the work, Gogol brings all the characters onto the stage and makes them fall into “petrification” for two or three minutes. This allows the playwright to focus the viewer’s attention on the action itself and allows for a variable interpretation of the ending: a real inspector has arrived and the city will be met with well-deserved retribution; someone has arrived who is associated among the residents with heavenly punishment, which everyone fears; it was not the inspector who arrived, but important official traveling accompanied by a gendarme; a real auditor has arrived, but the audit will go smoothly and everything will end happily, as always. The silent scene is symmetrical to the beginning of the play - this is the general denouement.

In pre-Gogol dramaturgy art world The play assumed the presence of two poles - positive and negative. The world of the heroes of The Inspector General is homogeneous, there is no positive pole in it.

Collective, collectively comedy is the image of a city with its little king-mayor and officials representing different aspects of social and economic life: justice (Lyapkin-Tyapkin), social security (Strawberry), public education (Kholopov), post office (Shpekin), punitive authorities (Derzhimorda) and so on. The abuses and injustices of officials outlined in The Inspector General provincial town expose the lawlessness of the entire system government controlled country and at the same time show the personal participation of each of them in everyday outrages. The mayor, who deceived three governors, is in his own way a very smart and active person, able to both “give” and “take,” shamelessly steals government money and robs the population. The quarterly Derzhimorda takes “beyond his rank,” the caretaker of charitable institutions, Strawberry the rogue, embezzler and informer, the liberal judge Tyapkin-Lyapkin takes bribes “with greyhound puppies,” and so on. All of them, from the author’s point of view, must bear personal responsibility for their actions.

55. Dramatic innovation n.V. Gogol in the comedy "The Inspector General".

Answer: Gogol was in love with theater since childhood. He saw his father's comedies. Kapnist lived not far from Gogol. At the Nizhyn Lyceum, Gogol played roles. Gogol himself was a theatrical person. His prose was characterized by theatricality. Gogol organically approached dramaturgy. In 1833, the idea of the comedy “Vladimir of the Third Degree” arose, connected with the madness of an official, creating a space for unusual Gogol heroes. But the idea was followed by “Little Comedies” (by analogy with “Little Tragedies”: “Litigation”, “The Morning of a Man”, “Lackey”. Then, from the idea of a comedy about a game, the play “Players” was born. The fear of marriage gave rise to the comedy “Marriage” Gogol created his own theater.In his articles “Theatrical Travel”, “The St. Petersburg Stage”, he created the theory of theater.

Gogol believed that Russian comedy has rich traditions high comedy, prepared by Fonvizin and Griboyedov. He considered the clash of characters important. The Gogol Theater is a theater of bright characters. The basis of action is social relations, “the electricity of rank.” He believed that the word organizes comedic action. Gogol's original expression of words is laughter. His laughter cleanses and revives. Drama for him is missionary, creating his own world. Gogol first poses the problem of a special “mirror”. He believed that the theater performs an important educational function, compared the theater to a university. Gogol was deeply connected with Aristophanes.

The high purpose of the theater for Gogol was associated with comedy. Gogol considered the theater a democratic institution. The core of Gogol's aesthetics is laughter. Gogol reveals the ambivalence of laughter.

The premiere of The Inspector General in St. Petersburg at the Alexandrinsky Theater took place on April 19, 1836 and became available to the entire public. The emperor himself was present at the premiere. Nicholas I felt the satirical overtones, and the writer’s contemporaries (“Pushkin’s circle”) felt the social significance of comedy. Mass public I didn’t really take to The Inspector General. Gogol considered the performance a failure. In “Theatrical Travel” he gives an auto-review of his work and leaves Russia.

The play is named after an off-stage character. He is not mentioned in the list characters, he appears only at the beginning and at the end. He is not there, but he is dissolved in the space of comedy in the person of the false auditor and the space of the auditor. The auditor is a kind of symbol. This word contains the semantics of vision. The whole intrigue lies in the fact that there is an auditor, but he is not there.

"The Inspector General" is a five-act comedy. Gogol created truly social comedy. Events are developing in the form of a formidable cleansing. For Gogol, the image of high comedy is important. Five acts include 51 phenomena. Dynamics of action is created. The silent scene is the key to understanding Gogol's catharsis.

Epigraph – folk proverb. The epigraph brings the text to life. In the first edition there was no epigraph in the text. The epigraph focuses on the social meaning of the action. It contains the semantics of a mirror - a stage mirror into which Gogol makes the audience look. Dialogue with the audience is very important. Mirror - a look into your soul.

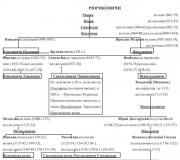

Gogol has 25 named characters. They form a hierarchy, in the center of which is the mayor. All members of the city government leave him. Khlopov correlates with the image of a donkey, Lyapkin-Tyapkin personifies refereeing. Among the 25 characters, only 5 are women. Male characters have an advantage, so love affairs are not decisive.

Gogol’s chronotope is “the combined city of the entire national team,” the quintessence of Russian existence. A window to the world opens through the city. Troika is a worldwide image for Gogol, this is the time of Gogol’s life. Gogol calculates time in minutes. Then time freezes, then pulsates, then fades to nothing. Reading Khlestakov’s letter is a stop of time, recorded in a silent scene. Playing with time is fundamental for Gogol, since absurdity knows no time.

In The Inspector General there is a conflict of laughter and fear. Conflict defines mirage intrigue. Gogol's city is the kingdom of the absurd. The “Perepetua effect” is created. Appearance imaginary auditor creates an absurd situation. Khlestakov turns into an impostor. The heart of the situation is deception and a general atmosphere of fear. Fear is personified - in the nominations of the characters, the interjection “an” is visible, meaning both “maybe” and “here, take a bite.”

The main engine of intrigue is Khlestakov. In the list of characters, Khlestakov is in the middle. This is an object of influence, an invented character. He alone doesn’t think about what he says. He's an actor and doesn't have many of his own lines. He continues the tradition of comedic braggadocio, but for him deception is an art. A whole image of “Khlestakovism” is created: hypocrisy and lies, absurdity. Khlestakov improvises on ready-made plots. The whole action is based on bribes. Petitioners turn into extortionists. The bribe-taker is formed from an impostor. He also benefits from intimate situations. And Gogol makes this scene incredibly comical. The situation is given a cosmic overtones. The situation is humanized. Tears imperceptibly invade an absurd situation. Gogol sees in heroes human souls. In the farewell scene, the music of a voice appears in which pain sounds.

The figure of Khlestakov largely determines the original synthesis of high comedy and absurd comedy. He is a capacitor of mirage intrigue. Sinyavsky defined “The Inspector General” as two turns of a key, one of which is a mirage, and the other is human existence. “The Inspector General” is a celebration of theatricality, but behind the theatricality sounds the living voice of a man crushed by existence.

The fifth act synthesizes the absurdity of existence to the greatest extent. Khlestakov’s truth shocked everyone, it resurrects the heroes. The reading of the letter ends with a silent scene, a kind of sixth act. Gogol attached symbolic meaning to this scene. The silent scene refers to “Boris Godunov”, but this is a judgment of the soul. A symbolic resurrection and insight occurs. The mayor and 12 acting figures - parodia sacra, a reduction in the biblical image of Christ and the 12 apostles. Laughter revives people's souls.

The innovation of The Inspector General is that the play marked the beginning of a new type of comedy - a comedy of social mores and characters.

The new social content of the play required

new artistic embodiment,

Therefore, Gogol moves away from the existing “comedy of errors”

and "sitcoms" and creates new type dramas.

How does this novelty manifest itself?

If we talk about the composition of the work,

then, first of all, it is the courage of the plot.

The first phrase about the arrival of the auditor causes everyone to

shock and gives rise to fear, which brings everyone together and deprives common sense.

The ending of the play corresponds to the unusually bold premise.

First the postmaster comes with the news that the official

whom everyone took for an auditor, was not an auditor,

and then, at the height of passions, a gendarme appears,

which in one phrase makes a stunning impression

and unleashes the action.

We can talk about double decoupling.

Looking at the composition, we see that one situation is

the beginning and end of the play, the beginning and the denouement.

But if at the beginning of the play the message about the auditor causes a flurry of activity

and general unity, then in the end the postmaster’s news first separates everyone,

and the appearance of the gendarme again unites, but at the same time deprives movement

and leads to petrification.

Comedy comes full circle.

In addition to the novelty of the beginning and ending, the novelty of the general structure of the dramatic action, which consistently, from beginning to end, follows from the characters, is also interesting.

N.V. Gogol’s desire for generalization resulted, according to his own definition,

in the "prefabricated city of all dark side»

This city is consistently hierarchical, its structure is pyramidal - “citizenship - merchants - officials - city landowners - the mayor at the head.”

Only Khlestakov and Osip stand outside the city.

The choice of characters is based on the desire to cover as many sides as possible public life and administration (judicial proceedings, education, health care, postal services, social security, police). Of course, the structure of the city is not reproduced entirely accurately, but the author did not need this

The “prefabricated city” is integral in itself, and at the same time, the boundary between it and the space outside the “walls” of the city is blurred, which is also an innovation

In “The Inspector General” (in contrast to the closed space of the same “Minor”) one gets the feeling that the norms of such a life are ubiquitous.

Khlestakov.

This is not the traditional image of a rogue, to which drama is accustomed, this is a new type, a new phenomenon in literature, which later became common noun.

The innovation of Gogol's dramatic solutions lay, first of all, in the fact that he left the place of the ideal in the conflict of The Inspector General vacant. The classical tendency of contrasting the negative with the positive, which existed at that time, was revised by the author. Gogol does not simply change the component antitheses.

Subject artistic comprehension become the characters of officials, generalizing social types and by the very fact of their existence exposing the bureaucratic system. At the same time, the grotesque is the most effective form of condemnation of the Russian reality of that time.

Here's more material on the topic

This video lesson is dedicated to discussing the topic “Innovation of Gogol, the playwright (based on the comedy “The Inspector General”).” You can learn a lot interesting details about the history of the creation and republication of this play. Together with the teacher, you will be able to analyze in great detail and subtly how the innovation of Gogol, the playwright, was manifested in The Inspector General.

The first printed edition was published in 1836 (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Printed edition of “The Inspector General” ()

In April 1836, the play premiered in Alexandrinsky Theater(Fig. 3), and in May - at the Maly Theater in Moscow.

Rice. 3. Alexandrinsky Theater ()

The second edition is published in 1841, and the final edition in 1842. Gogol changed his lines, revised them, explained them, commented on them and inserted the mayor’s wonderful phrase:

“There will be a clicker, a paper maker, who will insert you into a comedy. That's what's offensive! Rank and title will not be spared, and everyone will bare their teeth and clap their hands.”

Wonderful poet and the critic Apollo Aleksandrovich Grigoriev (Fig. 4) spoke about the plot of “The Inspector General”:

"This is a mirage of intrigue."

Rice. 4. A.A. Grigoriev ()

And this “mirage intrigue” appears repeatedly in Gogol’s works. For example, in the play “Marriage”, where Podkolesin both wants and does not want to get married, he last moment jumps out of the window just before the wedding, scared of marriage.

"The Inspector General" is a play about how in county town the inspector arrives. In the end it turns out that he is not an auditor at all. This is not an auditor, this is a dummy who was mistaken for an auditor.

In “Dead Souls” (Fig. 5) Chichikov goes to buy peasants. It turns out that he is not buying peasants, but lists of dead peasants.

Rice. 5. “Dead Souls” ()

This is a mirage, some kind of ghost, some kind of phantom, something unreal.

But Gogol’s predecessors encountered the situation of an imaginary auditor many times. This is best said by Yuri Mann. Here is one example he mentions. There was a writer Kvitka-Osnovyanenko (Fig. 6), who in 1827 wrote the play “A Visitor from the Capital, or Turmoil in a District Town.” This play will be published in 1842, after The Inspector General. But, according to some, Gogol could have known it from the manuscript.

Rice. 6. G. F. Kvitka-Osnovyanenko ()

In the play, a certain character comes to the district town, "metropolitan thing", who begins to pose as an auditor. It's easy to imagine how all this happens next. But the uniqueness of Gogol’s play is that Khlestakov does not pretend to be an auditor. The question arises: why were they deceived, why did they mistake Khlestakov for an auditor?

There may be more than one answer to this question. Belinsky says that it’s all about the mayor’s sick conscience. Yuri Vladimirovich Mann examines this in great detail and very subtly (Fig. 7).

He says that in this absurd world everything is absurd. After Chmykhov’s letter, all officials are already expecting the auditor. But why Khlestakov? You probably remember that Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky come running (Fig. 8) and say:

“Why! Of course he is! He doesn’t pay money, he doesn’t go anywhere. When we were driving with Pyotr Ivanovich, he looked into the plates. Why not an auditor? Inspector."

Rice. 8. Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky ()

The absurd world, the world of lies, hypocrisy (after all, the mayor deceived three governors), collides with the sincerity, with such unconscious lies of Khlestakov. This is where the plot of one of the best Russian plays arises.

The deception is revealed only in the fifth act, when the postmaster opens Khlestakov’s letter to Tryapichkin and finds out that Khlestakov is not only not an auditor, not authorized and not a person, but in general “neither this nor that, the devil knows what it is”.

But this is not enough. At the end of the play, a gendarme appears on the threshold with a message:

“An official who arrived from St. Petersburg demands everyone to come to him. He was staying at a hotel."

In general, Gogol was clearly dissatisfied with the modern theatrical repertoire: pranks of lovers, clever servants, vaudeville, melodramas (as a rule, borrowed or based on someone else's plot). Gogol constructs his play fundamentally differently.

In "Dead Souls" he says:

“Laughter visible to the world through invisible tears, unknown to him.”

He laughs at his heroes, but he is also scared that people come to this, it’s hard for him.

Fear is the force, the feeling that can unite everyone in this comedy. Moreover, it is clear what the mayor is afraid of, what the officials are afraid of. As Mann well proves, they are not afraid of exposure, they are afraid that they will not be lucky, they will not be able to deceive the auditor, they will not be able to correctly play the game that the auditor is forcing on them. But Dobchinsky is also afraid. And when Anna Andreevna says: “What do you have to be afraid of? You don’t serve", Dobchinsky answers: “When a nobleman speaks, you feel fear”.

In traditional comedy, evil is contrasted with good, and satirical heroes are contrasted with positive heroes. But Gogol doesn’t have this. Please note that city officials NN* They are absolutely not afraid of exposure, they are afraid of not pleasing. All concerns are concerns about form. They think that they need to put clean caps on the sick, sweep the street from the hotel to the hospital, they need to put up a straw pole (Fig. 9).

Rice. 9. Officials ()

It is no coincidence that Gogol not only does not give a positive hero, but he shows sins in his heroes. It is especially important to re-read the warning for gentlemen actors when Gogol explains the character of a particular character:

"Governor(Fig. 10) - a character who, like everyone else, has sins, for there is no person who does not have some sins.”

Rice. 10. Mayor ()

Another very important feature"The Inspector General" that distinguishes it from other comedies is its lack of love intrigue. Comedies are very often built on the vicissitudes of relationships between young lovers (they want to get together, they have obstacles, etc.). Gogol completely removes all this, but not only does he not provide a love affair, he parodies it.

Khlestakov shows off in front of the mayor’s wife and daughter, recklessly dragging himself after both. First, he offers Anna Andreevna to retire “under the shade of the streams,” then he asks Anna Andreevna for Marya Antonovna’s hand. This transition happens at lightning speed. Here he falls to his knees out of love for Marya Antonovna, after she accidentally walked into his room. Then Anna Andreevna drives her daughter away, he throws himself on his knees in front of her: “Madam, you see, I am burning with love! I'm in love with you." Then Marya Antonovna runs in with the words "oh, what a passage". Khlestakov grabs her hand: “Anna Andreevna, do not oppose our well-being, bless constant love.” And the mayor, naturally, is amazed: “So you’re into it?..”(Fig. 11).

Rice. 11. Declaration of love. "Inspector" ()

Gogol portrays this parody love affair, using the cliches of their predecessors that were already boring to the audience:

“Khlestakov: You can’t stop me in any way; on the contrary, you can bring pleasure. Dare I be so happy as to offer you a chair? But no, you should not have a chair, but a throne. How I would like, madam, to be your handkerchief to hug your lily neck. My life is in the balance. If you crown my constant love, then I am not worthy of earthly existence. I’ll shoot myself.”

This is all, apparently, from the repertoire of literature contemporary to Gogol. All this is completely absurd, ridiculous. And then Khlestakov leaves, he seems to have already become engaged to Marya Antonovna. The mayor and his wife are euphoric, they are planning to arrange their life in St. Petersburg:

“Governor: Just from some mayor’s wife and suddenly became related to some devil!

...you can get a big rank...

...with time you will become a general. The cavalry will be hung over your shoulder.”

And in the midst of this celebration, the postmaster appears with a printed letter. And then immediately the true auditor.

We cannot fully appreciate this now, but for contemporaries this was unusual. This was the innovation of Gogol the playwright.

Composition "The Inspector General"

You need to understand that the play lives only on stage. Bulgakov (Fig. 12) has a novel called “Notes of a Dead Man” (or “Theatrical Novel”).

Rice. 12. Mikhail Bulgakov ()

There is one wonderful place there. The hero wrote a novel, the novel is not published, only a small piece. He lives alone in a room in communal apartment. Only a cat brightens up his loneliness. On lonely evenings it seems to him that a sacred box is being erected on his table. People begin to walk in this box. They say. Shots are heard somewhere, music is heard somewhere. He immediately liked this game, and every evening he waits when he can imagine it all again. He begins to write down what he sees. And suddenly he realizes that he is writing a play. Of course, one cannot so easily compose a play like Bulgakov, or his hero, or like Gogol. But you can imagine the play on stage. After all, the play exists only on stage. Imagine what it looks like on stage. In order to truly understand the play, you need to imagine yourself as a director, imagine the selection of actors for one or another role, think about how the scene should be designed, what kind of music should accompany the play.

It would seem that there is such a thing that absolutely cannot be conveyed on stage. This is the epigraph to “The Inspector General”:

.

A long time ago, in the 70s, at the Taganka Theater in Moscow there was a performance based on Gogol, it was called “The Revision Tale”. There were fragments of both “Dead Souls” and “The Inspector General”. When the audience went out into the foyer after the performance and received their clothes, they approached the mirror, and this mirror was crooked, like in a funhouse. This - “There’s no point in blaming the mirror if your face is crooked”. This is how the director and artist Yuri Petrovich Lyubimov (Fig. 13) conveyed Gogol’s epigraph.

Rice. 13. Yu.P. Lyubimov ()

The comedy should knit itself together, with its entire mass into one big common knot. The plot should embrace all faces, not just one or two, and touch on what worries more or less all the characters. There is such a plot in “The Inspector General”:

“I invited you, gentlemen, to tell you some very unpleasant news. An auditor is coming to see us.”

And immediately everyone becomes busy. This covers everyone. Just like the denouement, when everyone stands as if struck by thunder (first from the news that Khlestakov is not an auditor, and then from the arrival of the gendarme).

In the first act he says his famous phrase mayor. And immediately: “How’s the auditor? How's the auditor? - officials ask.

In the fifth act:

“Postmaster: The official whom we took for an auditor was not an auditor.

All: Why not an auditor?”

This kind of mirroring occurs many times in the composition of The Inspector General. It is, of course, not at all accidental. First they read Chmykhov’s letter to the mayor, at the end they read Khlestakov’s letter to Tryapichkin. Moreover, the reader learns about the postmaster’s passion for reading other people’s letters in the first act.

The doubling in “The Inspector General” is very interesting: Dobchinsky and Bobchinsky, Anna Andreevna and Marya Antonovna, a mechanic and a non-commissioned officer, two letters, two rats. And how Dobchinsky and Bobchinsky argue at the beginning who was the first to say: "Eh!", so in the end they will argue, blaming each other on who saw Khlestakov as an auditor.

Khlestakov declares his love twice. First to Marya Antonovna, then to Anna Andreevna. He falls to his knees twice, speaks twice about constant love. Several times all the officials pass in front of the readers in a line. First in the first scene with the mayor, then when they appear at Khlestakov’s, then when Khlestakov’s letter to Tryapichkin is read, which characterizes all of them.

There are a lot of echoes in this play. For example, Chmykhov writes:

“You don’t like to miss out on something that just floats into your hands.”

And the non-commissioned officer answers:

“I have no reason to give up my happiness.”

In The Inspector General there are also examples of rude comedy, which already has its source not in character, but in some stage action. For example, the mayor puts on a case instead of a hat, Bobchinsky falls with the door.

The most important thing in the composition of “The Inspector General” is silent scene(Fig. 14).

Gogol demands that the silent scene last for a very long time, an unusually long time. Here's what he writes:

“For almost a minute and a half, the numb group maintains this position.”

The meaning of the ending. In "Theatrical Road Trip" one of the characters will say:

“But, nobleman, they all became silent as the reckoning came.”

This was also discussed in the denouement of The Inspector General. Gogol will say that this is a manifestation of our true conscience.

There are many things in the construction of the play that are not immediately noticeable, but are unusually interesting roll calls, motives, moments. To better understand this play, you need to imagine it on stage.

Khlestakov

This is very important words. Khlestakov (Fig. 15) - in each. Pay attention to an excerpt from N.V.’s letter. Gogol:

“Everyone, at least for a minute, has become or is becoming a Khlestakov... And a clever guards officer will sometimes turn out to be a Khlestakov, and a statesman will sometimes turn out to be a Khlestakov, and our brother, a sinful writer, will sometimes turn out to be a Khlestakov. In short, it’s rare that someone won’t be one at least once in their life.”

Rice. 15. Khlestakov ()

We have already said that Khlestakov is visible in the dreams of the mayor and Anna Andreevna. And Dobchinsky seems to confirm this observation.

In “Theatrical Travel” there are these words:

“The first thing a person does is ask: “Do such people really exist?” But when has a person ever been seen to ask the following question: “Am I really clean from such vices?” Never!"

The moralizing charge of this comedy is expressed not in showing the vices of others, but in making each of us ask ourselves if there is Khlestakov in us. Gogol discussed this topic in a conversation with Sergei Timofeevich Aksakov.

Khlestakov is a completely incomprehensible figure. Grigory Aleksandrovich Gukovsky (Fig. 16) in his book “Gogol’s Realism” says that Khlestakov behaves like a real auditor. Everyone is deceived, because a real auditor would do the same thing: he would accept bribes, he would talk about how he important person, would use this power.

Rice. 16. G.A. Gukovsky ().

Yuri Mikhailovich Lotman (Fig. 17) is interested in how “ small man in Gogol” tries to play a role even an inch higher than the one that was given to him.

Lotman draws attention to the fact that Khlestakov despises himself. This is very easy to prove:

“You'll think I'm just rewriting? No... I just go into the department for a minute, I say it like this, but it’s like that. And then some rat started scribbling away for a letter.”

So the “rat” for writing is him.

Rice. 17. Yu.M. Lotman ()

It is very strange to read how Khlestakov begins with the fact that the head of the department is with him friendly foot. Of course he made it up. And he ends up saying that he goes to the palace every day and that tomorrow he will be promoted to field marshal. At this phrase he switches off, because he had too much breakfast and drank a lot at breakfast. And this doesn’t bother anyone. True, the mayor says:

“Governor: Well, what if at least one half of what he said is true? (Thinks.)

And how could it not be true?

Having taken a walk, a person brings everything out: what’s in his heart, so on his tongue. Of course, I lied a little; and indeed, no speech is made without lying down.”

To understand what Khlestakov’s mystery is, it is interesting to recall some facts about Gogol. Gogol's life is so fantastic that anything can happen in it. Remember how the story “The Nose” ends:

“Whatever you say, such incidents happen in the world - they are rare, but they do happen.”

Khlestakov is absolutely sincere. In the sixth scene of the third act, when he says that he went to the palace, he completely unconsciously invents himself. Even when he was openly caught lying, he overcomes this situation with complete genius:

“Yes, there are two “Yuri Miloslavskys”. One, indeed, belongs to Mr. Zagoskin, but the other is mine.”

To which the mayor said:

“I probably read yours. So well written"(Fig. 18) .

Rice. 18. “Inspector” ()

Khlestakov played by Evgeny Mironov in the 1996 film is very good. Great artists feel the line between the familiar and the unusual, believable and beyond the bounds of plausibility (Fig. 19).

Rice. 19. Screen version of “The Inspector General” ()

There is another interesting technique that distinguishes any comedy and which works well in The Inspector General. This technique is called deaf conversation. More antique comedy started with exactly this: two characters come out who speak the same language, but in different dialects. And in one dialect the word means, for example, some kind of reward, and in another - for example, a chamber pot. This is the misunderstanding that is built on comic effect. In Gogol, this scene is absolutely fantastic - a conversation between Khlestakov and the mayor in a hotel. It would seem that now everything should be explained. The mayor thinks that this is the auditor. Khlestakov thinks that the mayor has come to send him to prison (Fig. 20).

Rice. 20. Khlestakov and the mayor ()

This scene is so good that there are absolutely no seams visible anywhere, everything is very convincing:

“Governor: My duty, as the mayor of this city, is to take care that those passing by and everyone noble people no harassment...

Khlestakov: It’s not my fault... I’ll really pay... They’ll send it to me from the village.

Mayor: Let me invite you to move with me to another apartment.

Khlestakov: No, I don’t want to! I know what it means to go to another apartment: that is, to prison. What right do you have?

The mayor should have understood everything, but he thinks that Khlestakov means that if he moves with him to another apartment, that is, accepts such a service from the mayor, then Khlestakov will be sent to prison for the fact that he is a bad auditor.

“Khlestakov: I’m going to the Saratov province, to my own village.

Mayor: To the Saratov province! A? And she won't blush!

You need to keep your eyes open with him.”

It is on such misunderstandings and roll calls that everything in “The Inspector General” is built.

“Governor: Please look at the bullets he casts! And he dragged in his old father! Nicely tied the knot! He lies, he lies, and he never stops! But what a nondescript, short one, it seems that he would have crushed him with a fingernail. Well, yes, just wait, you’ll let me slip. I’ll make you tell me more!”

This is the comic effect. Khlestakov speaks the truth, but they don’t believe him. Khlestakov is lying, and everyone is ready to believe him.

Very often, when speaking about the “Inspector General”, they use the word grotesque.

Grotesque- bringing the irrationality of life to the point of absurdity.

Let's look at this specific example. Gogol is completely clear that in Russian life a uniform means much more than the dignity of the one who wears it. This is, of course, illogical. This is a rather sad side of Russian life. Gogol seems to be asking himself the question: what if the uniform is put not on a person, but on the nose? Then it turns out that the nose is a general, a state councilor (Fig. 21).

And Major Kovalev, unfortunate, with a flat place instead of a nose, meets his own nose in the Kazan Cathedral and invites him to return to his place. To which the nose answers him: “ Judging by the buttons of your uniform, you and I serve in different departments, dear sir.” This is how Gogol's grotesque works.

And in “The Inspector General” there is such a moment: what if the uniform is only imaginary; But what if this imaginary uniform is attached to a complete nonentity, a dummy? It turns out that everyone is ready to mistake him for an auditor. Commenting on this place, the authors Soviet textbooks they always said that this meant exposing the tsarist bureaucratic system: anyone can look like an auditor, even if he does not pretend to be one.

This combination of absurdities is very comical and very meaningful. The note that the mayor wrote on the tavern bill, which was given to Khlestakov, becomes such a technique:

“I hasten to inform you, my dear, that my condition was very sad, but, trusting in God’s mercy, in two pickled cucumbers especially for half a portion of caviar, a ruble and twenty-five kopecks..."

This is a comic technique when two completely different texts collide and produce a comic effect.

The cause-and-effect relationships in The Inspector General are very strange. Remember the assessor who smells of vodka because his mother was hurt. Teachers are a wonderful subject for Gogol's ridicule. For example, to a history teacher who liked to break chairs, Khlopov notes many times that this should not be done, to which he replies:

« Whatever you want, I won’t spare my life for science.”.

Another teacher makes faces. Mayor says:

“If he did this to his students?.. and then I can’t judge, maybe that’s how it should be.

If he does this to a visitor, God knows what could happen. Mr. Auditor can take this personally.”

For Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, Khlestakov is an auditor, because he looks at their plates, does not travel and does not pay money.

These are just some of the comic techniques. There are also, of course, comic names (like Derzhimorda or Lyapkin-Tyapkin). There are also comic acts. There are many comic techniques. But the question is not to list them, but to see how they work. Gogol has all this in place, which is why he wrote a play that is read and staged to this day.

Bibliography

1. Literature. 8th grade. Textbook at 2 o'clock. Korovina V.Ya. and others - 8th ed. - M.: Education, 2009.

2. Merkin G.S. Literature. 8th grade. Textbook in 2 parts. - 9th ed. - M.: 2013.

3. Kritarova Zh.N. Analysis of works of Russian literature. 8th grade. - 2nd ed., rev. - M.: 2014.

1. Website sobolev.franklang.ru ()

Homework

1. Give examples of “mirage intrigue” in the works of N.V. Gogol.

2. List and explain the principles on which the plot of the play is built.

3. What is the innovation of Gogol the playwright?

The plot of “The Inspector General” is based on a fairly common motif in literature of mistaking a small official for an important person. However, the plot is not the main thing.

Gogol's innovation lies in the fact that he introduced into his comedy whole line elements that make it high social comedy, which focus the viewer’s attention on the fact that the situations and absurdities shown in the comedy are not accidental, they are a natural phenomenon of modern life.

Khlestakov is by no means a conscious rogue who planned to deceive the provincial “donkeys”; he did not intend to declare himself an impostor, but turned out to be one by accident. Moreover, all his further lies and boasting about his life in St. Petersburg are also due to circumstances: officials persistently encourage him to tell utter lies, waiting for him to add something extraordinary about himself. And Khlestakov lies impromptu.

Khlestakov is by no means distinguished by cunning and intelligence. He, according to author's description, “somewhat stupid and, as they say, without a king in his head.” This is especially important to understand ideological meaning comedies. If Khlestakov were smart, cunning man, then one could easily assume that, due to character traits and dishonest motives, he decided to take advantage of the opportunity for personal gain, and therefore the very similar fact would seem exceptional, atypical and would lose its incriminating power.

“The typical confusion of social reality itself,” writes V. Gippius, “would be replaced by its artificial confusion as a result of individual evil will.” In his “Notice” for actors, Gogol emphasized that “the power of general fear” creates a “significant person” out of such a nonentity as Khlestakov.

In the depiction of character images and in the construction of the plot, Gogol avoided generally accepted templates - exceptional events, crimes, etc.

P.A. Vyazemsky noted that the comedy “is not based on any disgusting and criminal action”; there is no “oppression of innocence in favor of strong vice, no selling of justice.”

There is not a single positive hero in The Inspector General, although, as Vyazemsky correctly noted, Gogol does not have “vile heroes.” Gogol doesn't make his own negative heroes exceptional villains. And their very vices are perceived as a natural phenomenon of the vicious as a whole social system. “Sins” that everyone has

officials depicted in comedy are by no means connected with individual psychological qualities their characters. “You don’t like to miss what’s floating in your hands,” says the mayor. The following episodes involving bribes are very typical in this regard.

Khlestakov becomes a bribe-taker, like an auditor, due to a combination of circumstances, while his bribes are not at all connected with any oppression; at first they even take on an innocent form - “the favor is reciprocal,” politely offered by the mayor (Act 11).

Then Khlestakov entered into the role, and the “reciprocal favor” turns into blatant extortion (Act IV). At the same time, the latter does not offend “suffering persons”, because it is thought of as “in the order of things.” If Gogol had featured positive heroes in a comedy, contrasted with bribe-takers and swindlers, exposing them, the comedy would have lost its deep generalizing social meaning, and its accusatory pathos would have turned into a moral and edifying maxim, boiling down to the fact that it is wrong to take bribes and oppress people etc.

Gogol managed to avoid this by abandoning the positive type, which further enhanced the sharpness of his satire, focusing the viewer’s attention on “everything bad in Russia.” Gogol himself later explained that the only positive hero his comedies are “laughter, merciless and evil, it carries out judgment on the characters.”

The close-knit camp of officials is contrasted with “citizenship,” which is introduced only occasionally in the comedy. Gogol undoubtedly has sympathy for these defenseless people suffering from tyranny. We know about them as the passive object of arbitrariness and extortion of the Skvoznikov-Dmukhanovskys, Lyapkinykh-Tyapkinykh, Derzhimord and other government officials.

This is a non-commissioned officer's widow, flogged by order of the mayor for no reason, for the order is such that Derzhimorda “puts lanterns on everyone - the right and the wrong”; this is a locksmith whose husband the mayor “made into a soldier” only because he did not receive a bribe from him; these are, finally, all those who came to Khlestakov to ask for protection from the arbitrariness of the mayor and officials, whose voice is heard behind the stage and “hands stick out of the window, with requests,” and also in the future appear in the doorway after some figure “in a frieze overcoat, with an unshaven beard, a swollen lip and a bandaged cheek,” the petitioners themselves.

The merchants depicted in the comedy, despite the fact that they also suffer from the mayor’s extortions, are not among those with whom the writer sympathizes. They are presented in a clearly ironic manner. Gogol understood perfectly well that in their hands there was money that was capable of taming any rage of the “derzhimorords”, that the merchants themselves were making money at the expense of ordinary people.

The heroes of Gogol's comedy are complete characters, living people, not masks. At the same time, they are shown in the aspect of popular perception of their actions and deeds. Therefore, there was no need for the writer to read lectures about the dangers of bribes or about the impermissibility of assault practiced by the Derzhimords, this is clear and without moralizing maxims. The writer, with the entire content of the comedy, expresses his indignation towards all forms of despotism, bureaucracy, bribery, embezzlement, etc.

Gogol's goal was to “cut off evil at the root, not at the branches.” Therefore, comedy is not perceived as a criticism of official abuses or vices individuals, but as a satirical denunciation of the entire social system, its “disease” as a whole.