King of Botswana. History of Botswana

Ruth and Seretse Khama, Bechuanaland, 1950Imagine for a moment that you are in love and preparing for a wedding, despite the obvious disapproval of your parents on both sides. You love each other and the rest seems insignificant to you. And then the British Prime Minister appears on your doorstep and declares that you must give up your love, otherwise your wedding will lead to an international political crisis. Sounds absurd, right? But what seems absurd now was a harsh reality back in 1948, because the bride was a white middle-class Englishwoman and the groom was a black prince from the British protectorate of Bechuanaland, now known as Botswana.

They met in England in 1947. He is the 26-year-old future king of one of the forgotten countries of South Africa, she is the 23-year-old daughter of a retired British military man. The fate of the future lovers, without knowing it, was determined by Muriel Williams-Sanderson, Ruth's sister, with whom they were very friendly. Muriel offered to accompany her on dance party, organized for military families by the London Missionary Society. By coincidence, Seretse, the pitcher, also ended up there. big hopes, a superbly educated Oxford student, a member of the ancient African family of Bamangwato and crown prince of Bechuanaland. In addition to the royal title, Seretse Khana had a remarkable mind and very advanced views on modernity, the political system and, most importantly, his own country. Seretse dreamed of the independence and freedom of his state, which was under British protectorate and was, in fact, deprived of the opportunity to develop both economically and politically.

Everything was decided by a dance to which, despite prejudice, a black student dared to invite a white lady. And from that moment on, both of their worlds turned upside down. The love of Ruth and Seretse, which arose spontaneously, like a hurricane in the steppe arises without any warning, became the same “at first sight.” Their romance developed rapidly, and within a year they realized that they had to get married. Despite the protests of their relatives, the young people decided that they were ready to go against the will of their families: separation seemed to both of them to be a disaster. But they had no idea what a disaster their marriage would be for Great Britain and its plans for the reconstruction of Africa.

So that we, from the bell tower of 2016, understand the full depth of what is happening around lovers political conflict, we need to remember that just at that time in South Africa (then South Africa), neighboring Botswana, the Afrikaner National Party was gaining popularity, preaching the ideas of racial segregation in its most extreme manifestations. In Africa, it was already not too smooth with “democracy” in relation to blacks, but extreme nationalists believed that the ruling party in South Africa was not doing enough to maintain the purity of the white nation. And the 1948 elections were looming...

And against this political background, information appeared in the press about a romance between a dark-skinned prince and a white Englishwoman. The current South African government has made it clear to its British counterparts that this alliance could have dire consequences for the relations of both countries. If Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams get married, this will give extra trump cards to apartheid supporters in the upcoming elections, which, of course, neither Great Britain nor the ruling elite of South Africa were interested in. It’s even surprising how neither side took extreme measures in this regard...

Everyone tried to dissuade Ruth. But if the father and sister simply did not like the idea of becoming related to a black guy, then the British Secretary of State for the Commonwealth brought other ideas to the girl, political arguments. In fact, the girl was told that if she did not give up her African husband, it could be the beginning of the end of the British Empire in Africa.

Seretse Khama's situation was no better: his uncle, who was temporarily acting as regent, gave his nephew a real dressing down. Not then young man sent to study at Oxford so that he could disgrace his family by getting involved with a white man: in his homeland, Seretse was waiting not only for the throne, but also for the “right” bride - a girl from his own tribe. It is noteworthy that the tribe itself reacted to the news of the white love of their future king much more favorably than their own uncle. But he had his own plans for the throne, and the scandal surrounding his nephew came in handy. If William Shakespeare were alive, this story might become a new source of inspiration for him.

And yet, Seretse and Ruth set a wedding day. However, the wedding never took place: shortly before the ceremony, someone intimidated the priest who was supposed to marry a black groom and a white bride. Realizing that they had nowhere to wait for blessings and help, the lovers secretly got married in 1948, a year after their fatal acquaintance, in an ordinary registry office.

The news leaked to the press about the marriage of an African prince and a white lady had the effect of a bomb. The Prime Minister of South Africa declared this union “sickening” to the whole world, violating moral interracial laws. Angry telegrams poured in from Pretoria to the British government, condemning the marriage of an Englishwoman and an “African.” And is it any wonder that the National Party, which received the majority of votes in the elections to South Africa, first adopted a law banning interracial marriages (1949), and at the second stage introduced an amendment to the Morality Law, which established criminal liability for sexual contacts white man with a representative of a different race. Relations between Great Britain and South Africa were cracking at the seams; plans for the possible annexation of Bechuanaland to its southern neighbor were completely dashed.

In 1949, Seretse and a pregnant Ruth arrived in Bechuanaland, believing that the fuss about them had died down. And in vain. Khama's native tribe, instigated by Uncle Tshekedi, who had his own plans for the throne, refused to recognize the white Englishwoman as their queen. Seretse was required to renounce either his wife, whose marriage was not sanctioned by the elders, or his claims to the throne. From a purely political position, it was beneficial for many to remove this inconvenient pair from sight, the mere sight of which acted on the white population of Africa like a red rag on a bull. The British government intervened in the conflict. In March 1950, Seretse was summoned to London, ostensibly to meet with the Commonwealth Affairs Committee regarding the settlement of issues affecting him. interracial marriage. It was a trap.

English politicians, in collusion with the king's uncle, tried to force Khama to renounce his claims to rule the country, but were met with refusal. As punishment for Seretse's obstinacy, Khama became a prisoner of the British government, and together with Ruth, they could not leave Great Britain until 1956, let alone return to Seretse's homeland. This was the payback for their interracial love.

But it’s not Khama’s character to give up. Loyalty to his love was not the only virtue of the young king. He had charisma, was full of real ideas on how to change life in his country for the better, and was least likely to give up under the pressure of circumstances. This attracted his compatriots to him. If Seretse could not become king of Bechuanaland, then he had to become its president. During his years of living in exile, he prepared good ground for this.

In 1956, the elders of the Bamangwato tribe sent a formal demand to Elizabeth II to release their leader from the country. The current political situation at that time no longer suggested refusal, and Khama, along with his white wife and two children, returned to his homeland. Then events developed rapidly.

Khama renounced his claims to the throne, which led to the abolition of the monarchy in the country. A year later, he joined the governing council of Bechuanaland, in 1961 he created the Democratic Party of Botswana, which after 4 years won parliamentary elections and in 1966 Seretse Khama was elected president of the land in which he was not allowed to become king. He went down in the history of Botswana as the man who managed to transform it from one of the poorest countries in Africa into one of the most rapidly developing countries on the continent. All this time, Ruth was next to her husband. In trouble and in joy, relentlessly, faithfully, and without thinking of another, simple fate for yourself. White-skinned Ruth Wilson Khama became the most influential and politically active First Lady of Botswana.

And in the fall of 2016, just in time for the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of Botswana's first president, Amma Asante's film A United Kingdom, based on this incredible story, was released. romantic story Seretse Khan and Ruth Williams. The roles of lovers who not only overcame a lot of obstacles on the path to happiness, but also changed political system actors Rosamund Pike and David Oyelowo performed their country.

Photo source: Getty Images, film stills

STORY

Hunters and gatherers who spoke Khoisan languages were the first to come to what is now Botswana. For example, the earliest settlements at a site in the Tsodilo Hills (northwest of the country) date back to around the 15th century. III century BC e. In the last few centuries BC. e. Some tribes began to turn to livestock farming, using the relatively fertile lands around the Okavango Delta and Lake Makhadikhadi. The pottery of the Bambata culture dates back to the 3rd century - probably Hottentot in ethnicity.

At the beginning of our era, Bantu farmers came to South Africa, and with their arrival began iron age. The first Iron Age sites in Botswana date back to around 1190 AD. e. and are probably related to the Bantu peoples of the Limpopo Valley. By 420 AD e. include the remains of small beehive-like houses at a settlement near Molepolole (almost identical to finds at a site near Pretoria); there are similar finds from the 6th century in the north-west, in the Tsodilo hills.

In the 12th century, the spread of the Moritsane culture, associated with the southeast of Botswana, began: its carriers were tribes of the Sotho-Tswana group, who, although they belonged to the Bantu peoples, were engaged in animal breeding rather than agriculture. From a material point of view, this culture also combined features of older Upper Neolithic cultures (like Bambat) and the Bantu culture of the eastern Transvaal (Leidenberg culture). The spread of the Moritsane culture is associated with the growing influence of the Khalahadi chiefdoms.

In the east and center of the country, the leaders of Toutswe had great influence, conducting active trade with the eastern coast. This entity later fell under the rule of the Mapungubwe state and later the rulers of Greater Zimbabwe.

Around the 9th century, other Bantu tribes, the ancestors of the current Yeyi and Mbukushu, began to penetrate into the north-west of the country.

In the 13th century, the Sotho and Tswana leaders in the Western Transvaal began to gain strength. The leaders of the Rolong tribe began to put serious pressure on the Khalahadi tribes, forcing them to either submit or move further into the Kalahari. By the mid-17th century, the Rolong-Khalahadi chiefs controlled lands as far as what is now Namibia, and news of their conflicts with the Hottentots over copper mines even reached Dutch settlers in the Cape Colony.

TO XVI century refers to the separation of the Tswana proper under the rule of the Hurutshe, Kwena and Kgatla dynasties, who founded the kingdom of Ngwaketse at the end of the 17th century, subjugating the Khalahadi and Rolong. They soon had to face external threats: first they were attacked by tribes fleeing European influence in the southwest, and later the Tswana had to deal with the consequences of Mfekane. In 1826, the Tswana clashed with the Kololo, who killed the leader Makabu II. The Tswana managed to drive the Kololo further north, where they settled briefly. The Kololo reached in the west as far as present-day Namibia (where they were defeated by the Herero), and in the north - as far as the Lozi lands in the upper Zambezi.

After the end of the Mfecane wars, Tswana chiefs began to strengthen their influence in the region, acting as trade intermediaries between the Europeans in the south and the northern tribes. Especially notable were Sechele, the ruler of the Kwena who lived around Molepolole and Kama III, the king of the Ngwato, who owned virtually all of modern Botswana. Kama was an ally of the British, who used his lands to bypass the hostile Boer republics (Transvaal and Orange Free State) and the Shona and Ndebele kingdoms. Tensions grew in the region, and in 1885 the Tswana chiefs Kama, Batwen and Sebele petitioned the British Crown for protection. On March 31, 1885, a British protectorate was proclaimed over the Tswana lands, called Bechuanaland. The northern part of Bechuanaland remained under the control of the English crown, and Bechuanaland was included in the Cape Colony (now part of South Africa; which is why most Tswana speakers now live in South Africa).

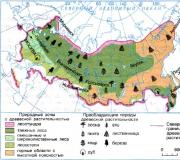

German map of South Africa 1905. Bechuanaland has not yet been divided into northern (protectorate) and southern parts. The British initially assumed that Bechuanaland, like Basutoland (Lesotho) and Swaziland, would be included in Rhodesia or the Union of South Africa, and therefore even Mafikeng, located in the Cape, became the administrative center of the protectorate colonies. Special programs the development of Bechuanaland was not envisaged; moreover, they provoked a sharp protest from the Tswana leaders, who did not want increased European influence on their lands. The inclusion of the protectorates in South Africa was constantly postponed, and in the end, when the National Party began to introduce an apartheid regime in the country, it was decided not to merge these territories into one. A joint advisory council was created in 1951, and a constitution was adopted in 1961, which provided for the creation of a legislative assembly with advisory voting rights.

Great Britain did not want to change its political system until it was convinced that the country could independently develop its economy. In 1964, the colonial administration agreed to the possibility of declaring independence, in 1965 self-government was introduced, and the capital was moved from Mafikeng to the quickly rebuilt Gaborone, and in 1966 the independent Republic of Botswana was proclaimed. The first prime minister was Seretse Kama, one of the leaders of the liberation movement and a legitimate contender for the throne of the Ngwato leader. He was re-elected twice more and died in 1980 while serving as president.

The economy of independent Botswana was based on exports (in particular, diamond deposits were found in the country); In order to get the maximum benefit from these exports, in 1969 the government achieved changes in the terms of the customs agreement with South Africa.

After Kama, Vice President Ketumile Masire became president, and was also re-elected twice later. Masire resigned in 1998, and Festus Mohae became the leader of Botswana.

This story begins in 1947 at a ball organized by the London Missionary Society, where Ruth Williams, who worked as a typist in the London insurance branch of Lloyd's Bank, met Seretse Khama, a law student studying law at Oxford. Ruth was 24 years old, Seretse - 26.

Seretse Khama (Seretse Goitsebeng Maphiri Khama) was born in 1921 in Bechuanaland (now Botswana), then a British protectorate. He was the son of King Sekgoma Khama II and his wife Queen Tebogo, and the grandson of King Khama III.

Seretse Khama

The child received the name Seretse, which means “clay that binds,” in honor of the reconciliation between his father and grandfather, as a result of which his father ascended to the throne. But the father ruled for only two years and died. Four-year-old Seretse was proclaimed king, but since he was still small, his uncle, his father's brother, Tshekedi Khama, acted as guardian and regent. The uncle ruled the country at his own discretion, sending his nephew away to study. By sending his nephew to London, his uncle believed that he had gotten rid of his claims to the throne for a long time. But my uncle was wrong. In London, Seretse met Ruth, and this meeting changed life not only in Bechuanaland, but also had an impact on race relations in Britain and throughout the world.

Ruth Williams was born in 1923 in South London to George and Dorothy Williams. George Williams was a captain in the British Army, served in India, and after his retirement was involved in the tea trade. Ruth had a sister, Muriel, with whom she was friends all her life.

Ruth attended Eltham Grammar School, but when the Second World War began World War went to work as an ambulance driver at various airfields in southern England. After the war, Ruth got a job in the insurance department of Lloyd's Bank as a secretary-typist.

Ruth Williams

She and Seretse were brought together by love for jazz music. Seretse, like Ruth, liked the band The Ink Spots. They had a good time together, and after a year they realized that they loved each other and wanted to get married.

At that time, mixed couples were very rare and caused rejection in society. When Ruth told her father that she wanted to marry a black guy, her father disowned her and kicked her out of the house. Until the end of his days, Ruth’s father never came to terms with the fact that his daughter married a black man, even a king. The employer also immediately fired Ruth as soon as he learned about her future marriage to a black man.

Seretse wrote to his uncle and asked the missionary society to help them, but the uncle replied that he would “fight him to the death if he brought a white wife,” and the missionary society could not help because the elders of the tribe in Bechuanaland could not accept the fact that that the "mother of the nation" will become white woman. The Anglican Church also could not allow the marriage of a white woman with a black woman. Under pressure from the church, the government banned young people from getting married in church. But this did not stop either Ruth or King Seretse. They registered their union in the registry office.

The already legal spouses went to Bechuanaland at the request of their uncle. Seretse's uncle, Tshekedi Khama, tried to have his nephew's marriage to an Englishwoman annulled, but Seretse was a king, not an impostor like his uncle, and at a public meeting of the tribe, the majority sided with him.

But such a mutiny on a ship in a neighboring country did not please the racist party of South Africa, which was then in power, and under their pressure, the British government began an investigation into Seretse’s suitability to rule the protectorate. Finding that Seretse was more than qualified to rule Bechuanaland, the report was shelved and Seretse and his wife were told to return to London until better times, essentially sending the king into exile. Great Britain did not want to quarrel with South Africa for fear of losing cheap supplies of gold and uranium.

Ruth's home was closed to her and her husband. In addition, Ruth was not hired anywhere. Among ordinary people, racial prejudices generally still prevailed. It was impossible to go to the husband’s homeland, and in the wife’s homeland the couple was looked upon as outcasts.

It seemed that the uncle should have celebrated the victory, but times were quickly changing. In Britain itself, protests began against British racism, and in Bechuanaland, when they tried to replace King Seretse Khama, the people refused to comply.

In 1956, Seretse and Ruth were allowed to return to Bechuanaland after Seretse abdicated the throne.

Returning to their homeland, Sereste and Ruth tried to raise cattle on the ranch, but they had no experience in this matter, and this idea failed.

Then Seretse decided to return to politics. He was first elected to the tribal council, and then, in 1961, Seretse created the Bechuanaland Democratic Party. The exile's aura attracted large numbers of voters to Seretse's banner, and he won the elections in 1965. Seretse proclaimed a course for complete independence from Great Britain and the creation of a country called Botswana with its capital in the city of Gaborone. In 1966, Botswana gained independence, Seretse Khama became its first president, and Queen Elizabeth II awarded him the Order of the British Empire. Seretse Khama becomes Sir and Ruth becomes Lady Khama.

President of Botswana Seretse Khama, Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain, Lady Ruth Khama and Princess Anne

At the time of the formation of the republic, Botswana was the third poorest country in the world. The country had only 12 km of paved roads, there was practically no infrastructure, and the population was completely illiterate. Seretse created the country's economic program from scratch. He placed his main emphasis on copper and diamond mining and beef production. He took serious measures to combat corruption, introduced low and stable taxes for mining companies and a low percentage of income taxes, proclaimed freedom of trade and the individual, and the rule of law. Khama tried to attract foreign investment to the country for development Agriculture, industry and tourism.

These and several other transformations of Seretse have turned Botswana's economy into one of the fastest growing in the world. The government invested all revenues in the development of the country's infrastructure, healthcare and education, which further stimulated economic development. It can be said that Seretse Khan's reign was the "golden age" of Botswana.

Monument to the first President of Botswana Seretse Kham in front of the Botswana Parliament building

Botswana Airport is also named after Seretse Khama.

In addition, Khama created a small but professional army, which successfully defended the country from incursions by armed groups from South Africa and Rhodesia. Prevented Khama and militant groups from operating inside Botswana. In foreign policy Khama was careful enough to guarantee his neighbors immediately after independence that Botswana would not attack anyone. It was Khama who played a key role in negotiations to end civil war in Rhodesia and in the independence of Zimbabwe.

Khama introduced in Botswana national currency, pula (translated as "rain". Botswana has little rain, so it is highly valued), before this the South African rand was in use.

All this time, Seretse had his beloved wife Ruth by his side. She did not like social gatherings, but was an active and influential first lady in political life countries. Seretse treated his wife with great respect.

Ruth remained faithful to English traditions all her life. Wore neat blouses and skirts in an old-fashioned english style, and on Sundays she organized tea parties for the whole family.

The couple had four children: daughter Jacqueline, son Ian and twins Anthony and Tshekedi. Ian Khama became the fourth President of Botswana in 2008. Tshekedi is also a prominent politician.

Seretse Khama suffered from heart and kidney disease. He had diabetes. In 1980, Seretse was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer in London. The cancer was inoperable and Seretse returned home. He died that same year at the age of 59.

After the death of her husband, Ruth remained to live in Botswana and it was then that she received recognition from the citizens of Botswana. She was hailed as "Mohumagadi Mma Kgosi" (queen mother).

Ruth and Seretse's granddaughter, Tahlia, says that her grandmother constantly talked about her grandfather, it was as if he was part of them Everyday life. Her growing up was spent under the shadow of her grandmother's memories of her grandfather, whom she always spoke about with love.

The grandmother herself, according to Takhlia’s recollections, was always elegantly dressed and impeccably combed. She never inserted into her English speech local words, her English remained impeccable, and she always corrected her grandchildren's English.

Ruth with her granddaughter Tahlia

Lady Ruth Khama died in 2002 at the age of 78. She was buried in Botswana next to her husband.

Takhlia says she feels like her grandmother left her special glasses that, like a navigator, guide her through life and help her solve personal problems. Tahlia admires her grandparents' relationship and wants to go through life as resilient and proud as they were. Tahlia is Ruth's only granddaughter, and she hopes not to disgrace her grandmother's memory.

Tahlia Khama is studying fashion in Johannesburg. She has the royal blood of her grandfather and the blood of her grandmother, an ordinary English girl.

In September 1895, the ocean liner Tantallon Castle arrived at the port of Plymouth on south coast England. Three African chiefs, Khama of Ngwato, Batoen of Ngwaketse and Sebele of Kwena, disembarked and at 8:10 a.m. boarded an express train to Paddington Station in London. Three chiefs came to Britain with a special mission: to save their domains - Ngwato, Ngwaketse and Kwenu - and five other tribal territories of the Tswana people (a people in southern Africa, living mainly in what is now Botswana) from Cecil Rhodes. All eight of these Tswana "kingdoms" made up Bechuanaland, which received the name Botswana after independence in 1966.

The Tswana people dealt with Europeans throughout most of the 19th century. In the 1840s, the famous Scottish missionary David Livingstone visited Bechuanaland several times and converted the local king, Sechele, to Christianity. The first translation of the Bible into an African language was made into Setswana, the language of the Tswana people. In 1885, Britain declared Bechuanaland a protectorate. The Tswana were happy with this turn of events because they thought it would protect them from further European expansion, especially from the Boers, with whom they had been in constant conflict since 1835, with the start of the Great Trek into the interior of South Africa. thousands of Boers, in turn fleeing British colonialism. The British also wanted to control the region to stop further Boer expansion, but considered full-scale colonization impractical. High Commissioner Rey in 1885 formulated the British government's position as follows:

“We have no interest in the lands north of Molope [Bechuanaland Protectorate], apart from the need to build a road into the interior. We could limit ourselves for the present to preventing this part of the Protectorate from being taken over by various adventurers or foreign powers, by taking only minimal measures to govern and populate these areas."

However, the situation changed for the Tswana in 1889, when Cecil Rhodes's British South Africa Company began expanding northwards from South Africa, capturing huge chunks of land that would become Northern and Southern Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe). By 1895, when the three chiefs arrived in London, Rhodes also had his eye on the territory southwest of Rhodesia, that is, Bechuanaland. The leaders understood that if these lands fell under the control of Rhodes, they would be devastated and their people would be brutally exploited. The Tswana could not defeat Rhodes by force of arms, but they were going to oppose him by any means possible. They decided to choose the lesser of two evils: greater control by the British government rather than the annexation of Tswana lands by the Rhodes Company. With the help of the London Missionary Society, the chiefs arrived in London to try to persuade Queen Victoria and Joseph Chamberlain, then Colonial Secretary, to tighten control over Bechuanaland and protect them from Rhodes.

On September 11, 1895, the leaders met with Chamberlain for the first time. Sebele spoke first, then Batoen took the floor, and finally Hama. Chamberlain announced that he believed it necessary to establish British control in the region to protect the tribes from Rhodes. The leaders were sent on a tour of England to consolidate public opinion in support of their request. They visited Windsor and Reading near London and made speeches there; they visited Southampton on the south coast, Leicester and Birmingham, which had traditionally supported Chamberlain. They traveled north to industrial Yorkshire, to Sheffield and Leeds, Halifax and Bradford. They traveled west to Bristol and on to Manchester and Liverpool.

Meanwhile, in South Africa, Cecil Rhodes was preparing for what would later be called the Jameson Raid - an armed raid on the Boer Republic of Transvaal, contrary to Chamberlain's strict prohibition. These events apparently made Chamberlain even more sympathetic to the troubles of the leaders. On November 6, they met him again in London. The conversation through an interpreter went as follows:

Chamberlain: I will talk about the lands of the chiefs, and about the railway, and about the laws that must be observed in the territories subject to the chiefs... Now let's look at the map... We will take for ourselves the land necessary for the railway, and nothing more.

Hama: I say that if Mr. Chamberlain wants to take this land himself, I will be happy about it.

Chamberlain: Tell him that I will build the railway myself, using the eyes of the one I send there, that I will take only as much land as it takes, and that I will pay compensation for all the valuables that I need will receive.

Hama: I would like to understand where it will take place Railway. Chamberlain: It will go through his territory, but it will be fenced in, and we won't take any land.

Hama: As for me, I trust that you will do so and that you will deal fairly with me in this matter.

Chamberlain: I will look out for your interests.

The next day, Edward Fairfield of the Colonial Office explained Chamberlain's colonial plan in more detail:

“Each of the three chiefs, Khama, Sebele and Batoen, retains the land on which they live, as before, under the protection of Her Majesty. The Queen will appoint a representative to them, who will live there. The leaders must govern their people in the same way as they do at present.”

Rhodes's reaction to being beaten by three African chiefs was predictable. He sent a telegram to one of his employees, where he wrote: “I am not a whipping boy for these three hypocritical savages.”

In fact, the Chiefs had something valuable that needed protection from Rhodes. And they hoped to preserve this something through the indirect rule of the British. The fact is that by the beginning of the 19th century, the sprouts of political institutions arose in the Tswana states. These institutions were characterized by an unusual level of centralization by the standards of Black Africa, as well as special procedures for collective decision-making, which can be considered as an emerging primitive form of pluralism. Just as the Magna Carta at one time opened the way for the English barons to participate in the political decision-making process and imposed some restrictions on the actions of the English monarchs, so the Tswana political institutions, especially the kgotla, also provided for widespread participation in political process and restrictions on the power of leaders. The South African-born British anthropologist Isaac Schapera (1905–2003) described the function of the kgotla as follows:

“All questions of tribal politics are ultimately decided before a general meeting of all adult men at the kgotla (place of councils) of the chief. Such meetings occur frequently... among the topics discussed... tribal disputes, quarrels between the chief and his relatives, the introduction of new taxes, the organization of new public works, the promulgation of new decrees of the chief...

Disagreement with the leader's opinion is not something out of the ordinary here. Since everyone can speak, these meetings allow the chief to hear the opinions of everyone present and give him the opportunity to listen to all complaints. If the situation calls for it, he and his advisers can be given a harsh scolding, since people are not afraid to speak openly and honestly at these meetings.”

Another limiting factor was the fact that the position of chief among the Tswana was not hereditary, but open to any person who showed sufficient talent and ability for this. Anthropologist John Comaroff has studied in detail political history another Tswana tribal unit called Rolong and concluded that, although in theory the Tswana had clear rules for succession to supreme power, in practice these rules could be applied in such a way as to preserve the possibility of removing bad rulers from power and allowing a talented candidate to become chief. According to the anthropologist, the assumption of the position of leader was determined by the personal qualities of the candidate, but in hindsight his election was explained as if he was the rightful heir. This is reflected in the Tswana proverb: kgosi ke kgosi ka morafe, that is, “a king becomes king only by the grace of the people.”

Returning from England, the Tswana chiefs continued their attempts to secure the independence of their people with the help of the British and preserve their ancestral institutions. They agreed to the construction of a railway in Bechuanaland, but limited British interference in other areas of their economic and political life. They were well aware that the construction of the railway, like all other British activities, would not bring prosperity to Bechuanaland while it was under colonial rule. The story of Quetta Masire, the future president of independent Botswana from 1980–1998, clearly shows what they meant. In the 1950s, Masire was an enterprising farmer who introduced new methods of sorghum cultivation. He found a potential client, Vryburg Milling, which was based overseas in Freiburg, South Africa. Going to the master of the Lobatse railway station in Bechuanaland, Masire asked for two carriages to send his harvest to Freiburg. The station manager refused. Then Masire asked his white friend to join the case. The station manager reluctantly agreed, but asked Masire for a price four times higher than he had asked for from the whites. Masire gave up and came to the following conclusion: “It is the everyday behavior of whites, and not any laws that would prevent Africans from freely owning land or obtaining permission to trade, that will prevent blacks from developing their own businesses in Bechuanaland.”

However, in 1895 both the Tswana chiefs and their people were happy. Perhaps, against all odds, they were able to ruin Rhodes' plans. Since Bechuanaland was still on the margins of British politics, the establishment of indirect rule did not create the type of vicious circle that had developed in Sierra Leone. The Tswana also managed to avoid the consequences of colonial expansion, such as that which was in full swing in the interior of South Africa, which turned the land there into a source of cheap labor for white mine and farm owners.

The initial stage of the colonization process is always a turning point for most societies, a critical period when events occur that will have important and lasting consequences for their economic and political development.

In most societies in sub-Saharan Africa (as well as in South America and South Asia), extractive institutions were established or strengthened during colonization. But the Tswana were able to avoid the establishment of a regime of complete indirect rule, and, what would have been even worse, the seizure of their lands by Rhodes. But it wasn't blind luck. The reason again turned out to be how the existing institutions created by the Tswana people interacted with the inflection point that emerged as a result of colonization. The three chiefs were able to take the initiative to go to London because they had unusually high political authority compared to other tribal leaders in Black Africa. They enjoyed this high degree of authority and legitimacy due to a certain degree of pluralism in Tswana tribal institutions.

Another inflection point at the end of the colonial period can be considered central to Botswana's success in developing inclusive institutions in that country. By 1966, when Bechuanaland gained independence and became Botswana, the great journey of the Sebele, Batoena and Khama chiefs had become a fact of the distant past. In the years since, the British have invested little in Bechuanaland. At the time of independence, Botswana was one of the poorest countries in the world. In the entire country there were a total of 12 kilometers of paved roads, 22 people with a university education, and about a hundred people with a secondary education. It was also surrounded on all sides by white-ruled countries - South Africa, Namibia and Rhodesia - and these countries were hostile to the young African states led by black Africans. Few would include Botswana on a list of countries from which to expect economic success. And yet, over the next 45 years, it became one of the most dynamically developing countries in the world. Today Botswana has the highest per capita income of any country in sub-Saharan Africa - on the same level as successful Eastern European states such as Estonia or Hungary, and prosperous Central American countries such as Costa Rica.

How did Botswana break the mold? The answer is obvious - by quickly building inclusive political and economic institutions after independence. Since that time, the country has been developing democratically, there are regular elections on a competitive basis, and there have been no civil wars or interventions by foreign countries in the history of Botswana. The government strengthens economic institutions based on private property rights, ensures macroeconomic stability, and encourages the development of an inclusive market economy. But of course, the most interesting question is how did Botswana manage to achieve a stable democratic regime, pluralistic political and inclusive economic institutions, while in other African countries the situation was exactly the opposite? To answer this question, we need to understand how a critical turning point (in our case, the end of colonial rule) affected the institutions that existed in Botswana at that time.

In much of sub-Saharan Africa - Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe, for example - independence resulted in missed opportunities and was accompanied by the re-establishment of the same type of extractive institutions that had existed during the colonial period. But in Botswana the first years of independence were very different - again, mainly because historical background, created by Tswana traditional institutions. During this period, many parallels can be seen in the development of Botswana with the development of England after the Glorious Revolution.

The English state had already achieved a high degree of political centralization by the time of the Glorious Revolution (even during the Tudor era), but England had the Magna Carta and parliamentary traditions, and all this could to a certain extent limit monarchs and guarantee a certain degree of pluralism. Botswana was also highly centralized, and relatively pluralistic tribal institutions survived the fall of colonialism.

In England, a new broad coalition had long been formed, consisting of merchants involved in the Atlantic trade, industrialists and minor nobles engaged in trade, and this coalition advocated the strengthening of property rights. Botswana also had a coalition that needed reliable procedural rules: these were the Tswana chiefs, as well as the country's economic elite, which owned the main local wealth - cattle. Although most Tswana land was still communally owned, livestock was private property, and cattle owners had an interest in ensuring that property rights were well protected.

All this, of course, does not negate the fact that history does not know predetermination. Its course could have gone very differently both in England (if parliamentary leaders and new monarchs had tried to use the Glorious Revolution to usurp power) and in Botswana, especially if it had not been so lucky with the leaders Seretse Khama and Quett Masire, who decided to fight for power through fair elections, unlike many post-colonial leaders of Black Africa.

The Tswana came to independence with long history the development of institutions that limit the power of leaders and ensure a certain dependence of the latter on the opinion of the people. Of course, the Tswana people were not unique in this (even within Africa), but they were the only people who managed to maintain such institutions throughout the entire colonial period. The British administration was practically absent here. Bechuanaland was governed from the city of Mafeking in South Africa, and it was only during the British handover in the 1960s that the capital was moved to Gaborone. Moreover, the new capital and the newly established administrative structures did not mean the abolition of local institutions, but were, as it were, attached to them - for example, during the construction of Gaborone, new kgotla were planned there.

Gaining independence also happened in a relatively orderly manner. The independence movement was led by Democratic Party of Botswana (BBO), founded in 1960 by Quett Masire and Seretse Khama. Khama was the grandson of King Khama III and his name Seretse meant "binder clay". As it turned out, it suited him very well. Khama was the hereditary chief of the Ngwato tribe and the most influential member of the Tswana elite in the Botswana Democratic Party.

There was no sales department in the country, since the British were not too interested in this colony. The DPB established a similar body in 1967, calling it the Botswana Meat Commission, but rather than simply taking resources away from ranchers and livestock owners, the commission actually played a central role in the development of the local cattle and beef industry. The commission established barriers between pastures to curb the spread of foot-and-mouth disease and also organized exports - both of which worked to develop the country economically and create the basis for inclusive economic institutions.

Although Botswana's economic growth was initially dependent on meat exports, this suddenly changed when diamonds were discovered in the country. Control natural resources in Botswana was also different from what we saw in other African countries. During the colonial period, Tswana chiefs tried to prevent mineral exploration in Bechuanaland because they realized that if Europeans found valuable metals or gems, then the autonomy of their people will come to an end. The first large diamond was discovered in Ngwato land, Seretse Khama's homeland. Before the discovery was publicly announced, Hama initiated the adoption of a new law, according to which all the mineral resources of the country now belonged to the entire nation, and not to a separate tribe. This ensured that diamond revenues would not increase wealth inequality in Botswana. This also gave new impetus to the process of centralization of the country, since now the “diamond money” could be used to create an effective bureaucracy and infrastructure and invest in education. In Sierra Leone and many other countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, diamonds served only as fuel for conflicts between various groups population and civil wars and rightly earned the nickname “blood diamonds”. In Botswana, the proceeds from the diamond mining industry were used for the benefit of the entire nation.

Changes in legislation concerning national mineral resources were not the only policy measures taken by the Seretse Khama government to strengthen the state. Thus, the Chieftaincy Act (1965), passed by the legislature before independence, and the Chieftaincy Supplementary Act (1970) continued the process of centralization and established the priority of state power and the elected president, depriving chiefs of the authority to distribute land and giving the president the right to the need to remove leaders. Another area of political centralization was measures to further unify the country, for example laws that teaching in schools should be in only two languages - Setswana and English. Today Botswana is a homogeneous country without the ethnic and linguistic fragmentation that characterizes many other countries in Africa - this is precisely the result of language policies: the use of only two languages in school has minimized the possibility of conflict between different tribes and groups.

The last time the census asked about ethnicity was in 1946, and responses showed a highly heterogeneous population in Botswana. For example, in the Ngwato region, only 20% considered themselves unconditionally Ngwato people; although there were also representatives of other Tswana tribes present, for whom the Setswana language was not their native language. This extreme heterogeneity was subsequently smoothed out through targeted government action, as well as through the relatively inclusive institutions of the Tswana tribes - just as the smoothing out of population heterogeneity in Britain (for example, the difference between England and Wales) was the result of British state policy. Since independence, the question of ethnicity was no longer asked in censuses - now everyone in Botswana was Tswana.

Botswana achieved remarkable success after the fall of colonialism because Seretse Khama, Quette Masire and the Democratic Party led Botswana towards inclusive economic and political institutions. When diamonds were discovered in the country in the 1970s, it did not lead to civil war but provided a strong financial base for the government, which used profits from diamond mining to invest in public services. Much less incentive was to conspire or overthrow the government in order to gain control of the state. Inclusive political institutions have brought political stability and created the basis for inclusive economic institutions. In a virtuous feedback loop, inclusive economic institutions ensured the sustainability of corresponding political institutions.

Botswana broke the mold because it began to build inclusive institutions at a critical inflection point at independence. The Botswana Democratic Party and its elite, which included Khama himself, did not try to establish a dictatorial regime that could enrich it at the expense of the rest of society. Here again we see an example of how established institutions react at critical turning points. Unlike most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Botswana already had tribal institutions that provided a degree of centralization of power, but at the same time had some pluralistic features. In addition, the country's economic elite gained much from securing secure property rights.

No less important is the fact that the unpredictable course of history in in this case was directed in a direction favorable to Botswana. Seretse Khama and Quett Masire were not like Siaku Stevens or Robert Mugabe. They worked honestly to build inclusive institutions on the basis of traditional Tswana tribal institutions. All this made it much more likely for Botswana to succeed in building inclusive institutions, while the rest of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa either did not even try to follow this path, or their attempts failed.

Each country has its own history. The history of Botswana, an African country located in Southern Africa, is very interesting and unusual.

The history of the country before the 19th century has not been sufficiently studied. Scientists have established that the autochthonous population - the Bushmen and Hottentots - was pushed into the interior of the Kalahari by the Bantu tribes, who in very distant times came here from the modern Transvaal (province of South Africa). Already more than a thousand years ago, Bantus inhabited the eastern coast of Africa as far as Natal, and some of these tribes came from the areas of what is now Zambia.

The complex and lengthy process of formation of the Tswana tribes in Botswana was largely the result of migrations. African researcher I. Shapera wrote: “With some confidence, we can only say that the Tswana inhabited the eastern half of the country already from 1600 AD.” Over the next two centuries, “each of the existing family branches gave rise to more and more new shoots. The history of the Tswana tribes is rich in schisms. Usually, a dissatisfied member of the leader’s family, along with his supporters, went to distant lands, where an independent tribe arose, taking its name from the name of the leader.” .

The Tswana, the people who inhabit Botswana, believe that their main tribes descended from the people ruled by Chief Masilo, who lived in the mid-17th century. One of his two sons, Malope, had three sons - Kwena, Ngwato and Ngwaketse, from whom the names of the modern tribes of Botswana come.

IN early XIX V. most of South Africa was subject to expansion by the Zulu, led by the warlike leader Chaka, and the Ndebele, a side branch of this ethnic group, led by the leader Mzilikazi. The wars with the Zulu, who invaded Tswana territory, were especially bloody and devastating.

IN mid-19th V. Tswana conquered indigenous people- Bushmen - and occupied the areas that belonged to them west of the Transvaal up to the Kalahari Desert. In 1820 Representative of the London Missionary Society Robert Moffat founded the first Christian mission among the Tswana in Kuruman (the territory of modern South Africa).

In 1820-1870 There were tribal feuds among the Tswana and conflicts with the Afrikaner trekkers who were expanding the territory of their possessions. Only the most numerous Tswana tribes, such as, for example, the Ngwato led by the leader Sekgoma, could resist the Afrikaners. Meanwhile, another English missionary, David Livingstone, founded a mission among the Kwena tribe and managed to convert many of them to Christianity. In 1872, Sekgoma Khama III's son, who had been baptized in 1862, became the head of the largest Tswana tribe, the Ngwato. During his long reign, he successfully defended himself against the Ndebele and implemented various reforms in his domains.

Meanwhile, relations between the Tswana and the Afrikaners living in the Transvaal deteriorated. In 1876, Chief Khama and the leaders of other Tswana tribes petitioned the British High Commissioner to South Africa to accept his people under British protection. In 1878, the territory controlled by the leaders who asked for help was occupied by British troops. When these troops left three years later, the Afrikaners invaded.

Europeans appeared on the territory of what is now Botswana in the 18th century, and constant contacts between the Tswana and immigrants from Europe were established at the beginning of the 19th century. The first Europeans to become acquainted with the Tswana settlement area on the eastern borders of the Kalahari are considered to be the Englishmen Peter Tratter and William Sommerville. In 1801 they entered the area north of the Orange River. In 1812-1813 John Campbell, sent by the London Missionary Society, explored some of the other rivers of the Orange system.

Major geographical discoveries in the southern part of the continent are associated primarily with the name of Livingstone, who opened South Africa to science. His book Missionary Travel and Exploration in South Africa, published in London in 1857, was considered at that time a kind of encyclopedia scientific knowledge about this region.

In 1836, the court of the Cape Colony, which belonged to the British, established its jurisdiction over part of the territory inhabited by the Tswana tribes, but the Tswana leaders still managed to maintain their independence.

In 1852, the Boers of the Transvaal achieved recognition of their independence from England, and from that moment the Tswana’s struggle against continuous Boer raids began. However, the Tswana leaders, who took advantage of the Anglo-Boer contradictions, managed to defend their independence for another three decades.

In 1884, the British government, fearing intervention from Germany, sent missionary John Mackenzie as its representative with the rank of Deputy Commissioner for South Africa. In 1885, Great Britain defeated the Afrikaners and, with the consent of Khama and other influential chiefs, the entire territory inhabited by the Tswana people was declared a British protectorate under the name Bechuanaland. The administrative center of the protectorate was located outside the territory of Bechuanaland (the only case in world practice): it was controlled from Mafeking, located in what is now South Africa, near the border. In 1895, the southern part of Bechuanaland was annexed to the Cape Colony, while the northern part retained the status of an English protectorate.

Although Great Britain officially declared its respect for the laws and customs of African peoples, in 1895 its government approved the transfer of control of Bechuanaland private company British South Africa Company founded by Cecil Rhodes. This move by London raised concerns among the Tswana people, and Khama, accompanied by two other chiefs, traveled to England to protest the deal. As a result, Britain agreed to maintain its control of the protectorate, and the Tswana chiefs agreed to transfer a narrow strip of land in the east to the company for the construction of a railway.

Despite the fact that, as of 1964, all power in Bechuanaland belonged to the British High Commissioner in South Africa, the real power was with the commissioner who was permanently stationed in Mafeking (South Africa). For several years after 1891, all the activities of the British administration were reduced mainly to protecting the territory of Bechuanaland from the encroachments of other foreign powers. The solution to all internal issues was left to the tribal leaders. The situation that had changed by 1934 and demands from Africans to improve the management system prompted London to expand the powers of the central government.

With the creation of African Advisory Councils in 1920, the Tswana were able to participate in the work government agencies Bechuanaland. In the same year, an advisory body of the European population was created, and in 1950 a joint council. As a result, the role of Africans in discussing governance issues has increased. In 1959 The constitutional committee of the Joint Council put forward a proposal to create a Legislative Council. London approved the proposal, and in 1960 the Bechuanaland Constitution was promulgated. In the 1961 Legislative Council elections, most of the seats allocated to Africans were won by supporters of Seretse Khama, the grandson of Chief Khama III. In 1965, a constitution was adopted that established internal self-government and provided for the creation of a cabinet of ministers.

During the Second World War and in the immediate post-war years, no upheavals were noted in Bechuanaland. The gradual social change. There was a process of stratification of the peasantry, conflicts between leaders and community members became more frequent. The education system expanded. In 1946, the number of students in Bechuanaland exceeded 20 thousand. The number of people receiving secondary education increased. Some Africans managed to enter foreign Universities.

During the Second World War, 10 thousand Tswana participated in the combat operations of the British army in the Middle East and Europe. Soldiers returning from the war, who had relatively high level political consciousness, became in the first post-war years the main exponents of the dissatisfaction of the masses with the colonial order. These grievances subsequently led to Botswana's independence.

On September 30, 1966, Botswana was declared an independent state. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), created by Seretse Khama, consistently won the parliamentary elections of 1969, 1974 and 1979. The main opposition party was the more radical Botswana National Front (BNF). After the death of Seretse Khama on July 13, 1980, the country was led by former Vice President Quette Ketumile Masire. In the next elections in 1984 and 1989, Masire and the DPB easily achieved victory. However, in the 1989 elections, the NFB received almost a third of the votes. In the 1994 elections, the opposition already gained 37% of the vote, and the number of seats it received increased from 3 to 13. The NFB also managed to win all 6 additional seats from urban polling stations allocated to ensure representation of the increased urban population.

With the creation of an African majority government in South Africa in 1994, Botswana was freed from a number of political and economic problems caused by the apartheid system. The headquarters of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) is located in Botswana. Botswana makes a worthy contribution to supporting the activities of UN peacekeeping forces in conflict areas in Africa. After the resignation of President Masire in 1998, the country was led by former vice-president and finance minister Festus Mogae. He appointed Seretse Khama's son, Chief Ian Khama, a former commander of the country's armed forces, as his new vice-president. The election of President F. Mogae will gradually lead the country to achieve even greater political stability, because his government policies are recognized as one of the most optimal on the entire African continent.