N.V. Gogol "Dead Souls": description, heroes, analysis of the poem

Provincial society in Gogol’s poem “Dead Souls”

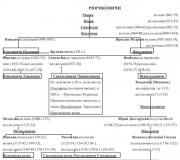

In the notes to the first volume of Dead Souls, Gogol wrote: “The idea of the city. Gossip that went beyond limits, how all this arose from idleness and took on the expression of the funny in highest degree... The whole city with all the whirlwind of gossip is a transformation of the inactivity of life of all humanity in the mass.” This is how the writer characterizes the provincial town of NN and its inhabitants. It must be said that provincial society Gogol's poem, as well as Famusov’s in Griboedov’s play “Woe from Wit,” can be divided into masculine and feminine. The main representatives of male society are provincial officials. Undoubtedly, the theme of officialdom is one of the central themes in Gogol’s work. The writer dedicated many of his works, such as the story “The Overcoat” or the comic play “The Inspector General” various aspects official life. In particular, in “Dead Souls” we are presented with provincial and higher St. Petersburg officials (the latter in “The Tale of Captain Kopeikin”).

Exposing the immoral, vicious, flawed natures of officials, Gogol uses the technique of typification, because even in vivid and individual images (such as the police chief or Ivan Antonovich), common features inherent in all officials are revealed. Already creating portraits of officials using the technique of reification, the author, without saying anything about their spiritual qualities, character traits, only described the “wide backs of heads, tailcoats, frock coats of provincial cut...” of clerical officials or “very thick eyebrows and a somewhat winking left eye.” prosecutor, spoke about the deadness of souls, moral backwardness and baseness. None of the officials bother themselves with concerns about government affairs, and the concept of civic duty and public good is completely alien to them. Idleness and idleness reign among the bureaucrats. Everyone, starting with the governor, who “was a great good-natured person and embroidered on tulle,” spends their time pointlessly and unproductively, not caring about fulfilling their official duty. It is no coincidence that Sobakevich notes that “... the prosecutor is an idle person and, probably, sits at home, ... the inspector of the medical board is also, probably, an idle person and went somewhere to play cards, ... Trukhachevsky, Bezushkin - they are all they burden the earth for nothing...” Mental laziness, insignificance of interests, dull inertia form the basis of the existence and character of officials. Gogol speaks with irony about the degree of their education and culture: “... the chairman of the chamber knew “Lyudmila” by heart, ... the postmaster delved into ... philosophy and made extracts from “The Key to the Mysteries of Nature,” ... whoever read “ Moskovskie Vedomosti”, who haven’t even read anything at all.” Each of the provincial governors sought to use their position for personal purposes, seeing in it a source of enrichment, a means to live freely and carefree, without spending any labor. This explains the bribery and embezzlement that reigns in bureaucratic circles. For bribes, officials are even capable of committing the most terrible crime, according to Gogol - instituting an unfair trial (for example, they “hushed up” the case of merchants who “death” each other during a feast). Ivan Antonovich, for example, knew how to benefit from every business, being an experienced bribe-taker, he even reproached Chichikov that he “bought peasants for a hundred thousand, and gave one little white for their work.” Solicitor Zolotukha is “the first grabber and in Gostiny Dvor I visited as if I were visiting my own storeroom.” He had only to blink, and he could receive any gifts from the merchants who considered him a “benefactor,” for “even though he will take it, he will certainly not give you away.” For his ability to take bribes, the police chief was known among his friends as a “magician and miracle worker.” Gogol says with irony that this hero “managed to acquire modern nationality,” for the writer more than once denounces the anti-nationalism of officials who are absolutely ignorant of hardships peasant life who consider the people “drunkards and rioters.” According to officials, peasants are “a very empty and insignificant people” and “they must be kept with a tight grip.” It is no coincidence that the story about Captain Kopeikin is introduced, for in it Gogol shows that anti-nationality and anti-people character are also characteristic of the highest St. Petersburg officials. Describing bureaucratic St. Petersburg, the city “ significant persons”, the highest bureaucratic nobility, the writer denounces their absolute indifference, cruel indifference to the fate of the defender of the homeland, doomed to certain death from hunger... This is how officials, indifferent to the life of the Russian people, indifferent to the fate of Russia, neglecting their official duty, use their power for the sake of personal benefits and are afraid of losing the opportunity to carefreely enjoy all the “benefits” of their position, therefore the provincial governors maintain peace and friendship in their circle, where an atmosphere of nepotism and friendly harmony reigns: “... they lived in harmony with each other, treated each other completely friendly, and their conversations bore the stamp of some special innocence and meekness...” Officials need to maintain such relationships in order to collect their “income” without any fear...

This is the male society of the city of NN. If we characterize the ladies of the provincial town, then they are distinguished by external sophistication and grace: “many ladies are well dressed and in fashion,” “there is an abyss in their outfits...”, but internally they are as empty as men, their spiritual life poor, interests primitive. Gogol ironically describes the “good tone” and “presentability” that distinguish the ladies, in particular their manner of speaking, which is characterized by extraordinary caution and decency in expressions: they did not say “I blew my nose,” preferring to use the expression “I relieved my nose with a handkerchief,” or in general the ladies spoke French, where “words appeared much harsher than those mentioned.” The ladies’ speech, a true “mixture of French with Nizhny Novgorod,” is extremely comical.

Describing the ladies, Gogol even characterizes their essence at the lexical level: “...a lady fluttered out of the orange house...”, “...a lady fluttered up the folded steps...” Using metaphors, the writer “fluttered” and “fluttered out” shows the “lightness” characteristic of a lady, not only physical, but also spiritual, inner emptiness and underdevelopment. Indeed, the largest part of their interests is outfits. So, for example, a lady who is pleasant in all respects and simply pleasant is having a meaningless conversation about the “cheerful chintz” from which the dress of one of them is made, about the material where “the stripes are very narrow, and eyes and paws go through the entire stripe... " In addition, gossip plays a big role in the lives of ladies, as well as in the life of the entire city. Thus, Chichikov’s purchases became the subject of conversation, and the “millionaire” himself immediately became the subject of ladies’ adoration. After suspicious rumors began to circulate about Chichikov, the city was divided into two “opposite parties.” “The women’s team was exclusively concerned with the kidnapping of the governor’s daughter, and the men’s, the most clueless, turned their attention to dead souls”... Such is the pastime provincial society, gossip and empty talk are the main occupation of the city's residents. Undoubtedly, Gogol continued the traditions established in the comedy “The Inspector General”. Showing the inferiority of provincial society, immorality, baseness of interests, spiritual callousness and emptiness of the townspeople, the writer “collects everything bad in Russia”, with the help of satire exposes the vices of Russian society and realities contemporary writer reality, so hated by Gogol himself.

V. PETROV, psychologist.

If we are interested in the problem of man and we want to understand what is truly human, eternal in people, and science can do little to help in this, then our path, undoubtedly, first of all, is to F. M. Dostoevsky. It was him who S. Zweig called “the psychologist of psychologists”, and N.A. Berdyaev - “the great anthropologist”. “I know only one psychologist - this is Dostoevsky,” - contrary to his tradition of overthrowing all earthly and heavenly authorities, wrote F. Nietzsche, who, by the way, had his own and far from superficial view of man. Another genius, N.V. Gogol, showed the world people with an extinguished spark of God, people with dead soul.

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, L. Tolstoy, Stendhal, Proust provide much more for understanding human nature than academic philosophers and scientists - psychologists and sociologists...

N. A. Berdyaev

EVERY PERSON HAS AN "UNDERGROUND"

Dostoevsky is difficult for readers. Many of them, especially those who are accustomed to seeing everything clear and easily explained, do not accept the writer at all - he deprives them of the feeling of comfortable life. It's hard to immediately believe that life path it may be just like this: in continuous oscillations between extremes, when a person drives himself into a corner at every step, and then, as if in a state of drug withdrawal known to our time, turning inside out, gets out of the dead end, commits actions and then, repenting of them, suffers under the torture of self-humiliation. Which of us admits that we can “love pain and fear”, be in “ecstasy from the painful state of baseness”, live, feeling “a terrible disorder in everything”? Even dispassionate science puts this outside the brackets of the so-called norm.

By the end of the 20th century, psychologists suddenly began to say that they were finally approaching that understanding of the intimate mechanisms of human mental life, as Dostoevsky saw them and showed them in his heroes. However, a science built on logical foundations (and there cannot be any other science) cannot understand Dostoevsky, because his ideas about man cannot be bound by a formula, a rule. We need a super-scientific psychological laboratory here. It was given to a brilliant writer, was found by him not in university classrooms, but in the boundless torments of his own life.

The entire 20th century was waiting for the “death” of Dostoevsky’s heroes and himself as a classic, a genius: they say that everything he wrote was outdated, left in the 19th century, in old petty-bourgeois Russia. The loss of interest in Dostoevsky was predicted after the fall of the autocracy in Russia, then in the middle of the 20th century, when a boom in the intellectualization of the population began, and finally, after the collapse of Soviet Union and the victory of the “brain civilization” of the West. But what really happens? His heroes are illogical, divided, tormented, constantly fighting with themselves, not wanting to live according to the same formula with everyone, guided only by the principle of “satiety” - and at the beginning of the 21st century they remain “more alive than all the living”. There is only one explanation for this - they are true.

The writer managed to show a person not in some standard, civilized and familiar way public opinion option, but in complete nudity, without masks or camouflage suits. And it is not Dostoevsky’s fault that this view turned out to be, to put it mildly, not entirely salon-like and that it is unpleasant for us to read the truth about ourselves. After all, as another genius wrote, we love “the deception that elevates us” more.

Dostoevsky saw the beauty and dignity of human nature not in specific manifestations of life, but in those heights from which it originates. Its distortion here is inevitable. But beauty remains if a person has not come to terms with vanity and dirt, and therefore rushes about, strives, tries, again and again becoming covered in impurities, to cleanse himself and preserve the freedom of his soul.

Forty years before Freud, Dostoevsky declared: a person has an “underground”, where another, “underground” and independent person lives and actively acts (more precisely, counteracts). But this is a completely different understanding of the human underside than in classical psychoanalysis. Dostoevsky's "Underground" is also a boiling cauldron, but not of imperative, unidirectional drives, but of continuous confrontations and transitions. No benefit can be a permanent goal, each aspiration (immediately upon its realization) is replaced by another, and any stable system of relationships becomes a burden.

And yet there is one strategic goal, a “special benefit” in this “terrible disorder” of the human “underground”. Inner man With each of his actions he does not allow his real-life opponent to finally and irrevocably “get hooked” on something earthly, to become captive of one unchanging belief, to become a “pet” or a mechanical robot, living strictly according to instincts or a program laid down by someone. This is the highest meaning of the existence of the mirror double, he is guarding human freedom and the opportunity given to him from above through this freedom special relationship with God blessing.

And therefore, Dostoevsky’s heroes constantly conduct an internal dialogue, argue with themselves, repeatedly changing their own position in this dispute, alternately defending polar points of view, as if the main thing for them is not to be forever captive to one belief, one life goal. This feature of Dostoevsky’s understanding of man was noted by the literary critic M. M. Bakhtin: “Where they saw one quality, he revealed in it the presence of another, opposite quality. Everything that seemed simple in his world became complex and multi-component. In every voice he knew how to hear two arguing voices, in every gesture he caught confidence and uncertainty at the same time..."

All the main characters of Dostoevsky - Raskolnikov ("Crime and Punishment"), Dolgoruky and Versilov ("The Teenager"), Stavrogin ("Demons"), the Karamazovs ("The Brothers Karamazov") and, finally, the hero of "Notes from Underground" - are endlessly contradictory . They are in continuous movement between good and evil, generosity and vindictiveness, humility and pride, the ability to confess in the soul highest ideal and almost simultaneously (or a moment later) commit the greatest meanness. Their destiny is to despise man and dream of the happiness of mankind; having committed a mercenary murder, disinterestedly give away the loot; to always be in a “fever of hesitation, decisions made forever and a minute later repentance coming again.”

Inconsistency, the inability to clearly determine one’s intentions leads to a tragic ending for the heroine of the novel “The Idiot” Nastasya Filippovna. On her birthday, she declares herself the bride of Prince Myshkin, but immediately leaves with Rogozhin. The next morning he runs away from Rogozhin to meet with Myshkin. After some time, preparations begin for the wedding with Rogozhin, but future bride disappears again with Myshkin. Six times the mood pendulum swings Nastasya Filippovna from one intention to another, from one man to another. The unfortunate woman seems to be rushing between two sides of her own “I” and cannot choose the only one, unshakable, until Rogozhin stops these throwing with a blow of a knife.

Stavrogin, in a letter to Daria Pavlovna, is perplexed about his behavior: he exhausted all his strength in debauchery, but did not want it; I want to be decent, but I do mean things; In Russia everything is foreign to me, but I can’t live in any other place. In conclusion he adds: “I will never, never be able to kill myself...” And soon after that he commits suicide. “If Stavrogin believes, then he does not believe that he believes. If he does not believe, then he does not believe that he does not believe,” Dostoevsky writes about his character.

"PEACE OF MIND IS A MIND OF MEANNESS"

The struggle of multidirectional thoughts and motives, constant self-execution - all this is torment for a person. Maybe this state is not his natural feature? Perhaps it is inherent only to a certain human type or national character, for example Russian, as many critics of Dostoevsky like to argue (in particular, Sigmund Freud), or it is a reflection of a certain situation that has developed in society at some point in its history - for example, in Russia in the second half of the 19th century?

The “psychologist of psychologists” rejects such simplifications; he is convinced: this is “the most common trait in people..., a trait characteristic of human nature in general.” Or, as his hero from “The Teenager,” Dolgoruky, says, the constant clash of different thoughts and intentions is “the most normal state, and not at all a disease or damage.”

At the same time, it must be recognized that Dostoevsky’s literary genius was generated and in demand by a certain era. The second half of the 19th century is a time of transition from patriarchal existence, which still retained the real tangibility of the concepts of “soulfulness,” “cordiality,” and “honor,” to a rationally organized life devoid of former sentimentality in conditions of all-conquering technization. Another, already frontal, attack is being prepared on the human soul, and the emerging System, with even greater impatience than in previous times, is determined to see it “dead.” And, as if anticipating the impending slaughter, the soul begins to rush about with particular despair. This was given to Dostoevsky to feel and show. After his era, mental tossing did not cease to exist normal condition man, however, in turn, the 20th century has already succeeded a lot in rationalizing our inner world.

"Normal state of mind“It was not only Dostoevsky who felt. As is known, Lev Nikolaevich and Fyodor Mikhailovich did not really honor each other in life. But each of them was given (like no experimental psychology) to see the deepest in a person. And in this vision the two geniuses were united.

Alexandra Andreevna Tolstaya, great aunt and soulmate Lev Nikolaevich, complains to him in a letter dated October 18, 1857: “We always expect peace to settle down, peace of mind to come to our souls. We feel bad without it.” This is just a devilish calculation, a very young writer writes in response, the bad in the depths of our soul desires stagnation, the establishment of peace and tranquility. And then he continues: “To live honestly, you have to rush, get confused, fight, make mistakes, start and give up, and start again and give up again, and always struggle and lose... And calmness is spiritual meanness. This is the bad side of our soul and desires peace, without foreseeing that achieving it is associated with the loss of everything that is beautiful in us, not human, but from there.”

In March 1910, rereading his old letters, Lev Nikolaevich highlighted this phrase: “And now I would not say anything different.” The genius maintained the conviction all his life: peace of mind, which we are looking for, is destructive primarily for our soul. It was sad for me to part with the dream of calm happiness, he notes in one of his letters, but this is “a necessary law of life,” the destiny of man.

According to Dostoevsky, man is a transitional being. Transitivity is the main, essential thing in it. But this transition does not have the same meaning as Nietzsche and many other philosophers, who see in the transitional state something transitory, temporary, unfinished, not brought to the norm, and therefore subject to completion. Dostoevsky has a different understanding of transition, which only towards the end of the 20th century begins to gradually break through to the forefront of science, but is still in the “Through the Looking Glass” of people’s practical life. He shows through his heroes that there are no permanent states in human mental activity at all, there are only transitional ones, and only they make our soul (and man) healthy and viable.

The victory of one side - even, for example, absolutely moral behavior - is possible, according to Dostoevsky, only as a result of the renunciation of something natural in oneself that cannot be reconciled with any finality in life. There is no unambiguous place “where living things live”; there is no specific state that can be called the only desirable one - even if you “drown yourself completely in happiness.” There is no trait that determines everything in a person, except the need for transitions with obligatory suffering and rare moments of joy. For duality and the fluctuations and transitions that inevitably accompany it are the path to something Higher and True, with which “the spiritual outcome is connected, and this is the main thing.” Only outwardly it seems that people are rushing chaotically and aimlessly from one to another. In fact, they are in an unconscious internal search. According to Andrei Platonov, they do not wander, they search. And it is not a person’s fault that more often than not, on either side of the search amplitude, he stumbles upon a blank wall, finds himself in a dead end, and again and again finds himself captive of the untrue. This is his fate in this world. Hesitation allows him at least not to become a complete captive of the untrue.

The typical hero of Dostoevsky is far from the ideal by which we build family and school education today, towards which our reality is oriented. But he, undoubtedly, can count on the love of the Son of God, who also in his earthly life was more than once tormented by doubts and, at least for a while, felt like a helpless child. Of the heroes of the New Testament, “Dostoevsky’s man” is more similar to the doubting and self-punishing tax collector whom Jesus called to be an apostle than to the Pharisees and scribes we understand well.

"And truly, I love you because you do not know how to live today, oh superior people!"

Friedrich Nietzsche

The highest comes, Dostoevsky believed, only to those who have not been completely and irrevocably possessed by anything earthly, who are capable of purifying their soul through suffering. This is the only reason why Prince Myshkin’s pronounced childishness and inability to adapt to real life turn into spiritual insight and the ability to foresee events. Even the ability for deep human experience and remorse that awakened in Smerdyakov (from The Brothers Karamazov) at the end of all his unclean deeds makes it possible to revive to life the previously deeply walled-up “face of God.” Smerdyakov dies, refusing to reap the fruits of his crime. Another character of Dostoevsky, Raskolnikov, having committed a mercenary murder, after painful experiences, gives all the money to the family of the deceased Marmeladov. Having completed this act of healing for the soul, he suddenly feels himself, after long, seemingly eternal suffering, in the power of “one, new, immense sensation of a suddenly surging full and powerful life.”

Dostoevsky rejects the rationalistic idea of human happiness in " Crystal Palace“, where everything will be “calculated according to the tablet.” A person is not “a damask in an organ shaft.” In order not to go out, to remain alive, the soul must continuously flicker, break the darkness of what has been established once and for all, what can already be defined as “twice two four." Therefore, she insists, demands from a person to be new every day and moment, continuously, in agony, to look for another solution, as soon as the situation becomes a dead pattern, to continuously die and be born.

This is the condition for the health and harmonious life of the soul, therefore, the main benefit of a person, “the most profitable benefit that is dearest to him.”

THE BITTER SHARE OF GOGOL

Dostoevsky showed the world a man who was tossing about, painfully searching for more and more new solutions and therefore always alive, whose “spark of God” flickers continuously, over and over again breaking the veil of the layers of the everyday.

As if complementing the picture of the world, another genius, shortly before this, saw and showed the world people with an extinguished spark of God, with a dead soul. Gogol's poem "Dead Souls" was initially rejected even by the censor. There is only one reason - in the name. For an Orthodox country, it was considered unacceptable to assert that souls could be dead. But Gogol did not retreat. Apparently, in this name it was for him special meaning, not fully understood by many, even people spiritually close to him. Later writer Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Rozanov, Berdyaev were repeatedly criticized for this name. The general motive of their objections is this: there cannot be “dead souls” - in everyone, even the most insignificant person there is light, which, as it is said in the Gospel, “shines in darkness.”

However, the title of the poem was justified by its heroes - Sobakevich, Plyushkin, Korobochka, Nozdryov, Manilov, Chichikov. Similar to them are other heroes of Gogol’s works - Khlestakov, the mayor, Akaki Akakievich, Ivan Ivanovich and Ivan Nikiforovich... These are ominous and lifeless “wax figures” personifying human insignificance, “eternal Gogol’s dead”, from the sight of which “a person can only despise a person" (Rozanov). Gogol depicted “entirely empty, insignificant and, moreover, morally vile and disgusting creatures” (Belinsky), showed “brutalized faces” (Herzen). Gogol doesn't have human images, but there are only “muzzles and faces” (Berdyaev).

Gogol himself was no less horrified by his own creations. These, in his words, are “pig snouts,” frozen human grimaces, some soulless things: either “slaves of unnecessary things” (like Plyushkin), or having lost their individual features and becoming a kind of serial production item (like Dobchinsky and Bobchinsky), or having transformed themselves into devices for copying papers (like Akaki Akakievich). It is known that Gogol suffered deeply because he produced such “images” and not positive edifying heroes. In fact, he drove himself crazy with this suffering. But I couldn’t help myself.

Gogol always admired Homer’s “Odyssey” and the majestic beauty of the actions of its heroes; he wrote with extraordinary warmth about Pushkin and his ability to show all that is great in a person. And all the more difficult did I feel in the vicious circle of my insignificant images, covered with laughter on top, but inside deathly gloomy images.

Gogol tried to find and show something positive, bright in people. They say that in the second volume of Dead Souls he somewhat transformed the characters we know, but was forced to burn the manuscript - he was unable to revive his heroes. A most interesting phenomenon: he suffered, passionately wanted to change, improve, but, despite all his talent, he could not do it.

The personal fate of Dostoevsky and Gogol is equally painful - the fate of a genius. But if the first, having gone through the deepest suffering, was able to see the essence of man in a soul actively resisting the pressure of the world, then the second discovered only a soulless, but purposefully acting “image”. It is often said that Gogol's characters are from a demon. But perhaps the Creator, through the genius of the writer, decided to show what a person will be like who has lost the spark of God, who has become a complete product of demonization (read rationalization) of the world? Providence willed it at the threshold of an era scientific and technological progress to warn humanity of the profound consequences of future actions.

It is impossible to depict a sincere person in the form of an unambiguous, dead diagram, to imagine his life always cloudless and happy. In our world, he is forced to worry, doubt, search for solutions in torment, blame himself for what is happening, worry about other people, be mistaken, make mistakes... and inevitably suffer. And only with the “death” of the soul does a person acquire a certain stability - he always becomes calculating, cunning, ready to lie and pretend, to break all obstacles on the way to a goal or to satisfy a passion. This gentleman no longer knows empathy, never feels guilty, and is ready to see in those around him the same actors as himself. With a grimace of superiority, he looks at all doubters - from Don Quixote and Prince Myshkin to his contemporaries. He doesn't understand the benefit of doubt.

Dostoevsky was convinced that man is inherently good. The evil in him is secondary - life makes him evil. He showed a man split in two and, as a result, suffering immensely. Gogol was left with “secondary” people - finished products of a steadily formalizing life. As a result, he gave characters more oriented not to his time, but to the coming century. That’s why “Gogol’s dead” are tenacious. It doesn't take much to make them look completely normal. modern people. Gogol also remarked: “My heroes are not villains at all; if I had added just one good trait to any of them, the reader would have made peace with them all.”

WHAT BECAME THE IDEAL OF THE XX CENTURY?

Dostoevsky, for all his interest in living people, also has one hero completely “without a soul.” He is like a scout from another time, from the approaching new century. This is the socialist Pyotr Verkhovensky in "Demons". The writer, through this hero, also gives a forecast for the coming century, predicts an era of struggle with mental activity and the flourishing of “demonicism.”

A social reformer, a “benefactor” of humanity, striving to force everyone to happiness, Verkhovensky sees the future well-being of people in dividing them into two unequal parts: one tenth will dominate the nine-tenths, who, through a series of rebirths, will lose the desire for freedom and spirituality dignity. “We will kill desire,” Verkhovensky proclaims, “we will extinguish every genius in infancy. Everything is to the same denominator, complete equality.” He considers such a project to be the only possible one in creating an “earthly paradise.” For Dostoevsky, this hero is one of those whom civilization has made “nastier and more bloodthirsty.” However, it is this kind of firmness and consistency in achieving the goal at any cost that will become the ideal of the 20th century.

As N.A. Berdyaev writes in the article “Gogol in the Russian Revolution,” there was a belief that “the revolutionary thunderstorm will cleanse us of all filth.” But it turned out that the revolution only exposed, made everyday what Gogol, suffering for his heroes, bashfully covered with a touch of laughter and irony. According to Berdyaev, "scenes from Gogol are played out at every step in revolutionary Russia". There is no autocracy, and the country is full of "dead souls." "There are masks and doubles everywhere, grimaces and shreds of a person, nowhere can you see a clear human face. Everything is built on lies. And it is no longer possible to understand what is true, what is false, what is false in a person. Everything is probably fake."

And this is not only a problem for Russia. In the West, Picasso artistically depicts the same non-humans that Gogol saw. The “folding monsters of cubism” are similar to them. IN public life"Khlestakovism" is flourishing in all civilized countries - especially in the activities of political leaders of any level and persuasion. Homo Sovetikus and Homo Ekonomikus are no less ugly in their uniqueness, “one-dimensionality” than Gogol’s “images”. We can say with confidence that they are not from Dostoevsky. Modern “dead souls” have only become more educated, learned to be cunning, smile, and talk intelligently about business. But they are soulless.

Therefore, it no longer seems an exaggeration that the famous American publicist E. Shostrom described in his book “Anti-Carnegie...” the instructions given by an experienced Mexican to his fellow countrymen traveling to the USA for the first time: “Americans - the most beautiful people, but there is one point that bothers them. You shouldn't tell them that they are corpses." According to E. Shostrom, here - the utmost precise definition"diseases" of modern man. He is dead, he is a doll. His behavior is indeed very similar to the "behavior" of a zombie. He has serious difficulties with emotions, changing experiences, the ability to live and react to what is happening according to the “here and now” principle, change decisions and suddenly, unexpectedly even for himself, without any calculation, put his “want” above all else.

"The true essence of the 20th century is slavery."

Albert Camus

N.V. Gogol showed the life of a “man in a case” long before the thinkers of the 20th century suddenly discovered that the spiritual world of their contemporaries was more and more locked in a “cage” of unambiguous beliefs, entangled in networks of imposed attitudes.

In the notes to the first volume of Dead Souls, Gogol wrote: “The idea of the city. Gossip that has crossed the limits, how all this arose from idleness and took on the expression of the ridiculous to the highest degree... The whole city with all the whirlwind of gossip is a transformation of the inactivity of the life of all humanity en masse.” This is how the writer characterizes the provincial town of NN and its inhabitants. It must be said that the provincial society of Gogol’s poem, as well as Famusov’s in Griboedov’s play “Woe from Wit,” can be conditionally divided into male and female. The main representatives of male society are provincial officials. Undoubtedly, the theme of bureaucracy is one of the central themes in Gogol’s work. The writer devoted many of his works, such as the story “The Overcoat” or the comic play “The Inspector General,” to various aspects of bureaucratic life. In particular, in “Dead Souls” we are presented with provincial and higher St. Petersburg officials (the latter in “The Tale of Captain Kopeikin”).

Exposing the immoral, vicious, flawed natures of officials, Gogol uses the technique of typification, because even in vivid and individual images (such as the police chief or Ivan Antonovich), common features inherent in all officials are revealed. Already creating portraits of officials using the technique of reification, the author, without saying anything about their spiritual qualities, character traits, only described the “wide backs of heads, tailcoats, frock coats of provincial cut...” of clerical officials or “very thick eyebrows and a somewhat winking left eye.” prosecutor, spoke about the deadness of souls, moral backwardness and baseness. None of the officials bother themselves with concerns about state affairs, and the concept of civic duty and public good is completely alien to them. Idleness and idleness reign among the bureaucrats. Everyone, starting with the governor, who “was a great good-natured person and embroidered on tulle,” spends their time pointlessly and unproductively, not caring about fulfilling their official duty. It is no coincidence that Sobakevich notes that “... the prosecutor is an idle person and, probably, sits at home, ... the inspector of the medical board is also, probably, an idle person and went somewhere to play cards, ... Trukhachevsky, Bezushkin - they are all they burden the earth for nothing...” Mental laziness, insignificance of interests, dull inertia form the basis of the existence and character of officials. Gogol speaks with irony about the degree of their education and culture: “... the chairman of the chamber knew “Lyudmila” by heart, ... the postmaster delved into ... philosophy and made extracts from “The Key to the Mysteries of Nature,” ... whoever read “ Moskovskie Vedomosti”, who haven’t even read anything at all.” Each of the provincial governors sought to use their position for personal purposes, seeing in it a source of enrichment, a means to live freely and carefree, without spending any labor. This explains the bribery and embezzlement that reigns in bureaucratic circles. For bribes, officials are even capable of committing the most terrible crime, according to Gogol - instituting an unfair trial (for example, they “hushed up” the case of merchants who “death” each other during a feast). Ivan Antonovich, for example, knew how to benefit from every business, being an experienced bribe-taker, he even reproached Chichikov that he “bought peasants for a hundred thousand, and gave one little white for their work.” Solicitor Zolotukha is “the first grabber and visited the guest yard as if he were his own pantry.” He had only to blink, and he could receive any gifts from the merchants who considered him a “benefactor,” for “even though he will take it, he will certainly not give you away.” For his ability to take bribes, the police chief was known among his friends as a “magician and miracle worker.” Gogol says with irony that this hero “managed to acquire modern nationality,” for the writer more than once denounces the anti-nationalism of officials who are absolutely ignorant of the hardships of peasant life, who consider the people “drunkards and rebels.” According to officials, peasants are “a very empty and insignificant people” and “they must be kept with a tight grip.” It is no coincidence that the story about Captain Kopeikin is introduced, for in it Gogol shows that anti-nationality and anti-people character are also characteristic of the highest St. Petersburg officials. Describing bureaucratic St. Petersburg, the city of “significant persons”, the highest bureaucratic nobility, the writer exposes their absolute indifference, cruel indifference to the fate of the defender of the homeland, doomed to certain death from hunger... So officials, indifferent to the life of the Russian people, are indifferent to the fate of Russia who neglect their official duty, use their power for personal gain and are afraid of losing the opportunity to carefreely enjoy all the “benefits” of their position, therefore provincial governors maintain peace and friendship in their circle, where an atmosphere of nepotism and friendly harmony reigns: “... they lived between in harmony with themselves, treated themselves in a completely friendly manner, and their conversations bore the stamp of some special innocence and meekness...” Officials need to maintain such relationships in order to collect their “income” without any fear...

This is the male society of the city of NN. If we characterize the ladies of the provincial town, then they are distinguished by external sophistication and grace: “many ladies are well dressed and in fashion,” “there is an abyss in their outfits...”, but internally they are as empty as men, their spiritual life poor, interests primitive. Gogol ironically describes the “good tone” and “presentability” that distinguish the ladies, in particular their manner of speaking, which is characterized by extraordinary caution and decency in expressions: they did not say “I blew my nose,” preferring to use the expression “I relieved my nose with a handkerchief,” or in general the ladies spoke French, where “words appeared much harsher than those mentioned.” The ladies’ speech, a true “mixture of French with Nizhny Novgorod,” is extremely comical.

Describing the ladies, Gogol even characterizes their essence at the lexical level: “...a lady fluttered out of the orange house...”, “...a lady fluttered up the folded steps...” Using metaphors, the writer “fluttered” and “fluttered out” shows the “lightness” characteristic of a lady, not only physical, but also spiritual, inner emptiness and underdevelopment. Indeed, the largest part of their interests is outfits. So, for example, a lady who is pleasant in all respects and simply pleasant is having a meaningless conversation about the “cheerful chintz” from which the dress of one of them is made, about the material where “the stripes are very narrow, and eyes and paws go through the entire stripe... " In addition, gossip plays a big role in the lives of ladies, as well as in the life of the entire city. Thus, Chichikov’s purchases became the subject of conversation, and the “millionaire” himself immediately became the subject of ladies’ adoration. After suspicious rumors began to circulate about Chichikov, the city was divided into two “opposite parties.” “The women’s was exclusively concerned with the kidnapping of the governor’s daughter, and the men’s, the most stupid, paid attention to the dead souls.” This is the pastime of provincial society, gossip and empty talk are the main occupation of the city’s residents. Undoubtedly, Gogol continued the traditions established in the comedy “The Inspector General”. Showing the inferiority of provincial society, immorality, baseness of interests, spiritual callousness and emptiness of the townspeople, the writer “collects everything bad in Russia”, with the help of satire he exposes the vices of Russian society and the realities of the contemporary reality of the writer, so hated by Gogol himself.

The poem "Dead Souls" is a mysterious and amazing work. The writer worked on the creation of the poem for many years. He dedicated so much deep creative thought, time and hard work to it. That is why the work can be considered immortal and brilliant. Everything in the poem is thought out to the smallest detail: characters, types of people, their way of life and much more.

The title of the work - "Dead Souls" - contains its meaning. It describes not the dead revision souls of the serfs, but the dead souls of the landowners, buried under the petty, insignificant interests of life. Buying up the dead souls, Chichikov - main character poems - travels around Russia and pays visits to landowners. This happens in a certain sequence: from less bad to worse, from those who still have a soul to those completely soulless.

The first person Chichikov gets to is the landowner Manilov. Behind the external pleasantness of this gentleman lies meaningless daydreaming, inactivity, and feigned love for his family and peasants. Manilov considers himself well-mannered, noble, educated. But what do we see when we look into his office? A pile of ashes, a dusty book that has been open to page fourteen for two years.

Manilov's house is always missing something: only part of the furniture is covered in silk, and two armchairs are covered with matting; The farm is run by a clerk who ruins both the peasants and the landowner. Idle daydreaming, inactivity, limited mental abilities and vital interests, despite seeming intelligence and culture, allow us to classify Manilov as an “idle sky-smoker” who contributes nothing to society. The second estate that Chichikov visited was the Korobochka estate. Her callousness lies in her amazingly petty interests in life. Apart from the prices of honey and hemp, Korobochka doesn’t care much about anything, if not to say that she doesn’t care about anything. The hostess is “an elderly woman, in some kind of sleeping cap, put on hastily, with a flannel around her neck, one of those mothers, small landowners who cry about crop failures, losses and keep their heads somewhat to one side, and meanwhile they are gradually gaining a little money in motley bags..." Even when selling dead souls, Korobochka is afraid to sell things down. Everything that goes beyond her meager interests simply does not exist. This hoarding borders on madness, because “all the money” is hidden and not put into circulation.

Next on Chichikov’s path he meets the landowner Nozdryov, who was gifted with all possible “enthusiasm.” At first he may seem like a lively and active person, but in reality he turns out to be empty. His amazing energy is directed towards continuous carousing and senseless extravagance.

Added to this is another character trait of Nozdryov - a passion for lying. But the lowest and most disgusting thing about this hero is “the passion to spoil his neighbor.” In my opinion, the soullessness of this hero lies in the fact that he cannot direct his energy and talents in the right direction. Next, Chichikov ends up with the landowner Sobakevich. The landowner seemed to Chichikov “very similar to a medium-sized bear.” Sobakevich is a kind of “fist” whom nature “simply hacked away from all over”, without making much of his face: “she grabbed it with an ax once - her nose came out, she grabbed it another time - her lips came out, she picked out her eyes with a large drill and, without scraping them, let go light, saying, “Lives.”

The insignificance and pettiness of Sobakevich’s soul is emphasized by the description of the things in his house. The furniture in a landowner's house is as heavy as the owner. Each of Sobakevich’s objects seems to say: “And I, too, Sobakevich!”

The gallery of landowner “dead souls” is completed by the landowner Plyushkin, whose soullessness has taken on completely inhuman forms. Once upon a time, Plyushkin was an enterprising and hardworking owner. Neighbors came to him to learn “stingy wisdom.” But after the death of his wife, everything went to pieces, suspicion and stinginess increased to the highest degree. Soon the Plyushkin family also fell apart.

This landowner has accumulated huge reserves of “goods”. Such reserves would be enough for several lives. But he, not content with this, walked around his village every day and collected everything he came across and put it in a heap in the corner of the room. Mindless hoarding has led to the fact that a very rich owner is starving his people, and his supplies are rotting in barns.

Bright images stand next to landowners and officials - “dead souls” ordinary people, which are the embodiment of the ideals of spirituality, courage, love of freedom in the poem. These are images of dead and runaway peasants, first of all, Sobakevich’s men: the miracle master Mikheev, the shoemaker Maxim Telyatnikov, the hero Stepan Probka, the skilled stove maker Milushkin. This is also the fugitive Abakum Fyrov, the peasants of the rebel villages of Vshivaya-arrogance, Borovki and Zadirailova.

It seems to me that Gogol in “Dead Souls” understands that a conflict is brewing between two worlds: the world of serfs and the world of landowners. He warns about the upcoming clash throughout the book. And he ends his poem with a lyrical reflection on the fate of Russia. The image of the Rus' Troika affirms the idea of the unstoppable movement of the motherland, expresses a dream about its future and the hope for the emergence of real “virtuous people” who are capable of saving the country.

Gogol's poem "Dead Souls" is one of the best works of world literature. The writer worked on the creation of this poem for 17 years, but never completed his plan. "Dead Souls" is the result of many years of Gogol's observations and reflections on human destinies, the fate of Russia.

The title of the work - "Dead Souls" - contains its main meaning. This poem describes both the dead revision souls of the serfs and the dead souls of the landowners, buried under the insignificant interests of life. But it is interesting that the first, formally dead, souls turn out to be more alive than the breathing and talking landowners.

Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov, carrying out his brilliant scam, visits the estates of the provincial nobility. This gives us the opportunity to see the “living dead” “in all its glory.”

The first person Chichikov pays a visit to is the landowner Manilov. Behind the outward pleasantness, even sweetness of this gentleman, lies meaningless daydreaming, inactivity, idle talk, false love for family and peasants. Manilov considers himself well-mannered, noble, educated. But what do we see when we look into his office? A dusty book that has been open on the same page for two years.

There is always something missing in Manilov's house. Thus, in the office only part of the furniture is covered with silk, and two chairs are covered with matting. The farm is managed by a “skillful” clerk who ruins both Manilov and his peasants. This landowner is characterized by idle daydreaming, inactivity, limited mental abilities and life interests. And this despite the fact that Manilov seems to be an intelligent and cultured person.

The second estate that Chichikov visited was the estate of the landowner Korobochka. This is also a "dead soul". This woman's callousness lies in her amazingly petty interests in life. Apart from the prices of hemp and honey, Korobochka doesn’t care about much. Even in the sale of dead souls, the landowner is only afraid of selling herself too cheap. Everything that goes beyond her meager interests simply does not exist. She tells Chichikov that she doesn’t know any Sobakevich, and, therefore, he doesn’t exist in the world.

While searching for the landowner Sobakevich, Chichikov runs into Nozdrev. Gogol writes about this “merry fellow” that he was gifted with all possible “enthusiasm.” At first glance, Nozdryov seems to be a lively and active person, but in reality he turns out to be completely empty. His amazing energy is directed only to carousing and senseless extravagance. Added to this is a passion for lying. But the lowest and most disgusting thing about this hero is “the passion to spoil his neighbor.” This is the type of people “who will start with satin and end with shit.” But Nozdryov, one of the few landowners, even evokes sympathy and pity. It’s just a pity that he directs his indomitable energy and love of life into an “empty” channel.

The next landowner on Chichikov's path finally turns out to be Sobakevich. He seemed to Pavel Ivanovich “very similar to a medium-sized bear.” Sobakevich is a kind of “fist” whom nature “simply chopped with all its might.” Everything in the appearance of the hero and his house is thorough, detailed and large-scale. The furniture in a landowner's house is as heavy as the owner. Each of Sobakevich’s objects seems to say: “And I, too, Sobakevich!”

Sobakevich is a zealous owner, he is prudent and prosperous. But he does everything only for himself, only in the name of his interests. For their sake, Sobakevich will commit any fraud or other crime. All his talent went only into the material, completely forgetting about the soul.

The gallery of landowner “dead souls” is completed by Plyushkin, whose soullessness has taken on completely inhuman forms. Gogol tells us the background story of this hero. Once upon a time, Plyushkin was an enterprising and hardworking owner. Neighbors came to him to learn “stingy wisdom.” But after the death of his wife, the hero’s suspicion and stinginess increased to the highest degree.

This landowner has accumulated huge reserves of “goods”. Such reserves would be enough for several lives. But he, not content with this, walks around his village every day and collects all kinds of garbage, which he puts in his room. Senseless hoarding led Plyushkin to the point that he himself feeds on scraps, and his peasants “die like flies” or run away.

The gallery of “dead souls” in the poem is continued by the images of officials of the city of N. Gogol portrays them as a single faceless mass, mired in bribes and corruption. Sobakevich gives the officials an angry, but very exact description: “The swindler sits on the swindler and drives the swindler.” Officials mess around, cheat, steal, offend the weak and tremble before the strong.

At the news of the appointment of a new governor-general, the inspector of the medical board thinks feverishly about the patients who have died in significant numbers from fever, against which proper measures were not taken. The Chairman of the House turns pale at the thought that he has made a deed for the dead peasant souls. And the prosecutor actually came home and suddenly died. What sins were behind his soul that he was so afraid? Gogol shows us that the life of officials is empty and meaningless. They are simply air smokers who have wasted their precious lives on meanness and fraud.

Next to the “dead souls” in the poem there are bright images of ordinary people who are the embodiment of the ideals of spirituality, courage, love of freedom, and talent. These are images of dead and runaway peasants, primarily Sobakevich’s men: the miracle master Mikheev, the shoemaker Maxim Telyatnikov, the hero Stepan Probka, the skilled stove maker Milushkin. This is also the fugitive Abakum Fyrov, the peasants of the rebel villages of Vshivaya-arrogance, Borovki and Zadirailova.

It was the people, according to Gogol, who retained in themselves " living soul", national and human identity. Therefore, it is with the people that he connects the future of Russia. The writer planned to write about this in the continuation of his work. But he could not, did not have time. We can only guess about his thoughts.

Having begun work on “Dead Souls,” Gogol wrote about his work: “All of Rus' will appear in it.” The writer most carefully studied the past of the Russian people - from its very origins - and the results of this work formed the basis of his work, written in a living, poetic form. Gogol did not work on any of his works, including the comedy “The Inspector General,” with such faith in his calling as a citizen writer with which he created “Dead Souls.” He did not devote so much deep creative thought, time and hard work to any other work of his.

The main theme of the poem-novel is the theme of the present and future fate of Russia, its present and future. Passionately believing in a better future for Russia, Gogol mercilessly debunked the “masters of life” who considered themselves bearers of high historical wisdom and creators of spiritual values. The images drawn by the writer indicate the exact opposite: the heroes of the poem are not only insignificant, they are the embodiment of moral ugliness.

The plot of the poem is quite simple: its main character, Chichikov, a born swindler and dirty entrepreneur, opens up the possibility profitable deals with dead souls, that is, with those serfs who had already gone to another world, but were still counted among the living. He decides to buy dead souls cheaply and for this purpose goes to one of the county towns. As a result, readers are presented with a whole gallery of images of landowners, whom Chichikov visits in order to bring his plan to life. The storyline of the work - the purchase and sale of dead souls - allowed the writer not only to show unusually clearly inner world characters, but also to characterize their typical features, the spirit of the era. Gogol opens this gallery of portraits of local owners with the image of a hero who, at first glance, seems to be quite an attractive person. What is most striking about Manilov’s appearance is his “agreeableness” and his desire to please everyone. Manilov himself, this “very courteous and courteous landowner,” admires and is proud of his manners and considers himself an extremely spiritual and educated person. However, during his conversation with Chichikov, it becomes clear that this man’s involvement in culture is just an appearance, the pleasantness of his manners smacks of cloying, and behind the flowery phrases there is nothing but stupidity. The entire lifestyle of Manilov and his family smacks of vulgar sentimentality. Manilov himself lives in the space he created. illusory world. He has idyllic ideas about people: no matter who he talked about, everyone came out very pleasant, “most amiable” and excellent. From the very first meeting, Chichikov won the sympathy and love of Manilov: he immediately began to consider him his invaluable friend and dream of how the sovereign, having learned about their friendship, would honor them as generals. Life in Manilov’s view is complete and perfect harmony. He doesn’t want to see anything unpleasant in her and replaces knowledge of life with empty fantasies. A wide variety of projects arise in his imagination that will never be realized. Moreover, they arise not at all because Manilov strives to create something, but because fantasy itself gives him pleasure. He is carried away only by the play of his imagination, but for any real action he is completely incapable. It was not difficult for Chichikov to convince Manilov of the benefits of his enterprise: he just had to say that this was being done in the public interest and was fully consistent with “the future vision of Russia,” since Manilov considers himself a person guarding public well-being.

From Manilov, Chichikov heads to Korobochka, who, perhaps, is the complete opposite of the previous hero. Unlike Manilov, Korobochka is characterized by the absence of any claims to higher culture and some kind of “simplicity”. The lack of “showiness” is emphasized by Gogol even in the portrait of Korobochka: she has too unattractive, shabby appearance. Korobochka’s “simplicity” is also reflected in her relationships with people. “Oh, my father,” she turns to Chichikov, “you’re like a hog, your whole back and side are covered in mud!” All Korobochka’s thoughts and desires are focused around the economic strengthening of her estate and continuous accumulation. She is not an inactive dreamer, like Manilov, but a sober acquirer, always poking around her home. But Korobochka’s thriftiness precisely reveals her inner insignificance. Acquisitive impulses and aspirations fill Korobochka’s entire consciousness, leaving no room for any other feelings. She strives to benefit from everything, from household trifles to the profitable sale of serfs, who are for her, first of all, property, which she has the right to dispose of as she pleases. It is much more difficult for Chichikov to come to an agreement with her: she is indifferent to any of his arguments, since the main thing for her is to benefit herself. It’s not for nothing that Chichikov calls Korobochka “club-headed”: this epithet very aptly characterizes her. The combination of a secluded lifestyle with crude acquisitiveness determines Korobochka’s extreme spiritual poverty.

Next is another contrast: from Korobochka to Nozdryov. In contrast to the petty and selfish Korobochka, Nozdryov is distinguished by his violent prowess and “broad” scope of nature. He is extremely active, mobile and perky. Without hesitation for a moment, Nozdryov is ready to do any Business, that is, everything that for some reason comes to his mind: “At that very moment he offered you to go anywhere, even to the ends of the world, to enter into any enterprise you want, exchange whatever you have for whatever you want." Nozdryov’s energy is devoid of any purpose. He easily starts and abandons any of his undertakings, immediately forgetting about it. His ideal is people who live noisily and cheerfully, without burdening themselves with any everyday worries. Wherever Nozdryov appears, chaos breaks out and scandals arise. Boasting and lying are the main character traits of Nozdryov. He is inexhaustible in his lies, which have become so organic for him that he lies without even feeling any need to do so. He is on friendly terms with all his acquaintances, is on friendly terms with them, considers everyone his friend, but never remains true to his words or relationships. After all, it is he who subsequently debunks his “friend” Chichikov in front of provincial society.

Sobakevich is one of those people who stands firmly on the ground and soberly evaluates both life and people. When necessary, Sobakevich knows how to act and achieve what he wants. Characterizing Sobakevich’s everyday way of life, Gogol emphasizes that everything here “was stubborn, without shaking.” Solidity, strength - distinctive features both Sobakevich himself and the everyday environment around him. However, the physical strength of both Sobakevich and his way of life combined with some kind of ugly clumsiness. Sobakevich looks like a bear, and this comparison is not only external: the animal nature predominates in the nature of Sobakevich, who has no spiritual needs. In his firm belief, the only important thing can be taking care of one’s own existence. The saturation of the stomach determines the content and meaning of its life. He considers enlightenment not only an unnecessary, but also a harmful invention: “They interpret it as enlightenment, enlightenment, but this enlightenment is bullshit! I would say another word, but just now it’s indecent at the table.” Sobakevich is prudent and practical, but, unlike Korobochka, he understands well environment, knows people. This is a cunning and arrogant businessman, and Chichikov had quite a difficult time dealing with him. Before he had time to utter a word about the purchase, Sobakevich had already offered him a deal with dead souls, and he charged such a price as if it was a question of selling real serfs.

Practical acumen distinguishes Sobakevich from other landowners depicted in Dead Souls. He knows how to get settled in life, but it is in this capacity that his base feelings and aspirations manifest themselves with particular force.

All the landowners, so vividly and ruthlessly shown by Gogol, as well as the central character of the poem, are living people. But can you say that about them? Can their souls be called alive? Didn’t their vices and base motives kill everything human in them? The change of images from Manilov to Plyushkin reveals an ever-increasing spiritual impoverishment, an ever-increasing moral decline of the owners of serf souls. By calling his work “Dead Souls,” Gogol meant not only the dead serfs whom Chichikov was chasing, but also all the living heroes of the poem who had long since become dead.

At the beginning of work on the poem N.V. Gogol wrote to V.A. Zhukovsky: “What a huge, what an original plot! What a diverse bunch! All of Rus' will appear in it.” This is how Gogol himself determined the scope of his work - all of Rus'. And the writer was able to show in full both the negative and positive aspects of life in Russia of that era. Gogol’s plan was grandiose: like Dante, to depict Chichikov’s path first in “hell” - Volume I of Dead Souls, then “in purgatory” - Volume II of Dead Souls and “in heaven” - Volume III. But this plan was not fully realized; only Volume I, in which Gogol shows the negative aspects of Russian life, reached the reader in full.

In Korobochka, Gogol presents us with a different type of Russian landowner. Thrifty, hospitable, hospitable, she suddenly becomes a “club-head” in the scene of selling dead souls, afraid of selling herself short. This is the type of person with his own mind. In Nozdryov, Gogol showed a different form of decomposition of the nobility. The writer shows us two essences of Nozdryov: first, he is an open, daring, direct face. But then you have to be convinced that Nozdryov’s sociability is an indifferent familiarity with everyone he meets and crosses, his liveliness is an inability to concentrate on any serious subject or matter, his energy is a waste of energy in revelries and debauchery. His main passion, in the words of the writer himself, is “to spoil your neighbor, sometimes for no reason at all.”

Sobakevich is akin to Korobochka. He, like her, is a hoarder. Only, unlike Korobochka, he is a smart and cunning hoarder. He manages to deceive Chichikov himself. Sobakevich is rude, cynical, uncouth; No wonder he is compared to an animal (a bear). By this Gogol emphasizes the degree of savagery of man, the degree of death of his soul. This gallery of “dead souls” is completed by the “hole in humanity” Plyushkin. It's eternal in classical literature image of a stingy person. Plyushkin is an extreme degree of economic, social and moral decay of the human personality.

Provincial officials also join the gallery of landowners who are essentially “dead souls.”

Who can we call living souls in the poem, and do they even exist? I think Gogol did not intend to contrast the suffocating atmosphere of the life of officials and landowners with the life of the peasantry. On the pages of the poem, the peasants are depicted far from rosy. The footman Petrushka sleeps without undressing and “always carries with him some special smell.” The coachman Selifan is not a fool to drink. But it is precisely for the peasants that Gogol has kind words and a warm intonation when he speaks, for example, about Pyotr Neumyvay-Koryto, Ivan Koleso, Stepan Probka, and the resourceful peasant Eremey Sorokoplekhin. These are all the people whose fate the author thought about and asked the question: “What have you, my dear ones, done in your lifetime? How have you gotten by?”

But there is at least something bright in Rus' that cannot be corroded under any circumstances; there are people who constitute the “salt of the earth.” Did Gogol himself, this genius of satire and singer of the beauty of Rus', come from somewhere? Eat! It must be! Gogol believes in this, and therefore at the end of the poem appears artistic image Rus'-troika, rushing into a future in which there will be no Nozdrevs, Plyushkins. A bird or three rushes forward. “Rus', where are you going? Give me an answer. He doesn’t give an answer.”

Griboyedov Pushkin literary plot

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol is a great writer who deeply understood and perceived the culture and history of Russia and Ukraine, a man with a truly Christian philosophy. His early years passed in the atmosphere of Little Russian life, both lordly and peasant, which later became the root of Gogol’s later Little Russian stories and his ethnographic interests. Even in his youth, the writer realized the importance of serving society and his country, he strove to benefit the state as a whole through his actions, so he was disgusted by the selfishness of narrow-minded, self-satisfied people who did not set such goals for themselves. After the success of Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka, Gogol decided to leave his post as an official and continue to serve Russia as a writer. According to Gogol, a writer must lead a person to the truth, to the light, to be a prophet who opens people's eyes, which is what he himself strived for.

The plot of the poem “Dead Souls” was presented to Gogol by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, which Gogol mentions in “The Author’s Confession,” a work containing reflections on his own author’s path and what a writer should be (and he says that he took up this plot with reluctantly). At first, the poem “Dead Souls” was conceived as a satirical novel, but over time the plan expanded more and more. If in The Inspector General the author wanted to “lump everything bad that is in Rus' into a heap and laugh at everything at once,” then in the first volume of Dead Souls he sought to “show all of Rus' from one side,” and on the negative side. Gogol was always concerned about the problem of spiritual degradation of man; he was skeptical about the moral state of his contemporary society, in which corruption and veneration flourish, no one worries about highest values being. To emphasize the essence of these reflections, the planned three volumes of the poem drew a clear analogy with “ Divine Comedy"Dante Alighieri - the first volume symbolized "Hell", it clearly showed negative characters on the path of gradual mental death. The second volume was supposed to serve as “Purgatory”, and in the third volume “Paradise” was supposed to come - the heroes mentioned in the first volume were supposed to come to spiritual enlightenment. Since the author was a man with a truly Christian worldview, he believed that even the most inert person who had forgotten true meaning existence, did not lose the chance of salvation. Therefore, the key should have been the transformation of Plyushkin, the most deadened of all the characters in the poem.

The characters of the landowners in “Dead Souls” make up the so-called “gallery of eternal types.” The author more than once emphasizes in the lyrical digressions of the poem that a character like Manilov or Sobakevich can be found anywhere - he can live in another era, in another country, have a completely different title, upbringing, but the essence will always be the same. Built on the alternation of “spendthrift-accumulator”, the images of landowners emphasize Gogol’s idea that throughout life a person is forced to fight for his place in the sun, thus replacing true goals with false ones. In this case, the “axis of rotation” of all the characters becomes money, self-interest - a striking example is the economic Korobochka, who is always afraid to sell herself cheap, who gave away Chichikov’s plan, asking “how much are dead souls these days.” The complete collapse of intangible values is the negative side of Russia, which the author wanted to make “sideways”, because this problem worried him very much, and he believed that after reading the poem, a person would think, try to compare his friends or himself with “dead souls” " Only after being horrified by the resemblance to these characters does a person get the opportunity to analyze his life and his actions, and try to change for the better.

The image of Chichikov is a very important aspect of the author’s thinking about human nature. He is important not only because during his journey we see all of Rus' from the brilliant, ceremonial Petersburg to the seedy, God-forsaken villages. The journey should also show the process inner evolution Chichikova. The purpose of his scam reflects the main idea of the poem - the purchase of souls dead peasants, although indicated only on paper, is really feasible only in a country that is deeply mired in corruption. From the point of view of Gogol’s philosophy, its plan is immoral and does not correspond to the ideals of the Christian worldview - the purchase of the soul, as an eternal element of being, an immortal essence, is absolutely cynical, especially if such an act is against religious foundations committed out of self-interest. This begs the question: how did it happen that man descended to such a level? shameful act? We find the answer in the biography of the main character - early left to the mercy of fate, young Chichikov sacredly honored his father’s behest to be sensitive to every penny and tirelessly increase his fortune (this, among other things, is condemned by Gogol - thus, Chichikov is similar to the landowners). While still at school, Pasha Chichikov began to carry out his first speculations, based, like all subsequent ones, on a perfect knowledge of human nature. He bought children's breakfasts for pennies, and subsequently resold them to them - in this case, he even used such a natural feeling as hunger. In the same way, it will hit the weak spot of the landowners - the thirst for profit. Pavel Andreevich knew very well that a very rare landowner would refuse to get rid of serfs who were dead and did not bring any benefit, but for whom they had to pay a tax, and even receive money for it.

Chichikov is a person endowed from birth with such wonderful benefits as perseverance and intelligence, which he uses for evil, for the sake of accumulation. Having found himself in a good position, he immediately begins to take bribes (which, as the author emphasizes, was considered a completely understandable thing), and provides himself with a stable income. Despite the fact that they find out about this and he is fired, he does not lose his presence of mind.

Gogol believed that there is Providence - God's will, which is trying to guide the right path a person who has veered down the path of deception, fraud and other signs of moral decline. Chichikov's many failures indicate that he does not listen to Providence - as a result, according to the plan of the poem, once in prison, Chichikov was supposed to “see the light.” Gogol bitterly says that he finds in himself the traits of all his characters, including Chichikov, so he calls not to lose those qualities that are inherent in man from the very beginning.

The image of Russia inextricably follows the main theme - reflections on man, since the appearance of the country depends on the people inhabiting it and the ruling force of the state, in this case in the form of a corrupt bureaucracy. Therefore, it is worth talking separately, both about the Russian spirit and about the images of officials.

Officials of the “Dead Souls” have much in common with the officials of the “Inspector General” - they share the same qualities. Since the poem shows Rus' only from one side, all officials are negative and their characters are typified. They are characterized by a spirit of nepotism, mutual responsibility - the bribes that they constantly take are not considered a vice. At the same time, everyone knows that not a single business can be arranged “if you don’t butter it up” and everyone perceives this as a completely natural fact. The souls of officials are just as dead - they are not interested in anything and eke out a meaningless existence due to their stupidity and ignorance. Year after year they go to the same balls, play whist, and, moreover, violate the commandment that says that one cannot judge a person by endlessly spreading dirty rumors and gossip.

The author brings us to the conclusion that such a situation is impossible in any civilized country - how can you love an official who constantly takes bribes for allegedly “not being proud”? We again come to the conclusion that Gogol put above all else a person’s duty to his Fatherland and its people, which the officials completely forgot about.

"There's only one there honest man: prosecutor; and he, to tell the truth, is a pig,” says a quote from the poem, which very accurately sums up the conversation about the situation that has developed in provincial town N.

Of course, thinking about the fate of Russia cannot do without thinking about the essence of the Russian people. Russian soul, so incomprehensible to a foreign person, in fact, resembles a road - just as wide, simple, immense; and the phrase “what Russian doesn’t like driving fast!” has a direct relation to this image. Gogol is not inclined to idealize the Russian mentality, so on the very first page he describes two peasants standing on the side of the road and discussing whether Chichikov’s chaise will reach Moscow or Kazan, which does not concern them at all. This expresses the senseless contemplation that, to one degree or another, is inherent in every Russian. The author also condemns the voiceless submission with which the coachman Selifan agrees that he needs to be flogged, without at all resisting the punishment. Russian people are always curious, like peasants who abandoned all their work to see how two carriages collided.

Nevertheless, a Russian person is talented and hardworking, although he treats most things lightly and with some laziness. Especially mentioned is the accuracy with which the Russian person expresses himself: “It is expressed strongly Russian people! And if he rewards someone with a word, then it will go to him and his descendants.”

In conclusion, I want to say that the problems that Gogol discusses are still relevant. In our time we can talk about the same deadness human soul, despite the many historical upheavals and changes that have occurred since the writing of the poem, if not the deterioration of the situation due to the imposed material value system. Officials take bribes in the same way and do not care about their main function - caring for the people. And, of course, the Russian spirit itself, which is an unchangeable constant, has not changed at all. “Dead Souls” is a magnificent work, one of the main decorations of Russian literature, written not only by a great writer, but also by a great philosopher who was not afraid to set such lofty and immense goals for himself.