How Oblomov’s appearance and his surroundings are depicted. Artistic Features

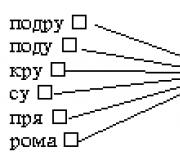

Essay plan

1. Introduction. Goncharov's style

2. Main part. Portraiture in the novel “Oblomov”

— Portrait-sketch of Oblomov in the novel

— Interior as an integral part of the hero’s portrait

— The motif of immobility in the description of Oblomov’s appearance. Philosophical subtext of the topic

— Portrait of Stolz in the novel

— The motive of the statue and its meaning in the portrait of Olga Ilyinskaya

— Author's impression.

— Description of the heroine’s appearance in dynamics.

— The device of psychological parallelism in the portrait of Olga.

— The motif of peace in the description of Olga Ilyinskaya’s appearance.

— Portrait of Agafya Pshenitsyna in the novel.

— Portrait of Tarantiev in the novel.

— The meaning of a detailed description of the hero’s appearance.

— Fragmentary portraits in the novel.

3. Conclusion. Functions of portraits in Goncharov’s novel.

I.A. appears before us as a master of portraiture. His portraits are flexible, detailed, detailed. The portrait includes a description of the hero’s appearance, a description of his clothing, his surroundings, and incidental author’s remarks, and characterization, and landscapes, and the perception of other characters. In a word, in Goncharov we have a detailed portrait-essay. And in this the creative style of the writer is close to the creative style of N.V. Gogol.

Let's try to look at the portraits in Goncharov's novel. We find the first description of appearance already at the beginning of the work. This is a detailed portrait of Oblomov. In this description, Goncharov records the first impression and immediately gives a hint that not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance, that this portrait has its own subtext. There is some uncertainty and vagueness in the very description of the hero’s appearance. At the same time, critics noted that the muted tones here are in harmony with the colors of the landscape of the Central Russian strip (“Oblomov’s Dream”): “He was a man about thirty-two or three years old, of average height, pleasant appearance, with dark gray eyes, but with a lack of any definite idea, any concentration in facial features. The thought walked like a free bird across the face, fluttered in the eyes, sat on half-open lips, hid in the folds of the forehead, then completely disappeared, and then an even light of carelessness glowed throughout the whole body. From the face, carelessness passed into the poses of the whole body, even into the folds of the dressing gown.” And then we read: “Ilya Ilyich’s complexion was neither ruddy, nor dark, nor positively pale, but indifferent or seemed so, perhaps because Oblomov was somehow flabby beyond his years...” This portrait reveals to us the inner qualities of the hero, his habits: laziness, passive attitude towards life, his lack of any serious interests. Nothing occupies Oblomov, he has no habit of either mental or physical labor. The leitmotif of the entire description is softness. In the face of Ilya Ilyich - “the gentleness that was the dominant and main expression,” and this gentleness was an expression not only of the face, “but of the whole soul.” The same “softness” is in the hero’s movements, his oriental robe is “soft,” and his feet have “soft and wide” shoes.

In describing Oblomov’s body, Goncharov emphasizes the hero’s sedentary lifestyle, sybaritism, and lordly effeminacy: “In general, his body, judging by the matte, overly white color of his neck, small plump arms, soft shoulders, seemed too effeminate for a man.” Here the writer denotes the hero’s habits - “lying down”, love of loose clothing. Oblomov's home suit (oriental robe) becomes a symbol of his sedentary, measured life. It is characteristic that Oblomov throws away his robe at the time when he falls in love with Olga. Agafya Pshenitsyna takes it out and returns it to the owner.

Goncharov’s interior is, as it were, a continuation of the portrait: the room only at first glance seems “beautifully decorated.” But the “experienced eye” notes the ungraceful chairs, the unsteadiness of the shelves, the sagging back of the sofa. There are cobwebs scattered across the walls, the mirrors are covered with dust, the carpets are “stained”, there is always a plate left over from dinner on the table, a forgotten towel is lying on the sofa. The motif of sleep, deadness, and fossilization already appears in this interior. Describing the room, Goncharov notes: “one would think that no one lives here - everything was so dusty, faded and generally devoid of living traces of human presence.”

The motif of fossilization and immobility also appears directly in the description of the hero’s appearance. Goncharov notes that “neither fatigue nor boredom” could drive a certain expression from Oblomov’s face, the thought “hid in the folds of his forehead, then completely disappeared,” anxiety also could not take over his entire being - “all anxiety was resolved with a sigh and died away in apathy or in a drowsiness." And in this some researchers already find deep philosophical implications. As Weil and Genis note, “these frozen, petrified “folds” suggest an analogy with an ancient statue. The comparison is fundamentally important, which Goncharov consistently makes throughout the novel. In Oblomov’s figure, the golden ratio is observed, which gives a feeling of lightness, harmony and completeness to ancient sculpture. Oblomov’s stillness is graceful in its monumentality, it is endowed with a certain meaning.” The hero becomes funny, clumsy, awkward precisely in movement, in comparison with Stolz and Olga. In the house of Agafya Pshenitsyna, on the Vyborg side, in this “small Oblomovka”, he again turns into a statue: “He will sit, cross his legs, rest his head on his hand - he does all this so freely, calmly and beautifully... he is all so good , is so pure that he can do nothing, and does not.” What is the meaning of this monumentality of the hero? From the point of view of Stolz and Olga, who cannot imagine their life without movement, Oblomov lives without a goal. He is dead while alive. According to Oblomov himself, the border between life and death is conditional, it is rather a kind of intermediate state - a dream, a dream, Oblomovka. He ends up being the only genuine person in the novel. Researchers compare Olga and Stolz to machines, each of which has its own gear to engage with others. Oblomov is a complete, perfect statue. But this is precisely where the tragic paradox lies. Other heroes - “only fragments of Oblomov’s whole personality - are alive due to their imperfection, their incompleteness.” Oblomov is dead, he cannot exist in harmony with the world around him due to his perfection, harmony, and self-sufficiency. Thus, Goncharov’s portrait of the hero is included in the philosophical problematics of the novel.

The portrait of Stolz in the novel is given in contrast to the portrait of Oblomov. And this contrast is in the definiteness, clarity of lines and colors. “He is all made up of bones, muscles and nerves, like a blooded English horse. He is thin; he has almost no cheeks at all, that is, bone and muscle, but no sign of fatty roundness; complexion is even, darkish and no blush; the eyes, although a little greenish, are expressive.” The leitmotif of this portrait is movement. Stolz is pragmatic, businesslike: he serves, takes care of business, participates “in some company.” “He is constantly on the move: if society needs to send an agent to Belgium or England, they send him; you need to write some project or adapt a new idea to business - they choose it. Meanwhile, he goes out into the world and reads: when he has time, God knows.” In the image of Stolz, the writer emphasizes rationalism, the mental principle: “it seems that he controlled both sorrows and joys with the movement of his hands,” “he opened his umbrella while it was raining,” “suffered while the sorrow lasted,” “enjoyed joy as if plucked along the way.” flower." Most of all, Stolz was afraid of “imagination,” “every dream.” Thus, Stolz is presented in the novel not only as the external antipode of Oblomov, but also his antipode in his internal qualities.

The motif of the statue is heard in Goncharov and in the description of Olga Ilyinskaya. It is characteristic that she appears this way precisely in the imagination of Oblomov, who cannot forget her image after meeting her. “Olga in the strict sense was not a beauty, that is, there was no whiteness in her, no bright coloring of her cheeks and lips, and her eyes did not burn with rays of inner fire; there were no corals on the lips, no pearls in the mouth, no miniature hands, like those of a five-year-old child, with fingers shaped like grapes.

But if she were turned into a statue, she would be a statue of grace and harmony. The size of the head strictly corresponded to a somewhat tall stature; the size of the head corresponded to the oval and size of the face; all this, in turn, was in harmony with the shoulders, and the shoulders with the body...” However, this immobility here symbolizes not perfection and completeness (as in Oblomov’s portrait), but rather the “sleeping”, not yet awakened soul of the heroine.

Next we see a portrait of her, given in the author’s perception. And here what Oblomov does not notice is emphasized - the predominance of the rational principle. Goncharov here seems to give us an outsider’s view: “Whoever met her, even absent-minded, stopped for a moment in front of this so strictly and deliberately artistically created creature.

The nose formed a slightly noticeably convex, graceful line; the lips are thin and mostly compressed: a sign of a thought constantly directed at something. The same presence of a speaking thought shone in the vigilant, always cheerful, never-missing gaze of dark, gray-blue eyes. The eyebrows gave special beauty to the eyes: they were not arched, they did not round the eyes with two thin strings plucked with a finger - no, they were two light brown, fluffy, almost straight stripes, which rarely lay symmetrically: one was a line higher than the other, hence above the eyebrow there was a small fold in which something seemed to say, as if a thought rested there. Olga walked with her head tilted slightly forward, resting so slenderly and nobly on her thin, proud neck; she moved her whole body evenly, walking lightly, almost imperceptibly..."

The writer gives a dynamic portrait of the heroine, depicting her at certain moments in her life. This is how Olga appears in moments of singing: “Her cheeks and ears were red with excitement; sometimes a play of heart lightning would suddenly sparkle on her fresh face, a ray of such mature passion would flare up, as if she were experiencing a distant future time of life in her heart, and suddenly this instant ray would go out again, again her voice would sound fresh and silvery.” The author uses a comparison with natural phenomena, describing the “awakening of the heroine’s soul” when she understands Oblomov’s feelings: “... her face was gradually filled with consciousness; a ray of thought, guesswork made its way into every feature, and suddenly the whole face was illuminated with consciousness... The sun also sometimes, coming out from behind a cloud, little by little illuminates one bush, another, the roof, and suddenly bathes the whole landscape in light...” In Oblomov’s perception, Olga is given to us in that moment when her feeling is just emerging and Ilya is afraid to frighten him away. “A young, naive, almost childish smile never appeared on her lips, she never looked so wide, openly with her eyes when they expressed either a question, or bewilderment, or simple-minded curiosity, as if she had nothing to ask, there is nothing to know, nothing to be surprised at!

Her gaze did not follow him as before. She looked at him as if she had known him for a long time, studied him, finally, as if he was nothing to her, just like a baron...

There was no sternness, no yesterday's annoyance, she joked and even laughed, answered questions in detail, to which she would not have answered anything before. It was clear that she had decided to force herself to do what others were doing, which she had not done before. The freedom, the ease that allowed her to express everything that was on her mind, was no longer there. Where did everything suddenly go?” Here Ilya Ilyich analyzes Olga’s mood and feelings.

But Olga realizes her power over him, she takes on the role of a “guiding star.” And again the description of her appearance is given here in the perception of Ilya. Goncharov here does not give us a new portrait of the heroine, but uses the technique of psychological parallelism, reminding the reader of her already known features: “Her face was different, not the same one when they walked here, but the one with which he left her for the last time and which gave him such anxiety. And the caress was somehow restrained, the whole facial expression was so concentrated, so definite; he saw that it was impossible to play with guesses, hints and naive questions with her, that this childish, cheerful moment would be survived.”

The author also denotes Olga’s inner qualities, inserting subtle remarks, conveying Stolz’s impressions and the perception of her by secular society. In these descriptions, Goncharov emphasizes the simplicity and naturalness of the heroine. “Be that as it may, in a rare girl you will find such simplicity and natural freedom of look, word, and action. You’ll never read in her eyes: “Now I’ll purse my lip a little and think - I’m so pretty. I’ll look there and get scared, I’ll scream a little, and now they’ll run up to me. I’ll sit by the piano and stick out the tip of my leg a little...”

No affectation, no coquetry, no lies, no tinsel, no intent! For all of this, almost only Stolz appreciated her; for this, she sat through more than one mazurka alone...

Some considered her simple, short-sighted, because neither wise maxims about life, about love, nor quick, unexpected and bold remarks, nor read or overheard judgments about music and literature poured from her tongue: she spoke little, and only her own, unimportant - and smart and lively “gentlemen” walked around her; the quiet ones, on the contrary, considered her too sophisticated and were a little afraid.”

In the last part of the novel, as M.G. notes. Urtmintsev, in Olga’s portrait the motif of peace sounds twice. She finds happiness with the rational, reserved Stolz. “She fixed her eyes on the lake, on the distance, and thought so quietly, so deeply, as if she had fallen asleep. She wanted to catch what she was thinking, what she was feeling, but she couldn’t. Thoughts rushed as smoothly as waves, blood flowed so smoothly in my veins. She experienced happiness and could not determine where the boundaries were, what it was. She thought why she felt so quiet, peaceful, inviolably good, why she was at peace...” And at the end of the chapter we read: “She still sat as if she were sleeping - the sleep of her happiness was so quiet: she did not move, almost did not breathe.” The motif of peace here denotes a certain limitation of the heroine, the only possible life option for her.

In contrast to the poetic portrait of Olga, the novel gives a “prosaically everyday” portrait of Agafya Pshenitsyna. Here Goncharov only indicates the appearance features, describes the clothes, but says nothing about the habits, manners, and character traits of this heroine. “She was about thirty. She was very white and full in the face, so that the blush, it seemed, could not break through her cheeks. She had almost no eyebrows at all, but in their place there were two slightly swollen, shiny stripes with sparse blond hair. The eyes are grayish-simple, like the whole facial expression; the hands are white, but hard, with large knots of blue veins protruding outward.

The dress fit her tightly: it is clear that she did not resort to any art, not even an extra skirt, to increase the volume of her hips and reduce her waist. Because of this, even her closed bust, when she was without a headscarf, could serve a painter or sculptor as a model of a strong, healthy breast, without violating her modesty. Her dress, in relation to the elegant shawl and ceremonial cap, seemed old and shabby.” The hands of this heroine reveal her daily habit of work, and indeed in the future she appears as an excellent housewife. To Oblomov she seems modest and shy, we see that she is capable of much for the sake of love. However, Goncharov does not reflect all these qualities in the description of her appearance.

The novel also gives a detailed portrait of Tarantiev, Oblomov's fellow countryman. This is “a man of about forty, belonging to a large breed, tall, bulky in the shoulders and throughout the body, with large facial features, a large head, a strong, short neck, large protruding eyes, thick lips. A quick glance at this man gave rise to the idea of something rough and unkempt. It was clear that he was not chasing the elegance of the suit. It was not always possible to see him clean shaven. But he apparently didn’t care; he was not embarrassed by his suit and wore it with some kind of cynical dignity.” This portrait is also a sketch portrait. Goncharov gives us the life story of the hero, outlines his manners, habits, and character traits. “Tarantiev was a master only of talking; in words he decided everything clearly and easily, especially when it came to others; but as soon as it was necessary to move a finger, to get under way - in a word, to apply the theory he had created to the case and give it a practical move, to show discretion, speed - he was a completely different person: here he was missing ... "

Why is the description of Tarantiev in such detail in Goncharov’s novel? The fact is that this character not only plays an important role in the plot, but is also connected with the problems of the novel. Goncharov brings this hero closer to Oblomov. And this is not only about their common homeland - Oblomovka. Taranyev, just like the main character, develops in the novel the motif of unfulfilled hopes. By the will of fate, Tarantyev, who had received some education, was to remain a scribe for the rest of his life, “and meanwhile he carried within himself and was aware of a dormant force, locked inside him by hostile circumstances forever, without hope of manifestation, as they were locked, according to fairy tales, within the cramped, enchanted walls are the spirits of evil, deprived of the power to harm.” The same “dormant power” is present in Oblomov. Tarantiev is like a “reduced double” of Oblomov, a kind of parody of the main character.

Other descriptions of appearance in the novel are more brief and fragmentary. These are the portraits of Oblomov’s guests at the beginning of the novel - Volkov, Sudbinsky, Penkin, Alekseev. Researchers have noted here the similarity in the descriptions of these characters with the stylistic manner of N.V. Gogol in the poem

Introduction

Goncharov’s novel “Oblomov” is a socio-psychological work of Russian literature of the mid-19th century, in which the author touches on a number of “eternal” topics that are also relevant for the modern reader. One of the leading literary techniques used by Goncharov is the portrait characterization of heroes. Through a detailed description of the appearance of the characters, not only their character is revealed, but also the individual characteristics, similarities and differences of the characters are emphasized. A special place in the narrative is occupied by the portrait of Oblomov in the novel “Oblomov”. It is with a description of Ilya Ilyich’s appearance that the author begins the work, paying special attention to the small details and nuances of the character’s appearance.

Portrait of Ilya Ilyich Oblomov

Ilya Ilyich is depicted as a thirty-two-year-old man, of average height with dark gray eyes. He is quite attractive in appearance, but “flattened beyond his years.” The main feature of the hero’s appearance was softness - in facial expression, in movements and body lines. Oblomov did not give the impression of a man living with great goals or constantly thinking about something - in the features of his face one could read the absence of any definite idea and concentration, “thought walked like a free bird across his face, fluttered in his eyes, sat on his half-open lips, hid in the folds of his forehead, then she completely disappeared, and then an even light of carelessness glowed throughout her face. From the face, carelessness passed into the poses of the whole body, even into the folds of the dressing gown.”

Sometimes an expression of boredom or fatigue flashed through his gaze, but they could not drive away from Ilya Ilyich’s face the softness that was present even in his eyes and smile. His too fair skin, small plump hands, soft shoulders and a body too pampered for a man betrayed him as a man not accustomed to work, accustomed to spending all his days in idleness, counting on the help of servants. Any strong emotions were not reflected in Oblomov’s appearance: “when he was even alarmed,” his movements “were also restrained by gentleness and laziness, not without a kind of grace. If a cloud of care came over your face from your soul, your gaze became cloudy, wrinkles appeared on your forehead, and a game of doubt, sadness, and fear began; but rarely did this anxiety congeal in the form of a definite idea, and even more rarely did it turn into an intention. All anxiety was resolved with a sigh and died away in apathy or dormancy.”The portrait of Ilya Ilyich Oblomov allows us to capture the main character traits of the hero: inner softness, complaisance, laziness, complete calmness and even a certain indifference of the character in relation to the world around him, forming a complex and multifaceted personality. Goncharov himself points out the depth of Oblomov’s character at the beginning of the work: “a superficially observant, cold person, looking casually at Oblomov, would say: “He must be a good man, simplicity!” A deeper and prettier person, having peered into his face for a long time, would have walked away in pleasant thought, with a smile.”

The symbolism of clothing in the image of Oblomov

Spending all his days in idleness and all kinds of dreams, making unrealistic plans and drawing in his imagination many pictures of the desired future, Oblomov did not pay attention to his appearance, preferring to wear his favorite home clothes, which seemed to complement his calm facial features and pampered body. He was wearing an old oriental robe with large wide sleeves, made of Persian fabric, in which Ilya Ilyich could wrap himself twice. The robe was devoid of any decorative elements - tassels, velvet, belt - this simplicity, perhaps, was what Oblomov liked most about this element of his wardrobe. It was clear from the robe that the hero had been wearing it for a long time - it “lost its original freshness and in places replaced its primitive, natural gloss with another, acquired one,” although it “still retained the brightness of oriental paint and the strength of the fabric.” Ilya Ilyich liked that the robe was soft, flexible and comfortable - “the body does not feel it on itself.” The second obligatory element of the hero’s home toilet was soft, wide and long shoes “when he, without looking, lowered his feet from the bed to the floor, he certainly fell into them immediately.” Ilya Ilyich did not wear a vest or tie at home, as he loved freedom and space.

The description of Oblomov’s appearance in his home decoration paints before the readers the image of a provincial gentleman who does not need to rush anywhere, because the servants will do everything for him and who spends all his days lounging on his bed. And the things themselves are more like Ilya Ilyich’s faithful servants: the robe, “like an obedient slave,” obeys his every movement, and there was no need to look for shoes or put them on for a long time - they were always at his service.

Oblomov seems to recreate the quiet, measured, “homely” atmosphere of his native Oblomovka, where everything was just for him, and his every whim was fulfilled. The robe and shoes in the novel are symbols of “Oblomovism”, indicating the internal state of the hero, his apathy, detachment from the world, retreat into illusion. Boots become a symbol of real, “uncomfortable” life for Ilya Ilyich: “for whole days,” Oblomov grumbled, putting on a robe, “you don’t take off your boots: your feet itch!” I don’t like this life of yours in St. Petersburg.” However, boots are also a symbol of leaving the power of “Oblomovism”: having fallen in love with Olga, the hero himself throws away his favorite robe and shoes, replacing them with a secular suit and boots that he so dislikes. After parting with Ilyinskaya, Ilya Ilyich becomes completely disillusioned with the real world, so he again takes out an old robe and finally plunges into the swamp of “Oblomovism”.

Appearance of Oblomov and Stolz in Goncharov’s novel

According to the plot of the work, Andrei Ivanovich Stolts is Oblomov’s best friend and his complete antipode both in character and appearance. Stolz was “all made up of bones, muscles and nerves, like a blooded English horse,” “that is, there is bone and muscle, but not a sign of fatty roundness.” Unlike Ilya Ilyich, Andrei Ivanovich is thin, with a darkish, even complexion, greenish, expressive eyes and stingy facial expressions, which he used exactly as much as necessary. Stolz did not have that external softness that was the main feature of his friend; he was characterized by firmness and calmness, without unnecessary fussiness and haste. Everything in his movements was harmonious and controlled: “It seems that he controlled both sorrows and joys, like the movement of his hands, like the steps of his feet, or how he dealt with bad and good weather.”

It would seem that both heroes, Oblomov and Stolz, were distinguished by external calm, but the nature of this calm was different among men. The entire inner storm of Ilya Ilyich’s experiences was lost in his excessive softness, carelessness and infantility. For Stolz, strong experiences were alien: he controlled not only the whole world around him and his movements, but also his feelings, not even allowing them to arise in his soul as something irrational and beyond his control.

conclusions

In “Oblomov”, Goncharov, as a skilled artist, was able to show through the portrait of the characters the full depth of their inner world, “drawing” the characteristics of the characters of the characters, depicting, on the one hand, two social characters typical of that time, and on the other, outlining two complex and tragic images, interesting for their versatility to the modern reader.

Work test

In the novel “Oblomov,” Ivan Goncharov touches on the problem of the formation of a personality who grew up in an environment where they tried in every possible way to infringe on the expression of independence.

The image and characteristics of Oblomov will help the reader understand what people become who are accustomed from childhood to getting what they want with the help of others.

External image of Ilya Ilyich Oblomov

“He was a man about thirty-two or three years old, of average height, with dark gray eyes, of pleasant appearance.”

It was difficult to discern certain emotions on the man’s face. Thoughts wandered around him, but disappeared too quickly, reminiscent of birds.

Ilya Ilyich Oblomov was full. Small, plump arms, narrow shoulders, and a pale neck indicated excessive delicacy. In his youth, the master was distinguished by his slimness. The girls liked the handsome blond man. Now he's gone bald. Andrei Stolts advises his friend to lose weight, arguing that it makes him sleepy. When visiting Oblomov’s apartment, he often sees that the master is sleeping on the move, looking for any excuse to lie down on the sofa. And swelling makes it clear that your health is bad. The reason could be the kilograms gained.

Rising from the bed, Oblomov groans like an old man. He calls himself:

“a shabby, worn out, flabby caftan.”

Recently, Ilya Ilyich attended all sorts of social events. Soon going out into the world began to depress him. Traveling with guests required a neat appearance, but he was tired of the daily change of shirts and the requirement to be clean-shaven. Taking care of his own appearance seemed to him a “stupid idea.”

His clothes are always sloppy. Bed linen is rarely changed. Servant Zakhar often makes comments to him. Stolz assures us that people haven’t been wearing robes like the ones he wears for a long time. The socks he wears are from different pairs. He could easily have worn his shirt inside out and not noticed.

“Oblomov was always in the house without a tie or vest. He loved space and freedom. The shoes on my feet were wide. When I lowered my legs from the bed, I immediately fell into them.”

Many details of his appearance indicate that Ilya is truly lazy and indulges his own weaknesses.

Housing and life

For about eight years, Ilya Oblomov has been living in a spacious rented apartment in the very center of St. Petersburg. Of the four rooms, only one is used. It serves as his bedroom, dining room, and reception room.

“The room where Ilya lay seemed perfectly decorated. There was a mahogany bureau, two sofas upholstered in expensive fabrics, and luxurious screens with embroidery. There were carpets, curtains, paintings, expensive porcelain figurines.”

Interior items were expensive items. But this did not brighten up the negligence emanating from every corner of the room.

There were a lot of cobwebs on the walls and ceiling. The furniture was covered with a thick layer of dust. After meetings with his beloved Olga Ilyinskaya, he would come home, sit on the sofa, and draw her name in large letters on the dusty table. Various objects were placed on the table. There were dirty plates and towels, last year's newspapers, books with yellowed pages. There are two sofas in Oblomov's room.

Attitude to learning. Education

At the age of thirteen, Ilya was sent to study at a boarding school in Verkhlevo. Learning to read and write did not attract the boy.

“Father and mother put Ilyusha in front of a book. It was worth the loud cries, tears and whims.”

When he had to leave for training, he came to his mother and asked her to stay at home.

“He came to his mother sadly. She knew the reason, and secretly sighed about being separated from her son for a whole week.”

I studied at the university without enthusiasm. I was absolutely not interested in additional information, I read what the teachers asked.

He was content with writing in a notebook.

In the life of student Oblomov there was a passion for poetry. Comrade Andrei Stolts brought him various books from the family library. At first he read them with delight, but soon abandoned them, which was to be expected from him. Ilya managed to graduate from university, but the necessary knowledge was not deposited in his head. When it was necessary to demonstrate his knowledge of law and mathematics, Oblomov failed. I have always believed that education is sent to a person as retribution for sins.

Service

After training, time passed faster.

Oblomov “never made any progress in any field, he continued to stand at the threshold of his own arena.”

Something had to be done, and he decided to go to St. Petersburg to establish himself in the service as a clerical clerk.

At 20, he was quite naive; certain views on life could be attributed to inexperience. The young man was sure that

“The officials formed a friendly, close family, concerned about mutual peace and pleasure.”

He also believed that there was no need to attend services every day.

“Slush, heat or simply a lack of desire can always serve as a legitimate excuse for not going to work. Ilya Ilyich was upset when he saw that he had to be at work strictly adhering to the schedule. I suffered from melancholy, despite the condescending boss.”

After working for two years, I made a serious mistake. When sending an important document, I confused Astrakhan with Arkhangelsk. I didn’t wait for a reprimand. I wrote a report about leaving, but before that I stayed at home, hiding behind my failing health.

After the circumstances that occurred, he made no attempts to return to service. He was glad that he didn’t need it now:

“from nine to three, or from eight to nine, write reports.”

Now he is absolutely sure that work cannot make a person happy.

Relationships with others

Ilya Ilyich seems quiet, absolutely non-conflicting.

“An observant person, glancing briefly at Oblomov, would say: “Good guy, simplicity!”

His communication with his servant Zakhar from the very first chapters can radically change his opinion. He often raises his voice. Lackey really deserves a little shake-up. The master pays him for maintaining order in the apartment. He often puts off cleaning. Finds hundreds of reasons why cleaning is impossible today. There are already bedbugs, cockroaches in the house, and occasionally a mouse runs through. It is for all sorts of violations that the master scolds him.

Guests come to the apartment: Oblomov’s former colleague Sudbinsky, writer Penkin, fellow countryman Tarantiev. Each of those present tells Ilya Ilyich, who is lying in bed, about his eventful life, and is invited to take a walk and unwind. However, he refuses everyone, leaving the house is a burden for him. The master is afraid that it will leak through him. In every sentence he sees a problem and expects a catch.

“Although Oblomov is affectionate with many, he sincerely loves one, trusts him alone, maybe because he grew up and lived with him. This is Andrei Ivanovich Stolts.”

It will become clear that despite his indifference to all kinds of entertainment, Oblomov does not dislike people. They still want to cheer him up and make another attempt to pull him out of his beloved bed.

Living with the widow Pshenitsyna, Ilya takes great pleasure in working with her children, teaching them to read and write. With the aunt of his beloved Olga Ilyinskaya, he easily finds common topics for conversation. All this proves Oblomov’s simplicity, the lack of arrogance, which is inherent in many landowners.

Love

His friend Andrei Stolts will introduce Oblomov to Olga Ilyinskaya. Her piano playing will leave a lasting impression on him. At home, Ilya did not sleep a wink all night. In his thoughts he painted the image of a new acquaintance. I remembered every feature of my face with trepidation. After that, he began to visit the Ilyinsky estate often.

Confessing his love to Olga will plunge her into embarrassment. They haven't seen each other for a long time. Oblomov moves to live in a rented dacha located near his beloved’s house. I just couldn’t control myself enough to visit her again. But fate itself will bring them together, organizing a chance meeting for them.

Inspired by feelings, Oblomov changes for the better.

"He gets up at seven o'clock. There is no fatigue or boredom on the face. Shirts and ties shine like snow. His coat is beautifully tailored.”

Feelings have a positive effect on his self-education. He reads books and doesn't lie idle on the couch. Writes letters to the estate manager with requests and instructions to improve the situation of the estate. Before his relationship with Olga, he always put it off until later. Dreams of family and children.

Olga becomes more and more convinced of his feelings. He carries out all her instructions. However, “Oblomovism” does not let the hero go. Soon it begins to seem to him that he:

“is in Ilyinskaya’s service.”

In his soul there is a struggle between apathy and love. Oblomov believes that it is impossible to feel sympathy for someone like him. “It’s funny to love someone like that, with flabby cheeks and sleepy eyes.”

The girl responds to his guesses with crying and suffering. Seeing the sincerity in her feelings, he regrets what he said. After a while, he again begins to look for a reason to avoid meetings. And when his beloved comes to him, he can’t get enough of her beauty and decides to propose marriage to her. However, the current way of life takes its toll.

Essay plan

1. Introduction. Goncharov's style

2. Main part. Portraiture in the novel “Oblomov”

Portrait-sketch of Oblomov in the novel

Interior as an integral part of the hero's portrait

The motif of immobility in the description of Oblomov’s appearance. Philosophical subtext of the topic

Portrait of Stolz in the novel

The motive of the statue and its meaning in the portrait of Olga Ilyinskaya

Description of the heroine's appearance in dynamics.

The device of psychological parallelism in the portrait of Olga.

The motif of peace in the description of Olga Ilyinskaya’s appearance.

Portrait of Agafya Pshenitsyna in the novel.

Portrait of Tarantiev in the novel.

The meaning of a detailed description of the hero’s appearance.

Fragmentary portraits in the novel.

3. Conclusion. Functions of portraits in Goncharov’s novel.

I.A. Goncharov appears before us as a master of portraiture. His portraits are flexible, detailed, detailed. The portrait includes a description of the hero’s appearance, a description of his clothing, his surroundings, and incidental author’s remarks, and characterization, and landscapes, and the perception of other characters. In a word, in Goncharov we have a detailed portrait-essay. And in this the creative style of the writer is close to the creative style of N.V. Gogol.

Let's try to look at the portraits in Goncharov's novel "Oblomov". We find the first description of appearance already at the beginning of the work. This is a detailed portrait of Oblomov. In this description, Goncharov records the first impression and immediately gives a hint that not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance, that this portrait has its own subtext. There is some uncertainty and vagueness in the very description of the hero’s appearance. At the same time, critics noted that the muted tones here are in harmony with the colors of the landscape of the Central Russian strip (“Oblomov’s Dream”): “He was a man about thirty-two or three years old, of average height, pleasant appearance, with dark gray eyes, but with a lack of any definite idea, any concentration in facial features. The thought walked like a free bird across the face, fluttered in the eyes, sat on half-open lips, hid in the folds of the forehead, then completely disappeared, and then an even light of carelessness glowed throughout the whole body. From the face, carelessness passed into the poses of the whole body, even into the folds of the dressing gown.” And then we read: “Ilya Ilyich’s complexion was neither ruddy, nor dark, nor positively pale, but indifferent or seemed so, perhaps because Oblomov was somehow flabby beyond his years...” This portrait reveals to us the inner qualities of the hero, his habits: laziness, passive attitude towards life, his lack of any serious interests. Nothing occupies Oblomov, he has no habit of either mental or physical labor. The leitmotif of the entire description is softness. In the face of Ilya Ilyich - “the gentleness that was the dominant and main expression,” and this gentleness was an expression not only of the face, “but of the whole soul.” The same “softness” is in the hero’s movements, his oriental robe is “soft,” and his feet have “soft and wide” shoes.

In describing Oblomov’s body, Goncharov emphasizes the hero’s sedentary lifestyle, sybaritism, and lordly effeminacy: “In general, his body, judging by the matte, overly white color of his neck, small plump arms, soft shoulders, seemed too effeminate for a man.” Here the writer denotes the hero’s habits - “lying down”, love of loose clothing. Oblomov's home suit (oriental robe) becomes a symbol of his sedentary, measured life. It is characteristic that Oblomov throws away his robe at the time when he falls in love with Olga. Agafya Pshenitsyna takes it out and returns it to the owner.

Goncharov’s interior is, as it were, a continuation of the portrait: the room only at first glance seems “beautifully decorated.” But the “experienced eye” notes the ungraceful chairs, the unsteadiness of the shelves, the sagging back of the sofa. There are cobwebs scattered across the walls, the mirrors are covered with dust, the carpets are “stained”, there is always a plate left over from dinner on the table, a forgotten towel is lying on the sofa. The motif of sleep, deadness, and fossilization already appears in this interior. Describing the room, Goncharov notes: “one would think that no one lives here - everything was so dusty, faded and generally devoid of living traces of human presence.”

The motif of fossilization and immobility also appears directly in the description of the hero’s appearance. Goncharov notes that “neither fatigue nor boredom” could drive a certain expression from Oblomov’s face, the thought “hid in the folds of his forehead, then completely disappeared,” anxiety also could not take over his entire being - “all anxiety was resolved with a sigh and died away in apathy or in a drowsiness." And in this some researchers already find deep philosophical implications. As Weil and Genis note, “these frozen, petrified “folds” suggest an analogy with an ancient statue. The comparison is fundamentally important, which Goncharov consistently makes throughout the novel. In Oblomov’s figure, the golden ratio is observed, which gives a feeling of lightness, harmony and completeness to ancient sculpture. Oblomov’s stillness is graceful in its monumentality, it is endowed with a certain meaning.” The hero becomes funny, clumsy, awkward precisely in movement, in comparison with Stolz and Olga. In the house of Agafya Pshenitsyna, on the Vyborg side, in this “small Oblomovka”, he again turns into a statue: “He will sit, cross his legs, rest his head on his hand - he does all this so freely, calmly and beautifully... he is all so good , is so pure that he can do nothing, and does not.” What is the meaning of this monumentality of the hero? From the point of view of Stolz and Olga, who cannot imagine their life without movement, Oblomov lives without a goal. He is dead while alive. According to Oblomov himself, the border between life and death is conditional, it is rather a kind of intermediate state - a dream, a dream, Oblomovka. He ends up being the only genuine person in the novel. Researchers compare Olga and Stolz to machines, each of which has its own gear to engage with others. Oblomov is a complete, perfect statue. But this is precisely where the tragic paradox lies. Other heroes - “only fragments of Oblomov’s whole personality - are alive due to their imperfection, their incompleteness.” Oblomov is dead, he cannot exist in harmony with the world around him due to his perfection, harmony, and self-sufficiency. Thus, Goncharov’s portrait of the hero is included in the philosophical problematics of the novel.

The portrait of Stolz in the novel is given in contrast to the portrait of Oblomov. And this contrast is in the definiteness, clarity of lines and colors. “He is all made up of bones, muscles and nerves, like a blooded English horse. He is thin; he has almost no cheeks at all, that is, bone and muscle, but no sign of fatty roundness; complexion is even, darkish and no blush; the eyes, although a little greenish, are expressive.” The leitmotif of this portrait is movement. Stolz is pragmatic, businesslike: he serves, takes care of business, participates “in some company.” “He is constantly on the move: if society needs to send an agent to Belgium or England, they send him; you need to write some project or adapt a new idea to business - they choose it. Meanwhile, he goes out into the world and reads: when he has time, God knows.” In the image of Stolz, the writer emphasizes rationalism, the mental principle: “it seems that he controlled both sorrows and joys with the movement of his hands,” “he opened his umbrella while it was raining,” “suffered while the sorrow lasted,” “enjoyed joy as if plucked along the way.” flower." Most of all, Stolz was afraid of “imagination,” “every dream.” Thus, Stolz is presented in the novel not only as the external antipode of Oblomov, but also his antipode in his internal qualities.

The motif of the statue is heard in Goncharov and in the description of Olga Ilyinskaya. It is characteristic that she appears this way precisely in the imagination of Oblomov, who cannot forget her image after meeting her. “Olga in the strict sense was not a beauty, that is, there was no whiteness in her, no bright coloring of her cheeks and lips, and her eyes did not burn with rays of inner fire; there were no corals on the lips, no pearls in the mouth, no miniature hands, like those of a five-year-old child, with fingers shaped like grapes.

But if she were turned into a statue, she would be a statue of grace and harmony. The size of the head strictly corresponded to a somewhat tall stature; the size of the head corresponded to the oval and size of the face; all this, in turn, was in harmony with the shoulders, and the shoulders with the body...” However, this immobility here symbolizes not perfection and completeness (as in Oblomov’s portrait), but rather the “sleeping”, not yet awakened soul of the heroine.

Next we see a portrait of her, given in the author’s perception. And here what Oblomov does not notice is emphasized - the predominance of the rational principle. Goncharov here seems to give us an outsider’s view: “Whoever met her, even absent-minded, stopped for a moment in front of this so strictly and deliberately artistically created creature.

The nose formed a slightly noticeably convex, graceful line; the lips are thin and mostly compressed: a sign of a thought constantly directed at something. The same presence of a speaking thought shone in the vigilant, always cheerful, never-missing gaze of dark, gray-blue eyes. The eyebrows gave special beauty to the eyes: they were not arched, they did not round the eyes with two thin strings plucked with a finger - no, they were two light brown, fluffy, almost straight stripes, which rarely lay symmetrically: one was a line higher than the other, hence above the eyebrow there was a small fold in which something seemed to say, as if a thought rested there. Olga walked with her head tilted slightly forward, resting so slenderly and nobly on her thin, proud neck; she moved her whole body evenly, walking lightly, almost imperceptibly..."

The writer gives a dynamic portrait of the heroine, depicting her at certain moments in her life. This is how Olga appears in moments of singing: “Her cheeks and ears were red with excitement; sometimes a play of heart lightning would suddenly sparkle on her fresh face, a ray of such mature passion would flare up, as if she were experiencing a distant future time of life in her heart, and suddenly this instant ray would go out again, again her voice would sound fresh and silvery.” The author uses a comparison with natural phenomena, describing the “awakening of the heroine’s soul” when she understands Oblomov’s feelings: “... her face was gradually filled with consciousness; a ray of thought, guesswork made its way into every feature, and suddenly the whole face was illuminated with consciousness... The sun also sometimes, coming out from behind a cloud, little by little illuminates one bush, another, the roof, and suddenly bathes the whole landscape in light...” In Oblomov’s perception, Olga is given to us in that moment when her feeling is just emerging and Ilya is afraid to frighten him away. “A young, naive, almost childish smile never appeared on her lips, she never looked so wide, openly with her eyes when they expressed either a question, or bewilderment, or simple-minded curiosity, as if she had nothing to ask, there is nothing to know, nothing to be surprised at!

Her gaze did not follow him as before. She looked at him as if she had known him for a long time, studied him, finally, as if he was nothing to her, just like a baron...

There was no sternness, no yesterday's annoyance, she joked and even laughed, answered questions in detail, to which she would not have answered anything before. It was clear that she had decided to force herself to do what others were doing, which she had not done before. The freedom, the ease that allowed her to express everything that was on her mind, was no longer there. Where did everything suddenly go?” Here Ilya Ilyich analyzes Olga’s mood and feelings.

But Olga realizes her power over him, she takes on the role of a “guiding star.” And again the description of her appearance is given here in the perception of Ilya. Goncharov here does not give us a new portrait of the heroine, but uses the technique of psychological parallelism, reminding the reader of her already known features: “Her face was different, not the same one when they walked here, but the one with which he left her for the last time and which gave him such anxiety. And the caress was somehow restrained, the whole facial expression was so concentrated, so definite; he saw that it was impossible to play with guesses, hints and naive questions with her, that this childish, cheerful moment would be survived.”

The author also denotes Olga’s inner qualities, inserting subtle remarks, conveying Stolz’s impressions and the perception of her by secular society. In these descriptions, Goncharov emphasizes the simplicity and naturalness of the heroine. “Be that as it may, in a rare girl you will find such simplicity and natural freedom of look, word, and action. You’ll never read in her eyes: “Now I’ll purse my lip a little and think - I’m so pretty. I’ll look there and get scared, I’ll scream a little, and now they’ll run up to me. I’ll sit by the piano and stick out the tip of my leg a little...”

No affectation, no coquetry, no lies, no tinsel, no intent! For all of this, almost only Stolz appreciated her; for this, she sat through more than one mazurka alone...

Some considered her simple, short-sighted, because neither wise maxims about life, about love, nor quick, unexpected and bold remarks, nor read or overheard judgments about music and literature poured from her tongue: she spoke little, and only her own, unimportant - and smart and lively “gentlemen” walked around her; the quiet ones, on the contrary, considered her too sophisticated and were a little afraid.”

In the last part of the novel, as M.G. notes. Urtmintsev, in Olga’s portrait the motif of peace sounds twice. She finds happiness with the rational, reserved Stolz. “She fixed her eyes on the lake, on the distance, and thought so quietly, so deeply, as if she had fallen asleep. She wanted to catch what she was thinking, what she was feeling, but she couldn’t. Thoughts rushed as smoothly as waves, blood flowed so smoothly in my veins. She experienced happiness and could not determine where the boundaries were, what it was. She thought why she felt so quiet, peaceful, inviolably good, why she was at peace...” And at the end of the chapter we read: “She still sat as if she were sleeping - the sleep of her happiness was so quiet: she did not move, almost did not breathe.” The motif of peace here denotes a certain limitation of the heroine, the only possible life option for her.

In contrast to the poetic portrait of Olga, the novel gives a “prosaically everyday” portrait of Agafya Pshenitsyna. Here Goncharov only indicates the appearance features, describes the clothes, but says nothing about the habits, manners, and character traits of this heroine. “She was about thirty. She was very white and full in the face, so that the blush, it seemed, could not break through her cheeks. She had almost no eyebrows at all, but in their place there were two slightly swollen, shiny stripes with sparse blond hair. The eyes are grayish-simple, like the whole facial expression; the hands are white, but hard, with large knots of blue veins protruding outward.

The dress fit her tightly: it is clear that she did not resort to any art, not even an extra skirt, to increase the volume of her hips and reduce her waist. Because of this, even her closed bust, when she was without a headscarf, could serve a painter or sculptor as a model of a strong, healthy breast, without violating her modesty. Her dress, in relation to the elegant shawl and ceremonial cap, seemed old and shabby.” The hands of this heroine reveal her daily habit of work, and indeed in the future she appears as an excellent housewife. To Oblomov she seems modest and shy, we see that she is capable of much for the sake of love. However, Goncharov does not reflect all these qualities in the description of her appearance.

The novel also gives a detailed portrait of Tarantiev, Oblomov's fellow countryman. This is “a man of about forty, belonging to a large breed, tall, bulky in the shoulders and throughout the body, with large facial features, a large head, a strong, short neck, large protruding eyes, thick lips. A quick glance at this man gave rise to the idea of something rough and unkempt. It was clear that he was not chasing the elegance of the suit. It was not always possible to see him clean shaven. But he apparently didn’t care; he was not embarrassed by his suit and wore it with some kind of cynical dignity.” This portrait is also a sketch portrait. Goncharov gives us the life story of the hero, outlines his manners, habits, and character traits. “Tarantiev was a master only of talking; in words he decided everything clearly and easily, especially when it came to others; but as soon as it was necessary to move a finger, to get under way - in a word, to apply the theory he had created to the case and give it a practical move, to show discretion, speed - he was a completely different person: here he was missing ... "

Why is the description of Tarantiev in such detail in Goncharov’s novel? The fact is that this character not only plays an important role in the plot, but is also connected with the problems of the novel. Goncharov brings this hero closer to Oblomov. And this is not only about their common homeland - Oblomovka. Taranyev, just like the main character, develops in the novel the motif of unfulfilled hopes. By the will of fate, Tarantyev, who had received some education, was to remain a scribe for the rest of his life, “and meanwhile he carried within himself and was aware of a dormant force, locked inside him by hostile circumstances forever, without hope of manifestation, as they were locked, according to fairy tales, within the cramped, enchanted walls are the spirits of evil, deprived of the power to harm.” The same “dormant power” is present in Oblomov. Tarantiev is like a “reduced double” of Oblomov, a kind of parody of the main character.

Other descriptions of appearance in the novel are more brief and fragmentary. These are the portraits of Oblomov’s guests at the beginning of the novel - Volkov, Sudbinsky, Penkin, Alekseev. Researchers have noted here the similarity in the descriptions of these characters with the stylistic manner of N.V. Gogol in the poem “Dead Souls”.

Thus, the portrait in Goncharov’s novel performs a psychological function, revealing the character’s inner world, denoting the subtlety of mental movements, and outlining character. In addition, the portraits of the writer are related to the philosophical issues of the novel.

Portraits and interiors in Goncharov's novel "Oblomov"

The novel, written in 1859, from the first days of publication to this day, like any great and powerful work of world classics, evokes various emotions. Disputes and disagreements - there are no indifferent people and never have been. Hence the many critical articles: Dobrolyubov, Annensky, Druzhinin and others - each of them gave his own, in some ways similar, and in some ways completely divergent, definition of Oblomov and Oblomovism.

In my opinion, Oblomovism is a state of not only the external characteristics of the hero, but also the entire life organization, their totality.

The artist’s desire to create works of art is based on an interest in man. But each person is a personality, character, individuality, and a special, unique appearance, and the environment in which he exists, and his home, and the world of things surrounding him, and much more... Walking through life, a person interacts with himself, with people close and distant to him, with time, with nature... And therefore, when creating an image of a person in art, the artist seems to look at him from different sides, recreating and describing him in different ways. The artist is interested in everything about a person - his face and clothes, habits and thoughts, his home and place of work, his friends and enemies, his relationships with the human world and the natural world. In literature, such interest takes a special artistic form, and the deeper you can study the features of this form, the more fully the content of the image of a person in the art of words will be revealed to you, the closer the artist and his view of man will become to you.

That is, for the concept of the work and the main intention of the author, it is necessary to compare both the portrait data of the heroes and the situation (its change) in which this or that hero is directly located. To do this, we will first consider the definitions of the terms “portrait” and “interior” and then proceed to their direct application and comparison in the novel by A.I. Goncharov "Oblomov".

Having picked up the book and started reading Roma, already on the first page we pay attention to the detailed description of the appearance, i.e. portrait of a hero. The portrait description of the hero is immediately followed by a description of the interior. Here the author uses the complementarity of the portrait with the interior

Let us carefully read the portrait of the hero “He was a man of thirty-two or three years old, of average height, pleasant appearance, with dark gray eyes, but with the absence of any definite idea, any concentration in his facial features. The thought walked like a free bird across the face, fluttered in the eyes, sat on half-open lips, hid in the folds of the forehead, then completely disappeared, and then an even light of carelessness glowed throughout the face. From the face, carelessness passed into the poses of the whole body, even into the folds of the dressing gown. Sometimes his gaze darkened with an expression as if of fatigue or boredom; but neither fatigue nor boredom could for a moment drive away from the face the softness that was the dominant and fundamental expression, not only of the face, but of the whole soul; and the soul shone so openly and clearly in the eyes, in the smile, in every movement of the head and hand... Ilya Ilyich’s complexion was neither ruddy, nor dark, nor positively pale, but indifferent or seemed so, perhaps because that Oblomov was somehow flabby beyond his years: from lack of movement, or air, or maybe both.” The finest details: eyes, complexion, pose. After reading this passage, not only the author’s, but also the reader’s attitude towards the hero is immediately formed. This image deserves respect and indignation. The image is lazy, weak-willed, incredibly careless and serene, but at the same time he is pure and open-hearted, he is completely incapable of meanness. Oblomov, realizing the “truth” that exists in this world, voluntarily moves away from a big, active life, limiting himself to the confines of his own apartment.

The description of the apartment, its negligence, is similar to the hero’s state of mind: “The room where Ilya Ilyich was lying seemed wonderful at first glance

cleaned up. There was a mahogany bureau, two sofas upholstered in silk

material, beautiful screens with embroidered birds and fruits unprecedented in nature. There were silk curtains, carpets, several paintings, bronze, porcelain and many beautiful little things... if you examine everything there more closely, you were struck by the neglect and negligence that dominated it. On the walls, near the paintings, cobwebs, saturated with dust, were molded in the form of festoons; mirrors, instead of reflecting objects, could rather serve as tablets for writing down some notes on them in the dust for memory. The carpets were stained. There was a forgotten towel on the sofa; On rare mornings there was not a plate with a salt shaker and a gnawed bone on the table that had not been cleared away from yesterday’s dinner, and there were no bread crumbs lying around.”

The entire interior, like Ilya Ilyich himself, is soft, sleepy, decorated only for show and then with features of laziness and indifference.

But I would like to dwell in more detail on such an interior item as a sofa. Yes, every person has a place and circumstances in which he feels “like a king.” He is protected, free, contented, self-sufficient. Goncharov's Oblomov has such a royal throne - a sofa. This is not just a piece of furniture, not a place of rest and after righteous labors. This is a sacred place where all wishes come true. A fantastic world is being built in which Oblomov does not rule - for this, efforts must be made - he takes for granted peace, contentment, satiety. And Oblomov has devoted slaves at his service, if you call a spade a spade.

Oblomov became close, merged with his sofa. But it’s not only laziness that prevents Oblomov from leaving it. There, around, is real life, which is not arranged at all for the service and pleasure of the master. There you need to prove something, achieve something. There they check what kind of person you are and whether you have the right to what you want. And on the sofa it’s calm, cozy - and there’s order in the kingdom... and Zakhar is in place...

This whole sleepy kingdom, where the owner himself becomes the object of the furnishings, lives his unhurried, suspended life, but only until his old friend, the Russian German, Stolz, comes to visit Oblomov.

Stolz, the same age as Oblomov, was brought up from early childhood in the strictness of his father and the love of his mother. “He is all made up of bones, muscles and nerves, like a blooded English horse. He is thin; he has almost no cheeks at all, that is, there is bone and muscle, but no sign of fatty roundness; complexion is even, darkish and no blush; The eyes, although a little greenish, are expressive. He had no unnecessary movements. If he was sitting, he sat quietly, but if he acted, he used as many facial expressions as necessary. Just as he had nothing superfluous in his body, so in the moral practices of his life he sought a balance between the practical aspects and the subtle needs of the spirit. The two sides walked parallel, crossing and intertwining along the way, but never getting tangled in heavy, insoluble knots. He walked firmly, cheerfully; lived according to a budget, trying to spend every day, like every ruble, with every minute, never dozing control of the time spent, labor, strength of soul and heart. It seems that he controlled both sorrows and joys, like the movement of his hands, the steps of his feet, or how he dealt with bad and good weather.” Stolz is an integral and active person, his arrival marked a new stage in Oblomov’s life. Agile and energetic, he does not allow Ilya Ilyich to idle. Behavior. Andrei’s appearance and whole image is a clear contrast with that place, that apartment where Oblomov is busy lying peacefully. Stolz’s element is not a sleepy kingdom, but an eternal movement forward, overcoming life’s obstacles. Apparently this is why there is no specific description of Stolz’s house in the novel. Goncharov only writes that he “served, retired... Minded his own affairs,... found a house and money,... learned Europe as his estate,... saw Russia up and down,... travels into the world.” Always striving somewhere, he, like any other busy person, does not have time for home comfort, slippers and measured lying in idleness.

One of the main means of combating laziness is to change your place of permanent residence. Andrei knew how to bring the hero into the public eye. It is thanks to Stolz that Oblomov meets Olga Ilyinichna. “Olga in the strict sense was not a beauty, that is, there was no whiteness in her, no bright coloring of her cheeks and lips, and her eyes did not burn with rays of inner fire; there were no corals on the lips, no pearls in the mouth, no miniature hands, like those of a five-year-old child, with fingers in the shape of grapes. But if she were turned into a statue, she would be a statue of grace and harmony. The size of the head strictly corresponded to a somewhat tall stature; the size of the head corresponded to the oval and size of the face; all this, in turn, was in harmony with the shoulders, the shoulders with the figure... The nose formed a slightly noticeably convex, graceful line; the lips are thin and mostly compressed: a sign of a thought constantly directed at something. The same presence of a speaking thought shone in the vigilant, always cheerful, never-missing gaze of dark, gray-blue eyes. The eyebrows gave special beauty to the eyes: they were not arched, they did not round the eyes with two thin strings plucked with a finger - no, they were two light brown, fluffy, almost straight stripes, which rarely lay symmetrically: one was a line higher than the other, hence above the eyebrow there was a small fold in which something seemed to say, as if a thought rested there” - just like that, in just a few details I.A. Goncharov gives a portrait of his heroine. Here Goncharov notes in several details everything that is so valued in a woman: the absence of artificiality, beauty that is not frozen, but living. Also, for only a few moments we see Ilyinskaya’s house, and like the housewife, it is strict and without frills: “piano”, “statue in the corner”, “deep Viennese armchair next to the bookcase”.

After the first meeting with Olga, Ilya Ilyich begins to change and change the situation in the apartment. Of course, these are not global changes, but the path has been outlined and a push has been given. Only for a while, but Oblomov changes beyond recognition: under the influence of a strong feeling, incredible transformations took place in him - a greasy robe is abandoned, Oblomov gets out of bed as soon as he wakes up, reads books, newspapers, is energetic, active, and having moved to the dacha closer to Olga, visits her several times a day. The description of the place, or rather the interior in which Oblomov is located, is reduced, like Stolz’s, to a minimum. Now we only know that he is at the dacha, that “near the dacha there was a lake, a huge park,” but this is no longer a description of the interior, which limits the hero to its boundaries, but of free nature.

However, Ilya Ilyich understands that love, which carries within itself the need for action and self-improvement, is doomed in his case. The visions of my former life, the sofa, the carefree sleep are still too fresh in my memory. He needs a different feeling, a different life that would connect the world of today and the impressions of a cozy environment.

Olga at one time talks about how and from what side she influences Oblomov. She is “so timid and silent” and builds in the hero that ideal world, that ideal interior in which she would be comfortable living, while she does not agree to make concessions.

Oblomov and Olga expect the impossible from each other. She is activity, will energy; her ideal is Stolz with the spiritual qualities of Ilya Ilyich. But the more she tries to change Ilya, the more she understands his inner world, and the further he isolates himself from her. He wants reckless love, which would bring warmth and comfort to his home and soul. But Olga loves only the brainchild she created.

A huge resonance occurs in Oblomov’s soul. They tore him out of his world, his image, his robe, tried to remake him, but it didn’t work. And then the hero’s heart breaks, a discord with the new world occurs. Leaving for the city, he needs to rent an apartment and he ends up with Agafya Matveevna Pshenichnaya.

The image of Pshenichnaya never aroused much interest among critics of the novel: her nature is rather rude and primitive. She was usually viewed as “a terrible woman, symbolizing the depth of Ilya Ilyich’s fall. Let's look at her portrait: “She was about thirty years old. She was very white and full in the face, so that the blush, it seemed, could not break through her cheeks. She had almost no eyebrows at all, but in their place there were two slightly swollen, shiny stripes with sparse blond hair. The eyes are grayish-simple, like the whole facial expression; the hands are white, but hard, with large knots of blue veins protruding outward. The dress fit her tightly: it is clear that she did not resort to any art, not even an extra skirt, to increase the volume of her hips and reduce her waist. Because of this, even her closed bust, when she was without a headscarf, could serve a painter or sculptor as a model of a strong, healthy breast, without violating her modesty. Her dress, in relation to the elegant shawl and ceremonial cap, seemed old and shabby.” Here Goncharov paints us an image of a hardworking, honest, homely woman, but very limited. She had no goal in life, there was only a goal for each day - to feed her, put her clothes in order (“meaning: the peace and comfort of Ilya Ilyich...”)

Pshenitsyna is at constant work (“there is always work”), then we see her cooking something, then she cleans the master’s house. Her constantly flashing elbows attract Oblomov’s attention not only with her beauty, but also with Agafya’s activity.

“Suddenly his eyes stopped on familiar objects: the whole room

was filled with his goods. The tables are covered in dust; chairs piled up on

bed; mattresses, dishes in disarray, cabinets” - this is how Oblomov first saw Pshenitsyna’s house. His first reaction was the words: “What disgusting” - however, Ilya Ilyich understands perfectly well that the interior is similar to his home, to that sleepy kingdom where everything is comfortable and calm.

Pshenitsyna’s image is not limited in this setting, but seeing that Ilya Ilyich is comfortable and pleasant in such an environment, she begins to arrange the house to his taste.

At this time, Oblomov realizes that he has nowhere else to strive in life, that it is here, in the house on the Vyborg side, that is the ideal place for his existence. It is Agafya Pshenitsyna who brings Oblomov’s old dressing gown back to life.

And again Ilya Ilyich Oblomov returns to the place where the story began: he returns to the sofa (“He just wanted to sit on the sofa...”). Pshenitsyna unselfishly loved Oblomov, however, with her love and care she again drowned out the human qualities that had awakened in him. Thus, it was she who completed the process of Oblomov’s spiritual death, but she did not do it out of malice. She found joy and happiness in deep devotion to him, and thus did everything to make Ilya Ilyich’s existence closer to his life at home.

A good, comfortable life, everything flows as usual and it seems that you can live like this forever, but... death does not choose time.

What about Stolz and Olga?

Olga married Stolz, they settled in Crimea, in a modest house. But this house, its decoration “They settled in a quiet corner, on the seashore. Their house was modest and small. Its internal structure also had its own style, as did the external architecture, and all the decoration bore the stamp of thought and personal taste of the owners.” The furniture in their house was not comfortable, but there were many engravings, statues, books, yellowed with time, which speaks of the education, high culture of the owners, for whom old books, coins, engravings are valuable, who constantly find something new in them for myself. But did they become happy together? Undoubtedly, their images and aspirations were largely realized in this environment; everything they wanted to see in themselves and their family came true. Common sense still overcomes the feelings that tormented her, she loves her husband and believes in him. But everything is too ordinary and mechanical, hence such melancholy in the atmosphere of their home. With Oblomov, part of Olga’s soul dies, striving for the better, which she tried to teach Ilya Ilyich.

So, in conclusion of the work I have done, we can conclude that throughout the entire novel, along with the hero, the interiors against which the main character is presented also change. The interiors and images of more minor characters are also connected with each other.

We can say that we have traced the evolution of Oblomov’s development and the change (change) of the background of the action.

Portraits change with interiors, interiors with portraits... The close relationship of these details of the novel helps us better reveal the image of the main character, understand the state of his soul, body, stage of development.