The concept and specificity of cultural globalization. Cultural globalization as a process of formation of a new global culture

Introduction. One of the fundamental phenomena that today determines the appearance and structure of life of the human community in literally all its aspects - social, economic, cultural and political - is globalization.

Today, the fact of a very significant interaction between globalization and national and ethnic cultures is quite obvious. In the course of this, not only are the traditional areas of distribution of the world's main religions and faiths being reshaped, often finding themselves in new conditions of existence and interaction, but they are also being coupled with relatively new values, such as, for example, the principles of civil society. All this requires careful study and in-depth analysis - both from experts and from many stakeholders who are not indifferent to the fate of culture, especially in today's rapidly changing world.

Main part. The process of globalization of culture creates a close connection between economic and cultural disciplines. The latter is so significant that we can talk about the economization of culture and the culturalization of the economy. This impact is determined by the fact that social production is increasingly oriented towards the creation of intellectual, cultural and spiritual goods and services or the production of “symbols”, and in the sphere of culture the laws of the market and competition (“mass culture”) are increasingly felt.

Today, culture must be conceptualized as a crucial aspect of globalization, rather than a mere reaction to economic globalization. However, one should not assume that the globalization of culture is the establishment of cultural homogeneity on a worldwide scale. This process involves cultural clashes and contradictions. Conflicts and clashes between different cultures and civilizations are the main factor in the modern multipolar world. In the context of globalization, a new philosophy is needed - a philosophy of mutual understanding, considered in the context of dialogue between East and West, South and North.

“Compression” of the social world, on the one hand, and fast growth The world's awareness of its own “expansion,” on the other hand, creates a global condition in which civilizations, regions, nation-states, and stateless indigenous peoples construct their histories and identities. The sense of uniqueness and identity among peoples and regions has sharply increased throughout the world. We can say that the protection of local national traditions and characteristics is a global phenomenon.

Therefore, the ability for self-preservation is fundamentally specific crops is possible, but this possibility is realized only under certain conditions.

In the modern world there is a transition from national culture to global culture, the language of which is English. The American dollar is used all over the world, Western mass culture is rapidly penetrating into our lives, the model of a liberal democratic society is being implemented to one degree or another in many countries, a global information space is being created (the Internet and other, the latest information and communication technologies), globalization is taking place Western culture, arises new reality– virtual world and virtual person. Thus, space and time become closer and closer, even merging. “Anti-globalists” and “anti-Westerners” emerged. Under these conditions it becomes extremely topical issue about the preservation of linguistic and cultural identity, originality and uniqueness of the culture of other peoples of the planet.

To solve the most difficult task of the entry of national culture into the space of world culture, the determining factor is not the desire to please, but the ability to remain oneself. In no case should you isolate yourself within the confines of your culture; you must go out into the world cultural space, but you must go out with what you have, since it is this content that has value. Moreover, one cannot force national culture to “sell itself” and be prepared for the fact that it will not be accepted, considered, understood, or appreciated. Consequently, it is “not suitable” for the era, time.

However, within the limits of what is permitted, national culture can do something for a better perception of itself. It can take advantage of the opportunities that globalization provides. She can replicate her image and “come to every home.” It is possible that, without being accepted with delight on the “best stages of the world,” national culture will find a response in other regions, and from there it will be more widely accepted.

But there will be no big disaster, as noted by the famous Kazakh philosopher A.G. Kosichenko, if the national culture is not widely understood. In the end, it is, first of all, a national culture, and, therefore, the culture of a particular nation. National culture can and should educate a person on the values inherent in this culture. And if this real culture, then such a person is interesting to the world, because through the cultural identity of a person a universal human culture emerges. National culture is valuable precisely for its specific values, since these values are nothing more than another way of seeing the world and the meaning of being in this world. This soil cannot be abandoned, otherwise the national culture will disappear.

Conclusion. Thus, the process of globalization not only gives rise to monotonous structures in economics and politics various countries world, but also leads to “glocalization” - adaptation of elements of modern Western culture to local conditions and local traditions. The heterogeneity of regional forms of human activity is becoming the norm. On this basis, it is possible not only to preserve, but also to revive and master the culture and spirituality of the people, and develop local cultural traditions and local civilizations. Globalization requires from local cultures and values not unconditional submission, but selective selective perception and assimilation of new experiences of other civilizations, which is possible only in the process of constructive dialogue with them. This is especially necessary for the young independent states of the post-Soviet space, strengthening their national security. Therefore, we urgently need the development of global studies as a form of interdisciplinary research that allows us to correctly assess the situation and find ways to solve them.

List of used literature:

1. Kravchenko A.I. Culturology: Textbook for universities. - 3rd ed. M: Academic Project, 2002. - 496 p. Series (Gaudeamus).

ISBN 5-8291-0167-Х

2. Fedotova N.N. Is it possible World culture? // Philosophical Sciences. No. 4. 2000. pp. 58-68.

3. Biryukova M.A. Globalization: integration and differentiation of cultures, // Philosophical Sciences. No. 4. 2000. P.33-42.

4. Kosichenko A.G. National cultures in the process of globalization // WWW.orda.kz. Electronic information and analytical bulletin. Nos. 8, 9.

Gglobalization and cultural issues

Introduction

At a certain level of development, problems begin to cross borders and spread throughout the planet, regardless of the specific socio-political conditions existing in different countries - they form a global problem. Aurelio Peccei. "Human qualities"

Globalization!.. There is hardly any other phenomenon today that would cause such heated discussions and fierce debate. And this is natural. Firstly, it, in one way or another, albeit to varying degrees, influences the lives of the overwhelming number of people living on our planet. Secondly, it is so complex and contradictory that it defies any simple explanation.

Globalization affects almost all aspects and aspects of the life of a modern person. The main thing in it is the increasingly expanding exchange of information of a scientific, economic, political, personal, everyday, socio-cultural and other nature across all state and national cultural barriers. To consider all these aspects, a monograph is not enough. Therefore, we will try to present the essence of the problem, focusing on globalization cultural space.

Several years ago, a British researcher of traditional ethnic cultures, finding herself in a remote African village, was invited on the first evening to visit one of its inhabitants. She went to him in anticipation of the long-awaited acquaintance with the traditional forms of leisure for the inhabitants of the African hinterland. Alas, there was bitter disappointment. She witnessed a collective video viewing of a new Hollywood film, which by that time had not yet even been released on the screens of London cinemas. Thus she came face to face with one of the typical manifestations of the globalization of culture.

Here’s another interesting example: a few years ago, the Tuareg, the largest tribe of nomads in the Sahara, began their traditional annual migration ten days later only because it was important for them to finish watching the American television series “Dallas.” And such examples can be multiplied: after all, in the Lower Bavarian village they watch a television series about life in Dallas, wear jeans and smoke Marlboro cigarettes in the same way, as in Calcutta, Singapore or in the “bidonvilles” near Rio de Janeiro. Residents of many countries today watch Western-made films and advertisements on television and video, consume “instant food,” buy goods manufactured abroad, and also receive their livelihood by serving the flow of foreign tourists. The global economy absorbs and integrates the local one, and traditional culture is experiencing increasingly powerful foreign cultural influences.

Now we easily and habitually move from one country to another. It is enough to spend three hours on a plane, and you are already in another part of the world. Mobile phones, satellite television, computers, and the Internet provide information about events and culture of various countries and continents. All this means that in recent decades humanity has entered into a fundamentally new stage of its development. We are talking about the formation of a planetary civilization on the basis, on the one hand, of the organic unity of the world community, and on the other, of the pluralistic coexistence of cultures and religions of the peoples of the world.

Historical roots of globalization

A careful look at history shows that globalization is not a phenomenon of the late twentieth century. Its sprouts can be found in the mythological layers of cultures of different peoples. Since time immemorial, people have believed that once all the children of the Earth lived as a single monolingual family, and then they were “as yet wounded by diversity.” They believed that the day would come when sin would be atoned for, and people belonging to different linguistic nations and races, professing different political convictions and religious beliefs, would establish strong ties with each other, feel themselves to be part of a universal human whole, and join forces in the name of a common cause. The ancient Greeks, oriental sages, and European medieval thinkers spoke about this.

It is enough to recall cosmopolitanism - the ideology of “world citizenship”, which has always been characterized by the idea of the world as the fatherland of all people. The emergence of this ideology was historically associated with the decline of the Greek city-states after the Peloponnesian Wars. Then a person who had previously considered himself a citizen of his city-state began to feel a sense of belonging to a larger community, “world citizenship.” First clearly formulated within the Cynic philosophical school, this consciousness was further developed by the Stoics, especially in the Roman era. This was greatly facilitated by the multinational character of the Roman Empire. But only the fifteenth century became the century in which humanity in the full sense of the word opened the globe for yourself. The caravels of H. Columbus, F. Magellan and other navigators carried European values, traditions, religion, customs, tools, tools, etc. with them to Africa, Asia and America. In the figurative expression of G. Hegel, “the world has become round for Europeans.” Later, during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, the idea of world citizenship was developed by A. Dante, T. Campanella, G. Lessing, I. Goethe, I. Schiller, I. Kant, I. Fichte and others. The dream of an integrated humanity captivated many philosophers of the 19th century and 20th centuries in the East and West. This was facilitated by the active colonization of Africa, Hindustan and vast territories of Asia.

It has long been known that the innovations of one civilization are soon adopted by other peoples. But in earlier times these were, as a rule, just purely technological borrowings. Because the Chinese invented gunpowder, the compass and paper, the Europeans who borrowed these technologies did not become “sinicized.” And because half of China rides a bicycle invented by Europeans, traditional Chinese culture has not become Europeanized at all. But there were other examples. Thus, Peter I, who transplanted not only European technologies, but also significant fragments of European culture onto Russian soil, significantly changed Russia.

Of course, everything said above constituted only the prehistory of modern cultural globalization. In reality, the date of its origin can apparently be considered 1870, when the British agency Reuters, together with the French company HAVAS, divided the globe into zones for the exclusive collection of information.

At the beginning of the 20th century. ideas about the formation of the United States of Europe spread. Later they took on a form associated with the creation of new centralized world structures. On this wave, the so-called mondialism (from the French monde - world) arose - a cosmopolitan movement for the creation of a world government.

The 20th century gradually developed a global ethics. Slowly, with difficulty, moral norms made their way into international law. The Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals punished war criminals on behalf of all mankind, creating the most important precedent for the international protection of human rights. Globalization processes have become noticeable in the religious area. Here it is necessary to mention “ecumenism” (from the Greek oikumene - inhabited world, universe) - a movement for the unification of all Christian denominations that arose at the beginning of the 20th century.

Now we will look at M.O. Rudenko’s article on cultural globalization, from which we will try to understand what the danger of this process is and draw certain conclusions.

Cultural globalization

“If culture is considered primarily as lifestyle or the order within which people construct meaning through practices of symbolic representation, then cultural globalization should be understood primarily as changes in the context of meaning construction, changes in identity, a sense of place and self in relation to a given place, general ideas, values, aspirations, myths, hopes and fears.

The constitutive role of culture in the process of globalization is determined by the potentially global consequences of culturally rich “local” actions. In other words, we are talking about reflexivity(the ability that an explanation (theory) has when it turns to itself, for example, the sociology of knowledge, the sociology of sociology; the peculiarity of reflexive social explanations and theories of all types is that they can also act in the direction of reproducing or transforming those social situations addressed) the nature of social activity: local customs and lifestyles at the present stage have global consequences, while there is also an intervention of the local in global processes.

However, more importantly, control consumerism(organized movement of citizens and/or government organizations for expanding rights and increasing the influence of buyers on sellers and producers of goods) over ideas in the context of globalization is truly total. Global capitalism seeks to subjugate, commercialize and commodify all ideas and material products in which ideas are contained - television, advertising, newspapers, books, films, etc.

Accordingly, an important factor-catalyst for the processes of borrowing and subsequent institutionalization of cultural practices is their commercial potential - everything that can make a profit is doomed to commercialization in a market economy. Today we can state that in the world, including in Russia, there is a demand and fashion for new, globalized cultural practices.

Globalization in the sphere of culture leads to the intensification of the processes underlying the formation of a wide range of phenomena of modern culture - the “culture of excess” (J. Baudrillard’s term), which is characterized by an oversaturation of meanings and a lack of value judgments, recataloging, transcoding, rewriting all familiar things in new terms .

Although the result of globalization processes cannot be cultural homogenization (the creation of a single structure) or a decrease in cultural diversity in the world, globalization is quite capable of leading to an increase in the uniformity of different cultures, not least through the mechanisms of consumerism. Cultural globalization can occur on the basis of Western values - the Reformation, Enlightenment and Renaissance - values that essentially gave rise to today's crisis phenomena in the world, or it can lead to the development of a new system of values as a result of a new spiritual revolution, and then it will be carried out on the basis of this new value systems.

It seems that such prerequisites are undoubtedly being formed, and indirect confirmation of this is the growing diversity of new cultural practices, actively reflected by public consciousness, including methods of sociocultural analysis, which involve consideration of the semantic world of meanings in a socio-historical context.”

Analysis of cultural unification

Thus, after reading the article we understand that the unification of cultures is increasingly becoming global problem, fraught with serious threats. The world in which we have to live is becoming less bright and less and less colored by local color. Many customs, ceremonies, rituals, and forms of behavior that in the past gave humanity its folklore and ethnographic diversity are gradually disappearing as the bulk of society adopts new standard forms of life.

Can traditional cultures of peoples exist in the conditions of such globalization? Will peoples be able to preserve their cultural identity, will many of their features not disappear irreversibly, being eroded in the conditions of increasing standardization of the way of life? national cultures? Indeed, unlike the adaptation of products - Coca-Cola, chewing gum and jeans - foreign cultural influence, for example, in the field of music and literature, cinema and television, is by no means a harmless phenomenon, since it can affect vital fragments of the worldview. Artistic images penetrate across borders and customs into the core of national culture, gradually subjecting it to unpredictable changes.

Historically established cultures represent the main source from which personality draws life meanings, building a hierarchy of its values. A person who has lost his cultural roots is threatened with psychological disorientation, the loss of internal rules that regulate and streamline his aspirations and goals.

But the globalization of culture, leading to its unification, carries risks not only for the individual, but also for society as a whole. The fact is that ethnocultural diversity in the modern world performs many vital functions. So, social history indicates that different ethnic groups are guided by different approaches to solving the problems that arise before them. Thus, in one culture a passion for money may dominate, in another - technical knowledge, in a third - political ideals, in a fourth - belief in immortality. No one can predict the course of history, no one knows what abilities and qualities humanity will need to survive in the future - near and distant. Consequently, it must have a rich arsenal of properties, each of which may be required to adequately respond to the challenges of history - social and natural. That is why care must be taken that cultural interaction does not lead to homogenization, i.e. to the destruction of a specific ethnic picture of the world.

It is obvious that the process of cultural globalization itself initially contains a certain potential for conflict. “Cultural imperialism” inevitably causes a response - an increased need for self-affirmation, preservation of the basic elements of one’s national picture of the world and way of life. This desire often takes the aggressive form of categorical rejection of global cultural changes. The general process of destruction of borders is contrasted with cultural isolation and hypertrophied pride in one’s originality. This leads to numerous ethno-religious conflicts, the emergence of nationalist tendencies in politics, and the growth of regional fundamentalist movements. For example, processes of religious radicalization have begun in the culture of many countries of the Islamic world. This also applies to the traditional cultures of the Caucasus, Africa, some countries of Latin America and Asia. Recently, there has been a rise in religious fundamentalism also within the Christian tradition. The level of violence on ethnic and national grounds is increasing: Palestinians and Kurds, Sikhs and Tamils, Irish Catholics and Welsh, Armenians and Azerbaijanis do not want to agree with the globalization of culture, which threatens them with assimilation. Therefore, terrorism and national liberation wars remain on the agenda. All this can be interpreted as a form of a specific reaction to globalization.

Naturally, the problem of globalization of culture becomes most relevant for developing countries. But at the same time, it also faces developed countries, for example, France, Canada, and small European states experiencing the expansion of mass - and, above all, American - culture. Over the past decades, governments and international institutions, such as those of a united Europe, have been trying to combat “cultural imperialism.” In the majority European countries There are now laws protecting cultural identity, and there are special subsidy systems aimed at supporting national culture. There are even attempts to control the moral and cultural aspects of the content of artistic production.

“Why did everyone make such a terrible mistake? - exclaims Professor J. Comaroff. - Why, while, according to all calculations, it should have died quietly, the politics of cultural self-awareness suddenly revived with a noise on a worldwide scale? And is this a revival? Could it be that this is a completely new social phenomenon?

A paradoxical situation is emerging - the closer and more intense the ties between countries and peoples become, the higher value and global processes and problems acquire scale, the more diverse the civilizational and culturally and the world becomes more “mosaic”. To describe this paradox, scientists have come up with a special term - “glocalization.” That is, at the same time, globalization and “localization” are the protection of the uniqueness of traditional cultures.

Dissatisfaction with globalization resulted in a massive interethnic protest movement, called “anti-globalist.” It was compiled by students, church communities, environmentalists, trade unionists, non-governmental organizations, leftists, pacifists, and anarchists. At first, after a loud and noisy wave of protests in Seattle, Prague and Genoa, they were perceived mainly as troublemakers, rowdies who did not know what to offer in return for the globalization policy pursued by the “seven” developed countries. But after the First and then the Second Social Forum (2001 and 2002), it became clear that anti-globalism had already outgrown the framework of a purely “protest” movement and clearly did not amount to a denial of the very idea of global integration.

“Anti-globalists” are often accused of not knowing what they want. To this they respond: “We want a truly global world where citizens of all states are citizens and not just consumers. A world where citizens' desire to protect their way of life and environment is not undermined by trade and investment agreements." We are talking about such generally significant guidelines as social justice, global democracy based on human rights, and sustainable development. The "anti-globalization" movement has become a factor today big politics, which governments, international organizations and corporations are forced to reckon with. On the side of the “anti-globalists” is the sympathy of a significant part of the Western public, who are seriously concerned about the negative aspects of globalization.

Globalization is not an automatic process that will end in a conflict-free and ideal world. It is fraught with both new opportunities and new risks, the consequences of which for us can be very significant. But people are not passive observers, they are not so much spectators as creators own history. Therefore, they have the opportunity to correct the current globalization - all peoples and all cultures should benefit from these processes. Therefore, globalization may lead not to the unification of cultures according to the American model of a “consumer society,” but to “multiculturalism.” In other words, as a result of the emergence of a global system, each national culture will occupy an equal position among other cultures. Or, to put it even more simply, global civilization should not lead to a single average global culture.

Tutoring

Need help studying a topic?

Our specialists will advise or provide tutoring services on topics that interest you.

Submit your application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.

15. GLOBALIZATION OF CULTURE

15.1. The concept of "globalization"

In the socio-humanitarian discussion of recent decades, the central place is occupied by the understanding of such categories of modern globalized reality as global, local, transnational. The scientific analysis of the problems of modern societies, thus, takes into account and brings to the fore the global social and political context - various networks of social, political, economic communications covering the whole world, turning it into a “single social space”. Previously separated societies, cultures, and people are now in constant and almost inevitable contact. The ever-increasing development of the global context of communication results in new, previously unprecedented socio-political and religious conflicts, which arise, in particular, due to the clash at the local level of the national state of culturally different models. At the same time, the new global context weakens and even erases the rigid boundaries of sociocultural differences. Modern sociologists and cultural scientists engaged in understanding the content and trends of the globalization process are paying more and more attention to the problem of how cultural and personal identity changes, how national, non-governmental organizations, social movements, tourism, migration, interethnic and intercultural contacts between societies lead to the establishment of new translocal, transsocietal identities.

Global social reality blurs the boundaries of national cultures, and therefore the ethnic, national and religious traditions that comprise them. In this regard, globalization theorists raise the question of the tendency and intention of the globalization process in relation to specific cultures: will the progressive homogenization of cultures lead to their fusion in the cauldron of “global culture”, or will specific cultures not disappear, but only the context of their existence will change. The answer to this question involves finding out what “global culture” is, what its components and development trends are.

Theorists of globalization, concentrating their attention on the social, cultural and ideological dimensions of this process, identify “imaginary communities” or “imaginary worlds” generated by global communication as one of the central units of analysis of such dimensions. New “imagined communities” are multidimensional worlds created by social groups in global space.

In domestic and foreign science, a number of approaches to the analysis and interpretation of modern processes, referred to as globalization processes, have developed. Definition conceptual apparatus concepts aimed at analyzing globalization processes directly depends on the scientific discipline in which these theoretical and methodological approaches are formulated. Today, independent scientific theories and concepts of globalization have been created within the framework of such disciplines as political economy, political science, sociology and cultural studies. In perspective cultural analysis of modern globalization processes, the most productive are those concepts and theories of globalization that were initially formulated at the intersection of sociology and cultural studies, and the subject of conceptualization in them was the phenomenon of global culture.

This section will examine the concepts of global culture and cultural globalization proposed in the works of R. Robertson, P. Berger, E. D. Smith, A. Appadurai. They represent two opposing strands of international scientific debate about the cultural fate of globalization. Within the first direction, initiated by Robertson, the phenomenon of global culture is defined as an organic consequence of the universal history of mankind, which entered the 15th century. in the era of globalization. Globalization is conceptualized here as a process of compression of the world, its transformation into a single sociocultural integrity. This process has two main vectors of development – global institutionalization of the lifeworld and localization of globality.

The second direction, represented by the concepts of Smith and Appadurai, interprets the phenomenon of global culture as an ahistorical, artificially created ideological construct, actively promoted and implemented through the efforts of mass media and modern technologies. Global culture is a two-faced Janus, the product of the American and European vision of the universal future of the world economy, politics, religion, communication and sociality.

15.2. Sociocultural dynamics of globalization

So, in the context of the paradigm set by Robertson, globalization is conceptualized as a series of empirically recorded changes, heterogeneous, but united by the logic of transforming the world into a single sociocultural space. A vital role in the systematization of the global world is assigned to global human consciousness. It should be noted that Robertson calls for abandoning the use of the concept of “culture,” considering it empty in content and reflecting only the unsuccessful attempts of anthropologists to talk about primitive, unliterate communities, without involving sociological concepts and concepts. Robertson believes it is necessary to raise the question of the sociocultural components of the globalization process, its historical and cultural dimension. As an answer, he proposes his own “minimal phase model” of the sociocultural history of globalization.

An analysis of the universalist concept of the sociocultural history of globalization proposed by Robertson shows that it is built according to the Eurocentric scheme of the “universal history of mankind,” first proposed by the founders of social evolutionism, Turgot and Condorcet. The starting point of Robertson's construction of the world history of globalization is the postulation of the thesis about the real functioning of the “global human condition”, the historical bearers of which successively become societies-nations, individuals, the international system of societies and, finally, all of humanity as a whole. These historical bearers of global human consciousness are formed in the sociocultural continuum of world history, built by Robertson according to the model of the history of ideologies in Europe. The sociocultural history of globalization begins in this model with such a societal unit as the “national society”, or nation-state-society. And here Robertson reproduces the anachronisms of Western European social philosophy, the formation of the central ideas of which is usually linked to the ancient Greek conceptualization of the phenomenon of the city-state (polis). Let us note that the radical transformation of European social and philosophical thought in the direction of its sociologization took place only in modern times and was marked by the introduction of the concept of “civil society” and the concept of “world universal history of mankind.”

Robertson calls his own version of the sociocultural history of globalization a “minimal phase model of globalization,” where “minimal” means that it does not take into account either the leading economic, political and religious factors, or the mechanisms or driving forces of the process under study. And here he, trying to construct a certain world-historical model of human development, creates something that has already appeared for centuries on the pages of textbooks on the history of philosophy as examples of social evolutionism of the 17th century. However, the founders of social evolutionism built their concepts of world history as the history of European thought, achievements in the field of economics, technology and technology, and the history of geographical discoveries.

Robertson identifies five phases of the sociocultural formation of globalization: the embryonic, the initial, the take-off phase, the struggle for hegemony and the uncertainty phase.

First, rudimentary, phase falls on the XV - early XVIII centuries. and is characterized by the formation of European nation states. It was during these centuries that cultural emphasis was placed on the concepts of the individual and humanistic, the heliocentric theory of the world was introduced, modern geography was developed, and the Gregorian calendar was spread.

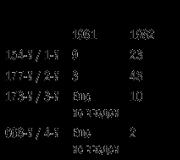

Second, initial, phase begins in the middle of the 18th century. and continues until the 1870s. It is marked by a shift in cultural emphasis towards homogenization and unitary statehood. At this time, the concepts of formalized international relations, the standardized "citizen-individual" and humanity crystallized. According to Robertson, it is this phase that is characterized by the discussion of the problem of accepting non-European societies into international society and the emergence of the topic “nationalism/internationalism”.

Third, phase take off,– since the 1870s. and until the mid-1920s. – includes the conceptualization of “national societies”, the thematization of ideas of national and personal identities, the introduction of some non-European societies into “international society”, the international formalization of ideas about humanity. It is in this phase that an increase in the number and speed of global forms of communication is detected, ecuminist movements, international Olympic Games, Nobel laureates appear, and the Gregorian calendar spreads.

Fourth, phase struggle for hegemony, begins in the 1920s. and ends by the mid-1960s. The content of this phase consists of international conflicts related to the way of life, during which the nature and prospects of humanism are indicated by images of the Holocaust and the explosion of a nuclear bomb.

And finally, the fifth phase uncertainty,– since the 1960s. and further, through the crisis trends of the 1990s, it enriched the history of globalization with the growth of a certain global consciousness, gender, ethnic and racial nuances of the concept of the individual, and the active promotion of the doctrine of “human rights.” The event outline of this phase is limited, according to Robertson, by the landing of American astronauts on the Moon, the fall of the geopolitical system of the bipolar world, the growing interest in global civil society and the global citizen, and the consolidation of the global media system.

The crowning achievement of the sociocultural history of globalization is, as follows from Robertson’s model, the phenomenon of the global human condition. Sociocultural dynamics further development This phenomenon is represented by two directions, interdependent and complementary. The global human condition is developing in the direction of homogenization and heterogeneization of sociocultural patterns. Homogenization is the global institutionalization of the lifeworld, understood by Robertson as the organization of local interactions with the direct participation and control of the world macrostructures of economics, politics and mass media. The global lifeworld is formed and propagated by the media as a doctrine of “universal human values”, which has a standardized symbolic expression and has a certain “repertoire” of aesthetic and behavioral models intended for individual use.

The second direction of development is heterogenesis is the localization of globality, i.e. the routinization of intercultural and interethnic interaction through the inclusion of foreign cultural, “exotic” things in the texture of everyday life. In addition, the local assimilation of global sociocultural patterns of consumption, behavior, and self-presentation is accompanied by the “banalization” of the constructs of the global living space.

Robertson introduces the concept of “glocalization” to capture these two main directions of the sociocultural dynamics of the globalization process. In addition, he considers it necessary to talk about the trends of this process, that is, about the economic, political and cultural dimensions of globalization. And in this context, he calls cultural globalization the processes of global expansion of standard symbols, aesthetic and behavioral patterns produced by Western media and transnational corporations, as well as the institutionalization of world culture in the form of multicultural local life styles.

The above concept of the sociocultural dynamics of the globalization process represents, in essence, an attempt American sociologist depict globalization as a historical process organic to the formation of the human species of mammals. The historicity of this process is justified through a very dubious interpretation of European socio-philosophical thought about man and society. The vagueness of the main provisions of this concept and the weak methodological elaboration of the central concepts served, however, to the emergence of a whole direction of discourse about global culture, aimed primarily at scientifically reliable substantiation of the ideologically biased version of globalization.

15.3. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization

The concept of “cultural dynamics of globalization,” proposed by P. Berger and S. Huntington, ranks second in terms of authority and frequency of citation in the international cultural and sociological discussion about the cultural fate of globalization. According to its creators, it is aimed at identifying the “cultural parameters of globalization.” The modeling of these parameters is based on a methodological trick well developed by Berger and Huntington in their previous theorizing experience. The concept of “global culture” is built in accordance with scientifically established criteria for classifying a particular phenomenon of social life as a fact of sociocultural reality. Thus, Berger and Huntington state that the starting point for their concept is the very concept of “culture,” defined in the generally accepted social scientific sense of the word, that is, as “the beliefs, values and way of life of ordinary people in their everyday existence.” And then the discourse unfolds according to a standard algorithm for cultural studies, cultural anthropology and sociology: the historical and cultural prerequisites of this culture, its elite and popular levels of functioning, its bearers, spatiotemporal characteristics, and dynamics of development are revealed. The methodological trick performed by Berger and Huntington is that the development of the concept of global culture and the corresponding proof of its legitimacy are replaced by the definition of the concept “culture” established in the socio-humanitarian sciences, which has nothing in common either with the discourse about globalization or with the phenomenon of globalization itself.

The hypnotic consequence of this illusionistic technique is manifested in the instant immersion of the professional reader into the abyss of political science essays and a quasi-definition of global culture. Real facts and events of our time, linked into a single whole by the distinct logic of the world economy and politics, are presented as representatives of global culture.

Global culture, according to Berger and Huntington, is the fruit of the “Hellenistic stage of development of Anglo-American civilization.” Global culture is American in its genesis and content, but at the same time, in the paradoxical logic of the authors of the concept, it is in no way connected with the history of the United States. Moreover, Berger and Huntington insist that the phenomenon of global culture cannot be explained using the concept of “imperialism.” The main factor in its emergence and planetary spread should be considered the American English language - the final world-historical stage of the Anglo-American civilization. This new Koine, being the language of international communication (diplomatic, economic, scientific, tourist, interethnic), transmits the “cultural layer of cognitive, normative and even emotional contents” of the new civilization.

The emerging global culture, like any other culture, reveals, according to the vision of Berger and Huntington, two levels of its functioning - elite and popular. Its elite level is represented by the practices, identities, beliefs and symbols of international business and clubs of international intellectuals. The popular level is the culture of mass consumption.

The content of the elite level of global culture consists of “Davos culture” (Huntington’s term) and the club culture of Western intellectuals. Its bearers are “communities of ambitious young people engaged in business and other activities” whose life goal is to be invited to Davos (the Swiss international mountain resort where high-level economic consultations are held annually). In the “elite sector” of global culture, Berger and Huntington also include the “Western intelligentsia”, which creates the ideology of global culture, embodied in the doctrine of human rights, the concepts of feminism, protection environment and multiculturalism. The ideological constructs produced by the Western intelligentsia are interpreted by Berger and Huntington as normative rules of behavior and generally accepted ideas of global culture, inevitably subject to assimilation by all those who want to succeed “in the field of elite intellectual culture.”

Anticipating possible questions from non-Western intellectuals, Berger and Huntington repeatedly emphasize that the main bearers of the emerging global culture are Americans, and not some “cosmopolitans with parochial interests” (the concept of J. Hunter, who made sharp scientific criticism of the term “global intellectual”). All others, non-American businessmen and intellectuals, must for now only be content with the hope of becoming involved in global culture.

The popular popular level of global culture is the mass culture promoted by Western commercial enterprises, mainly trade, food and entertainment (Adidas, McDonald, McDonald's Disney, MTV etc.). Berger and Huntington consider the “broad masses” of consumers to be the carriers of mass culture. Berger proposes to rank the media of mass culture in accordance with the criterion of “participatory and uninvolved consumption.” This criterion, in Berger’s deep conviction, helps to identify the chosenness of some and the complete non-involvement of others, since “participatory consumption” in his interpretation is “a sign of invisible grace.” Thus, involvement in the consumption of values, symbols, beliefs and other Western mass culture is presented in this concept as a sign of God's chosenness. Uninvolved consumption implies the “banalization” of consumption, a malicious skimping on reflection on its deep symbolic sense. According to Berger, consumption devoid of divine grace is the use of mass culture products for their intended purpose, when eating hamburgers and wearing jeans becomes commonplace and loses its original meaning of joining the lifestyle of the elect, to some kind of grace.

Mass culture, according to Berger and Huntington, is introduced and spread through the efforts of mass movements of various types: movements of feminists, environmentalists, and human rights activists. A special mission is given here to evangelical Protestantism, since “conversion to this religion changes people’s attitudes towards family, sexual behavior, raising children and, most importantly, towards work and the economy in general.” At this point in his argument, Berger, using his international authority as a professional sociologist of religion with a high citation index, is essentially trying to impose on researchers the idea that evangelical Protestantism is the religion of the elect, the religion of a global culture designed to radically change the image of the world and the identity of humanity.

It is evangelical Protestantism, in the concept of Berger and Huntington, that embodies the “spirit” of a global culture aimed at cultivating the masses ideals of personal self-expression, gender equality and the ability to create voluntary organizations. According to Berger and Huntington, the ideology of global culture should be considered individualism, which helps to destroy the dominance of tradition and the spirit of collectivism, to realize the ultimate value of global culture - personal freedom.

In the concept of Berger and Huntington, global culture is not only historical as the Hellenistic stage of the Anglo- American culture, but also clearly fixed in space. It has centers and peripheries, represented respectively by metropolises and regions dependent on them. Berger and Huntington do not consider it necessary to go into a detailed explanation of the thesis about the territorial attachment of global culture. They limit themselves only to clarifying that the metropolis is a space for consolidating an elite global culture, and its business sector is located in both Western and Asian giant cities, and its intellectual sector is based only in the metropolitan centers of America. Berger and Huntington leave the spatial characteristics of global folk culture without comment, because it is destined to take over the whole world.

And finally, the final conceptual component of this theorizing is the dynamics of the development of global culture. And here Berger and Huntington consider it necessary to reinterpret the concept of “glocalization,” which is basic for the first direction of interpretation of the sociocultural dynamics of globalization. Unlike most of their colleagues in the ideologically biased construction of globalization, Berger and Huntington prefer to talk about “hybridization,” “alternative globalization,” and “subglobalization.” The combination of these three trends in the development of globalization forms the sociocultural dynamics of globalization in their concept.

The first trend of hybridization is understood as the deliberate synthesis of Western and local cultural characteristics in business, economic practices, religious beliefs and symbols. This interpretation of the processes of introducing ideologies and practices of global culture into the texture of national traditions is based on the gradation of cultures into “strong” and “weak” proposed by Huntington. Huntington calls strong cultures all those that are capable of “creative adaptation of culture, that is, of processing samples of American culture based on their own cultural tradition" He classifies the cultures of the countries of East and South Asia, Japan, China and India as strong, and African cultures and some cultures of European countries as weak. At this point in their reasoning, Berger and Huntington openly demonstrate the political and ideological bias of the concept they put forward. The term “hybridization” is ideological in its essence; it refers to non-discursive, axiological postulates about the chosenness of some cultures and the complete worthlessness of others. Behind this interpretation lies both the chosenness of peoples, preached by Berger, and the inability of cultures to be creative, defined by Huntington. Hybridization is not a trend, but a deliberate geopolitical project of a game of survival.

The second trend in the dynamics of global culture is alternative globalization, defined as global cultural movements that arise outside the West and have a strong influence on it. This trend indicates, according to Berger and Huntington, that modernization, which gave rise to the Western model of globalization, represents an obligatory stage in the historical development of all countries, cultures and peoples. Alternative globalization, therefore, is a historical phenomenon of non-Western civilizations that have reached the stage of modernity in their development. Berger and Huntington believe that these other models of globalization, like Anglo-American global culture, have an elite and popular level of functioning. It was among the non-Western elite that secular and religious movements of alternative globalization arose. However, practical influence on the way of life of the dominant global culture in the world can only be exerted by those who promote a modernity that is alternative to national cultural traditions - a modernity that is democratic and devoted to Catholic religious and moral values.

From the above characteristics of the second trend in the dynamics of the development of global culture, it clearly follows that it is called “alternative” only because it runs counter to national historical and cultural traditions, contrasting them with the same American values of modern Western society. Quite surprising from a cultural point of view are the examples chosen by Berger and Huntington to illustrate non-Western cultural movements of alternative globalization. In number prominent representatives non-Western global culture they included a Catholic organization Opus Dei, originated in Spain, the Indian religious movements of Sai Baba, Hare Krishna, the Japanese religious movement Soka Gakkai, the Islamic movements of Turkey and the New Age cultural movements. It should be noted that these movements are heterogeneous in their genesis and preach completely different religious and cultural patterns. However, in the interpretation of Berger and Huntington, they appear as a united front of fighters for a consistent synthesis of the values of Western liberalism and certain elements of traditional cultures. Even a superficial, scientifically motivated examination of the examples of “alternative globalization” proposed by Berger and Huntington shows that all of them in reality represent a radical counterexample to the theses stated in their concept.

The third trend of “subglobalization” is defined as “movements that have a regional scope” and contribute to the rapprochement of societies. Berger and Huntington's illustrations of subglobalization include the "Europeanization" of post-Soviet countries, Asian media modeled after Western media, men's "colorful shirts with African motifs" (Mandela shirts). Berger and Huntington do not consider it necessary to reveal the historical genesis of this trend or consider its content, since they believe that the listed elements of subglobalization are not part of global culture, but only act as “intermediaries between it and local cultures.”

The concept of “cultural parameters of globalization” proposed by Berger and Huntington is a striking example of the methodology for ideological modeling of the phenomenon of globalization. This concept, declared as scientific and developed by authoritative American scientists, is, in fact, the imposition of an unusual direction of geopolitical programming on the cultural discourse, an attempt to pass off an ideological model as a scientific discovery.

15.4. Global culture and cultural “expansion”

A fundamentally different direction of cultural and sociological understanding of globalization is represented in the international discussion by the concepts of E. D. Smith and A. Appadurai. The phenomenon of global culture and the accompanying processes of globalization of cultures and cultural globalization are interpreted within the framework of this direction as ideological constructs derived from the real functioning of the world economy and politics. At the same time, the authors of these concepts make an attempt to comprehend the historical prerequisites and ontological foundations for the introduction of this ideological construct into the texture of everyday life.

The concept of global culture proposed by Anthony D. Smith is built through the methodological and substantive opposition of the scientifically based concept of “culture” to the image of “global culture”, ideologically constructed and promoted by the media as a reality on a global scale. Unlike Robertson, the founder of the discourse on globalization, Smith does not call for thinking scientific world abandon the concept of culture due to the need to build a sociological or cultural interpretation of the processes of globalization. Moreover, the initial methodological thesis of his concept is the postulation of the fact that the socio-humanitarian sciences have a completely clear definition of the concept of “culture”, conventionally accepted in discourse and not subject to doubt. Smith points out that the diversity of concepts and interpretations of culture invariably reproduces its definition as “a collective way of life, a repertoire of beliefs, styles, values and symbols” enshrined in the history of societies. The concept of “culture” is conventional in the scientific sense of the word, since in historical reality we can only talk about cultures that are organic to social time and space, the territory of residence of a particular ethnic community, nation, people. In the context of such a methodological thesis, the very idea of “global culture” seems absurd to Smith, since it refers the scientist to some kind of comparison of an interplanetary nature.

Smith emphasizes that even if we try, following Robertson, to think of global culture as a kind of artificial environment of the human mammalian species, then in this case we will find striking differences in the lifestyles and beliefs of segments of humanity. In contrast to supporters of the interpretation of the process of globalization as historically natural, culminating in the emergence of the phenomenon of global culture, Smith believes that from a scientific point of view it is more justified to talk about ideological constructs and concepts that are organic to European societies. Such ideological constructs are the concepts of “national states”, “transnational cultures”, “global culture”. It is these concepts that were generated by Western European thought in its aspirations to build a certain universal model of the history of human development.

Smith contrasts the model of sociocultural history of globalization put forward by Robertson with a very laconic overview of the main stages in the formation of the European-American ideologeme with the transnationality of human culture. In his conceptual review, he clearly demonstrates that the ontological basis of this ideologeme is the cultural imperialism of Europe and the United States, which is an organic consequence of the truly global economic and political claims of these countries to universal dominance.

The sociocultural dynamics of the formation of the image of global culture are interpreted by Smith as the history of the formation of the ideological paradigm of cultural imperialism. And in this history he identifies only two periods, marked respectively by the emergence of the very phenomenon of cultural imperialism and its transformation into a new cultural imperialism. By cultural imperialism Smith means the expansion of ethnic and national “sentiments and ideologies—French, British, Russian, etc.” to a universal scale, imposing them as universal human values and achievements of world history.

Smith begins his review of the concepts developed in the original cultural imperialism paradigm by pointing out the fact that before 1945 it was still possible to believe that the “nation-state” was a normative social organization modern society, designed to embody the humanistic idea of national culture. However, the Second World War put an end to the perception of this ideologeme as a universal humanistic ideal, demonstrating to the world the large-scale destructive capabilities of the ideologies of “supernations” and dividing it into winners and losers. The post-war world put an end to the ideals of the nation state and nationalism, replacing them with a new cultural imperialism of “Soviet communism, American capitalism and new Europeanism.” Thus, the time frame of initial cultural imperialism in Smith’s concept is the history of European thought from antiquity to modern times.

According to Smith, the next ideological and discursive stage of cultural imperialism is the “era of post-industrial society.” Its historical realities were economic giants and superpowers, multinationality and military blocs, superconducting communication networks and the international division of labor. The ideological orientation of the paradigm of cultural imperialism of “late capitalism, or post-industrialism” assumed a complete and unconditional rejection of the concepts of small communities, ethnic communities with their right to sovereignty, etc. The humanistic ideal in this paradigm of understanding sociocultural reality is cultural imperialism, based on economic, political and communicative technologies and institutions.

A fundamental characteristic of the new cultural imperialism was the desire to create a positive alternative to “national culture”, the organizational basis of which was the nation-state. It was in this context that the concept of “transnational cultures,” depoliticized and not limited to the historical continuum of specific societies, arose. The new global imperialism, which has economic, political, ideological and cultural dimensions, offered the world an artificially created construct of global culture.

According to Smith, global culture is eclectic, universal, timeless, and technical—a “constructed culture.” It is deliberately constructed in order to legitimize the globalizing reality of economies, politics and media communications. Its ideologists are countries that promote cultural imperialism as a kind of universal humanistic ideal. Smith points out that attempts to prove the historicity of global culture through an appeal to the fashionable modern concept of “constructed communities” (or “imagined communities”) do not stand up to criticism.

Indeed, the ideas of an ethnocommunity about itself, the symbols, beliefs and practices that express its identity are ideological constructs. However, these designs are enshrined in the memory of generations, in the cultural traditions of specific historical communities. Cultural traditions as historical repositories of identity constructs create themselves, organically consolidating themselves in space and time. These traditions are called cultural because they contain constructs of collective cultural identity - those feelings and values that symbolize the duration of the common memory and image of the common fate of a particular people. Unlike the ideologeme of global culture, they are not brought down from above by some globalist elite and cannot be written or erased by its will. tabula rasa(Latin – blank slate) of a certain humanity. And in this sense, the attempt of globalization apologists to legitimize the ideologeme of global culture in the status of a historical construct modern reality absolutely barren.

Historical cultures are always national, particular, organic to a specific time and space, the eclecticism allowed in them is strictly determined and limited. Global culture is ahistorical, does not have its own sacred territory, does not reflect any identity, does not reproduce any common memory of generations, and does not contain prospects for the future. Global culture does not have historical carriers, but it has a creator - a new cultural imperialism of global scope. This imperialism, like any other - economic, political, ideological - is elitist and technical, and does not have any popular level of functioning. It was created by those in power and is imposed on the “simple people” without any connection with those folk cultural traditions of which these “simple people” are the bearers.

The concept discussed above is aimed primarily at debunking the authoritative scientific myth modernity about the historicity of the phenomenon of global culture, the organic nature of its structure and functions. Smith consistently argues that global culture is not a construct of cultural identity, it does not have a popular level of functioning characteristic of any culture, and it does not have elite carriers. The levels of functioning of global culture are represented by an abundance of standardized goods, a jumble of denationalized ethnic and folk motifs, a series of generalized “human values and interests,” a homogeneous, emasculated scientific discourse about meaning, and the interdependence of communication systems that serve as the basis for all its levels and components. Global culture is the reproduction of cultural imperialism on a universal scale; it is indifferent to specific cultural identities and their historical memory. The main ontological obstacle to the construction of global identity, and therefore global culture, Smith concludes, is historically fixed national cultures. In the history of mankind it is impossible to find any common collective memory, and the memory of the experience of colonialism and the tragedies of world wars is a history of evidence of the split and tragedies of the ideals of humanism.

The theoretical and methodological approach proposed by A. Appadurai is formulated taking into account the disciplinary framework of sociology and anthropology of culture and on the basis of sociological concepts of globalization. A. Appadurai characterizes his theoretical approach as the first attempt at a socio-anthropological analysis of the phenomenon of “global culture”. He believes that the introduction of the concept of “global cultural economy” or “global culture” is necessary to analyze the changes that occurred in the world in the last two decades of the 20th century. Appadurai emphasizes that these concepts are theoretical constructs, a kind of methodological metaphor for the processes that generate a new image of the modern world within the globe. The conceptual scheme he proposed thus claims, first of all, to be used to identify and analyze the meaning-forming components of reality, which is designated by modern sociologists and anthropologists as a “single social world.”

In his opinion, the central factors of the changes sweeping the whole world are electronic communications and migration. It is these two components of the modern world that transform it into a single space of communication across state, cultural, ethnic, national and ideological boundaries and despite them. Electronic means of communication and constant flows of migration of various kinds of social communities, cultural images and ideas, political doctrines and ideologies deprive the world of historical extension, placing it in the mode of a constant present. It is through the media and electronic communications that various images and ideas, ideologies and political doctrines are combined into a new reality, devoid of the historical dimension of specific cultures and societies. Thus, the world in its global dimension appears as a combination of flows of ethnocultures, images and sociocultural scenarios, technologies, finance, ideologies and political doctrines.

The phenomenon of global culture, according to Appadurai, can be studied only if we understand how it exists in time and space. In terms of the unfolding of global culture in time, it represents the synchronization of the past, present and future of various local cultures. The merging of three modes of time into a single extended present of global culture becomes real only in the dimension of the modernity of the world, developing according to the model of civil society and modernization. In the context of the global modernization project, the present of developed countries (primarily America) is interpreted as the future of developing countries, thereby placing their present in a past that has not yet taken place in reality.

Speaking about the space of functioning of global culture, Appadurai points out that it consists of elements, “shards of reality”, connected through electronic means of communication and mass media into a single constructed world, which he denotes by the term “scape”. The term “scape” is introduced by him to indicate the fact that the global reality under discussion is not given in the objective relations of international interactions of societies and nation-states, ethnic communities, political and religious movements. It is “imagined”, constructed as that common “cultural field” that knows no state borders, is not tied to any territory, and is not limited to the historical framework of the past, present or future. An elusive, constantly moving unstable space of identities, combined cultural images, ideologies without time and territorial boundaries - this is “scape”.

Global culture is seen by Appadurai as consisting of five constructed spaces. It is a constantly changing combination of interactions between these spaces. So, global culture appears, Appadurai believes, in its following five dimensions: ethnic, technological, financial, electronic and ideological. Terminologically they are designated as ethnoscape, technoscape, financialscape, mediascape and ideoscape.

The first and fundamental component of global culture– ethnoscape is the constructed identity of various kinds of migrating communities. Migrating flows of social groups and ethnic communities include tourists, immigrants, refugees, emigrants, and foreign workers. It is they who form the space of the “imaginary” identity of global culture. The common characteristic of these migrating people and social groups is permanent movement in two dimensions. They move in the real space of the world of territories that have state borders. The starting point of such a movement is a specific locus—a country, a city, a village—designated as the “homeland,” and the final refuge is always temporary, conditional, and impermanent. The difficulty of establishing the final destination, locus, and territory of these communities is due to the fact that the limit of their activity is returning to their homeland. The second dimension of their permanent movement is movement from culture to culture.

The second component of global culture– technoscape is a flow of outdated and modern, mechanical and information technologies, forming a bizarre configuration of the technical space of global culture.

Third component– financialscape is an uncontrollable flow of capital, or a constructed space of money markets, national exchange rates and goods that exist in movement without borders in time and space.

The connection between these three components of global culture, functioning in isolation from each other, is mediated by the unfolding of the space of images and ideas (mediascape), produced by the mass media and legitimized through the space of constructed ideologies and political doctrines (ideoscape).

The Fourth Component of Global Culture– mediascapes are vast and complex repertoires of images, narratives and “imaginary identities” generated by the media. The constructed space of a combination of the real and the imaginary, mixed reality, can be addressed to any audience in the world.

Fifth component– ideoscape is a space created by political images associated with the ideology of states. This space is made up of such “fragments” of ideas, images and concepts of the Enlightenment as freedom, well-being, human rights, sovereignty, representation, democracy. Appadurai notes that one of the elements of this space of political narratives – the concept of “diaspora” – has lost its internal substantive specificity. The definition of what a diaspora is is highly contextual and varies from one political doctrine to another.

Appadurai believes that one of the the most important reasons The globalization of culture in the modern world is “deterritorialization”. “Deterritorialization” leads to the emergence of the first and most important dimension of “global culture” - the ethnoscape, i.e. tourists, immigrants, refugees, emigrants and foreign workers. Deterritorialization causes the emergence of new identities, global religious fundamentalism, etc.

The concepts of “global culture”, “constructed ethnic communities”, “transnational”, “local”, introduced as part of the discussion of sociologists and anthropologists on globalization, served as a conceptual scheme for a number of studies on the new global identity. In the context of this discussion, the problem of studying ethnic minorities, religious minorities that emerged only at the end of the 20th century, and their role in the process of constructing the image of global culture can be posed in a completely new way. In addition, the concept proposed by Appadurai provides grounds for scientific study of the problem of a new global institutionalization of world religions.

- 1) the transformation of the planet into a “global village” (M. McLuhan), when millions of people, thanks to the media, almost instantly become witnesses to events taking place in different parts of the globe;

- 2) introducing people living in different countries and on different continents to the same cultural experience (Olympiads, concerts);

- 3) unification of tastes, perceptions, preferences (Coca-Cola, jeans, soap operas);

- 4) direct acquaintance with the way of life, customs, and norms of behavior in other countries (through tourism, work abroad, migration);

- 5) the emergence of the language of international communication - English;

- 6) widespread distribution of unified computer technology, Internet;

- 7) “erosion” of local cultural traditions, their replacement with mass consumer culture of the Western type

Firstly, in the modern world, as practice has shown, the only possible way of interaction between cultures is their dialogue, i.e. equal partnership. Meanwhile, globalization today acts as the spread of those principles that determine the specifics of the development of the Western world.

Secondly, globalization today it acts as a dissemination primarily of North American culture. This allows some researchers to say that globalization (at least in Russia) comes in the form of Americanization. Today, in practice, globalization actually means the transformation of a large part of the world into a kind of Pax Americana with standardized image and ideals of life, forms of political organization of society, life values and type of mass culture .

The third trend accompanying the formation of a monocultural world is a sharp decline in the status and area of competence of the national states with its economy, socio-political structures, culture. The ongoing regionalization within the global system has deprived the state of its monopoly on power.

Fourth trend monopolarization of the world is associated with destruction traditions, disappearance of customs and rituals, recording and broadcasting a certain picture of the world, testifies to the disintegration of an entire system of ideas, values, and social connections, which constitute the uniqueness of each national culture. In addition, these processes are inevitably accompanied by the destruction of traditional mechanisms of production and distribution. cultural values, i.e. culture loses its ability to reproduce itself.

Fifth is a change in the relationship between high specialized, folk and mass culture, where the latter undoubtedly dominates. Mass culture in the processes of globalization acts as a universal cultural project, the basis of an emerging transnational culture, and in this sense it becomes a tool for the destruction of national cultural traditions, a mechanism of cultural expansion

The sixth significant trend accompanying the formation of a monocultural world is disintegration of natural connections in culture and disruption of identification mechanisms. This is expressed in a crisis of national, political, religious, and cultural identity, when a person loses the ability to compare his image of the world with the generally accepted one within an ethnic group, nation, state, class or any other community.

Destruction national and ethnic identity leads to the formation of new identities based on different principles of self-identification.

In the 60s M. McLuhan predicted the unification of humanity with the help of the Quality Management System into a “global village”. Today, the number of new social structures is increasing, becoming the most powerful unifying factor in a situation of total disintegration. In this regard, the task becomes of great importance preservation of national-state identity. This special treatment to traditional culture and traditional values, expressed both legislatively and financially in the form of purposefully allocated funds

If speak about political-cultural identity, then in post-war period(and before the collapse of the USSR) in developed capitalist countries it was characterized by the idea of a “free West”, in second world countries - in terms of socialism, in third world countries - in terms of “development”. Established during the era cold war“The certainty of political-cultural identity was destroyed. Today, as N. Stevenson notes, it is being replaced by the phenomenon of so-called “cultural citizenship”, based on community of consumption. Today, citizenship, as the author notes, turns out to be less associated with formal rights and responsibilities and more with the consumption of exotic products, Hollywood films, popular music or Australian wines.

Concerning religious identity, then two trends can be distinguished here. According to R. Sellers, the first trend is the growing struggle between religiosity and atheism. The second is the phenomenon of religious syncretism, the desire to attend more than one church (for example, in North America this is 9% of Americans).

Seventh trend, accompanying the unification of culture, is essential transformation of national specific thinking under the influence of a unified English-language newspeak. Today, the spread of the English language is becoming a condition for the spread of a universal way of life. English language used today as a means of communication by about 1.5 billion people

Meanwhile, language is a way of preserving and transmitting the culture, traditions and social identity of a given speech group, ethnic group and nation. The eighth trend in cultural development in the global world is a combination of scientific- technical progress, the highest embodiment of which was the era of electronic-network communications, with the process of negative development of sociality. This manifests itself in the lag of the human factor from the development of information technology. The reason here is primarily the difference in levels of information possession, and the main principle of inequality is the inequality of knowledge possession.

But knowledge and information itself today are becoming the highest values of society not as tools for comprehending the truth, but as tools for realizing all needs.

So, the question of the globalization of culture is much more complex than the question of the globalization of the economic, political and financial sphere. First of all, this is determined by the fact that such components of spiritual culture as values, meanings and meanings, the picture of the world, the nature of the symbolic objectification of the world, do not obey the laws of progress and do not lend themselves to unification, generalization and mechanical combination, as the neo-Kantians noted. If this happens, we can talk not about the globalization of, say, values, but about the replacement of some values and the corresponding cultural worlds with others, about the absorption of one picture of the world, one symbolic system by another.

Globalization occurs not only in the economic sphere, but also in the field of culture and information. The production of information has become in our time the main source of development, including economic development. Information today has covered the whole world with its networks and flows.

In the information world, a person engaged in production is required to do more than just business activity and diligence.

He now needs constant access to sources of information and must be able to use it. The social wealth of a country is now measured not only by its natural resources and the volume of finances, but also the level of awareness of the population in the field of new ideas and technologies, their education, intellectual development, and the presence of their creative potential. In the overall structure of this wealth, the importance of cultural capital increases immeasurably compared even to natural and economic wealth.

It is obvious that the only model of globalization acceptable to world public opinion is one that provides peoples with equal chances to participate in this process and enjoy its fruits while preserving their national and cultural identity. Only such a model will be accepted by the people voluntarily, and not imposed on them by force. A system that gives advantages to some at the expense of others, or creates preferential conditions for some particular system of cultural norms and images, will not be accepted.