The composition of the story "Woe from Wit". The plot and compositional originality of A.S.’s comedy

2 lessons

Lesson objectives: introduce students to the bright personality of A.S. Griboedov, expand knowledge about comedy, learn to analyze the list of characters, comment on the first act of Griboyedov’s comedy “Woe from Wit”, identify the features of the construction of the comedy exposition, analyze other actions, identify features of the conflict, reveal the main stages of the plot

DURING THE CLASSES:

A story about the life of A.S. Griboyedov (presentation)

The history of comedy (according to the textbook)

A) Analysis of the list of actors

Famusov (from Latin Fama - rumor)

Repetilov (from the French Repetet - repeat)

Molchalin, Skalozub, Tugoukhovsky, Khryumina, Khlestova and others

The surname Chatsky carries an encrypted hint to the name of one of most interesting people era - Pyotr Yakovlevich Chaadaev. In some draft versions, Griboyedov called his hero Chadsky.

Pyotr Yakovlevich Chaadaev graduated from the verbal department of the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow University (1811). He took part in the Patriotic War of 1812, in the foreign “anti-Napoleonic” campaign. In 1814 he joined Masonic lodge, and in 1821 suddenly interrupted the brilliant military career and agreed to join a secret society. After retiring, he did a lot of self-education and turned to religion and philosophy. Lived abroad (1823-1826), met many philosophers. In 1836, Chaadaev’s “Philosophical Letter” was published in the Telescope magazine. The harsh criticism it contained of Russia's past and present caused a shock effect in society. The reaction of the authorities was harsh: the magazine was closed, Chaadaev was declared crazy. He was under police and medical supervision for more than a year. Then the surveillance was lifted, and Chaadaev returned to the intellectual life of Moscow society.

It so happened that the literary character did not repeat the fate of his prototype, but predicted it

B)

Working with 1 act comedy

1. Viewing the 1st act of the play “Woe from Wit”

2. Commented reading with elements of analysis

How does a comedy begin? (morning, Lisa sets the clock, bothers Molchalin and Sofia; Famusov flirts with Lisa)

How do the heroes behave? (everyone lies, trying to hide something)

What two opinions about Chatsky does the reader learn before his appearance? (Lisa’s opinion: “... sensitive and cheerful, and witty”; Sophia’s opinion: “... knows how to make everyone laugh nicely”)

How does Chatsky behave on his first date with Sophia? Why ? (Chatsky is excited, tense, he has been waiting for this meeting for a long time)

How does Sophia behave when she sees Chatsky? (Sofya is reserved, moderately polite, because a lot of time has passed since Chatsky left, and now she is passionate about Molchalin)

Chatsky’s monologues “And sure enough, the world began to grow stupid...”, “Who are the judges?”

Famusov’s monologues “That’s it, you are all proud!”, “Taste, father, excellent manners”

Who is Skalozub? Could Sophia like him?

Does Sofya love Molchalina? And he hers? What new do we learn about the character of the hero from this action?

How does the “in love” Chatsky behave?

Working with 3rd action

For what purpose is Chatsky going to the ball at Famusov’s house? (get Sophia to confess who she loves)

Has Chatsky changed? How do you see him at the ball?

How does Sophia greet him? (Sophia likes Molchalin, but Chatsky criticizes him)

Why is everyone picking up the gossip about Chatsky’s madness? (gossip connects love and social conflict s. On the one hand, the hero behaves as if he has gone crazy with love, on the other hand, his behavior is regarded as social madness)

Working with 4th action

Features of the composition

What is comedy?

What is conflict in a dramatic work?

What was the conflict in the traditional drama of classicism? (love)

Is there a love conflict in the comedy "Woe from Wit"?

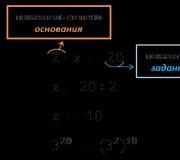

Love conflict. Main stages of development (composition)

Exposition– morning in Famusov’s house; everyone lies, trying to hide something (it is important for the writer to show the atmosphere in Famusov’s house, the peculiarities of relationships in the family)

The beginning of the conflict- Sophia’s words to Chatsky’s unflattering review of Molchalin (“Not a man - a snake”)

Climax– the scene of Molchalin falling from a horse and Sophia’s reaction – fainting

Resolution of the conflict- scene of Molchalin explaining his life position Lisa under the stairs, Chatsky and Sophia hear this conversation

Is love conflict the main one? driving force comedy? (the love conflict is not the main one, since Griboedov set the goal not just to show the nature of the characters’ love relationships, but to reveal the morals of contemporary Moscow, to show the emerging contradictions in society)

What is the main conflict in comedy? (socio-political as a reflection of all the contradictions of that time)

Which of the comedy heroes is involved in a socio-political conflict? (Chatsky and representatives Famusov society)

Socio-political conflict. Main stages of development (composition)

The beginning- a conversation between Chatsky and Famusov, in which Famusov sets out his morality;

Climax- a scene at the ball, when Chatsky is indignant, outraged, pronounces his accusatory monologues, and “... everyone is spinning in the waltz with the greatest zeal. The old men scattered to the card tables;

Denouement- Chatsky’s departure, but the conflict is not completely resolved, the ending is open.

What is the essence of the socio-political conflict? (conflict between an intelligent person and a vulgar crowd)

Work with text

Write down catch phrases

Write out the main characteristics of the heroes from the text

Result: There are two main conflicts in the comedy: the love one, with which the play begins, gradually develops into a social one, when the “present century” and the “past century” are contrasted. The social conflict turns out to be broader and does not fit into the framework of a love plot.

The plot of Griboyedov's comedy in itself is already quite original and unusual. I cannot agree with those who consider it banal. At first glance, it may seem that the main plot is the love story of Chatsky for Sophia. Indeed, this story occupies the work great place, giving liveliness to the development of action. But still, the main thing in comedy is Chatsky’s social drama. The title of the play indicates this. The story of Chatsky's unhappy love for Sophia and the story of his conflict with the Moscow nobility, closely intertwined, are combined into a single plot line. Let's follow its development. The first scenes, morning in Famusov's house - an exposition of the play. Sophia, Molchalin, Liza, Famusov appear, the appearance of Chatsky and Skalozub is prepared, the characters and relationships of the characters are described. The movement and development of the plot begins with the first appearance of Chatsky. And before this, Sophia spoke very coldly about Chatsky, and now, when he, animatedly sorting through his Moscow acquaintances, laughed at Molchalin at the same time, Sophia’s coldness turned into irritation and indignation: “Not a man, a snake!” So Chatsky, without suspecting it, turned Sophia against himself. Everything that happened to him at the beginning of the play will receive further continuation and development: he will be disappointed in Sophia, and his mocking attitude towards his Moscow acquaintances will grow into a deep conflict with Famus society. From Chatsky’s dispute with Famusov in the second act of the comedy, it is clearly clear that this is not just a matter of dissatisfaction with each other. Here two worldviews collided.

In addition, in the second act, Famusov’s hints about Skalozub’s matchmaking and Sophia’s fainting pose Chatsky with a painful riddle: could Sophia’s chosen one really be Skalozub or Molchalin? And if this is so, then which one of them?.. In the third act the action becomes very intense. Sophia unambiguously makes it clear to Chatsky that she does not love him and openly admits her love for Molchalin, but she says about Skalozub that this is not the hero of her novel. It seems that everything has become clear, but Chatsky does not believe Sophia. This disbelief strengthens in him even more after a conversation with Molchalin, in which he shows his immorality and insignificance. Continuing his sharp attacks against Molchalin, Chatsky arouses Sophia’s hatred of himself, and it is she, first by accident, and then intentionally, who starts a rumor about Chatsky’s madness. The gossip is picked up, spreads with lightning speed, and they begin to talk about Chatsky in the past tense. This is easily explained by the fact that he has already managed to turn not only the hosts, but also the guests against himself. Society cannot forgive Chatsky for protesting against his morality.

This is how the action reaches highest point, climax. The denouement comes in the fourth act. Chatsky learns about the slander and immediately observes the scene between Molchalin, Sophia and Liza. “Here is the solution to the riddle at last! Here I am sacrificed to someone!” - this is the final insight. With enormous internal pain, Chatsky pronounces his last monologue and leaves Moscow. Both conflicts are brought to an end: the collapse of love becomes obvious, and the clash with society ends in a break.

Discussing the clarity and simplicity of the composition of the play, V. Kuchelbecker noted: “In “Woe from Wit” ... the whole plot consists of Chatsky’s opposition to other persons; ... here ... there is no what in drama is called intrigue. Dan Chatsky ", other characters are given, they are brought together, and it is shown what the meeting of these antipodes must necessarily be like - and nothing more. It is very simple, but in this simplicity there is news, courage "... The peculiarity of the composition "Woe from Wit" in the fact that its individual scenes and episodes are connected almost arbitrarily. It is interesting to see how, with the help of the composition, Griboedov emphasizes Chatsky’s loneliness. At first, Chatsky sees with disappointment that his former friend Platon Mikhailovich “has become the wrong person” in a short time; Now Natalya Dmitrievna directs his every move and praises him with the same words that Molchalin later praises the Pomeranian: “My husband is a wonderful husband.” So, Chatsky’s old friend turned into an ordinary Moscow “husband - boy, husband - servant.” But this is not a very big blow for Chatsky. Nevertheless, throughout the entire time when the guests arrive at the ball, he talks with Platon Mikhailovich. But Platon Mikhailovich later recognizes him as crazy and, for the sake of his wife and everyone else, abandons him. Further on, Griboyedov, in the middle of his fiery monologue, first addressed to Sophia, Chatsky looks back and sees that Sophia has left without listening to him, and in general “everyone is spinning in the waltz with the greatest zeal. The old people have scattered to the card tables.” And finally, Chatsky’s loneliness is especially acutely felt when Repetilov begins to force himself on him as a friend, starting a “sensible conversation... about vaudeville.” The very possibility of Repetilov’s words about Chatsky: “He and I... we have... the same tastes” and a condescending assessment: “he’s not stupid” shows how far Chatsky is from this society, if he no longer has anyone to talk to , except for the enthusiastic chatterbox Repetilov, whom he simply cannot stand.

The theme of falling and the theme of deafness runs through the entire comedy. Famusov recalls with pleasure how his uncle Maxim Petrovich fell three times in a row to make Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna laugh; Molchalin falls from his horse, tightening the reins; Repetilov stumbles, falls at the entrance and “hastily recovers”... All these episodes are interconnected and echo the words of Chatsky: “And he was completely confused, and fell so many times”... Chatsky also falls to his knees in front of Sophia, who no longer loves him. The theme of deafness is also constantly and persistently repeated: Famusov covers his ears so as not to hear Chatsky’s seditious speeches; the universally respected Prince Tugoukhovsky does not hear anything without a horn; Khryumina, the Countess-grandmother, herself completely deaf, having heard nothing and having mixed up everything, edifyingly says: “Oh! Deafness is a great vice.” Chatsky and later Repetilov hear no one and nothing, carried away by their monologues.

There is nothing superfluous in “Woe from Wit”: not a single unnecessary character, not a single unnecessary scene, not a single wasted stroke. All episodic persons were introduced by the author with specific purpose. Thanks to off-stage characters, of which there are many in the comedy, the boundaries of Famusov’s house and the boundaries of time expand.

13. The problem of genre and artistic method .

First of all, let's consider how much the principle of “three unities” is preserved in comedy - the unity of time, the unity of place and the unity of action. The entire action of the play takes place in one house (although in different places his). But at the same time, Famusov’s house in the play is a symbol of the whole of Moscow, Griboyedov’s Moscow, lordly, hospitable, with a leisurely flow of life, with its own customs and traditions. However, the real space of “Woe from Wit” is not limited to Famusov’s Moscow. This space is expanded by the characters of the play themselves, stage and off-stage: Maxim Petrovich, introducing the theme of Catherine’s court; Skalozub, holed up in a trench; a Frenchman “from Bordeaux”, Repetilov with his house “on the Fontanka”; Sophia's uncle, member of the English Club. In addition, the space of comedy is expanded by references to different places in Russia: “He was treated, they say, in sour waters,” “he would have smoked in Tver,” “He was exiled to Kamchatka,” “To the village, to his aunt, to the wilderness, to Saratov.” " The artistic space of the play is also expanded due to the philosophical remarks of the characters: “How wonderfully light was created!”, “No, today the light is not like that”, “Silent people are blissful in the world”, “There are such transformations on earth.” Thus, Famusov’s house symbolically grows in the play into the space of the whole world.

In comedy the principle of the unity of time is preserved. “The entire action of the play takes place over the course of one day, beginning at dawn of one winter day and ending in the morning of the next.<…>It took only one day for Chatsky, who returned to his home, to his beloved girl, to sober up “completely from his blindness, from the vaguest dream.” However, the strict limitation of stage time was psychologically justified in the play. The very essence of the dramatic collision (the clash of Chatsky, with his progressive views, sharp, caustic mind, explosive temperament, with the inert, conservative world of the Famusovs and Repetilovs) demanded this. Thus, observing the classic “unity of time” only formally, Griboyedov achieves maximum concentration stage action. The play takes place over the course of one day, but that day contains a whole life.

A.S. Griboedov only violates the principle of unity of action: there is no fifth act in the comedy, and instead of one conflict, two develop in parallel - love and social. Moreover, if a love conflict has its outcome in the finale, then the social conflict does not receive a resolution within the framework of the content of the play. In addition, we do not observe the “punishment of vice” and the “triumph of virtue” either in the denouement of the love story or in the development of a social conflict.

Let's try to consider the character system of the comedy "Woe from Wit". The classical canon prescribed a strictly defined set of roles: “heroine”, “first lover”, “second lover”, “maid” (heroine’s assistant), “noble father”, “comic old woman”. And the cast of characters rarely exceeded 10–12 people. Griboyedov violates literary tradition, introducing, in addition to the main characters, many secondary and off-stage persons. The main characters formally correspond to the classicist tradition: Sophia is a heroine who has two admirers (Chatsky and Molchalin), Lisa is the best suited for the role of a clever and lively assistant, Famusov is a “noble deceived father.” However, all of Griboedov’s roles seem to be mixed up: Sophia’s chosen one (Molchalin) is far from a positive character, the “second lover” (Chatsky) is an exponent of the author’s ideals, but at the same time an unlucky gentleman. As researchers accurately note, the unusual love triangle is resolved atypically in the play: the “noble deceived father” still does not grasp the essence of what is happening, the truth is not revealed to him, he suspects his daughter of having an affair with Chatsky.

The playwright also violates the principle of unambiguity of characters. So, for example, Famusov appears in the play in a variety of roles: he is an influential government official-bureaucrat, a hospitable Moscow gentleman, an aging red tape worker, a caring father, and a philosopher talking about life. He is hospitable in Russian, responsive in his own way (he took in the son of a deceased friend to raise him). The image of Chatsky is just as ambiguous in comedy. In comedy, he is both a hero and an exposer of social vices, and a bearer of “new trends,” and an ardent lover, doomed to failure, and a secular dandy, and an idealist, looking at the world through the prism of his own ideas. In addition, many romantic motifs are associated with the image of Chatsky: the motif of the confrontation between the hero and the crowd, the motif of unhappy love, the motif of the wanderer. Finally, in comedy there is no clear division of characters into positive and negative. Thus, Griboedov describes the characters in the play in a realistic spirit.

Noting the realistic pathos of the comedy, we note that Griboedov presents us with the life stories of the heroes (from Famusov’s remarks we learn about the childhood of Chatsky, Sophia, and the fate of Molchalin) as a factor determining the development of character.

Another innovative feature of the playwright is the Russian form of names (names, patronymics). Griboedov's predecessors either endowed their characters with surnames borrowed from the proper names of Russian cities, rivers, etc. (Roslavlev, Lensky), or used the first name and patronymic in a comic sense (Matryona Karpovna). In "Woe from Wit" the use of Russian first names and patronymics is already devoid of comedic overtones. However, many surnames in comedy correlate with the motive of rumor, with the words “speak” - “hear.” So, the surname Famusov correlates with Lat. fama, which means "rumor"; Repetilov - from the French. repeater - “repeat”; the names of Molchalin, Skalozub, Tugoukhovsky are demonstratively “speaking”. Thus, Griboedov skillfully uses the classicist principle of “speaking” surnames and at the same time acts as an innovator, introducing the Russian form of first names and patronymics.

Thus, in “Woe from Wit” Griboyedov gives a broad panorama of Russian life in noble Moscow. Life in Griboyedov’s play is shown not in the statistical images of the classic comedy of the 18th century, but in movement, in development, in dynamics, in the struggle of the new with the old.

The love conflict in the plot of the play is intricately intertwined with the social conflict, the characters are deep and multifaceted, typical heroes act in typical circumstances. All this determined the realistic sound of Griboyedov’s comedy.

Comedy “Woe from Wit” by A.S. Griboyedova destroyed traditional genre principles. Sharply different from the classic comedy, the play was not based on love affair. It could not be attributed to the genre of everyday comedy or comedy of characters in its pure form, although the features of these genres were also present in the work. The play was, as contemporaries said, a “high comedy,” the genre that the Decembrists dreamed of appearing. literary circles. Woe from Wit combined social satire and psychological drama; comic scenes were replaced by lofty, pathetic scenes. Let's try to consider genre features plays in more detail.

First of all, let us note the comic elements in the work. It is known that Griboyedov himself called “Woe from Wit” a comedy. And here, of course, it is worth noting the presence in the play of both obvious comic devices and hidden authorial irony. Language comic devices the playwright is hyperbole, alogism, ambiguity, the technique of reduction to absurdity, distortion of foreign words, the use of foreign words in the Russian speech of characters. Thus, we notice hyperbole in the remarks of Molchalin, who strives to please “the janitor’s dog so that it is affectionate.” This technique has something in common with the technique of reduction to absurdity. So, discussing Chatsky’s madness with guests, Famusov notes the “hereditary factor”: “I followed my mother, Anna Aleksevna; The deceased went crazy eight times.” In the speech of old woman Khlestova there is an alogism: “There was a sharp man, he had three hundred souls.” She determines Chatsky’s personal characteristics by his condition. Ambiguity is heard in the speech of Zagoretsky, who condemns the fabulists for “...eternal ridicule of lions! over the eagles! At the end of his speech, he declares: “Whatever you say: Even though they are animals, they are still kings.” It is this line that equates “kings” and “animals” that sounds ambiguous in the play. Comic effect is also created due to the author’s distortion of foreign words (“Yes, the power is not in Madame,” “Yes, from Lankartak mutual teaching”).

“Woe from Wit” is also a comedy of characters. The image of Prince Tugoukhovsky, who, suffering from deafness, misunderstands those around him and misinterprets their remarks, is comedic. An interesting image is of Repetilov, who is both a parody of Chatsky and at the same time the antipode of the main character. There is also a character in the play with a “talking” surname - Skalozub. However, all his jokes are rude and primitive; this is real “army humor”:

I am Prince Gregory and you

I'll give the sergeant major to Voltaire,

He will line you up in three ranks,

Just make a noise and it will instantly calm you down.

Skalozub is not witty, but, on the contrary, stupid. A certain element of the comic is also present in the character of Chatsky, whose “mind and heart are not in harmony.”

The play has features of a sitcom and parody effects. Thus, the author repeatedly plays on two motives: the motive of falling and the motive of deafness. The comic effect in the play is created by Repetilov's fall (he falls at the very entrance, running into Famusov's house from the porch). Chatsky fell several times on the way to Moscow (“More than seven hundred versts flew by - wind, storm; And he was completely confused, and fell how many times ...”). Famusov talks about the fall of Maxim Petrovich at a social event. Molchalin's fall from his horse also causes a violent reaction from those around him. So, Skalozub declares: “Look at how it cracked - in the chest or in the side?” Molchalin’s fall reminds him of the fall of Princess Lasova, who “the other day was completely crushed” and is now “looking for a husband for support.”

The motif of deafness appears already in the first scene of the play. Already in her first appearance, Lisa, having failed to reach Sofya Pavlovna, asks her: “Are you deaf? - Alexey Stepanych! Madam!.. - And fear does not take them!” Famusov covers his ears, not wanting to listen to Chatsky’s “false ideas”, that is, he becomes deaf in at will. At the ball, the countess-grandmother’s “ears got blocked,” and she notes that “deafness is a big vice.” At the ball, Prince Tugoukhovsky is present, who “hears nothing.” Finally, Repetilov covers his ears, unable to bear the choral recitation of the Tugoukhovsky princesses about Chatsky’s madness. The deafness of the characters here contains a deep internal subtext. Famus society is “deaf” to Chatsky’s speeches, does not understand him, does not want to listen. This motive strengthens the contradictions between the main character and the world around him.

It is worth noting the presence of parody situations in the play. Thus, the author parodically reduces the “ideal romance” of Sophia with Molchalin by comparing Liza, remembering Aunt Sophia, from whom the young Frenchman ran away. However, in “Woe from Wit” there is also a different kind of comedy, which ridicules the vulgar aspects of life, exposing the playwright’s contemporary society. And in this regard, we can already talk about satire.

Griboyedov in “Woe from Wit” denounces social vices– bureaucracy, veneration for rank, bribery, serving “persons” rather than “causes,” hatred of education, ignorance, careerism. Through the mouth of Chatsky, the author reminds his contemporaries that there is no social ideal in your own country:

Where? show us, fathers of the fatherland,

Which ones should we take as models?

Aren't these the ones who are rich in robbery?

They found protection from court in friends, in kinship,

Magnificent building chambers,

Where they spill out in feasts and extravagance,

And where foreign clients will not be resurrected

The meanest features of the past life.

Griboyedov's hero criticizes the rigidity of the views of Moscow society, its mental immobility. He also speaks out against serfdom, recalling the landowner who traded his servants for three greyhounds. Behind the lush, beautiful uniforms of the military, Chatsky sees “weakness” and “poverty of reason.” He also does not recognize the “slavish, blind imitation” of everything foreign, manifested in the dominance of the French language. In “Woe from Wit” we find references to Voltaire, the Carbonari, the Jacobins, and we encounter discussions about the problems social order. Thus, Griboyedov’s play touches on all the topical issues of our time, which allows critics to consider the work a “high” political comedy.

And finally, the last aspect in considering this topic. What is the drama of the play? First of all, in spiritual drama Main character. As noted by I.A. Goncharov, Chatsky “had to drink the bitter cup to the bottom - not finding “living sympathy” in anyone, and leaving, taking with him only “a million torments.” Chatsky rushed to Sophia, hoping to find understanding and support from her, hoping that she would reciprocate his feelings. However, what does he find in the heart of the woman he loves? Coldness, causticity. Chatsky is stunned, he is jealous of Sophia, trying to guess his rival. And he cannot believe that his beloved girl chose Molchalin. Sophia is irritated by Chatsky’s barbs, his manners, and behavior.

However, Chatsky does not give up and in the evening he comes to Famusov’s house again. At the ball, Sophia spreads gossip about Chatsky's madness, which is readily picked up by everyone present. Chatsky enters into an altercation with them, makes a hot, pathetic speech, exposing the meanness of his “past life.” At the end of the play, the truth is revealed to Chatsky, he finds out who his rival is and who spread rumors about his madness. In addition, the entire drama of the situation is aggravated by Chatsky’s alienation from the people in whose house he grew up, from the whole society. Returning “from distant wanderings,” he does not find understanding in his homeland.

Dramatic notes are also heard in Griboyedov’s depiction of the image of Sofia Famusova, who suffers her “millions of torments.” She bitterly repents, having discovered the true nature of her chosen one and his real feelings for her.

Thus, Griboyedov’s play “Woe from Wit,” traditionally considered a comedy, represents a certain genre synthesis, organically combining the features of a comedy of characters and sitcoms, features of a political comedy, topical satire, and, finally, psychological drama.

24. The problem of the artistic method of “Woe from Wit” by A.S. Griboedova

The problem of artistic method in Woe from Wit

ARTISTIC METHOD is a system of principles that govern the process of creating works of literature and art.

Written at the beginning XIX century, namely in 1821, Griboedov’s comedy “Woe from Wit” absorbed all the features literary process that time. Literature, like everything else social phenomena, subject to specific historical development. The comedy of A. S. Griboedov was a unique experience in combining all methods (classicism, romanticism and critical realism).

The essence of comedy is the grief of a person, and this grief stems from his mind. It must be said that the problem of “mind” itself was very topical in Griboyedov’s time. The concept of “smart” was then associated with the idea of a person who was not just smart, but “free-thinking.” The ardor of such “clever men” often turned into “madness” in the eyes of reactionaries and ordinary people.

It is Chatsky’s mind in this broad and special understanding that puts him outside the circle of the Famusovs. This is precisely what the development of the conflict between the hero and the environment in comedy is based on. Chatsky's personal drama, his unrequited love for Sophia, is naturally included in the main theme of the comedy. Sophia, for all her spiritual inclinations, still belongs entirely to Famus’s world. She cannot fall in love with Chatsky, who opposes this world with all his mind and soul. She, too, is among the “tormentors” who insulted Chatsky’s fresh mind. That is why the personal and social dramas of the protagonist do not contradict, but complement each other: the conflict of the hero with environment applies to all his everyday relationships, including love ones.

From this we can conclude that the problems of A. S. Griboedov’s comedy are not classicistic, because we do not observe a struggle between duty and feeling; on the contrary, conflicts exist in parallel, one complements the other.

One more non-classical feature can be identified in this work. If from the law of “three unities” the unity of place and time is observed, then the unity of action is not. Indeed, all four actions take place in Moscow, in Famusov’s house. Within one day, Chatsky discovers the deception, and, appearing at dawn, he leaves at dawn. But the plot line is not unilinear. The play has two plots: one is the cold reception of Chatsky by Sophia, the other is the clash between Chatsky and Famusov and Famusov’s society; two storylines, two climaxes and one general denouement. This form of the work showed the innovation of A. S. Griboedov.

But comedy retains some other features of classicism. So, the main character Chatsky is a nobleman, educated. The image of Lisa is interesting. In “Woe from Wit” she behaves too freely for a servant and looks like a heroine classic comedy, lively, resourceful. In addition, the comedy is written predominantly in a low style and this is also Griboyedov’s innovation.

The features of romanticism in the work appeared very interestingly, for the problematics of “Woe from Wit” are partially romantic character. In the center is not only a nobleman, but also a man disillusioned with the power of reason, but Chatsky is unhappy in love, he is fatally lonely. Hence the social conflict with representatives of the Moscow nobility, a tragedy of the mind. The theme of wandering around the world is also characteristic of romanticism: Chatsky, not having time to arrive in Moscow, leaves it at dawn.

In the comedy of A. S. Griboyedov, the beginnings of a new method for that time - critical realism - appear. In particular, two of its three rules are observed. This is sociality and aesthetic materialism.

Griboyedov is true to reality. Knowing how to highlight the most essential things in it, he portrayed his characters in such a way that we see the social laws behind them. Created in “Woe from Wit” extensive gallery realistic artistic types, that is, in comedy typical heroes appear in typical circumstances. The names of the characters in the great comedy have become household names.

But it turns out that Chatsky, an essentially romantic hero, has realistic traits. He's social. It is not conditioned by the environment, but is opposed to it. Man and society in realistic works always inextricably linked.

The language of A. S. Griboyedov’s comedy is also syncretic. Written in a low style, according to the laws of classicism, it absorbed all the charm of the living great Russian language.

Thus, the comedy of Alexander Sergeevich Griboyedov is a complex synthesis of three literary methods, a combination, on the one hand, of their individual features, and on the other, a holistic panorama of Russian life at the beginning of the 19th century.

Griboyedov about Woe from Wit.

25. I. A. Goncharov about the comedy of A.S. Griboyedov "Woe from Wit"

"A MILLION TORNHINGS" (critical study)

I.A. Goncharov wrote about the comedy “Woe from Wit” that it is “a picture of morals, and a gallery of living types, and an ever-burning, sharp satire,” which presents noble Moscow in the 10-20s of the 19th century. According to Goncharov, each of the main characters of the comedy experiences “its own million torments.” Sophia also survives him. Raised by Famusov and Madame Rosier in accordance with the rules of raising Moscow young ladies, Sophia was trained in “dancing, singing, tenderness, and sighs.” Her tastes and ideas about the world around her were formed under the influence of French sentimental novels . She imagines herself as the heroine of a novel, so she has a poor understanding of people. S. rejects the love of the overly sarcastic Chatsky. She does not want to become the wife of the stupid, rude, but rich Skalozub and chooses Molchalin. Molchalin plays the role of a platonic lover in front of S. and can sublimely remain silent until dawn alone with his beloved. S. gives preference to Molchalin because he finds in him many virtues necessary for “a boy-husband, a servant-husband, one of a wife’s pages.” She likes that Molchalin is shy, compliant, and respectful. Meanwhile, S. is smart and resourceful. She gives the right characteristics to those around her. In Skalozub she sees a stupid, narrow-minded soldier who “can never utter a smart word,” who can only talk about “fruits and rows,” “about buttonholes and edgings.” She can’t even imagine herself as the wife of such a man: “I don’t care who he is or who gets into the water.” In her father, Sophia sees a grumpy old man who does not stand on ceremony with his subordinates and servants. And S. evaluates Molchalin’s qualities correctly, but, blinded by love for him, does not want to notice his pretense. Sophia is resourceful like a woman. She skillfully distracts her father’s attention from Molchalin’s presence in the living room in the early hours of the morning. To disguise her fainting and fear after Molchalin's fall from his horse, she finds truthful explanations, declaring that she is very sensitive to the misfortunes of others. Wanting to punish Chatsky for his caustic attitude towards Molchalin, it is Sophia who spreads the rumor about Chatsky’s madness. The romantic, sentimental mask is now torn off from Sophia and the face of an irritated, vindictive Moscow young lady is revealed. But retribution awaits S., too, because her love intoxication has dissipated. She witnessed the betrayal of Molchalin, who spoke insultingly about her and flirted with Lisa. This deals a blow to S.’s pride, and her vengeful nature is revealed again. “I’ll tell my father the whole truth,” she decides with annoyance. This once again proves that her love for Molchalin was not real, but bookish, invented, but this love makes her go through her “millions of torments.” One cannot but agree with Goncharov. Yes, the figure of Chatsky determines the conflict of the comedy, both of its storylines. The play was written in those days (1816-1824), when young people like Chatsky brought new ideas and moods to society. Chatsky’s monologues and remarks, in all his actions, expressed what was most important for future Decembrists: the spirit of freedom, free life, the feeling that “he breathes more freely than anyone else.” Freedom of the individual is the motive of the times and Griboyedov’s comedy. And freedom from dilapidated ideas about love, marriage, honor, service, the meaning of life. Chatsky and his like-minded people strive for “creative, lofty and beautiful arts”, dream of “focusing a mind hungry for knowledge into science”, thirst for “sublime love, before which the world is whole... - dust and vanity.” They would like to see all people free and equal.

Chatsky’s desire is to serve the fatherland, “the cause, not the people.” He hates the whole past, including slavish admiration for everything foreign, servility, sycophancy.

And what does he see around? A lot of people who are looking only for ranks, crosses, “money to live”, not love, but profitable marriage. Their ideal is “moderation and accuracy,” their dream is “to take all the books and burn them.”

So, at the center of the comedy is the conflict between “one sane person” (Griboyedov’s assessment) and the conservative majority.

As always in a dramatic work, the essence of the protagonist’s character is revealed primarily in the plot. Griboyedov, faithful to the truth of life, showed the plight of a young progressive man in this society. Those around him take revenge on Chatsky for the truth, which stings his eyes, for his attempt to disrupt the usual way of life. The girl he loves, turning away from him, hurts the hero the most by spreading gossip about his madness. Here is a paradox: the only sane person is declared insane!

It is surprising that even now it is impossible to read about the suffering of Alexander Andreevich without worry. But such is the power of true art. Of course, Griboyedov, perhaps for the first time in Russian literature, managed to create a truly realistic image of a positive hero. Chatsky is close to us because he is not written as an impeccable, “iron” fighter for truth and goodness, duty and honor - we meet such heroes in the works of classicists. No, he is a man, and nothing human is alien to him. “The mind and heart are not in harmony,” says the hero about himself. The ardor of his nature, which often makes it difficult to preserve peace of mind and composure, the ability to fall in love recklessly, this does not allow him to see the shortcomings of his beloved, to believe in her love for another - these are such natural traits!

Intelligence is a theoretical virtue. For Griboedov's predecessors, only compliance with measures was considered smart. Molchalin, not Chatsky, has such a mind in comedy. Molchalin’s mind serves his owner, helps him, while Chatsky’s mind only harms him, it is akin to madness for those around him, it is he who brings him “a million torments.” Molchalin’s comfortable mind is contrasted with Chatsky’s strange and sublime mind, but this is no longer a struggle between intelligence and stupidity. There are no fools in Griboyedov's comedy; its conflict is built on confrontation different types mind. “Woe from Wit” is a comedy that has transcended classicism.

In Griboedov’s work the question is asked: what is the mind? Almost every hero has his own answer, almost everyone talks about intelligence. Each hero has his own idea of the mind. There is no standard of intelligence in Griboedov's play, so there is no winner in it. “The comedy gives Chatsky only “a million torments” and leaves, apparently, Famusov and his brothers in the same position as they were, without saying anything about the consequences of the struggle” (I. A. Goncharov).

The title of the play contains an extremely important question: what is the mind for Griboyedov. The writer does not answer this question. By calling Chatsky “smart,” Griboyedov turned the concept of intelligence upside down and ridiculed the old understanding of it. Griboyedov showed a man full of educational pathos, but encountering a reluctance to understand it, stemming precisely from the traditional concepts of “prudence”, which in “Woe from Wit” are associated with a certain social and political program. Griboedov's comedy, starting from the title, is addressed not to the Famusovs, but to the Chatskys - funny and lonely (one smart person for 25 fools), striving to change the unchangeable world.

Griboedov created a comedy that was unconventional for its time. He enriched and psychologically rethought the characters and problems traditional for the comedy of classicism; his method is close to realistic, but still does not achieve realism in its entirety. I.A. Goncharov wrote about the comedy “Woe from Wit” that it is “a picture of morals, and a gallery of living types, and an ever-burning, sharp satire,” which presents noble Moscow in the 10-20s of the 19th century. According to Goncharov, each of the main characters of the comedy experiences “its own million torments.

Pushkin's Lyceum Lyrics.

During the Lyceum period, Pushkin appears primarily as the author of lyric poems reflecting his patriotic sentiments in connection with Patriotic War 1812 (“Memoirs in Tsarskoe Selo”), enthusiastically received not only by fellow lyceum students, but even by Derzhavin, who was considered the greatest literary authority of that time. protest against political tyranny ("To Licinius" boldly sketches a broad satirical picture of Russian socio-political reality in the traditional images of Roman antiquity and angrily castigates the "despot's favorite" - the all-powerful temporary worker, behind whom contemporaries discerned the image of the then hated Arakcheev.), rejection of the religious view of the world (“Unbelief”), literary sympathies for the Karamzinists, “Arzamas” (“To a friend the poet,” “Town,” “Shadow of Fonvizin”). The freedom-loving and satirical motifs of Pushkin’s poetry at this time were closely intertwined with epicureanism and anacreoticism.

Nothing from Pushkin’s first lyceum poetic experiments reached us until 1813. But Pushkin’s comrades at the Lyceum remember them.

The earliest Lyceum poems by Pushkin that have come down to us date back to 1813. Pushkin's lyceum lyrics are characterized by exceptional genre diversity. One gets the impression of the young poet’s conscious experiments in mastering almost all the genres already represented in the poetry of that time. This was of exceptional importance in the search own path in lyrics, own lyrical style. At the same time, this genre diversity also determines the features of that stage of Russian poetic development, which was distinguished by a radical breakdown of previous genre traditions and the search for new ones. Pushkin's lyceum lyrics of the first years are distinguished by the predominance of short verse sizes (iambic and trochaic trimeters, iambic and dactyl bimeters, amphibrachic trimeter). This same early period of Pushkin's lyrics is also characterized by a significant length of poems, which is explained, of course, by the poetic immaturity of the young author. As Pushkin's genius develops, his poems become much shorter.

All this taken together testifies, on the one hand, to the period of Pushkin’s conscious apprenticeship in mastering most of the already developed Russian and Western European poetic tradition lyrical forms, and on the other hand, about the inorganicity for Pushkin of almost all poetic templates that came to him from the outside, from which he subsequently and quite soon begins to free himself.

In this initial period of Pushkin’s poetic development, when his whole being was filled with a jubilant feeling of youth and the charm of life with all its gifts and pleasures, the most attractive and, as it seemed to him then, most characteristic of the very nature of his talent, there were traditions of poetic madrigal XVIII culture century, dissolved by the sharp free-thinking of the French Enlightenment.

The young poet was pleased to portray himself as a poet, to whom poetry comes without any difficulty:

The main circle of motives of Pushkin’s lyrics in the first years of the Lyceum (1813-1815) is closed within the framework of the so-called “light poetry”, “anacreontics”, recognized master which Batyushkov was considered. The young poet portrays himself in the image of an epicurean sage, blithely enjoying the light joys of life. Beginning in 1816, elegiac motifs in the spirit of Zhukovsky became predominant in Pushkin’s Lyceum poetry. The poet writes about torment unrequited love, about a prematurely withered soul, grieves about faded youth. There are still many literary conventions and poetic cliches in these early poems by Pushkin. But through the imitative, literary-conventional, the independent, our own is already breaking through: echoes of real life impressions and the authentic inner experiences of the author. “I’m going my own way,” he declares in response to Batyushkov’s advice and instructions. And this “own path” is gradually emerging here and there in the works of Pushkin the Lyceum student. Thus, the poem “Town” (1815) was also written in the manner of Batyushkov’s message “My Penates”. However, unlike their author, who fancifully mixed the ancient and the modern - the ancient Greek “laras” with the domestic “balalaika” - Pushkin gives a sense of the features of life and everyday life of a small provincial town, inspired by real Tsarskoye Selo impressions. The poet was going to give a detailed description of Tsarskoe Selo in a special work specifically dedicated to this, but, apparently, he sketched out only its plan in his lyceum diary (see in volume 7 of this edition: “In the summer I will write “The Picture of Tsarskoe Selo” ).

But already at the Lyceum, Pushkin developed an independent and sometimes very critical attitude towards his literary predecessors and contemporaries. In this sense, “The Shadow of Fonvizin” is of particular interest, in which the poet through the mouth of a “famous Russian merry fellow” and “mocker”, “the creator who copied Prostakova” , makes a bold judgment on literary modernity.

Pushkin continued to write anacreontic and elegiac poems both in these and in subsequent years. But at the same time, the exit in mid-1817 from the “monastery”, as the poet called them, lyceum walls into a big life was also a way out into a larger social theme.

Pushkin begins to create poems that correspond to the thoughts and feelings of the most advanced people Russian society during the period of growing revolutionary sentiments in it, the emergence of the first secret political societies, whose task was to fight against autocracy and serfdom.

The affirmation of the joys of life and love is, to use Belinsky’s term, the main “pathos” of Pushkin’s lyrics of 1815. All this was fully consistent with the ideal of a poet - a singer of light pleasures, which certainly seemed to Pushkin himself at that time to be closest to his character, the purpose of life in general, and the characteristics of his poetic gift.

Elinsky wrote: “Pushkin differs from all the poets who preceded him precisely in that through his works one can follow his gradual development not only as a poet, but at the same time as a person and character. The poems he wrote in one year are already sharply different both in content and form from the poems written in the next” (VII, - 271). In this regard, observations specifically on Pushkin’s Lyceum lyrics are especially revealing.

Pushkin began publishing in 1814, when he was 15 years old. His first printed work was the poem “To a Poet Friend.” There is a different form here than in the earliest poems, and a different genre, but the path is essentially the same: the path of free, easy, spontaneous poetic reflection.

The literary teachers of young Pushkin were not only Voltaire and other famous Frenchmen, but also even more Derzhavin, Zhukovsky, Batyushkov. As Belinsky wrote, “everything that was significant and vital in the poetry of Derzhavin, Zhukovsky and Batyushkov - all of this became part of Pushkin’s poetry, reworked by its original element.” The connection with Zhukovsky during the Lyceum period was especially noticeable in such poems by Pushkin as “The Dreamer” (1815), “The Slain Knight” (1815). Derzhavin also had an undoubted influence on Pushkin. Its influence was evidently manifested in the famous poem of the Lyceum era, “Memories in Tsarskoe Selo.” Pushkin himself recalled his reading of this poem at the exam ceremony in the presence of Derzhavin: “Derzhavin was very old. He was in a uniform and velvet boots. Our exam tired him very much. He sat with his head on his hand. His face was meaningless, his eyes were dull, his lips drooped; his portrait (where he is shown in a cap and robe) is very similar. He dozed off until the exam in Russian literature began. Here he perked up, his eyes sparkled; he was completely transformed. Of course, his poems were read, his poems were analyzed, his poems were constantly praised. He listened with extraordinary liveliness. Finally they called me. I read my “Memoirs in Tsarskoe Selo” while standing two steps from Derzhavin. I am unable to describe the state of my soul; when I reached the verse where I mention Derzhavin’s name, my voice rang like an adolescent, and my heart beat with rapturous delight... I don’t remember how I finished my reading, I don’t remember where I ran away to. Derzhavin was delighted; he demanded me, wanted to hug me... They looked for me but didn't find me.

№19. Topic: A.S. Griboyedov. "Woe from Wit." Content overview. Reading key scenes of the play. Features of the composition.

9th grade literature 10/14/16

Target: - help students remember the features of drama as a type of literature;

Introduce the history of the play;

To help the children feel the atmosphere of the time of action, for this - to find out at what time the comedy takes place;

Introduce students to the characters of the comedy, give a general idea of their characters;

During the classes :

Org moment.

Teacher's word

Hello guys! In the last lesson we talked about the personality of Alexander Sergeevich Griboyedov, his extraordinary talents and outstanding abilities, about the fate of this man. The apogee of G’s literary activity was the play in verse “Woe from Wit.” Today we will get acquainted with this work and its characters, we will read act 1.

Repetition of theoretical and literary concepts.

First, let's remember the features of drama as a type of literature. Let's do a reverse dictation - I read the definitions of terms related to drama, and you write down the terms themselves in your notebook.

form oral speech, a conversation between two or more persons – dialogue

one of the main types of drama, in which the conflict, action and characters are interpreted in the forms of the funny and imbued with the comic - comedy

explanations with which the playwright precedes or accompanies the course of action in the play - remark

statements of the characters, from the cat's dialogue in dramatic or narrative work – replica

one of the types of drama, which is based on a particularly intense, irreconcilable conflict, often ending in the death of the hero - tragedy

in a literary work, the speech of a character addressed to himself or others, independent of the remarks of other characters – monologue

one of the completed parts into which a play or performance is divided - act\action

So, now let's remember the definition of drama.

Drama is one of the main types of literature, along with epic and lyric poetry, intended for production on stage.

History of creation

Griboedov became the creator of one of the greatest dramas of all time.Listen to how he went about writing his great work .

In 1818, G was offered to go to diplomatic service in Persia, and he had to accept this appointment. In August 1818, he left through Moscow for the Caucasus, from where he was supposed to move on.

V M visited relatives. His mother was pleased with his service and did not take him seriously literary studies. Then G wrote to his friend Stepan Nikitich Begichev:“Everything about M is not for me. Idleness, luxury, not associated with the slightest feeling for anything good.”

In 1819 he managed to get to Tiflis, where he greedily pounced on Russian magazines and visited society. He wanted to write, he compared the Persian order with the Russian one, and gov, what“The officials here and there are disgusting” . It is known thatin 1820 G already had the idea of “Woe from Wit” in his head, and the first handwritten text of the play that has survived to this day is dated 1821. Communicating withdisgraced (disliked by the authorities) officers in the Caucasus, G learns about army drill, the persecution of education, the cruelty of censorship, all this affects the concept of the play.

In the spring of 1824 went to the capital, hoping to publish a comedy or stage it in a theater.He finished the play already in M at the Demut Hotel on the Moika. In June he writes to B:“I read it to Krylov, Zhandre, Shakhovsky... There is no end to the thunder, the noise, the admiration, the curiosity.”

But the author’s hopes did not come true: neither literary nor theatrical censorship allowed the comedy to pass. Then friends began to distribute it on lists - they rewrote the comedy by hand and distributed it among loved ones, relatives, and friends.

Completed in 1824 and published during G’s lifetime only in fragments, the play was not allowed on stage by censors for a long time. In 1829, after G.’s death, some acts of the play were staged on stage; in 1831, heavily corrected by censorship, the comedy was staged in full . Subsequently, to this day, “Woe from Wit” is staged in the most different theaters, in various interpretations; Views of the play change in accordance with time and values, but the work itself never ceases to be included in the list of the greatest dramas of Russian literature.

Let's touch this greatness, let's try to compose own opinion about the play and its characters.

Students' message about the Features of the composition of the play .

Reading the poster.

Let's turn our attention to the characters in the comedy.

We open the poster. You can see that there are many characters, but G did a masterful job on each of them. Therefore, some features of the character can already be read in the names and surnames of the heroes.What are these first and last names called? (speaking)

So, let's go in order.

Pavel Afanasyevich Famusov, manager at the government office – lat.fama- “rumor” or English.Famous- “famous”. A civil servant occupying a fairly high position.

Sofya Pavlovna, his daughter – Sophia is often called positive heroines, wisdom. (“Minor” by Fonvizin)

Alexey Stepanovich Molchalin, Famusov’s secretary, living in his house - silent, “the enemy of insolence”, “on tiptoe and not rich in words”, “will reach the known degrees - after all, nowadays they love the dumb.”

Colonel Skalozub, Sergei Sergeevich – often reacts inadequately to the words of the heroes, “cliffs”.

Natalya Dmitrievna, a young lady, Platon Mikhailovich, her husband, Gorichi - a woman is not in the first place (!), PM is a friend and like-minded person, but a slave, is under pressure from his wife and society - “grief”.

Prince Tugoukhovsky and Princess, his wife, with six daughters . – again, many women are actually hard of hearing, the motive is deafness.

Khryumins. – the name speaks for itself – a parallel with pigs.

Repetilov . – Latin, repeats after interlocutors.

Alexander Andreevich Chatsky – originally Chadian (in Chad, Chaadaev); an ambiguous multifaceted personality whose character cannot be expressed

1. Exposition, plot, climax, denouement of the comedy.

“Strange as it may seem, telling the plot of the play is not as easy as it might seem at first glance. And what's even stranger is that it's even harder to tell full content a play that has already become famous and included in the anthology.” This sincere confession about “Woe from Wit” belongs to one of the best experts on comedy - Vl. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko. “Telling the plot” of “Woe from Wit” means, first of all, exposing the skeleton of the play, revealing its internal plan, defining the script, and finally revealing the dynamics of the dramatic movement. This, indeed, is not so easy, not because the script is too complicated or confusing: “Woe from Wit” was created in a beautiful way noble simplicity and easy elegance of style. But the psychological motivation for the actions of the characters in the play is closely intertwined with the logical tasks of the stage plan, and “telling the plot” in full would mean recreating the entire psychological content of a dramatic work, which is almost as difficult as telling the content of a musical work or a painting.

In correspondence with Griboedov, an expert in dramatic literature, P.A. Katenin wrote to the poet: the main error in the plan is “the scenes are connected arbitrarily.” The famous vaudevillian A.I. was the first to speak out on the same issue in the press. Pisarev, who published a meticulous article under the pseudonym Pilada Belugina in “Bulletin of Europe” (1825) in which he stated: “You can throw out each of the faces, replace them with others, double their number - and the course of the play will remain the same. Not a single scene follows from the previous one or is connected with the subsequent one. Change the order of the events, rearrange their numbers, throw out any, insert whatever you want, and the comedy will not change. There is no need in the whole play, it has become, there is no plot, and therefore there can be no action.” Later, Prince P.A. Vyazemsky, who in Sovremennik (1837) wrote: “There is no action in the drama, as in the works of Fonvizin, or even less (!).”

The best ancient interpreter of the “Woe from Wit” script, Goncharov, inspires the reader with the idea that everything in the play is fused inseparably, organically.

“Every step of Chatsky, almost every word in the play is closely connected with the play of his feelings for Sophia, irritated by some kind of lie in her actions, which he struggles to unravel until the very end”; “He came to Moscow and to Famusov, obviously for Sophia and to Sophia alone. He doesn’t care about anyone else.” This is the stimulus that drives the play.

Sophia, “not stupid herself, prefers a fool (i.e. Molchalin) to an intelligent person,” and this is the second lever of intrigue. These two factors, with all their “necessity,” determine a long series of moments in the stage struggle: Sophia’s dream, her fainting, her struggle with Chatsky over Molchalin, up to and including the evil gossip, Chatsky’s misunderstanding of Sophia and his role in the love affair and the final break with his beloved girl . This also explains the long series of actions in the stage movement: the clashes between Chatsky and Famusov in the second act, his behavior at the ball, the “voice of general hostility,” the success of gossip about madness and its echoes in the traveling of the guests in the fourth act.

Thus, “Necessity,” the internal compulsion in the development of the play, is established undeniably, the “plot” of the play is also revealed, the moments and elements of the “action” are established.

Each action is divided into two relatively independent paintings, and in both halves of the play there are “love” pictures at the “edges”, and “social” ones in the center.

Objecting to the reproaches of some critics that Griboedov’s comedy supposedly lacks action and plot, V.K. Kuchelbecker writes in his diary: “... it would not be difficult to prove that in this comedy there is much more action or movement than in most of those comedies, the entire entertainment of which is based on the plot. In “Woe from Wit,” exactly, the whole plot consists of Chatsky’s contrast to other persons... Dan Chatsky, other characters are given, they are brought together, and it is shown what the meeting of these antipodes must certainly be like - and that’s all. It’s very simple, but in this very simplicity lies the news, the courage, the greatness of that poetic imagination, which neither Griboyedov’s opponents nor his awkward defenders understood.”

“Even at the end of the 19th century, one could come across the statement that in the play there is no intriguing movement from the beginning, springily leading to the denouement,” “that if we are talking about events that determine the entertainment of the play, then there are no such events in the play.” But isn’t there a plot point in the appearance of the lover Chatsky at the moment when Molchalin has just left Sophia and the reader begins to anxiously and impatiently watch who will go next and how this unexpected coincidence and acute conflict will end. “However, from time to time, in certain scenes an illusion of tension arises, for example in the scene of Molchalin’s fall.” Why illusion? This is one of the links in a whole chain of tense episodes, which necessarily lead to a tense denouement after the climax of the play in the scene of Chatsky’s clash with the entire society and the spread of gossip about his madness. The reader awaits how it all ends.

At the same time, “Woe from Wit” is in no way one of those plays whose course of action and outcome can be predicted in advance. Griboyedov himself treated such drama with disdain. “When I guess the tenth scene from the first scene, I gape and run out of the theater,” he wrote. Right up to Famusov’s final phrase, “Woe from Wit” is perceived with ever-increasing attention and tension.

The ending of the comedy is unusual, combining Chatsky’s break with Sophia and at the same time Chatsky’s break with Famus society, a challenge to it.

2. Characteristics of the development of the action of the comedy.

The social theme - the clash between Chatsky and Famusov's Moscow - is outlined in the first act, intensifies in the second, reaches a climax in the third and receives its final conclusion in the fourth act. A love affair also goes through the same stages of development; Moreover, its “center of gravity” lies in the first two acts of the play - they are oversaturated with doubts that intrigue each of the characters: “Which of the two?” (for Famusov this is either Molchalin or Chatsky; for Chatsky - Molchalin or Skalozub; it is possible that for Skalozub the same question exists as for Famusov; a comic triangle is built right there, introducing additional funny misunderstandings. yu Famusov - Liza-Molchalin ; however, as it turns out at the end of the second act, here too the two unlucky rivals are confronted by a third - Petrusha).

3. Two leading plot collisions of the comedy.

Goncharov provided a huge service in understanding the play. It was he who explained once and for all that dramatic movement follows two intertwining lines: love intrigue and social drama...

The basic principle general plan Griboyedov's plays are the law of artistic symmetry.

The comedy has four acts, and first of all it is divided into two halves, which are in a dialectical relationship with each other. In the first half, a comedy based on a love affair predominates (and therefore the first two acts are “sparsely populated”), in the second - a social comedy, but both comedies are not isolated, but are closely intertwined.

Two comedies seem to be nested within one another: one, so to speak, is private, petty, domestic, between Chatsky and Sophia, Molchalin and Liza; This is the intrigue of love, the everyday motive of all comedies. When the first is interrupted, another unexpectedly appears in the interval, and the action begins again, a private comedy plays out into a general battle and is tied into one knot.

The hero of the play is in love with a girl, “for whom he came to Moscow alone,” and “the girl, not stupid herself, prefers a fool smart person" “Every step of Chatsky, almost every word in the play is closely connected with the play of his feelings for Sophia, irritated by some kind of lie in her actions, which he struggles to unravel until the very end”; “He came to Moscow and to Famusov, obviously for Sophia and to Sophia alone. He doesn’t care about anyone else.” This is the stimulus that drives the play.

The “intrigue of love” merges into one organic whole. Is there another struggle connected with it – a social one? Griboyedov himself pointed out this connection in the character of the hero and the society surrounding him: ... in my comedy there are 25 fools for one sane person, and this person, of course, is contrary to the society around him, no one understands him, no one wants to forgive him, why is he a little above others."

The question may be to what extent both elements of the stage struggle, love and social, are balanced, whether one of them outweighs and to what extent.

Having outlined the character of the two main representatives of the old and new generations in the first act, the author brings them together in the second act - he makes Chatsky a witness to Famusov’s conversation with Skalozub and renews his hatred of Moscow society in his soul, developing it gradually along with jealousy. And Chatsky’s love, jealousy, suspicions - all this permeates the depiction of the morals of society - two ideas, one not contradicting the other, intertwine with one another and develop one another.

4. Originality of the composition. The leading compositional principle of comedy.

While examining the composition “Woe from Wit,” N.K. made the correct observation. Piksanov, however, interpreted it locally and therefore inaccurately: “Regarding the architectonics of the third act, it is worthy of attention<…>one feature. This act is easily divided into two actions, or pictures. One part is formed by the first three phenomena. They are separated from the steel text not only by the special large remark “Evening. All the doors are wide open - etc.”, but also in meaning: the first part is integral as Chatsky’s attempt to communicate with Sophia, the second gives a picture of the ball. If the third act were divided into two, the result would be a classic five-act comedy.”

However, the division of the third act into two “pictures” is neither an exception nor a rudiment of the classical architectonics of drama in Griboedva’s comedy.

5. System of images. Basic principles of “alignment of forces”.

The comedy depicts features of life and human relationships that went far beyond the early 19th century. Chatsky became a symbol of nobility and love of freedom for the next generation. Silence, Famusism, Skalozubovism have become common names to denote everything low and vulgar, bureaucracy, rude soldiery, etc.

The whole play seems to be a circle of faces familiar to the reader, and, moreover, as definite and closed as a deck of cards. The faces of Famusov, Molchalin, Skalozub and others were etched into the memory as firmly as kings, jacks and queens in cards, and everyone had a more or less consistent opinion about all the faces, except for one - Chatsky. So they are all drawn correctly and strictly, and so they have become familiar to everyone. Only about Chatsky many are perplexed: what is he? It's like he's some kind of fifty-third mysterious map in the deck.

One of the most striking, powerful and imaginative confrontations in world poetry is that which Griboyedov captured with the characters Chatsky-Molchalin. The names of these characters are inevitably household names and as such belong to all of humanity. “The role and physiognomy of Chatsky is unchanged...” Chatsky is inevitable with every change of one century to another... Every business that requires renewal evokes the shadow of Chatsky... an exposer of lies and everything that has become obsolete, that drowns out new life, “free life.”

6. Speech characteristics of the main characters, the connection of this aspect of the work with the system of images.

In the language of comedy, we encounter phenomena that characterize not all of Griboyedov’s Moscow, but individual characters in the comedy.

Episodic persons cannot claim a special characteristic language, but larger characters, especially the main ones, each speak their own characteristic language.

Skalozub’s speech is lapidary and categorical, avoids complex constructions, and consists of short phrases and fragmentary words. Skalozub has the whole service on his mind, his speech is sprinkled with specially military words and phrases: “distance”, “irritation”, “sergeant major in Voltaire”. Skalozub is decisive, rude: “he’s a pitiful rider,” “make a sound, it’ll instantly calm you down.”

Molchalin avoids rude or common expressions; he is also taciturn, but for completely different reasons: he does not dare to pronounce his judgment; he equips his speech with respectful With: “I-s”, “with papers-s”, “still-s”, “no-s”; chooses delicate cutesy expressions and turns: “I had the pleasure of reading this.” But when he is alone with Lisa and can shed his conventional mask, his speech gains freedom, he becomes rude: “my little angel,” “we’ll waste time without a wedding.”

Zagoretsky's speeches are brief, but also unique in manner. He speaks briefly, but not as weightily as Skalozub, and not as respectfully as Molchalin, he speaks quickly, swiftly, “with fervor”: “Which Chatsky is here? “A well-known family,” “you can’t reason with her,” “No, sir, forty barrels.”

Khlestova’s style of speech seems to be the most consistent, most colorful language. Everything here is characteristic, everything is deeply truthful, the word here is the thinnest veil, reflecting all lines of thought and emotion. This is the style of speeches of a great Moscow lady, intelligent and experienced, but primitive in culture, bad, as in dark forest, knowledgeable about “boarding houses, schools, lyceums,” perhaps even semi-literate, a mother-commander in rich lordly living rooms, but close in all respects to the Russian village. “Tea, I cheated at cards,” “Moscow, you see, is to blame.” Not only Molchalin or Repetilov, but also others, older than them, Khlestova, of course, says “you”, her speech is unceremonious, rude, but apt, full of echoes of the people’s element.

Famusov with Molchalin, Liza, and his daughter is unceremonious and does not mince words; with Filka he is simply lordly rude; in disputes with Chatsky, his speech is full of rapid, heated phrases reflecting a lively temperament; in a conversation with Skalozub, she is flattering, diplomatic, even calculatedly sentimental. Famusov is entrusted with some resonating responsibilities, and in such cases he begins to speak in a foreign language - like Chatsky: “the eternal French, where fashion comes from for us, both authors and muses, destroyers of pockets and hearts. When the Creator will deliver us,” etc. Here the features of an artificial construction of a phrase and the same choice of words appear.

The speech of Chatsky and Sophia is far from the type of speech of the other characters. It depends on the content of the speeches. They must express the complex range of feelings experienced by the heroes of stage wrestling and alien to others: love, jealousy, mental pain, vindictiveness, irony, sarcasm, etc. In Chatsky’s monologues there is a great element of accusatory, social motives, in Sophia’s speeches there is more personal, intimate.

In the style of speeches of Sophia and Chatsky, we encounter many differences from the language of the other characters. It has its own special vocabulary: participation, crookedness, barbs, ardor, alien power; its own system of epithets: demanding, capricious, inimitable, majestic; its own syntax - with developed sentence forms, simple and complex, with a tendency towards periodic construction. Here, there is no doubt the artist’s desire to highlight the characters not only in imagery or ideology, but also in language.

Chatsky’s speech is very diverse and rich in shades. “Chatsky is an artist of words,” V. Fillipov rightly notes. “His speech is colorful and varied, picturesque and figurative, musical and poetic, he masterfully speaks his native language.”

Chatsky’s remarks and monologues capture the emotional and lexical features of the language of the advanced intelligentsia of the 20s. last century.

Chatsky acts in the age of romanticism, and his romantic sensitivity and fiery passion are reflected in his lyrical-romantic phraseology, either expressing passionate hope for Sophia’s love, or complete sadness and melancholy.

Chatsky’s sad reflections could become a romantic elegy (“Well, the day has passed, and with it All the ghosts, all the smoke and smoke of Hope that filled my soul”).

The language and syntax of these poems are close to the elegy of the 20s.

But Chatsky not only loves, he denounces, and his lyrical speech is often replaced by the speech of a satirist, an epigramist, castigating the vices of Famus society in two or three words, accurately and expressively branding its representatives. Chatsky loves aphorisms, which reflect his philosophical mindset and his connections with the Enlightenment. His language is deeply characterized by elements that go back to solemn and pathetic speech. goodies classicist drama, which was widely used in the plays and civil poetry of the Decembrists. Chatsky does not avoid Slavicisms, which was closely connected with the Decembrists’ sympathy for the ancient Russian language of the Slavic patriot. Filled with public pathos, Chatsky’s speeches in their structure and “high style” undoubtedly go back to the political ode of Radishchev and the Decembrist poets. Along with this, Griboyedov’s hero has a good sense of his native language, its spirit, its originality. This is evidenced by the idioms he uses: “She doesn’t give a damn about him,” “that’s a lot of nonsense,” and others. Human high culture, Chatsky rarely resorts to foreign words, raising this to a consciously pursued principle, so that “our smart, vigorous people, even in language, do not consider us to be Germans.”

There are two styles of speech in the play, lyrical and satirical, to accomplish two tasks: firstly, to convey all the vicissitudes of an intimate love drama, and secondly, to characterize, evaluate, and expose Famusism, Skalozubovism, and all of old Moscow.

Individualization of characters was facilitated speech characteristics. Indicative in this regard is Skalozub’s speech with its military terms, phrases similar to military orders, rude expressions of Arakcheev’s military, like: “you can’t faint with learning,” “teach in our way - once, twice,” and so on. Molchalin is delicate, insinuating, and taciturn, loving respectful words. The speech of Khlestova, an intelligent, experienced Moscow lady, unceremonious and rude, is colorful and characteristic.

7. Stylistic diversity of comedy language. Indicate the signs of “colloquial” language.

The play has become an endless arsenal of figurative journalistic means. First of all, it is necessary to note Griboyedov’s linguistic skill. Pushkin, who was quite critical of the play based on his first impression, immediately made a reservation, however: “I’m not talking about the poems, half of them should become proverbs.” And so it happened. Suffice it to say that in “ Explanatory dictionary living Great Russian language” by Vladimir Dahl, where more than thirty thousand proverbs are given as examples - several dozen of them go back to “Woe from Wit”, but Dahl used exclusively field notes. In this respect, only I.A. competes with Griboyedov. Krylov, but he left us over two hundred fables, while Griboyedov’s sayings were adopted by the language from one of his works.

Griboedov included salt, epigram, satire, and colloquial verse in the speech of his heroes. It is impossible to imagine that another speech taken from life could ever appear. Prose and verse merged here into something inseparable, then, it seems, so that it would be easier to retain them in memory and put into circulation again all the intelligence, humor, jokes and anger of the Russian mind and language collected by the author.

Griboyedov’s contemporaries were struck, first of all, by the “liveliness of the spoken language,” “exactly the same as they speak in our societies.” Indeed, the number of words and turns of phrase in live, colloquial speech is enormous in “Woe from Wit.” Among them, a noticeable group consists of the so-called idiocy, which gives the language of the play a special charm and brightness. “Out of the yard”, “get away with it”, “without a soul”, “a dream in your hand” - these are examples of such expressions. Numerous cases of peculiar semantics are interesting: “announce” = tell, “bury” = hide, “news” = news, anecdote.

Close to this is the group of words and expressions that the first critics of “Woe from Wit” defined as “Russian flavor” - elements of the folk language: “maybe”, “vish”, “frightened”, “if”.

Then there is a group of words of living speech, incorrect from a formal-grammatical or literary-book point of view, but constantly used in society and people: “It’s a pity”, “Stepanoch”, “Mikhaloch”, “Sergeich”, “Lizaveta”, “uzhli” . There are features characteristic of old Moscow living speech: “prince-Gregory”, “prince-Peter”, “prince Peter Ilyich”, “debtor” = creditor, “farmazon”, “dancer” = ballerina.

All these features give the language of “Woe from Wit” a unique flavor and form in it a whole element of speech - lively, colloquial, characteristic.

Griboyedov widely and abundantly used live action in his comedy. colloquial speech. In general, the speech of Famusov's society is extremely characteristic for its typicality, its color, a mixture of French and Nizhny Novgorod. The features of this jargon can be clearly illustrated by the language of Famus society. In his comedy, Griboedov subtly and evilly ridicules the fact that the majority of Frenchized representatives of the nobility do not know how to speak their native word, their native speech.

The author of “Woe from Wit” sought, on the one hand, to overcome smooth writing, the impersonal secular language with which lungs were written love comedies Khmelnitsky and other young playwrights. At the same time, he persistently cleared his works of ponderous, archaic book speech that goes back to the “high style.”

Griboedov's main artistic goal was to enrich literary language practice of live conversational speech.