Comparative mythology. Comparative mythology and its method

Serf Russia in the second half of the 18th century

In the 2nd half of the 18th century. Russia expanded its borders in the south and west, annexing the Black Sea and Azov regions, the Buzh-Dniester lands, Belarus, and part of the Baltic territory.

Compared to the first half of the 18th century. By the end of the century, the population doubled and amounted to 36 million people, with only 4% of the population living in cities; in Russia the predominant population was rural. Up to half the population are privately owned peasants.

The development of the annexed territories was accompanied by the growth of feudal-serf relations in breadth and depth.

For 1783–1796 serfdom spread to the Ukrainian lands, Crimea and Ciscarpathia. Agriculture developed mainly extensively, due to new Russian lands and advancement into suitable areas of the Urals and Siberia.

With the increasing exploitation of peasants, serfdom expanded deeper. By a decree of 1765, landowners were allowed to exile their peasants without trial or investigation to hard labor in Siberia, which was counted as fulfilling conscription duties. The sale of peasants and cruel punishments were widespread. According to the decree of 1763, peasants themselves paid the costs, if they were recognized as instigators, for suppressing unrest. Finally, in 1767, Catherine II issued a decree prohibiting peasants from complaining about their masters.

In the 2nd half of the 18th century, two large regions with different forms of serf exploitation were identified in Russia. In the black earth provinces with fertile soil and in the south, corvée prevailed. Sometimes the landowner took the land from the peasant, and he actually turned into a farm laborer working for meager pay. In areas with infertile soil, cash rent prevailed. Some landowners sought to increase the profitability of their estates, used technical devices, introduced crop rotation, introduced new crops imported from other countries - tobacco, potatoes, sunflowers, built manufactories, then using the labor of their serfs. All these innovations were a sign of the beginning of the disintegration of serfdom.

In 1785, a special “craft regulation” (from the “Charter of Grant to Cities”) regulated the development of crafts in cities. Craftsmen were grouped into workshops, which elected foremen. This organization of life for artisans created better conditions for their work and apprenticeship. With this provision, the government hoped to turn urban artisans into one of the classes of feudal society.

Along with the city, crafts were widely developed in industrial villages. Thus, Ivanovo was famous for textile production, Pavlovo for metal products, Khokhloma for woodworking, Gzhel for ceramics, etc.

Second half of the 18th century. for Russia this means further growth in manufacturing production. If in the middle of the century there were more than 600 manufactories, then at the beginning of the 19th century. up to 1200. Manufactories using the labor of serfs predominated. But manufactories using free labor also appeared, in particular in textile production. The role of civilians was played by serfs released on quitrent. The relations of free employment were capitalist relations.

In 1762, it was forbidden to purchase serfs for factories, and manufactories founded after this year used civilian labor.

In 1775, peasant industry was allowed, which led to an increase in the number of business owners from merchants and peasants.

The process of the formation of capitalist relations became more and more noticeable and irreversible. The market for civilian labor appeared and began to grow. However, new relations appeared in a country where serfdom dominated, which influenced this process.

In the 2nd half of the 18th century. The all-Russian market continued to form. The specialization of the regions became more noticeable: the black earth Center and Ukraine produced bread, the Volga region supplied fish, leather, wool, the Urals - iron, Novgorod and the Smolensk lands - flax and hemp, the North - fish, furs, Siberia - furs, etc. All this was exchanged at auctions and fairs, the number of which grew. Through the ports of the Baltic and Black Sea regions, Russia conducted active foreign trade, exporting its goods - metal, flax, hemp, sailing cloth, timber, leather, bread. Russia imported sugar, cloth, silk, coffee, wine, fruit, tea, etc. Russia's leading trading partner at that time was England.

Trade primarily served the needs of the state and the ruling class. But it contributed to the establishment of a capitalist structure in the country.

In the 2nd half of the 18th century. The class system of the country is strengthened. Each category of the population - nobility, clergy, peasantry, townspeople, etc. - received rights and privileges by appropriate laws and decrees.

In 1785, in development of the Manifesto on the Freedom of the Nobility (1762), a Charter to the Nobility was issued, which confirmed the exclusive right of landowners to own land and peasants. The nobles were freed from compulsory service and personal taxes, and received the right to special representation in the district and province in the person of leaders of the nobility, which increased their role and importance locally.

Strengthening the class system in the 18th century. was an attempt to maintain the power of the ruling class, to preserve the feudal system, especially since this happened on the eve of the Great French Revolution.

Thus, in the 2nd half of the 18th century. The reserves of feudalism in the country had not yet been exhausted, and it could still ensure progress, despite the development of capitalist relations.

Catherine II. Enlightened absolutism 60–80 XVIIIV. Catherine II (1762 - 1796), having taken the throne in difficult times, showed remarkable abilities as a statesman. And indeed, her inheritance was not easy: the treasury was practically empty, the army had not received money for a long time, and manifestations of the ever-growing protest of the peasants posed a great danger to the ruling class.

Catherine II had to develop a policy that would meet the needs of the time. This policy was called enlightened absolutism. Catherine II decided to rely in her activities on certain provisions of the ideologists of the Enlightenment - the famous philosophical movement of the 18th century, which became the ideological basis of the Great French bourgeois revolution (1789–1794). Naturally, Catherine II set out to use only those ideas that could help strengthen serfdom and feudal orders in the country.

In Russia, apart from the nobility, there were no other forces capable of personifying social progress.

The French encyclopedists Voltaire, Diderot, Montesquieu, and Rousseau developed the main provisions of the Enlightenment, affecting the problems of social development. At the center of their thinking was the theory of “natural law,” according to which all people were naturally free and equal. But human society in its development it deviated from the natural laws of life and came to an unjust state, oppression and slavery. In order to return to fair laws, it was necessary to enlighten the people, the encyclopedists believed. An enlightened society will restore fair laws, and then freedom, equality and fraternity will be the main meaning of the existence of society.

Philosophers entrusted the implementation of this goal to enlightened monarchs who wisely used their power.

These and other ideas were adopted by the monarchs of Prussia, Austria, and Russia, but approached them from the position of serfdom, linking the demands of equality and freedom with the strengthening of the privileges of the ruling class.

Such a policy could not be long-term. After the Peasants' War (1773 - 1775), as well as in connection with the revolution in France, the end of enlightened absolutism came, the course towards strengthening internal and external reaction became too obvious.

Catherine II had been corresponding with Voltaire and his associates since 1763, discussing with them the problems of Russian life and creating the illusion of interest in applying their ideas.

In an effort to calm the country and strengthen her position on the throne, Catherine II in 1767 created a special commission in Moscow to draw up a new set of laws Russian Empire to replace the "Conciliar Regulations" of 1649

573 deputies were involved in the work of the Commission - from nobles, various institutions, townspeople, state peasants, and Cossacks. Serfs did not participate in this Commission.

The commission collected orders from localities to determine people's needs. The work of the Commission was structured in accordance with the “Order” prepared by Catherine II - a kind of theoretical justification for the policy of enlightened absolutism. The order was voluminous, containing 22 chapters with 655 articles, most of the text was a quotation book from the works of enlighteners with justification for the need for strong monarchical power, serfdom, and the class division of society in Russia.

Having begun its meetings in the summer of 1767, the Commission solemnly awarded Catherine II the title of “great, wise mother of the Fatherland,” thereby declaring her recognition by the Russian nobility. But then, unexpectedly, the peasant question came into focus. Some deputies criticized the system of serfdom; there were proposals to attach the peasants to a special board, which would pay the landowners' salaries from peasant taxes; this was a hint of the desire to free the peasants from the power of the landowners. A number of deputies demanded that peasant duties be clearly defined.

The commission worked for more than a year and was dissolved under the pretext of the outbreak of war with Turkey, without creating a new code.

Catherine II learned from parliamentary speeches about the mood in society and in further legislative practice proceeded from her “Order” and the materials of this Commission.

The work of the Statutory Commission showed a growing critical, anti-serfdom attitude in Russian society. Pursuing the goal of influencing public opinion, Catherine II took up journalism and began publishing in 1769 the satirical magazine “All Things”, in which, trying to divert attention from criticism of serfdom, she offered criticism of human weaknesses, vices, and superstitions in general.

The Russian enlightener N.I. spoke from a different position. Novikov. In the magazines “Drone” and “Painter” he published, he spoke out, defending specific criticism of vices, namely, he castigated the unlimited arbitrariness of the landowners and the lack of rights of the peasants. It was expensive for N.I. Novikov had this position, he had to spend more than 4 years in the Shlisselburg fortress,

Criticism of serfdom and Novikov’s social activities contributed to the formation of anti-serfdom ideology in Russia.

A.N. is considered to be the first Russian revolutionary-republican. Radishchev (1749 – 1802). His views were formed under the strong influence of internal and external circumstances. These are the Peasant War of E. Pugachev, and the ideas of French and Russian enlighteners, and the revolution in France, and the War of Independence in North America (1775 - 1783), and the work of Novikov, and the statements of deputies of the Statutory Commission.

In the work "Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow", the ode "Liberty" and others, Radishchev called for the abolition of slavery and the transfer of land to the peasants, for the revolutionary overthrow of the autocracy.

Catherine II called Radishchev “a rebel worse than Pugachev.” He was arrested and sentenced to death, commuted to 10 years of exile in Siberia (Ilimsky prison).

So, Catherine II is a traditional figure, despite her negative attitude towards the Russian past, despite the fact that she introduced new techniques in management, new ideas into social circulation. The duality of the traditions that she followed also determines the dual attitude of her descendants towards her. The historical significance of Catherine's era is extremely great precisely because in this era the results of previous history were summed up and the historical processes that developed earlier were completed.

Encyclopedia Signs and Symbols

There is such a science - comparative mythology. She demonstrates miracles. If we compare the endless variety of cosmologies, cultures, gods with each other, we will discover numerous correspondences and parallels. From the night of human prehistory the most bizarre associations emerge. In the most opposite parts of the globe, images, systems, rituals, dances and personalities are found that are so similar to each other that it would be absurd to attribute all this to the whim of chance. Comparative religion is gaining incredible popularity, accompanied by both strictly scientific evidence and sometimes very amateurish “Sherlock Holmesism.” Millions of readers are intensely comparing evidence and evidence that confirms or refutes the similarity of gods and myths and their common origin. The most famous in this tinsel of discoveries were the aliens from space Dsniksna. Despite all the scientific controversy of his postulates, it must be admitted that Dsniken aroused public interest in eternal question: where do we come from, what is the original matrix with which a person is printed, his behavior, his emotions, his thinking?

In Germany, the foundations of the comparative scientific study of religions were laid after scientific world got acquainted with “Rigvsda” - one of the most ancient monuments of philosophy and mythology of India. The Indian pantheon is so densely populated, there are so many gods represented, its myths are so colorful and varied in plot that it is not difficult to find parallels in Indian mythology. Even Celtic and Greek mythologies cannot deny kinship with Indian roots. It is enough to name the name Prometheus and remember that the Indian “pramata” means “to take for oneself”, as well as “to receive fire by friction.”

The trident of Shiva is again found in the hands of Poseidon and the Celtic sea god Mannanan, son of Lehr, but Christian devils in hell are also brandishing tridents. The healing god Apollo-Aesculapius reveals a striking similarity with the Indian Rudra: here is initiation into youth, and arrows that bring illness, and the art of healing. There is a legend in India in which God, the lord of the winds, fought with demons who stole his cattle. How can one not recall the Greek Apollo, who was looking for the cows stolen from him? The battle of Hercules with Geryon finds a parallel in the battle of Indra with Vitra. When the ancient Germans told of the wild hunter and mad boars, when the classical Greek myths tell of the orgies of Dionysus, we also remember Indra, who rides on a white horse with the greyhound Saramssy at his stirrup. Like Jupiter and Wotan, he throws thunder and lightning, he kills the snake Ahi - of course, he is the prototype of all heroes who defeat dragons and giants, be it Perseus, Tristan or the “brave little tailor”.

Each nation had its own god and its own goddess of love, the sun god, the god of war, the mother goddess of the earth and the god - ruler of the underworld. However, not only the personalities of the gods and heroes are similar, but also the rituals, prayers, dances, and cults. Here is one of the most striking leitmotifs in terms of overall similarity: heroes or saints cope with many trials. He enters into battle with demons and monsters, whether they are creations of his imagination or real phenomena, and when he defeats them thanks to his courage, dexterity, intelligence or other virtues, he learns the great truth and becomes immortal. This pattern, which is present in the epics of a wide variety of religions and mysteries, is noted not only in highly developed cultures. No, it is also found in the legends of the Prairie Indians, the Kirghiz, and the indigenous inhabitants of the central regions of Australia. Scientists paid attention to this circumstance when studying the Iliad and sources related to this work.

Unlike theologians, we believe that the world of the gods arose not only to fulfill cosmic law, but also to convey some basic principles or Platonic ideas. It is also intended to display the great diversity and diversity of images and events that man encounters on earth. In its appearance, the world of the gods is aesthetic, in its manifestations it is sensual. Thus, it connects the real and the spiritual, the mystical and the material, the soul and the surrounding world. In the history of Indian religions, this combination is most clearly expressed in Tantrism, which also seeks harmony between matter and spirit.

Tantrism, as its followers say, fills the gap between physical reality and the inner world; for it there is no contradiction between the organic and the generated spirit. The word “tantrism” comes from the Sanskrit root “tan” - expansion; it is a method of further development of human consciousness, awakening the spiritual forces dormant in a person, attracting them to perform real tasks. Tantrism is not only a theory, but also a practice, it tries to reunite spirit and matter. He proceeds from the premise according to which consciousness and being are the single and only force of personality formation.

It is interesting to note that for the essence of mythology it makes no difference whether we move from bottom to top or from top to bottom. One can descend from the heights of cosmic creations down to the infinite variety of concrete forms that a single spirit takes, or, on the contrary, a person can soar from the sphere of concrete feeling to the heights of universal consciousness. This movement in both directions is an essential characteristic of the world of the gods; in it we see a reflection of both abstract principles and the plastic diversity of human feelings. Hades, Poseidon and Zebe not only represent the past, present and future, but also experience genuine love and military adventures. We see this dualism - the obvious and hidden aspects of the deity - in Indian mythology in the image of Shiva-Shakti: Shiva is the principle of calm, Shakti is the feminine principle - the principle of creative energy, self-disclosure and at the same time knowledge of nature, the active principle thanks to which God the spouse shows his potential qualities. In this striking duality lies total universality.

Just like the Greek world of gods, the teachings of Tantrism rest on a fundamental dualism: the idea of a man is “purusa” (cosmic consciousness) and the idea of a woman is “prakriti” (cosmic force of nature). Purusa acts statically and reflects the transcendental level, prakriti, on the contrary, is kinetic energy, the impulse of creation from which the sensory world arises and develops. Tantrism sees its purpose as integrally connecting polarities in order to experience the joy of realizing the spiritual. The sensual energy of the Greek gods and goddesses, their assertion of infinite cosmic diversity and, above all, their numerous love affairs indicate that the secrets of the love art of the Hindus penetrated into Hellas. Eros sets motionless transcendence in motion, and the meditating Shiva brings it to vibration, creating an eternal connection between the erupting principle and the receiving womb. The world in all its splendor and diversity arises from the unification of the initially contradictory masculine and feminine principles.

This event is finally realized due to the revelation of the cosmic force dormant in man - kundalini. This energy accumulates at the bottom human body, but determines the entire psychophysical essence of a person. To awaken this power, a strict ritual has been developed that stimulates the body's psychic centers (chakras). Kundalini rises through the body from bottom to top up to the highest level of consciousness, giving full disclosure of a person’s capabilities and contributing to their physical realization. In other words, we need to thoroughly shake up the sleeping areas of our brain, in which an infinite number of pictures and ideas have accumulated, but which are used only to a negligible extent. The highest psychic center, in which kundalini is fully revealed, is called tpahas-rava. The process of ascent is accomplished through asana - the union of a man with a woman. Their sexual energy is transformed into a cosmic flow, figuratively speaking, the third eye opens. Thus, Indian mythology transforms erotic feeling into a spiritual principle, and the emphatically amorous pastime of the Greek gods turns out to be necessary for the full disclosure of all their other virtues.

Symbolically, kundalini is depicted as a fiery snake, which in good condition rests motionless in the lower parts of the body. It is easy to see the similarity here with the phallus (linga). It is appropriate to note that mysteries with a snake or phallus were found in abundance in Ancient Greece. The symbols of the snake are Athena, Dmstra, Dionysus, Zeus, Asclespius. The caduceus, the rod of Hermes, is entwined with two vipers; the Pythia in Dslfah, like Kikrey on Salamissus, were snake gods. The followers of Dionysus are also entwined with snakes, they carry a rod, at the end of which there is a pine cone, strongly reminiscent of a phallus. When the skillful Prometheus stole the divine fire, he hid it in a hollow branch and carried it away from Olympus, waving the branch like a snake.

As the antiquity researcher Robert von Ranke-Gravss writes, in the pre-classical era in Greece, male deities were subordinate to the main goddess. But she had her own son as a lover, who is represented either as a serpent of wisdom or as a star of life. Are we not reminded here of Xtzalcoatl, the feathered snake of the Aztecs and Mayans? And in Ancient Egypt the cult of the snake was known. The Book of the Dead says: “And Set, he weaves in my spinal cord... My phallus is the living greeting of Osiris” (meaning that the power of the snake rises in the spinal cord from bottom to top).

The cross on the forehead, which we often see in images of the pharaoh, is the third eye, and the intersection of a vertical line with a circle indicates the connection of the masculine with the feminine. It seems that it is not difficult to prove that the Ursus snake on the head of the Egyptian kings also has a connection with kundalini. The snake was revered by the Gnostics and numerous heretics of the Middle Ages. For the Gnostics, it meant the universe and the continuous cycle of the unfolding of the general from the particular and the return of the general to the particular. Unlike Christian mythology, the Gnostics believed that the snake was the very origin of life, freeing Adam and Eve from the shackles of prejudice. The snake thus becomes the first rebel of world history, who takes away their holy secrets from the gods and introduces people to them.

But snakes often became symbols of protecting secrets and mysteries. This means that they symbolized not only rising energy, but also a demonic, poison-spewing monster. In Greek mythology, serpentine demons guard various objects - symbols of knowledge and cosmic revelations. These are the golden apples of the Hesperides, which Hercules stole, and the golden fleece, which the Argonauts encroached on. As guardian of the sanctuary of Olympia Zeve, Sosipolis appears in the form of a snake to prevent the collapse of the arcades. The dog Ksrbsra, which guards the entrance to hell, has a snake tail. Thus, the fiery snake combines both the demonic and the enlightenment of light, and it is logical to interpret it as a symbol of the path through the labyrinth that the hero must go through in order to achieve higher knowledge. The heroes of the Greek epic - Theseus, Perseus, Hercules, the Argonauts - had to put an end to both external enemies and the internal contradictions that tormented them before reaching a higher level of consciousness.

In Tantrism we also find the idea of using medicinal substances to expand the capabilities of consciousness and facilitate the path to various chakras. Wayne tried to prove that the famous divine drink of the Indians - soma - was obtained from the extract of the fly agaric (amanita imisearia). Tantrics used substances that expand the capabilities of consciousness during certain rituals. They drank "bharig" - a mixture prepared from hemp leaves, or smoked "ganja" - another narcotic drug, or rubbed the ashes of burnt narcotic herbs into their skin.

Greek mythology, especially in all the various mysteries, abounds in magical drinks and witches' cauldrons. The scientist Ranke-Gravss suggests that both goat-footed satyrs and horse-people (centaurs) chewed the fly agaric. At the same time, they experienced hallucinations, acquired the gift of prophecy, and increased muscle strength and sexual potency. On the frame of one Etruscan mirror, a fly agaric is depicted at the feet of Ixion. Ixion was a Thessalian hero who ate ambrosia in the company of the gods. On the Attic vase depicting the centaur Nsss, you can also see a small thin mushroom that grows on cow dung.

The gods, who, strictly speaking, ate only nectar and ambrosia, condemned King Tantalus to eternal hunger precisely because he broke the taboo and distributed ambrosia to mortals. In a book published in 1960, Robert von Ranke-Gravss suggested that ambrosia is a mysterious element of the Orphic, Eleusinian and other mysteries associated with Dionysus. At the same time, all cult participants had to keep in the strictest confidence what they ate. Unforgettable visions opened before their eyes; it seemed that immortality was opening up to them. Ranke-Gravss's assumption has now been confirmed by a detailed study of the Dmstra cult carried out by Hofmann and Wasson. They believe that during the mysteries associated with Demstra, ergot containing LSD was also used.

Just as we find analogies between the cultures of India and America in the image of a feathered or fiery snake, we also find analogies in the use of a small mushroom that grows on dung. The mushroom is called "psilocybe". Now everyone knows about the experiments performed by Huxley, Hofmann, Jungsrs and Gslpx. The experiments of Ranke-Gravss are less known, and they reveal a striking similarity between Indian cults and the mysteries of Ancient Greece. The scientist himself, having taken such a drug, heard the voice of a priestess calling upon the mushroom god Tlaloc. As in Greek myths, Matsatsk legends say that mushrooms appear where lightning strikes.

The snake crown of Dionysus adorns the head of Tlaloc, and just like his Greek “colleague,” Tlaloc, if he had to escape, went to the bottom of the sea. Bloodthirsty local custom tearing off the heads of the victim may have been allegorically derived from the custom of tearing off the caps of sacred mushrooms, because the stems of mushrooms are not eaten in Mexico. Often a toad sits on a mushroom, so the amphibian also became the emblem of Tlaloc. Eroticism and psychedelic plants are the two pillars on which the world of the gods is built throughout the world. We find both elements in the mythology of any people. Only in the materialistic world of the West did they acquire an apocryphal meaning, in particular in the 19th century in bohemian circles, and only in the 60s of our century this combination of basic elements was rediscovered. The man credited with discovering the connection between Tantrism and conscious drug use is Timothy Leary.

Here it is appropriate to recall once again that it was the tantrists who made an attempt to smooth out the contradiction between the external (physical) and internal (spiritual) world. Accordingly, when interpreting myths, there are two approaches: psychological, especially in Jung and Ksreni, and historical, where it is appropriate first of all to mention the name of Ranke-Gravss. Psychologists see in mythology the root causes of the human soul, the most primary forms and norms of life. The psychological world of man is born from myth. “This is a scheme for all times, a spiritual formula that draws its typical features from the subconscious and translates them into the language of practical life” (Thomas Mann). Thus, myth is an arch-stylistic, impersonal reservoir of images from which the human soul draws figures and events. This is the material from which all our dreams are woven, and anyone who wants to deal with the human soul must unravel the myths. Mythology in this sense is called “collective psychology,” “the shared possession of knowable and recognizable images that does not belong to just one person” (Ksrsni).

At the same time, Ranks-Gravss, who, as he admits, was able to penetrate into the essence of the mysteries through special experiments on himself, with the goal of expanding the possibilities of knowledge, sees political-religious history in Greek mythology. For him, the world of the gods fits into a gigantic historical painting conflicts between the principles of patriarchy and matriarchy in Europe. Ancient Europe, according to Ranke-Gravss, did not know any gods, there was only one Great Goddess, and only she was revered as immortal and unchanging. Its power is seen, for example, in the fact that religious ideas did not yet have the concept of fatherhood. The Great Goddess had lovers, but only for her own pleasure. People were in awe of the goddess, they made sacrifices to her and worshiped her. In caves and huts, there was a hearth in the center; it also represented the core of a person’s life at that time, the heart of the community, a symbol of the mystery of primordial motherhood.

Ranke-Graves also looks towards India, in the south of which matrimonial societies still exist, where offspring can only be traced through the mother. Noble women give birth to children from unnoble lovers without a name or title. Thus, Greek myth is primarily the story of the struggle between the traditions of matriarchy, which are supplanted by new forces of conquerors from the north. And Ranks-Gravss easily finds echoes of this historical struggle in any Greek myth.

Let us listen to the tantricist, and he will easily resolve this dispute. He will say: both adherents of the psychological school and adherents of the historical school are right, because our soul is reflected in history, just as history reflects our soul. Subjective and objective are expressions of the same thing, they are only different angles viewpoints under which the same object is viewed. It is difficult for a European to understand this, because the European tradition is based on the fundamental opposition of subject and object.

Ever since Socrates mocked myths in the market square, they began to be relegated to the realm of delusional fantasies. Scholastics, positivists and supporters of Marxist teaching made a significant contribution in this direction. The years of fascism caused especially irreparable damage to the myth. The National Socialists tried to cover up their destructive thirst for power with the screen of a German myth, which existed only in the fevered imagination of fascist ideologists and was devoid of any historical tradition. Runes and Germans, supposedly rediscovered in the thirties, never existed historically. After the collapse of the “thousand-year Reich,” they tried to save the myth by giving it the color of rationalism. But is it possible to tame a monster simply without noticing it?

Again and again attempts are being made to introduce life into a box with only rationalistic shores. But few would argue that rationalism alone is sufficient to interpret mass consciousness our society. The entire history of the 20th century, its political figures are mythologically defined to a greater extent than the world of the ancient Greeks. Such modern myths as atomic energy, biological computers and stations in low-Earth orbit immediately find their adequate reflection in science fiction.

If we recognize that man is involved in the spiritual and the sensual, then there is nothing left to do but recognize the significance of myth, in which history is recorded in sensual form. Of course, positivists and left-wing liberals may disagree with us, but the myth will disappear only when man disappears. Therefore, when interpreting myth politically, it is appropriate not to deny this fact, but to address the question of which myths should be welcomed: paranoid-hybrid or positively lisping. The question is not easy, but before you undertake to answer it, you should study the myth and understand what is hidden behind it and how you can use it to change the world. It is in this sense that we want to present below the figures of Greek mythology.

An attempt to present the psychological and historical sides of a myth, its current and timeless essence, its origin and its aspiration is a very difficult matter, because the study of relationships of this kind has only just begun. And yet, the children of the Earth have already set out on a journey - in search of the ancient art of love, in discovering the secrets of medicinal plants and means that expand the horizons of knowledge.

The course is taught by: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor - Svetlov Roman Viktorovich

Section 1.

The comparative method of studying ancient religions makes sense only if we start from the general, from the primordial basis, which varies in different cultural regions due to the diversity of historical conditions. Such a fundamental principle can be accepted dogmatically (as in the case of the proto-monotheistic theory, which asserts that primitive religions were preceded by prehistoric revelation), but can also be deduced from the available ritual and mythological material. The latter testifies that ancient man perceived the world in the aspect of its formation. The theme of the birth and death of everything in the world, so essential for the consciousness of ancient cultures, leaves an imprint on their perception of the world itself. It turned out to be eternally created and destroyed by supernatural forces, which acquired their own meaning precisely and only in this process of creation and destruction. In other words, ideas about the world, about its spatial, geographical, semantic structures, about society, and finally, ideas about deities were expressed through cosmogonic legends.

By the time the first state civilizations emerged, these legends had already acquired a stable form. They are recorded in rituals that sometimes have national significance, since they were associated with the sacralization of political power received from the demiurge gods (in general, in ritual-myth dualism, ritual plays a leading role; myth is its verbal expression, it pronounces the action). The structure of the cosmogonic myth has a three-part structure. The following steps are clearly distinguished, which, at the same time, are structural moments of the universe: Chaos. Chthonia. Space.

Chaos is the primordial substance that generates the maw-womb, often identified with pre-cosmic waters. There are no qualitative differences in it, it is the Father and Mother of all gods, or all the gods before their separation. Pagan theologians of later eras identified the First Principle with chaotic substance (the One in ancient Neoplatonism. Brahman in traditional Indian culture).

Chthonia is a substance usually figuratively identified with the element of earth. The chthonic principle is generated and released from the chaotic womb. They are personified by the “elder gods” (the Titans of the Hellenes, the Anunnaki of the Sumerians, the Asuras of the Indo-Aryans), who ruled the world in that era of cosmic creation, when the earth and heavens were not yet separated, when there was no separation of the divine and the human, that is, in the era of the “golden age.” century."

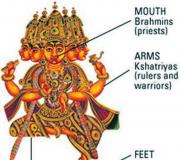

The chthonic element acts as an enemy of the demiurge gods. If the transition from chaos to chthonic is natural, then cosmos is the result of ritual confrontation. One side of the latter is the head of the chthonic gods (for example, Kronos in Hesiod’s Theogony), which can be replaced by an extremely complex, mixanthropic creature, a kind of embryo of the Cosmos (Python of the Hellenes, Pan-gu of the Chinese, Purusha of the Indians). On the other hand, there is the demiurge god, the future head of the cosmos. Depicted in legends as a fight, sometimes accompanied by verbal play, in rituals this situation is revealed as a sacrifice. Indeed, the demiurge (Zeus, Indian Indra, Babylonian Marduk) is a sacrificer, a chthonic being is a victim. The latter is dissected and named, which is already the creation of the Cosmos, the division of earth and heaven, the distribution of parts of the world, the creation of cosmic elements and phenomena, the establishment of the destinies of existence.

Sacrifice means the sanctification of the sacrificed. But, on the other hand, it places guilt on the donor. Its redemption is the establishment and maintenance of cosmic order. Here lies the central point of pagan religions. They are rooted in how man's relationship to the created world is interpreted. In most cases, anthropogenesis repeats cosmogenesis and man is considered as one of the bearers of this guilt. Life in the world below is for him both a gift from the gods and a redemptive act that can lead to deification. In those later religions that treat the world as a place of suffering (Buddhism) or even evil (Gnosticism), a person must atone for his voluntary or involuntary participation in the life of the Cosmos. Thus, pagan religion establishes the connection between man and God through the establishment of the causes of the creation of the world.

The main cosmogonic myth does not point to an event that once happened. The event of world creation is constantly present, forming the semantic and spatial structure of the world. The chaotic is those roots of things that lie in the very depths (literal) of the world and, at the same time, that oceanic flow that embraces the Cosmos (“periphery”, for ancient consciousness the embracing is more primary than the embraced). Chthonic is the depth of the earth, opposite the heavenly Olympus of the cosmic gods. Such, for example, is Tartarus, a place of eternal dying, where the Titans, chthonic rivals of the Hellenic Olympian gods, are imprisoned. Inside the Cosmos, the place of the chthonic element is the underworld: Hades (Hellas), the kingdom of Yama (India), or Osiris (Egypt). Death, therefore, is a departure into the past, into that state of existence when there was no birth or distinction. Hence the semantic opposition of the Top (Heaven) to the Bottom (Counterheaven), which is duplicated by the opposition of the East (where birth occurs) to the West (where the underworld begins). The Earth, as the pre-cosmic parent of everything, also appears in the image of the Universal Mother, the Earth-Mistress (for example, the Phrygian Cybele, which combined the features of the nameless Mistresses of the primitive cultures of Europe and Asia).

The presence of a cosmogonic situation is always expressed in calendar myths. The latter constitute the most famous and interesting layer of ancient religious consciousness in European culture. The tales of Adonis, Osiris, Attis, Tammuz and similar ones are associated with the initiation of earthly fertility, with the change of seasons (hence the name: “calendar”). In the symbols of the dying-rebirth of nature, with the various aspects of which the heroes of such myths are associated, the same cosmogonic structure is revealed, where there is a chthonic victim, and a sacrificer, and death as atonement for ancient guilt, and guilt that turns into salvation. The calendar unfolding of the cosmogonic myth means the perception of what is happening in the world through the ideologeme of eternal return, which creates ancient “cyclical” ideas about history.

The listed features of ancient paganism do not, of course, exhaust its entire content. However, when studying ancient religious cultures, it is necessary to remember that they are a kind of interpretation of the original cosmogonic structure.

Questions for section 1:

The concept of myth.

Myth and religion.

Myth and ritual.

The structure of the cosmogonic myth.

Cosmogony and sacrifice.

Myth and historical time.

Calendar forms of cosmogony.

Anthropogonic myth.

The structure of the human being in the views of archaic cultures.

The concept of paganism.

Tests for section 1.

Temporal, spatial, semantic relations in cosmogonic myth.

The origin of the idea of the cycle of times in archaic cultures.

Forms of cosmogonic myth.

Cosmogenesis and anthropogenesis.

Mystery cults of antiquity. Their connection with the calendar unfolding of the cosmogonic.

Basic literature for section 1.

Archaic ritual in folklore and early literary monuments. M., 1988.

Veselovsky A.N. Historical poetics. M., 1940.

Gritsner P.A. Epic ancient world. M., 1971.

Dumezil J. Gods of the Indo-Europeans. M., 1983.

Evzlin M. Cosmogony and ritual. M., 1993.

Lévi-Strauss K. Primitive thinking. M., 1994.

Lotman Yu.M., Uspensky B.A. Myth-Name-Culture. Tartu. 1973.

Meletinsky E.M. Poetics of myth. M., 1976.

Mythology of the ancient world. M., 1977.

Myths of the peoples of the world: in 2 volumes. M., 21982-84.

Propp V.Ya. Historical roots of fairy tales. L., 1946.

Svetlov E. In search of the path, truth and life: in 6 volumes. Brussels.

Svetlov R. Ancient pagan religiosity. St. Petersburg, 1993.

Toporov V.N. On the cosmological sources of early historical descriptions. Tartu, 1973.

Terneo V. Symbol and ritual. M., 1983.

Fraser J. The Golden Bough. M., 1985.

Fraser J. Volkler in the Old Testament. M., 1989.

Freidenberg O.M. Myth and literature of antiquity. M., 1978.

Elliade M. Space and history. M., 1987.

Eliade M. Sacred and secular. M., 1994.

The course on the history of ancient paganism examines the religious culture of the first state civilizations. Its lower boundary is the centuries of the formation of these civilizations (for example, for Egypt - the turn of the third and fourth millennium BC, for China - the middle of the second millennium BC), and the upper - the century of the appearance of “new religions”: such like Christianity in the Mediterranean, Buddhism in India. The order of studying ancient cultures is not chronological (from more ancient to more modern), but geographical.

What did people talk about ten thousand years ago? What worried them? Comparative mythology allows us to reconstruct elements of the worldview of our distant ancestors and identify the common roots of spiritual culture different nations.

Probably everyone remembers - if a ladybug sits on your hand, you need to ask her: “Ladybug, fly to the sky, bring me bread, black and white, but not burnt.” Different peoples have similar sayings. For example, English children say: “Ladybug, fly home, your house is on fire, your children are in trouble...”, and Norwegians ask her: “Goldenbird, fly east, fly west, fly north, fly to south, find my love." Among the Dutch, a ladybug landing on their hands or clothes is considered a good omen. Linguist Vladimir Toporov studied the names of the ladybug in different languages and came to the conclusion that its image is associated with the ancient beliefs of the Indo-Europeans and their myth about the thunder god, who, suspecting his wife of treason, threw her from the sky. If the assumption is correct that the myth existed before the collapse of the single Proto-Indo-European language into separate branches, then this belief is several thousand years old. That is, each of us in childhood, without knowing it, reproduced a traditional text that has passed through hundreds of generations.

How many such stories have survived? How long do myths last? folk tradition? For thousands of years they have formed a vital part of spiritual culture. Reconstruction of ancient mythologies would provide insight into our ancestors' ideas about the world and themselves. Of course, studying the mythological traditions of the past is possible on the basis of written sources. The scientific sensation of the 19th century was the discovery and deciphering by the curator of the British Museum, George Smith, of the Sumerian legend of the flood, written in hieroglyphs on clay tablets. Analysis of the texts has shown that the biblical legend about Noah coincides in detail (with the exception of some differences) with the more ancient Sumerian story about Utnapishtim. But where did this myth come to the Sumerians? And when did it arise? The oldest Egyptian and Sumerian mythological texts belong to the third, Chinese. to the first millennium BC. e., and the creators of the civilizations of Peru had no written language at all. Does this mean that we will never know how people of the past imagined their world? Could ancient ideas have been preserved in myths that have survived to this day?

The archaeologist offers his answers to these questions Yuri Evgenievich Berezkin, Doctor of Historical Sciences, head of department at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. He developed a method for reconstructing elements of spiritual culture. The idea behind his research is quite simple.

In order to identify ancient myths, it is necessary to compare the mythological traditions of different peoples and identify common elements. For example, the myths and legends of the American Indians and the peoples of Eurasia, who had no contact for thousands of years. Some common themes for them, which the aborigines could not possibly have borrowed from recent European settlers, were known earlier, but no one had conducted a systematic, large-scale search that could reveal very ancient connections before Berezkin. Before the advent of computers, such work was hardly possible.

Yuri Evgenievich Berezkin analyzed more than 30 thousand texts out of 3000 literary sources in eight languages, representing the mythological traditions of the peoples of the New World, Oceania and part of Eurasia, and created Digital catalogue, describing these texts. The history of the creation of this catalog is indicative. Berezkin, an archaeologist by education and vocation, who spent a quarter of a century in excavations on the border of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, in the 90s, due to changes in the political situation and funding of domestic science, in his own words, “orphaned” - was not able to continue archaeological work in the usual way. It was then that, in order not to break away from what he loved, he began collecting a collection of mythological texts. The database he created has no analogues in the world in terms of volume and completeness of description of the material. For each text in the catalog, a brief retelling is provided, and the code designation of myth elements (motives) from the list selected by the researcher is entered into a separate database. This makes it possible to carry out statistical processing of texts and identify similar motifs between the mythological traditions being studied.

In this case, one should take into account both the possibility of a random coincidence, the independent occurrence of similar phenomena among different peoples, and the high probability of borrowing, repeated copying of cultural elements from generation to generation and from one people to another. It is clear that borrowing is more likely for related peoples living close to each other, and less likely for peoples located at great distances from each other. Nevertheless, it was possible to identify more than a dozen common motives.

For example, the story of the Kiowa Indians about the appearance of bison. The hero of the story, Sendeh, a trickster and a deceiver, learns that the White Raven hid all the bison in his cave. Sendeh sneaks into the cave, releases the bison, and so that the Raven standing at the entrance does not kill him, he turns into a burr and sticks to the bison’s belly. Replace Sendeh with Odysseus, the Raven with the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, and the bison with goats and sheep, and you will receive famous story from Greek mythology. It is also found among other nations ( rice. 1). The Kazakh myth is very similar to the Greek one. Burgan-batyr and his comrade are brought into the cave by a one-eyed old man who was going to eat them. The batyr burns out the cannibal’s only eye and hides in a cattle pen. To get out, he puts on the skin of a goat. Animals (not goats, but wild deer and kulans) run away from the cave. Since then, ungulates have roamed the steppe and are hunted by people. Probably, in the Kazakh and American versions, explaining the origin of wild animals, elements that arose before the spread of cattle breeding were preserved, that is, more ancient than the Greek myth. It is interesting that the peoples of Eurasia living east of Mongolia, this myth is missing.

This example, firstly, illustrates the features of reproducing mythological texts. The fact is that the lifespan of the mythological text itself on a historical scale is not too long. But the elements that make up these texts (certain character traits or certain plot twists) turn out to be quite stable. From these elements we will call them mythological motifs, in different combinations, like from a mosaic, new texts are assembled, the meaning and details of which may vary in different traditions and even within the same tradition.

Secondly, it provides an opportunity to discuss three options for explaining the similarity of myths among peoples so distant historically and geographically.

First- the presence of universal forms of thinking, similar to Jungian archetypes, which are reflected in myths. But, as an analysis of a huge corpus of mythological texts has shown, motifs that could reflect universal psychological characteristics of all people on all continents, are characteristic of some territories and completely uncharacteristic of others.

Second possibility- is the appearance of similar myths in similar natural or social conditions. Of course, there is a rational grain in such an approach. But in the end, both the social and natural environment only sets some restrictions, leaving freedom for countless variations. For example, it is clear that only in low latitudes, where the crescent moon is located horizontally, is it associated with a boat, but in the Arctic there is no image of a moon-boat. However, even in the tropics, such an image is quite rare and, moreover, is found only in certain areas.

Place of first publication: journal “Chemistry and Life”, 2006, No. 3, www.hij.ru

A. N. Veselovsky. Favorites. On the way to historical poetics M.: "Autokniga", 2010. - (Series "Russian Propylaea")

Comparative mythology and its method

Zoological Mythology, by Angelo De Gubernatis. London. Trübner. 1872. 2 w.