The ancient Indian population consisted of the following castes. Life and occupation of Varna Brahmins in ancient and modern India

Caste is the original civilizational model,

built on its own conscious principles.

L. Dumont “Homo Hierarchicus”

The social structure of the modern Indian state is unique in many ways, primarily due to the fact that, like several thousand years ago, it is still based on the existence of a caste system, which is one of its main components.

The word “caste” itself appeared later than the social stratification of ancient Indian society began. Initially the term "varna" was used. The word "varna" is of Indian origin and means color, mode, essence. In the later laws of Manu, instead of the word “varna”, the word “jati” was sometimes used, meaning birth, gender, position. Subsequently, in the process of economic and social development, each varna was divided into a large number of castes; in modern India there are thousands of them. Contrary to popular belief, the caste system in India has not been abolished, but still exists; Only discrimination on the basis of caste is abolished by law.

Varna

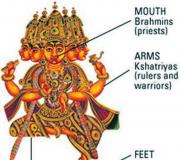

In ancient India there were four main varnas (chaturvarnya), or classes. The highest varna - brahmans - are priests, clergymen; their duties included studying sacred texts, teaching people and performing religious rites, since they were considered to have the proper holiness and purity.

In ancient India there were four main varnas (chaturvarnya), or classes. The highest varna - brahmans - are priests, clergymen; their duties included studying sacred texts, teaching people and performing religious rites, since they were considered to have the proper holiness and purity.

The next varna is the kshatriyas; these are warriors and rulers who had the necessary qualities (for example, courage and strength) to govern and protect the state.

They are followed by Vaishyas (merchants and farmers) and Shudras (servants and laborers). The attitude to the last, fourth varna is told in the ancient legend about the creation of the world, which says that at first three varnas were created by God - brahmanas, kshatriyas and vaishyas, and later people (praja) and cattle were born.

The first three varnas were considered the highest, and their representatives were “twice-born”. The physical, “first” birth was only a door to this earthly world, however, for internal growth and spiritual development, a person had to be born a second time - anew. This meant that representatives of privileged varnas underwent a special rite - initiation (upanayana), after which they became full members of society and could learn the profession that they inherited from representatives of their clan. During the ritual, a cord of a certain color and material, prescribed in accordance with the tradition of this varna, was placed around the neck of a representative of a given varna.

It was believed that all varnas were created from the body of the first man - Purusha: brahmanas - from his mouth (the color of this varna is white), kshatriyas - from his hands (the color is red), vaishyas - from the thighs (the color of varna is yellow), shudras - from his feet (black color).

The “pragmatism” of such a class division lay in the fact that initially, as is assumed, a person’s assignment to a certain varna occurred as a result of his natural inclinations and inclinations. For example, a brahmana became one who could think with his head (therefore the symbol is the mouth of Purusha), who himself had the ability to learn and could teach others. A Kshatriya is a person with a warlike nature, more inclined to work with his hands (that is, to fight, therefore the symbol is the hands of Purusha), etc.

Shudras were the lowest varna, they could not participate in religious rituals and study the sacred texts of Hinduism (Vedas, Upanishads, Brahmins and Aranyakas), they often did not have their own household, and they were engaged in the most difficult types of labor. Their duty was unconditional obedience to the representatives of the higher varnas. The Shudras remained “once-born,” that is, they did not have the privilege of rebirth to a new, spiritual life (probably because their level of consciousness was not ready for this).

Varnas were absolutely autonomous, marriages could only take place within a varna, the mixing of varnas, according to the ancient laws of Manu, was not allowed, as well as the transition from one varna to another - higher or lower. Such a rigid hierarchical structure was not only protected by laws and tradition, but was directly related to the key idea of the Indian religion - the idea of reincarnation: “As childhood, youth and old age come to the incarnate here, so does a new body come: a sage cannot be puzzled by this” ( Bhagavad Gita).

It was believed that being in a certain varna is a consequence of karma, that is, the cumulative result of one’s actions and deeds in past lives. The better a person behaved in past lives, the more chances he had to incarnate in a higher varna in his next life. After all, varna affiliation was given by birth and could not change throughout a person’s life. This may seem strange to a modern Westerner, but such a concept, completely dominant in India for several millennia until today, created, on the one hand, the basis for the political stability of society, on the other, it was a moral code for huge sections of the population.

Therefore, the fact that the varna structure is invisibly present in the life of modern India (the caste system is officially enshrined in the main law of the country) is most likely directly related to the strength of religious convictions and beliefs that have stood the test of time and have remained almost unchanged to this day.

But is the secret of the “survivability” of the varna system only in the power of religious ideas? Perhaps ancient India managed to somewhat anticipate the structure of modern societies, and it is no coincidence that L. Dumont calls castes a civilizational model?

A modern interpretation of the varna division might look, for example, like this.

Brahmins are people of knowledge, those who receive knowledge, teach it and develop new knowledge. Since in modern “knowledge” societies (a term officially adopted by UNESCO), which have already replaced information societies, not only information, but knowledge is gradually becoming the most valuable capital, surpassing all material analogues, it becomes clear that people of knowledge belong to the highest strata of society .

Kshatriyas are people of duty, senior managers, government-level administrators, military personnel and representatives of the “security agencies” - those who guarantee law and order and serve their people and their country.

Vaishyas are people of action, businessmen, creators and organizers of their business, whose main goal is to make a profit; they create a product that is in demand in the market. Vaishyas now, just like in ancient times, “feed” other varnas, creating the material basis for the economic growth of the state.

Shudras are people for hire, hired workers, for whom it is easier not to take responsibility, but to carry out the work assigned to them under the control of management.

Living “in your varna,” from this point of view, means living in accordance with your natural abilities, innate predisposition to a certain type of activity and in accordance with your calling in this life. This can give a feeling of inner peace and satisfaction that a person is living his own, and not someone else’s, life and destiny (dharma). It is not for nothing that the importance of following one’s dharma, or duty, is spoken of in one of the sacred texts included in the Hindu canon - the Bhagavad Gita: “It is better to fulfill one’s duties, even imperfectly, than the duties of others perfectly. It’s better to die doing your duty; someone else’s path is dangerous.”

In this “cosmic” aspect, the varna division looks like a completely pragmatic system for realizing a kind of “call of the soul”, or, in higher language, fulfilling one’s destiny (duty, mission, task, calling, dharma).

The Untouchables

In ancient India there was a group of people who were not part of any of the varnas - the so-called untouchables, who de facto still exist in India. The emphasis on the actual state of affairs is made because the situation with the untouchables in real life is somewhat different from the legal formalization of the caste system in modern India.

The untouchables in ancient India were a special group that performed work associated with the then ideas about ritual impurity, for example, dressing animal skins, collecting garbage, and corpses.

In modern India, the term untouchables is not officially used, as are its analogues: harijan - “children of God” (a concept introduced by Mahatma Gandhi) or pariah (“outcast”) and others. Instead, there is a concept of Dalit, which is not believed to carry the connotation of caste discrimination prohibited in the Indian Constitution. According to the 2001 census, Dalits constitute 16.2% of India's total population and 79.8% of the total rural population.

Although the Indian Constitution has abolished the concept of untouchability, ancient traditions continue to dominate the mass consciousness, which even leads to the killing of untouchables under various pretexts. At the same time, there are cases when a person belonging to a “pure” caste is ostracized for daring to do “dirty” work. Thus, Pinky Rajak, a 22-year-old woman from the caste of Indian washerwomen, who traditionally wash and iron clothes, caused outrage among the elders of her caste because she began cleaning at a local school, that is, she violated the strict caste ban on dirty work, thereby insulting her community.

Castes Today

To protect certain castes from discrimination, there are various privileges provided to citizens of lower castes, such as reservation of seats in legislatures and civil service, partial or full tuition fees in schools and colleges, quotas in higher educational institutions. In order to avail the right to such a benefit, a citizen belonging to a state-protected caste must obtain and present a special caste certificate - proof of his membership in a particular caste listed in the caste table, which is part of the Constitution of India.

Today in India, belonging to a high caste by birth does not automatically mean a high level of material security. Often, children from poor families of the upper castes, who enter college or university on a general basis with great competition, have much less chance of getting an education than children from lower castes.

The debate about actual discrimination against upper castes has been going on for many years. There are opinions that in modern India there is a gradual erosion of caste boundaries. Indeed, it is now almost impossible to determine which caste an Indian belongs to (especially in large cities), not only by appearance, but often by the nature of his professional activity.

Creation of national elites

The formation of the structure of the Indian state in the form in which it is presented now (developed democracy, parliamentary republic) began in the 20th century.

In 1919, the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms were carried out, the main goal of which was the establishment and development of a system of local government. Under the English governor-general, who had previously virtually ruled the Indian colony single-handedly, a bicameral legislative body was created. In all Indian provinces, a system of dual power (diarchy) was created, when both representatives of the English administration and representatives of the local Indian population were in charge. Thus, at the very beginning of the twentieth century, democratic procedures were introduced for the first time on the Asian continent. The British, unwittingly, contributed to the formation of the future independence of India.

After India gained independence, the need arose to attract national personnel to lead the country. Since only the educated strata of Indian society had a real opportunity to “restart” social institutions under conditions of independence, it is clear that the leading role in governing the country mainly belonged to the brahmins and kshatriyas. That is why the unification of the new elites was practically conflict-free, since the brahmins and kshatriyas historically belonged to the highest castes.

Since 1920, the popularity of Mahatma Gandhi, who advocated a united India without the British, began to grow. The Indian National Congress, which he headed, was not so much a party as a national social movement. Gandhi managed to accomplish something that no one had succeeded before - albeit temporarily, but he practically eliminated the conflict of interests between the higher and lower castes.

What tomorrow?

In India in the Middle Ages there were no cities similar to European ones. These cities could rather be called large villages, where time seemed to stand still. Until recently (especially intensive changes began to occur in the last 15–20 years), tourists coming from the West could feel themselves in a medieval atmosphere. Real changes began after independence. The course towards industrialization taken in the second half of the twentieth century caused an increase in the rate of economic growth, which, in turn, led to an increase in the share of the urban population and the emergence of new social groups.

Over the past 15–20 years, many Indian cities have changed beyond recognition. Most of the almost “homey” neighborhoods in the center turned into concrete jungles, and the poor neighborhoods on the outskirts were transformed into residential areas for the middle class.

According to forecasts, by 2028, India's population will exceed 1.5 billion people, the largest percentage of them will be young people and, compared to Western countries, the country will have the largest labor force.

Today, in many countries there is a shortage of qualified personnel in the field of medicine, education and IT services. This situation has contributed to the development in India of such a rapidly growing economic sector as the provision of remote services, for example in the United States and Western European countries. The Indian government is now investing heavily in education, especially in schools. You can see with your own eyes how in the mountainous regions of the Himalayas, where 15-20 years ago there were only remote villages, state technological colleges have grown up in large areas, with beautiful buildings and infrastructure, intended for local children from the same villages. The bet on education in the age of “knowledge” societies, especially on school and university education, is a win-win, and it is no coincidence that India occupies one of the leading places in the field of computer technology.

This projection of Indian population growth could be optimistic for India and lead to significant economic growth as well. But growth doesn't happen by itself. It is necessary to create conditions: new jobs, ensuring industrial employment and, no less important, providing qualified training to all this huge mass of human resources. All this is not an easy task and is more of a challenge for the state than a bonus. If the necessary conditions are not met, there will be mass unemployment, a sharp decline in the living standards of the population and, as a consequence, negative changes in the social structure.

Until now, the existing caste system has been a kind of “fuse” against various kinds of social upheavals throughout the country. However, times are changing, Western technologies are intensively penetrating not only the Indian economy, but into the consciousness and subconscious of the masses, especially in cities, forming a new, non-traditional for many Indians model of desires according to the principle “I want more now.” This model is intended primarily for the so-called middle class (“so-called” because for India its boundaries are blurred and the criteria for membership are not entirely clear). The question of whether the caste system can still serve as a protector against social cataclysms in the new conditions remains open.

The untouchable caste in India is a phenomenon that cannot be found in any other country in the world. Originating in ancient times, the caste division of society exists in the country to this day. The lowest level in the hierarchy is occupied by the untouchable caste, which includes 16-17% of the country's population. Its representatives constitute the “bottom” of Indian society. Caste structure is a complex issue, but let’s try to shed light on some of its aspects.

Caste structure of Indian society

Despite the difficulty of reconstructing a complete structural picture of castes in the distant past, it is still possible to identify historical groups in India. There are five of them.

The highest group (varna) of brahmanas includes civil servants, large and small landowners, and priests.

Next comes the Kshatriya varna, which included the military and agricultural castes - Rajaputs, Jats, Marathas, Kunbis, Reddis, Kapus, etc. Some of them form a feudal stratum, the representatives of which later join the lower and middle ranks of the feudal class.

The next two groups (vaishyas and sudras) include the middle and lower castes of farmers, officials, artisans, and community servants.

And finally, the fifth group. It includes the castes of community servants and farmers, deprived of all rights to own and use land. They are called untouchables.

“India”, “untouchable caste” are concepts inextricably linked with each other in the minds of the world community. Meanwhile, in a country with an ancient culture, they continue to honor the customs and traditions of their ancestors in dividing people according to their origin and belonging to some caste.

The history of the untouchables

The lowest caste in India - the untouchables - owes its appearance to the historical process that took place in the region in the Middle Ages. At that time, India was conquered by stronger and more civilized tribes. Naturally, the invaders came to the country with the aim of enslaving its indigenous population, preparing for them the role of servants.

To isolate the Indians, they were settled in special settlements built separately, similar to modern ghettos. Civilized outsiders did not allow the natives into their community.

It is assumed that it was the descendants of these tribes who subsequently formed the untouchable caste. It included farmers and servants of the community.

True, today the word “untouchables” has been replaced by another - “Dalits”, which means “oppressed”. It is believed that "untouchables" sounds offensive.

Since Indians often use the word "jati" rather than "caste", their number is difficult to determine. But still, Dalits can be divided by occupation and place of residence.

How do untouchables live?

The most common Dalit castes are Chamars (tanners), Dhobis (washerwomen) and Pariahs. If the first two castes have some kind of profession, then the pariahs live only on unskilled labor - removing household waste, cleaning and washing toilets.

Hard and dirty work is the fate of the untouchables. The lack of any qualifications brings them a meager income, allowing only

However, among the untouchables there are groups that are at the top of the caste, such as the hijras.

These are representatives of all kinds of sexual minorities who engage in prostitution and begging. They are also often invited to all kinds of religious rituals, weddings, and birthdays. Of course, this group has much more to live on than the untouchable tanner or laundress.

But such an existence could not but cause protest among the Dalits.

Protest struggle of the untouchables

Surprisingly, the untouchables did not resist the tradition of division into castes imposed by the invaders. However, in the last century the situation changed: the untouchables, under the leadership of Gandhi, made the first attempts to destroy the stereotype that had developed over centuries.

The essence of these performances was to draw public attention to caste inequality in India.

Interestingly, Gandhi's cause was taken up by a certain Ambedkar from the Brahmin caste. Thanks to him, the untouchables became Dalits. Ambedkar ensured that they received quotas for all types of professional activities. That is, an attempt was made to integrate these people into society.

Today's controversial policies of the Indian government often cause conflicts involving untouchables.

However, it does not come to a riot, because the untouchable caste in India is the most submissive part of the Indian community. The age-old timidity of other castes, ingrained in the consciousness of people, blocks any thoughts of rebellion.

Indian Government Policy and Dalits

The untouchables... The life of the harshest caste in India evokes a cautious and even contradictory reaction from the outside, since we are talking about the age-old traditions of the Indians.

But still, caste discrimination is prohibited at the state level in the country. Actions that offend representatives of any varna are considered a crime.

At the same time, the caste hierarchy is legalized by the country's constitution. That is, the untouchable caste in India is recognized by the state, which looks like a serious contradiction in government policy. As a result, the modern history of the country has many serious conflicts between and even within individual castes.

The untouchables are the most despised class in India. However, other citizens are still terribly afraid of Dalits.

It is believed that a representative of an untouchable caste in India is capable of desecrating a person from another varna by his very presence. If a Dalit touches the clothes of a Brahman, the latter will need more than one year to cleanse his karma of filth.

But an untouchable (the caste of South India includes both men and women) may well become the object of sexual violence. And no defilement of karma occurs in this case, since this is not prohibited by Indian customs.

An example is the recent case in New Delhi, where a 14-year-old untouchable girl was kept as a sex slave for a month by a criminal. The unfortunate woman died in the hospital, and the detained criminal was released by the court on bail.

At the same time, if an untouchable violates the traditions of his ancestors, for example, he dares to publicly use a public well, then the poor fellow will face swift reprisals on the spot.

Dalit is not a sentence of fate

The untouchable caste in India, despite government policies, still remains the poorest and most disadvantaged part of the population. The average literacy rate among them is a little over 30.

The situation is explained by the humiliation that children of this caste are subjected to in educational institutions. As a result, illiterate Dalits constitute the bulk of the unemployed in the country.

However, there are exceptions to the rule: about 30 millionaires in the country are Dalits. Of course, this is tiny compared to the 170 million untouchables. But this fact says that Dalit is not a decree of fate.

An example is the life of Ashok Khade, who belonged to the tanner caste. The guy worked as a docker during the day and studied textbooks at night to become an engineer. His company currently closes deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

There is also the opportunity to leave the Dalit caste - this is a change of religion.

Buddhism, Christianity, Islam - any faith technically takes a person out of the untouchables. This was first used at the end of the 19th century, and in 2007, 50 thousand people immediately accepted Buddhism.

Hello, dear readers – seekers of knowledge and truth!

Many of us have heard about castes in India. This is not an exotic system of society that is a relic of the past. This is the reality that the people of India live in even today. If you want to learn as much as possible about Indian castes, today’s article is especially for you.

She will tell you how the concepts of “caste”, “varna” and “jati” are related, why the caste division of society arose, how castes appeared, what they were like in ancient times, and what they are like now. You will also learn how many castes and varnas there are today, and also how to determine an Indian’s caste.

Caste and Varna

In world history, the concept of “caste” originally referred to Latin American colonies, which were divided into groups. But now, in people's minds, caste is strongly associated with Indian society.

Scientists - Indologists, orientalists - have been studying this unique phenomenon for many years, which does not lose its power after thousands of years, they write scientific works about it. The first thing they say is that there is caste and there is varna, and these are not synonymous concepts.

There are only four Varnas, and there are thousands of castes. Each varna is divided into many castes, or, in other words, “jatis”.

The last census, which took place in the first half of the last century, in 1931, counted more than three thousand castes throughout India. Experts say that their number is growing every year, but cannot give an exact figure.

The concept of “varna” has its roots in Sanskrit and is translated as “quality” or “color” - based on the specific color of clothing worn by representatives of each varna. Varna is a broader term that defines position in society, and caste or “jati” is a subgroup of varna, which indicates membership in a religious community, occupation by inheritance.

A simple and understandable analogy can be drawn. For example, let’s take a fairly wealthy segment of the population. People growing up in such families do not become the same in occupation and interests, but occupy approximately the same status in material terms.

They can become successful businessmen, representatives of the cultural elite, philanthropists, travelers or people of art - these are the so-called castes, passed through the prism of Western sociology.

From the very beginning until today, Indians have been divided into only four varnas:

- brahmins - priests, clergy; upper layer;

- kshatriyas - warriors who guarded the state, participated in battles and battles;

- Vaishya - farmers, cattle breeders and traders;

- Shudras - workers, servants; lower layer.

Each varna, in turn, was divided into countless castes. For example, among the kshatriyas there could be rulers, rajas, generals, warriors, policemen and further on the list.

There are members of society who cannot be included in any of the varnas - this is the so-called untouchable caste. At the same time, they can also be divided into subgroups. This means that a resident of India may not belong to any varna, but he must belong to a caste.

Varnas and castes unite people by religion, type of activity, profession, which are inherited - a sort of strictly regulated division of labor. These groups are closed to members of lower castes. An unequal marriage in Indian style is a marriage between representatives of different castes.

One of the reasons why castesystemso strong is the Indian belief in rebirth. They are convinced that by strictly observing all the regulations within their caste, in their next birth they can incarnate as a representative of a higher caste. Brahmins have already gone through their entire life cycle and will certainly incarnate on one of the divine planets.

Characteristics of castes

All castes follow certain rules:

- one religious affiliation;

- one profession;

- certain property they may possess;

- regulated list of rights;

- endogamy - marriages can only take place within a caste;

- heredity - belonging to a caste is determined from birth and is inherited from parents, you cannot move to a higher caste;

- the impossibility of physical contact, sharing food with representatives of lower castes;

- allowed food: meat or vegetarian, raw or cooked;

- color of clothes;

- the color of the bindi and tilak are the dots on the forehead.

Historical excursion

The varna system was entrenched in the Laws of Manu. Hindus believe that we all descended from Manu, because it was he who was saved from flooding thanks to the god Vishnu, while other people died. Believers claim that this happened about thirty thousand years ago, but skeptic scientists call another date - the 2nd century BC.

In the laws of Manu, with amazing accuracy and prudence, all the rules of life are described to the smallest detail: starting with how to swaddle newborns, ending with how to properly cultivate rice fields. It also talks about the division of people into 4 classes, already known to us.

Vedic literature, including the Rigveda, also says that all the inhabitants of ancient India were divided back in the 15th-12th centuries BC into 4 groups that emerged from the body of the god Brahma:

- brahmins - from the lips;

- kshatriyas—from the palms;

- vaishya—from the thighs;

- sudras - from the legs.

Clothing of the ancient Indians

Clothing of the ancient Indians

There were several reasons for this division. One of them is the fact that the Aryans who came to Indian soil considered themselves to be a superior race and wanted to be among people like themselves, abstracting from the ignorant poor people who did what they considered “dirty” work.

Even the Aryans married exclusively women of the Brahman family. They divided the rest hierarchically according to skin color, profession, class - this is how the name “Varna” appeared.

In the Middle Ages, when Buddhism weakened in the Indian expanses and Hinduism spread everywhere, even greater fragmentation occurred within each varna, and from here castes, also known as jati, were born.

Thus, the rigid social structure became even more entrenched in India. No historical vicissitudes, neither the Muslim raids and the resulting Mughal Empire, nor the English expansion could prevent it.

How to distinguish people of different varnas

Brahmins

This is the highest varna, the class of priests and clergy. With the development of spirituality and the spread of religion, their role only increased.

The rules in society prescribed to honor the brahmins and give them generous gifts. The rulers chose them as their closest advisers and judges, appointing high ranks. At the present time, brahmanas are temple servants, teachers, and spiritual mentors.

TodayBrahmins occupy about three-quarters of all government posts. For the murder of a representative of Brahmanism, both then and now, the terrible death penalty invariably followed.

Brahmins are prohibited from:

- engage in agriculture and housekeeping (but Brahmin women can do housework);

- marry representatives of other classes;

- eat what a person from another group has prepared;

- eat animal products.

Kshatriyas

Translated, this varna means “people of power, nobility.” They are engaged in military affairs, govern the state, protect the Brahmins who are higher in the hierarchy, and their subjects: children, women, old people, cows - the country as a whole.

Today, the Kshatriya class consists of warriors, soldiers, guards, police, and leadership positions. Modern Kshatriyas also include the Jat caste, which includes the famous - these long-bearded men with a turban on their heads are found not only in their native state of Punjab, but throughout India.

A kshatriya can marry a woman from a lower varna, but girls cannot choose a husband of a lower rank.

Vaishya

Vaishyas are a group of landowners, cattle breeders, and traders. They also traded in crafts and everything related to profit - for this the Vaishyas earned the respect of the entire society.

Now they are also involved in analytics, business, the banking and financial side of life, and trading. This is also the main segment of the population that works in offices.

Vaishyas have never liked hard physical labor and dirty work - for this they have shudras. In addition, they are very picky when it comes to cooking and preparing dishes.

Shudras

In other words, these were people who performed the most menial jobs and were often below the poverty line. They serve other classes, work in the land, sometimes performing the function of almost slaves.

Shudras did not have the right to accumulate property, so they did not have their own housing and plots. They could not pray, much less become “twice-born,” that is, “dvija,” like the brahmanas, kshatriyas and vaishyas. But Shudras can even marry a divorced girl.

Dvija are men who, as children, underwent the Upanyan initiation rite. After it, a person can perform religious rituals, so upanyan is considered a second birth. Women and Shudras are not allowed to visit him.

The Untouchables

A separate caste that cannot be classified as one of the four varnas is the untouchables. For a long time they experienced all kinds of persecution and even hatred from other Indians. And all because, in the view of Hinduism, untouchables in a past life led an unrighteous, sinful lifestyle, for which they were punished.

They are somewhere beyond this world and are not even considered people in the full sense of the word. These are mainly beggars who live on the streets, in slums and isolated ghettos, and rummage through garbage dumps. At best, they do the dirtiest work: they clean toilets, sewage, animal corpses, work as gravediggers, tanners, and burn dead animals.

Moreover, the number of untouchables reaches 15-17 percent of the total population of the country, that is, approximately every sixth Indian is an untouchable.

The caste “outside society” was prohibited from appearing in public places: schools, hospitals, transport, temples, shops. They were not only forbidden to approach others, but also to step on their shadows. And the Brahmins were offended by the mere presence of an untouchable in sight.

The term used for untouchables is Dalit, which means oppression.

Fortunately, in modern India, everything is changing - discrimination against untouchables is prohibited at the legislative level, now they can appear everywhere, receive education and medical care.

The only thing worse than being born an untouchable is being born a pariah - another subgroup of people who are completely erased from public life. They become the children of pariahs and inter-caste spouses, but there were times when just touching a pariah made a person the same.

Modernity

Some people in the Western world may think that the caste system in India is a thing of the past, but this is far from the truth. The number of castes is increasing, and this is the cornerstone among representatives of the authorities and ordinary people.

The diversity of castes can sometimes surprise, for example:

- jinvar – carry water;

- bhatra - brahmanas who earn money by alms;

- bhangi - remove garbage from the streets;

- darzi - sew clothes.

Many are inclined to believe that castes are evil because they discriminate against entire groups of people and infringe on their rights. During the election campaign, many politicians use this trick - they declare the fight against caste inequality as the main direction of their activities.

Of course, the division into castes is gradually losing its significance for people as citizens of the state, but still plays a significant role in interpersonal and religious relations, for example, in matters of marriage or cooperation in business.

The Government of India is doing a lot for the equality of all castes: they are legally equal, and absolutely all citizens are entitled to vote. Now the career of an Indian, especially in large cities, may depend not only on his origin, but also on personal merit, knowledge, and experience.

Even Dalits have the opportunity to build a brilliant career, including in the government apparatus. An excellent example of this is President Kocheril Raman Narayanan, from a family of untouchables, elected in 1997. Another confirmation of this is the untouchable Bhim Rao Ambedkar, who received a law degree in England and subsequently created the Constitution of 1950.

It contains a special Table of Castes and every citizen can, if he wishes, obtain a certificate indicating his caste in accordance with this table. The Constitution stipulates that government agencies do not have the right to inquire into what caste a person belongs to if he himself does not want to talk about it.

Conclusion

Thank you very much for your attention, dear readers! I would like to believe that the answers to your questions about Indian castes were comprehensive, and the article told you a lot of new things.

See you soon!

September 28th, 2015

Indian society is divided into classes called castes. This division occurred many thousands of years ago and continues to this day. Hindus believe that by following the rules established in your caste, in your next life you can be born as a representative of a slightly higher and more respected caste, and occupy a much better position in society.

Having left the Indus Valley, the Indian Aryans conquered the country along the Ganges and founded many states here, whose population consisted of two classes that differed in legal and financial status. The new Aryan settlers, the victors, seized land, honor, and power in India, and the defeated non-Indo-European natives were plunged into contempt and humiliation, forced into slavery or into a dependent state, or, driven into the forests and mountains, they lived there in inaction thoughts of a meager life without any culture. This result of the Aryan conquest gave rise to the origin of the four main Indian castes (varnas).

Those original inhabitants of India who were subdued by the power of the sword suffered the fate of captives and became mere slaves. The Indians, who submitted voluntarily, renounced their father's gods, adopted the language, laws and customs of the victors, retained personal freedom, but lost all land property and had to live as workers on the estates of the Aryans, servants and porters, in the houses of rich people. From them came the Shudra caste. "Sudra" is not a Sanskrit word. Before becoming the name of one of the Indian castes, it was probably the name of some people. The Aryans considered it beneath their dignity to enter into marriage unions with representatives of the Shudra caste. Shudra women were only concubines among the Aryans.

Over time, sharp differences in status and professions emerged between the Aryan conquerors of India themselves. But in relation to the lower caste - the dark-skinned, subjugated native population - they all remained a privileged class. Only the Aryans had the right to read the sacred books; only they were consecrated by a solemn ceremony: a sacred thread was placed on the Aryan, making him “reborn” (or “twice-born”, dvija). This ritual served as a symbolic distinction between all Aryans and the Shudra caste and the despised native tribes driven into the forests. Consecration was performed by placing a cord, which was worn placed on the right shoulder and descending diagonally across the chest. Among the Brahmin caste, the cord could be placed on a boy from 8 to 15 years old, and it is made of cotton yarn; among the Kshatriya caste, who received it no earlier than the 11th year, it was made from kusha (Indian spinning plant), and among the Vaishya caste, who received it no earlier than the 12th year, it was made of wool.

The "twice-born" Aryans were divided over time, according to differences in occupation and origin, into three estates or castes, with some similarities to the three estates of medieval Europe: the clergy, the nobility and the urban middle class. The beginnings of the caste system among the Aryans existed back in the days when they lived only in the Indus basin: there, from the mass of the agricultural and pastoral population, warlike princes of the tribes, surrounded by people skilled in military affairs, as well as priests who performed sacrificial rites, already stood out.

When the Aryan tribes moved further into India, into the country of the Ganges, militant energy increased in bloody wars with the exterminated natives, and then in a fierce struggle between the Aryan tribes. Until the conquests were completed, the entire people were busy with military affairs. Only when the peaceful possession of the conquered country began did it become possible for a variety of occupations to develop, the possibility of choosing between different professions arose, and a new stage in the origin of castes began. The fertility of the Indian soil aroused the desire for peaceful means of subsistence. From this, the innate tendency of the Aryans quickly developed, according to which it was more pleasant for them to work quietly and enjoy the fruits of their labor than to make difficult military efforts. Therefore, a significant part of the settlers (“vishes”) turned to agriculture, which produced abundant harvests, leaving the fight against enemies and the protection of the country to the princes of the tribes and the military nobility formed during the period of conquest. This class, engaged in arable farming and partly shepherding, soon grew so that among the Aryans, as in Western Europe, it formed the vast majority of the population. Therefore, the name Vaishya “settler”, which originally designated all Aryan inhabitants in new areas, began to designate only people of the third, working Indian caste, and warriors, kshatriyas and priests, brahmans (“prayers”), who over time became privileged classes, made the names of their professions with the names of the two highest castes.

The four Indian classes listed above became completely closed castes (varnas) only when Brahmanism rose above the ancient service to Indra and other gods of nature - a new religious doctrine about Brahma, the soul of the universe, the source of life from which all beings originated and to which they will return. This reformed creed gave religious sanctity to the division of the Indian nation into castes, especially the priestly caste. It said that in the cycle of life forms passed through by everything existing on earth, Brahman is the highest form of existence. According to the dogma of rebirth and transmigration of souls, a creature born in human form must go through all four castes in turn: to be a Shudra, a Vaishya, a Kshatriya and, finally, a Brahman; having passed through these forms of existence, it is reunited with Brahma. The only way to achieve this goal is for a person, constantly striving for deity, to exactly fulfill everything commanded by the brahmanas, to honor them, to please them with gifts and signs of respect. Offenses against Brahmanas, severely punished on earth, subject the wicked to the most terrible torments of hell and rebirth in the forms of despised animals.

The belief in the dependence of the future life on the present was the main support of the Indian caste division and the rule of the priests. The more decisively the Brahman clergy placed the dogma of transmigration of souls at the center of all moral teaching, the more successfully it filled the imagination of the people with terrible pictures of hellish torment, the more honor and influence it acquired. Representatives of the highest caste of Brahmins are close to the gods; they know the path leading to Brahma; their prayers, sacrifices, holy feats of their asceticism have magical power over the gods, the gods have to fulfill their will; bliss and suffering in the future life depend on them. It is not surprising that with the development of religiosity among the Indians, the power of the Brahman caste increased, tirelessly praising in its holy teachings respect and generosity towards the Brahmans as the surest ways to obtain bliss, instilling in the kings that the ruler is obliged to have Brahmans as his advisers and make judges, is obliged to reward their service with rich content and pious gifts.

So that the lower Indian castes did not envy the privileged position of the Brahmans and did not encroach on it, the doctrine was developed and strenuously preached that the forms of life for all beings are predetermined by Brahma, and that the progression through the degrees of human rebirth is accomplished only by a calm, peaceful life in the given position of man, the right one. performance of duties. Thus, in one of the oldest parts of the Mahabharata it is said: “When Brahma created beings, he gave them their occupations, each caste a special activity: for the brahmanas - the study of the high Vedas, for the warriors - heroism, for the vaishyas - the art of labor, for the shudras - humility before other flowers: therefore ignorant Brahmanas, unglorious warriors, unskillful Vaishyas and disobedient Shudras are worthy of blame.”

This dogma, which attributed divine origin to every caste, every profession, consoled the humiliated and despised in the insults and deprivations of their present life with the hope of an improvement in their lot in a future existence. He gave religious sanctification to the Indian caste hierarchy. The division of people into four classes, unequal in their rights, was from this point of view an eternal, unchangeable law, the violation of which is the most criminal sin. People do not have the right to overthrow the caste barriers established between them by God himself; They can achieve improvement in their fate only through patient submission.

The mutual relations between the Indian castes were clearly characterized by the teaching; that Brahma produced the Brahmanas from his mouth (or the first man Purusha), the Kshatriyas from his hands, the Vaishyas from his thighs, the Shudras from his feet dirty in mud, therefore the essence of nature for the Brahmanas is “holiness and wisdom”, for the Kshatriyas it is “power and strength”, among the Vaishyas - “wealth and profit”, among the Shudras - “service and obedience”. The doctrine of the origin of castes from different parts of the highest being is set forth in one of the hymns of the last, most recent book of the Rig Veda. There are no concepts of caste in the older songs of the Rig Veda. Brahmins attach extreme importance to this hymn, and every true believer Brahmin recites it every morning after bathing. This hymn is the diploma with which the Brahmins legitimized their privileges, their dominion.

Thus, the Indian people were led by their history, their inclinations and customs to fall under the yoke of the caste hierarchy, which turned classes and professions into tribes alien to each other, drowning out all human aspirations, all the inclinations of humanity.

Main characteristics of castes

Each Indian caste has its own characteristics and unique characteristics, rules of existence and behavior.

Brahmins are the highest caste

Brahmins in India are priests and priests in temples. Their position in society has always been considered the highest, even higher than the position of ruler. Currently, representatives of the Brahmin caste are also involved in the spiritual development of the people: they teach various practices, look after temples, and work as teachers.

Brahmins have a lot of prohibitions:

Men are not allowed to work in the fields or do any manual labor, but women can do various household chores.

A representative of the priestly caste can only marry someone like himself, but as an exception, a wedding with a Brahman from another community is allowed.

A Brahmana cannot eat what a person of another caste has prepared; a Brahmana would rather starve than eat forbidden food. But he can feed a representative of absolutely any caste.

Some brahmanas are not allowed to eat meat.

Kshatriyas - warrior caste

Representatives of the Kshatriyas always performed the duties of soldiers, guards and policemen.

Currently, nothing has changed - kshatriyas are engaged in military affairs or go to administrative work. They can marry not only in their own caste: a man can marry a girl from a lower caste, but a woman is prohibited from marrying a man from a lower caste. Kshatriyas can eat animal products, but they also avoid forbidden foods.

Vaishya

Vaishyas have always been the working class: they farmed, raised livestock, and traded.

Now representatives of the Vaishyas are engaged in economic and financial affairs, various trades, and the banking sector. Probably, this caste is the most scrupulous in matters related to food intake: vaishyas, like no one else, monitor the correct preparation of food and will never eat contaminated dishes.

Shudras - the lowest caste

The Shudra caste has always existed in the role of peasants or even slaves: they did the dirtiest and hardest work. Even in our time, this social stratum is the poorest and often lives below the poverty line. Shudras can marry even divorced women.

The Untouchables

The untouchable caste stands out separately: such people are excluded from all social relations. They do the dirtiest work: cleaning streets and toilets, burning dead animals, tanning leather.

Amazingly, representatives of this caste were not even allowed to step on the shadows of representatives of higher classes. And only very recently they were allowed to enter churches and approach people of other classes.

Unique Features of Castes

Having a brahmana in your neighborhood, you can give him a lot of gifts, but you shouldn’t expect anything in return. Brahmins never give gifts: they accept, but do not give.

In terms of land ownership, Shudras can be even more influential than Vaishyas.

Shudras of the lower stratum practically do not use money: they are paid for their work with food and household supplies. It is possible to move to a lower caste, but it is impossible to get a caste of a higher rank.

Castes and modernity

Today, Indian castes have become even more structured, with many different subgroups called jatis.

During the last census of representatives of various castes, there were more than 3 thousand jatis. True, this census took place more than 80 years ago.

Many foreigners consider the caste system to be a relic of the past and believe that the caste system no longer works in modern India. In fact, everything is completely different. Even the Indian government could not come to a consensus regarding this stratification of society. Politicians actively work on dividing society into layers during elections, adding protection of the rights of a particular caste to their election promises.

In modern India, more than 20 percent of the population belongs to the untouchable caste: they have to live in their own separate ghettos or outside the boundaries of the populated area. Such people are not allowed to enter stores, government and medical institutions, or even use public transport.

The untouchable caste has a completely unique subgroup: society’s attitude towards it is quite contradictory. These include homosexuals, transvestites and eunuchs who make their living through prostitution and asking tourists for coins. But what a paradox: the presence of such a person at the holiday is considered a very good sign.

Another amazing podcast of the untouchables is Pariah. These are people completely expelled from society - marginalized. Previously, one could become a pariah even by touching such a person, but now the situation has changed a little: one becomes a pariah either by being born from an intercaste marriage, or from pariah parents.

Indian society is divided into classes called castes. This division occurred many thousands of years ago and continues to this day. Hindus believe that by following the rules established in your caste, in your next life you can be born as a representative of a slightly higher and more respected caste, and occupy a much better position in society.

History of the origin of the caste system

The Indian Vedas tell us that even the ancient Aryan peoples living on the territory of modern India approximately one and a half thousand years BC already had a society divided into classes.

Much later, these social strata began to be called varnas(from the word “color” in Sanskrit - according to the color of the clothes worn). Another version of the name varna is caste, which comes from the Latin word.

Initially, in Ancient India there were 4 castes (varnas):

- brahmanas - priests;

- kshatriyas—warriors;

- vaisya—working people;

- Shudras are laborers and servants.

This division into castes appeared due to different levels of wealth: the rich wanted to be surrounded only by people like themselves, successful people and disdained to communicate with the poorer and uneducated.

Mahatma Gandhi preached the fight against caste inequality. with his biography, he is truly a man with a great soul!

Castes in modern India

Today, Indian castes have become even more structured, with many various subgroups called jatis.

During the last census of representatives of various castes, there were more than 3 thousand jatis. True, this census took place more than 80 years ago.

Many foreigners consider the caste system to be a relic of the past and believe that the caste system no longer works in modern India. In fact, everything is completely different. Even the Indian government could not come to a consensus regarding this stratification of society. Politicians actively work on dividing society into layers during elections, adding protection of the rights of a particular caste to their election promises.

In modern India more than 20 percent of the population belongs to the untouchable caste: They also have to live in their own separate ghettos or outside the boundaries of the populated area. Such people are not allowed to enter stores, government and medical institutions, or even use public transport.

In modern India more than 20 percent of the population belongs to the untouchable caste: They also have to live in their own separate ghettos or outside the boundaries of the populated area. Such people are not allowed to enter stores, government and medical institutions, or even use public transport.

The untouchable caste has a completely unique subgroup: society’s attitude towards it is quite contradictory. This includes homosexuals, transvestites and eunuchs, making a living through prostitution and asking tourists for coins. But what a paradox: the presence of such a person at the holiday is considered a very good sign.

Another amazing untouchable podcast - pariah. These are people completely expelled from society - marginalized. Previously, one could become a pariah even by touching such a person, but now the situation has changed a little: one becomes a pariah either by being born from an intercaste marriage, or from pariah parents.

Conclusion

The caste system originated thousands of years ago, but still continues to live and develop in Indian society.

Varnas (castes) are divided into subcastes - jati. There are 4 varnas and many jatis.

In India there are societies of people who do not belong to any caste. This - expelled people.

The caste system gives people the opportunity to be with their own kind, provides support from fellow humans and clear rules of life and behavior. This is a natural regulation of society, existing in parallel with the laws of India.