Chateaubriand's story "René" as a work of romanticism. Roman F

Literary prototypes: Werther Goethe, lyrical heroes English poets XVIII century Gray and Thomson, the heroes of Ossian's "Poems", the narrator of J.-J. Rousseau's "Walks of a Lonely Dreamer". The story “Rene” was first published as part of Chateaubriand’s treatise “The Genius of Christianity” (1802) as an appendix to the chapter “On the Vagueness of Passions.” In this chapter, Chateaubriand analyzes “a state of mind that has not yet attracted due attention”: “our abilities, young, active, whole, but hidden in themselves, devoid of purpose and subject, turn only to themselves. We experience disappointment without having yet tasted pleasure; we are still full of desires, but already devoid of illusions. The imagination is rich, abundant and wonderful; existence is meager, dry and joyless.

We live with with a full heart in an empty world and, having not been satisfied with anything, are already satiated with everything”; strength “waste in vain”, pointless passions “burn a lonely heart.” Chateaubriand connects this state with the progress of civilization and its sad consequences: “the abundance of examples passing before the eyes, the many books that treat a person and his feelings, make an inexperienced person sophisticated.” The described state of mind also had very specific historical reasons, which Chateaubriand does not name directly, but seems to imply: “ardent souls who live in the world, not trusting it, and become the prey of thousands of chimeras” - these are young people of the post-revolutionary era, from whom the revolution took away not only their relatives, but also their whole life. a familiar way of life, a field in which they could usefully waste their strength.

However, in the story itself, the historical, “material” reasons for Rene’s grief remain behind the scenes, which is why this grief takes on a universal, truly metaphysical character. Overwhelmed by melancholy, Rene leaves his native land and goes on a trip to Europe, visiting Greece, Italy, Scotland; he contemplates ancient ruins and reflects on the fate of the world, sitting on the top of a volcano, and nowhere does his soul find peace. R. returns home, where his beloved sister Amelie is waiting for him, but she is wasting away from an incomprehensible illness and finally retires to a monastery; on the day of her tonsure, R. accidentally recognizes her terrible secret: Amelie has a criminal passion for him, her brother, and that is why he flees from the temptations of the world to the monastery. R., in despair, recognizing himself as the cause of Amelie’s grief, chooses another refuge for himself: he leaves for America, where he settles among the Natchez Indians and marries the Indian woman Selute. Amelie dies in the monastery, but R. is left to live and suffer.

Immediately after release separate publication In the story, Rene's image gained European fame. R. had many successors, from the famous, such as Byron's Childe-Harold, Jean Sbogar Nodier, Aleko, Octave A. de Musset, to unknown complainers, pouring out their sorrows in sad elegies. Chateaubriand himself later, in his autobiographical book “Grave Notes” (ed. 1848-1850), wrote that he would like to destroy Rene or, at least, never create him: too many “relatives in prose and verse” appeared his hero, the writer complained; You won’t find a young man around who isn’t fed up with life and doesn’t imagine himself as an unhappy sufferer. Chateaubriand was upset that his idea was not fully understood, that, captivated by sympathy for Rene, readers lost sight of the ending of the story.

After all, the writer’s goal was not only to portray R.’s disappointment and melancholy, but also to condemn them. In the finale of “Rene,” the hero receives a stern rebuke from the priest Father Suel: a person has no right to be seduced by chimeras, indulge his own pride and languish in loneliness; he is obliged to work together with people and for the benefit of people, and this life, together with his own kind, will cure him of all moral ailments. It is to R. that the Indian Shaktas turns in the finale of the story famous words, which Pushkin loved so much: “Happiness is found only on the beaten path” (cf.: “The habit has been given to us from above; It is a substitute for happiness”). “The beaten path” is a return to people, a cure for universal melancholy. R. himself dreams of such healing; it is not for nothing that he asks the Natchez to accept him as one of the warriors of the tribe and dreams of living the same simple and pure life as they do.

However, Rene is not destined to be cured; and among the Indians he remains a man absolutely disappointed in life, nursing his grief. This attitude towards the world was not invented by Chateaubriand; Not only are there many autobiographical moments in the description of R.’s psychology, it is much more important that many young people experienced similar feelings at the beginning of the century; Chateaubriand only expressed it in such a capacious and comprehensive form that had not been accessible to anyone until then. Many prominent French writers 19th century: Lamartine, Sainte-Beuve, George Sand - recognized themselves and their experiences in R. On the other hand, R.’s story not only expressed an already existing state of mind, but also to some extent provoked it, and itself became a source of total disappointment, because from this story everyone remembered the hero’s melancholy and his absolute rejection of the world around him, but no one wanted to heed Sermons by Father Suel.

Chateaubriand was convinced that he embodied in the image of R. the “disease of the century”, which would die along with the century, but readers of different eras continued to recognize themselves in Rene. According to S. Nodier, the “disease” turned out to be more widespread than the author himself thought. This is an expression of the anxieties of a soul that has experienced everything and feels that everything is slipping away from it, because everything is coming to an end. This is mortal melancholy, insoluble doubt, inconsolable despair of hopeless agony; this is the terrifying cry of a society that is about to disintegrate, the last spasm of a dying world (“On Types in Literature,” 1832). In Russia, special attention to the figure of R. was shown by K.N. Batyushkov (especially sensitive to the ideal of patriarchal life, not knowing self-willed passions, which R. so hopelessly dreamed of) and M.P. Pogodin, who indicated in the preface to his translation “ Rene" (1826) on the similarity of this character with the characters of Wilhelm Meister, the heroes of Byron and Pushkin.

The signs of romanticism as a new poetic system appear even more clearly in the works of Francois-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), and here they grow to a slightly different level. traditional basis, than that of Steel. Chateaubriand, like Stael, owes a lot to sentimentalism, and in his later work classicist features become more active. But Chateaubriand, an aristocrat by birth and conviction, is deeply hostile to the Enlightenment tradition itself and the bourgeois-revolutionary ideology associated with it; he, in fact, from the very beginning firmly chose for himself the role of a zealous defender of the restoration-monarchist principle and the Christian religion.

But last but not least, it was precisely this sharp rejection of post-revolutionary modernity that stimulated Chateaubriand’s work romantic traits. And here we should look for an explanation of the specific contradiction between conservatism political activity Chateaubriand as a publicist and diplomat and the innovation of his artistic aspirations. In both of his guises, Chateaubriand was ultimately inspired by a decisive opposition to the bourgeois age and system; but if in his royalist political programs criticism of the bourgeois century often turned out to be reactionary criticism from the right, then in artistic creativity His, demonstratively distant from the political topic of the day, this anti-bourgeoisism poured out into forms so generalized and spiritual that they turned out to be quite consonant with the romantic ideas of dissatisfaction with the age, “world sorrow”, dual worlds and sublimely abstract symbolic utopianism.

This, in turn, casts a special light on political position Chateaubriand, on his stubborn adherence to the ideals of the past. The fact is that his “positive program” was so romantically maximalist, his dissatisfaction with modernity so comprehensive and absolute, that he ultimately found himself at odds with any particular form government, even if it seemed to correspond to his most cherished ideological ideas. This must be taken into account when it comes to his political and diplomatic activities as a “knight of the Restoration.” Many contemporaries and descendants considered his reclusive sentiments to be hypocrisy precisely on this basis. But, no matter how much panache there is in Chateaubriand’s lamentation, “flirtatiousness with feelings,” “theatricality, pomposity,” according to the well-known definitions of Marx ( Marks K., Engels F. Op. 2nd ed. T. 33. P. 84), the fact remains that he ended up “not at court” every time in the most literal sense of the word: with Napoleon and with the leaders of subsequent monarchical cabinets. It turned out that Chateaubriand’s Christianity and royalism, no matter how zealously they were proclaimed in theory, were of no use to the practitioners of these principles. Chateaubriand the politician was hindered by Chateaubriand the romantic: this is another unique version of the intense contradiction between maximalist utopia and real life, so characteristic of romanticism.

The deep basis of Chateaubriand's retrospective utopia was the Christian religion. In the book “The Genius of Christianity” (1802), in “Grave Notes” (1848-1850) he presented his appeal to religion as a revelation and insight. Meanwhile, the interpretation of the problem of religion in Chateaubriand’s artistic work is very far from presenting to the reader the image of an enlightened, peaceful neophyte. This work, on the contrary, indicates that Chateaubriand’s conversion was the result of deep confusion and lack of rootedness in a hostile world. The history of romanticism knows many examples of atheism out of despair; fight against God is one of the essential elements (more precisely, stages) of this worldview; Chateaubriand apparently demonstrates the opposite option - religious exaltation from despair; but essentially the methodology here is the same - an attempt to try the extreme, unalloyed pure principle; this attempt is maximalist, utopian and therefore fundamentally romantic.

For understanding true meaning For Chateaubriand’s religious utopia, it is important to realize its initial premises, to take a closer look at the “present” image of a person who, in Chateaubriand’s artistic world, has yet to experience the “miracle” of conversion. This is one of Chateaubriand's earliest heroes, Rene in the story of the same name (1802) and in the epic "Natchez", written mainly in the last years of the 18th century, but published in full only in 1826.

Rene is one of the first carriers of the “disease of the century” in European romantic literature, the very melancholy that Chateaubriand theoretically analyzes in the chapter “On the Vagueness of Passions” in the book “The Genius of Christianity.” Strong in image traditional elements: Goethe's Werther is his ancestor in a direct line; in Rene's lamentations about the frailty of all things, echoes of cemetery poetry and Ossianism are clear. But this is already a hero of a new type. On the one hand, the “complex of frailty” in him is far from the elegiac tranquility of the sentimentalists: behind his external detachment from earthly things, a barely concealed pride seethes, a thirst for completely this-worldly recognition and worship, and an internal battle with a hostile society. But, on the other hand, the modern world is not allowed into the very figurative structure of the story; the “unrealizability of desires” as the cause of melancholy is nowhere confirmed by real personal and social experience, as it was in “Werther”, it appears a priori. Both of these features mark deviations from the traditional sentimentalist basis towards romantic “geniocentrism”, for which the external world is conceived as deliberately hostile and worthy of denial entirely, without immersion in details.

But if many romantics began in this situation by soaring to the heights of spirituality and built there, in the “supramundane” spheres, altruistic utopias of future merging, then Chateaubriand’s distance from the world shows a different tendency: it is not in the openness towards “space”, but in radical concentration on the inner life of the individual, in the consistent cutting off of all connections with external being. Thus, in Rene’s story about his European wanderings, we see a dead world dominated by ruins and barren memories - a world that seems to have ended, without a future, without hope. And this corresponds to the endlessly varying images of “isolation” in poetic structure Chateaubriand's prose: the motives of suicide and voluntary confinement in a monastery, which accompany all of his work - from Atal (1801) to The Life of Rene (1844); theme of graves, tombs and burials; Rene’s involuntary, as if organic self-love, which is so clearly expressed in the story of an unhappy marriage with Seluta in “Nachez” and the crown of which appears the specter of incest, isolation even love passion in the sphere of one’s own family and “blood” (Amelie’s theme in “Rene”). The spirit of disappointment and unbelief blows over the writings of this apostle of faith.

It is on this basis of total unbelief that Chateaubriand’s religious utopia arises. That Chateaubriand's religiosity is not so much organic as romantically demonstrative, is revealed especially clearly precisely in the most ardent, initial period of his conversion. In “Atala” and “Rene” - these, in fact, two parables conceived as a demonstration of the “Christian idea” - the contradictions between romantic individualism and Christian dogmatics are glaring. The idea of suppressing passions, proclaimed by Chateaubriand, thanks to the skillful disposition of the plot, is deprived of its absoluteness not only because religious peace is bought at the price of death (Atala) or life ruin (both Atala and Amelie), but also because before the “main” hero Even this ambiguous benefit does not reach: Atala dies - but the suffering Shaktas remains, Amelie gains enlightenment - but the eternally inconsolable Rene remains. Christianity here truly takes on a “diabolic” hue, anticipating the apocryphal Catholicism of Barbey d’Aurevilly and Bernanos.

Chateaubriand's Christianity in this period is thoroughly literary; in the sphere of morality, it is intended to be - after the skepticism and atheism of the Enlightenment and revolutionary eras - as exciting, tickling the nerves as exaggeratedly stormy and exotic pictures of nature are intended to be in the sphere of aesthetics in comparison with the bucolic idyll of sentimentalists.

Of course, she was known to the writer from the very beginning. At the end of “Rene”, Father Suel was already scolding the hero for his immense pride, for moving away from people. But the effect of this morality was not shown - Rene remained on stage, whose very humility was more than pride, and some critics (for example, P. Barberis) even suggested that this sermon could have been added retroactively to the original one, which was more tragic in concept and “ hopeless" complex "Natchezov". In "Martyrs" the dominant theme is ascetic death for an idea perceived as more humane. Because of this, Chateaubriand’s historical-mythological epic also appears to be very modern from an ethical point of view, for “in the era of the crude hedonism of the Directory and the servility of the Empire” it seeks to establish “heroic contempt for personal benefits, the ability to sacrifice life for the sake of beliefs, no matter how chimerical they may be.” "(B. G. Reizov).

The theme of comparison of religions, a constant for Chateaubriand, is also extremely significant in this regard. During the era of work on “Natchez”, “Atala” and “Rene”, exotic interest prevailed in this topic - although already there, along with a programmatic apology for Christianity, the beauty and humanity of “natural” Indian beliefs was affirmed. In “Martyrs,” the Christian religion, of course, rises above the pagan ones, but this is in principle, and in the specific fates of the heroes (Velleda), paganism does not exclude their deep humanity. Finally, in “The History of the Last of the Abencerraches”, various religions, in fact, are already considered as equal and secondary in comparison with such universal principles of morality as spiritual nobility, loyalty and honor. But in it both the features of demonstrative individualistic exaltation and the features of dogmatic religiosity are softened; it increasingly becomes a utopia of purely moral perfection.

Apparently more detached in his artistic works than Steel from the problems " modern man and the world,” Chateaubriand, with all his contradictions, embodies it in his own way, and in this sense, his work is located on the general line of the keen interest of the French romantics in the psychology of the “son of the century.”

E. A. Belskaya

Chateaubriand's epic novel "Martyrs" continues to this day to be one of his least studied works. In Russian science, the only, albeit very significant, study of this novel is the corresponding section of the book by B.G. Reizov "French historical novel in the era of romanticism." French academic criticism gives the novel very contradictory assessments.

Having first been published in 1808, “Martyrs” caused a certain resonance among the reading public. In the difficult historical conditions of that time, the politically tense consciousness of contemporaries saw in the novel many allusions to Napoleon and direct comparisons politicians French Empire with Diocletian's Empire. Developing their guesses, readers often fell into exaggeration and lost their sense of historicism. “What a comparison... I will not abdicate the throne and will not plant lettuce in the Salon,” Napoleon objected to this.

Having seen in “Martyrs” the expression of a new surge of polemics between the writer and the emperor, contemporaries left aside the question of the literary merits and demerits of the epic. Later, abstracting from the allusions and political ambiguities in the novel, Sainte-Beuve defined it as a phenomenon of “pure art”: “When M. de Chateaubriand wanted to withdraw into the sphere of pure art, he wrote the poem “Martyrs”, infinitely distant from society, in which he lived, and completely divorced from the feelings and inclinations of his contemporaries." This work was assessed in the opposite direction by apologists of classicism and ministers of the Catholic Church. The classics criticized the Christian mythology included in the novel, colored by holy miracles, while the church categorically objected to free interpretations of doctrines and history early Christianity. Napoleon’s reaction was also quite confusing: if “The Genius of Christianity” aroused the approval of the first consul, then “Martyrs,” on the contrary, irritated the emperor.

In the emerging concrete historical conditions, when the leading trends of social development were already ensuring the rise of the bourgeois class, Chateaubriand was aware that it was in the sphere of ideology, and above all in religion, which continued to dominate the minds of his contemporaries, that the political interests of the nobility remained most protected. Witnessing a great social upheaval, Chateaubriand, as a convinced monarchist, an aristocrat whose ideals were rooted in the distant knightly past of his class, could not help but regard this revolution as a manifestation of a national tragedy. However, the writer also realized that in modern conditions a literal restoration of the medieval way of life in its original forms is excluded. This feature of Chateaubriand’s social position, on the one hand, allowed for his occasional cooperation with the Napoleon consulate, on the other, it sometimes made him despise the Bourbons who returned from emigration, who, as Alexander I put it, “forgot nothing and learned nothing,” “did not improve and incorrigible." It is known that Chateaubriand, who was in opposition to the royal court of Louis Philippe, refused the pension assigned to him and earned his living as a translator.

Chateaubriand’s direct approach to the Christian theme in the artistic epic was determined by very specific socio-political interests: Christian history, like Christian dogmas, was processed by him in the spirit of compliance with the consciousness of his contemporaries, who had mastered significant cultural experience, including those who had gone through the trials of atheism, Voltairean deism, “ sincere" religiosity of Rousseau, religious doctrinaire of Maximilian Robespierre. “Reaching” the history of the first Christians to modern needs aroused criticism from many outstanding French writers, who did not deny Chateaubriand his talent for processing. Criticizing B. Constant's treatise “On Religion” (1824-1830), Stendhal wrote that he “lacks that inner grace, that spiritual intoxication that distinguishes, for example, the works of M. de Chateaubriand...”, which discovered “the art of touching and give pleasure by expressing lies and the most extravagant absurdities, which he himself, as is easy to see, does not believe at all.”

Religion became in France the basis for struggle with the reigning courts. It is known that by the time in question Napoleon was establishing relations with Catholic Church, declaring his willingness to recognize Catholicism as “the religion of the majority of the French people.” Socially, it was a surrender of the positions won by the people of France during the revolution. This became all the more obvious if we remember that Napoleon was an atheist and “in any case, in the Italian aristocrat Count Chiaramonti, who in 1799 became Pope Pius VII, Napoleon saw not the successor of the Apostle Peter and not the vicar of God on earth, but a nosy old Italian." Napoleon's compromises were determined by big politics: to weaken the possible allies of the Bourbons. Napoleon's religious complaisance increased in light of the tasks of founding the “fourth dynasty,” the Bonaparte dynasty (after the Perovingians, Carolingians and Capetians). However, Napoleon's treatment of Catholic Rome could not but arouse the indignation of the Catholic French, for the emperor showed that the papal blessing was not of decisive importance for him. Napoleon would once again “outdo” the pope in obtaining a divorce from Josephine in 1809. Pope Pius VII and the cardinals around him lay low. This is how the emperor’s relationship with the national religion developed, when Chateaubriand set out to elevate Christianity in the eyes of his contemporaries, to establish the idea of its superiority over other religions and atheism.

After he was twenty-five years old, the writer, according to his own statement, devoted his life to the fight against false ideologies: “...My whole life was a struggle against what seemed to me false in religion, philosophy and politics; against the crimes or errors of my century, against people who abused power to corrupt or enslave peoples,” we read in the preface to “Genius.” Chateaubriand began work on Martyrs in Rome in 1802, a few months after the publication of The Genius of Christianity, which was his creative manifesto. The “Eternal City” with its marble columns of palaces, trailing statues, the baths of Diocletian, the Colosseum seemed to the writer a monument embodied in stone of the dramatic struggle of two world civilizations - ancient and Christian, a monument to the triumph of the latter. In the contemplation of the “new Rome,” which presents to the viewer “the temple of St. Peter and all its masterpieces,” and the ancient one, which contrasts it with “its Pantheon and its scouts,” images were born of how “one leads his consuls and emperors,” and “another summons a long line of his popes from the Vatican.”

In conditions when theological books “are read only by a few pious people who do not need to be convinced,” poets should turn to Christianity: “Martyrs,” in particular, were supposed to demonstrate the cultural and moral-ethical superiority of Christianity over paganism, to show the triumph of Christianity in the process development of civilization. The actual historical and social processes, during which Christianity ideologically prevailed over ancient polytheism and paganism, remained outside the author’s attention. The tasks facing Chateaubriand in the poem (he himself called the novel a poem) seemed to him quite achievable even without showing the reasons for the social movement of the lower classes, the crisis of the politics of imperial Rome, the movement of the barbarians and the formation of a new feudal reality.

The writer focuses on certain aspects of the moral and dramatic confrontation between polytheism and Christianity, i.e. on those aspects that remained relevant until modern times. Apparently, the focus on modernity predetermined historical anachronism in the description of historical characters: “Almost all the greatest figures of the church lived between the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 4th century. And in order to introduce all these wonderful people to the reader’s eyes, I had to compress the time somewhat.”

Historical characters The early Christian movement and imperial Rome do not determine the plot action, do not resolve the conflict that has arisen, although they are in a certain relationship to it. They are only occasionally mentioned. This author's attitude follows from the ideological intention to provide excellent examples of early Christian martyrdom. The contradiction between Christian and ancient, pagan cultures turns out to be reduced to a confrontation between internal tendencies in spiritual consciousness Eudora. In the novel, the disintegration of the epic and historical materials included in it, but not “girdled” by the line of Eudora, is obvious. Excellent cultural material, city landscapes, historical sketches were frozen into historical scenery and were not included in life circumstances central characters. There is no need to deny B. G. Reizov’s idea that “Martyrs” is the first example of “local color” in French literature.

But the novel also testifies to the fundamental methodological imperfection in historical reconstruction. Analyzing the principles of the historical reconstruction of reality in Chateaubriand, it should be noted that the writer does not recreate the atmosphere of simplicity and fraternal solidarity that reigned in the early Christian community, which had a real social basis. The transition to Christianity of Empress Prisca and her daughter Valeria, which is an episode of an epic branch of the plot in the novel, is considered by the author in an abstract moral aspect; it is rather an occasion for a panegyric to Christianity: “O kingdom of religion, which enticed the wife of the Roman emperor to secretly leave the imperial bed like an unfaithful woman “to run towards the unfortunate, to go look for Jesus Christ at the altar of the unknown martyrs, among the tombs, surrounded by people persecuted and persecuted.” Such a comment, naturally, does not clarify the nature of the appeal of representatives of the imperial court, members of Diocletian’s family.

In fact, this plot motif of the novel opened up for Chateaubriand the possibility of a deeply historical analysis of the conflict, large-scale in content and significance, of the border collision of the ideological systems of two worlds. The conversion of Prisca and Valeria to Christianity became real in the context of the exhaustion of the ancient worldview. Imperial Rome, although it retained its splendor and power, was entering a period of economic and political crises which ultimately led to his downfall.

Disease processes have taken over all areas of life. People of different social origin the world began to seem like a concentration of evil and injustice. Mass consciousness I became more and more interested in belief in witchcraft, magic, and soothsayers. There was a need to combine the religious-mystical and philosophical interpretation of reality, which was uniquely refracted in Christianity. However, the mass, democratic aspect in the novel, reflecting the victory of Christianity over polytheism and atheism, was absent, although the novel was initially conceived as an epic in the spirit of the Christian epics of Dante, Milton, Tasso, Essian.

The writer worked on the epic until 1809. Colossal historical and factual material was collected. In the novel structure of “Martyrs”, in the abyss of historical, cultural, aesthetic and Christianological materials, there lived an independent plot about individual human destinies and above all the two lovers Eudorus and Kimodocia. In writing their names we follow the tradition of B. G. Reizov.

Typologically, such a structure is not contraindicated for the epic genre: but the events of the world background and the individual destinies of the characters turned out to be difficult to connect. The aesthetics of epic poems requires that individual epic action proceed from the foundations of existence; it directly enters into the lives of the characters, their intentions, and goals. The grandiose material, together with the line of individual destinies, adds up “to the overall picture of a given century and national characteristics.” However, Boileau’s aesthetics already connected the genres of epic mainly with the structural features of epic poems, the material of which should be majestic events unfolding on mythological basis. These rights turned out to be quite feasible for Chateaubriand, who announced in “Genius” the need to create a new, Christian mythology.

Broad life and Christianity are presented in the novel as the two main dominants of possible development central characters- Christian martyrs. The depiction of the process of formation of true Christians gives grounds to talk about a unique version of the Christian novel of education, plot basis which is formed by stringing together dramatic scenes from the life history of Kimodocia and Eudor. Drama naturally flowed from the very nature of the characters depicted, from the process of re-educating them as worldly people, whose faith increasingly united them with God. It was in the creation of a new type of ideal character (holistic, harmonious, balanced) that Chateaubriand saw the aesthetic merit of Christianity, in moral basis Of this nature, Christianity, by revealing the true God, reveals the true man.

The ideality of the characters of the main characters, their moral stoicism, persistent and consistent development during the plot action of the main idea associated with the affirmation of the greatness of Christianity, its significance for modern civilization, forced the writer himself to talk about “Martyrs” as an epic poem. Indeed, Chateaubriand, in the images of Eudorus and Kimodocia, reflected the complex process of the formation of truly heroic and tragic characters (of course, not without pauses, but the latter emphasized the strength of the moral principles of Christianity to a greater extent than the real contradictions during the conversion of the heroes). In the spirit of the religiosity of literature, the main characters live the circle of existence, repeating, as Hegel accurately noted, the eternal history of God: being subjected to endless hardships, cruel persecution, showing greatness in their readiness to endure them.

At one time, Hegel also warned about the dangers lurking in the passion for describing unheard-of horrors, corporal punishment and torture, beheading, burning, wheeling, etc., believing that the inclusion of such materials would destroy the aesthetic content of art. However, in relation to the history of Rome during the time of Diocletian, this aspect of the depiction of historical reality seems to be quite justified in terms of content, since it is a means of recreating historical flavor. “In the 3rd century. imperial Rome, saturated with bloody unrest, is entering a difficult period of slow decline, which ends with its immersion in the world of emerging feudalism, slowly rising onto the stage of history” - this is a general characteristic of Rome during the times of Diocletian, his successor Hercules, Galerius, during whose reign the persecution of Christians began , Eudora and Kimodokia in particular.

The drama of what is happening predetermines the uniqueness of the event being recreated. Contrast becomes the leading principle in depicting characters, the appearance of heroes, their speeches and behavior. On the one hand, old Diocletian, Constantine on a horse, Galerius in a magnificent carriage on a pair of tigers, on the other, Eudorus. “And behind everyone walked one, with a stern look and downcast eyes, Evdor, he was wearing a simple black dress" The image takes on a scenic character: the writer pays great attention to the arrangement of figures, description of their poses and gestures. For example, a description of the pose of Hercules: “Hercules stood up. He was wearing a raincoat. His face was stern and thoughtful. He stood silently for some time so that they would pay attention to him, and suddenly he quickly extended his hands, threw back his cloak and, pressing his hands to his heart, bowed to the ground to Diocletian and Galerius and began to speak.”

Chateaubriand managed to convey in the novel the real-historical inconsistency of the attitude of ruling Rome towards Christianity: Diocletian’s personal tolerance towards Christians, the fierce hatred of Hercules (Herculius).

Through Eudora, Chateaubriand gives Christianity the opportunity to express its doctrines and claims to be the only state religion: “They say that the Christian faith came out to the rabble and that is why it contains these abominations. But you reproach her for what constitutes her beauty and glory. She came to console people about whom people had forgotten and from whom they had turned away... Our faith did not accept anything bad from the people, but it corrected their morals...” And further: “Rome rises and asks for Christ.”

This scene in the novel is associated with the completion of the plot action: Eudor, following the denunciation of a slave, was captured and imprisoned; The wanderings of his wife Kimodocia also end tragically, who suffers three times: both as a persecuted Christian, and as the wife of Eudora, and as a woman persecuted by the male claims of Hercules. The fate of Kimodocia is a chain of continuous persecution and suffering: because of her love for Eudor, she accepts Christianity, although she endlessly loves her father Demodocus, who is a pagan priest; having saved his daughter from the persecution of Hercules, Demodocus had previously dedicated her to the priestess of the goddess of the muses; love for Eudor required Kimodocia to renounce her former faith, and conversion to the Christian faith plunged her into new torments and endless wanderings. The heroine witnesses a fire in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem; fleeing from the slaves of Hercules, she goes by ship to Greece; however, a storm brings him to Italy, where her husband is imprisoned, all Christians are thrown to the beasts in the circus, and they decide to send her to an “indecent house.”

It is noteworthy that the line of Kimodokia’s upbringing is steadily developing upward, her behavior, her choice in exceptionally dramatic conditions is invariably associated with the triumph of faith. Hercules could not achieve her love at the cost of Eudorus' life; she renounces freedom, suffering for her father, who is seeking her release, and shares the fate of her husband and condemned Christians. Eudorus also faces a choice of this kind, who is called upon to apostatize from God at the cost of saving Kimodocia. The epic ends, however, according to the principles dramatic action, which was fully consistent with the principles of Aristotelian poetics. The death of the main plot characters - Eudora and Kimodocia - in the Roman circus became a symbol of the triumph of Christianity.

The completion of the heroic life of the characters occurs again according to the principles of classicism aesthetics. The images of Eudora and Kimodokia formally and meaningfully reflect the coincidence of reality and concept. Hegel characterized the ideal of classical art: “The uniqueness of the content in classical art lies in the fact that it itself is a concrete idea and, as such, a concrete spiritual principle.” Calmness is the hallmark of this type of ideal, so when describing it, Chateaubriand resorts to the principles of sculpture and painting. The private, individual, personal is suppressed, all the strength, will, passion of Evdora before execution was melted into higher principles his life: “Eudor stood in front of the girl, folding his hands and raising his eyes to the sky,” Kimodocia “died without suffering.”

As in a drama, other characters in the novel also complete their lives, reflecting the completion of the conflict; Diocletian; Galerius’s triumph did not last long - Constantine, having defeated his troops near Rome, became emperor and allowed Christians free religion; Hercules was overthrown by the people and, seriously ill with leprosy, was treated by Christians. Thus, the final individual action - the line of education of the main characters - becomes the completion of the epic narrative. This again corresponds more to the canons of drama than epic, and the depicted heroes are presented more like characters from medieval, knightly epics than heroic ones: the same abstractness of ideal characteristics, alienation from the national content, “substantial in the proper sense of the word” (Hegel), insufficient vitality completeness, one-sidedness of pathos, predominance “behind one passion and its reasons.”

The author's pathos also determined the nature of the depiction of circumstances in the novel: moral purity family life, fraternal mutual assistance, the Christian charity of the simple warrior Zacharias, the majestic simplicity of Bishop Cyril and the ability for forgiveness of Bishop Marcellinus, as well as the Christian love of Eudorus and Kimodocia, are contrasted with imperial Rome, whose polytheism turned into atheism. Recreating in a novel christian world through the description of the destinies of Eudorus and Kimodocia, it was necessary to reflect not only his opposition to imperial Rome, but also the possibility of the transition from the polytheistic state of humanity to Christian religiosity. In “Martyrs” there is no such detailed opposition of the emerging civilization to the ancient, Homeric era and Homeric aesthetic culture, although the novel contains many descriptions of religious ceremonies, holidays, and cult rituals (the holidays of Diana, Bacchus, etc.). In the preface to Martyrs, the writer explained his plan: “I was looking for a possible historical era of contact between two religions.”

Keywords: François René de Chateaubriand, François-René de Chateaubriand, epic novel, aesthetic concept, Martyrs, romanticism, criticism of Chateaubriand's work, criticism of Chateaubriand's works, download criticism, download for free, French literature of the 19th century

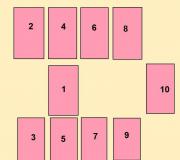

Rene, a young man of a noble family, settles in a French colony in the wilds of Louisiana, among the Natchez Indian tribe. His past is shrouded in mystery. Rene's tendency towards melancholy makes him avoid human society. The only exceptions are his adoptive father, the blind elder Shaktas, and the missionary of Fort Rosalie, Father Suel. In vain, however, they try to find out from Rene the reasons for his voluntary flight. For several years, Rene has been hiding his secret. When, having received a certain letter, he began to avoid both of his old friends, they convinced him to open his soul to them.

On the banks of the Mississippi, Rene finally decides to begin his story. “How pitiful my eternal worry will seem to you!” - says Rene to Father Suel and Chactas, “a young man devoid of strength and valor, finding his suffering in himself” and complaining only about the troubles that he caused to himself.

His birth cost his mother's life. He was brought up far from his parents' shelter and early on showed an ardent nature and uneven character. Rene feels free only in the company of his sister Amelie, with whom he is bound by close and tender ties of similarity of characters and tastes. They are also united by a certain sadness lurking in the depths of the heart, a property bestowed by God.

Rene's father dies in his arms, and the young man, feeling the breath of death for the first time, thinks about the immortality of the soul. Deceptive roads of life open before Rene, but he cannot choose any of them. He is tempted to hide from the world, reflecting on the bliss of monastic life. The eternally anxious inhabitants of Europe erect for themselves abodes of silence. The more confusion and bustle there is in human heart, the more they attract solitude and peace. But due to his characteristic inconstancy, Rene changes his intention and goes on a journey.

At first he visits the lands of disappeared peoples, Greece and Rome, but soon he gets tired of “rummaging in the graves” and discovering “the ashes” criminal people and business." He wants to know whether living peoples have more virtue and less misfortune. Rene especially tries to get to know people of art and those divine chosen ones who glorify the gods and the happiness of peoples, honor laws and faith. But modernity does not show him beauty just as antiquity does not reveal truth.

Soon Rene returns to his homeland. Once upon a time in early childhood he had a chance to see the sunset of a great century. Now he has passed. Never before has a change so surprising and sudden happened to any people: “the loftiness of the spirit, respect for faith, strictness of morals were replaced by resourcefulness of the mind, unbelief and depravity.” Soon, in his homeland, Rene feels even more alone than in other countries.

He is also upset by the inexplicable behavior of his sister Amelie, who left Paris a few days before his arrival. Rene decides to settle in the suburbs and live in complete obscurity.

At first, he enjoys the existence of a person unknown to anyone and independent of anyone. He likes to mingle with the crowd - a vast human desert. But in the end it all becomes unbearable for him. He decides to retire to the bosom of nature and end his life’s journey there.

Rene is aware that he is blamed for his fickle tastes, accused of constantly rushing past the goal he could achieve. Possessed by blind desire, he seeks some unknown good, and everything completed has no value in his eyes. Both complete loneliness and incessant contemplation of nature lead Rene to an indescribable state. He suffers from an excess of vitality and cannot fill the bottomless emptiness of his existence. Either he experiences a state of peace, or he is in confusion. Neither friendships, nor communication with the world, nor solitude - nothing Rene succeeded in, everything turned out to be fatal. The feeling of disgust for life returns with renewed vigor. Monstrous boredom, like a strange ulcer, undermines Rene’s soul, and he decides to die.

However, it is necessary to dispose of his property, and Rene writes a letter to his sister. Amelie feels the coercion of the tone of this letter and soon comes to him instead of answering. Amelie is the only creature in the world that Rene loves. Nature endowed Amelie with divine meekness, a captivating and dreamy mind, feminine shyness, angelic purity and harmony of soul. The meeting of brother and sister brings them immense joy.

After some time, however, Rene notices that Amelie begins to lose sleep and health, and often sheds tears. One day, Rene finds a letter addressed to him, from which it follows that Amelie decides to leave her brother forever and retire to a monastery. In this hasty escape, Rene suspects some secret, perhaps passionate love, which the sister does not dare admit. He makes one last attempt to bring his sister back and comes to B., to the monastery. Refusing to accept Rene, Amelie allows him to be present in the church during the ceremony of her tonsure as a nun. Rene is amazed by his sister's cold firmness. He is in despair, but is forced to submit. Religion triumphs. Cut off by the sacred rod, Amelie's hair falls. But in order to die for the world, she must go through the grave. Rene kneels before the marble slab on which Amelie is lying, and suddenly hears her strange words: “Good God<…>bless with all your gifts my brother, who did not share my criminal passion!” This is the terrible truth that Rene finally reveals. His mind is clouded. The ceremony is interrupted.

Rene experiences deep suffering: he became the unwitting cause of his sister’s misfortune. Grief is now a permanent state for him. He makes a new decision: to leave Europe. Rene is waiting for the fleet to sail to America. He often wanders around the monastery where Amelie took refuge. In a letter he received before leaving, she admits that time is already softening her suffering.

This is where Rene's story ends. Sobbing, he hands Father Suel a letter from the abbess of the monastery with the news of the death of Amelie, who contracted a dangerous disease while she was caring for other nuns. Chactas consoles Rene. Father Suel, on the contrary, gives him a stern rebuke: Rene does not deserve pity, his sorrow, in in every sense words are nothing. “You cannot consider yourself a person of exalted soul just because the world seems hateful to you.” Anyone who has been given strength is obliged to devote it to serving his neighbor. Shaktas is convinced that happiness can only be found on paths common to all people.

A short time later, Rene dies along with Chactas and Father Suel during the beating of the French and the Natchez in Louisiana.

Philosophical materialism of the eighteenth century reached its highest practical application in the atheistic antics of the great French Revolution. Therefore, it was quite natural that after the end of the revolution there was a desire to reawaken religious feelings among the people and to heal through Christianity the wounds inflicted by the philosophy at war with the church. Already Madame de Stael pointed out the need religious revival and, during the consulate, exchanged thoughts with the founder of Christian romance in France, Viscount Chateaubriand. Napoleon Bonaparte and his brothers and sisters supported this literary movement, which contributed to the restoration of order in public and state life.

Francois-René de Chateaubriand. Portrait by A. L. Girodet

The beginning of Chateaubriand's creativity

François-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848) was born in Brittany into a noble family attached to ancient beliefs and superstitions, and grew up in a not very rich home environment. His proud father gave him a harsh upbringing, which forced him to become secretive; his pious mother and exalted beloved sister spoiled him; Therefore, Chateaubriand early began to live by imagination, which overly excited his mental and physical powers - he began to love solitude, fell into melancholy, shunned people, began to indulge in dreams of love, the object of which were ghostly creatures, and in this painful state of mind began to think about suicide .

Like many other nobles of Brittany, François-René Chateaubriand went to America as soon as the revolution broke out. The horrors of the revolution outraged his tender heart. Chateaubriand retired across the Atlantic Ocean, and after his return to Europe he joined the emigrants living in London. Tormented by worries and doubts, he listened to the dying admonitions of his mother, who died in extreme need, and believed in what his ancestors believed. Returning to France, after the coup of the 18th Brumaire, together with Fontaine (1757-1821), that skillful rhetorician and orator of the convention (“Washington’s Panegyric”), he began to take part in the publication of the very widespread magazine “Mercure de France”. Influenced by the impressions gained from reading the works of Rousseau and Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Chateaubriand described the religious contemplation of nature in two stories “Atala” and “Rene”, and his great work “The Spirit of Christianity”, so rich in poetic ideas, aroused such warm praise that he was showered with honors and favors. Chateaubriand soon became the soul of circles of gifted people who gathered with Fontagne, who extolled Napoleon's rule with pompous speeches in the Senate and in the legislative body, with the critic and aesthetician Joubert (Recueil de pensées), with Portalis, an experienced lawyer who helped Napoleon in drawing up the code and in concluding Concordat, and from some ladies, especially Madame Recamier.

Chateaubriand's stories "Atala" and "Rene"

While still living in America, René Chateaubriand drew up a plan for a great heroic poem, in which he intended to portray man as the son of nature, as opposed to civilized man. The content was supposed to be the tragic fate of the Natchez tribe in Louisiana, where in 1729 both local natives and French colonists died. According to his assumption, "Atala" and "Rene" were supposed to constitute fragments or episodes of the great heroic poem about the Natchez. Those ideas about the religious contemplation of nature, which gave Chateaubriand’s first works a special attractiveness, developed in the mind of the author among the French colonists, who still preserved the old customs in America, folk songs, forms of language and religious ideas of the sixteenth century, and among the savages who lived in the forests and on the steppes. Sincerity and novelty in the description of nature and feelings are what gave Chateaubriand’s novels “Atala” and “Rene” special value and attractiveness in the eyes of the French people and all those who wanted to warm their hearts with religion and Christian feelings. In their originality, in their mixture of Christian feelings with descriptions of wild nature, these works seemed like saving oases in the midst of a literary desert.

Chateaubriand – “The Genius of Christianity”

Both the novel "Atala", in which Chateaubriand described the customs and way of life of one of the North American tribes, among whom he lived for two years, and the similar novel "Rene" soon reached the widest distribution even before they were attached in the form of episodes to the main work “The Genius of Christianity” (Génie du Christianisme), which Chateaubriand wrote during Napoleon’s negotiations with the Pope about the Concordat, in the country house of his friend and admirer, Madame Beaumont. This famous work, which completely transfers Christian ideas into the realm of the elegant and makes religion an object of aesthetic pleasure, depicts in stories, in paintings and in pious dreams the poetic religion of Chateaubriand and his Catholic philosophy. “The genius of Christianity” became a sacred scripture for those salon gentlemen and ladies to whom the biblical religion seemed too ungraceful and dry. This work by Chateaubriand became a poetic justification of those Christian legends and mysteries, those sacred legends and tales that were intended for people with elegant taste and developed imagination. The brilliant style, the description of landscapes, the soft tone of the picturesque poetic prose and the perfection of presentation evoked no less ardent praise than the Christian content. But for Chateaubriand, the prevailing mood of mind at that time turned out to be especially beneficial, since as a result of the conclusion of the concordat, “all pious people were confident in the salvation of their souls, and even sensible people, not without joyful emotional excitement, returned to unforgettable religious feelings and customs.”

Brief summary of Chateaubriand's works

The daughter of the steppes Atala, Chaktas and Father Aubry, whose hands were cut off by the Indians long ago and who is trying to instill sentimental Christian feelings in the two lovers in order to give them consolation in earthly hardships - these are the main characters of Chateaubriand’s novel “The Genius of Christianity”, who amazed with their originality in such a time. time when concordat founded a new papist-Bonapartist church in France to replace the old Gallican-Bourbon one. Thus, this novelty appeared both in real life and in the novel under old forms. In René, Chateaubriand portrayed both his own personality and the demon of his time with a terrifying, but at the same time fascinating fidelity. "René" has been compared to Goethe's Werther; both of them are grief-stricken people and the first types of that painful sensitivity that young poets loved to describe under the name of world grief. In Chateaubriand's description, Rene's heart is filled with a wild, gloomy ardor that only devours it and does not warm it. There is no faith or hope in this heart; it is not able to drown out in itself that demonic desire to destroy everything, which makes the hero Chateaubriand think that his life is just as empty as his soul. Wandering melancholy as a homeless wanderer, Rene feels deep heartfelt sorrow. His sister Amelia has a passionate love for her brother and seeks in the monastery peace of mind and oblivion. He leaves for America, joins the army of an Indian tribe, marries an Indian girl, Celuta, and takes part in hunting expeditions and in the Natchez wars, as told in the novel of that name. He dies while this tribe was exterminated. Before his death, he learned about the death of his sister in the monastery and expressed his feelings and his desperate grief in a letter to Celuta, which Chateaubriand recalled with pride even in his old age. This novel is an epic written Ossianovskaya prose.

Both stories, “Atala” and “Rene,” presented by Chateaubriand in the form of autobiographies, are remarkable for their poetic descriptions of nature and an abundance of apt characteristics and comparisons. In “The Genius of Christianity,” Chateaubriand extols the essence of the Christian religion, the pomp of worship, symbolism, ceremonies and legends of the medieval church, and in support of these fantastic dreams, replacing scholastic church teaching, he constantly calls on the feelings and imagination to his aid. In the same spirit as “The Genius of Christianity”, Chateaubriand wrote a short novel, the content of which dates back to the times of the rule of the Moors in Grenada - “The Adventures of the Last Abenceragh”; this elegy about vanished chivalry represents a harmonious piece of art, which spoke to both the imagination and the heart and contributed greatly to the revival of romanticism.

Creative style of Chateaubriand

“In all the works of René Chateaubriand,” says Schlosser, “we find well-chosen pictures and expressions, freshness, originality and poetic inspiration; but we should not expect that the views expressed by the author can withstand calm, sensible criticism or that they, at least, agree with one another; the expectation of harmonious wholeness would be even more vain. As soon as he ceases to expound small ideas and moves on to larger views, we cannot rely on his arguments. We would look in vain to Chateaubriand for a calm verification of the results of his observations; on the contrary, we everywhere find in him the flavor of an experienced and inventive painter. His style is often distinguished by its loftiness, but in some places it falls very low. This most often happens when Chateaubriand goes too far in his efforts to imitate ancient writers and as a result loses the ardor of his feelings. And with all his efforts to imitate the tastes of noble society, he reveals a certain independence, which he retained under the influence of the impressions he gained from visiting the wild countries of America in his youth.”

Chateaubriand's life after his break with Napoleon

After assassination of the Duke of Enghien Chateaubriand did not want to be a servant of the Napoleonic dynasty. He refused the diplomatic posts entrusted to him by the emperor in Rome and Switzerland and, deeply upset by the death of his sister Lucille, who served as the prototype for Amelia in the novel Rene, undertook big Adventure to Greece, Egypt, Jerusalem and on the way back stopped in Spain (1806). The fruit of this journey should be considered not only "Itinéraire" ("Itineraire", "Travel Diary"), but also the poem "Martyrs", in which Chateaubriand tried to explain the superiority of Christianity over Greek paganism with the help of brilliant sketches, but also with the help of erroneous exaggerations and biased judgments. In the story of his pious journey to Jerusalem, Chateaubriand correctly and attractively described the impressions and religious feelings of the poet at the sight of the Holy Places and eastern nature, sanctified by great historical memories.

Chateaubriand reflects on the ruins of Rome. Artist A. L. Girodet. After 1808

The religious and political views of René Chateaubriand became dominant during the restoration: then a golden age began for the poet. But even in those critical days, when the Bourbon restoration had not yet been consolidated, Chateaubriand’s essay “On Bonaparte and the Bourbons,” despite the fact that it was filled with abusive and exaggerated accusations of Napoleon, had such a strong influence on the mood of minds in France that what's in the eyes LouisXVIII cost an entire army. Then Chateaubriand at one time held the position of minister, was an envoy to several European courts, participated in the Congress of Verona, and in several political writings defended the principle of a legitimate monarchy; however, his changeable, elastic nature more than once pushed him to the side of the opposition. This ultra-royalist, who approved of the conclusion of the Holy Alliance, at times shared the beliefs of the liberals.

As an adherent and champion of legitimism, Chateaubriand, after the July Revolution of 1830, renounced the title of peerage and began to defend in his pamphlets the rights of the senior line of Bourbons, showering him with harsh abuse and Louis Philippe and his followers, until the pitiful fate which befell the Duchess of Berry at the Vendée weakened his romantic royalism. His “Grave Notes” (Mémoires d`outre tombe) reveal the influence of old age with their chatty self-praise. Reading them, you come to the conviction that Chateaubriand repeatedly changed his views, in accordance with the circumstances and with the prevailing opinions at the moment, that his inspiration was often more artificial than sincere and truthful. He constantly moved from poetic dreams to real life, which had nothing in common with those dreams.

Chateaubriand contributed French literature a new element that soon received widespread development - romanticism and the poetry of Catholic Christianity. It cannot be said that French writers began to consciously imitate German ones in this regard, but the aspirations that prevailed in that “era of reaction” led writers of both countries to the same paths and views. Since then in France romanticism began to play a significant role in poetic works, although he did not dominate others literary trends just as certainly as in Germany. Chateaubriand's influence greatly contributed to this.