History of the district. Strange poplar near the apple orchard on Kolomenskoye Prospect

The recent third wave of reposts prompted the idea of continuing the theme banquet.

Moreover, the seventies are relatively not so far away and many people remember them.

So, let's walk along the outskirts of Moscow, making a full circle clockwise.

Brateevskie fields. The photo is captioned: “seeing off to retirement.”

There are fields here even now, but you won’t see such colorful characters anymore.

In the distance is Kapotnya with its breathtaking industrial zone.

Photo: N.A. Stepanov.

02.

Village of Dyakovo, wedding. The composition of the orchestra is impressive. This is not the Pronkins’ name day!

Photo from the archive of Alexander Kachalin.

03.

Neighboring Kolomenskoye. Vegetable gardens against the backdrop of famous architectural monuments.

04.

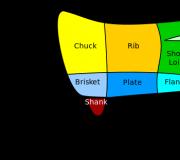

Another perspective. Real fields. In those days, there was still a collective farm operating here with the shocking name “Garden Giant”.

Photo: G.A. Mironov

05.

A good-quality hut in the village of Kolomenskoye.

Behind are the new buildings of that part of Proletarsky Avenue that has not yet become Andropov Avenue.

06.

At the once dacha platform "Tsaritsyno". View towards the park. On the right is a discount store, yeah.

Photo from the archive of Dmitry Abramov.

07.

Street in the village of Tsaritsyno. A young family came to visit their mother/grandmother.

Photo from the archive of Alexey Smetankin.

08.

The city is coming... Profsoyuznaya Street. There is no metro station "Belyaevo" yet. There is still a lot missing.

On the left, a working cowshed entered the frame.

Photo from the archive of Alexey a.k.a. Lexx

09.

What an idyll! This is Yasenevo, view of the Church of Peter and Paul. Massive construction is about to begin.

10.

Bogorodskoe. Where dogs are walked now, it was then customary to walk a cow.

The photo was taken in a half-filled ravine of the Ochakovka River.

New buildings of the Second Moscow are being built behind medical institute(on Ostrovityanova Street).

Photo from the archive of Fedor a.k.a. Theo.

11.

The last huts of Bogorodsky against the backdrop of 123 building 1 on Leninsky Prospekt.

Photo: E.A. Kulakov.

12.

And here is a textbook place. The Temple of the Archangel Michael, which starred in the film, the first words from which I quote here:

“Villages near Moscow: Troparevo, Chertanovo, Medvedkovo, Belyaevo-Bogorodskoye, and of course, Cheryomushki did not suspect that they were gaining immortality in those sad days for them, when they were forever swept away from the face of the earth.”

Here the village of Troparevo has not yet been swept away.

Photo: Valentin Polyakov.

13.

Hay hauler and hay cart. Street of 26 Baku Commissars. In the background, a Tourist House is being built.

Photo: Valentin Polyakov.

14.

...Now - with the owner. Photo by the same author, on the same street, but in the opposite direction.

15.

Village Nikulino. The bus goes along the now non-existent section of Borovskoye Highway towards the city.

Photo - again Valentin Polyakov.

16.

House for two families in the village of Ramenki. Long demolished, of course.

But both poplars near the fence and the pear tree that stood behind the porch have been preserved: https://maps.yandex.ru/-/CVHUqPO7

Photo from the archive of Dmitry Gulyutin.

17.

Matveevskoe. A private (well, what else?) cellar near the railway against the backdrop of new buildings in the area.

Photo from the archive of Natalia Zlobina.

18.

Native spaces... the Setun valley between Davydkov and Matveevsky. Fields and vegetable gardens. Now everything is pretty overgrown.

19.

Krylatskoe, before Easter. In the background is the Grebnoy Canal. Rowing, not mushroom and not cesspool!

Photo from the archive of Yu.P. Lyzlov.

20.

Landscape with a column. Trinity-Lykovo. In general, the rural character of the area is still preserved there.

Photo: S.N. Volkov.

21.

Also Trinity-Lykovo, from the same author.

“Milk and hay,” said Ostap, when “Antelope” left the village at dawn, “what could be better! You always think: “I’ll still have time for that. There will be a lot of milk and hay in my life.” But in fact, never this won't happen anymore."

At least for the former Moscow villages, this decadent statement is true.

22.

Picnic in Skhodnensky Kovsh. Behind the vacationers are hang gliding enthusiasts. I remember, I remember, we flew.

Photo: Victor Zagumennov.

23.

View of the village of Lianozovo from an airplane.

Perhaps modern residents of Khotkovskaya and Novgorodskaya streets will be curious to see the place where their high-rise buildings now stand like this.

Photo from the family archive of Alexey a.k.a. Sch.aa.

24.

Yard in the village of Vladykino.

Photo from zahar's archive.

25.

The beautiful Church of the Intercession in Medvedkovo. Below is Yauza.

Photo: A.A.Alexandrov.

26.

View from the bus window at house 135 on Yaroslavskoye Highway.

Photo: James S. Olsavsky (well done foreigner: otherwise the majority, like donkeys, photographed Red Square and Moscow State University, as if there was no one to do it without them!)

27.

Iiiiahhaaaa! Cheerful family in Losiny Ostrov.

By the way, my hat was exactly the same.

Photo: Vitaly Tyunin.

28.

At the Church of Elijah the Prophet in Cherkizovo. Well, it’s like Levitan’s March, only in black and white.

Photo from the archive of Elena Shcherbakova.

29.

Izmailovo. In the garden. Style - realism.

30.

Izmailovo state farm for ornamental gardening (which is behind 16th Parkovaya). Apparently, high school students-interns.

31.

The poor lands of the Belaya Dacha state farm, somewhere in the area of the street with the characteristic name Verkhnie Polya.

Photo: V.N. Drobinin.

Well, the circular review is over. We started at the Moscow River and ended not far from it. I hope it wasn't boring.

All pictures taken from the site

The Nagatinsky Zaton district is located in the south of Moscow, on the right bank of the Moscow River, surrounded on three sides like a peninsula by the Moscow River. The border of the district runs along the northern borders of the territory of the Kolomenskoye Museum-Reserve, then along Andropov Avenue, the old bed of the Moscow River, lock 10-11 of the Moscow River to the Kolomenskoye Museum-Reserve.

The Nagatinsky Zaton area has a rich historical past. Where the modern building blocks are now located, in the past there were located well-known villages near Moscow in the history of the Russian state: Kolomenskoye, Nagatino, Novinki.

The area adjacent to the village of Kolomenskoye has long been inhabited. The high hilly bank of the Moscow River was a convenient place for human settlements. The Dyakovo settlement existed here at the dawn of our era.

Archaeological excavations have shown that the first settlement on the territory of Moscow appeared here two and a half thousand years ago. primitive people, now known to all archaeologists in the world. The oldest Neolithic settlements of people dating back to the 1st millennium BC were discovered. - IV century AD, which gave the name to the entire culture of this period - “Dyakovo culture” (archaeological culture of the early Iron Age). The basis of the economy of the tribes of the Dyakovo culture is agriculture, sedentary cattle breeding, fishing, and hunting.

The village of Kolomenskoye is located in an area of rare beauty, which is also interesting geologically. INIn the ravines of Kolomenskoye you can still observe the remains of continental glaciation - huge sandstone boulders “Goose” and “Maiden Stone”, which had ritual significance for pagan tribes.

About the time of the emergence of two ancient villages near Moscow, Kolomenskoye and Nagatinskoye documents. et. The first written mentions of them are found in spiritual documents of 1336 and 1339. Prince Ivan Kalita, collector of Russian lands around Moscow.

et. The first written mentions of them are found in spiritual documents of 1336 and 1339. Prince Ivan Kalita, collector of Russian lands around Moscow.

The name of the village of Kolomenskoye, according to one version, comes from the inhabitants of Kolomna who settled here in the 13th century, fleeing from the invasion of Batu, according to another - from the many hills and mounds that covered this area and were called “Kolomishi” in ancient times.

Located at the intersection of the most important water and land roads to the capital, Kashirskaya and Serpukhovskaya, fenced from the north by the Nagatina swamps, from the east by the Moscow River, Kolomenskoye over time becomes an important stronghold in the fight against external enemies, and is also repeatedly used by invaders to house troops in preparation for siege of Moscow.

For the first time in Russia, the path from Moscow to Kolomenskoye was divided by mileposts (hence the saying: “from Kolomenskoye milepost”).

Kolomenskoye is often mentioned in chronicles in connection with the struggle of the Russian people against the Golden Horde and the Crimean Khans; in 1380 Dmitry Donskoy stayed here after his victory over the Tatars on the Kulikovo field.

Kolomenskoye is rapidly growing, developing and becoming a large grand ducal estate near Moscow. Kolomenskoye was the favorite dacha of Tsars Ivan the Terrible and Alexei Mikhailovich, who built it here in 1667-1670. wooden palace. The palace was built by the best masters XVII century and was the most beautiful wooden structure in Rus'. Here in the summer the royal family rested for a long time, watching the exercises of the Streltsy troops and falconry fun. At that time it served as a house church stone temple The miraculous icon of the Kazan Mother of God, connected to the wooden palace by a covered passage.

Kolomenskoye is rapidly growing, developing and becoming a large grand ducal estate near Moscow. Kolomenskoye was the favorite dacha of Tsars Ivan the Terrible and Alexei Mikhailovich, who built it here in 1667-1670. wooden palace. The palace was built by the best masters XVII century and was the most beautiful wooden structure in Rus'. Here in the summer the royal family rested for a long time, watching the exercises of the Streltsy troops and falconry fun. At that time it served as a house church stone temple The miraculous icon of the Kazan Mother of God, connected to the wooden palace by a covered passage.

From the ancient manor park, only oak trees have been preserved in its southern part. Four oak trees with powerful trunks are 800 years old. They are contemporaries of Moscow.

The Church of the Ascension of the Lord from 1532, an unrivaled example of church architecture, has survived to this day. first half XVI century, included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is believed that the church was built by Grand Duke Vasily in honor of the birth of his son, the future Tsar Ivan the Terrible. It amazed contemporaries with its beauty and grandeur, rising on the steep bank of the Moscow River. The height of the temple is 62 meters; in the 16th century it was one of the tallest buildings in Russia.

first half XVI century, included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is believed that the church was built by Grand Duke Vasily in honor of the birth of his son, the future Tsar Ivan the Terrible. It amazed contemporaries with its beauty and grandeur, rising on the steep bank of the Moscow River. The height of the temple is 62 meters; in the 16th century it was one of the tallest buildings in Russia.

In the village of Kolomenskoye - Dyakovo - there is a unique architectural monument of the 14th century - the Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist - the prototype of St. Basil's Cathedral on Red Square.

Peter I spent his childhood years in Kolomenskoye. Here the young prince organized exercises of “amusing troops”, river cruises on specially designed ships, stayed here after the capture of Azov (1696) and before the ceremonial entry into Moscow after the victory at Poltava (1709). Four cannons that stand on the banks of the Moscow River to this day remind us of Peter’s victories.

Later, Kolomenskoye served as the summer residence of Peter II, Anna Ioanovna, Elizaveta Petrovna, and Catherine II. Lush festivities and royal hunts were held here.

Kolomenskoye in the XVII-XVIII had typical features estate, it had everything necessary for the royal family. Kolomenskoye was the center of the palace volost, consisting of 9 villages and 4 villages - some of them are located on the territory of the modern Nagatinsky Zaton district.

The main street of the village - “Bolshaya” (XVI century) had oak flooring, which was discovered in the 1960s when laying a water pipeline. The main population of the village were peasants. Also living here were carpenters, grooms, bridge workers, watchmakers, tilemakers, fishermen, and gardeners who served the palace household.

Fruit orchards have been created in Kolomenskoye for many centuries. According to the inventory of 1701, there were six gardens with 6 thousand fruit trees; in 1813, the number of fruit trees increased to 15 thousand.

Kolomenskoye gradually grew and merged with the surrounding villages - Shtatnaya Sloboda and Sadovniki in the south and with Novinki and Nagatin in the north. At the end of the 19th century, the village of Kolomenskoye became a large settlement.

By this time, the large orchards of Kolomenskoye, which had been created over many centuries, turned out to be economically unprofitable: Moscow demanded vegetables. The peasants uprooted fruit trees and planted vegetables in their place.

In the 1930s, the collective farm “Garden Giant” was organized in Kolomenskoye, which had a vegetable farming area. The fields of the collective farm spread widely on the former Tsar's Amusement Meadows, where falconry and parades of amusing regiments took place.

The name of the village “Nagatino”, known since the 14th century, according to one version, is due to the fact that in this low-lying floodplain of the Moscow River, flooded during high water, the roads were located “on the road”, i.e. on a flooring of logs for travel and passage through the swamp; on the other hand, from the word “nogata”, which denoted the ancient Russian monetary unit of the 10th - 15th centuries.

Since ancient times, around Nagatino there have been many flooded meadows and lakes that residents could use to build and repair ships. The Nagatinskaya backwater was mentioned in 1410. In Nagatino, there is still a “backwater” (or backwater) - a bay, bay with calm, stagnant water.

In this backwater, the Moscow Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Plant was put into operation in 1936 (Rechnikov St., no. 7). The main direction of the plant's work is shipbuilding and repair of self-propelled fleets, manufacturing of ship mechanisms and lighting equipment.

A workers' settlement was built near the plant, which is the oldest residential building in the area.

The first ship was built by the plant's team in 1938. Motor ships of the Moskvich type, the so-called river trams, have become especially popular on river routes. At the same time, the plant built large series of river pusher tugs, lake passenger ships for suburban lines and their modifications for service and research purposes.

The location of the plant created the prerequisites for the formation of educational institutions - a vocational school, the Moscow River Technical School, the Moscow Institute of Water Transport (1979) - for training specialists in river shipping and shipbuilding. In 1993, all these institutions were united into the Moscow State Academy of Water Transport.

In 1960, the villages near Moscow: Nagatino, Kolomenskoye, Novinki became part of Moscow, and in the late 1960s this territory became a huge construction site. In place of the demolished wooden buildings, gardens and vegetable gardens, blocks of multi-storey residential buildings grew up.

In 1960, the villages near Moscow: Nagatino, Kolomenskoye, Novinki became part of Moscow, and in the late 1960s this territory became a huge construction site. In place of the demolished wooden buildings, gardens and vegetable gardens, blocks of multi-storey residential buildings grew up.

On the right bank of the Moscow River, after the reconstruction of the Nagatinskaya floodplain and the construction of a new river bed, the Nagatinskaya embankment was built in the 60s, made of precast reinforced concrete, lined with granite. The architectural solution for the development of residential buildings on the side of the Moscow River - in the form of houses stylized as sails - creates a modern facade of the area.

In 1969, the Nagatino Bridge was built near Nagatino, which connected Nagatino with the Kozhukhovo district, Proletarsky Avenue passed here (now it is Andropov Avenue), and the Kolomenskaya metro station was built.

In 1981, on the site of the fields of the former vegetable-growing collective farm “Garden Giant”, the construction of another residential area continued (Kolomenskaya Street and Kolomenskaya Embankment - former streets Srednyaya and Nizhnyaya in the village of Kolomenskoye).

The territory of the Nagatinsky Zaton district also includes a large green area located on a peninsula to the north of the residential areas of the district - the Nagatinskaya floodplain.

A floodplain is a part of a river valley bottom that is flooded only during high water. The average height above the river level is 1 - 1.5 m. Before the construction of the Perervinsky hydroelectric complex in the 1930s, the area was flooded during floods and was very swampy. At the end of the 60s, the Nagatinskaya floodplain was completely reconstructed. Extensive work was carried out here to eliminate swamps, a straightening canal 3.5 km long was built, as a result of which an island with an area of over 150 hectares was formed, divided by the Nagatinsky Bridge. On the eve of the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution, a park named after. 60th anniversary of the October Revolution (architect V.I. Ivanov), which occupies more than 100 hectares. In 1985, the Southern River Station was built on the floodplain (architect A.M. Rukhlyadev) - this is the second river gate of Moscow after the Northern River Station. The station building is made of reinforced concrete structures and glass, stretches along the shore, and is decorated with a tower with a spire. On the territory of the floodplain there is a children's goods fair - "Kolomenskaya" fair.

From the ancient villages near Moscow, on the territory of which the Nagatinsky Zaton district is located, currently only their names have been preserved, which are given to the streets, embankments, bridges, metro stations: Kolomenskaya street, Kolomenskaya embankment, Kolomenskaya metro station, Nagatinskaya embankment, Nagatinsky bridge, street New items. The central street of the village of Kolomenskoye - Bolshaya Street - has survived to this day with the same name.

The names of the remaining streets are related to shipbuilding production and landscape features of the area: Shipbuilding Street (adjacent to the Moscow Shipyard), Rechnikov Street, Yakornaya Street, Zatonnaya Street. The name “Maple Boulevard” was given in connection with the planting of various types of maple along the boulevard.

The names of the remaining streets are related to shipbuilding production and landscape features of the area: Shipbuilding Street (adjacent to the Moscow Shipyard), Rechnikov Street, Yakornaya Street, Zatonnaya Street. The name “Maple Boulevard” was given in connection with the planting of various types of maple along the boulevard.

The Nagatinsky backwater has its own coat of arms, which is a Moscow-shaped shield, beveled on the left with a raised silver leash. In the upper purple field there is a silver image of an ancient settlement - three ancient dwellings, fenced with a five-pointed palisade with a gate. The river symbolism of the area is reflected in the form of crossed silver hammers, an ancient river anchor and a modern river anchor in the lower green field of the coat of arms.

Mysterious. According to N.N. Belyanchikov, it is formed from the phrase “on the road”, i.e. a swampy place, fortified with brushwood, logs and bulk earth. However, this is unlikely, since there are no known cases in the language of the formation of Russian toponyms from a combination of a preposition and a noun, and is a typical “folk” explanation for an incomprehensible name. In addition, in the oldest documents, the name of the village was always written with “o” in the first syllable: “Nogatinskoe”, “Nogatino”. In Rus' in the 9th-11th centuries. Arab silver dirhams were called nogat, cut in half or into four parts. The original meaning of the Arabic word "nogata" is cash. Therefore, Academician M.N. Tikhomirov proposed a version of the origin of the toponym from this word. Considering the navigability of the Moscow River and the inevitability of “myt” - the collection of monetary duties levied on merchant caravans, one could agree with it. But in the XIII century. - the time preceding the first mention of the village in sources, nogat, undoubtedly, were no longer in circulation in Rus'. On the other hand, it is possible to assume the possessive nature of the name. However, according to academician S.B. Veselovsky, the version that Nagatino got its name from a person who bore the nickname “Nogata” should be rejected, because it is not known as a personal nickname. M.N. Tikhomirov pointed out another possible origin of the name of the village - from the Old Russian word “nogatitsa” - upper room. Be that as it may, the question of the origin of the name remains open, although there is no doubt that Nagatino is one of the most ancient settlements in the Moscow region.

It was first mentioned in 1331 in the will of the Moscow prince Ivan Danilovich Kalita, who transferred the village to his youngest son Andrei. Obviously, even then it was a fairly large settlement. In 1353, the village passed from Prince Andrei Ivanovich to his son Vladimir, later a famous associate of Dmitry Donskoy, who at the beginning of the 15th century. bequeathed it “with all the meadows and villages” to his wife Elena Olgerdovna as an “oprichnina” possession. The will specifically stipulated his inviolability: “And my children do not enter into ... their mother’s inheritance.” Starting with Elena Olgerdovna, Nagatin was owned by three generations of princesses of the Serpukhov family - in addition to her, her daughter-in-law Vasilisa, the widow of Prince Semyon Borovsky, and granddaughter Maria Yaroslavna. The latter married the Grand Duke of Moscow Vasily the Dark, and Nagatino again fell into the hands of the Moscow Grand Dukes and became part of the palace Kolomna volost.

Initially, the village was obviously an association of farm-type villages of 1-3 households with a central estate at the head. In the XV-XVI centuries. Chaotic buildings are being replaced by more compact ones. On plans XVIII V. Nagatino looks like a three-row village with two streets stretching from southwest to northeast towards the mouth of the “Nogatinskaya” backwater.

It is difficult to say whether a church existed in Nagatin. It is possible that there was some kind of wooden temple here, which was subsequently not restored due to construction in the middle of the 16th century. churches in Kolomenskoye and Dyakovo. In any case, the church is not mentioned in known sources.

The main occupation of the Nagatin peasants was agriculture, although natural conditions did not promote arable farming. The Moscow River then had a different channel, not far from the village it changed its direction from northeast to southeast and south, and its frequent floods were followed by a chain of oxbow lakes - the remnants of its old channel, including lakes Novinskoye and Nagatinskoye . Along the entire right low-lying bank stretched a wide strip of water meadows, which constituted the main wealth of the village. Documents characterize the local lands as “thin”, and therefore, relatively early, highly skilled vegetable gardening, which was commercial in nature, acquired particular importance in the peasant economy, especially in the 18th-19th centuries. Mainly cabbage and cucumbers were grown. All sources, without exception, considered the flood meadows with their dense grass to be the main wealth of the Nagatin lands. But the activities of local residents were not limited to this. This is indirectly evidenced by the will of Princess Elena Olgerdovna, which mentions “city nogatins with duties.” It can be assumed that this was pilotage or shipbuilding and ship repair work, for which the backwater - the river bay of the Moscow River - was especially convenient.

The sources allow us to trace the demographic development of the village. According to the census of 1646, in the “village that was close to the palace village of Kolomenskoye, which was the village of Nagatinskoye near Lake Nagatinskoye,” 42 male souls lived in 21 courtyards. In the 70s of the 17th century. it contains 16 households and 106 peasant souls. A century later, according to the acts of the General Land Survey, there were already 52 households and 268 residents in Nagatin.

For several centuries Nagatino was in the Palace Department. By decree of Emperor Paul I in 1797, it, along with other villages and hamlets, was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Department of Appanages, in contrast to Kolomenskoye, which was considered the personal property of the tsar. To manage the appanage peasants, special orders were created, one of which was called Kolomensky, but with a control center in Nagatin. In 1811, there were 28 villages under the order. In 1848, there were 16 villages and villages and 13 thousand people of both sexes.

In the 18th century An influx of Old Believer population begins in Nagatino and neighboring Kolomenskoye. According to 1859, there were 89 households and 673 people, half of whom were Old Believers (in 1826 there were 176 people, in 1865 - 217 people). According to N.N. Belyanchikov, in Nagatin there lived peasants with such aristocratic names, like the Golitsyns and Khovanskys. They considered themselves descendants of these famous princely families.

After the reform of 1861, appanage and landowner peasants were given equal rights. The Nagatinskaya volost was formed. In the village there was a volost administration, a court, and taverns. The further life of local peasants was in many ways similar to the life of other neighboring villages near Moscow. Although Nagatinsky peasants were officially released in 1864, the conditions of their release worsened their previous situation - in particular, they were forbidden to fish in the Moscow River and Lake Nagatinskoye. For their own land, they annually had to pay 4 rubles 7 kopecks from each per capita plot - first 2 years to the Piece Department, and then 49 years to the treasury.

The main occupation of Nagatin peasants since the 18th century. becomes gardening. Considering that the best lands and meadows belonged to the Palace Department (these meadows were often rented out), the peasants suffered from a lack of land and frequent crop failures, and the results of their work on the palace tithe arable land were also low. Therefore, in 1763, the tithe arable land was destroyed, the lands were transferred to the peasants for a certain, mostly monetary rent. The villagers began to plant vegetables (cabbage and cucumbers) on their arable land and sell them in Moscow. Gradually, vegetable gardens began to be placed directly along the banks of the river, which ultimately led to the destruction of water meadows.

According to the 1869 census, there were 304 men and 333 women living in the village. Data from 1876 indicate the presence of 116 farms, a volost government, 1 tavern, and 3 vegetable shops. At this time, the peasants controlled 390.5 dessiatines of land, and, characteristically, flooded meadows accounted for only 29.1 dessiatines, and the size of the estate land (137 dessiatines) exceeded the size of arable land (112.2 dessiatines). Grains (rye, oats) were no longer sown; their place was completely taken by potatoes, almost all of which were grown for sale. The peasants completely switched to a single-field farming system, i.e. All arable fields were planted with potatoes every year, the land did not rest. With such exploitation, it quickly depleted, requiring fertilizer, and therefore the peasants had to transport manure from Moscow. One dessiatine of potatoes required 50-60 carts, for which 20-30 rubles were spent. The proximity to Moscow allowed us to make two or three trips a day. The considerable cost of fertilizer, however, was more than paid for by the harvest, so the most profitable activity in free time from field work was considered to be driving for manure, which the peasants did all winter. Other vegetable crops, which served as the main source of income for peasants, required even more fertilizers.

To prepare the land for planting, they used a special garden plow - more massive than usual, with a greater distance from the frame to the end of the coulters and a smaller slope to the frame, which allowed for deeper plowing. Cabbage was planted in squares in the beds, using special planting stakes. Twice or three times a summer weeding was carried out, for which they used a modification of the hoe - a weeder. The harvest was done in mid-October. Cucumbers were planted along the ridges, weeded two or three times, and harvested in July - mid-August. It was typical to plant two crops in the same place in the same year - cabbage after cucumbers or cucumbers between cabbage rows.

Cabbage was fermented in doshniks - huge tubs of up to 1,500 poods, dug into the ground, and in small tubs (this cabbage was considered better and was used for personal consumption, unlike “doshnikova” - for sale), cucumbers were pickled in tubs, but such pickling was expensive and not accessible to all peasants. Intensive and urgent vegetable growing work could not be carried out by one family, so most farms hired workers to care for plants (watering, weeding), harvesting and chopping cabbage. Day laborers were hired for the whole summer, which was profitable for them and attracted them here in great numbers, so that sometimes the peasants of villages more remote from Moscow, which were not part of the gardening region, no longer had enough hired labor.

It is clear that such a highly commercial nature of the economy was accompanied by the stratification of the peasantry. Thus, if in 1899 a third of farms hired workers, then about 16% did not cultivate their plot. Almost all peasant farms had horses, 63.4% kept cows. Almost half of the families were engaged in crafts, albeit the simplest ones: men in their free time in winter transported ice, snow, sand, while women were engaged in such an easy task as winding cotton threads on spools. In 1881, 30% of female workers were engaged in this, in 1899 - 10%. Before the reform of 1861, there was a specific school in the village, then the children of Nagatinsky peasants studied in two schools in the village of Kolomenskoye - zemstvo and private; In addition, some Old Believers taught children at home. In 1899, there were 219 literate and student people in the village (out of a population of 733). In the early 1900s, a stone three-class school was built between Nagatin and Novinki. In the 19th century A ship repair plant is being built in Nagatinsky Zaton, next to which a factory settlement appears.

After 1917, local peasants united into the collective farm “Garden Giant”; the factory settlement also developed, which was transformed into a workers’ village. In 1960, Nagatino became part of the city, and city blocks were built on the territory of the ancient village. Nowadays only the name reminds of the former village.

Kolomenskoye

Another village located not far from Nagatin was Kolomenskoye, which, thanks to the events that took place there, remained forever in Russian history.

The name of the village, apparently, is derived from the Slavic word “kolo” (in modern language the word “outskirts” is known) and can be translated as “neighborhood”. According to M. Vasmer, the origin of the name is also possible from the word “koloimische” - cemetery, derived from the Finnish “kalma” - grave or “kalmisto” - grave.

There is a legend that the village of Kolomenskoye was founded in 1237 by residents of Kolomna, who fled their hometown from the invasion of Batu Khan. This is where the name of the village of Kolomenskoye supposedly came from. But this explanation is of a later nature and, obviously, is the fruit of historical fantasy.

The village was first mentioned as a grand ducal patrimony in 1331, when the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan Kalita gave it in his spiritual will to his youngest son, Prince Andrei. Located on the Serpukhov road, Kolomenskoye was one of the Moscow estates of his son, Prince Vladimir Andreevich Serpukhovsky. In the XIV century. it was also a small princely estate, which included the prince’s courtyard with services and a village.

The rapid rise of Kolomenskoye was facilitated by its convenient geographical and strategic position at the junction of land and water roads going to the south. Kolomenskoye was mentioned more than once in chronicles in connection with the struggle of Moscow with the Golden Horde and the Crimean Khanate. Dmitry Donskoy returned through the village after the victory on the Kulikovo Field in 1380. In 1408, Khan Edigei, during his campaign against Moscow, set up his camp in Kolomenskoye. In 1521, the Crimean Khan Mohammed-Girey raided the capital from there. Grand Duke Vasily III went out to the south twice, in 1528 and 1533, to meet the Tatar hordes. In 1533, from Kolomenskoye, he led military operations against the Crimean Khan Safa-Girey. Later, Ivan the Terrible made his campaign against Kazan through Kolomenskoye. And it is no coincidence that it was during this period that the Church of the Ascension (1532) and the Church of John the Baptist in the neighboring village of Dyakovo were built in Kolomenskoye. The chronicler of the Church of the Ascension wrote that that church was “greatly wonderful in its height and beauty and lightness,” which had never happened before in Rus'. In September of the same year, at its consecration, the Metropolitan, the brothers of the Grand Duke and the boyars feasted for three days.

During the time of Ivan the Terrible, there was a palace and two churches in Kolomenskoye, built in the first half of the 16th century. St. George's Bell Tower, all the necessary outbuildings. The notes of the German guardsman Heinrich Staden mention that in 1571, the Crimean Khan Devlet-Girey, making a campaign against Moscow, ordered “to set fire to the pleasure yard of the great sovereign in Kolomenskoye, a mile from the city.” In 1591, the son of Ivan IV, Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich, again rebuilt the village devastated by the Tatars. He built another palace, which, however, did not last long. The Time of Troubles began in Russia. In 1605, False Dmitry I set up his camp near Kolomenskoye. And at the beginning of October 1606, I.I. set up a fortified camp here. Bolotnikov and began the siege of Moscow.

On the plan of Moscow by Isaac Massa 1606-1607. depicts a picture of the battle between the troops of Tsar Vasily Shuisky and troops led by Ivan Bolotnikov, which took place in Kolomenskoye on December 2, 1606. The picture shows the buildings of the estate, the Church of the Ascension, the entrance gate located near the temple, and part of the stone fence are visible. After the deposition of Tsar Vasily Shuisky in 1610, the new impostor Azhedmitry II stood in Kolomenskoye with his troops.

XVII century became the time of greatest prosperity for the royal estate. After the accession of Mikhail Romanov, the village of Kolomenskoye, as a victim of the Poles, received benefits and exemption from state duties. From that time on, intensive construction of the royal estate began. First of all, a large wooden palace was laid, consisting of many towers and mansions, connected by vestibules and passages. In the middle of the 17th century. In memory of the deliverance of Moscow from Polish captivity, the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God was built. It was intended as a house temple for the new royal palace and was connected to it by a warm passage. At the same time, the Vodovzvodnaya Tower was built to supply the estate with water.

According to the description of 1646, in the village there was a courtyard of the great sovereign, “and another courtyard of the sovereign’s stables,” 6 courtyards of the church clergy, 3 courtyards of church servants, “and in the village there are 52 farmsteads of peasants and peasants.”

In 1645-1671. The construction of the palace complex was continued by Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, who paid a lot of attention to the expansion and decoration of the palace. By its nature, the layout of the palace was a multiple repetition of an ordinary residential log cage. They were grouped in a wide variety of combinations into separate complexes, united by covered passages. The palace buildings included 270 rooms. United in asymmetrical groups, the various log houses ended in chorus with the picturesque roofs of the various types. Additional rooms were built underneath them in the form of towers and lighthouses. In the construction of roofs, the art of Russian craftsmen reached its highest artistic expression. Here there were ceilings: “cube”, “domestic”, “octagonal tent”, “barrel”, “crossed barrel”, “double crossed barrel”, “wedge roof”, “tent”. Not only the shape of the roofs, but also the very nature of its scaly surface of emerald and turquoise colors with gilded combs, figured weather vanes, and painted valances gave the palace a colorful outfit.

It was no less diverse interior decoration in chorus. Colored tiled stoves, a patterned mesh of mica endings, tables painted in the Chinese style, benches covered with patterned fabrics made up the decoration of the palace. This grandiose structure caused amazement among contemporaries. It was compared to a precious box that had just been taken out of a casket. Simeon of Polotsk called the palace in Kolomenskoye the eighth wonder of the world: “... The ancient world reads seven wondrous things, this house is the most marvelous time to have ours.... Osmo now appeared in Moscow, when this royal house of yours was completed, In every way wondrous, red and rich, splendid on the outside, richly golden on the inside.”

In the second half of the 17th century. Kolomenskoye was the center of a vast palace estate. Four villages (Dyakovo, Borisovo, Saburovo, Brateevo) and eight villages (Batyunino, Novoye Zaborye, Chertanovo, Kotel, Nagatino, Kuryanovo, Besomykino, Belyaevo, Maryino and Shipilovo) were assigned to it.

In the first years of the reign of Peter I, the village of Kolomenskoye retained its significance as a palace estate. In Kolomenskoye, Peter spent his childhood years, participating in the maneuvers of amusing regiments. But later the tsar visited his village near Moscow less and less often. In 1696, after the capture of Azov, Peter I stayed for several days in Kolomenskoye. In 1709, after the victory over the Swedes near Poltava, the tsar again came to Kolomenskoye and from here made a ceremonial entry into Moscow.

After the capital of the Russian Empire was moved to St. Petersburg, Moscow gradually began to lose its importance. The Tsar's village near Moscow shared the fate of the capital. It has lost its former significance and is becoming an estate, performing economic functions of cultivating the land, growing gardens, protecting and repairing palace buildings.

Meanwhile royal palace was dilapidated, although, on the personal instructions of Peter I, white stone foundations were laid under it. Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, born in Kolomenskoye, lived in the palace for a long time, which maintained the preservation of the existing buildings.

In 1768, Catherine II ordered the wooden palace to be dismantled. Acacia bushes were planted along the contour of its foundations. On the banks of the Moscow River north of the Church of the Ascension, a stone palace was built for the empress in 1787. The building had two stone lower floors and two wooden upper floors. There were entrance porticos on the east and west. The main palace entrance was connected to the western porch of the Church of the Ascension by wooden walkways.

In 1812, Napoleon’s troops were stationed in Kolomenskoye, which caused significant damage to the estate. The walls of many buildings and the Catherine Palace were damaged, and gardens were partially cut down. In 1813, the palace of Catherine II was dismantled.

In 1825, on the site of a demolished building designed by architect E.D. Tyurin, a palace complex was built for Emperor Alexander I. It consisted of three separate buildings, united by a light transparent colonnade, and a one-story wooden pavilion, which has survived to this day.

In 1835, Emperor Nicholas I visited Kolomenskoye and decided to build a palace for himself according to his taste. The development of the project was entrusted to the court architect Stackenschneider. According to the project, a huge barracks-type palace was supposed to be attached to the Church of the Ascension, and at the other end a second church was built, modeled on the Church of the Ascension. This project was not implemented.

In 1859 a competition was announced for new project palace A version of the project by architect K.A. has been preserved. Tone, also completely ignoring the existing architectural ensemble of the village.

In 1901, on the instructions of the Palace Office, a project was carried out to divide the territory of the Sovereign's courtyard and the historical estate into separate plots for sale as dachas. Fortunately, this project was not implemented.

Kolomenskoye became a state museum-reserve in 1923 as a branch of the Intercession Cathedral museum (St. Basil's Cathedral). The first director of the Kolomenskoye Museum was the famous architect and restorer P.D. Baranovsky. Since 1928, the Kolomenskoye Museum has become a branch of the Historical Museum. In 1966, by order of the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR, it was transformed into the Kolomenskoye State Museum-Reserve and since 1971 it has become independent. It included 18 architectural monuments, 12 archaeological monuments and 9 natural monuments. The total number of items stored in the museum’s funds is close to 45 thousand.

Dyakovo

No less famous was the village of Dyakovo, which now forms the southern part of the Kolomenskoye nature reserve and is located on the high right bank of the Moscow River. From the north it is fenced off from Kolomenskoye by the deep and picturesque Golosov ravine, called Bezymyanny in ancient documents.

In surviving documents, Dyakovo is first mentioned in the spiritual letter of Prince Vladimir Andreevich Serpukhovsky, cousin of Dmitry Donskoy, who bequeathed the villages of Kolomenskoye and Dyakovo to his wife Elena Olgerdovna, daughter of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Olgerd. In his will, Prince Vladimir Andreevich stipulated that the princess’s villages were completely at her disposal: “And my children are in the mother’s inheritance and in the villages and that from the village’s inheritance I gave to my princess, they do not interfere with any matters, and in Medkino the village with the villages and in Dyakovskoe village with villages.” From that time on, Dyakovo was in the constant “oprichnina” possession of the Moscow princesses. The term “village” found in this document suggests that Dyakovo during this period was a large settlement and was the administrative center of the district, which apparently included several villages. In the middle of the 15th century. the wife of the Grand Duke of Moscow Vasily the Dark, Maria Yaroslavna, exchanged Dyakovo with her aunt Princess Vasilisa. Initially, she intended to give the village to the Nativity Monastery in Moscow, which served as the tomb of the Moscow princesses and in which she bequeathed to bury herself. However, later she changed her decision in favor of her son - the future Grand Duke Ivan III. So Dyakovo again fell into the possession of the great Moscow princes and became their palace fiefdom. In all subsequent documents it is mentioned together with neighboring Kolomenskoye as its “settlement”.

According to archaeological data, the village was originally located not where it was later, but on the southern slope of the Golosov ravine, now partially occupied by the gardens of the Experimental Garden Farm. Written sources, for the most part still unpublished, despite the fragmentation of their news, allow us to trace the internal life of the village, starting from the 17th century.

Judging by the description of 1646, there were 30 households in Dyakovo, where about 80 people lived. Calculating the total number of inhabitants is complicated by the fact that in documents of the 17th century. Usually, only men were recorded—yard owners and their sons. Women were mentioned only when the widow ran an independent household. Thirty years later - in 1676-1677. in the village there were 27 households, in which there were about 180 souls of both sexes. We see the same number a century later - according to the data of the General Land Survey of the second half of the XVIII V. However, the number of residents increased somewhat - there were already 230 people. A significant increase in population in the village occurred in the first half of the 19th century. In 1859, there were already 70 households with 500 inhabitants in Dyakovo.

According to materials from the 17th century, the population of Dyakovo, as well as Kolomenskoye, was divided into four categories. The bulk of the inhabitants were draft peasants who worked in the arable land. Of the three dozen households that made up the village in 1646, 21 belonged to draft peasants. Another category of village residents were “bobyli” - the so-called “uncultivated” peasants, who, as a rule, did not have the opportunity to support their family. Village artisans, also called bobyli, could also belong to their number. In the village there were also the courtyards of the church clergy of the local Church of John the Baptist - priests, deacon, sexton, church watchman. The clergyman was, as a rule, on the sovereign's allowance (“ruge”), which was not paid very regularly and therefore was often replaced by the provision of land: arable land, hayfields and pastures, which the clergyman used for his needs.

The natural conditions of Dyakov and Kolomenskoye were not conducive to arable farming. And therefore, approximately from the middle of the 17th century. The kings started gardening here, which was serviced by sovereign gardeners specially selected from the tax peasants. The oldest mention of them in Dyakovo was found on two white stone tombstones found in the local (now defunct) cemetery. The inscription on one of them reads: “Summer 7157 (1649. - Author) January 2nd day, the servant of God Philip Kirilov, the sovereign gardener, passed away.” Nearby was the tombstone of his wife, the daughter of peasant Kirill Panteleev, who died two years later.

Serving as a sovereign gardener required certain qualifications and special knowledge of agronomy. Apparently, there were also recruitments of peasants to become gardeners. Apparently, the mention in the census books of 1676-1677 is connected with this. a number of people who came to Dyakovo from other areas, sometimes very remote. From this source it becomes known that Yakushka Rodionov came to the village from neighboring village Kozhukhovo, Vaska Danilov arrived from Ozeretskoye near Moscow, Mishka Yakovlev was from Belarus, and Pronka Yakovlev was from the distant northern Totma.

Gardeners were usually on the sovereign's salary, which in some cases was replaced by the lease of land for use. Service as a gardener was obviously hereditary, and attempts to move from gardeners to draft peasants were strictly suppressed.

In the vicinity of Dyakov, there were up to six sovereign gardens, which employed up to two dozen gardeners. Dyakovo Gardens of the 17th century. - these are far from the gardens that we usually imagine. For that time there was no difference in the concepts of “garden” and “vegetable garden”. The garden was combined with a vegetable garden according to ancient agricultural patterns - beds with vegetables were located between garden trees and bushes. In the documents of that time, lists of garden crops were preserved: apple trees, pears, duli (a variety of pears), white and red cherries, gooseberries, red and black currants, plums, walnuts, and raspberries grew in the gardens. Vegetables cultivated included cabbage, cucumbers, radishes, parsley, beets, spinach, and watercress. A “cage” was also built here - an artificial pond for keeping fish. Gardens required specially selected conditions for their placement: soil, microclimate, slope of the slope, relationship to the cardinal points, etc. These conditions were best met by the southern slope of the Golosov ravine, where Dyakovo was located, and therefore in 1662 the village was moved to a new location - along the Moscow River. The former place, according to the testimony of elected peasants, was “enclosed in the sovereign’s garden.”

The appearance of the village in the second half of the 17th-18th centuries. was quite typical for that time: the main street, stretched in one row along the cliff of the Moscow River terrace above the floodplain, with houses on both sides. There were 11 acres of land under the courtyards, and the average size of a personal plot was thus approximately half a hectare (after collectivization, the largest big size personal plot was 25 acres). Next to the peasant houses were the Poteshny and Konyushenny sovereign courtyards, which were, as it were, branches of the palace buildings in Kolomenskoye. Here, in a tax-paying peasant yard, small sovereign mansions were erected, often used by Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. There is a rather curious description of them in one of the documents of that time: “The sovereign’s mansion has two underground huts, and in them there are tsenin stoves, the doors and windows in both huts are covered with red cloth, the gates are folded, the huts and gates are covered with planks, there are four Streletsky huts near the yard.” .

Dyakovo was a wealthy village. The wealth of the peasants was evidenced by the rich ornamentation of the houses, decorated with saw-cut carved frames, valances, and ridges. Many houses had tiled stoves. Archaeological research A.V. Nikitin showed that in the house construction of the villages of Kolomenskoye and Dyakova in the 18th-20th centuries. hardware was used (door handles, locks, keys, door linings, etc.) from the wooden Kolomna Palace of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, bought by peasants when dismantling the monument in the second half of the 18th century.

After the death of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the palace buildings in Dyakovo fell into disrepair. Under Peter I it was built new capital, and, as a consequence of this, there is a sharp drop in demand for horticultural crops on the Moscow market. Therefore, local peasants are switching to primarily growing vegetables - mainly cucumbers and cabbage. They were grown in huge quantities and sold in Moscow markets. A deep tank dug in the ground and lined with bricks for pickling cabbage in the courtyard of the house of peasant Ilya Kvashnin has been preserved. According to sources, salted cabbage and cucumbers from Dyakovo were supplied to the royal table in St. Petersburg. The village retained its gardening profile until the middle of the 20th century. Hence the humorous nickname of local residents - “kocheryzhniki”.

Ancient Dyakovo is famous for the Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist, preserved in it from the palace complex, one of the few in the Moscow region that survived from the 16th century. The temple consists of the main altar and five chapels: Metropolitan Peter, the Conception of John the Baptist, the Apostle Thomas, the Conception of St. Anne and a choir chapel in the name of Tsar Constantine and his mother Helen, connected by a gallery. Exact date construction of the temple is unknown. First mention and detailed description church dates back only to 1631-1633. Since the temple is patronal, i.e. built in the name of St. John - the heavenly patron of Tsar Ivan IV, two dating options are possible: 1547 - the year of the coronation of the sovereign and 1553-1554. - their expectation of the birth of the heir Ivan Ivanovich. The fact that two of the six thrones are “Zachatievsky” makes us lean more towards the latter dating. This is supported by observations of the architecture of the church.

The fragmentation of the internal space of the temple into separate closed spaces, each of which is crowned with a separate dome, caused many researchers of the monument to associate it with the Intercession Cathedral, better known as St. Basil's Cathedral, created in 1555-1561. This method of constructing the composition of the temple is believed to have been borrowed from Russian wooden architecture, the buildings of which consisted of isolated log cabins - “cages”, which made it possible to freely vary the plan of the structure. Certain decorative elements and the presence of an open belfry for hanging bells on the western facade suggest that craftsmen from Pskov took part in the construction of the temple.

The Church of John the Baptist in the village of Dyakovo was immediately conceived as a parish church, in contrast to the royal house Church of the Ascension in neighboring Kolomenskoye, designed for a narrow circle of close associates: its total area is 400 square meters. meters versus 78.5 sq. meters of the Church of the Ascension. The height of the central pillar without the cross is 34.5 meters. The temple was not painted in the usual sense. However, during restoration work in 1960, a painting with whitewash on a red brick background was discovered on the dome - a circle with a diameter of 1.2 meters with spirals extending from it. This composition is a solar symbol.

Often on the patronal holiday, Russian tsars, starting with Ivan the Terrible, defended a prayer service in the church. In the last decade of the 17th century. The Dyakovo church was used by both residents of the villages of Dyakovo and Kolomenskoye, as well as residents of such remote villages as Black Mud (now). There was a cemetery next to the temple, which was barbarically demolished during the years of Soviet power. Many of the gravestones were real works of Russian stone carving. art XVII-XIX centuries

But Dyakovo is famous not only for its church. The name of the village is known to any archaeologist and historian. Near the village there is a high, pyramid-shaped hill - “Dyakovo Settlement”. Here was a settlement of an ancient man, fortified with ramparts and ditches. The Dyakovskoe settlement, the archaeological study of which began in the second half of the 19th century, gave the name to an entire archaeological culture - the Dyakovo culture, which occupied in the 7th century. BC. - VII century AD vast spaces of the Volga-Oka interfluve.

The history of its study is quite interesting. Z. Khodakovsky (pseudonym of the Polish historian and archaeologist Adam Czarnotsky), who was exiled to Russia in late XVIII V. for participation in the Polish national liberation movement. In his opinion, the Dyakovskoye settlement was a cult monument - a “sanctuary”. This idea could have been suggested to him by the pagan temple “Maiden Stone”, located in the cliff of the Golosov ravine about 500 meters above the mouth of the stream. Externally, it is a piece of sandstone slab measuring 2 x 1.5 meters with characteristic oval-shaped protuberances. In ancient times, sacrifices were made here. According to geologists, the bulges were formed back in the geological era by the deposition of suspended particles on boulders, but at the outer edge of the stone the bulges are supplemented with a small artificial hole for draining the blood of a sacrificial animal or installing candles. A legend that existed among local residents connects the “Maiden Stone” with St. George, who fought a battle with enemies at this place and lost his wife and children, allegedly buried under this stone. This is also associated with the ability of the stone to help women in childbirth. Hence its name. In the legend, in a hidden form, obviously, genuine events of distant times were reflected: the struggle of the church against paganism.

Local peasants began digging the site, extracting black soil for their gardens. In the 60s of the XIX century. The prominent archaeologist D.Ya. became interested in him. Samokvasov, who bought ancient things obtained by peasants during earthworks. The State Historical Museum houses his collection of things, called the “Dyakovsky treasure.” But a truly archaeological study of the monument began only in September 1875 with excavations by an employee of the Rumyantsev Museum G.D. Filimonova. The work was carried out with the aim of obtaining exhibits for the Rumyantsev Museum. For this purpose, two cross-shaped trenches were laid on the site of the fort, not even reaching the mainland. Brief information about the excavations was lost in a little-known publication. The study of the monument was continued by V.I. Sizov. The work was carried out in 1889 and 1890. at a higher level than previous researchers. Work was carried out in the 20th century. In particular, they were led by archaeologist N.A. Krenke, who used the latest natural scientific methods research (radiocarbon dating, pollen, soil and other analyses). Excavations provided insight into the internal structure of the settlement and the life of its inhabitants.

The monument is a small settlement located on the river bank in a hard-to-reach place and fortified with ramparts and ditches. A long steep ramp served as the entrance to the site. Defensive fortifications are created in such a way that the person entering passes two rows of ramparts, turning towards them with the right side, unprotected by the shield. The dwellings were semi-dugouts and long above-ground large-family houses with walls like wattle and daub, coated with clay. They were heated by stone or adobe fireplaces. Apparently, the settlement was a settlement of a large patriarchal family. The cultural layer reaches 4 meters and is divided into two main parts, between which a small layer of sand was found, which indicates a temporary cessation of life at the site. The bottom layer is dominated by textile ceramics. The design, reminiscent of a fabric imprint, was applied with a mallet wrapped in textiles. Hence the name of this ceramics. The top layer is dominated by smooth-walled molded ceramics. The unfortified settlements located nearby also date back to the first centuries of our era - villages called by local peasants “Pygon” and “Devil’s Town”. Obviously, these were settlements that branched off from the main settlement.

The ancient settlers of Dyakov were, apparently, Finno-Ugric in language and engaged in cattle breeding, agriculture, hunting and fishing. The Dyakovo herd consisted mainly of pigs, horses, cattle and, finally, small cattle. Game animals were beaver, elk, bear, wild boar, marten and badger. Metal processing, pottery and bone carving crafts actively developed at the site.

In the XI-XIII centuries. The Dyakovo settlement was occupied by a Slav settlement, which apparently existed before the Mongol-Tatar invasion. Later, people no longer settled here, and the settlement was moved north, to the slope of the Golosov ravine. In the 17th century On the site there was only a chapel, built of large bricks and decorated with multi-colored tiles, which consecrated this place, which the peasants associated with evil spirits. Traces of the chapel were discovered during pre-revolutionary excavations.

In the 60s of the XX century. Dyakovo entered. New multi-storey buildings of new buildings were advancing on the village, which for a long time resisted their onslaught. But the forces were unequal, and the confrontation ended with its demolition.

Sadovaya Sloboda

Another village of Kolomenskaya volost was Sadovaya Sloboda (or Sadovniki). As its name implies, it owes its origin to the Kolomna palace gardeners. Judging by the scribe books of the 70s of the 17th century, in Kolomenskoye there were 13 gardeners' households, in which a total of 42 male souls lived. They served the vast gardens of the royal estate. According to documents from the 30s of the 18th century, in Kolomenskoye there were two Kazan gardens (located behind the Kazan Church), Voznesensky (near the Golosov ravine) and the New garden, through which the road from the estate to the first throne went.

In their original form, the local gardens were established as “walking” gardens (they had flower beds and covered paths), and then they began to be used for growing various garden crops. These were mainly apple trees, but also pears, cherries, various varieties of plums, gooseberries, currants, and raspberries. Various vegetables were also cultivated, and six cedars were noted as rarities. Part of the harvest was supplied to the royal household, and part went on sale. As a rule, vegetables were sent to the palace, mostly prepared for future use: various kinds of jams, pickles and pickles. However, with the transfer of the capital from Moscow to St. Petersburg, the delivery of supplies to the northern capital began to be quite expensive, and therefore, from about the 40s of the 18th century. sauerkraut and salted cucumbers began to be primarily sold in Moscow markets. It was carried out either by the gardeners themselves or by “gardeners’ apprentices.”

In terms of their status, gardeners occupied an intermediate place between peasants and service people. Like peasants, they were given hay crops and “livestock allowances,” but at the same time they received cash and grain wages. It obviously wasn't bad. In any case, two gardeners have adopted dependent workers, and one has a “bought” Pole. The knowledge and experience of gardeners was highly valued. In one of the documents of the 17th century. a certain Oska Terentyev is mentioned, who asked to be transferred to peasant status, which, however, was denied to him.

The gardeners lived in a separate settlement and had their own headman, who collected taxes and monitored the completion of the work. In addition to the headman, a warden was assigned to the Kolomna Gardens in 1717. His duties included visiting the gardens, monitoring the harvest and the work of the gardeners. In 1729, another position appeared as an assistant warden - captain. Sadovaya Sloboda itself was located southwest of Kolomenskoye behind the Voznesensky Garden. In the first half of the 18th century. it had 48 households.

Throughout the 18th century. there is a gradual decline in the social status of gardeners. Like all peasants, from 1723 they began to pay a poll tax and supply recruits. When the two-ruble palace rent was assigned, it was extended to the gardeners. At the end of the century, the gardeners of Sadovaya Sloboda were finally transferred to peasants.

The amount of work they had was extremely large. In addition to cultivating the land and growing vegetables, they had to protect them, harvest the crops, and deliver them to the market or to storage. At their own expense, they were obliged to plant new trees instead of frozen and withered ones. Sometimes the obligatory supplies of food were so huge that local residents complained that they could not get such a harvest from the palace gardens and had to buy more vegetables from the peasants, “which is why they end up in ruin.” Quite often, many of the gardeners, especially experienced ones, were moved from one palace farm to another. Those who remained suffered from such displacements, since they had to pay capitation money for those who left until the next revision. All work was carried out with their own tools, and they carried out manure and water for watering vegetables on their own carts.

By decree of 1797, Sadovaya Sloboda was transferred to the Appanage Department, to the newly created Kolomna Prikaz. According to 1811 data, there were 56 families and 208 male souls. By the middle of the 19th century. 344 men and 361 women lived here. Approximately a quarter of the village's population were Old Believers (129 people in 1826, 232 people in 1865).

During the peasant reform, according to the “Regulations on peasants settled on the lands of the Palace and Tselnogo departments”, adopted on June 26, 1863, the peasants of Sadovaya Sloboda, due to their lack of land (there were only 1.1 dessiatines per revision soul) received an allotment all the land that they used until 1861. For it they had to annually pay 3 rubles 33 kopecks from each soul for 2 years to the Tselnoe Department, and then 49 years to the treasury. At the same time, they were prohibited from fishing in the Moscow River and surrounding lakes. Administratively, the village became part of the Nagatinskaya volost.

According to data from 1876, there were 146 farms, 1 tavern, and 3 vegetable shops in the village. The peasants owned 405 acres of land. The lack of land forced peasants to cultivate the most profitable crops, which from time immemorial were cabbage (more than 400 rubles of income were received annually from the tithe planted with it) and cucumbers (400-700 rubles of annual profit). Of the field crops, only potatoes were planted, and no grains were sown at all. Much attention was also paid to the gardens. At the same time, a single-field system prevailed, in which the same vegetables were planted year after year in the same place. This practice required abundant application of fertilizers, for which they traveled to Moscow, since the distance to it was only 8 miles. Despite the high cost, purchased fertilizers (various manures) paid for themselves with abundant harvests. All winter the men were busy transporting them from Moscow. In winter, the male population was also engaged in trading in Moscow harvested vegetables and potatoes, and the women were engaged in sorting, washing and preparing root crops and potatoes for this trade. There were few additional industries in the village. According to data from 1881, they employed only 45 people, including several women who made straw hats (this craft came from Kolomenskoye).

By the end of the 19th century. Social stratification begins to be observed in the village. According to 1899 data, 1,077 people lived in the village in 217 households. Of these, 46 had hired workers. At the same time, 37 farms did not cultivate their plot at all. It is characteristic that 34.8% of the village’s land holdings were estates, 53% were vegetable gardens, and only 0.5% were meadows. 166 households had vegetable gardens, 211 households had gardens. The peasants were well provided with horses (73.7% of families had them, with an average of 1.34 horses per family), but few had cows (only 23.5% of families). The horses were fed mainly on oats. Due to the low supply of their own hay (on average, only 5 pounds were harvested from a per capita plot), they additionally rented pastures and also bought hay in the villages of Podolsk district and on the Moscow River from passing barges. Gradually, additional crafts began to penetrate more and more into the peasant economy: as in Nagatin, men in winter were engaged in transporting snow, ice, sand, and women wound cotton threads on spools.

As for the level of education, before the reform, the children of peasants studied at the school of the Whole Department, and then at the zemstvo and private schools of Kolomenskoye (in 1899 there were 278 men and 111 women literate and students). According to data from 1911, the village already had its own zemstvo school and veterinary hospital.

The period of Soviet power in the history of the village was not marked by anything remarkable. In 1926, there were 285 farms and 1,191 residents in the village. Compared to pre-revolutionary times, the amount of land at the disposal of villagers did not increase much - they had 516 hectares in their use. The crafts practically no longer existed, and gardening, which had survived the difficult war and revolutionary years, was gradually revived. In the 1930s, local peasants united into the collective farm "Red Ogorodnik". In 1960, the village was incorporated into and existed until the early 1990s.,

The popular version of the origin of the name of the village of Nagatino says that it means “on the road,” that is, on a swampy place that was strengthened with brushwood, logs and an earthen embankment. But scientists refute this opinion, since the formation of toponyms from the combination of a noun with a preposition is not known in history. In addition, the name of the village originally sounded like Nogatino or Nogatinskoe. There are several other assumptions about the origin of this name, but none of them has precise confirmation. It is only known that Nagatino is one of the oldest settlements that existed in the Moscow region.

The first documentary mention of this village is found in the will of the Moscow prince Ivan Kalita dated 1331. This paper says that he transfers the village of Nagatino to his youngest son Andrei. Then Andrei’s son Vladimir, a famous associate of Prince Dmitry Donskoy, became the owner of the village, who bequeathed it to his wife Elena Olgerdovna on the condition that it would belong exclusively to her alone.

Then the village passed to three generations of princesses of the Serpukhov family, until the last owner married the Moscow prince Vasily the Dark, after which the village became part of the palace Kolomenskaya volost.

Presumably, at first Nagatino was an association of farm-type villages with a central estate, but already in the 15th-16th centuries such a chaotic layout gave way to a more orderly one. Thus, on the plans of the 18th century, the village looks like a three-row village, two streets of which stretch in the direction from southwest to northeast.

Despite the fact that the local lands were not conducive to arable farming, the residents of Nagatin were mainly engaged in agriculture. In those days, the Moscow River already had a different channel, and as a result of floods in the places of the old channel, a chain of oxbow lakes was formed, among which were also Novinskoye and Nagatinskoye lakes. The main asset of Nagatin were the beautiful water meadows located along the right bank of the Moscow River. Since the conditions for sowing grain were not very favorable, the peasants were skilled in gardening. Mostly cabbage and cucumbers were grown. According to some information that has survived to this day, it can be assumed that the men were also engaged in pilotage, shipbuilding and ship repair work - this was facilitated by the convenient river backwater.

For several centuries the village was part of the Palace Department, then, in 1797, by decree of Emperor Paul I, together with some other villages, it came under the jurisdiction of the Department of Appanages. Kolomenskoye was considered the personal property of the emperor. Orders were formed to manage appanage peasants. Among them was the Kolomna order, the center of which was located in Nagatin. In 1811, the Kolomna Prikaz was subordinate to 28 settlements, and in 1848 it included 16 villages (13,000 inhabitants).

The end of the 18th century was marked by an influx of Old Believers to Nagatino and Kolomenskoye. In 1859, there were 89 Old Believer households in the village, in which 673 people lived. Among the Old Believers there were those who bore the old Russian surnames of Golitsyn and Khovansky; they considered themselves descendants of these aristocratic families.

After the abolition of serfdom in 1861, appanage and landowner peasants acquired equal rights. The Nagatinskaya volost appeared, and a volost administration, a court, and taverns opened in the village. In fact, it turned out that the conditions for the liberation of the peasants even worsened their situation. For example, they were forbidden to fish in the Moscow River and Nagatinskoe Lake, and for their land allotment they had to pay 4 rubles 7 kopecks from each per capita allotment, first for 2 years to the Piece Department, and then for 49 years to the state treasury. The best lands and meadows belonged to the Palace Department, and the peasants were forced to occupy the remaining water meadows for their vegetable gardens, so over time they completely disappeared.

According to the 1869 census, the village had 637 inhabitants. In 1876, there were 116 farms here, as well as the volost government, one tavern and three vegetable shops. By this time, potatoes became the main garden crop cultivated by the residents. Farming was carried out using a single-field system, which greatly depleted the soil, and the peasants were forced to buy manure in Moscow. One dessiatine of land required 50-60 carts (20-30 rubles). Other crops also required fertilizers, so most In winter, the villagers were engaged in transporting manure. It was customary to plant two vegetable crops in the same place alternately or simultaneously, for example, after cucumbers - cabbage or cucumbers between cabbage rows.

Cabbage was not only sold fresh, but also fermented. For personal use, cabbage was fermented in small tubs, and for sale in huge wooden tubs for up to 1,500 pounds, they were dug into the ground and called doshniks. Doshnik cabbage was considered not as high quality as tub cabbage. Wealthy peasants also salted cucumbers in tubs. To cope with the work, many peasant families hired day laborers who worked in local gardens all summer.

In 1899, a third of farms hired day laborers; about 16% did not cultivate their plots. Almost everyone owned horses, and more than 60% of families also kept cows. Among the activities that brought in additional income, winding cotton threads on spools was popular, and in winter, men transported ice for glaciers, snow and sand.

Until 1861, a specific school operated in Nagatino, and then Nagatino children studied in Kolomenskoye - there was a zemstvo and private school there. At the beginning of 1900, a stone three-class school was built between the villages of Nagatino and Novinki, and then a ship repair plant with a factory settlement was built in Nagatinsky Zaton.

After the October Revolution, the collective farm "Garden Giant" was organized in Nagatino. The existing workers' settlement turned into a workers' settlement. In 1960, Nagatino became part of the city, and village buildings were replaced by urban buildings.

The village of Kolomenskoye was located not far from Nagatin. Presumably, the village was founded by refugees from Kolomna in 1237. They fled from the invasion of Batu Khan and stopped at the borders of Moscow. Already in 1331 Kolomenskoye was a grand-ducal estate. After Ivan Kalita, the village was owned by his youngest son Andrei, and then by his son, Prince Vladimir Andreevich Serpukhovskoy. In the 14th century, Kolomenskoye was a small princely estate with a princely court, services, and a village.

Kolomenskoye was located at the junction of land and water roads leading to the south - it was a very advantageous strategic position that contributed to the rapid rise of the village. This area saw how Dmitry Donskoy returned with victory after the Battle of Kulikovo. In 1408, in Kolomenskoye there was a camp of Khan Edigei, who was marching towards Moscow. Ivan the Terrible set out on a military campaign through Kolomenskoye, and this is not a complete list of military events that are associated with the royal estate.

In the first half of the 16th century, the Church of the Ascension was built in Kolomenskoye - a wonderful monument of Russian architecture, which has survived to this day. Around the same time, in the village of Dyakovo, located nearby, the Church of John the Baptist was built.

During the reign of Ivan the Terrible, the village already had a palace, two churches, a St. George bell tower and various outbuildings. In 1571, the warriors of Devlet-Girey burned the palace in Kolomenskoye, but in 1591, the son of Ivan the Terrible, Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich rebuilt the destroyed residence. However, the palace he built did not last long.

During the Time of Troubles in 1605, near Kolomenskoye there was a camp of False Dmitry I, and in 1606 - a camp of Bolotnikov. In early December, a battle took place in Kolomenskoye between the troops of Tsar Vasily Shuisky and Ivan Bolotnikov. After the deposition of the tsar, Kolomenskoye was occupied by another impostor - False Dmitry II.

After Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov became king, a time of real prosperity entered. The village suffered significantly from the Poles, so its residents were exempted from government duties and given some benefits. The estate began to be actively developed. The main object was a large wooden palace, which consisted of numerous towers and mansions, connected to each other by passages and vestibules. In the mid-17th century, in honor of the liberation of Moscow from the Poles, the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God was built in Kolomenskoye. This church became a house church at the new palace, and was connected to it through a warm transition. At the same time, the Vodovzvodnaya Tower was built, supplying the residence with water.

In the period from 1645 to 1671, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich significantly expanded the Kolomna palace ensemble. The palace consisted of ordinary residential cells, repeated many times, and grouped in various combinations into integral complexes, connected by passages. In total, the palace had 270 rooms. The groups of log houses were asymmetrical and ended with skillfully made roofs, which served as decoration for the palace. Among the roofs there were those arranged in various ways: “cube”, “pompoise”, “octagonal tent”, “barrel”, “crossed barrel”, “double crossed barrel”, “wedge roof”, “tent”. The surface of the roofs was scaly, emerald and turquoise, with gilded ridges, carved weathervanes and painted valances. All this gave the royal palace a very picturesque appearance.