There was a huge red wavering glow above the plant. Stories and novels

From the glow of the factory lights, Bobrov's face took on an ominous copper tint in the darkness, bright red highlights shone in his eyes, tangled hair fell haphazardly on his forehead. And his voice sounded shrill and angry.

Here he is - Moloch, demanding warm human blood! - Bobrov shouted, extending his thin hand out the window. - Oh, of course, there is progress here, machine labor, cultural successes... But think, for God’s sake - twenty years! Twenty years of human life per day!.. I swear to you, there are moments when I feel like a murderer!..

"God! But he’s crazy,” thought the doctor, who had goosebumps running down his back, and he began to calm Bobrov down.

Darling, Andrei Ilyich, leave it alone, my dear, why bother getting upset over stupid things. Look, the window is open, and there’s damp outside... Lie down, and put on your brow guard. “Manic, a complete maniac,” he thought, overwhelmed at the same time by pity and fear.

Bobrov resisted weakly, exhausted by the outbreak that had just passed. But when he got into bed, he suddenly burst into hysterical sobs. And for a long time the doctor sat next to him, stroking his head like a child, and telling him the first kind, soothing words that came his way.

VI

The next day, a solemn meeting of Vasily Terentyevich Kvashnin took place at the Ivankovo station. By eleven o'clock the entire factory management had gathered there. No one seemed to feel at ease. The director - Sergei Valeryanovich Shelkovnikov - drank glass after glass of seltzer water, took out his watch every minute and, without having time to look at the dial, immediately mechanically hid it in his pocket. Only this absent-minded movement betrayed his anxiety. The director's face - the beautiful, sleek, self-confident face of a socialite - remained motionless. Only a very few knew that Shelkovnikov was only officially, so to speak on paper, listed as the director of the building. All affairs, in essence, were handled by the Belgian engineer Andrea, half-Pole, half-Swedish by nationality, whose role at the plant could not be understood by the uninitiated. The offices of both directors were located next to each other and connected by a door. Shelkovnikov did not dare to put the resolution on any important paper without first checking the symbol made in pencil somewhere on the corner of the page by Andrea’s hand. In urgent cases, which excluded the possibility of a meeting, Shelkovnikov took on a preoccupied look and said to the petitioner in a casual tone:

Sorry... I really can’t spare a minute for you... I’m overwhelmed... Be kind enough to explain your case to Mr. Andrea, and he will then explain it to me in a separate note.

Andrea's services to the board were innumerable. The brilliantly fraudulent project of ruining the first company of entrepreneurs came entirely out of his head, and it was his firm but invisible hand that brought the intrigue to the end. His projects, distinguished by their amazing simplicity and harmony, were at the same time considered the last word in mining science. He spoke all European languages and - a rare occurrence among engineers - possessed, in addition to his specialty, a wide variety of knowledge.

Of all those gathered at the station, only this one man, with a consumptive figure and the face of an old monkey, retained his usual equanimity. He had arrived later than everyone else and was now slowly walking back and forth along the platform, with his hands elbow-deep in the pockets of his wide, saggy trousers and chewing his eternal cigar. His bright eyes, behind which one could feel the great mind of a scientist and the strong will of an adventurer, as always, looked motionless and indifferently from under swollen, tired eyelids.

No one was surprised by the arrival of the Zinenok family. For some reason, everyone has long been accustomed to considering them an integral part of factory life. The girls brought with them into the gloomy hall of the station, where it was both cold and boring, their strained animation and unnatural laughter. They were surrounded by younger engineers, tired of the long wait. The girls, immediately assuming their usual defensive position, began to pour out sweet, but long-bored naivety, left and right. Among her bustling daughters, Anna Afanasyevna, small, active, fussy, seemed like a restless mother hen.

Bobrov, tired, almost sick after yesterday's outbreak, sat alone in the corner of the station hall and smoked a lot. When he came in and sat down with a loud chirping round table Zinenok family, Andrei Ilyich experienced two very vague feelings at the same time. On the one hand, he felt ashamed for what he thought was the tactless arrival of this family; he felt a burning, depressing shame. shame for another. On the other hand, he was delighted to see Nina, flushed from her fast ride, with excited, sparkling eyes, very nicely dressed and, as always happens, much more beautiful than his imagination had pictured her. In his sick, tormented soul, an unbearable desire for tender, fragrant, girlish love, a thirst for the familiar and soothing female caress suddenly ignited.

He looked for an opportunity to approach Nina, but she was always busy chatting with two mountain students who vied with each other to make her laugh. And she laughed, flashing her small white teeth, more flirtatious and cheerful than ever. However, two or three times she met Bobrov’s eyes, and he fancied a silent, but not hostile question in her slightly raised eyebrows.

A long bell rang on the platform, signaling the departure of the train from the nearest station. There was confusion among the engineers. Andrei Ilyich watched from his corner with a mockery on his lips as one and the same cowardly thought instantly took possession of these twenty-odd people, as their faces suddenly became serious and preoccupied, their hands with an involuntary quick movement ran over the buttons of their coats, ties and caps, their eyes turned towards the bell. Soon there was no one left in the hall.

From time to time, when the sharp ringing of the signal hammer lowered the blast furnace cap, from its mouth, with a roar like distant thunder, a whole storm of flame and soot burst out to the very sky. Then, for a few moments, the entire plant emerged sharply and fearfully from the darkness, and the close row of black round cowpers seemed like the towers of a legendary iron castle. The lights of the coke ovens stretched out in long, regular rows. Sometimes one of them would suddenly flare up and glow, like a huge red eye. The electric lights mixed their bluish dead shine with the purple light of the red-hot iron... The incessant clanging and roar of iron rushed from there.

From the glow of the factory lights, Bobrov's face took on an ominous copper tint in the darkness, bright red highlights shone in his eyes, tangled hair fell haphazardly on his forehead. And his voice sounded shrill and angry.

Here he is - Moloch, demanding warm human blood! - Bobrov shouted, extending his thin hand out the window. - Oh, of course, there is progress here, machine labor, cultural successes... But think, for God’s sake - twenty years! Twenty years of human life per day!.. I swear to you, there are moments when I feel like a murderer!..

“Lord! But he’s crazy,” thought the doctor, who had goosebumps running down his back, and he began to calm Bobrov down.

Darling, Andrei Ilyich, leave it alone, my dear, why bother getting upset over stupid things. Look, the window is open, and it’s damp outside... Lie down, and put on your brow guard. “Manic, a complete maniac,” he thought, overwhelmed at the same time by pity and fear.

Bobrov resisted weakly, exhausted by the outbreak that had just passed. But when he got into bed, he suddenly burst into hysterical sobs. And for a long time the doctor sat next to him, stroking his head like a child, and telling him the first kind, soothing words that came his way.

The next day, a solemn meeting of Vasily Terentyevich Kvashnin took place at the Ivankovo station. By eleven o'clock the entire factory management had gathered there. No one seemed to feel at ease. The director - Sergei Valeryanovich Shelkovnikov - drank glass after glass of seltzer water, took out his watch every minute and, without having time to look at the dial, immediately mechanically hid it in his pocket. Only this absent-minded movement betrayed his anxiety. The director's face - the beautiful, sleek, self-confident face of a socialite - remained motionless. Only a very few knew that Shelkovnikov was only officially, so to speak on paper, listed as the director of the building. All affairs, in essence, were handled by the Belgian engineer Andrea, half-Pole, half-Swedish by nationality, whose role at the plant could not be understood by the uninitiated. The offices of both directors were located next to each other and connected by a door. Shelkovnikov did not dare to put the resolution on any important paper without first checking the symbol made in pencil somewhere on the corner of the page by Andrea’s hand. In urgent cases, which excluded the possibility of a meeting, Shelkovnikov took on a preoccupied look and said to the petitioner in a casual tone:

Sorry... I really can’t spare a minute for you... I’m overwhelmed... Be kind enough to explain your case to Mr. Andrea, and he will then explain it to me in a separate note.

Andrea's services to the board were innumerable. The brilliantly fraudulent project of ruining the first company of entrepreneurs came entirely out of his head, and it was his firm but invisible hand that brought the intrigue to the end. His projects, distinguished by their amazing simplicity and harmony, were at the same time considered the last word in mining science. He spoke all European languages and - a rare occurrence among engineers - possessed, in addition to his specialty, a wide variety of knowledge.

I

The factory whistle blared protractedly, announcing the start of the working day. A thick, hoarse, continuous sound seemed to come out of the ground and spread low across its surface. The hazy dawn of a rainy August day gave it a stern tone of melancholy and menace.

The whistle found engineer Bobrov having tea. IN last days Andrei Ilyich suffered especially badly from insomnia. In the evening, going to bed with a heavy head and constantly shuddering, as if from sudden shocks, he nevertheless soon forgot himself restless, nervous sleep, but woke up long before light, completely broken, exhausted and irritated.

The reason for this, no doubt, was moral and physical fatigue, as well as a long-standing habit of subcutaneous injections of morphine; a habit with which Bobrov recently began a stubborn struggle.

Now he sat by the window and took small sips of tea, which seemed grassy and tasteless to him. Drops ran down the glass in zigzags. The puddles in the yard wrinkled and rippled from the rain. From the window one could see a small square lake, surrounded, like a frame, by shaggy willows, with their low bare trunks and gray greenery. When the wind rose, small, short waves swelled and ran on the surface of the lake, as if in a hurry, and the leaves of the willows suddenly twitched with silvery gray hair. The faded grass clung helplessly to the ground in the rain. The houses of the nearest village, the trees of the forest stretching out like a jagged dark ribbon on the horizon, the field in black and yellow patches - everything loomed gray and unclear, as if in fog.

It was seven o'clock when, putting on an oilskin raincoat with a hood, Bobrov left the house. Like many nervous people, he felt very unwell in the morning: his body was weak, there was a dull pain in his eyes, as if someone was pressing hard on them from the outside, and there was an unpleasant taste in his mouth. But what affected him most painfully was the internal, spiritual discord that he had recently noticed in himself. Bobrov's comrades, engineers, who looked at life from the most uncomplicated, cheerful and practical point of view, would probably have ridiculed what caused him so much secret suffering, and in any case would not have understood it. Every day, disgust, almost horror, for serving at the factory grew more and more in him.

According to the turn of his mind, according to his habits and tastes, it was best for him to devote himself to office studies, professorship, or agriculture. Engineering did not satisfy him, and if not for his mother’s urgent desire, he would have left the institute in his third year.

His gentle, almost feminine nature suffered cruelly from the rough touches of reality, with its everyday but harsh needs. He compared himself in this regard to a man who had been flayed alive. Sometimes little things that were not noticed by others caused him deep and long-lasting grief.

Bobrov's appearance was modest and dull... He was short and rather thin, but there was a nervous, impetuous strength in him. The large, white, beautiful forehead was the first thing that attracted attention on his face. The dilated and, moreover, unequal size pupils were so large that the eyes, instead of gray, seemed black. Thick, uneven eyebrows met at the bridge of the nose and gave these eyes a stern, intent and almost ascetic expression. Andrei Ilyich's lips were nervous, thin, but not angry, and slightly asymmetrical: the right corner of the mouth was slightly higher than the left; the mustache and beard are small, thin, whitish, completely boyish. The beauty of his essentially ugly face lay only in his smile. When Bobrov laughed, his eyes became gentle and cheerful, and his whole face became attractive.

Having walked half a mile, Bobrov climbed a hillock. A huge panorama of the plant, stretching over fifty square miles, opened up right under his feet. It was real city made of red brick, with a forest of smoked pipes sticking high in the air - a city, all saturated with the smell of sulfur and iron fumes, deafened by an eternal, incessant roar. Four blast furnaces dominated the plant with their monstrous chimneys. Next to them stood eight cowpers, designed to circulate heated air - eight huge iron towers topped with round domes. Other buildings were scattered around the blast furnaces: repair shops, a foundry, a washing house, a locomotive, a rail-rolling plant, open-hearth and puddling furnaces, and so on.

The plant went down in three huge natural areas. Small locomotives scurried in all directions. Appearing on the lowest step, they flew upward with a piercing whistle, disappeared for a few seconds in the tunnels, from where they burst out, shrouded in white steam, thundered along bridges and, finally, as if through the air, rushed along stone overpasses to dump ore and coke into the very blast furnace pipe.

Further, beyond this natural terrace, one’s eyes ran wild at the chaos that was the area intended for the construction of the fifth and sixth blast furnaces. It seemed as if some terrible underground revolution had thrown out these countless piles of rubble, bricks of various sizes and colors, sand pyramids, mountains of flagstone, stacks of iron and timber. All this was piled up as if to no avail, by chance. Hundreds of carts and thousands of people scurried around here, like ants on a ruined anthill. White, fine and acrid limestone dust stood like fog in the air.

Even further away, at the very edge of the horizon, workers were crowding around a long freight train, unloading it. On inclined boards lowered from the cars, bricks rolled to the ground in a continuous stream; the iron fell with a ringing and rattling sound; Thin boards flew in the air, bending and springing as they flew. Some carts headed to the train empty, others returned in a line, loaded to the brim. Thousands of sounds mixed here into a long galloping roar: the thin, clear and hard sounds of masons' chisels, the sonorous blows of riveters hammering rivets on boilers, the heavy roar of steam hammers, the mighty sighs and whistle of steam pipes and occasionally dull underground explosions that made the earth tremble.

It was a scary and exciting picture. Human labor was in full swing here, like a huge, complex and precise mechanism. Thousands of people, engineers, masons, mechanics, carpenters, mechanics, diggers, joiners and blacksmiths - gathered here from different ends of the earth so that, obeying the iron law of the struggle for existence, they would give their strength, health, mind and energy for just one step forward industrial progress.

Bobrov was feeling particularly unwell this day. Sometimes, although very rarely - three or four times a year, he would have a very strange, melancholic and at the same time irritable mood of spirit. This usually happened on cloudy autumn mornings or in the evenings during the winter thaw. Everything in his eyes took on a dull and colorless appearance, human faces seemed cloudy, ugly or painful, the words sounded from somewhere far away, causing nothing but boredom. He was especially irritated today, when he walked around the rail-rolling shop, by the pale faces of the workers, stained with coal and dried by fire. Looking at their hard work while their bodies were scorched by the heat of the red-hot iron masses, and a piercing autumn wind blew from the wide doors, he himself seemed to experience part of their physical suffering. He then felt ashamed of his well-groomed appearance, and of his thin linen, and of his three thousand annual salary...

II

He stood near the welding furnace, monitoring the work. Every minute the huge flaming mouth of the furnace opened wide to absorb, one after another, twenty-pound “packages” of white-hot steel that had just come out of the fiery furnaces. A quarter of an hour later they, stretching with a terrible roar through dozens of machines, were already folded at the other end of the workshop into long, smooth, shiny rails.

Someone touched Bobrov on the shoulder from behind. He turned around in annoyance and saw one of his colleagues - Svezhevsky.

This Svezhevsky, with his always slightly bent figure, either creeping or bowing, with his eternal giggling and rubbing of his cold, wet hands, Bobrov really did not like. There was something ingratiating, resentful and angry about him. He always knew the factory gossip before anyone else and laid it out with special pleasure to those to whom it was most unpleasant; in conversation he fussed nervously and every minute touched the sides, shoulders, arms and buttons of his interlocutor.

Why haven’t you been seen for so long, my friend? - asked Svezhevsky; he giggled and squeezed Andrei Ilyich’s hand in his hands. - Do you all sit and read books? Do you read everything?

“Hello,” Bobrov responded reluctantly, removing his hand. “I just wasn’t feeling well this time.”

“Everyone at Zinenko’s missed you,” Svezhevsky continued meaningfully. - Why don’t you visit them? And the director was there the day before yesterday and inquired about you. The conversation somehow turned to blast furnace work, and he spoke of you with great praise.

“I’m very flattered,” Bobrov bowed mockingly.

No, seriously... He said that the board really values you as an engineer with great knowledge, and that if you wanted, you could go very far. In his opinion, we should not at all let the French develop the plant’s design if there are such knowledgeable people at home as Andrei Ilyich. Only…

“Now he’ll say something unpleasant,” Bobrov thought.

Only, he says, it’s not good that you withdraw so much from society and give the impression of a closed person. You won’t understand who you really are, and you won’t know how to deal with you. Oh yes! - Svezhevsky suddenly slapped himself on the forehead. - I’m chatting, but I forgot to tell you the most important thing... The director asked everyone to be sure to be at the station tomorrow for the twelve o’clock train.

Will we meet anyone again?

Absolutely right. Guess who?

Svezhevsky's face took on a sly and triumphant expression. He rubbed his hands and seemed to experience great pleasure as he prepared to deliver the interesting news.

Really, I don’t know who... And I’m not even a master at guessing,” said Bobrov.

No, my dear, please guess... Well, at least name someone at random...

Bobrov fell silent and began to watch the actions of the steam crane with exaggerated attention. Svezhevsky noticed this and began to fuss even more than before.

You won’t say anything... Well, I won’t torment you anymore. They are waiting for Kvashnin himself.

He pronounced his surname with such open servility that Bobrov even felt disgusted.

What do you find particularly important here? - Andrei Ilyich asked casually.

Like “what’s special”? Have mercy. After all, he is on the board and does whatever he wants: they listen to him, like an oracle. And now: the board authorized him to speed up the work, that is, in other words, he authorized himself to do this. You will see what thunder and lightning we will have when he arrives. Last year he inspected the building - it seems that this was before you?.. So the director and four engineers flew to hell from their places. Will your blowout end soon?

Yes, it's almost ready.

It's good. With him, it means we will celebrate the opening and the beginning of stone work. Have you ever met Kvashnin himself?

Never. Of course, I heard the name...

And I had such pleasure. Well, I’ll tell you, this is the type you won’t see anymore. All of St. Petersburg knows him. Firstly, he is so fat that his hands do not meet on his stomach. Don't believe me? Honestly. He also has a special carriage, where the entire right side opens on hinges. Wherein enormous growth, red-haired, and a voice like the trumpet of Jericho. But what a clever girl! Oh, my God!.. He is a member of the board of all joint-stock companies... he receives two hundred thousand for just seven meetings a year! But when it is necessary to save the situation at general meetings, it is better not to find him. He will report the most dubious annual report in such a way that the shareholders will see black as white, and then they will no longer know how to express their gratitude to the board. The main thing is that he is never completely unfamiliar with the matter he is talking about, and he tackles it with aplomb. When you listen to him tomorrow, you will probably think that all his life he has done nothing but tinker around blast furnaces, and he understands as much about them as I do about the Sanskrit language.

Na-ra-ra-ra-ram! - Bobrov sang falsely and deliberately casually, turning away.

Well... what's better... Do you know how he receives people in St. Petersburg? He sits naked in the bathtub up to his neck, only his red head shines above the water, and listens. And some secret councilor stands, bending respectfully before him, and reports... He is a terrible glutton... and he really knows how to eat; in all the best restaurants, cue balls are known "la Kvashnin. And don’t even talk about the woman. Three years ago, a comical incident happened to him...

And, seeing that Bobrov was about to leave, Svezhevsky grabbed him by the button and whispered imploringly:

Excuse me... this is so funny... excuse me, I will now... in a nutshell. You see how it was. In the fall, about three years ago, a poor young man came to St. Petersburg - an official, or something... I even know his last name, but I just can’t remember now. This young man is worried about a disputed inheritance and every morning, returning from official places, he goes into the Summer Garden to sit on a bench for a quarter of an hour... Well, okay. He sits for three days, four, five and notices that every day a red-haired gentleman of extraordinary thickness walks with him in the garden... They become acquainted. Red, who turns out to be Kvashnin, finds out from young man all his circumstances, takes part in it, regrets... However, he does not tell him his last name. Well, okay. Finally, one day the red-haired man suggests to the young man: “What, would you agree to marry one person, but with the agreement that immediately after the wedding you will separate from her and never see each other again?” And just at that time the young man was almost dying of hunger. “I agree,” he says, “only depending on what the reward is, and the money is up front.” Note that the young man also knows which end of the asparagus is eaten from. Well, ok... They came to an agreement. A week later, the red-haired man dresses the young man in a tailcoat and at first light takes him somewhere out of town, to church. There are no people; the bride is already waiting, all wrapped in a veil, but it is clear that she is pretty and very young. The wedding begins. Only the young man notices that his bride is standing somewhat sad. He asks her in a whisper: “It seems you came here against your will?” And she says: “Yes, and you, too, it seems?” So they explained to each other. It turns out that the girl was forced to marry by her own mother. Still, my conscience prevented me from directly giving Kvashnin’s daughter to my mother... Well, ok... They stand there and stand... the young man says: “Let’s get this thing out of the way: you and I are both young, there’s still more ahead for us.” there can be a lot of good things, let’s leave Kvashnin on the beans.” The girl is determined and quick-thinking. “Okay, he says, let’s do it.” The wedding is over, everyone is leaving the church, Kvashnin is beaming. And the young man even received money from him in advance, and quite a lot of money, because Kvashnin in these cases will not stand behind any capital. He approaches the young people and congratulates them, with the most ironic look. They listen to him, thank him, call him daddy, and suddenly they both jump into the stroller. "What's happened? Where?" - “How where? To the station for a wedding trip. Coachman, let's go!..” So Vasily Terentyevich remained in place with his mouth open... And then one day... What is this? Are you leaving already, Andrei Ilyich? - Svezhevsky interrupted his chatter, seeing that Bobrov, with a decisive look, was adjusting his hat on his head and fastening the buttons of his coat.

Sorry, I don’t have time,” Bobrov answered dryly. - As for your anecdote, I heard or read it somewhere before... My respect.

And, turning his back to Svezhevsky, puzzled by his abruptness, he quickly left the workshop.

III

Returning from the factory and having a quick lunch, Bobrov went out onto the porch. The coachman Mitrofan, who had previously received orders to saddle Farvater, a bay Don horse, was tightening the girth of the English saddle with effort. Fairvater inflated his stomach and quickly bent his neck several times, catching the sleeve of Mitrofan’s shirt with his teeth. Then Mitrofan shouted at him in an angry and unnatural bass voice: “But-oh! Pamper, idol! - and added, groaning from tension: “Look, you animal.”

Fairvater - a stallion of medium height, with a massive chest, a long body and a lean, slightly drooping rear - stood easily and slenderly on strong, hairy legs, with reliable hooves and a thin pastern. A connoisseur would be dissatisfied with his hook-nosed muzzle and long neck with a sharp, prominent Adam's apple. But Bobrov found that these features, characteristic of every Don horse, make up the beauty of Fairvater, just like the crooked legs of a dachshund and long ears at the setter. But in the entire factory there was no horse that could outrun Fairvater.

Although Mitrofan considered it necessary, like any good Russian coachman, to treat the horse harshly, not at all allowing either himself or it any manifestations of tenderness, and therefore called it “convict”, and “carrion”, and “murderer”, and even a “hamlet,” nevertheless, deep down in his soul he passionately loved Fairvater. This love was expressed in the fact that the Don stallion was better groomed and received more oats than Bobrov’s other state-owned horses: Lastochka and Chernomorets.

Did you give him something to drink, Mitrofan? - asked Bobrov.

Mitrofan did not answer immediately. He also had another habit of a good coachman - slowness and sedateness in conversation.

Give me a drink, Andrei Ilyich, how could I not give you a drink? But look around, you devil! I'll give you a face! - he shouted angrily at the horse. - Passion, master, how he wants to go under saddle today. Can not wait to.

As soon as Bobrov approached the Fairway and, taking the reins in his left hand, wrapped the mane around his fingers, a story began that repeated itself almost daily. The fairway, which had long been leering with a big angry eye at the approaching Bobrov, began to dance in place, arching its neck and throwing clods of dirt with its hind legs. Bobrov was jumping around him on one leg, trying to get his foot into the stirrup.

Let go, let go, the reins, Mitrofan! - he shouted, finally catching the stirrup, and at the same moment, throwing his leg over the croup, he found himself in the saddle.

Feeling the rider's legs. The fairway immediately relented and, having changed legs several times, snorting and shaking his head, he took off from the gate with a wide, elastic gallop...

The fast ride, the cold wind whistling in his ears, the fresh smell of an autumn, slightly wet field very soon calmed and revived Bobrov's sluggish nerves. In addition, every time he went to the Zinenki, he experienced a pleasant and anxious uplift of spirit.

The Zinenok family consisted of a father, mother and five daughters. My father worked at a factory and was in charge of a warehouse. This lazy and good-natured giant in appearance was in fact a very sneaky and tricky gentleman. He belonged to those people who, under the guise of saying something to everyone’s face, “ true truth“They rudely but pleasantly flatter their superiors, openly snitch on their colleagues, and treat their subordinates in the most outrageously despotic manner. He argued over every trifle, not listening to objections and shouting hoarsely; he loved to eat and had a weakness for Little Russian choral singing, and was invariably out of tune. Unbeknownst to himself, he was under the shoe of his wife, a short woman, sickly and cutesy, with tiny gray eyes set ridiculously close to her nose.

The daughters' names were: Maka, Beta, Shurochka, Nina and Kasya.

Each of them in the family was assigned its own role; Maka, a girl with a fish profile, enjoyed a reputation of an angelic character. “This Maka is simplicity itself.” - her parents said about her when she faded into the background during walks and evenings in the interests of her younger sisters (Maka was already over thirty).

Beta was considered smart, wore pince-nez and, as they said, even wanted to enroll in courses someday. She kept her head tilted to one side and down, like an old harness, and walked with a diving gait, rising and falling with each step. She pestered new guests with arguments about how women were better and more honest than men, or asked with naive playfulness: “You are so insightful... well, determine my character.” When the conversation turned to one of the classic household topics: “Who is taller: Lermontov or Pushkin?” or: “Does nature help to soften morals?” - Beta was pushed forward like a war elephant.

The third daughter, Shurochka, chose to specialize in playing fools with all the single engineers in turn. As soon as she found out that her old partner was going to get married, she, suppressing her grief and annoyance, chose a new one. Of course, the game was played with cute jokes and small captivating trickery, with the partner being called “nasty” and being hit on the hands with cards.

Nina was considered a common favorite in the family, a spoiled but lovely child. She was the outcast among her sisters, with their massive figures and rough, vulgar faces. Perhaps only Madame Zinenko could satisfactorily explain where Ninochka got this delicate, fragile figure, these almost aristocratic hands, a pretty dark face, covered in moles, small pink ears and lush, thin, slightly curly hair. Her parents placed it on her big hopes, and therefore she was allowed everything: to overeat on sweets, to burr cutely, and even to dress better than her sisters.

The youngest, Kasya, recently turned fourteen years old, but this phenomenal child has outgrown her mother by a head, far surpassing her older sisters in the powerful relief of her forms. Her figure has long attracted the gaze of factory youth, who, due to their remoteness from the city, are completely deprived of sorority, and Kasia accepted these glances with the naive shamelessness of a precociously matured girl.

This division of family charms was well known at the plant, and one joker once said that if you were to marry the Zinenki, then you would certainly marry all five of them at once. Engineers and student trainees looked at Zinenko's house as if it were a hotel, crowded there from morning to night, ate a lot, drank even more, but with amazing dexterity they avoided marriage networks.

Bobrov was not liked in this family. The petty-bourgeois tastes of Madame Zinenko, who sought to bring everything under the line of vulgar and happily boring provincial decency, were offended by Andrei Ilyich’s behavior. His bilious witticisms, when he was in the spirit, were met with widespread with open eyes, and, conversely, when he was silent for whole evenings, due to fatigue and irritation, he was suspected of secrecy, pride, silent irony, even oh! This was the most terrible thing! - they even suspected that he “wrote stories for magazines and collected types for them.”

Bobrov felt this mute enmity, expressed in carelessness at the table, in the surprised shrug of the shoulders of the mother of the family, but still continued to visit the Zinenoks. Did he love Nina? He couldn't answer that himself. When he had not been in their house for three or four days, the memory of her made his heart beat with sweet and anxious sadness. He imagined her slender, graceful figure, the smile of her languid, shadowed eyes, and the smell of her body, which for some reason reminded him of the smell of young sticky poplar buds.

But as soon as he visited the Zinenkas three evenings in a row, their company, their phrases began to tire him, always the same in the same cases, the stereotyped and unnatural expressions of their faces. Between the five “young ladies” and the “gentlemen” who “courted” them (Zinenkov’s everyday words), a vulgar and playful relationship was established once and for all. Both pretended that they constituted two warring camps. Every now and then one of the gentlemen, jokingly, stole some thing from the young lady and assured that he would not give it back; the young ladies sulked, whispered among themselves, called the joker “nasty” and laughed all the time with a wooden, loud, unpleasant laugh. And this was repeated every day, today in exactly the same words and with the same gestures as yesterday. Bobrov returned from Zinenki with a headache and with nerves tired from their provincial hassle.

Thus, in Bobrov’s soul there alternated longing for Nina, for the nervous squeeze of her always hot hands, with disgust for the boredom and mannerisms of her family. There were moments when he was completely preparing to propose to her. Then he would not be stopped even by the knowledge that she, with her coquetry of bad taste and spiritual emptiness, would make hell out of family life, that he and she think and speak in different languages. But he did not dare and was silent.

Now, approaching Shepetovka, he already knew in advance what and how they would say there in this or that case, he even imagined the expression on their faces. He knew that when they saw him on horseback from their terrace, a long argument would first arise between the young ladies, who were always on the lookout for “pleasant gentlemen,” about who was riding. When he gets closer, the one who guessed will start jumping up, clapping her hands, clicking her tongue and fervently shouting: “What? And what? I guessed right, I guessed right!” After that, she will run to Anna Afanasyevna: “Mom, Bobrov is coming, I was the first to guess!” And mother, lazily rubbing the tea cups, will turn to Nina - certainly to Nina - in such a tone as if she were conveying something funny and unexpected: “Ninochka, you know, Bobrov is coming.” And after that, all of them together will be extremely and very loudly amazed when they see Andrei Ilyich entering.

IV

The fairway walked, snorting loudly and questioning the reins. The Shepetovskaya economy house appeared in the distance. Its white walls and red roof were barely visible from the dense greenery of lilacs and acacias. Beneath the mountain, a small pond rose convexly from the green banks that surrounded it.

stood on the porch female figure. From a distance, Bobrov recognized her as Nina by her bright yellow blouse, which so beautifully set off the dark complexion of her face, and immediately, pulling Farvater’s reins, he straightened up and freed his toes, which had gotten far into the stirrups.

Have you come with your treasure again? Well, I just can’t see this freak! - Nina shouted from the porch in the cheerful and capricious voice of a spoiled child. She had long been in the habit of teasing Bobrov about his horse, to which he was so attached. In general, in the Zinenok house they were always teasing someone with something.

Throwing the reins to the running groom, Bobrov patted the horse’s steep neck, darkened with sweat, and followed Nina into the living room. Anna Afanasyevna, sitting at the samovar, pretended to be unusually amazed by Bobrov’s arrival.

Ah-ah-ah! Andrey Ilyich! Finally, you have come to us!.. - she exclaimed in a sing-song voice.

And, poking his hand right in the lips when he greeted her, she asked in her loud nasal voice:

Tea? Milk? Yablokov? Say what you want.

Merci, Anna Afanasyevna.

Merci - oui, ou merci - non?

Such French phrases were unchanged in the Zinenko family. Bobrov refused everything.

Well, then go to the terrace, the young people there are up to some kind of forfeits, or something, Madame Zinenko graciously allowed.

When he went out onto the balcony, all four young ladies exclaimed at once, in exactly the same tone and in the same nasal manner as their mother:

They played “the lady sent a hundred rubles”, “opinions” and some other game that the lisping Kasya called “playing posuda”. Among the guests were: three student trainees, who all the time stuck out their chests and took plastic poses, putting their legs forward and putting their hand in the back pocket of their coat; there was the technician Miller, distinguished by his beauty, stupidity and wonderful baritone, and, finally, some silent gentleman in gray, who did not attract anyone’s attention.

The game wasn't going well. The men performed their forfeits with a condescending and bored look: the girls refused them altogether, whispered to each other and laughed intensely.

It was getting dark. A huge red moon slowly appeared from behind the roofs of the nearby Village.

Children, go to your rooms! - Anna Afanasyevna shouted from the dining room. Ask Miller to sing something for us.

We had a lot of fun,” they chirped around their mother, “we laughed so much, laughed so much...

Only Nina and Bobrov remained on the balcony. She sat on the railing, clasping the post with her left hand and pressing herself against it in an unconsciously graceful pose. Bobrov sat on a low garden bench at her very feet and, looking up into her face, saw the delicate contours of her neck and chin.

Well, tell me something interesting, Andrei Ilyich,” Nina ordered impatiently.

Really, I don’t know what to tell you,” Bobrov objected. - It's terribly difficult to speak to order. I’m already thinking: is there such a conversational collection on different topics...

Eww! How boring you are,” Nina drawled. - Tell me, when are you in the spirit?

Tell me, why are you so afraid of silence? As soon as the conversation has dried up a little, you no longer feel at ease... Is it bad to talk in silence?

“We will be silent with you, willows...” Nina sang mockingly.

Of course, we will remain silent. Look: the sky is clear, the moon is red and huge, it’s so quiet on the balcony... What else?..

“And this stupid moon in this stupid sky,” Nina recited. - A propos, have you heard that Zinochka Markova is marrying Protopopov? It turns out! This Protopopov is an amazing man. - She shrugged. Zina refused him three times, but he still couldn’t calm down and proposed for the fourth time. And let him blame himself. She may respect him, but never love him!

These words were enough to stir the bile in Bobrov’s soul. He was always infuriated by Zinenok’s narrow, bourgeois vocabulary, with expressions like: “She loves him, but doesn’t respect him,” “She respects him, but doesn’t love him.” In their concepts these words were the only difficult relationships between a man and a woman, just as they had only two expressions to determine the moral, mental and physical characteristics of any person; "brunette" and "blonde".

And Bobrov, out of a vague desire to stir up his anger, asked:

What is this Protopopov like?

Protopopov? - Nina thought for a second. - He... how should I tell you... quite tall... brown-haired!..

And nothing more?

What else? Oh yes: he serves in the excise department...

But only? Really, Nina Grigorievna, you can’t find anything to characterize a person except that he is brown-haired and serves in the excise department! Think: how many interesting, talented and smart people. Is it really all just “brown-haired people” and “excise officials”? Look with what greedy curiosity peasant children observe life and how accurate they are in their judgments. And you, an intelligent and sensitive girl, pass by everything indifferently, because you have a dozen stock phrases in stock. I know that if someone mentions the moon in a conversation, you will immediately interject: “Like that stupid moon,” and so on. If I tell you, let's say, something out of the ordinary ordinary case, I know in advance that you will notice: “The legend is fresh, but hard to believe.” And so in everything, in everything... Believe me, for God’s sake, that everything is original, unique...

He fell silent with a bitter feeling in his mouth, and they both sat quietly and without moving for about five minutes. Suddenly, sonorous chords were heard from the living room, and Miller’s slightly touched, but full of deep expression, voice sang:

In the middle of a noisy ball, by chance,

In the anxiety of worldly vanity,

I saw you, but it's a mystery

Your features are covered.

Bobrov's embittered mood quickly subsided, and he now regretted that he had upset Nina. “Why did I decide to demand original courage from her naive, fresh, childish mind? - he thought. “After all, she’s like a bird: she chirps the first thing that comes to her mind, and, who knows, maybe this chirping is even much better than talking about emancipation, and about Nietzsche, and about the decadents?”

Nina Grigorievna, don’t be angry with me. “I got carried away and said something stupid,” he said in a low voice.

Nina was silent, turning away from him and looking at the rising moon. He found her dangling hand in the darkness and, shaking it gently, whispered:

Nina Grigorievna... Please...

Nina suddenly quickly turned to him and, responding to his squeeze with a quick, nervous squeeze, exclaimed in a tone of forgiveness and reproach:

You mean girl! You always offend me... You take advantage of the fact that I don’t know how to be angry with you!..

And, pushing away his suddenly trembling hand, almost breaking away from him, she ran across the balcony and disappeared through the door.

...And I sleep in unknown dreams...

Do I love you - I don't know

But it seems to me that I love...

Miller sang with a passionate and wistful expression.

“But it seems to me that I love you!” - Bobrov repeated in an excited whisper, taking a deep breath and pressing his hand to his beating heart.

“Why,” he thought touched, “do I tire myself with fruitless dreams of some unknown, sublime happiness, when here, near me, is simple but deep happiness? What else do you need from a woman, from a wife, if she has so much tenderness, meekness, grace and attention? We, poor, nervous, sick people, do not know how to simply take from life its joys, we deliberately poison them with the poison of our tireless need to delve into every feeling, in every thought of ourselves and others... Quiet night, the closeness of your beloved girl, sweet, simple speeches, a momentary outburst of anger and then a sudden caress - oh my God! Isn’t that the beauty of existence?”

He entered the living room cheerful, cheerful, almost triumphant. His eyes met Nina’s eyes, and in her long gaze he read a tender answer to his thoughts. “She will be my wife,” Bobrov thought, feeling calm joy in his soul.

The conversation was about Kvashnin. Anna Afanasyevna, filling the whole room with her confident voice, said that she was thinking of taking “her girls” to the station tomorrow too.

It may very well be that Vasily Terentyevich will want to pay us a visit. At least my husband’s niece wrote to me about his arrival a month ago cousin- Liza Belokonskaya...

This seems to be the Belokonskaya whose brother is married to Princess Mukhovetskaya? Mr. Zinenko dutifully inserted a memorized remark.

Well, yes, the same one,” Anna Afanasyevna condescendingly nodded her head in his direction. “She is also distantly related through her grandmother to the Stremoukhovs, whom you know.” And so Liza Belokonskaya wrote to me that she met Vasily Terentyevich in the same society and recommended that he visit us if he ever decided to go to the plant.

Will we be able to accept, Nyusya? - Zinenko asked worriedly.

How funny you say! We'll do what we can. After all, in any case, we won’t surprise anything with a person who has three hundred thousand in annual income.

God! Three hundred thousand! - Zinenko groaned. - It's just scary to think about.

Three hundred thousand! - Nina sighed, like an echo.

Three hundred thousand! - the girls exclaimed enthusiastically in unison.

Yes, and he lives it all down to the penny,” said Anna Afanasyevna. Then, answering the unspoken thought of her daughters, she added: “A married man.” Only, they say, he married very unsuccessfully. His wife is a kind of colorless person and not at all personable. Whatever you say, a wife should be a sign in her husband’s affairs.

Three hundred thousand! - Nina repeated again, as if delirious. - What can you do with this money!..

Anna Afanasyevna ran her hand over her voluminous hair.

If only you had such a husband, my dear. A?

These three hundred thousand of someone else's annual income definitely electrified the whole society. With shining eyes and flushed faces, they told and listened to anecdotes about the lives of millionaires, stories about fabulous dinner menus, magnificent horses, balls and historically crazy spending of money.

Bobrov's heart grew cold and sank painfully. He quietly found his hat and carefully walked out onto the porch. However, no one would have noticed his departure anyway.

And when he rode home at a fast trot and imagined Nina’s languid, dreamy eyes, whispering almost in oblivion: “Three hundred thousand!” - he suddenly remembered Svezhevsky’s morning joke.

This one... will also be able to sell itself! - he whispered, clenching his teeth convulsively and furiously hitting Farvater on the neck with his whip.

V

Approaching his apartment, Bobrov noticed light in the windows. “The doctor must have arrived without me and is now lying on the sofa waiting for my arrival,” he thought, restraining his lathered horse. In Bobrov's current mood, Dr. Goldberg was the only person whose presence he could endure without painful irritation.

He sincerely loved this carefree, meek Jew for his versatile mind, youthful liveliness of character and good-natured passion for abstract disputes. Whatever question Bobrov raised, Dr. Goldberg objected to him with the same interest in the matter and with invariable vehemence. And although only contradictions had so far arisen between both of them in their endless disputes, nevertheless they missed each other and saw each other almost every day.

The doctor was actually lying on the sofa, his legs thrown over the back, and reading some kind of brochure, holding it close to his myopic eyes. Quickly glancing over the spine, Bobrov recognized Mevius’s “Training Course in Metallurgy” and smiled. He knew well the doctor's habit of reading with equal enthusiasm, and certainly from the middle, everything that came to his hand.

“And I took care of the tea without you,” said the doctor, throwing the book aside and looking over his glasses at Bobrov. - Well, how are you jumping, my lord Andrei Ilyich? Ooh, how angry you are! What? Cheerful melancholy again?

“Ah, doctor, it’s a bad life to live in the world,” Bobrov said wearily.

Why is this so, my dear?

Yes, so... in general... everything is bad. Well, doctor, how is your hospital?

Our hospital is fine... alive. Today there was a very interesting surgical case. By God, it’s both funny and touching. Imagine, a guy from Masala masons comes for a morning inspection. These Masala guys, no matter what, are all heroes, “What do you want?” - I ask. “Well, Mr. Doctor, I was cutting bread for the artel, so I spoiled my finger, I can’t get the ore.” I examined his hand: it was a so-so scratch, nothing, but it had festered a little; I ordered the paramedic to put on a bandage. I just see that my boyfriend is not leaving. “Well, what else do you want? They glued your hand and go.” “That’s right,” he says, “they sealed it up, God bless you, but it’s just that I’m shaking my head, so I think, at the same time, you’ll give me something on the other side of my head.” “What’s wrong with your head? Someone cracked it, right?” The guy was so happy and laughed. “There is, he says, that sin. Having come to our senses, on the Savior (this means three days ago), we had a party with the gang and drank a bucket and a half of wine, well, the guys began to indulge among themselves... Well, me too. And after... can you figure something out in a fight? I began to examine the “bully”, and what do you think? - I was absolutely horrified! The skull was broken through, the hole was the size of a copper nickel, and fragments of bone were embedded in the brain... Now he lies unconscious in the hospital. Amazing, I tell you, people: babies and heroes at the same time. By God, I seriously think that only a patient Russian man will endure such repairs to the bulldozer. Another would have given up the ghost without moving. And then, what naive kindness: “Can you figure something out in a fight?” The devil knows what it is!

Bobrov walked back and forth around the room, cracking his riding crop at the tops of his high boots and absentmindedly listened to the doctor. The bitterness that had settled in his soul while still at Zinenki still could not calm down.

The doctor was silent for a while and, seeing that his interlocutor was not in the mood for conversation, said with sympathy:

You know what, Andrei Ilyich? Let's try to go to bed for a minute and grab a spoon or two of bromine for the night. It is good for your mood, but there will be no harm anyway...

They both lay down in the same room: Bobrov on the bed, the doctor on the same sofa. But neither of them could sleep. Goldberg listened for a long time in the darkness as Bobrov tossed from side to side and sighed, and finally he was the first to speak:

Well, what are you, darling? Well, why are you tormented? It’s better to tell me directly, what is it that has stuck in you? Everything will be easier. Tea, after all, I’m not a stranger to you, I’m not asking out of idle curiosity.

These simple words touched Bobrov. Although he and the doctor had almost friendly relations, neither of them had yet confirmed this out loud: both were sensitive people and were afraid of the prickly shame of mutual confessions. The doctor was the first to open his heart. The darkness of the night and pity for Andrei Ilyich helped this.

Everything is hard and disgusting for me. Osip Osipovich,” Bobrov responded quietly. First, it disgusts me that I work at a factory and get a lot of money for it, but this factory work is disgusting and disgusting to me! I consider myself an honest man and therefore I ask myself directly: “What are you doing? Who are you benefiting?" I am beginning to understand these issues and see that thanks to my labors, a hundred French rentier shopkeepers and a dozen clever Russian swindlers will eventually put millions into their pockets. And there is no other goal, no other meaning in that work, in preparation for which I killed the better half of my life!..

Well, this is even funny, Andrei Ilyich,” the doctor objected, turning in the darkness to face Bobrov. - You demand that some bourgeois be imbued with the interests of humanity. Since then, my dear, as the world stands, everything moves forward on its belly, it has not been and will not be otherwise. But the point is that you don’t care about the bourgeoisie, because you are much higher than them. Are you not content with the courageous and proud consciousness that you are pushing forward, in the language of editorials, the “chariot of progress”? Damn it! Shares in shipping companies bring colossal dividends, but does this prevent Fulton from being considered a benefactor of humanity?

Ah, doctor, doctor! - Bobrov winced in annoyance. “It seems you weren’t at Zinenok’s today, and suddenly they spoke through your lips.” worldly wisdom. Thank God I won't have to go far to argue, because I'm about to crush you with your favorite theory.

That is, what kind of theory is this?.. Excuse me... I don’t remember any theory... really, my dear, I don’t remember... I forgot something...

Forgot? And who, here, on this very sofa, foaming at the mouth, shouted that we, engineers and inventors, with our discoveries are accelerating the pulse of social life to a feverish speed? Who compared this life with the state of an animal imprisoned in a jar of oxygen? Oh, I remember very well what a terrible list of children of the twentieth century, neurasthenics, crazy, overworked, suicides, you threw in the eyes of these very benefactors of the human race. The telegraph, telephone, one hundred and twenty mile trains, you said, have reduced the distance to a minimum, - destroyed it... Time has risen in price to the point that they will soon begin to turn night into day, because the need for such a double life is already felt. A transaction that previously required whole months, now it ends in five minutes. But even this damn speed does not satisfy our impatience... Soon we will see each other along the wire at a distance of hundreds and thousands of miles!.. And yet, just fifty years ago, our ancestors, gathering from the village to the province , slowly served a prayer service and set off on the road with enough reserves for a polar expedition... And we rush headlong forward and forward, deafened by the roar and crackling of monstrous machines, stupefied by this mad rush, with irritated nerves, perverted tastes and thousands of new diseases... Remember, Doctor? These are all your own words, champion of beneficent progress!

The doctor, who had already tried in vain to object several times, took advantage of Bobrov’s momentary respite.

Well, yes, well, yes, my dear, I said all this,” he hurried, not quite confidently, however. - I still affirm this. But, my dear, you have to adapt, so to speak. How can we live differently? Every profession has these slippery little points. Take us, for example, doctors... Do you think we have all this as clear and good as in the book? But beyond surgery, we don’t know anything for sure. We invent new medicines and systems, but we completely forget that out of a thousand organisms, not two are at all similar in blood composition, heart activity, conditions of heredity and God knows what else! We have moved away from the one true therapeutic path - from the medicine of animals and healers, we have flooded the pharmacopoeia with various cocaine, atropines, phenacetins, but we have lost sight of what if to the common man give clean water Yes, assure him well that this is a strong medicine, then a simple person will recover. Meanwhile, in ninety cases out of a hundred, only this confidence inspired by our professional priestly aplomb helps in our practice. Will you believe it? One good doctor, and at the same time smart and fair man, admitted to me that hunters treat dogs much more rationally than we treat people. There is only one remedy - sulfur color - it won’t do much harm, and sometimes it still helps... Isn’t it, my dear, a nice picture? And, however, we do what we can... It is impossible, my dear, otherwise: life requires compromises... Sometimes, even with your appearance of an all-knowing augur, you will still alleviate the suffering of your neighbor. And thanks for that.

Yes, compromises are compromises,” Bobrov objected in a gloomy tone, “but, however, today you extracted bones from the skull of a Masala mason...

Oh, my dear, what does one corrected skull mean? Think about how many mouths you feed and how many hands you give work to. Even in the history of Ilovaisky it is said that “Tsar Boris, wanting to gain the favor of the masses, undertook the construction of public buildings during the famine years.” Something like that... So you calculate what a colossal amount of benefit you...

At the last words, Bobrov seemed to be thrown up on the bed, and he quickly sat down on it, his bare legs dangling down.

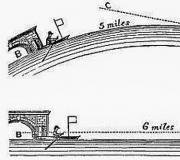

Benefits?! - he shouted frantically. -Are you telling me about the benefits? In this case, if we are to summarize the benefits and harms, then allow me to give you a small page from statistics. - And he began in a measured and sharp tone, as if speaking from the pulpit: - It has long been known that work in mines, mines, metal plants and large factories shortens the life of a worker by about a whole quarter. I'm not even talking about accidents or overwork. You, as a doctor, know much better than I what percentage is accounted for by syphilis, drunkenness and the monstrous conditions of vegetation in these damned barracks and dugouts... Wait, doctor, before you object, remember how many workers you have seen in factories over forty - forty five years? I haven't met it positively. In other words, this means that the worker gives the employer three months of his life per year, a week per month, or, in short, six hours per day. Now listen further... We, with six blast furnaces, will employ up to thirty thousand people - Tsar Boris probably never dreamed of such figures! Thirty thousand people, who all together, so to speak, burn one hundred and eighty thousand hours of their own lives per day, that is, seven and a half thousand days, that is, finally, how many years will it be?

About twenty years,” the doctor suggested after a short silence.

About twenty years a day! - Bobrov shouted. - Two days of work devours a whole person. Damn it! Do you remember from the Bible that some Assyrians or Moabites offered human sacrifices to their gods? But these copper gentlemen. Moloch and Dagon would blush with shame and resentment in front of the numbers that I just cited...

This peculiar mathematics just came to Bobrov’s head (he, like many very impressionable people, found new thoughts only in the midst of conversation). Nevertheless, both he and Goldberg were struck by the originality of the calculation.

Damn it, you stunned me,” the doctor responded from the sofa. - Although the numbers may not be entirely accurate...

“Do you know,” Bobrov continued with even greater fervor, do you know another statistical table, from which you can calculate with damn accuracy how many human lives each step forward of your devilish chariot, each invention of some filthy winnowing machine, seeder will cost? or rail rolling? Good, there is nothing to say, is your civilization if its fruits are counted in numbers, where an iron machine stands in the form of ones, and a whole series of human existences in the form of zeros!

But, listen, my dear,” the doctor objected, confused by Bobrov’s ardor, “then, in your opinion, it would be better to return to primitive labor, or what?” Why do you take all the black sides? After all, here we are, despite your mathematics, and there is a school at the factory, and a church, and a good hospital, and a society for cheap loans for workers...

Bobrov jumped out of bed and ran barefoot around the room.

And your hospital and school are all nothing! The children's tsatsa is a concession for humanists like you public opinion... If you want, I'll tell you how we really look... Do you know what the finish is?

Finish? This is something horsey, it seems? Something like this at the races?

Yes, at the races. The finish line is the last hundred fathoms before the milestone. The horse must gallop through them as quickly as possible - he may even die behind the post. The finish is a complete, maximum effort, and in order to squeeze the finish out of the horse, it is tortured with a whip until it bleeds... So here we are. And when the finish is squeezed out and the nag falls with a broken back and broken legs - to hell with her, she’s no good anymore! Then, if you please, console the nag who fell at the finish line with your schools and hospitals... Have you ever seen, doctor, the foundry and rolling business? If you have seen it, then you should know that it requires hellish strength of nerves, steel muscles and the dexterity of a circus performer... You should know that every master avoids mortal danger several times a day only thanks to the amazing presence of mind... And how much the worker receives for this work, do you want to know?

“And yet, as long as the plant stands, the work of this worker is guaranteed,” Goldberg said stubbornly.

Doctor, don't say naive things! - Bobrov exclaimed, sitting down on the windowsill. - Now the worker, more than ever, depends on market demand, on the stock exchange game, on various behind-the-scenes intrigues. Every huge enterprise, before it gets underway, has three or four dead patrons. Do you know how our society was created? Founded it with cash small company capitalists. The business was supposed to be arranged on a small scale at first. But a whole gang of engineers, directors and contractors stole the capital so quickly that the entrepreneurs did not even have time to look back. Huge buildings were erected, which later turned out to be unusable... Capital buildings were, as we say, “for meat,” that is, they were torn apart with dynamite. And when in the end the enterprise sold for ten kopecks per ruble, only then did it become clear that all this bastard acted according to a pre-thought-out system and received a certain salary from another, richer and more dexterous company for their vile way of acting. Now the business is on a much larger scale, but I am well aware that during the collapse of the first death, eight hundred workers did not receive two months' wages. Here's to secure work for you! Yes, as soon as stocks fall on the stock exchange, it immediately affects wages. I think you know how stocks rise and fall on the stock exchange? To do this, I need to come to St. Petersburg - whisper to the broker that, they say, I want to sell three thousand shares, “but, for God’s sake, this is between us, I’d better pay you a good price, just keep quiet...”. Then whisper the same thing to another and a third in confidence, and the shares instantly fall by several tens of rubles. And the bigger the secret, the sooner and more surely the shares will fall... Good security!..

Yes, at the races. The finish line is the last hundred fathoms before the milestone. The horse must gallop through them as quickly as possible - he may even die behind the post. The finish is a complete, maximum effort, and in order to squeeze the finish out of the horse, it is tortured with a whip until it bleeds... So here we are. And when the finish is squeezed out and the nag falls with a broken back and broken legs - to hell with her, she’s no good anymore! Then, if you please, console the nag who fell at the finish line with your schools and hospitals... Have you ever seen, doctor, the foundry and rolling business? If you have seen it, then you should know that it requires hellish strength of nerves, steel muscles and the dexterity of a circus performer... You should know that every master avoids mortal danger several times a day only thanks to the amazing presence of mind... And how much for this the worker receives labor, do you want to know?

“And yet, as long as the plant stands, the work of this worker is guaranteed,” Goldberg said stubbornly.

Doctor, don't say naive things! - Bobrov exclaimed, sitting down on the windowsill. - Now the worker, more than ever, depends on market demand, on the stock exchange game, on various behind-the-scenes intrigues. Every huge enterprise, before it gets underway, has three or four dead patrons. Do you know how our society was created? It was founded with cash by a small company of capitalists. The business was supposed to be arranged on a small scale at first. But a whole gang of engineers, directors and contractors stole the capital so quickly that the entrepreneurs did not even have time to look back. Huge buildings were erected, which later turned out to be unusable... Capital buildings were, as we say, “for meat,” that is, they were torn apart with dynamite. And when in the end the enterprise sold for ten kopecks per ruble, only then did it become clear that all this bastard acted according to a pre-thought-out system and received a certain salary from another, richer and more dexterous company for their vile way of acting. Now the business is on a much larger scale, but I am well aware that during the collapse of the first death, eight hundred workers did not receive two months' wages. Here's to secure work for you! Yes, as soon as stocks fall on the stock exchange, it immediately affects wages. I think you know how stocks rise and fall on the stock exchange? To do this, I need to come to St. Petersburg and whisper to the broker that I want to sell three hundred thousand shares, “but, for God’s sake, this is between us, I’d better pay you a good price, just keep quiet...” Then whisper the same thing to another and a third in confidence, and the shares instantly fall by several tens of rubles. And the bigger the secret, the sooner and more surely the shares will fall... Good security!..

With a strong movement of his hand, Bobrov opened the window at once. Cold air rushed into the room.

Look, look here, doctor! - Andrei Ilyich shouted, pointing his finger in the direction of the plant.

Goldberg propped himself up on his elbow and fixed his eyes on night darkness looking out the window. Throughout the vast expanse stretching out in the distance, countless piles of red-hot limestone glowed, scattered in countless numbers, on the surface of which bluish and green sulfur lights flashed every now and then... These were lime kilns burning 2. A huge red fluctuating glow stood over the plant. Against its bloody background, the dark tops of the tall pipes were harmoniously and clearly drawn, while their lower parts blurred in the gray fog coming from the ground. The gaping mouths of these giants continuously spewed out thick clouds of smoke, which mixed into one continuous, chaotic cloud slowly creeping to the east, in places white, like lumps of cotton wool, in others dirty gray, in others the yellowish color of iron rust. Above the thin, long chimneys, giving them the appearance of gigantic torches, bright sheaves of burning gas fluttered and rushed. From their uncertain reflection, the smoky cloud hanging over the plant, now flaring up, now extinguishing, took on strange and menacing shades. From time to time, when, at the sharp ringing of the signal hammer, the bell of the blast furnace was lowered, from its mouth, with a roar like distant thunder, a whole storm of flame and soot burst out to the very sky. Then, for a few moments, the entire plant emerged sharply and fearfully from the darkness, and the close row of black round cowpers seemed like the towers of a legendary iron castle. The lights of the coke ovens stretched out in long, regular rows. Sometimes one of them would suddenly flare up and glow, like a huge red eye. The electric lights mixed their bluish dead shine with the purple light of the red-hot iron... The incessant clanging and roar of iron rushed from there.

From the glow of the factory lights, Bobrov's face took on an ominous copper tint in the darkness, bright red highlights shone in his eyes, tangled hair fell haphazardly on his forehead. And his voice sounded shrill and angry,

Here he is - Moloch, demanding warm human blood! - Bobrov shouted, extending his thin hand out the window. - Oh, of course, there is progress here, machine labor, cultural successes... But think, for God’s sake - twenty years! Twenty years of human life per day!.. I swear to you, there are moments when I feel like a murderer!..

"God! But he’s crazy,” thought the doctor, who had goosebumps running down his back, and he began to calm Bobrov down.

Darling, Andrei Ilyich, leave it alone, my dear, why bother getting upset over stupid things. Look, the window is open, and it’s damp outside... Lie down, and put on your brow guard. “Manic, a complete maniac,” he thought, overwhelmed at the same time by pity and fear.

Bobrov resisted weakly, exhausted by the outbreak that had just passed. But when he got into bed, he suddenly burst into hysterical sobs. And for a long time the doctor sat next to him, stroking his head like a child, and telling him the first kind, soothing words that came his way.

Minimum (lat.).

Lime kilns are constructed in this way: a hill the size of a man is made of limestone and fired with wood or coal. This hill is heated for about a week until quicklime is formed from the stone. (Author's note.)

The next day, a solemn meeting of Vasily Terentyevich Kvashnin took place at the Ivankovo station. By eleven o'clock the entire factory management had gathered there. No one seemed to feel at ease. The director - Sergei Valeryanovich Shelkovnikov - drank glass after glass of seltzer water, took out his watch every minute and, without having time to look at the dial, immediately mechanically hid it in his pocket. Only this absent-minded movement betrayed his anxiety. The director's face - the beautiful, sleek, self-confident face of a socialite - remained motionless. Only a very few knew that Shelkovnikov was only officially, on paper, listed as the director of the building. All affairs were essentially handled by the Belgian engineer Andrea?, half-Pole, half-Swedish by nationality, whose role at the plant could not be understood by the uninitiated. The offices of both directors were located next to each other and connected by a door. Shelkovnikov did not dare to put the resolution on any important paper without first checking the symbol made in pencil somewhere on the corner of the page by Andrea’s hand. In urgent cases, which excluded the possibility of a meeting, Shelkovnikov took on a preoccupied look and said to the petitioner in a casual tone:

Sorry... I really can’t spare a minute for you... I’m overwhelmed... Be kind enough to explain your case to Mr. Andrea, and he will then explain it to me in a separate note.

Andrea's services to the board were innumerable. The brilliantly fraudulent project of ruining the first company of entrepreneurs came entirely out of his head, and it was his firm but invisible hand that brought the intrigue to the end. His projects, distinguished by their amazing simplicity and harmony, were at the same time considered the last word in mining science. He spoke all European languages and - a rare occurrence among engineers - possessed, in addition to his specialty, a wide variety of knowledge.

Of all those gathered at the station, only this one man, with a consumptive figure and the face of an old monkey, retained his usual equanimity. He had arrived later than everyone else and was now slowly walking back and forth along the platform, with his hands elbow-deep in the pockets of his wide, saggy trousers and chewing his eternal cigar. His bright eyes, behind which one could feel the great mind of a scientist and the strong will of an adventurer, as always, looked motionless and indifferently from under swollen, tired eyelids.

No one was surprised by the arrival of the Zinenok family. For some reason, everyone has long been accustomed to considering them an integral part of factory life. The girls brought with them into the gloomy hall of the station, where it was both cold and boring, their strained animation and unnatural laughter. They were surrounded by younger engineers, tired of the long wait. The girls, immediately assuming their usual defensive position, began to pour out sweet, but long-bored naivety, left and right. Among her bustling daughters, Anna Afanasyevna, small, active, fussy, seemed like a restless mother hen.

Bobrov, tired, almost sick after yesterday's outbreak, sat alone in the corner of the station hall and smoked a lot. When the Zinenok family came in and sat down at the round table, chattering loudly, Andrei Ilyich simultaneously experienced two very vague feelings. On the one hand, he felt ashamed for what he thought was the tactless arrival of this family, and he felt a burning, depressing shame for the other. On the other hand, he was delighted to see Nina, flushed from her fast ride, with excited, sparkling eyes, very nicely dressed and, as always happens, much more beautiful than his imagination had pictured her. In his sick, tormented soul, an unbearable desire for tender, fragrant girlish love, a thirst for the familiar and soothing female caress suddenly ignited.

He looked for an opportunity to approach Nina, but she was always busy chatting with two mountain students who vied with each other to make her laugh. And she laughed, flashing her small white teeth, more flirtatious and cheerful than ever. However, two or three times she met Bobrov’s eyes, and he fancied a silent, but not hostile question in her slightly raised eyebrows.

A long bell rang on the platform, signaling the departure of the train from the nearest station. There was confusion among the engineers. Andrei Ilyich watched from his corner with a mockery on his lips as one and the same cowardly thought instantly took possession of these twenty-odd people, as their faces suddenly became serious and preoccupied, their hands with an involuntary quick movement ran over the buttons of their coats, ties and caps, their eyes turned towards the bell. Soon there was no one left in the hall.

Andrei Ilyich stepped onto the platform. The young ladies, abandoned by the men who occupied them, crowded helplessly near the doors, around Anna Afanasyevna. Nina turned around at Bobrov’s steady, persistent gaze and, as if guessing his desire to talk to her alone, went to meet him halfway.

Hello. Why are you so pale today? You are sick? - she asked, shaking his hand firmly and tenderly and looking into his eyes seriously and affectionately. - Why did you leave so early yesterday and didn’t even want to say goodbye? Angry about something?

“Yes and no,” Bobrov answered smiling. - No, because I have no right to be angry.

Let's assume that every person has the right to be angry. Especially if he knows that his opinion is valued. Why yes?

Because... You see, Nina Grigorievna,” said Bobrov, feeling a sudden surge of courage. - Yesterday, when you and I were sitting on the balcony, remember? - Thanks to you, I experienced several wonderful moments. And I realized that if you wanted, you could make me the happiest person in the world... Oh, why am I afraid and procrastinating... After all, you know, you guessed it, because you have long known that I ...

He didn’t finish... The courage that had surged through him suddenly disappeared.

What are you... what is it? - Nina asked with feigned indifference, but her voice suddenly, against her will, trembled, and lowered her eyes to the ground.

She was waiting for a declaration of love, which always so strongly and pleasantly excites the hearts of young girls, no matter whether their heart reciprocates this declaration or not. Her cheeks paled slightly.

Not now... later, someday,” Bobrov hesitated. “Someday, in a different situation, I’ll tell you this... For God’s sake, not now,” he added pleadingly.

(eng. Twig and Molochai) - insatiable... Zillaha. Twig higher Molochs and has sharp facial features, Moloch slightly lower, his...

And how much does the worker receive for this work, do you want to know?

“Still, as long as the plant stands, the work of this worker is guaranteed,” Goldberg said stubbornly.