The purpose of art is to give pleasure to my mother. Art as a source of pleasure

Which “duplicated” with artistic means what other spheres of human activity do in their own way (science, philosophy, futurology, pedagogy, QMS, hypnosis). Now we will talk about completely specific functions inherent only to art - aesthetic and hedonistic.

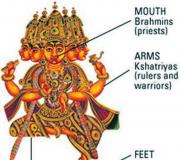

Even in ancient times, the importance of the aesthetic function of art was realized. The Indian poet Kalidasa (circa 5th century) identified four goals of art: to evoke the admiration of the gods; create images of the surrounding world and people; deliver high pleasure with the help of aesthetic feelings (races): comedy, love, compassion, fear, horror; serve as a source of pleasure, joy, happiness and beauty. Indian scientist V. Bahadur believes: the purpose of art is to inspire, to purify

and ennoble a person, for this it must be beautiful (Bahadur. 1956. R. 17).

Aesthetic function- irreplaceable specific ability of art:

1) shape artistic tastes, abilities and needs of a person. Before an artistically civilized consciousness, the world appears as aesthetically significant in every manifestation. Nature itself appears in the eyes of the poet as an aesthetic value, the universe becomes poetic, becomes a theatrical stage, a gallery, an artistic creation non finita (unfinished). Art gives people this sense of the aesthetic significance of the world;

2) value orientation of a person in the world(build value consciousness, teach to see life through the prism of imagery). Without value orientations, a person is even worse than without vision - he cannot understand how to relate to something, nor determine the priorities of activity, nor build a hierarchy of phenomena in the surrounding world;

3) awaken the creative spirit of the individual, the desire and ability to create according to the laws of beauty. Art brings out the artist in a person. This is not at all about awakening a passion for amateur artistic activity, but about human activity consistent with the internal measure of each object, that is, about mastering the world according to the laws of beauty. When making even purely utilitarian objects (a table, a chandelier, a car), a person cares about benefits, convenience, and beauty. According to the laws of beauty, everything that a person produces is created. And he needs a feeling of beauty.

Einstein noted the importance of art for spiritual life, and for the very process of scientific creativity. “For me personally, works of art give me a feeling of the highest happiness. In them I draw such spiritual bliss as in any other area... If you ask who arouses the greatest interest in me now, I will answer: Dostoevsky!.. Dostoevsky gives me more , than any scientific thinker, more than Gauss! (Cm.: Moshkovsky. 1922 P. 162).

To awaken in a person an artist who wants and knows how to create according to the laws of beauty - this goal of art will increase with the development of society.

Art is the instillation of a certain system of thoughts and feelings, an almost hypnotic effect on the subconscious and the entire human psyche. Often the work is literally mesmerizing. Suggestion (suggestive influence) was already inherent in primitive art. The Australian tribes, on the night before the battle, evoked a surge of courage with songs and dances. An ancient Greek legend tells: the Spartans, exhausted by a long war, turned to the Athenians for help, who, in mockery, sent the lame and frail musician Tyrtaeus instead of reinforcements. However, it turned out that this was the most effective help: Tyrtaeus raised the morale of the Spartans with his songs, and they defeated their enemies.

Understanding the experience of the artistic culture of his country, Indian researcher K.K. Pandey argues that suggestion always dominates in art. The main effect of folklore incantations, spells, and laments is suggestion.

Gothic temple architecture inspires the viewer with sacred awe of divine grandeur.

The inspiring role of art is clearly manifested in the marches, designed to instill cheerfulness in the marching columns of fighters. In the “hour of courage” (Akhmatova) in the life of the people, the inspiring function of art takes on a particularly important role. This was the case during the Great Patriotic War. One of the first foreign performers of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, Koussevitzky, remarked: “Not since Beethoven has there been a composer who could speak to the masses with such power of suggestion.” The focus on inspiring influence is also inherent in the lyrics of this period. This is, for example, Simonov’s popular poem “Wait for Me”:

Wait for me and I will come back,

Just wait a lot.

Wait when they make you sad

Yellow rains,

Wait for the snow to blow

Wait for it to be hot

Wait when others are not waiting,

Forgetting yesterday.

Wait when from distant places

No letters will arrive

Wait until you get bored

To everyone who is waiting together.

In twelve lines, the word “wait” is repeated eight times like a spell. All the semantic meaning of this repetition, all its inspiring magic are formulated in the finale of the poem:

Those who were not waiting for them cannot understand,

Like in the middle of fire

By your expectation

You saved me.

(Simonov. 1979. P. 158).

A poetic thought is expressed here that is important to millions of people separated by war. Soldiers sent these poems home or carried them close to their hearts in their tunic pockets. When Simonov expressed the same idea in a film script, the result was a mediocre work: it contained the same topical theme, but the magic of suggestion was lost.

I remember how Ehrenburg, in a conversation with students at the Literary Institute in 1945, expressed the opinion that the essence of poetry is in the spell. This, of course, is a narrowing of the possibilities of poetry. However, this is a characteristic misconception, dictated by a precise sense of the development trend of military poetry, which sought immediate effective intervention in spiritual life and therefore relied on folklore forms developed by the centuries-old artistic experience of the people, such as orders, vows, visions, dreams, conversations with the dead, appeals to rivers, cities. The vocabulary of spells, vows, blessings, anachronisms of ritual figures of speech are heard in the military poems of Tychina, Dolmatovsky, Isakovsky, Surkov. Thus, the folk, domestic character of the war against the invaders was manifested in the poetic style.

Suggestion is a function of art, close to educational, but not coinciding with it: education is a long process, suggestion is one-time. During tense periods of history, the suggestive function plays a large, sometimes even leading role in the overall system of functions of art.

10. Specific function – aesthetic

(art as the formation of a creative spirit and value orientations)

Until now, we have been talking about the functions of art, which “duplicated” with artistic means what other spheres of human activity do in their own way (science, philosophy, futurology, pedagogy, QMS, hypnosis). Now we will talk about completely specific functions inherent only to art - aesthetic and hedonistic.

Even in ancient times, the importance of the aesthetic function of art was realized. The Indian poet Kalidasa (circa 5th century) identified four goals of art: to evoke the admiration of the gods; create images of the surrounding world and people; deliver high pleasure with the help of aesthetic feelings (races): comedy, love, compassion, fear, horror; serve as a source of pleasure, joy, happiness and beauty. Indian scientist V. Bahadur believes: the purpose of art is to inspire, purify and ennoble a person, for this it must be beautiful (Bahadur. 1956. P. 17).

The aesthetic function is an irreplaceable specific ability of art:

1) to form artistic tastes, abilities and needs of a person. Before an artistically civilized consciousness, the world appears as aesthetically significant in every manifestation. Nature itself appears in the eyes of the poet as an aesthetic value, the universe becomes poetic, becomes a theatrical stage, a gallery, an artistic creation non finita (unfinished). Art gives people this sense of the aesthetic significance of the world;

2) value-orientate a person in the world (build a value consciousness, teach to see life through the prism of imagery). Without value orientations, a person is even worse off than without vision - he cannot understand how to relate to something, nor determine priorities for activity, nor build a hierarchy of phenomena in the surrounding world;

3) awaken the creative spirit of the individual, the desire and ability to create according to the laws of beauty. Art brings out the artist in a person. This is not at all about awakening a passion for amateur artistic activity, but about human activity consistent with the internal measure of each object, that is, about mastering the world according to the laws of beauty. When making even purely utilitarian objects (a table, a chandelier, a car), a person cares about benefits, convenience, and beauty. According to the laws of beauty, everything that a person produces is created. And he needs a feeling of beauty.

Einstein noted the importance of art for spiritual life, and for the very process of scientific creativity. “Personally, works of art give me a feeling of supreme happiness. In them I draw such spiritual bliss as in any other field... If you ask who is of the greatest interest to me now, I will answer: Dostoevsky!.. Dostoevsky gives me more than any scientific thinker, more than Gauss! » (see: Moshkovsky. 1922. P. 162).

To awaken in a person an artist who wants and knows how to create according to the laws of beauty - this goal of art will increase with the development of society.

The aesthetic function of art (the first essential function) ensures the socialization of the individual and shapes his creative activity; permeates all other functions of art.

11. Specific function – hedonic

(art as pleasure)

Art gives people pleasure and creates an eye capable of enjoying the beauty of colors and shapes, an ear capable of capturing the harmony of sounds. The hedonistic function (the second essential function), like the aesthetic one, permeates all other functions of art. Even the ancient Greeks noted the special, spiritual nature of aesthetic pleasure and distinguished it from carnal pleasures.

Prerequisites for the hedonistic function of art (sources of pleasure in a work of art): 1) the artist freely (= masterfully) masters vital material and the means of its artistic development; art is the sphere of freedom, mastery of the aesthetic wealth of the world; freedom (= mastery) is admired and enjoyable; 2) the artist correlates all mastered phenomena with humanity, revealing their aesthetic value; 3) in a work there is a harmonious unity of perfect artistic form and content, artistic creativity gives people the joy of comprehending artistic truth and beauty; 4) artistic reality is ordered and built according to the laws of beauty; 5) the recipient feels connected to the impulses of inspiration, to the poet’s creativity (the joy of co-creation); 6) artistic creativity has a playful aspect (art models human activity in a playful way); the play of free forces is another manifestation of freedom in art, which brings extraordinary joy. “The mood of the game is detachment and inspiration - sacred or simply festive, depending on whether the game is enlightenment or fun. The action itself is accompanied by feelings of uplift and tension and brings with it joy and release. The sphere of play includes all methods of poetic formation: the metrical and rhythmic division of spoken or sung speech, the precise use of rhyme and assonance, the disguise of meaning, the skillful construction of a phrase. And the one who, following Paul Valéry, calls poetry a game, a game in which words and speech are played, does not resort to metaphor, but captures the deepest meaning of the word “poetry” itself” (Hizinga. 1991, p. 80).

The hedonistic function of art is based on the idea of the intrinsic value of the individual. Art gives a person the disinterested joy of aesthetic pleasure. It is the self-valued personality that is ultimately the most socially effective. In other words, the self-worth of an individual is an essential aspect of his deep socialization, a factor of his creative activity.

Usually, the cognitive, educational, compensatory and communicative functions of art are distinguished.Art, along with science, primarily acts as one of the means of self-knowledge of society. Through the artistic model of the world, through the “second reality”, a deeper knowledge of the true natural and social reality is achieved.

Moreover, the ideal world of art, aimed at understanding human reality, is created with the help of special “building structures” - poetic words, melody, rhythm, drawing, plasticity of the human body and other aesthetic means, which often turn out to be more effective tools for understanding reality than concepts and judgments and theories applied by science. The high information content of art is due to the fact that its forms bring knowledge to people in an easily accessible form, in a playful form.

But if for science knowledge of the world is the main function, then for art this task is secondary. Its main function is aesthetic education. Art is intended not so much to educate a person as to elevate, ennoble, enlighten the soul, and awaken good feelings in him. The main goal of art is to, having created one or another ideal, a model of perfection, thereby formulate the spiritual prerequisites for the practical introduction of people to this ideal in their ordinary, everyday activities.

At the same time, art also solves simpler, more mundane problems. They perform an entertaining or compensatory function. Its necessity is due to the fact that the real life around us is quite harsh, often monotonous, and boring. As the poet said, “our planet is poorly equipped for fun.”

Art is precisely designed, by entertaining people with the help of books, operettas, comedies, television series, to help them overcome this severity and boredom of life. Of course, art cannot replace life, but it can complement it and increase interest in it.

And finally, art also performs a communicative function, promoting self-expression in the process of artistic activity not only of creators of artistic values, art professionals, but also of ordinary people - consumers of works of art.

It is these tasks and functions, in short, that testify to the high purpose of art and explain the reasons for its preservation and survival even in crisis periods of social development.

|

|

Very often, turning to some work of art, we involuntarily ask the question: for what? Why was this book written? What did the artist want to say with this painting? Why did this particular piece of music affect us so much?

For what purpose is a work of art created? It is known that no other species of animal except Homo sapiens can be a creator of art. After all, art goes beyond the simply useful; it satisfies other, higher human needs.

Of course, there is no single reason for creating different works of art - there are many reasons, as well as many interpretations.

According to the purpose of creation, works of art can be divided into motivated and unmotivated.

Unmotivated goals

You can often hear: “The soul sings!”, “The words themselves rush out!” and similar statements. What does this mean?

This means that the person has developed the need to express yourself, your feelings and thoughts. There are many ways of expression. Have you ever seen inscriptions on a tree (bench, wall) with approximately the following content: “Vanya was here” or “Seryozha + Tanya”? Of course we saw it! The man wanted so badly to express his feelings! You can, of course, express these same feelings in another way, for example, like this:

I remember a wonderful moment:

You appeared before me...

But... By the way, this is why children should be introduced to art from a very early age, so that their methods of self-expression will subsequently be more diverse.

Fortunately, there are people with a rich imagination and a deep inner world who can express their feelings and thoughts in such a way that they captivate other people, and not only captivate them, but also sometimes force them to reconsider their own inner world and their attitudes. Such works of art can be created by people in whose souls there is instinctively harmony, a sense of rhythm, which is akin to nature. But Albert Einstein believed that the purpose of art is desire for mystery, the ability to feel your connection with the Universe: “The most beautiful thing we can experience in life is mystery. It is the source of all true art or science." Well, it’s also impossible to disagree with this.

Leonardo da Vinci "Mona Lisa" ("La Gioconda")

And an example of this is the “Mona Lisa” (“La Gioconda”) by Leonardo da Vinci, whose mysterious smile still cannot be solved. “Soon it will be four centuries since the Mona Lisa deprives everyone of their sanity who, having seen enough of it, begins to talk about it,” he said about this with a bit of bitter irony at the end of the 19th century. Gruye.

Imagination, characteristic of man, is also an unmotivated function of art. What does this mean? It is not always possible to express in words what you feel. The Russian poet F. Tyutchev said this well:

How can the heart express itself?

How can someone else understand you?

Will he understand what you live for?

A spoken thought is a lie.

(F.I. Tyutchev “Silentium!”)

There is one more function of art, which is also its purpose: the opportunity to reach out to the whole world. After all, what is created (music, sculpture, poetry, etc.) is given to people.

Motivated goals

Everything is clear here: the work is created with a predetermined purpose. The purpose can be different, for example, pay attention to some phenomenon in society. It was for this purpose that the novel by L.N. was created. Tolstoy's "Resurrection".

L.N. Tolstoy

Sometimes an artist creates his work as aillustrations for a work by another author. And if he does it very well, then a new, unique work of another type of art appears. An example is the musical illustrations by G.V. Sviridov to the story by A.S. Pushkin "Blizzard".

G.V. Sviridov

Works of art can be created and for fun: for example, cartoons. Although, of course, a good cartoon not only entertains, but definitely conveys some useful emotions or thoughts to the audience.

At the beginning of the 20th century. Many unusual works were created, which were called avant-garde art. It identifies several directions (Dadaism, surrealism, constructivism, etc.), which we will discuss in more detail later. So the goal of avant-garde art was provoking political change, this art is assertive, uncompromising. Remember the poems of V. Mayakovsky.

It turns out that the purpose of art can even be human health improvement. In any case, this is what psychotherapists think, using music for relaxation and color and paint to influence the mental state of the individual. It’s not for nothing that they say that a word can kill, but it can also save.

There are words - like wounds, words - like judgment, -

They do not surrender and are not taken prisoner.

A word can kill, a word can save,

With a word you can lead the shelves with you.

In a word you can sell, and betray, and buy,

The word can be poured into striking lead.

(V. Shefner “Words”)

There is even art for social protest- This is the so-called street art, the most famous variety of which is graffiti art.

The main thing in street art is to involve the viewer in dialogue and show your program for seeing the world and thinking. But you have to be very careful here: graffiti can be illegal and constitute a form of vandalism if applied to buses, trains, house walls, bridges and other prominent places without permission.

And finally advertising. Can it be considered art? To some extent, yes, because although it is created with the goal of promoting a commercial product by creating a positive attitude towards it, it can be performed at a high artistic level.

All the functions of art that we have named can exist (and do exist) in interaction, i.e. You can, for example, entertain and at the same time secretly advertise something.

It should be noted that, unfortunately, one of the characteristic features of the art of the postmodern era (after the 1970s) is the growth of utilitarianism, the focus on commercialization, and unmotivated art becomes the lot of the elite. Why "Unfortunately"? Try to answer this question yourself.

By the way, let's talk about art for the elite. Now this expression has somewhat changed its meaning. Previously, the “chosen ones” were considered to be people of the upper class, rich, able to buy beautiful and sometimes useless things, prone to luxury. It was for such people that the Palace of Versailles or the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, with their extensive collections collected by the richest monarchs of Europe, were built. Only very rich people, governments or organizations can afford such collections. But, to the credit of many of these people, they then transferred the collections they collected to the state.

I. Kramskoy "Portrait of P. M. Tretyakov"

Here we cannot help but remember the Russian merchantPavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, founder of the State Tretyakov Gallery, or president of the regional railway networkJohn Taylor Johnston, whose personal collection of works of art formed the basis of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York). At that time, artists sought to ensure that access to works of art was open to everyone: for people of any social status and for children. Now this has become possible, but right now the masses do not really need art or need only utilitarian art. In this case, the “chosen ones” are already people who are interested in unmotivated art, which satisfies, as we said earlier, the highest human needs - the needs of the soul, heart and mind.

Purposes of art

In thinking about the purpose of art, in other words, in deciding the question of why people love art, trying hard to develop it, I am forced to turn to the experience of the only representative of humanity about whom I know something, namely, myself. When I think about what I strive for, I find only one word - happiness. I want to be happy while I live, because as for death, having never experienced it, I have no idea what it means, and therefore my mind cannot even come to terms with it. I know what it means to live, but I cannot guess what it means to die. So, I want to be happy, and sometimes, to tell the truth, even cheerful, and it is difficult for me to believe that such a desire is not universal. And everything that strives for happiness, I try to cultivate as much as I can. Moreover, when I further reflect on my life, I find that it seems to me to be under the influence of two dominant tendencies, which, for lack of better words, I must call the desire for activity and the desire for idleness. Now one thing, now another, but they always make themselves felt, demanding satisfaction. When I am possessed by the desire for activity, I must do something, otherwise the blues take over me and I feel uneasy. When the desire for idleness descends upon me, it becomes difficult for me if I cannot rest and allow my mind to wander among all kinds of pictures, pleasant or terrible, which are suggested either by my personal experience or by communication with the thoughts of other people, living or dead. And if circumstances do not allow me to indulge in this idleness, then at best I must go through torment until I manage to arouse energy so that it takes the place of idleness and makes me happy again. And if I have no way of arousing the energy so that it will fulfill its duty of restoring joy to me, and if I have to work despite the desire to do nothing, then I really feel miserable and would almost like to die, although I don’t know what such is death.

Moreover, I see that if in idleness I am entertained by memories, then when I surrender myself to the desire for activity, I am pleased with hope. This hope is sometimes great and serious, and sometimes empty, but without it beneficial energy cannot arise. And again I understand that if sometimes I can give vent to the desire to act, simply by applying it in work, the result of which lasts no more than the current hour - in the game, in short - then this desire is quickly exhausted, replaced by lethargy due to the fact that the hope associated with the work was negligible, if not barely felt at all. In general, in order to satisfy the desire that has taken hold of me, I must either do something or force myself to believe that I am doing something.

So I believe that these two aspirations predominate in the lives of all people in varying proportions and that this explains why people have always loved art and more or less diligently practiced it, otherwise why would they need to touch art and thus increase their work , which, whether they wanted it or not, they had to do in order to live? This probably gave them pleasure, because only in very developed civilizations is a person able to force others to work for himself so that he himself can create works of art, while all people who left some trace were involved in folk art.

No one, I believe, is inclined to deny that the purpose of art is to bring joy to a person whose feelings are ripe to perceive it. A work of art is created to make a person happier, to entertain him during hours of leisure or quiet, so that emptiness, this inevitable evil of such hours, gives way to pleasant contemplation, dreams, or whatever. And in this case, the energy and desire to work will not return to the person so quickly: he will want even newer and more subtle pleasures.

To calm anxiety is obviously one of the main goals of art. As far as I know, among the living there are gifted people whose only vice is imbalance, and this, apparently, is the only thing that prevents them from being happy. But this is enough. Imbalance is a flaw in their mental world. It turns them into unhappy people and bad citizens.

But, having agreed that bringing a person into mental balance is the most important task of art, let us ask at what cost we achieve it. I recognized that the pursuit of art has burdened humanity with additional labor, although I am convinced that this will not always be the case. And besides, having increased man's labor, has it also increased his suffering? There are always people who are ready to immediately answer this question in the affirmative. There were and are two types of people who do not love and despise art as shameful stupidity. In addition to the devout hermits who consider it a worldly obsession that prevents people from concentrating on thoughts of salvation or the death of the soul in another world, hermits who hate art because they think that it contributes to a person’s earthly happiness - besides them, there are also people who , considering the struggle of life from the most, in their opinion, reasonable point of view, they despise art, believing that it aggravates the slavery of man by increasing the burden of his labor. If this were the case, then, in my opinion, the question would remain unresolved: is it not worth enduring a new burden of labor for the sake of new additional joys in relaxation - recognizing, of course, universal equality. But the point is not at all, in my opinion, that practicing art aggravates our already burdensome work. No, on the contrary, I believe that if this were so, art would never have arisen at all and, of course, we would never have found it among peoples among whom civilization existed only in its infancy. In other words, I am convinced that art can never be the fruit of external coercion. The labor that creates it is voluntary and is partly undertaken for the sake of the labor itself, and partly in the hope of creating something that, when it appears, will give pleasure to the consumer. Or again, this additional labor - when it is in fact additional - is undertaken to give an outlet to energy, directing it towards the creation of something worthy and therefore capable of awakening in the worker, as he works, a living hope. It is probably difficult to explain to people lacking artistic sense that the work of a skilled artisan always gives a certain sensual pleasure when he performs it successfully, and this increases in proportion to the independence and individuality of his work. You must also understand that this kind of creativity and the pleasure derived from it is not limited to the creation of artistic works such as paintings, statues and the like, but in one form or another accompanies and should accompany all work. Only on this path will our energy find a way out.

Therefore, the purpose of art is to increase people’s happiness, filling their leisure time with beauty and interest in life, preventing them from getting tired even from rest, affirming hope in them and causing physical pleasure from work itself. In short, the purpose of art is to make a person’s work happy and his rest fruitful. And, therefore, true art is an unclouded blessing for the human race.

But since the word "authentic" has many meanings, I must ask permission to try to draw from my discussion about the purposes of art some practical conclusions, which, as I imagine and even hope, will cause controversy, since only superficial talk about art does not touch upon social problems that encourage all serious people to think. After all, art - whether it is rich or sterile, sincere or empty - is and should be an expression of the society in which it exists.

First of all, it is clear to me that at present the people who perceive the state of affairs most broadly and deeply are completely dissatisfied with the modern state of the arts, just as with the modern state of society. And I assert this, despite the imaginary revival of art that has taken place in recent years. Indeed, all this fuss about art among a section of the educated public of our day only shows how well-founded the above-mentioned dissatisfaction is. Forty years ago there was much less talk about art, much less activity in it than there is now. And this is especially true in relation to the art of architecture, which is what I am primarily going to talk about now. Since then, people have consciously sought to resurrect the spirit of the past in art, and outwardly things have been going well. Nevertheless, I must say that, in spite of these conscious efforts, forty years ago living in England for a person capable of feeling and understanding beauty was not so painful as it is now. And we, who understand the importance of art, know well, although we do not often dare to say it, that in forty years it will be even sadder to live here if we continue to follow the road we are walking now. About thirty years ago I first saw the city of Rouen (1), which at that time in its appearance was still a fragment of the Middle Ages. It is impossible to express in words how fascinated I was by the beauty, romance and spirit of bygone times hovering over it. Looking back on my past life, I can only say that seeing this city was the greatest pleasure I have ever experienced. And now, in the future, no one will experience such pleasure: it is lost to the world forever.

At that time I was finishing Oxford. Although not so amazing, not so romantic and at first glance not so medieval as that Norman city, Oxford still retained at that time much of its former charm, and the appearance of its then gloomy streets remained a source of inspiration and inspiration for me all my life. a joy that would be even deeper if I could only forget what these streets are now. All this could have been much more important to me than so-called training, although no one tried to teach me what I was talking about, and I myself did not strive to learn. Since then, the guardians of beauty and romance, so fertile for education, supposedly busy with “higher education” (that is the name of the sterile system of compromises that they follow), have completely ignored this beauty and romance and, instead of protecting them, have given them over to power commercial people and clearly intend to destroy them completely. Another joy of the world disappeared like smoke. Without the slightest benefit, without reason, in the most stupid way, beauty and romance are again thrown away.

I give these two examples simply because they stuck in my mind. They are typical of what is happening everywhere in the civilized world. The world is everywhere becoming uglier and more stereotyped, in spite of the conscious and very energetic efforts of a small group of people, efforts aimed at the revival of art and so clearly not coinciding with the trend of the century that, in while the uneducated have not heard anything about these efforts, the mass of the educated perceives them simply as a joke, which, however, is now even beginning to become boring.

If it is true, as I have argued, that true art is an unclouded good for the world, then all this is very serious, for at first glance it seems that soon there will be no art left in the world, which will thus lose its unclouded good. I don't think the world can really afford this.

For art, if it is destined to perish, has already exhausted itself and its purpose will soon be forgotten, and this purpose is to make work enjoyable and rest fruitful. Well, then any work should become joyless, and any rest - fruitless? Indeed, if art is destined to perish, then things will take just such a turn, unless something else comes to replace art - something that currently has no name and about which we have not yet even dreamed.

I don’t think that anything else will come instead of art, and not because I doubt the ingenuity of man, which is apparently limitless with regard to the possibility of making oneself unhappy, but because I believe in the inexhaustible springs of art in the human soul, and also because it is not at all difficult to see the reasons for the current decline of art.

For we, cultured people, turned away from art not consciously and ire of our own free will: we were forced to turn away from it. By way of illustration I can perhaps point to the use of machines for the production of objects in which elements of artistic form are possible. Why does a reasonable person need a car? No doubt to save him labor. There are some things that a machine can do just as well as a human hand armed with a tool. A person does not need, for example, to grind grain in a hand mill - a small stream of water, a wheel and a few simple devices will do this job perfectly and give him the opportunity to think while smoking a pipe or to carve the handle of his knife. This has hitherto been the pure advantage of using machines, always - remember this - presupposing universal equality of opportunity. Art is not lost, but time is gained for leisure or for more enjoyable work. Perhaps a completely reasonable and independent person would stop at this in his relationship with machines, but it is too difficult to expect such prudence and independence, so let us take one more step after our inventor of machines. He has to weave a simple fabric, but, on the one hand, he finds this activity boring, and on the other hand, he believes that an electric loom will be able to weave the same fabric almost as well as a hand loom: therefore, wanting to get more leisure or time for more pleasant work, he uses an electric loom and accepts a slight deterioration of the fabric. But at the same time he did not receive a net gain in art; he made a deal between art and labor and ended up with an incomplete replacement. I am not saying that he may have been wrong in doing so, but I believe that he has lost as much as he has gained. This is exactly how a reasonable person who appreciates art will act in relation to machine technology while he is free, that is, until he is forced to work for the profit of another person, while he lives in a society that has recognized the need for universal equality. But move the machine that creates a work of art one step further, and man loses his superiority, even if he is independent and appreciates art. To avoid misunderstanding, I must say that I mean the modern machine, which appears as if alive and in relation to which man becomes an appendage, but not the old machine, not that improved instrument which was an appendage to man and worked only as long as the hand guided it. Although, I note, as soon as we talk about higher and more complex forms of art, we must discard even such elementary devices. Yes, as regards the actual machines used for artistic production, when they are used for purposes higher than the production of basic necessities, only incidentally endowed with some beauty, a reasonable person who understands art will use them only if he they are forced to do this. If, for example, he likes an ornament, but he believes that a machine cannot do it adequately, and he himself does not want to spend the time to make it properly, then why should he do it at all? He will not want to reduce his leisure time to do something he does not want, unless another person or group of people forces him to. Consequently, he will either do without the ornament, or sacrifice some of his leisure time in order to create a real ornament. The latter will be an indication that he really wants it and that the ornament will be worth his labor; in this case, in addition, work on the ornament will not be burdensome, but will interest him and give him pleasure, satisfying his energy.

This is what, I believe, a reasonable person would do if he were free from coercion on the part of another person. Not being free, he acts completely differently. He has long passed the stage when machines are used only to do work that disgusts the average man, or work that a machine could do as well as a man. And if any industrial product needs to be produced, every time he instinctively waits for a machine to be invented. He is a slave to machines; new car must be invented, and after it is invented, he must - I won’t say: use her, but be used by her, whether he wants it or not. But why is he a slave to machines? - Because he is a slave of a system for the existence of which the invention of machines turned out to be necessary.

Now I must discard, or perhaps have already discarded, the assumption of equality of conditions and remind that, although in some sense we are all slaves of machines, yet some people are directly, and not at all metaphorically, such, and they are precisely those the people on whom most of the arts depend, that is, the workers. For a system that keeps them in a lower class position, it is necessary that they either be machines themselves or servants of machines and in no case show any interest in the products they turn out. While they are workers for their employers, they form part of the machinery of a workshop or factory; in their own eyes they are proletarians, that is, human beings who work to live and live to work: the role of artisans, creators of things of their own free will, has long been played by them.

At the risk of being reproached with sentimentality, I intend to say that since this is so, since the labor of making things that should be artistic has become only a burden and slavery, then I rejoice that at least he is not able to create art and that his products lie somewhere in the middle between numb utilitarianism and the most incompetent fake.

But is it really just sentimental? We, having learned to see the connection between industrial slavery and the decline of the arts, have also learned to hope for the future of these arts, for the day will surely come when men will throw off the yoke and refuse to submit to the artificial coercion of the speculative market, which forces them to waste their lives in endless and hopeless toil. And when this day finally comes and people become free, their sense of beauty and their imagination will be revived, and they will create such art, which they need. Who can say that it will not surpass the art of past centuries as much as the latter surpasses those imperfect relics which remain from the present commercial age?

A few words about an objection that is often raised when I speak on this topic. They can say and usually say: “You feel sorry for the art of the Middle Ages (this is really true!), but the people who created it were not free; they were serfs, they were guild artisans, caught in the steel vice of trade restrictions; they had no political rights and were subjected to the most merciless exploitation by their noble class masters.” Well, I fully admit that the oppression and violence of the Middle Ages influenced the art of that time. His shortcomings are undoubtedly caused by these phenomena; they suppressed art to a certain extent. But that is why I say that when we throw off the present oppression, as we threw off the old, we can expect that the art of the era of true freedom will surpass the art of the former cruel times. However, I maintain that organic, socially promising advanced art was possible in those days, while the pitiful examples of it that remain now are the fruits of hopeless individual efforts, and they are pessimistic and backward-looking.

And that optimistic art can exist in the midst of all the oppression of past days because the instruments of oppression were then completely obvious and acted as something external to the work of the artisan. These were laws and customs openly designed to rob him, and it was obvious violence, like highway robbery. In short, industrial production was not then a weapon for the robbery of the “lower classes”; now it is the main instrument of this deeply revered activity. The medieval craftsman was free in his work, so he made it as fun as possible for himself, and therefore everything beautiful that came out of his hands spoke of pleasure, not pain. A stream of hopes and thoughts poured out onto everything that man created, from a cathedral to a simple pot. So, let's try to express our thought in such a way that it would be the least respectful towards the medieval artisan and the most polite towards today's “worker”. Poor fellow of the 14th century - his work was so little valued that he was allowed to spend hours on it, pleasing himself - and others. But for the overworked worker of today, every minute is very precious and is always burdened with the need to extract profit, and he is not allowed to spend even one of these minutes on art. The current system does not allow him - cannot allow him - to create works of art.

But a strange phenomenon has arisen in our time. There is a whole society of ladies and gentlemen who are indeed very refined, although probably not so enlightened as is usually thought, and many of this refined group really love beauty and life, in other words, art, and are ready to make sacrifices to get it . They are headed by artists with great skill and high intelligence, and in general they are a considerable organism in need of works of art. But these works still do not exist. But the multitude of these demanding enthusiasts are not poor and helpless people, not ignorant fishermen, not half-mad monks, not frivolous ragamuffins - in short, none of those who, by declaring their needs, have so often shaken the world before and will again shake him. No, they are representatives of the ruling classes, rulers of people: they can live without working, and have abundant leisure to think about how to realize their desires. And yet they, I maintain, cannot obtain the art for which they seem to crave so much, although they so zealously scour the world in search of it, sentimentally distressed by the sight of the miserable life of the unfortunate peasants of Italy and the starving proletarians of its cities, - after all, the pitiful poor people of our own villages and our own slums have already lost all picturesqueness. Yes, and everywhere there is not much left for them from real life, and this little is quickly disappearing, yielding to the needs of the entrepreneur and his numerous ragged workers, as well as to the enthusiasm of archaeologists, restorers of the dead past. Soon there will be nothing left but the deceptive dreams of history, except the pitiful remains in our museums and art galleries, except the carefully preserved interiors of our elegant drawing rooms, stupid and counterfeit, worthy evidence of the depraved life that goes on there, a life suppressed, meager and cowardly, rather hiding , than suppressing natural inclinations, which does not, however, interfere with the greedy pursuit of pleasure, if only it can be decently hidden.

The art has disappeared and can no more be “restored” to its former features than a medieval building. Rich and refined people cannot obtain it even if they wished and even if we believed that some of them could achieve it. But why? Because those who could give such art to the rich, they do not allow it to be created. In other words, slavery lies between us and art.

The purpose of art, as I have already found out, is to lift the curse of work, to make our desire for activity express itself in work that gives us pleasure and awakens the consciousness that we are creating something worthy of our energy. And so I say: since we cannot create art by chasing only its external forms, and cannot get anything but crafts, then we just have to try what happens if we leave these crafts to ourselves and try, if we can, preserve the soul of true art. As for me, I believe that if we try to realize the goals of art without thinking too much about its form, we will finally achieve what we want. Whether it is called art or not, at least it will be life, and in the end that is what we crave. And life can lead us to a new majestic and beautiful fine art - to architecture with its versatile splendor, free from the incompleteness and omissions of the art of previous times, to painting that combines the beauty achieved by medieval art with the realism to which modern art strives, as well as to sculpture, which will have the grace of the Greeks and the expressiveness of the Renaissance, combined with some still unknown dignity. Such a sculpture will create figures of men and women, incomparable in life truthfulness and not losing expressiveness, despite their transformation into an architectural ornament, which should be characteristic of genuine sculpture. All this can come true, otherwise we will wander into the desert and art will die in our midst, or it will weakly and uncertainly make its way in a world that has consigned the former glory of the arts to complete oblivion.

In the present state of art, I cannot bring myself to believe that much depends on which of these lots awaits it. Each of them may contain hope for the future, for in the field of art, as in other fields, hope can only rely on revolution. The old art is no longer fruitful and produces nothing but refined poetic regrets. Barren, it must only die, and from now on the matter is how it will die - with or without hope.

Who, for example, destroyed Rouen or the Oxford of my refined poetic regrets? Did they die for the benefit of the people, retreating before spiritual renewal and new happiness, or perhaps they were struck by the lightning of the tragedy that usually accompanies a great revival? - Not at all. Their beauty was not swept away by infantry formations or dynamite; their destroyers were neither philanthropists nor socialists, nor cooperators and nor anarchists. They were sold cheaply, they were wasted due to the carelessness and ignorance of fools who do not know what life and joy mean, who will never take them for themselves and will not give them to people. That is why the death of this beauty hurts us so much. Not a single sane, normally feeling person would dare to regret such losses if they were the payment for a new life and happiness of the people. But the people are still in the same position as before, still standing face to face with the monster that destroyed this beauty and whose name is commercial gain.

I repeat that everything genuine in art will perish at the same hands if this situation continues long enough, although pseudo-art may take its place and develop admirably thanks to amateurish and refined ladies and gentlemen and without any help from the lower classes. And, speaking frankly, I fear that this incoherently muttering ghost of art will satisfy the great many who now consider themselves lovers of art, although it is not difficult to foresee that this ghost will also degenerate and finally turn into a simple joke if everything remains the same. that is to say, if art is to remain forever the entertainment of so-called ladies and gentlemen.

But I personally don’t believe that all this will last long and go far. And yet it would be hypocrisy of me to say that I believe that changes in the foundation of society, which will liberate labor and create true equality among men, will lead us on a short path to the magnificent revival of art of which I have mentioned, although I am quite sure , that these changes will also affect art, since the goals of the coming revolution include the goals of art: to destroy the curse of labor.

I believe that what will happen is something like this: machine production will develop, saving human labor, until the moment when the masses of people have acquired real leisure, sufficient to appreciate the joy of life, and when they have actually achieved such a mastery over nature that will be more afraid of hunger as a punishment for not working hard enough. When they achieve this, they will undoubtedly change themselves and begin to understand what they really want to do. They will soon be convinced that the less they work (I mean work not related to art), the more desirable the land will seem to them. And they will work less and less, until that desire for activity with which I began my conversation prompts them to set to work with fresh strength. But by that time nature, feeling relieved because human labor has become easier, will again regain its former beauty and begin to teach people with memories of ancient art. And then, when the deficiency of the arts, which was caused by the fact that people worked for the profit of the owner, and which is now considered something natural, will be a thing of the past, people will feel free to do what they want and will give up their machines in all cases where manual labor will seem pleasant and desirable to them. Then, in all the crafts that once created beauty, they will begin to look for the most direct connection between man’s hands and his thought. And there will also be many occupations - particularly farming - in which the voluntary use of energy will be considered so delightful that people will not even think of throwing this pleasure into the jaws of a machine.

In short, people will understand that our generation was wrong when it first increased the number of its needs, and then tried - and this was done by everyone - to shirk all participation in the work by which these needs were satisfied. People will see that the modern division of labor is in reality only a new and deliberate form of insolent and inert ignorance, a form much more dangerous to happiness and satisfaction in life than the ignorance of natural phenomena, which we sometimes call science and in which the people of past years thoughtlessly remained. .

In the future it will be discovered, or rather re-learned, that the real secret of happiness is to feel an immediate interest in all the little things of everyday life, to elevate them with the help of art, and not to neglect them, entrusting the work on them to indifferent day laborers. If it is impossible to elevate these little things in life and make them interesting or to facilitate the work on them with the help of a machine so that it becomes completely trifling, this will be an indication that the benefit expected from these little things is not worth the trouble with them and is better from refuse them. All this, in my opinion, will be the result of people throwing off the yoke of the inferiority of the arts, if, of course, and I cannot help but assume this, the impulses are still alive in them, which, starting from the first steps of history, encouraged people to engage in art.

This is how and only this way can the revival of art happen, and I think that this is how it will happen. You might say it's a long process, and it really is. I think it may turn out to be even longer. I presented a socialist or optimistic view of the world. Now comes the turn to present a pessimistic view.

Suppose the revolt against the lack of art, against capitalism, which is now unfolding, will be suppressed. As a result, the workers - the slaves of society - will sink lower and lower. They will not fight against the force that overcomes them, but, prompted by the love of life instilled in us by nature, which always cares about the prolongation of the human race, they will learn to endure everything - hunger, and exhausting work, and dirt, and ignorance, and cruelty. They will endure all this, as they, alas, endure too patiently even now - they will endure so as not to risk a sweet life and a bitter piece of bread, and the last sparks of hope and courage will fade away in them.

Their owners will not be in a better position either: everywhere, except perhaps in the uninhabited desert, the earth will become disgusting, art will completely perish. And like folk arts, literature too will become, as is already happening in our days, a mere collection of well-intentioned, calculated nonsense and dispassionate inventions. Science will become more and more one-sided, imperfect, verbose and useless, until eventually it will become such a heap of prejudices that next to it the theological systems of earlier times will seem to be the embodiment of reason and enlightenment. Everything will fall lower and lower until the heroic aspirations of the past to fulfill hopes will not from year to year, from century to century, become more and more oblivious and man will turn into a creature devoid of hopes, desires, life, a creature that is difficult to imagine.

And will there be at least some way out of this situation? - Maybe. After some terrible catastrophe, man will probably learn to strive for a healthy animal life and begin to change from a tolerable animal to a savage, from a savage to a barbarian, and so on. Millennia will pass before he again takes up those arts that we have now lost, and, like the New Zealanders or the primitive people of the Ice Age, begins to carve bones and depict animals on their polished shoulder blades.

But in any case - according to a pessimistic view that does not recognize the possibility of victory in the struggle against the lack of arts - we will have to wander around this circle again until some catastrophe, some unforeseen consequence of the restructuring of life ends us forever.

I do not share this pessimism, but, on the other hand, I do not believe that it depends entirely on our will whether we will contribute to the progress or degeneration of humanity. But still, since there are still people inclined to a socialist or optimistic worldview, I must conclude by saying that there is a certain hope for the triumph of this worldview and that the intense efforts of many individuals indicate the presence of a force pushing them forward. Thus, I believe that these “Goals of Art” will be achieved, although I know that this will happen only if the tyranny of the inferiority of the arts is defeated. Once again I warn you - you who, perhaps, especially love art - from thinking that you can do anything good when, trying to revive art, you deal only with its external and dead side. I argue that we should strive rather to realize the goals of art than to art itself, and only by remaining faithful to this desire can we feel the emptiness and bareness of the present world, for, truly loving art, we at least will not allow ourselves to be tolerant treat it as a fake.

In any case, the worst thing that can happen to us - and I urge you to agree with this - is submission to evil, which is obvious to us; no illness and no turmoil will bring greater troubles than this submission. The inevitable destruction that perestroika brings should be taken calmly, and everywhere - in the state, in the church, at home - we must resolutely oppose any kind of tyranny, not accept any lies, not be cowardly in the face of what frightens us, although lies and cowardice may appear before us in the guise of piety, duty or love, common sense or pliability, wisdom or kindness. The rudeness of the world, its lies and injustice give rise to its natural consequences, and we and our lives are part of these consequences. But since we are also examining the results of centuries of resistance to these curses, let us all take care together to receive a fair share of this inheritance, which, if it does not give anything else, will at least awaken in us courage and hope, that is, living life, and this, more than anything else, is the true goal of art.

Russell Bertrand

50. Goals of Philosophy From the very beginning, philosophy had two different goals, which were considered to be closely related. On the one hand, philosophy strived for a theoretical understanding of the structure of the world; on the other hand, she tried to find and tell the best possible image

From the book 7 Strategies for Achieving Wealth and Happiness (MLM Gold Fund) by Ron Jim120. Ends The main things (ends) that seem important to me in themselves, and not just as a means to other things, are knowledge, art, unaccountable [???] happiness and relationships of friendship and

From the book The Gutenberg Galaxy author McLuhan Herbert Marshall From the book Favorites: Sociology of Music author Adorno Theodor W From the book The Soviet System: Towards an Open Society author Soros GeorgeMedieval illumination, gloss and sculpture are aspects of the most important art of manuscript culture - the art of memory. This lengthy discussion of the oral aspects of manuscript culture - in its ancient or medieval phase - allows us to overcome habit

From the book Comments on Life. Book one author Jiddu KrishnamurtiSelf-knowledge of art as a problem and as a crisis of art Contemporary art in the West has long been in such a state that the prospects for its further development seem very unclear and uncertain. A rather superficial glance, not deepened into

From the book THE VERY BEGINNING (The Origin of the Universe and the Existence of God) author Craig William Lane From the book Instinct and Social Behavior author Fet Abram IlyichAction without purpose He belonged to different and widely varying organizations and was actively involved in all of them. He wrote and spoke, collected money, organized. He was aggressive, persistent and productive. He was a very useful person, very much in demand and always

From the book The Politics of Poetics author Groys Boris EfimovichLiving without a goal? Most people who deny the presence of a goal in life still live happily - either by inventing some kind of goal for themselves (which, as we see in the example of Sartre, comes down to self-deception), or without making final logical conclusions from their views. Let's take, for example ,

From the book The Truth of Being and Knowledge author Khaziev Valery Semenovich3. Goals of culture The highest goal of culture is man. Culture creates man - its highest goal - by setting before him ideal goals, distant and immediate. The distant goals of culture have a decisive influence on the immediate ones. They express human instinctual attitudes,

From the book Dialectics of the Aesthetic Process. Genesis of sensual culture author Kanarsky Anatoly StanislavovichFrom the work of art to the documentation of art Over the past few decades, the interest of the art community has increasingly shifted from the work of art to the documentation of art. Such a shift is a symptom indicating a more general and deeper

From the author's book11. Goal structure The development of the “goal” category is an important and relevant task of social cognition. “Forecasting”, “foresight”, “planning” - all these concepts of social science are in one form or another connected with the concept of “goal”. A goal is a consistent

From the author's book From the author's bookMythology. About the beginning of the development of art and its main contradiction. The Origins of Decorative and Applied Art Apparently, humanity had a hard time parting with that way of exploring the world, in which man himself was considered the highest - albeit unconscious - goal, and