Educational novel in world literature. Parenting novel

MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY

THEM. M. V. LOMONOSOV

FACULTY OF PHILOLOGY

Department of History of Foreign Literature

Graduate work

5th year students of the department of Romance-Germanic philology

Campion of Natalia Vladimirovna

19th-century English education novel

(C. Dickens, D. Meredith)

Scientific director

Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor

Moscow, 2005

Introduction.

The problem of education is dominant in all the vast novel literature. The topic of perception of the world and the formation of a person under the influence of the reality around him worried many minds. How should a modern person live and think in order to become worthy of the “highest of titles: man”? What forces, drawn from nature, from spiritual culture, from the concrete, historically conditioned social existence of mankind, can and should contribute to this goal?

It is no coincidence that the novel of education as a separate genre arose in the Age of Enlightenment, when the problems of enlightenment, education and upbringing were especially acute, when travel became an integral part of the formation of an educated, humane and sympathetic personality to the suffering of others.

In each country, these problems were conditional or purely personal in nature, but they were always designed for the gradual improvement of the individual, the use of moral categories and standards developed by social institutions and, above all, religion.

The social consciousness of the era appealed to an individual capable of learning the lessons of the past, the lessons of history, adapting to the environment, to an individual who had learned certain conditions of existence in a team, without losing his integral individual appearance. In the novel of education, the already given and accepted rules of behavior should be implemented, but at the same time it was assumed that the high road in life will finally shape the character, so very often teachings and wanderings act as the main components of the genre structure.

This problem is addressed in the classic educational novel “The Study Years of Wilhelm Meister” (1796) by Goethe. We first find Wilhelm as a child interested in puppet theater. The son of a wealthy burgher family, since childhood he has been drawn to everything spectacular and exceptional. In his youth, when love comes to Wilhelm, and with it an uncontrollable passion for the theater, he is distinguished by the same dreaminess (“...Wilhelm soared blissfully in the highest spheres”), optimism, enthusiasm, reaching the point of exaltation, which are characteristic of all the main characters of educational novels during a certain period of their formation. And then lesson after lesson, received by the hero from the reality around him as bringing him closer to life, knowledge of it.

Wilhelm's internal growth is associated with his gradual penetration into the destinies of the people around him. Therefore, almost every character in Goethe’s novel symbolizes a new milestone in the development of the hero and is a kind of lesson for him. This is how the truth of life is introduced into the novel of education.

We must live with open eyes, learning everything and from everyone - even from a small child with his unconscious “why,” says Goethe. Communicating with his son Felix, Wilhelm is clearly aware of how little he knows of the “open secrets” of nature: “Man knows himself only insofar as he knows the world, which he is aware of only in contact with himself, and himself only in contact with the world.” , with reality; and every new object we see gives rise to a new way for us to perceive it.

“It is good for a person who is just entering life to have a high opinion of himself, to count on acquiring all sorts of benefits and to believe that there are no obstacles to his aspirations; but, having reached a certain degree of spiritual development, he will gain a lot if he learns to dissolve in the crowd, if he learns to live for others and forget himself, working on what he recognizes as his duty. Only here is it given to him to know himself, for only in action can we truly compare ourselves with others.” In these words of Jarno addressed to Wilhelm, the theme of the continuation novel is already outlined - “The Years of Wanderings of Wilhelm Meister”, where instead of an isolated dreamer striving for the aesthetic enrichment of his spirit, for harmony within his inner world, a person acts, people act, putting their goal is “to be useful to everyone,” dreaming of a reasonable combination of the personal and the collective.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau addresses the same topic in his novel “Emile, or On Education” (1762). Rousseau's educational system is based on the principle: “Everything is beautiful when it comes out of the hands of the Creator, everything deteriorates in the hands of man.” From this premise, Rousseau deduces both the tasks of ideal education and the goals of the educator. To enhance the beneficial influence of nature, it is necessary to isolate the student from the surrounding society. In order to preserve intact the natural feelings of a naturally virtuous pet, Rousseau proposes a rational course of physical education, as well as intellectual education (teaching the sciences is possible only through a visual system, in acquaintance with nature; it is not for nothing that Rousseau almost completely excludes reading from the field of education, making an exception for two books - Plutarch's Lives and Defoe's Robinson Crusoe). Rousseau insists on the need to master a useful craft for life. But the main thing is the education of the child’s soul and, above all, sensitivity, which includes the ability to sympathize with others, to be kind-hearted, and humane. Cultivating sensitivity is possible only if those around him are attentive and sensitive to the child and respect his personality.

To the four books about the upbringing of a young man, Rousseau adds a fifth book - about the upbringing of a girl. The writer is an opponent of the same education and training of boys and girls. Since the goal of raising a girl is to prepare her for the role of an exemplary wife and mother, the content of all educational activities and the range of subjects and crafts studied change.

For the education of a member of society, according to Rousseau, religion is of great importance. Rousseau believes that ideal religion meets the requirements of nature and natural human feelings. Religiosity itself has two sources - the cult of nature and the cult of the human heart. Such a religion is natural, Rousseau asserts, and every person, obeying instinct, must believe in the Supreme Being who created nature and man, endowing him with a heart and conscience. The temple of such a religion is all of nature and man himself. This ideal religion does not need cult forms and dogmas; it is non-church, free and individual and requires only one thing - sincere feelings and good deeds.

The image of an ideal personality in Rousseau's educational system appears as a natural person, and the purpose of education, according to his views, is to raise a natural person and realize an ideal society in which a natural person will become a citizen.

Both works had a huge public resonance not only in their homeland, but also abroad. Goethe's novel became a canon, Rousseau's work caused serious controversy about the specifics of natural man and the opposition between nature and civilization. Thus, Rousseau initiated a discussion not only about education as such, but also about methods and techniques.

In England, the novel of education had a strange fate. In the 18th century, pragmatic Englishmen preferred a concrete set of rules of conduct as a guide and complement to education. The so-called ‘conduct books’ were widely circulated among different segments of the population, but both Goethe and Rousseau could not ignore the enlightened citizen. In English literature, which had already noted an interest in the problems of education and enlightenment, with the publication of Chesterfield’s “Letters to his Son,” serious opposition to Rousseauism emerged. But there were also his like-minded people and supporters. In addition, in England in the 18th century, in connection with the spread of Cervantes’ Don Quixote archetype, parodies and satirical attacks against book education, isolated and divorced from practical activity, appeared. The national mentality determined the development of a specific genre of the novel about the education of an individual oriented to life in a democratic society. Various educational systems have emerged for young people of both sexes.

The 19th century was undoubtedly associated with the 18th problems of upbringing and education. But it was also the age of the novel. And, naturally, as a genre variety, the novel of education not only showed itself to be independent; the concepts of enlightenment, education and upbringing fit organically into the huge mass of Victorian literature.

The 19th century in England is associated with the long reign of Queen Victoria (), but its significance for the subsequent development of English history, culture, and literature cannot be overestimated. It was during this period that England acquired the status of a great colonial power and formed a national idea and identity. Victorianism left in the minds of the British a certain understanding of the inviolability of traditions, the importance of democracy and moral philosophy, as well as a desire to turn to time-tested emblems and symbols of the Victorian faith. It was the Victorians, with their great literature, who proved the enduring importance of spiritual values in the formation of the national mentality and determining the place of the individual in the history of civilization. The works of Charles Dickens and the Bronte sisters, E. Gaskell, J. Eliot, E. Trollope reflected the features of the social and political development of England with all the difficulties and contradictions, discoveries and miscalculations.

The successes of a prosperous industrial power were demonstrated at the World's Fair in London in 1851. At the same time, stability was relative; more precisely, it was supported and strengthened by the family, home, and the development of a certain doctrine of behavior and morality. Frequent changes of governments (Melbourne, Palmerston, Gladstone, Disraeli, Salisbury) also indicated a change in priorities in foreign and domestic policy. The democratization of society was determined both by the constant fear of a possible threat from revolutionary-minded neighbors (France, Germany, and America), and by the need to bridge the gap between the upper and middle strata of English society. The latter became a reliable stronghold of the nation and consistently achieved success in gaining power. The upper strata of society, which lost their influence after the industrial revolution, nevertheless retained their influence among the middle classes in matters of morality, style, and taste.

The symbol of Victorianism becomes a large family, a cozy home, and rules of behavior in good society. What to wear, how and when to contact whom, the ritual of morning visits, business cards - these unwritten rules contained many dangers for the uninitiated. The Victorians paid special attention to the country house, which reflected their well-being, idea of peace and family happiness. Despite its large size, a Victorian home should be a cozy home and conducive to a happy family life. This life often contained a strong religious aspect. It was considered necessary to go to church, read religious books, and help the poor. Keeping a diary recording detailed affairs occupied a certain portion of the time of the upper class. By 1840, tea at five o'clock had become a sign of a fashionable home. Lunch moved to seven or eight o'clock, and conversations with friends before and after it became necessary and integral parts of country life. In the second half of the century, many country houses had central heating and gas or oil lamps in main rooms and hallways, although candles and coal-burning fireplaces were ubiquitous (electricity came to Victorian homes after 1889). Victorian houses had a large staff of servants who occupied an entire outbuilding or wing. Sometimes the number of servants working in the house, garden and stables was 50 people. Strict organization of the household, subordination and clear distribution of responsibilities made the country house cozy for a family with numerous children, nannies, governesses, and maids.

All these details of everyday life are extremely important for the formation of Victorian ideology and national identity, reflected not only in the literature and culture of this period, but also for the further development of archetypal images and pictures of life, usually associated with the appearance of the Victorian era.

In the Victorian era, education and upbringing became part of government policy. Religious upbringing shapes the moral character of a child, and education is inconceivable without upbringing. School education became the subject of the most bitter debates, and Victorian writers turned to the image of private schools and teachers to express their views on all the abuses and errors that were made in education.

Comfort and convenience created favorable conditions for the individual to realize confidence in the future and pride in the country, which formulated a system of life values and standards of behavior and education in the famous works of Carlyle. Work hard and don’t get discouraged, be patient, demanding of yourself, well-educated and aware of your place in society - this is a set of concepts that formed the basis for the formation of personality.

A distinctive feature of Victorian literature is its position between romanticism and realism, as well as the dominant role of the novel.

The current state of the novel in the Victorian era was determined by its dominant position in society, as the most adequate and complete reflection of the panorama of life; at the same time, the very concept of the genre changed due to the fact that art moved further and further from imitation, imitation, the status of the novel in the Victorian era was exceptionally favorable, the queen herself was interested in the works of her contemporaries. The novel contributed to the formation of public opinion in connection with the spread of education and enlightenment among the population. The wording and terms were refined as the novel acquired the status of the main generator of ideas for maintaining stability and order in society. Being a public nation, England made the novel part of the socio-political life and existence of a citizen concerned not only with his rights, but also with his responsibilities. Victorian prose was focused on educating the citizen.

This work aims to study the national version of the novel of education. I have chosen novels in which the story of a young man is combined with the ideological and moral principles of Victorian society, namely: “The Life of David Copperfield, Told by Himself”

Charles Dickens, “The History of Pendennis, His Fortunes and Misadventures, His Friends and His Worst Enemy” and “The Trial of Richard Feverel” by D. Meredith.

ChapterI: The origins of the national version of the novel of education.

1.1. Education in England in the 19th century.

The first half of the century was better known for debate than for decision-making. The 1850s were to some extent a turning point in the sense that the initiatives taken during these years had a certain influence on the further course of events. The most important reform was the creation in 1856 of the Department of Education. It should be noted that by this time primary education did not meet the requirements at all. A significant contribution to improving the current situation was made by Sir James Kay Shuttleworth, “the man to whom, probably more than any other, we owe national education in England.” By the middle of the century, more and more funds were allocated for the development of education, however, the impression was created that not all funds were spent for their intended purpose. And in 1858, the Newcastle Commission was created, which was tasked with “to inquire into the Present State of Popular Education in England, and to consider and report what measures, if any, are required for the Extension of sound and cheap Elementary Instruction to all Classes of People". The commission that reported on the state of education in 1861 was pleased with the results of the inspection, although out of 2½ million children only 1½ million attended school. Debates over the state of education continued throughout the 1860s and ended in 1870 with the Education Bill of W. E. Forester. This bill expanded the influence of the state, and by 1891 anyone could receive an education. However, school attendance from age 12 onwards became compulsory only in 1899.

Despite the efforts of Thomas Arnold in carrying out the reform of secondary education, living conditions, the attitude of teachers and high school students towards boys, and the general morale in most public and private schools left much to be desired. Constant conflicts led to the creation in 18. the Clarendon Commission to examine the condition of public schools, and also (in 18) the Taunton Commission, whose task was to compile a report on the condition of private schools. The Public Schools Act of 1868, the Endowed Schools Act of 1869, and the work carried out by various subsequent commissions gradually led to significant improvements. This also applies to secondary education for girls, which did not exist until Miss Buss and Miss Beale led the movement in 1865, which resulted in the possibility of education for the female half of the population.

Higher education also underwent changes in the 1850s. In 1852, a commission was created to investigate the state of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Passage of the Oxford University Act 1854 (The Oxford University Act of 1854), as well as the Cambridge University Act 1856. (The Cambridge University Act of 1856) led to significant changes in administration and led to an increase in the list of subjects studied. The Oxford and Cambridge Act of 1877 led to further changes in governance. In addition to Oxford and Cambridge, there was the University of London, several branches of which were opened in the 1850s, Owens College, Manchester, which later became the University of Manchester, opened in 1851. and became one of the provincial universities founded in the 19th century.

The 1851 World's Fair in London brought attention to the need for scientific/technical education, leading to the creation of the Science and Art Department. With the development of industry, the popularity of technical institutes increased; by 1851 there were 610 of them.

“Never perhaps, in the history of the world there existed a period in which more has been said and written on the subject of education than during the last half century,” the author wrote in an article on women’s education. The middle of the century was marked by increased interest among the general public in educational issues. This is what the Educational Times, founded in 1847, writes in one of its editorials: “At a time when education is at length beginning to receive something like its due share of public attention, and when efforts are being made in all directions to “elevate it to its proper position and to diffuse it more widely among our fellow countrymen, a periodical devoted to this important subject appears to be imperatively required.” In the early 1850s, interest in educational issues increased so much that it became a “mania.” A schoolteacher writing in All the Year Round in 1867 speaks of the "educational craze fifteen years ago<…>when hordes of visitors arrived in the schools to watch the teachers in action". Another indicator of public interest was the huge number of letters received by the editors of periodicals containing questions relating to education (the number of letters received by the Guardian, for example, increased significantly between 1849 and 1853.

Public interest in educational issues was undoubtedly reflected in periodicals of various kinds. This topic received special attention in weekly publications, but monthly and quarterly publications also did not ignore it: the Westminster Review showed particular interest in this issue - it began publishing reviews of books on education. Weekly publications such as the Atheneum, the Leader, the Saturday Review, the Spectator, and the religious Guardian published a huge number of articles. The issue of the public education system was raised most frequently, but it was not the only topic of discussion; information about vocational education, as well as education systems in other countries, was provided to the public.

Based on the frequency of publication, these publications can be divided into the following categories:

1) quarterly (Quarterly Reviews), in turn divided into literary and general - Edinburgh Review (1846-60), North British Review (1846-60),

Quarterly Review (1846-60), Westminster Review (1846-60) and religious - British Quarterly Review (1846-60), London Quarterly Review (1853-60);

2) monthly (Monthly Magazines) - Bentley's Miscellany (1846-60), Blackwood's Magazine (1846-60), Dublin University Magazine (1846-60), Fraser's Magazine (1846-60), Macmillan's Magazine (1846-60) , Cornhill Magazine (1860);

3) weekly (Weekly Reviews and Newspapers), in turn divided into literary and general - Atheneum (1846-60), Leader (1850-60),

Saturday Review (1855-60), Spectator (1846-60) and religious - Guardian (1846-60), as well as Weekly Journals - Household Words (1850-59), All the Year Round (1860),

Once a Week (1860).

Extensive discussions also developed on the pages of pedagogical publications, in particular magazines, which became a hallmark of the 1850s. The topic of the day, public education, was discussed here along with the question of the status of teachers. At the same time, on the pages of these magazines there were many discussions about the methods and principles of children's education, the attitude of parents, and child psychology. To list just a few of these publications: British Educator (1856), Educational Expositor (1853-55), Educational Gazette (1855), Educational Guardian (1859-60), Educational Papers for the Home and Colonial School Society (1859-60), Educational Record (1848-60), Educational Times (1847-60), Educator (1851-60), English journal of Education (1846-60), Family Tutor (1851-55), Governess (1855), Mother's Friend (1848 -60), Papers for the Schoolmaster (1851-60), Pupil-Teacher (1857-60), School and the Teacher (1854-60), Teacher's Visitor (1846-49).

Victorian writers also shared an interest in the problems of education and upbringing. It should be noted that this topic was of interest to literary minds long before that (“The Man of Feelings” by G. Mackenzie, “The Mentor” by S. Fielding, etc.). Thus, it is not surprising that such interest was reflected in a fairly large number of novels devoted to the problems of upbringing and education, written during the period of the late 18th - early 19th centuries. Among Rousseau's followers we can note the novels by H. Brook “The Fool of Quality” (1766-70), “Standford and Merton” (“Standford and Merton”, 1783) by Thomas Day (Thomas Day) and “Celebs in Search of a Wife” (“ Coelebs in Search of a Wife”, 1809) by Hannah More. The legacy of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister was reflected at the beginning of the 19th century in the novels of Dickens and Bulwer-Lytton. In Dickens, various literary impulses merge with an awareness of the tragic situation of children and knowledge of the social system. The theme of upbringing and education is central to most of his works; Take, for example, David Copperfield (1850), Hard Times (1854), Great Expectations (). Ruth (1853) by Elizabeth Gaskell is another 1850s novel where education plays an important role. The ongoing debate and enormous interest in the problem of education were also reflected in a large amount of literature, the purpose of which was to show a certain aspect, one or another side of the education system. Such works include: C. Bede “The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green. An Oxford Freshmen” (), F. W. Farrar “Eric or Little by Little; A Tale of Roslyn School” (1858) and “Julian Home. A Tale of College Life” (1859), C. Griffith “The Life and Adventures of George Wilson. A Foundation Scholar” (1854), Rev. W. E. Heygate “Godfrey Davenant. A Tale of School Life” (1852), Rev. E. Manro “Basil the Schoolboy. Or the Heir of Arundel” (1856), F. E. Smedley “Frank Farleigh” (1850).

1.2. Features of a novel of education.

What are the typical features of the novel of education (German Bildungsroman) in its classical manifestation, if we start from the question of its distinctive features?

Based on the position that the novel is an “emerging genre” and that “the novel does not allow any of its own varieties to stabilize,” we can explain the fact that the novel of education does not lend itself to a firm definition and the term itself is not particularly specific (there is no unambiguous translation into Russian of the word Bildung; in German it means “education”, “formation”, “upbringing”). Therefore, we can only talk about a whole system of features of an educational novel, a typical combination of which allows one or another work to be classified as this genre variety. Of course, having once emerged, the novel of education did not pretend to be able to combine all the signs of a branch of the genre. It will continue to develop, improving, acquiring more and more new qualities. But the main, most essential properties of the Bildungsroman first attracted attention in the first example of the genre - the novel “The History of Agathon” (1767).

The term “novel of education” first of all means a work in which the dominant plot structure is the process of educating the hero: life for the hero becomes a school, and not an arena for struggle, as it was in an adventure novel. The hero of the novel of education does not think about the consequences that are caused by one or another of his actions, he does not set himself only narrowly practical goals, the achievement of which he would strive to subordinate all his behavior to them. He is looking for himself. Life itself leads him, teaching him lesson after lesson, and he gradually rises to the only ideal - to become a man in the full sense of the word, to be useful to society.

The hero of an educational novel, in contrast to the hero of an adventurous and old family novel, is important in himself, interesting for his inner world, its development, which manifests itself in relationships with other characters and is revealed in collisions with the outside world. Events of external reality are attracted by the author taking into account this internal psychological development. The author of the novel forces the reader to trace how life, starting from a person’s childhood until the completion of the formation of his character, teaches him lesson after lesson: teaches him with its positive and negative manifestations, light and dark sides, teaches him, including him in active work and leaving him in some cases. a passive observer, teaches to understand the theory and practically apply the acquired knowledge. Each lesson is a higher step in the development of the hero.

The central character of the novel of education strives for active work aimed at establishing justice and harmony in human relations. The search for higher knowledge, the meaning of life is an integral feature of it.

The basis of the composition of the hero’s image is his development from childhood until the moment when he appears before the reader as a person with a fully formed worldview and relatively stable character traits, a person who harmoniously combines physical development with spiritual development. Hence, the entire storyline of the novel of education is conducted by the author through the depiction of the hero’s inner life using the method of introspection. The hero himself observes his improvement, the formation of his consciousness. Everything that happens around him, events in which he himself participates or observes them from the outside, his own actions and the actions of other people are assessed by the hero in terms of their impact on his feelings and consciousness. He himself rejects everything, in his opinion, that is unnecessary and consciously consolidates everything positive that life offers him. For the first time in the novel genre, the hero’s internal monologues appear in this regard, in which he talks to himself, sometimes looking at himself as if from the outside.

The composition of the image of the protagonist of the novel of education is also characterized by the method of retrospection. Reflections on a certain period of time, analysis of one’s behavior and conclusions drawn by the hero sometimes turn into entire excursions into the past, into memories that are highlighted by the author in special chapters. Clarity in such a plot is sometimes lacking, because all the author’s attention is directed to the formation of personality and the entire action of the novel is concentrated around this main character and the main stages of his spiritual development.

Other characters are sometimes outlined weakly, schematically, their life destinies are not fully revealed, since they play an episodic role in the novel: at the moment they contribute to the formation of the character of the hero.

Those stages of development through which the hero of an education novel passes are often stereotypical, that is, they are distinguished by the presence of parallels in other examples of the same genre variety. For example, the hero’s childhood years most often pass in an atmosphere of extreme isolation from all the adversities of the surrounding life. The child either accepts from his teachers ideal, embellished concepts of reality, or, left to himself, creates a fantastic world out of incomprehensible phenomena in which he lives until his first serious encounters with reality.

The harmful effect of such upbringing is the mental suffering of the hero - a typical feature of the novel of upbringing. The author builds the plot on the collision of the hero’s lifeless ideals with the everyday life of society. Every collision is an educational moment, for no one is able to educate a person as faithfully as life itself can do (it is precisely this view of education that the people from the fantastic tower in Goethe’s novel adhere to), and life mercilessly shatters all illusions, forcing the hero step by step develop in oneself the qualities that a person needs in society.

The conflicts that arise between the hero and the active life into which he gradually becomes involved are diverse. But the path of the hero of the novel of education, during which the true formation of his personality occurs, basically comes down to one thing: this is the path of a person from extreme individualism to society, to people.

The path of search and disappointment, the path of broken illusions and new hopes gives rise to another difference in the novels of education: their heroes, as a result of their formation, acquire qualities that to some extent make them similar to each other: rich imagination in childhood, enthusiasm reaching the point of exaltation in childhood. youth, honesty, thirst for knowledge, desire for active work aimed at establishing justice, harmony in human relationships and, most importantly, the hero’s inclination for philosophical reflection and reflection. From here, philosophical and ethical motifs often run through the entire novel, which are presented to the reader through the reflections of the hero, or, most often, in the form of debates and dialogues.

Reflections on philosophical, moral, and ethical topics in educational novels are not an accidental phenomenon. In them, more than in any other types of novels, the personal experience of the author is reflected. The novel of education is the fruit of long observations of life, it is a typification of the most painful phenomena of the time.

ChapterII: "David Copperfield" by Charles Dickens.

Charles Dickens is one of those writers whose fame never faded, either during his lifetime or after his death. The only question was what each new generation saw in Dickens. Dickens was the mastermind of his time, signature dishes and fashionable suits were named after his heroes, and the antiquities shop where little Nell lived still attracts the attention of numerous London tourists.

Dickens was called a great poet by his critics for the ease with which he mastered words, phrases, rhythm and image, comparing him in skill only to Shakespeare.

Guardian of the great tradition of the English novel, Dickens was no less a brilliant performer and interpreter of his own works than their creator. He is great both as an artist, and as a person, and as a citizen who stands up for justice, mercy, humanity and compassion for others. He was a great reformer and innovator in the genre of the novel; he managed to embody a huge number of ideas and observations in his creations.

Dickens's works were successful among all levels of English society. And this was no accident. He wrote about what everyone knows well: about family life, about grumpy wives, about gamblers and debtors, about the oppression of children, about cunning and clever widows who lure gullible men into their networks. The power of his influence on the reader was akin to the influence of acting on the public. Dickens's public readings formed part of the artist's creative laboratory; they served him as a means of communicating with his future reader, testing the vitality of his ideas and the images he created.

Dickens's particular interest in childhood and adolescence was inspired by his own early experiences, his understanding and sympathy for disadvantaged childhood, and his understanding that the situation and condition of the child reflected the situation and condition of the family and society as a whole.

The ideal of family, a home, not only to Dickens, but also to many of his contemporaries, seemed to be a bulwark against the invasion of worldly adversity and a refuge for mental relaxation. For Dickens, the hearth is the embodied ideal of comfort, and according to the statement, this is “a purely English ideal.” This is something organic to the worldview and social hopes of the great writer and an image lovingly painted by him. Dickens was by no means mistaken about the actual state of the English family in different social strata, and his own family, which ultimately fell apart, was a cruel lesson for him. But this does not prevent him from preserving for himself the ideal of nepotism, finding support for it in the same reality, and depicting “ideal” families that are close to the ideal.

“One who has learned to read looks at a book quite differently from an illiterate person, even if it is unopened and standing on a shelf.” - For Dickens, this is an observation of fundamental nature and an important premise. Dickens rejoices at the special, updated view of a literate person on the book and counts on this updated view in the fight against social evil and on changing a person for the better. He stands up for broad education, wages a determined fight against ignorance and a system of upbringing, education, and behavior that cripples the young population.

In his early novels, Dickens exposed bourgeois establishments and institutions and their servants as self-interested, cruel, and hypocritical. For the author of Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, the Poor Law, passed soon after the electoral reforms of 1832 in the interests of industrialists, workhouses, and schools for the poor were the object of criticism, reflecting the mood of the dispossessed masses and the radical intelligentsia.

The very question of the meaning of the system and the role of its servants in the state of society, its morals, in the relationship of social strata and groups, in the struggle between good and evil and its prospects, this question itself, more than ever, is highlighted and emphasized by Dickens. “They tell me from all sides that the whole reason is in the system. There is no need, they say, to blame individuals. The whole problem is in the system... I will accuse the servants of this system in a confrontation before the great, eternal court! This is not Dickens speaking, says one of the characters in the novel Bleak House, Mr. Gridley. However, he expresses the opinion of Dickens himself, his indignation at the smug, arrogant, careless servants of the system and the obedient, cowardly, mechanical performers of official functions. He is increasingly concerned about the state of the system itself, not about individual social institutions, but about the bourgeois system as a whole. “...It seems to me that our system is collapsing,” he will say shortly before his death. The deep doubts that arose in Dickens affected the character, direction and objects of his criticism and his mood.

The origins of the novel of education go back to the 18th century. This traditional genre variety of the novel received its complete classical form in the works of the great German educators K.M. Vilanda, I.V. Goethe. Then the tradition of the novel of education was continued among the German romantics of the first quarter of the 19th century, in the works of realist writers of the past and present. Already at the first stage of the existence of the novel of education, ideas of harmonious development of personality and moral freedom arose. Particular attention was paid to personality development. Writers strived for a deep analysis of the reasons influencing the formation and development of a person, the process of educating the main character.

Most novels of the 19th century are related to the Bildungsroman genre - a novel reflecting “problems of education, upbringing and general development of the character” [Makhmudova 2010: 106]. The study of this novel is associated with the name of the German philosopher and cultural historian W. Dilthey. In his works, he identified three types of educational novel, each of which has its own literary term: “Entwicklungsroman,” or developmental novel; "Erziehungsroman" - novel education or pedagogical novel; "Kunstlerroman" is a novel about a representative of art.

In the book “Questions of Literature and Aesthetics” M.M. Bakhtin examines the problems of the novel of education and its types. The key features in his research are such features as the type of relationship between the author and the hero and the features of artistic space and time. He characterizes the novel of education as an artistic structure, the main organizing center of which is the idea of formation, and distinguishes 4 types: the idyllic-cyclical novel of formation (partly age-related and purely age-related), biographical, didactic-pedagogical novel and the realistic type of novel of formation [Bakhtin 1969: 81 ].

In the monograph “Renaissance Realism,” L. Pinsky connects the features of the novel of education with the tradition of plot-situation and plot-fable. And researcher N.Ya. Berkovsky in his monograph “Romanticism in Germany” puts forward the concept of phylogeny and ontogenesis. According to the author, the European novel of the 18th - early 19th centuries was occupied with “a narrative about how everyday life, family, social and personal well-being are built,” while the novel of education told about “how a person is built and how personality arises” [ Berkovsky 1973: 128].

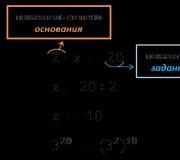

In his work “The Educational Novel in German Literature of the Enlightenment” A.V. Dialektova highlights the theoretical problems of the educational novel and gives this genre variety a definition: “The term educational novel means a work in which the dominant plot structure is the process of educating the hero: life for the hero becomes a school” [Dialektova 1982: 136].

The West German literary critic J. Jacobs studied the problem of the novel of education. His work illuminates the background of the novel of education, its traditions and development. The author gives Hegel's interpretation of the word “Bildungsroman”. According to G.V. F Hegel, this is “the process of development through which the individual is directly attached to the universal.” Y. Jacobs notes that in the novel of education the main character is at odds with various spheres of the world. The defining criterion of this type of novel is overcoming the gap between ideal and reality, loss of illusions, deep disappointment or death of the hero [Pashigorev 2005: 56].

The artistic nature of the German novel of education allows us to compare it with the French “novel of career” and the English novel of education. The French “career novel” in its structure is the hero’s movement up the social ladder. It depicts the process of adaptation of the hero to unfavorable conditions of social life, the process of his moral degradation. Examples include the novels of O. de Balzac, F. Stendhal’s novel “The Red and the Black,” and “Beloved Friend” by G. de Maupassant. Thus, the basis of the French “career novel” is destruction, moral destruction; in the German novel of education, personality is formed from a positive social perspective; The English novel of education focuses attention on moral and psychological issues; it is characterized by a moralizing tendency (C. Dickens).

The American novel of education has specific features. Its plot is based on the process of formation of the main character, gradual personal development and self-determination, the search for the possibility of self-affirmation in society and self-realization. The environment plays an important role, as well as the events happening to the hero that influence the formation of his personality. The novel of education was based on a description of the hero’s childhood and adolescence, the period of his growing up, and was associated with the concept of the “American Dream” (“The Path to Abundance”, “Autobiography” by B. Franklin). In the twentieth century, ideas of education are transformed, the main problem of the work becomes the inability of the hero to influence his destiny (“The Education of Henry Adams” by G. Adams). Some novels drew a parallel between the “American dream” and “American tragedy” (S. Lewis, T. Dreiser).

Thus, we can highlight the following genre features of the Western European educational novel: the author’s educational position, the depiction of the process of educating the hero from childhood to adulthood; the didactic nature of the ending, the conditioning of the results of the hero’s formation throughout his life; the function of minor characters as “educators” in relation to the main character; close interaction of a person with the environment in the process of formation.

History of Russian literature of the 18th century Lebedeva O. B.

Genre models of the travel novel and the novel of emotional education in the works of F. A. Emin

Fyodor Aleksandrovich Emin (1735-1770) is considered the first original Russian novelist of modern times. This figure in Russian literature is completely unusual, and one might even say symbolic: in the sense that the novel genre was founded in literature by a person whose biography in itself is completely romantic and incredible. There are still many ambiguities in this biography. Emin was the grandson of a Pole who was in Austrian military service and married to a Bosnian Muslim; Emin’s mother was a “slave of Christian law,” whom his father married in Constantinople. The first years of the future novelist's life were spent in Turkey and Greece, where his father was a governor, and Emin received his education in Venice. Subsequently, after exile to one of the islands of the Greek archipelago, Emin's father fled to Algeria, where his son joined him - both took part in the Algerian-Tunisian war of 1756. After the death of his father, Emin was captured by Moroccan corsairs; From captivity in Morocco, Emin fled through Portugal to London, where he appeared at the Russian embassy, converted to Orthodoxy and very quickly mastered the Russian language. In 1761, Emin appeared in St. Petersburg and began teaching numerous foreign languages known to him (according to various sources, he knew from 5 to 12), and from 1763 he acted as a novelist, translator and publisher of the satirical magazine “Hell Mail”.

Emin published for only six years - from 1763 to 1769, but during this short period of time he published about 25 books, including 7 novels, at least 4 of which are original; in 1769, he single-handedly published the magazine “Hell Mail”, where he was the only author and, in addition, actively participated with his publications in other magazines of that year. In order to lay the foundations of the novel genre in Russian literature, Emin was simply an ideal figure: his turbulent youth and universal acquaintance with many European and Asian countries gave him the necessary experience that allowed him to step over a certain psychological barrier that exists in the aesthetic consciousness of Russian prose writers - translators because of the extreme dissimilarity of the picture of the world that grew up in the narrative of the European love-adventure novel with the national Russian public and private life. Emin, on the other hand, felt like a fish in water in a European adventure novel - his own life fit well into the genre framework of an adventure novel, and he himself was quite suitable for its hero. He made himself and his life (or the legend about it, which he himself created - this is still unclear) the subject of a narrative in one of his first novels, “Fickle Fortune, or the Adventures of Miramond” (1763), saying in the preface that in the image One of the heroes of the novel, Feridat, he depicted himself and his life.

The very word “adventure” in the title of the novel indicates that its genre model was based on the traditional adventurous scheme of the travel novel. However, Emin complicated it with numerous realities of other narrative models: “The hero’s voyage by sea is interrupted by shipwrecks or attacks by pirates, on land he is attacked by robbers, he finds himself either sold into slavery, then ascended to the throne, or thrown into the wilds of the forest, pondering the meaning of life , reads some wise book about how to treat subjects, ministers, friends ‹…›. On this basis are superimposed elements of a novel about the education of feelings. ‹…› the hero hides from civilization in some desert and there indulges in moral self-improvement. Numerous author's digressions (especially at the beginning of the novel) are designed to educate the Russian reader in terms of economic, historical and ethno-geographical: the author leads the reader (following Miramond and Feridat) to the Maltese, Kabyles, Marabouts, Portuguese, to Egypt - to the Mamelukes, in France and Poland. Some digressions grow into real essays on morals ‹…›. In some places, inserted short stories are deeply wedged into this motley structure, often of a fantastic nature, reminiscent of the fabulous incidents of the Arabian Nights. All this is held together by the ties of a love conflict, but it comes into its own only after the author has devoted more than a hundred pages to her unique backstory. Probably, one can see an early harbinger in it stories of the soul, which will subsequently occupy a crucial place in the characterology of developed sentimentalism, romanticism and realism.”

Thus, we can say that in his first novel Emin created a kind of encyclopedia of forms of novel narrative and genre varieties of the novel. A travel novel that combines a documentary-essay and a fictional adventure, a love novel, an educational novel, a magical-fantasy novel, a psychological novel, an educational novel - “The Adventure of Miramond” presents all these genre trends of novel narration. And if we take into account the fact that “Miramond’s Adventure” takes place in the geographical space of almost the entire world - from real European and Asian countries to a fictional desert, as well as the fact that the name “Miramond” itself contains twice repeated - in Russian and in French the concept of “world” (the whole world, the universe, social life) - then the concept of the novel genre, as it is outlined in the first Russian original novel, acquires a distinct overtone of epic universality, the comprehensiveness of being, recreated through the fate, character and biography of a peculiar “ citizen of the world."

It is easy to notice that in his first novel Emin picks up the already familiar traditions of Russian original and translated fiction of the 18th century. – from authorless stories about “a citizen of Russian Europe” to the journey of the conventional hero Thyrsis around the fictional Island of Love. Just as the Russian sailor grows spiritually and intellectually from an arty and poor nobleman to an interlocutor of European monarchs, just as Thyrsis becomes a hero, citizen and patriot as a result of mastering the culture of love relationships and nurturing feelings in the “academy of love,” Emin’s hero Miramond is also represented in the process spiritual growth: “it is constantly changing; he becomes more mature, wiser, life experience allows him to understand what was previously inaccessible to him.” This is, perhaps, the main trend that emerged in “The Adventure of Miramond”: the tendency for the novel-journey to develop into a novel - a spiritual path, a tendency towards the psychologization of the novel, which found its full embodiment in Emin’s best novel “Letters of Ernest and Doravra” (1766).

The genre form that Emin gave to his last novel (and the time interval between “Miramond” and “Letters of Ernest and Doravra” is only three years) - the epistolary novel - testifies, firstly, to the rapid evolution of the Russian novel, and secondly, about the rapidity with which the just emerging Russian novelism gained contemporary Western European aesthetic experience and rose to the Western European level of development of the novel genre in terms of the evolution of genre forms of artistic prose. The epistolary novel in the 1760s. was a vital aesthetic innovation not only in Russia, but also in European literature. In 1761, the novel by J.-J. was published. Rousseau’s “Julia or the New Heloise,” which marked a new stage in European novelism both with its class conflict, acutely relevant in pre-revolutionary France, and with its epistolary form, which opened up new opportunities for the psychologization of the novel narrative, since it gave the characters all the traditionally author’s ways of revealing their inner world .

Emin, who gravitated toward the psychologization of the novel narrative already in “The Adventures of Miramond,” certainly felt the opportunities that the epistolary form provides for revealing the inner world of the heroes, and, having adopted the epistolary form of Rousseau’s novel, subordinated all other components to the task of depicting the life of the “sensitive heart.” novel narrative. Having retained the general outlines of the love conflict - Doravra's nobility and wealth prevented her marriage with the poor, unofficial Ernest, he nevertheless softened the severity of Rousseau's love conflict, where the main obstacle to the love of Julia and Saint-Preux was the difference in their class status - the aristocrat Julia and the commoner Saint-Preux could not be happy only for this reason, while Ernest and Doravra both belong to the noble class, and the reasons for the unhappiness of their love are of a different, psychological nature.

Emin focused entirely on the patterns and nature of human emotional life, recreating in his novel the story of the long-term, faithful and devoted love of Ernest and Doravra, which survived all existing obstacles - wealth and poverty, Doravra’s forced marriage, the news that Ernest’s wife, whom he considered dead, alive, but at the moment when these obstacles disappeared (Ernest and Doravra were widowed), the inscrutable mystery and unpredictability of the life of the heart makes itself felt: Doravra marries a second time, but not to Ernest. Emin pointedly does not try to explain the reasons for her action, offering the reader a choice of two possible interpretations: the marriage with Ernest could have been prevented by the fact that Doravra blames herself for the death of her husband, who was shocked when he discovered a bunch of Ernest’s letters in his wife’s possession, and soon after that he fell ill and died . The marriage with Ernest could also have been hindered by the fact that Doravra simply stopped loving Ernest: it is impossible to rationally explain why love arises and it is also impossible to know the reasons why it passes.

Emin himself was well aware of the unusual nature of his novel and the obstacles that the strong foundations of classicist morality and the ideology of educational didactics created for his perception. Rational normative aesthetics required unambiguous moral assessments; Enlightenment didactics demanded from fine literature the highest justice: punishment of vice and reward of virtue. But in the Russian democratic novel, focused more on the sphere of the emotional life of the heart than on the sphere of intellectual activity, this clarity of moral criteria began to blur, the categories of virtue and vice ceased to be functional in the ethical assessment of the hero’s actions. The ending of the love story is not at all what one would expect from a reader brought up on the classicist apology for virtue and the overthrow of vice. In the preface to his novel, Emin tried to explain his initial principles that led the novel to this ending:

‹…› It will be possible for some to discredit my taste due to the fact that the last parts do not correspond to the first, for in the first constancy in love was elevated to almost the highest degree, and in the last it suddenly collapsed. I myself will say that such strong, virtuous and reasonable love should not change. Believe me, kind reader, that it would not be difficult for me to raise my romantic constancy even higher and finish my book to the pleasure of everyone, uniting Ernest with Doravra, but fate did not like such an ending, and I am forced to write a book to her taste...

Emin’s main aesthetic attitude, which he tries to express in his preface, is not an orientation towards the proper, the ideal, but an orientation towards the true, life-like. For Emin, the truth is not the abstract rational formula of passion, but the real, everyday implementation of this passion in the fate of an ordinary earthly inhabitant. This attitude also dictated a concern for reliable psychological motivations for the actions and actions of the heroes, which is obvious in the same preface to the novel:

Some ‹…› will have reason to say that in some of my initial letters there is a lot of unnecessary moralizing; but if they consider that the innate pride of every lover prompts the adored person to show his knowledge, then they will see that much less should be blamed on those who, having corresponded with their mistresses, who are very intelligent, “…› philosophize and subtly discuss various roundabout things so that, In this way, having captivated the mind of a previously strict person, it was possible to more conveniently approach her heart.

However, this focus on depicting the truth of a person’s spiritual and emotional life, largely successfully implemented in Emin’s novel, came into conflict with a completely conventional, non-domestic space: the novel, conceived and implemented as an original Russian novel about Russian people, the writer’s contemporaries, is in no way correlated with realities of national life. Here, for example, is how the hero’s rural solitude is described:

Here nature, in its delicate flowers and green leaves, shows its gaiety and liveliness; here the roses, in vain for us admiring them, blush as if ashamed, and the pleasant lilies, which are not like roses, have a pleasant appearance, seeing their natural shyness, as if in their gentle light they show a pleasant smile. The vegetables of our gardens satisfy us better than the most pleasant and skillfully seasoned foods consumed on magnificent tables. Here, a pleasant marshmallow, as if it had its own home, is hugging with different flowers ‹…›. The pleasant singing of songbirds serves us instead of music ‹…›.

If for the Russian democratic reader of the second half of the 18th century, for the most part unfamiliar with the life of European countries, the exotic geography of “Miramonda” is no different from the conventionally European geography of authorless histories or even from the allegorical geography of the fictional island of Love, then from the Russian novel the Russian the reader had the right to demand recognition of the realities of national life that were practically eliminated from the novel “Letters of Ernest and Doravra.” Thus, the next step in the evolutionary development of the novel turned out to be prescribed by this situation: the life-like novel in spiritual and emotional terms, but conventional in everyday life, is being replaced by Emin’s novel by Chulkov’s authentic everyday novel, created with a democratic attitude towards reproducing another truth: the truth of the national social and private life of the grassroots democratic environment. So the Russian democratic novel of 1760-1770. in its evolution, it reflects the pattern of projection of the philosophical picture of the world onto the national aesthetic consciousness: in the person of Emin, the novel masters the ideal-emotional sphere, in the person of Chulkov - the material and everyday sphere.

From the book World Art Culture. XX century Literature author Olesina E“Necessity” of the novel Gaining and Losing Interest in a person’s life, his actions against the backdrop of historical events gives rise to the actualization of the novel genre. Any novel strives to pose the most pressing and at the same time eternal questions of existence. The ideology of the novel states

From the book “The White Guard” Deciphered. Secrets of Bulgakov author Sokolov Boris Vadimovich From the book MMIX - Year of the Ox author Romanov Roman From the book History of Russian Literature of the 19th Century. Part 2. 1840-1860 author Prokofieva Natalya Nikolaevna From the book History of Russian Literature of the 18th Century author Lebedeva O. B.Genre traditions and the genre of the novel The plot and composition serve to identify and reveal Pechorin’s soul. First, the reader learns about the consequences of the events that happened, then about their cause, and each event is subjected to analysis by the hero, in which the most important place is occupied

From the book Messenger, or the Life of Daniil Andeev: a biographical story in twelve parts author Romanov Boris NikolaevichTranslations of Western European prose. “A Trip to the Island of Love” as a genre prototype of the novel “education of feelings” Another important branch of Trediakovsky’s literary activity was translations of Western European prose. His early Russian narrative works

From the book History of the Russian Novel. Volume 1 author Philology Team of authors --“The Life of F.V. Ushakov”: genre traditions of life, confession, educational novel The very word “life” in the title of the work testifies to the goal that Radishchev wanted to achieve with the biography of a friend of his youth. Life - a didactic genre

From the book Fundamentals of Literary Studies. Analysis of a work of art [tutorial] author Esalnek Asiya YanovnaPractical lesson No. 2. Genre varieties of odes in the works of M. V. Lomonosov Literature: 1) Lomonosov M. V. Odes 1739, 1747, 1748. “Conversation with Anacreon” “Poems composed on the road to Peterhof...”. “In the darkness of the night...” “Morning reflection on God’s majesty” “Evening

From the book History of Foreign Literature of the late XIX - early XX centuries author Zhuk Maxim Ivanovich From the book Demons: A Novel-Warning author Saraskina Lyudmila IvanovnaCHAPTER V. MORAL DESCRIPTIVE NOVEL. GENRE OF THE NOVEL IN THE WORK OF ROMANTICS OF THE 30s (G. M. Friedlander) 1The wide popularity of historical themes in the Russian novel at the turn of the 20s and 30s was ultimately associated with the desire to historically comprehend modernity.

From the book Movement of Literature. Volume I author Rodnyanskaya Irina BentsionovnaThe formation of the novel in the works of A.S. Pushkin Unlike the above-mentioned foreign novels by Rousseau, Richardson, Constant and some others, Pushkin’s novel “Eugene Onegin” recreated a surprisingly reliable picture of Russian noble society -

From the book Essays on the History of English Poetry. Poets of the Renaissance. [Volume 1] author Kruzhkov Grigory MikhailovichThe originality of the novel in the works of I.S. Turgeneva I, S. Turgenev owns several novels (“Rudin” - 1856, “Noble Nest” - 1859, “On the Eve” - 1860, “Fathers and Sons” - 1862, “Nov” - 1877), in each of which has its own and in many ways different heroes. The focus of all novels

From the author's booktopic 4. Genre features of Anatole France’s novel “Penguin Island” 1. The ideological concept and problems of the novel.2. Features of the plot and composition: a) parody element; b) a textbook on the history of Penguinia; c) “satire on all humanity.”3. Objects of satirical image:a)

From the author's book From the author's bookThe stratification of the novel As far as I notice, the vagus discussion nerve has gradually moved from the rather far-fetched postmodern agitation to a much more fundamental question about the fate of artistic fiction, in the form in which it has constituted more than three centuries

The ideological movement, called the Enlightenment, spread to European countries in the 18th century. It was imbued with the spirit of struggle against all creations and manifestations of feudalism. Enlightenment people put forward and defended the ideas of social progress, equality, and free development of the individual.

The Enlightenmentists proceeded from the belief that a person is born kind, endowed with a sense of beauty, justice and equal to all other people. An imperfect society, its cruel laws are contrary to human, “natural”

In kind. Consequently, it is necessary for a person to remember his high purpose on earth, to appeal to him to reason - and then he himself will understand what good is and what evil is, he himself will be able to answer for his actions, for his life. It is only important to enlighten people and influence their consciousness.

The Enlightenmentists believed in the omnipotence of reason, but for them this category was filled with a deeper meaning. Reason was only supposed to contribute to the reconstruction of the entire society.

The future was imagined by the Enlightenment as the “kingdom of reason.” That is why they attached great importance to science, establishing

“cult of knowledge”, “cult of the book”. It is characteristic that it was in the 18th century that the famous French “Encyclopedia” was published in 28 volumes. It promoted new views on nature, man, society, and art.

Writers, poets, and playwrights of the 18th century sought to prove that not only science, but also art can contribute to the re-education of people worthy of living in a future harmonious society, which must again be built according to the laws of reason.

The educational movement originated in England (Daniel Defoe “Robinson Crusoe”, Jonathan Swift “Gulliver’s Travels”, the great Scottish poet Robert Burns). Then the ideas of the Enlightenment began to spread throughout Europe. In France, for example, the enlighteners include Voltaire, Rousseau, Beaumarchais, in Germany - Lessing, Goethe, Schiller.

Enlightenment ideals also existed in Russian literature. They were reflected in the works of many authors of the 18th century, but most clearly in Fonvizin and Radishchev.

In the depths of the Enlightenment, new trends emerged that foreshadowed the emergence of sentimentalism. Attention to the feelings and experiences of the common person is increasing, and moral values are being affirmed. So, above we mentioned Rousseau as one of the representatives of the Age of Enlightenment. But he was also the author of the novel “The New Heloise,” which is rightfully considered the pinnacle of European sentimentalism.

The humanistic ideas of the Enlightenment found a unique expression in German literature; a literary movement arose there, known as “Storm and Drang”. Supporters of this movement resolutely rejected the classicist norms that fettered the creative individuality of the writer.

They defended the ideas of national uniqueness of literature, demanded the depiction of strong passions, heroic deeds, bright characters, and at the same time developed new methods of psychological analysis. This, in particular, was the work of Goethe and Schiller.

The literature of the Enlightenment took a step forward both in the theoretical understanding of the goals and objectives of art and in artistic practice. New genres are appearing: educational novels, philosophical stories, family drama. More attention began to be paid to moral values and the affirmation of the self-awareness of the human person. All this became an important stage in the history of literature and art.

Received quite widespread use in the literature of this era. educational classicism. Its largest representatives in poetry and drama, and especially in the tragedy genre, were Voltaire. “Weimar classicism” was of great importance - its theoretical principles were vividly embodied in Schiller’s poems and in Goethe’s “Iorigenia and Tauris”.

Enlightenment realism was also distributed. Its representatives were Diderot, Lessing, Goethe, Defoe, Swift.

The most famous works of the Age of Enlightenment:

In England: -Daniel Defoe's "Robinson Crusoe", -Jonathan Swift's "Gulliver's Travels", -Richardson's "Pamela or Virtue Rewarded", - The Poetry of Robert Burns

In the book of France: – “Persian Letters” by Montesquieu, – “The Virgin of Orleans”, “The Prodigal Son”, “Fanaticism or the Prophet Mohammed” by Voltaire. – “Ramo’s Nephew”, “Jacques the Fatalist” by Diderot. – “New Heloise”, “Confession” by J.-J. Rousseau.

In Germany: - “Cunning and Love”, “The Robbers” by Schiller, - “Faust”, “The Sorrows of Young Werther” by Goethe.

Studying literary theory in high school

Studying the theory of literature helps one to navigate a work of art, a writer’s work, the literary process, to understand the specifics and conventions of art, fosters a serious attitude towards spiritual wealth, develops principles for evaluating literary phenomena and the ability to analyze them, sharpens and develops students’ critical thought, and contributes to the formation of aesthetic tastes. New things in art will be better understood and appreciated by those who know the laws of art and imagine the stages of its development).

By being included in the general process of shaping the worldview of young people, theoretical and literary knowledge becomes a kind of stimulator for the growth of their communist beliefs.

The study of literary theory improves the techniques of mental activity that are important for the general development of schoolchildren and for the mastery of other academic subjects.

There is another extremely important aspect of the issue. The level of perception of other arts by boys and girls largely depends on how the study of literary theory is organized in school. The primitive-naturalistic approach to films, theatrical performances, and works of painting (as the authors of the collection “Artistic Perception” 1 write with alarm) is explained by the unsatisfactory theoretical preparation of some young people in the field of art. Obviously, in a literature course it is necessary to increase attention to those moments that reveal and characterize the common features of literature and other types of art, the general laws of the development of art, without weakening attention to the specifics of literature.

In grades IV-VI, learning specific information about the differences between prose and poetic speech, about the speech of the author and the speech of the characters, about the visual and expressive means of language, about verse, about the structure of a literary work, about a literary hero, about genera and some genres of literature, getting acquainted with the facts of creative history individual works, with the writer’s attitude to the characters and events depicted, encountering artistic fiction in fairy tales, epics, fables, finding out the vital basis of such works as “The Tale of a Real Man” by B. Polevoy, “Childhood” by M. Gorky, “School” "A. Gaidar, students gradually accumulate observations on the essence of the figurative reflection of life, and consolidate something in the simplest definitions. In this regard, the formulation of a theoretical question about the differences between literature and oral folk art, literary fairy tales and folk tales is of particular importance.

A more systematic study of literary theory begins in grade VII.

VII class. Imagery of fiction. Concept

artistic image. Related question 6: The role of creative imagination. (The formulation of the problem of the imagery of literature is determined by the interests of the literary development of students and the special place occupied by the VII grade as a class, “borderline” between the two stages of literary education - propaedeutic and based on the historical-chronological principle. Since students become familiar with the imagery of literature in theoretical terms when studying individual works, they simultaneously master, in connection with the main concept, the concepts of theme, idea, plot, composition of the work.)

VIII class. Typical in literature. The concept of literary type (in its relationship with the concept of artistic image).

Addressing the problem of the typical is based on the formulation of the problem “author - reality” and involves considering from a certain angle the issue of personal character, artistic creativity, and ways of expressing the author’s consciousness. Favorable conditions for attracting the attention of schoolchildren to issues of the personal nature of artistic creativity are created both by the VIII grade program (studying biographies of writers, working on several works by one author), and by the nature of the works being studied (lyrical and lyric-epic works, first-person narrative form), and the direction of students' cognitive interests.

IX class. Class and nationality of literature (and related issues of worldviews of the writer’s individual style). The promotion of the problem of class and nationality of literature is based on the originality of the IX grade course (fierce class struggle in Russian literature of the 60s of the 19th century, the solution of many fundamental social problems by different writers from different ideological and aesthetic positions) and on the level of preparedness of students in literature and history.

X class. The partisanship of literature and related issues of socialist realism. To comprehend the concepts of partisanship in literature and socialist realism, “peak” concepts that are extremely important for the formation of a worldview and the development of a student’s personality, schoolchildren are prepared essentially throughout the course of literature. In the process of mastering these concepts, students deepen and improve their knowledge both on general problems of fiction and on problems related to the study of a work of fiction.

Thus, in each class a complex of theoretical problems (concepts) is studied, organized by a central “general” problem for this class, and this latter is constantly put in connection with other problems (concepts).

- In 17, a new ideological movement, the Enlightenment, became widespread. Writers, critics, philosophers - Diderot, Beaumarchais, Swift, Defoe, Voltaire and others. A characteristic feature of the Enlightenment was a kind of deification of reason as a single criterion...

- Previously, literary education was based on like-mindedness, classism, socialist stereotypes and party ideas. The works of fiction were a complement to the study of historical manuals. Currently, this education system is...

- The purpose of the course work is to develop students’ basic skills in independent research....

- Students must create and write down an imaginary dialogue. Work can be done in pairs. Topics for dialogue are related to the work being studied: What could roses tell each other about...

- According to sociological research, reading fiction has ceased to be a distinctive feature of our contemporaries. More than 50% of the population report in surveys that in recent years they have stopped reading fiction....

- A literature lesson is a creative process, and the work of a teacher is akin to the work of a composer, painter, actor, director. At all stages of the lesson, the teacher himself plays a significant role...

- The “New Drama” began with realism, with which the artistic achievements of Ibsen, Bjornson, Hamsun, Sgrindberg, Hauptmann, and Shaw are associated, but absorbed the ideas of other literary schools and movements of the transitional era, first...

- In English literature, critical realism established itself as a leading movement in the 30s and 40s. Its heyday coincided with the highest rise of the Chartist movement in the 40s. It was at this time that such...

- Novalis (1772-1801) is the pseudonym of a talented poet who belonged to the Jena circle of romantics, Friedrich von Hardenberg. He came from an impoverished aristocratic family and was forced to earn his living as a bureaucrat. Novalis was...

- Eternal images are the so-called images of world literature, which are indicated by the great power of bad generalization and have become a universal spiritual acquisition. These include Prometheus, Moses, Faust, Don Juan, Don Quixote,...

- Folk oral creativity is the creativity of the people. To designate it in science, two terms are most often used: the Russian term “folk oral poetic creativity” and the English term “folklore”, introduced by William Toms in...

- General characteristics of literature of the 17th century: aesthetic systems and their representatives (detailed consideration of the work of one of them). Italy. The movement of new trade routes had a detrimental effect on Italy's domestic economy. In XVII Italy,...

- Along with the old drama genres to the middle. XVI century In Spain, a new, Renaissance system of dramaturgy is being developed, cat. arose from the collision of two principles in the theater - the medieval folk tradition and the scientific-humanistic...

- A sonnet is a special form of poetry that originated in the 13th century in the poetry of Provençal troubadours. From Provence, sonnet poetry moved to Italy, where it reached perfection in the works of Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarch, Giovanni...

- Starting from the fourteenth century, Italian artists and poets turned their attention to the ancient heritage and tried to revive in their art the image of a beautiful, harmoniously developed person. Among the first to take...

- The literature of Ancient Rome represents a new stage in the history of a single ancient literature. Roman literature preserves the system of genres that arose in Greece and its problems, however, Roman writers develop in their own way a number of problems put forward...

- At the festival of the “Great Dionysius”, established by the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus, in addition to lyrical choirs with the obligatory dithyramb in the cult of Dionysus, also tragic choirs performed. Ancient tragedy names Athens as its first poet Euripides and...

- In the 7th century. BC. The heroic epic lost its leading importance in literature, and lyrics began to occupy first place. This was the result of serious changes that took place in the economic, political and social life of Greek...

- There is no people who do not have songs. Slavic folk songs are distinguished by their remarkable merits. Even before the emergence of the state of Kievan Rus, the songs of the Eastern Slavs attracted the attention of foreign historians with their beauty...

- Fairy tales are collectively created and collectively preserved by the people oral epic narratives in prose with such satirical or romantic content that requires the use of techniques of implausible depiction of reality and in...

England in the 18th century became the birthplace of the Enlightenment novel.

The novel is a genre that arose during the transition from the Renaissance to the New Age; this young genre was ignored by classicist poetics because it had no precedent in ancient literature. The novel is aimed at an artistic exploration of modern reality, and English literature turned out to be particularly fertile ground for the qualitative leap in the development of the genre that the educational novel became.

Hero:

In educational literature, there is a significant democratization of the hero, which corresponds to the general direction of educational thought. The hero of a literary work in the 18th century ceases to be a “hero” in the sense of possessing exceptional properties and ceases to occupy the highest levels in the social hierarchy. He remains a “hero” only in another meaning of the word - the central character of the work. The reader can identify with such a hero and put himself in his place; this hero is in no way superior to an ordinary, average person. But at first, this recognizable hero, in order to attract the reader’s interest, had to act in an unfamiliar environment, in circumstances that awakened the reader’s imagination.

Therefore, with this “ordinary” hero in the literature of the 18th century, extraordinary adventures still occur, events that are out of the ordinary, because for the reader of the 18th century they justified the story about an ordinary person, they contained the entertainment of a literary work. The hero's adventures can unfold in different spaces, close or far from his home, in familiar social conditions or in a non-European society, or even outside society in general. But invariably, the literature of the 18th century sharpens and poses, shows in close-up the problems of state and social structure, the place of the individual in society and the influence of society on the individual.

In English literature, the Enlightenment goes through several stages: