Archaeological cultures of the late Paleolithic. Cultural areas and archaeological cultures Narva and Upper Dnieper cultures

During the Final Paleolithic era, settlements of the Grensk culture (Belarusian) Russian appeared in the Middle Dnieper region. From the west, settlement by tribes of the Svider culture began. Settlements of other archaeological cultures are also known, including Arenburg and Tardenoise.

Settlement occurred primarily along river banks; The river watersheds remained largely uninhabited.

Mesolithic

Archaeological sites of the Mesolithic era. Monuments belonging to several cultures are marked in black. Janislavice culture Komornika culture Hrenskaya culture Kunda culture Kudlajevo culture Butovo culture

Around the 10th millennium BC. e. The Ice Age ended and the Mesolithic era began. At this time, the territory of modern Belarus was finally populated. More than 120 Mesolithic settlements are known, among which there are both seasonal sites and small permanent settlements.

The Mesolithic was characterized by an increase in the number of species of flora and fauna. In this regard, in addition to hunting, fishing and gathering also spread. In the Mesolithic, the bow appeared (with bone and stone arrowheads), which significantly increased the efficiency of hunting. The most common type of Mesolithic dwellings in Belarus were light buildings with a diameter of about five meters based on structures made of poles, round or rectangular in plan. Settlements were located on hills near rivers and lakes.

Many Mesolithic monuments are very reminiscent of the monuments of the Svider culture, but they also have a number of features that bring them closer to the autochthonous population that came after the retreat of the glacier a little earlier. There is a lot of evidence that people from other regions migrated to the territory of Belarus: from the south, from the east and from Central Europe.

Archaeological cultures of the Mesolithic

· Grensk culture (beginning in the Final Paleolithic; more than 10 sites are known)

· Komarnica culture

· Janislavice culture (more than 10 sites are known)

· Dnieper-Desninskaya culture (more than 30 sites are known)

· Swider culture

· Kund culture (three sites are known, Verhnedvinsk and Polotsk regions)

· Neman culture (more than 10 sites studied)

· Kudlaevskaya culture

· Untyped settlements with mixed material culture (the area of Lake Naroch and other settlements)

Possibly Tardenoise culture

Neolithic

During the Neolithic period, there was a process of transition from an appropriating to a producing economy, however, on the territory of Belarus, fishing and hunting continued to play the main role, and in the Dvina basin, the widespread occurrence of a producing economy dates back to the late Neolithic.

The beginning of the Neolithic on the territory of Belarus dates back to the appearance of ceramics (the end of the 5th millennium BC in Polesie and the first half of the 4th millennium BC in the central and northern regions). During the Neolithic era, people learned to produce high-quality tools and weapons from flint. At Neolithic sites, bones of wild boar, elk, bison, bear, roe deer, beaver and badger are found. Fishing equipment and remains of primitive boats were also found; it is assumed that the main fishing object was pike. At least 700 Neolithic settlements are known on the territory of modern Belarus, 80% of which belong to the Late Neolithic. Basically, Neolithic settlements (of an open, unfortified type) are located along the banks of rivers and lakes, which is associated with the great importance of fishing in economic life.

Archaeological cultures of the Neolithic

Narva and Upper Dnieper cultures

Narva culture, Pit-comb pottery culture

The Upper Dnieper culture (upper Dnieper region) left up to 500 known sites, of which only about 40 have been explored. At an early stage, the carriers of the culture made thick-walled pots, ornamentation was made with pit impressions and comb imprints. At a later stage, thicker-necked pots with more complex compositions in ornament began to appear.

There were round and oval dwellings, which at a later stage were sunk into the ground. Influence on culture from the outside is observed only at the end of the Neolithic. It is assumed that the Upper Dnieper culture was associated with the Finno-Ugric peoples.

Neman culture

The Neman culture is widespread in the Neman basin (as well as in northeastern Poland and southwestern Lithuania). The culture area extended south to the upper reaches of the Pripyat. The Dubchay, Lysogorsk and Dobrobor periods are distinguished (the basis for the classification is the difference in the methods of making ceramics). It is believed that the culture began to form in the late Mesolithic.

The culture was characterized by above-ground dwellings. The pottery of the Neman culture is sharp-bottomed and insufficiently fired at an early stage. There are traces of vegetation in the clay. The surface of the walls was leveled by combing with a comb.

At the end of the 3rd millennium BC. e. representatives of the Neman culture moved north under the influence of the spherical amphorae culture.

7. Population of Belarus in the Bronze Age.

Bronze Age (2nd millennium BC – beginning of the 1st millennium BC)

The Bronze Age on the territory of Belarus began at the border of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. e. and lasted approximately until the beginning of 1 thousand BC. e. At this time, copper and bronze products from the south enter the territory of Belarus. There were no deposits of copper and tin, the alloy of which forms bronze. People began to domesticate more and more animals, and then moved on to breeding them. The pig was probably the first domestic animal. There is a transition from hunting to animal husbandry and from gathering to agriculture. It meant a transition from an appropriating to a producing economy. With the production type of economy, ancient people with their own labor obtained the products necessary for life, which did not exist in ready-made form in nature. At first, farming was by hoeing, when the main tool of labor was a hoe, and then by slash-and-burn. Ancient people carved out the forest with axes, uprooted and burned stumps, used the ashes as fertilizer, and cultivated the land with a harrow. Sickles were used to harvest the crops, and flour was obtained from grain grinders. Flat-bottomed pottery vessels were made to preserve grain and milk from bred animals.

Animal husbandry and slash-and-burn agriculture became the main occupations of men in the Bronze Age. The role of male labor gradually increased. As a result, patrilineal patriarchy replaced the maternal clan.

During the Bronze Age, Indo-Europeans gradually began to penetrate into the territory of Belarus - numerous tribes of nomadic livestock breeders who originally lived in Asia Minor next to the peoples of the Ancient East. During the settlement in Europe, as a result of the mixing of Indo-Europeans with the local population, tribal associations of Germans, Slavs and Balts arose. The Baltic tribes, who are the ancestors of modern Lithuanians and Latvians, began to gradually develop the territory of Belarus, increasing the population.

8. Founded by Indians, their Baltic galina on Belarusian lands.

Indo-European period is the period that began in the Bronze Age during the settlement of Indo-European tribes. At this time in the world there was demographic explosion (overpopulation), and from the territory of Western Asia the Indo-Europeans began to settle in the vastness of Europe and Asia. A separate group of Indo-Europeans turned north to Central Asia, passed between the Caspian and Aral seas, continued their journey through the Volga steppes, and then to the Dnieper. This migration flow became the source of settlement of Indo-Europeans in Europe, including Belarus. The Indo-Europeans were at a higher stage of socio-economic development, so the local population was assimilated(changed, adapted) by them. As a result of migration and mixing with the local population, the Indo-Europeans lost their unity and identity. Today, Indo-Europeans include peoples who speak Slavic, Germanic, Baltic and other languages.

IN III – II millennium BC on the territory that united the river basins. The Vistula, Neman, Western Dvina, Upper Dnieper, as a result of the assimilation of the local population by Indo-Europeans, formed Balts. This is evidenced by the Baltic hydronymy(Luchesa, Polota, Losvido). The Balts brought the Bronze Age to Belarus. Baltic-speaking tribal groups appeared substrate(the basis) of Belarusian ethnogenesis.

With the settlement of the Indo-Europeans, not only the ethnic composition of the population of Belarus changed, but the era also changed. The Stone Age gave way to the Bronze Age (3 - 2 thousand BC - 1 thousand BC). The ancient economy, based on fishing, hunting and gathering, was gradually replaced by agriculture and pastoralism. The Indo-Europeans practiced plow farming. A plow of a well-known design, which has come down to us in drawings of that time, was found in a peat bog near the village of Kaplanavichy in the Kletsk region.

The Indo-Europeans worshiped fire and the sun. Fire was given the significance of cleansing power, and the color red was associated with it. A manifestation of the cult of fire was the custom of sprinkling the body of the deceased with mineral red ocher, which was then transferred to the bones, and during excavations it seems as if the bones were specially painted.

The activity of the Indo-Europeans is associated with the ornament used to decorate the dishes - imprints of a cord wound on a stick. Such an ornament was called corded, and the archaeological culture was called the culture of corded ceramics. Its distribution areas covered vast territories of Europe, including the lands of Belarus. From the middle of the Bronze Age, the territory of Belarus entered the area of the Middle Dnieper, Vistula-Neman, Corded Ware Polesie cultures, as well as the North Belarusian ones.

The use of more efficient bronze tools and advances in agriculture and animal husbandry created conditions for the accumulation of knowledge by individual families, which was tempting for others. Robberies and robbery became one of the forms of enrichment. Therefore, the main type of Baltic settlements were fortified settlements, of which there were about 1 thousand on the territory of Belarus. According to archaeologists, an average of 50 to 75 people lived on one settlement. The total population in the Bronze Age could range from 50 to 75 thousand people. With the development of agriculture, the settlements changed into open settlements-villages, where several large and then small families lived.

It should be noted that the Neolithic population of Belarus was not completely assimilated. The old economic and cultural traditions still existed. Some regions of Belarus were sparsely populated by Balts. But on most of its territory the Baltic ethnic group was formed. This is evidenced by the fact that the vast majority of river names (Verkhita, Volcha, Gaina, Grivda, Drut, Klevo, Luchesa, Mytva, Nacha, Palata, Ulla, Usyazha, Esa, etc.) retained the roots and characteristic endings that are in Lithuanian and Latvian, i.e. Baltic languages. We can recall other names related to Baltic hydranonymy: Osveya, Drisvyaty, Losvido, Muysa, Naroch, Usvyacha, etc. The most common hydronyms associated with the Balts are in the basins of the Berezina (Mena, Olsa, Seruch, Usa) and Sozha rivers (Rekhta, rest, Snov, Turosna).

The origin of the term “Balts” is associated with the Latin name of the island in northern Europe (vasha, Vaisia), which was described by Pliny the Elder (1st century AD). Words with the root “Balts” are found in the German chronicler Adam of Bremen (IIst.), in Prussian chronicles, Old Russian and Belarusian-Lithuanian chronicles of the 14th – 16th centuries. The term “Balts” was introduced into scientific use by the German linguist G. Neselman in 1845.

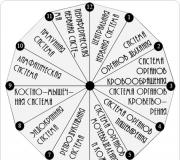

On the territory of Belarus in the Iron Age (1 thousand BC - IV-V centuries AD) several archaeological cultures were formed: Dnieper-Dvina (in the north), the culture of hatched ceramics (middle and northwestern parts of Belarus), Milograd and Zarubinets (in the south of Belarus). Iron Age cultures were quite developed. Local tribes mastered iron processing; iron products were quite diverse: axes, knives, sickles, weapons, jewelry, etc.

Thus, the Baltic stage of the ethnic history of Belarus is the time of the spread of Indo-Europeans on the Belarusian lands with their main occupations - agriculture and cattle breeding, a time of intensive assimilation of the local Neolithic population, including the Finno-Ugric ones in the north of Belarus. The local Neolithic population gradually transformed into the Indo-European Balts, while simultaneously exerting a certain influence on their language and culture.

9. Founded non-Slavic tribes on Belarusian lands.

It was previously noted that by the VI – VII centuries. in most of the territory of Belarus the Baltic population predominated. The Slavs at that time lived compactly, in a continuous massif only in the Pripyat basin, mainly to the south of it. The main type of Slavic settlements were settlements (unfortified settlements), and the type of housing was semi-dugouts.

In the 6th – 7th centuries. The penetration of the Slavs into the Baltic area began. The Balts have half-dugouts with heater stoves, stone millstones, iron knives and other Slavic things and tools.

In the VIII – IX centuries. There is a massive settlement of Slavs in the Baltic area on the territory of Belarus - first in the upper reaches of the Sluch and Ares rivers, on the right bank of the Dnieper, then on the Berezina. Burials according to the Slavic ritual by burning the body, as well as Slavic ceramics, were found in the mounds. The settlement came from the southern part of the Pripyat basin. The Slavs penetrated into the Dnieper and Podvinia regions in the 9th century, and by the 10th century. they settled in Upper Ponemonie. Moreover, part of the Baltic population was assimilated, the second was destroyed or driven out to the North-West, to the Baltic states, where it took part in the formation of ethnic Lithuanians and Latvians. A third of the Baltic population continued to live in their former places. The assimilation of this part of the Balts by the Slavs on the territory of Belarus continued until the 12th – 13th centuries. and even later.

As a result of the Slavic-Baltic synthesis in the 8th – 10th centuries. New ethnic Slavic societies emerged, which are often mentioned in medieval written sources. These are Dregovichi, Radimichi, Krivichi.

Dregovichi occupied most of Southern and a significant part of Central Belarus. The Tale of Bygone Years notes that they lived between Pripyat and the Western Dvina. Their culture was dominated by Slavic elements. The language was Slavic. However, in their culture of that time, Baltic elements were also recorded - spiral rings, snake-headed bracelets, horseshoe-shaped buckles. The custom of burying the dead in wooden coffins-towers dates back to Baltic origins.

The mixed origin of the Dregovichi as a result of the Slavic-Baltic synthesis is also reflected in the name of this community. Its root is apparently Baltic. In the Lithuanian language there are many words with this root (dregnas - damp, wet), which reflect one of the features of the area where the Dregovichi settled, namely the humidity, swampiness of the land in the Pripyat River.

Later, the Slavic “-ichi” was added to the base. Thus, term "Dregovichi" is a Slavicized name of the former, pre-Slovenian form, which meant a group of the Baltic population in accordance with the characteristics of the territory of residence. The origin of the word “quagmire” in the Belarusian language, which translated into Russian means “quagmire,” is also connected with the geographical feature of the Dregovichi territory.

Radimichi, according to information from the Tale of Bygone Years, occupied the lands between the Dnieper and the Desna. The main area of their settlement is the river basin. Sozh. Like the Dregovichi, the Radimichi were formed as a result of the mixing of the Slavic and Baltic populations, the assimilation of the latter. The culture was dominated by Slavic elements. The language was Slavic. At the same time, Baltic elements are also noted in archaeological sites: neck torcs, bracelets with stylized snake heads, beam buckles.

Chronicle legend about the origin of the Radimichi from a mythical personality Radzima reflects, in our opinion, more likely the biblical view of the author of this legend than the existence of a true person. Here we encounter an example of myth-making. According to a number of authors (N. Pilipenko, G. Khaburgaev), the term "radimichi" reveals affinity with the Baltic term “stay”.

Krivichi occupied the north of Belarus and neighboring areas of the Podvina and Dnieper regions (Pskov and Smolensk regions). They lived in the upper reaches of the rivers - Western Dvina, Dnieper and Lovat and were the largest East Slavic population. The Krivichi culture was divided into two large groups: Polotsk-Smolensk and Pskov.

The ethnic appearance was dominated by Slavic features. The language was Slavic. Baltic elements in the Krivichi culture include bracelets with snake heads, spiral rings, Baltic-type hryvnias, etc.

As for the name “Krivichi”, then there are several hypotheses. Some scientists (historian V. Lastovsky) derive the name “Krivichi” from the word “blood”; then it can be understood as “blood relatives”, “blood relatives”. The famous historian S. M. Solovyov argued that the name “Krivichi” is associated with the nature of the area that this community occupied (rugged, uneven - curvature). A large group of scientists (archaeologist P. N. Tretyakov, historian B. A. Rybakov, Belarusian philologist and historian M. I. Ermolovich) argue that the name of the pagan high priest was preserved in the name “Krivichi” Kryva-Kryveity.

In the first centuries AD, under the pressure of the Goths, who came from Scandinavia and landed at the mouth of the Vistula, the Slavs began their migration. As a result of the “great migration of peoples,” the Slavs were divided into three large groups: southern, western, eastern. The Slavic tribes that settled on the Balkan Peninsula became the ancestors of modern Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians, and Montenegrins. They mixed with the local Thracian and Illyrian populations, which had previously been oppressed by Byzantine slave owners. The West Slavic tribes, together with the population living on the banks of the Vistula, became the ancestors of the Polish, Czech, and Slovak peoples. Almost simultaneously with the Western and Southern Slavs, a third group emerged - the Eastern Slavs, the ancestors of modern Belarusians, Russians and Ukrainians.

Almost no written sources have survived about how and when the Slavs settled on the territory of Belarus. Therefore, scientific debates have not subsided to this day; there are different points of view and hypotheses on all these issues. Scientists draw their main data, with the exception of brief information about the settlement of the Slavs in the Tale of Bygone Years, from archaeological sources.

Archaeologists distinguish different cultures and identify them with certain ethnic groups. They note that in the south of Belarus monuments of Prague culture have been preserved (the culture of the early Slavic tribes, which in the 5th - 7th centuries AD inhabited the territory from the Dnieper and Lake Ilmen to the east and to the Elbe and Danube rivers to the west and south). Or, more precisely, its local variant - the Korczak-type culture (understood as the archaeological culture of the tribes that lived in the territory of northwestern Ukraine and southern Belarus in the 6th - 7th centuries AD). It is considered indisputable that these monuments belong to the Slavs.

On the main territory of Belarus and neighboring regions in the V - VIII centuries. Other tribes settled and left behind monuments of the so-called Bantser culture. It got its name from the settlement of Bantserovshchina on the left bank of the Svisloch. As for the identity of the Bantser culture, there is no consensus among scientists. Some consider it Baltic, others - Slavic. This happens because during excavations in the material culture signs of both Slavic and Baltic culture are discovered.

The supporter of the first hypothesis is the Russian archaeologist V. Sedov. He created the theory of the substrate origin of Belarusians. The Baltic substrate (from the Latin term - base, lining) refers to the ethnocultural population of the Baltic ethnic group, which influenced the formation of the Belarusian people. Proponents of this theory argue that as a result of the Slavicization of the Baltic population, the mixing of the Slavic with it, a part of the East Slavic people separated, which led to the formation of the Belarusian language and nationality.

Other researchers argue that, having settled in the territories previously occupied by the Baltic tribes, the Slavs partially pushed them back and partially destroyed them. And only small islands of the Balts, who probably submitted to the Slavs, were preserved in the Podvinya region, the Upper Dnieper region. But the Balts retained the right bank of the middle Poneman region and some parts of the territory between the Neman and Pripyat.

There is no clear generally accepted opinion among researchers on the formation of tribal unions, which formed the basis of the Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian ethnic groups. Some suggest that as a result of the intensive development by the Slavs of the territory of Belarus, where the Balts previously lived, in the 8th - 9th centuries. Ethnically close tribal unions have developed: Krivichi, Dregovichi, Radimichi, partly Volynians. On their basis, the Old Belarusian ethnos was formed. The Yatvingians and some other Baltic tribes took part in its formation.

The ancestors of the Eastern Slavs, who settled in Pripyat Polesie, assimilated the Baltic tribes. As a result, on the territory occupied by the Dnieper Balts, the East Slavic tribes Dregovichi, Krivichi, Radimichi - the ancestors of modern Belarusians - arose. On the territory where Iranian tribes used to live, the Polyans, Drevlyans, Northerners, and Volynians settled - the ancestors of modern Ukrainians. The assimilation of the Finno-Ugric tribes led to the emergence of the Novgorod Slavs, Vyatichi, and partly the Upper Volga Krivichi - the ancestors of modern Russians.

Proponents of a different point of view imagine this picture somewhat differently. Firstly, they believe that supporters of the above hypothesis exaggerate the role of the Balts in the ethnogenesis of the Belarusians. Another thing, they note, is the Middle Poneman region, where the Balts made up a significant part of the population at the beginning of the 2nd millennium. In the Slavicization of these lands, a significant role belongs to the Volynians, Dregovichs, and, to a lesser extent, the Drevlyans and Krivichi. They recognize that the basis of the Old Belarusian ethnos were the Krivichi, Dregovichi, Radimichi, and to a lesser extent the Volynians, most of whom participated in the ethnogenesis of the Ukrainians. They prove that both part of the Volynians took part in the formation of the Belarusians, and part of the Dregovichi - in the ethnogenesis of the Ukrainians. Radimichi equally participated in the formation of Belarusians and one of the groups of the Russian ethnic group. The Krivichi played a big role not only in the formation of Belarusians, but also in the formation of the northwestern part of the Russian ethnic group.

The main occupation of the population of the Belarusian lands was agriculture. The Eastern Slavs brought a more progressive form of agriculture - arable farming, but continued to use shifting agriculture. They sowed rye, wheat, millet, barley, and flax. Livestock farming played an important role. Families, united by a common economic life, formed a rural (neighboring) or territorial community. Cultivated land, forests and reservoirs were the property of the entire community. The family used a separate plot of communal land - an allotment.

In the IX - XII centuries. The Eastern Slavs developed a feudal system. In the beginning, the bulk of the population were free community members who were called “people.” Their social position gradually changed: some fell into a dependent position, while others remained relatively free. Dependent people were called “servants.” The servants included categories of the population deprived of personal freedom - serfs.

The formation of a class society is evidenced not only by the dependent position of a separate category of the population, but also by the presence of a squad. The warriors (or boyars) received from the prince the right to collect tribute from a certain territory. The collection of tribute from the free population of the territory that the prince “owned” was called polyudye. Gradually the tribute becomes feudal rent.

At this time, cities were formed. Some grew out of a fortified rural settlement like Polotsk, others like princely castles - Mensk, Grodno, Zaslavl. Still others arose along trade routes. The city consisted of parts: detinets, fortified with ramparts, ditches, walls; posada - a place where artisans and traders settled; and trading - places of sale and purchase of goods.

The Slavs professed a pagan religion. They believed in the god of the sun, fire, Perun, etc. The dead were buried in pits, with mounds built over them. They believed in an afterlife. Jewelry was worn from bone, copper, and ceramics.

Based on the characteristics of material culture monuments, the Upper Paleolithic is usually divided into the following time periods, named after the sites of classic finds for this period:

65--35 thousand years BC. Late Moustier;

35--25 thousand years BC. Aurignac;

25--20 thousand years BC. Solutre;

20--10 thousand years BC. Madeleine.

There are quite a lot of finds from the Upper Paleolithic - Neolithic era to see their significance in the spiritual quest of ancient man.

The Aurignac burials of the Cro-Magnon man have a new interesting detail for us. The bottom of the graves was sprinkled with ocher in advance. The body of the deceased was again sprinkled with ocher, covered with mammoth shoulder blades, and only then covered with earth. Ocher is very often, almost universally used by Cro-Magnon people both in funeral rituals and in other religious rites. It symbolizes blood, life and, in the words of religious scholar E.O. James, “expresses the intention to revive the dead through connection with a substance having the color of blood” Quoted. by: Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997, P. 65. It is possible that it was this custom that laid the foundation for the stable association of the “other world” with the color of blood in many religious traditions.

The discovery of ungulate horns and mammoth tusks in Late Neolithic graves becomes more common than in Neanderthal burials. This symbolism, widely known in human culture, must have meant the presence of a divine cover over a person. To testify not just to the hope of the resurrection, but to the hope of the resurrection in a better divine world than this.

The dead were believed to be wearing clothes embroidered with shellfish, which were not very comfortable to wear. Apparently, we are dealing with a specially made funeral vestment. Women, children, and even newborns were buried this way.

But not all burials have such a solemnly calm character. In complete contrast to them are the finds of bodies bound after death, sometimes devoid of any funeral gifts; people buried face down under a pile of heavy stones; dismembered corpses.

According to the method of the historical-phenomenological school, it can be assumed that they were thrown into a pit without vestments, without proper burial, with their hands and feet tied, not out of fear that the deceased would get up, but wanting to depict how the criminal would be dealt with at the afterlife trial. The body of the sinner became a kind of icon of the torment and death of his soul in another existence, and, at the same time, since the image and the prototype, the body and the personality, most likely, were not completely separated according to the ideas of the ancients, it was supposed to intensify the suffering of the soul, deprived of divine bliss and resurrection.

Did the Aurignacian mammoth hunters think so, or were they guided by other motives, solemnly burying some of the dead and “executing” the bodies of others, but one thing is clear - “The people of the last Ice Age buried their dead in the unconditional confidence of their future bodily life. They also seemed to believe that some kind of life continued to last in the bodies of the dead.” Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P. 68., writes J. Maringer.

If Cro-Magnon hunters were not convinced of the resurrection of their dead, they would certainly not have attached such importance to the funeral ritual and the preservation of their physical remains. Simple experience certainly showed them that such a resurrection would not come soon. The bones of our ancestors continued to decay in the ground, despite the ocher, mammoth tusks and cowrie shells. And the fact that this did not discourage the ancient hunters, did not cultivate disbelief in them, makes us assume that the Cro-Magnons are the ancient people who created this archaeological culture. They expected victory over death not soon, but in the distant future, when all their ritual efforts would bring the priceless fruit of a full bodily resurrection.

Communication with the deceased. But the expectation of the resurrection of the dead did not mean for the Cro-Magnon man their complete disappearance from the lives of the living before the arrival of this hoped-for moment. Although the bones of the dead lay in their graves, their souls and powers remained part of the tribe and took some part in life. We can guess that Upper Paleolithic hunters thought this way from some strange, at first glance, finds. These are the so-called howler monkeys, horn products with a dominant three-part symbolism. Applying the method of comparison with the practice of modern ahistorical peoples, it can be argued that they were used to communicate with their ancestors. When a howler monkey is touched with special objects (a comb, the skin of a totem animal), it makes sounds in which the natives hear the voices of their ancestors. Traces of ocher have been preserved on the howler monkey from La Roche, which certainly indicates the connection of the object with the funeral ritual and the other world.

For the most part, Upper Paleolithic people buried their dead, but sometimes they kept skulls in the dwellings of the living or in special sanctuaries. A drinking cup was made from the skull. Followers of the Chicago school tend to interpret these facts as follows: “... the skull, which was the seat of the brain, retains some kind of spiritual, invisible content, some piece of the personality of the deceased, which the living can share. For the Cro-Magnons, the material remains of the deceased were not insensitive dust, but one of the elements, one of the constituent parts of their deceased relative, remaining in their world, so that with its help they could enter into communication with the departed into another existence. This part kept something of the personality of the deceased; it was a symbol of the deceased person. But, as in the case of other symbolic images, here he retained the qualities and powers of the prototype, the deceased ancestor himself. The funeral ritual of the Cro-Magnons, in which, judging by the ocher remains in them, bowls made from skulls were used, further strengthened this connection and made the deceased ancestors part of the world of the living.” Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P. 71..

Religious meaning of Upper Paleolithic painting. Upper Paleolithic painting was discovered in 1879 by the Spanish nobleman Marcellino de Satuolo. At first it seemed self-evident that a sense of beauty simply awakened in a person, and he began to create with inspiration. “Art for art’s sake” was the motto of that time in culture, and this view was decisively transferred 20-30 thousand years into the past, attributing it to Cro-Magnon. In the 20th century, these finds began to be interpreted differently. At the beginning, it was noted that both in the paintings of caves and in the sculptures of animals found later, sculpted at the same time, a considerable number of subjects consist of hunting scenes, or rather, images of animals struck by arrows, spears and stones, sometimes bleeding. And although they were numerous, such subjects were far from dominant in cave art. By the end of the 1930s, paleoanthropologists agreed that the motivation for Cro-Magnon art was sympathetic magic, that is, the belief that by depicting an animal struck by an arrow before a hunt, one can confidently hope to hit it in the coming hunt.

The assumption was based on ethnographic data. Some primitive tribes, for example the pygmies, before a hunt actually draw on the sand the animal they are going to kill and at dawn on the day of the hunt, with the first rays of the sun, they hit the image with a hunting weapon, reciting certain spells. The hunt after this, as a rule, is successful, and the animal is struck exactly in the place where the spear pierced in the picture. But after the hunt is completed, the drawing is never saved. On the contrary, the blood (that is, the life-soul) of a killed animal is poured onto it, and then the image is smoothed out with a bunch of hair cut from the skin.

Despite the seemingly complete similarity between the hunting magic of the Pygmies and the monuments of Paleolithic painting, very important differences are immediately noticeable. Firstly, most of the animals still remain unaffected in the cave “frescos”; often the artist carefully depicts their peaceful life, loves to depict pregnant females and animals during mating games (however, with enviable bashfulness). Secondly, the images are made “for centuries” with the most durable paints using a long and very labor-intensive manufacturing technology. For the pygmy sorcerer, it is important to depict an animal, hit it, then, pouring blood on it, as if to restore life to the killed one. Afterwards, the image of the affected animal only interferes with its revival and is therefore immediately destroyed by the successful sorcerer. For some reason, the Paleolithic hunter did not at all strive to consider the matter over after a successful hunt. His aspirations were of the opposite nature. Thirdly, as a rule, it is important for a sorcerer to bring his magic closer to the place and time of the event that he wants to influence. Wanting to kill an antelope, the pygmies “killed” its image at dawn on the day of the hunt, on the same ground and under the same sky, which were to witness their hunting art.

The artists of the Frankish-Cantabrian caves acted completely differently. They seemed to deliberately choose the darkest, hidden corners, often extremely difficult to access and, if possible, going deeper into the ground. Sometimes, after completion of the work, the entrance was sealed with a stone wall, completely preventing people from entering. Ancient artists, unlike their modern brethren, seem to have been completely devoid of professional ambition. They avoided working where their fellow tribesmen lived. The Cro-Magnons settled, as a rule, not far from the entrance to the cave, if they chose this type of dwelling, and painted away from the camps, in the hidden silence of the dungeons. But they especially loved to choose caves as galleries that were not at all suitable for habitation, where archaeologists never found any traces of the daily life of a Cro-Magnon man. The famous Lascaux cave (Lascaux. Dordogne, France), with its inaccessibility and dank conditions, turned out to be a particularly desirable place for the ancient artist.

A major expert in the field of Paleolithic painting, A. Leroy-Gourhan, pointed out its most interesting feature - “the exceptional uniformity of artistic content” - “the figurative meaning of the images seems to have not changed from the thirtieth to the ninth millennium BC. and remains the same from Asturias to the Don." The French scientist himself explained this phenomenon by the existence of “a single system of ideas - a system reflecting the religion of the caves” Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P.75..

This is the interpretation given by the phenomenological approach in religious studies: “Cro-Magnons learned to bury their dead in the ground. And if they sought to leave images deeper in the depths of the earth, then most likely these images are related not to this above-ground, but to that underground (infernal) world. They tried to hide the images from the eyes of casual viewers, and often from viewers in general - therefore, they were not intended for a person, or certainly not for every person. These were paintings intended for the inhabitants of the underworld, for the souls of the dead and the spirits of the underworld. Pictures of that hunting paradise where the ancestors went and in which they stayed in anticipation of the resurrection. Spirits, unlike living ones, cannot hit animals with arrows and spears, but they need the blood of sacrificial animals in order to lead a full (full-blooded) life there and help the inhabitants of this world. And that is why bleeding, dying animals are depicted in hunting scenes. These are eternally lasting sacrifices to the dead.” Ibid. P. 74..

The idea of God in the Upper Paleolithic. Among the finds belonging to the archaeological cultures of Aurignacian and Solutrian, mammoth bones abound. It makes no sense to hunt such a huge animal for purely utilitarian purposes. Meanwhile, mammoths were killed not as an exception, but regularly, as if the Cro-Magnon man could not do without them. There is even an opinion that this wonderful animal disappeared due to too close interest in it by ancient man. And this interest, it seems, was not so much gastronomic as religious. The mammoth was necessary for the Upper Paleolithic hunter in ritual.

It is noteworthy that modern pygmies of Tropical Africa never hunt an elephant simply for meat. This dangerous and difficult hunt for them is always associated with sacrifice. They consider the elephant to be the embodiment of the Supreme God, the spirit, and the patron of man. They apologize to him for killing him, the most delicious parts (for example, the trunk) are buried in the ground, and the meat is eaten with reverence, in the hope of communion with the highest Heavenly Power. The analogy of these rituals with the customs of the Cro-Magnon man was first seen by P. Werner Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P.80..

Apparently, for the ancient hunters of Europe, communication with a mammoth in sacrifice, the presence of mammoth tusks and bones in the grave, in the sanctuary was a sign of worship of God, communion with God. By giving their dead to the protection of That Being, whose symbol was the mammoth, the Cro-Magnons most likely hoped for the introduction of their dead to His properties of eternity and omnipotence.

The cult of the mammoth certainly dominated the Late Paleolithic of Eurasia, but the more ancient bear cults were not completely forgotten. Some tribes preferred them. In the Silesian cave, Hellmishhöchll, L. Zotz made an even more interesting discovery in 1936. Not far from the entrance, he discovered a specially buried head of a young (2-3 years old) cave bear along with the bones of a brown bear. The archaeologist noticed that the teeth of the cave bear were carefully cut down shortly before his death (the dentin on the saw cuts did not have time to fully recover). Tools from the Aurignacian archaeological culture were found in the skull. Soon after L. Zotz published this find, ethnologist W. Koppers suggested a modern analogy to Zotz's find. It turns out that the Gilyaks and Ainu of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands had a custom of the so-called “bear holiday” at the beginning of the 19th century. In winter, after the solstice, a 2- to 3-year-old bear specially bred in captivity is sacrificed after solemn rituals. He is believed to be a messenger to the great spirit and, according to the Ayons, he will intercede for the tribe with this spirit throughout the year and will especially help the hunters. It is noteworthy that shortly before the sacrifice, the teeth of the sacrificial bear are filed down “so that it does not cause harm during the festivities” Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P. 83..

But the preservation of the ritual among the Ainu and Gilyaks does not mean at all that the explanations of its essence have reached us unchanged. The inhabitants of the Kuril ridge and Sakhalin are not able to rationally explain why they are torturing an animal that is already doomed to sacrifice and, at the same time, highly revered in principle. This is probably a later speculation. The ritual of beating a bear, which appeared in the Upper Paleolithic, could not but have a clear and well-understood meaning for people at that time. Most likely, it was somehow connected with the idea of the Supreme Being suffering for the sins of people; it was a ritual reproduction of some divine event that happened “at the time of it” and was associated with the suffering of God.

However, neither the ancient cult of the bear, nor the antlers of deer and mammoth tusks in the graves of fellow tribesmen could, in the Upper Paleolithic era, completely calm the human soul yearning to go beyond the boundaries of this earthly and temporary world. In the Lascaux cave, we are greeted by some images that to this day have not been explained satisfactorily by anyone. To begin with, in the first hall a procession of various animals is “led” through the vaults by a strange three-meter creature. It has the tail of a deer, the back of a wild bull, and the hump of a bison. The hind legs resemble those of an elephant, the front legs of a horse. The head of the animal is similar to a person, and from the crown of the head there are two long straight horns, which do not exist at all in the animal world. This animal, according to a number of researchers, is a female with pronounced signs of pregnancy.

If the goal of the ancient artist was “hunting magic,” then he would never have depicted such monsters. After all, in order to kill an animal during a hunt, it is necessary, from the sorcerer’s point of view, to reproduce its image as accurately as possible, and then kill the image. Even if we agree (and this is very doubtful) that the dark spots on the skin of the monster from Lascaux are traces from the stones of a hunting sling, then it is unclear why the sorcerer had to try hard on the three-meter image, which occupies a central place among the images of the first hall, if the animal is all that you won’t find it in the hunting fields either. The combined animal images strongly argue against the explanation of Paleolithic art as “hunting magic.”

Most likely, both the creature described above and the so-called drawing “died in front of the Great Bison” from the next room reflect the idea of God in the Upper Paleolithic. About the last scene, A. Zubov writes: “Here, in this mysterious fresco from Lascaux, the most secret hope of Paleolithic people appears before us - hope for victory over death, and appears not in the form of elements of a funeral ritual, but in a symbolic image. The bison standing over the deceased was struck by what appears to be a heavy spear. He is both the giver of life and the sacrifice for life.” Zubov A.B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P. 88.. This idea may seem too complicated for the Aurignacian hunters, but let us remember that it is precisely with this idea of death and victory over death of the giver of life (Osiris in Egypt, Dumuzi in Sumer, Yama - in the Vedas) humanity enters religious history 4-5 thousand years ago. The idea of the unity of sacrifice, victim and donor is a very ancient idea.

The image on the palette from the Raimondon cave (France) coincides with the Lascaux fresco. Only here people sacrifice a bison, hoping, perhaps, through this sacrifice to unite with the prototype, with that great Being, whose symbol the bison was for the Cro-Magnon man. The palette certainly depicts a sacrifice. The head of a bison on the bones, already freed from meat, and two front legs, cut off and lying in front of the head. There are people on both sides of the bison. These are participants in the sacrifice, the sacrificial meal. One of them has something like a palm branch in his hand.

The Lascaux fresco and the Raimondon palette are two parts of a holistic picture of the religious hopes of Upper Paleolithic man. On the palette we see a sacrifice in the world of people, on the walls of the cave - the result (and at the same time the reason) of this sacrifice in the world of the gods, where man so desired to go after passing the boundary of earthly life. Often the animals for the sacrifice were interchangeable, but this did not change the meaning of the sacrifice.

Paleolithic Venus. Another circle of Upper Paleolithic finds that have a meaning that goes beyond the boundaries of this everyday life are numerous figurines, reliefs and drawings of women. The figurines of Paleolithic “Venuses”, mostly dating back to Aurignac, show that the interest in women thirty thousand years ago was very different from what it is today. The face, arms and legs are very poorly detailed in these figures. Sometimes the entire head consists of one lush hairstyle, but everything that has to do with the birth and feeding of a child is not only carefully described, but, it seems, exaggerated. All this indicates that Paleolithic Venus is the prolific mother of A.B. Zubov. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P.98..

The following interpretation is possible. Most likely, these “Venuses” were images of “Mother Earth”, pregnant with the dead, who were yet to be born again to eternal life. Perhaps the essence thus depicted was the race itself in its continuation from ancestors to descendants, the Great Mother, always giving birth to life. For the keeper of the clan, individual “personal” characteristics are not important. She is a womb forever pregnant with life, forever feeding her mother with her milk. It is unlikely that the thoughts of the ancients rose to high abstractions, but since they buried their dead in the ground, then they believed in their resurrection, and if they believed, then they could not help but worship Mother Raw Earth, who gives food, life and the revival of Teeth A .B. History of religions. Book one: Prehistoric and ahistorical religions. Lecture course. - M.: Planet of Children, 1997. P.93.. The worship of Mother Earth, so natural among agricultural peoples, in fact turns out to be older than agriculture, since the purpose of worship for ancient man was not the earthly harvest, but the life of the next century.

Epoch Upper Paleolithic is called the period from approximately 40 to 10 thousand years ago. In Africa, the “Late Stone Age” is usually distinguished, which has the oldest dates of 30-50 thousand years ago. and noticeably different technologically from the European and Asian Upper Paleolithic. Many Upper Paleolithic cultures were created by people belonging to the modern species Homo sapiens; the population of Europe at this time is often called Cro-Magnons (after the Cro-Magnon cave in France, where in 1868 important finds of human skeletons and tools of the Upper Paleolithic era were made).

Cro-Magnons in Europe and the Middle East coexisted with Neanderthals for at least 5 thousand years in a row; perhaps this stage can be extended even to 24 thousand years (the oldest dating for the Upper Paleolithic is 52 thousand years, the latest for Mousterian and Neanderthals is 28 thousand years, although both are sometimes disputed). Transitional cultures between Mousterian and Upper Paleolithic are Chatelperron, Uluzzo, Bachokir, Bohunich, Selet, which existed from 45 to about 30 thousand years ago. Some archaeologists believe that Upper Paleolithic cultures arose independently of each other from local Middle Paleolithic ones almost everywhere. This view of the problem of the place and time of the appearance of the Upper Paleolithic was especially widespread among Soviet archaeologists and now in regional archaeological schools. In this case, the mentioned cultures with characteristics of both the Mousterian and the Upper Paleolithic are considered stage-intermediate. Other archaeologists argue that Mousterian was displaced. Typically, the Mousterian layer at sites is sharply delimited from the Upper Paleolithic layer in cultural terms, and sometimes by a sterile layer. In addition, there are examples where the Upper Paleolithic layer is overlain by the Mousterian layer, which indicates their synchronicity. Upper Paleolithic features in later Neanderthal cultures have already been discussed.

On the other hand, individual Mousterian features are typical specifically for European Upper Paleolithic sites, but are absent in Africa; this fact can be interpreted as evidence of reverse influences - Mousterian on the Early Upper Paleolithic. It is necessary to mention that the oldest Upper Paleolithic of Europe was found in its eastern part, penetration Homo sapiens It probably came from the Middle East (where the Upper Paleolithic is even older) through the East European Plain and the Balkans to the west. For Upper Paleolithic people, a tendency towards long-distance migrations was typical (for example, some sites in the Baikal region are surprisingly similar to Eastern European ones in a whole range of characteristics).

In Africa, a smooth transition is found from the “Middle Stone Age” to the “Late” 50-30 thousand years ago. in the central regions, but there is no such smooth transition in Northern, Eastern and Southern Africa. Microlithization of tools occurs, and tips typical of the “Middle Stone Age” disappear. In many ways, the “Late Stone Age” of Africa resembles the Mesolithic of Europe, although much older.

Lecture 7 Upper Paleolithic

general characteristics The Upper Paleolithic period of its existence is much shorter and is determined by archaeologists to be between the 40th and 10th millennia BC. e. Until recently, the Upper Paleolithic was divided into more subdivided periods: Aurignac, Solutre and Madeleine, according to which further stages of the development of human society were classified. But although human culture at this time develops in similar ways, certain territorial differences are already emerging. Therefore, it is more correct to abandon the division of the Upper Paleolithic into cultures that has been in existence for a long time, which received their names from monuments found in France, and is now used in Western Europe. For all of humanity, it would be more correct to divide it into the early, middle and late periods of the Upper Paleolithic.

The time of the Upper Paleolithic was primarily marked by the appearance of the modern type of man, Homo sapiens, i.e. a reasonable person. Having replaced the Neanderthals, he completed the transition from animal to human, which lasted about two million years.

The differences between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens consisted not so much in the disappearance of many features of external structure inherited from animals, but in large changes in higher nervous activity. The man of this time thought more, and therefore acted much more successfully than his predecessors. The reason that caused the emergence of a new type of person must first of all be sought in the formation of the tribal community. The Neanderthal, who lived in his own group, not only did not seek rapprochement with his own kind from other groups, but, most likely, avoided it, and in the event of a collision with his own kind, he behaved hostilely. Exogamy arose within the clan, that is, a custom prohibiting marriage relations between members of the clan, which forced a person to build interclan connections.

The Upper Paleolithic era coincided in time with the last stage of glaciation, which pushed humanity (especially in those areas where the cooling was felt especially strongly) to the further development of labor activity. First of all, this development affected the production of tools and the method of processing them. The technique for producing blank plates remains the same. They are obtained by cleaving from a prismatic core. But due to the improvement of retouching, the tools became more advanced, and their efficiency in work increased. For retouching, they began to use bone sticks fixed in a wooden handle. Pressing the compound wringer, the master did not chip off the elastic bone tip, but rather whittled flint flakes from the tool blank one after another. This “sharpening” of the working part of the weapon was carried out not on one side, as was the case in previous eras, but on both sides, which increased the quality of the weapon.

Retouching was used not only to process the working edge of a tool; it was often used to process the entire surface of the product. The retouching technique was complex and required maximum attention from the master. It was enough not to calculate the pressure when pressing, and the flint could be split. This apparently happened often, as evidenced by numerous finds of tools damaged by the master during the manufacturing process. Retouching was also used to cover parts of tools that did not play a significant role in the labor process. Such a passion for retouching indicates the emergence of an aesthetic perception of things in a person. Man sought to make not only a convenient, but also a beautiful tool.

The time of the Upper Paleolithic was marked by the widespread use, along with stone tools, of tools made of bone: spear tips, darts and harpoons were mainly made from this material. The expansion of hunting equipment speaks quite clearly about the intensity of hunting.

To throw a spear, a person invents a spear thrower. The materials for its manufacture were wood and bone. Modern peoples who use spear throwers currently make them primarily from wood. Perhaps in those days they were more often made from wood, but since it is poorly preserved, archaeologists more often find bone spear throwers or made from reindeer antler. The latter include finds at Paleolithic sites in France: Bruniquel, Logerie Bass, Gourdan. The spear thrower allowed the hunter to increase the length of the spear's flight.

The role of hunting especially increased in areas close to the glacier, where there were fewer edible plants for human consumption. In these areas, herds of reindeer and musk ox grazed; a little to the south was the kingdom of the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and bison; Even further south, herds of wild horses, deer, antelope, etc. grazed. The possibility of rich prey attracted man, and he intensively moved north, exploring more and more new territories.

In areas where the influence of the next cold snap was not felt, the hunter of the Upper Paleolithic time hunted zebra, antelope, and elephant, but gathering, which in the northern regions came to almost nothing, plays a large role in human economic life.

In addition to bone tools intended for hunting and fishing, it is necessary to note the appearance of bone needles with a hole (eye) located in their thickest part, into which a tendon was pulled, acting as a thread. Bone needles were stored in special cases made from the tubular bones of birds. The appearance of needles indicates the existence of tailoring in the Upper Paleolithic era. True, a person could sew together individual parts of skins using simple punctures (bone and flint), but the presence of an eye simplified this process and undoubtedly contributed to more advanced production of various types of clothing. For a long time, scientists had no information about the presence of clothing among Paleolithic people. However, in Buryatia, at the Buret site, a bone figurine of a woman was discovered, made from mammoth ivory, wearing clothes with a hood on her head. Today, science has sufficient material to completely reconstruct the various types of clothing, hats, and shoes that make up the complete set of clothing of a person from the Upper Paleolithic era. One of the options was a warm suit made of fur, the length of which reached the ankles. On the head they wore a headdress in the form of a fur hood that folded back. The clothes were put on over the head, since there were no marks from longitudinal cuts on it, but for the harsh climate it was very comfortable. This clothing has survived almost unchanged among many peoples living in the Arctic regions to this day. Indicative in this regard are the finds of burials at the Sungir site (Vladimir region), where the deceased was covered with a huge amount of bone jewelry, the arrangement of which made it possible to reconstruct the costume of an Upper Paleolithic person.

It should be noted that figurines of a man in clothing dating back to the Upper Paleolithic are very rare. More often there are images of a naked person. Some researchers believe that people of those times obviously stayed naked or semi-naked in their homes. Clothes were used outside the home.

Archaeological cultures In the Upper Paleolithic, not only did population density increase, but also the human ecumene expanded. Based on climatic conditions, and therefore differences in the economic life of man during the Upper Paleolithic period, it is more appropriate to consider the cultural development of five territorial regions.

The first area is periglacial. This includes the middle zone of Western and Eastern Europe, northern and northeastern Europe, mountainous regions... By the time of the Upper Paleolithic, the vast territory of this region, thanks to climate warming, was quickly covered with forests. At first, spruce and pine trees grew in place of the retreating glacier, then, when the glacier retreated further, they were replaced by oak, hornbeam, linden, beech, i.e., broad-leaved trees.

In Western Europe, there are a number of cultures that either replace one another or coexist in different territories from 40 to 10 thousand years ago. The main ones are the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian cultures, or industries.

Seletskaya the culture developed at the beginning of the Wurm I-II interstadial or a little earlier. Many Mousterian features are preserved in material culture. Its early stage took place in a mild climate, while its advanced stage took place in a drier climate. The beginning of the seleto dates back to about 42 thousand years ago. Characteristic are the leaf-shaped tips of spears and darts, processed on both sides and made with flat retouching. Certain types of Mousterian tools are preserved, including leaf-shaped side scrapers.

Aurignacian industries are widespread from the Middle East (about 40 thousand years ago) to the western regions of Europe (from 37 to 30 thousand years ago), sometimes they live up to 20 thousand years ago. In Central Europe, Aurignacian industries had no local roots. According to the prevailing point of view, they advanced from the south, from the Balkan Peninsula. It is possible that they could have entered the Balkans from the Middle East. Aurignacian industries are characterized by types of tools such as end scrapers, various types of burins and drills, bone and horn tips of spears, darts and even arrows. According to a number of scientists, bows and arrows spread in Europe at this time. The bone tips of Aurignacian spears and darts are the first bone products to obtain a stable, permanently preserved form.

The creators of Aurignacian industries lived in small, rather isolated groups. These groups had hunting territories of less than 200 square meters. km each. Aurignacian sites are often found in river valleys, where they usually form groups. These include cave settlements in southern Belgium and southwestern France, and sites in the valleys of small rivers - tributaries of the Danube and Rhine.

For Gravettian industries are characterized by more diverse types of tools than Aurignacian ones. Gravettian tools are predominantly made from well-cut, usually quite small blades with extensive use of steep blunting retouch. Gravette dates mainly to the period 30-20 thousand years ago, but in some places it survives until the 13th thousand.

Hunting for the inhabitants of the tundra - mammoth and reindeer, cave bear, wolf, wild bull - was the main occupation of the Gravettian population in Central and Western Europe, and hunting for red deer predominated in Northern Italy. The hunt was of a specifically steppe nature. It is characterized by a fairly homogeneous prey composition and early specialization on certain animal species. Steppe hunting has reached a higher level than forest hunting. In the forests, people were forced to use a diverse set of weapons and were guided by a wide range of game. Steppe hunting led to a higher level of economic development - hence the emergence of more permanent settlements among the Gravettian population and the formation of the so-called semi-sedentary hunting society.

In Southwestern France, in the southern part of Central France, as well as in the Pyrenees, Catalonia and Asturias, they were widespread Solutrean industry. They date from 21 to 16 thousand years ago. Some scientists derive them from the Seletian ones, others believe that they moved here from North Africa. Typical products of Solutre are laurel and willow spearheads, side and end scrapers, and drills. In the Basque country, harsh, quite rugged, where there are no wide river valleys and coastal plains, the main hunting objects of the Solutrean population were chamois and mountain goats. In the vast open areas, hunting for red deer, horse, and bison predominated.

Madeleine industries characterize the latest period of the Upper Paleolithic and are distributed mainly in France, northern Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, the south of Germany, but the characteristic features of the Madeleine can be found throughout the periglacial region of Europe up to the Urals. Only Magdalenian impulses from the west penetrated into Central Europe, and the development itself took place on the basis of the Gravettian. In Eastern Europe, madeleine existed in a locally modified form.

Madeleine industries belong to the final phase of the last Wurm and the beginning of the post-glacial era and date back to 16-10 thousand years ago. The flint industry of Magdalenian cultures is dominated by flint burins, scrapers, and piercings; there are many antler and bone tools, including bone spearheads and harpoons.

One of the most striking monuments is the Sungir site in the Vladimir region. Children's burials were discovered here. The bones were stretched along a line from southwest to northeast. The children are aged seven and twelve years. The position of the corpse was unusual. Both children lay on their backs with their heads facing each other. Before this, this situation was known from a number of figurines. It is possible that this is a brother and sister who died of some disease at the same time. The young Sungir people were equipped with an amazing set of weapons in the amount of 16 items, among which were a club carved from mammoth bone (this kind of weapon was discovered for the first time), two spears - 2 m 42 cm and 1 m 66 cm, made from mammoth ivory. In addition to the listed items, there were also two sharp bone stiletto daggers measuring 42 and 28 cm. Bone darts also lay next to the buried people. Among the accompanying objects was the thigh of a cave lion (bones of this animal were also found in other sites at the site; they may have been used as decoration). A lot of jewelry was also made from bone. The graves in which the buried were placed were dug using hoes, also made of bone.

The Sungir people, who lived on the plain, had already created artificial dwellings. A thorough study of a large accumulation of mammoth bones and other animals in one of the areas of the Sungir site and a fire pit located inside the observed accumulation made it possible to restore the appearance of one of the buildings. The dimensions of this building were small; its diameter was no more than 3 m. Its frame was made up of wooden poles and bones of large animals. The frame was covered on top with animal skins. A fire burned in the center of the room, warming people on long autumn and winter evenings. In addition to this kind of dwellings, the Sungir people also had other buildings that looked like a hut made of poles and branches.

Finds in the Kostenkovo-Borshevsky archaeological region on the Don (not far from Voronezh) made it possible to most fully restore the life of the people of the Upper Paleolithic. The people who lived in this area were amazing mammoth hunters and serious builders. The area of one of the dwellings excavated here reached almost 600 sq.m. Its length was 35 m, and its width was 15-16 m. Along its central axis there were 9 hearths, the diameter of which reached 1 m. The hearths were located at a distance of up to 2 m from each other. This huge dwelling was the main one for the members of society who lived on the site. Analysis of the ashes and burnt bone remains suggests that the fuel was mainly animal bones.

Not all lesions performed the same functions. So, in one, pieces of brown iron ore and spherosiderite were fired and a mineral paint - ocher - was obtained. Apparently, it was widely used, since traces of it were found on the entire surface of the floor. Near other hearths, archaeologists discovered tubular bones of a mammoth stuck into the ground. The characteristic notches and serifs on them suggest that they served as a kind of workbenches for the craftsmen working on them. In addition to this simple dwelling, there were three more. Two of them were dugouts located on the left and right sides of the main room. Both had fires. The frame of their roofs was constructed from mammoth tusks. The third room - a dugout - was located at the far end of the parking lot. The absence of a fireplace and any household items in it makes one think that this is a storage facility for food supplies and the most valuable products. Sculptural images of women and animals were hidden in special storage pits. Right there were decorations made from the fangs of predators. Other pits contained finished tools, for example, well-processed spear tips. It is not without interest that the figurines of women were deliberately broken. Archaeologists, comparing the available materials, came to the following conclusion: the settlement of Kostenki was abandoned by the owners shortly before the arrival of the enemies. The invaders, having discovered the figurines, smashed them, thereby destroying, according to their belief, the possibility of procreation of their enemies.

Similar dwellings were later discovered in Dolni Vestonica (Czechoslovakia). The dwelling is also slightly recessed into the ground, oval in plan, its length is 19 m, width 9 m. There were five hearths inside. Among the finds there are many flint tools, there are also tools made of bone, but the bone here was used mainly for jewelry. In Switzerland, similar structures were discovered in Schussenried. Everywhere, bones and skulls of large animals, mainly mammoths, served as building material for dwellings. In Gontsy (Ukraine), 27 skulls and 30 mammoth scapular bones were needed to build a dwelling. The frame of this house was formed by 30 tusks. But not all houses were built only from bones. There are traces of dwellings with a supporting structure of a series of wooden posts. They had a gable roof, and its frame was made using wooden slats.

In Czechoslovakia, at the sites of Tibava and Barka, archaeologists discovered traces of a number of pillars and supports, with the help of which, apparently, the sloping roof was supported. The walls of some dwellings of the noted era were sometimes made of rods and had the appearance of wattle fence. It is possible that their walls were covered with animal skins. The walls were supported by stone slabs, mammoth bones, and sometimes earth rollers.

To the south of the periglacial zone of Europe there was a second zone, which included the southern regions of Europe, North Africa, i.e. Mediterranean. During the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic era, the so-called Capsian culture, named after the discovered monument of this culture near the city of Gafsa (Kapsa) in Tunisia.

Along with hunting, gathering played an important role in the life of people in this zone. The main objects for this type of activity were edible shellfish and plants. The scale of consumption of mollusks, both river and sea, is eloquently indicated by accumulations of shells, often covering an area of several hundred square meters. The thickness of the layer of shells reaches two to three meters, and in some places reaches five. The areas filled with animal bones (the result of hunting) and mollusk shells (the result of gathering) sometimes exceed 10 thousand square meters.

Unlike the population of the periglacial regions, who lived sedentary lives and knew how to build houses, the southerners led a nomadic lifestyle. Climatic conditions did not require them to build houses, and if necessary, they quickly built light shelter huts to shelter them from the sun, wind and rain. The presence of natural shelters such as caves and grottoes made it possible to temporarily use them. Tools were made mainly of stone; bone was almost never used. Only the simplest type of awls were made from it. In stone processing, the population of this second region lagged significantly behind the inhabitants of the periglacial regions. Thus, the carriers of the Capsian culture did not know the method of pressing retouching, did not know how to make points using double-sided processing, and they did not have laurel tips. But they knew how to produce small flint plates - microliths, which served as dart tips. Some scientists believe that microliths also served as arrowheads, which means that the bow as a weapon was known to the Capsians. Other composite tools were also created using microliths. The base of such tools was wooden or bone. Small flint plates that made up the blade were inserted into a specially made slot in the base.

Pieces of ostrich egg shells were used as material for jewelry. They were given a certain shape, a hole was drilled for stringing on a core, and the surface was covered with thin carved lines. There are known examples of such plates with geometric patterns or with realistic images of gazelles, ostriches and other animals. Stringed on sinew, these pieces made necklaces and bracelets. Drilled sea shells and animal vertebrae also served as decoration.

It is difficult to talk about the clothing of the inhabitants of Africa and the Middle East of those times, and it is unlikely that there was any, except for loincloths. We know much more about the clothing of the inhabitants of the southern regions of Europe. In grottoes located in the vicinity of Menton (Italy), archaeologists discovered burials of the Upper Paleolithic era. People were buried in clothes made of leather and decorated with sea shells sewn onto it; they wore bracelets made of the same shells on their hands, and necklaces on their chests. As in the Sungir burial ground, the bodies were sprinkled with red mineral paint. The position of the deceased is not always elongated; it can also be flexed. In the Grimaldi caves (Italy) two skeletons were discovered: one of a man and the other of an old woman. Both skeletons were placed on the site of the extinguished fire in a crouched position, and with them inventory in the form of tools, weapons, and jewelry.

The main features of the Capsian culture are found in the Late Paleolithic layers of settlements in Palestine, Iraq, Asia Minor, Transcaucasia, Crimea and parts of Central Asia. Some sites in Georgia, such as Mgvimevi and Devis Khvrel, are especially close to the Capsian culture. Everywhere in these areas, the basis of the economy was hunting and gathering. The Capsians did not build permanent artificial dwellings.

The third region includes the central and southern parts of the African continent. This area has been poorly studied to this day. One of the features of the development of cultures in this area is their almost complete absence of features similar to those of the neighboring Capsian culture. This is all the more interesting because there are no significant natural barriers between both areas. It should be noted that the cultures of the first region (the periglacial region of Central Europe) and South Africa had common features. These common features were that the people who lived in the south of the African continent had flint laurel-leaf tips processed using squeezing retouching, which are completely absent from the people of the Capsian culture

The most significant and studied culture of the third area is the culture bambat. It got its name from the Bambat Cave in Southern Rhodesia. In addition to flint, the Bambat culture also used quartz crystals. When struck at a certain angle, this stone can produce flake plates that are not inferior in quality to flint ones. In economic life, hunting here played a greater role than gathering. Analysis of fire pits indicates a person’s prolonged stay in one place.

The fourth region includes the territories of Eastern Siberia, the central part of the Asian continent and China. Archaeological research in the basin of the Angara and Yenisei rivers showed that in the Upper Paleolithic era a person penetrated here who had significant cultural skills and was in many ways close to the culture of the population of the Russian Plain. This can be traced on the basis of archaeological materials obtained from the settlement of the Military Hospital, opened near the city of Irkutsk (this is the earliest period), as well as from the Buret site on the river. Hangar and the settlement of Malta on the river. Belaya (tributary of the Angara). The population living in these places hunted mammoth, reindeer, bull, and wild horse. Although gathering existed, it provided a small amount of food. Climatic conditions allowed for gathering only at certain times of the year, so it was seasonal. The inhabitants of Bureti, like the hunters of settlements in the periglacial regions of Europe, led a sedentary lifestyle and knew how to build dwellings. In plan, these dwellings looked like a rectangle with slightly rounded corners. The floor of the room is somewhat recessed into the ground. Along the edge of this depression, the femur and shoulder blade bones of the mammoth were buried in a vertical position. For better fastening, their lower part was wedged with smaller bones and limestone slabs. The supports supporting the roof were large mammoth bones and tree trunks. The roof covering was assembled from reindeer antlers. The entrance to the dwelling was a long narrow corridor, lined along the edges with symmetrically located mammoth femurs. The corridor had no ceiling. This entrance device protected the room from the cold. Inside the dwelling there were fireplaces from which accumulations of ash remained. Exactly the same dwellings were discovered at the Malta site.

The tools used by the people who lived in this area during the Upper Paleolithic era are reminiscent of Western European tools from the Mousterian era. here, a disc-shaped core and massive triangular-shaped plates, as well as pointed points of an archaic appearance, were widely used. The processing technique uses impact retouching. Along with this, the population of Central Asia knew both prismatic cores and a method for obtaining long knife-like plates with regular parallel edges from them. They also used miniature scrapers. The pointed tips of spears and darts had a shape similar to European laurel leaves.

In Europe during this period, composite tools had not yet been used, but archaeologists discovered them at the Siberian sites of Afontova Gora and Oshchurkovskaya. Unlike the tribes living in Europe, the tribes of the Asian continent, along with flint, gray and black stone, used quartzite, jasper slate, deposits of which are found on the banks of the Lena, Angara, and Yenisei rivers; in addition, bone was widely used to make tools. Harpoons, piercing awls, and needles for sewing clothes were made from it, and the shape and size of the needles remained almost unchanged. The bone was also used to make jewelry - necklaces, plates with ornaments made of solid holes, figurines of humans, animals, and birds. Examples of the jewelry art of the population of Siberia from the Upper Paleolithic era can be found in objects discovered in the complex of a child’s burial discovered in Malta. This burial testifies to the complexity of the worldview of man of that time, which was expressed in the emergence of a funeral cult. The child's body was buried in a slot-shaped hole dug in the floor of the dwelling. The skeleton was sprinkled with red ocher. Around the neck of the deceased was worn a necklace of approximately 120 large flat beads and seven pendants. All pendants - six middle ones and one central one - are decorated with drills. Pendants in the form of birds, shaped like a flying swan or goose, and one square with rounded corners were also placed in the grave. All jewelry is made from mammoth ivory. In the grave pit there were weapons made of bone and stone. A small tombstone made of stone slabs was built over the grave.