Character prototype. Analysis of historical and modern prototypes, analogues of creative sources Literary prototypes

PROTOTYPE

- (Greek prototypon - prototype) - a real person or literary character who served the author as a model for creating a character. P. can appear in a work under a real name (Pugachev in “The Captain’s Daughter” by A.S. Pushkin) or a fictitious name (the prototype of Rakhmetov in N.G. Chernyshevsky’s novel “What is to be done?” was P.A. Bakhmetyev). Often the author “focuses” the features of different people or groups of people in a literary hero (for example, Vasily Terkin in the poem of the same name by A.T. Tvardovsky is a collective image of a Russian soldier). However, not all characters in works of fiction have P..

Dictionary of literary terms. 2012

See also interpretations, synonyms, meanings of the word and what PROTOTYPE is in Russian in dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference books:

- PROTOTYPE in the Literary Encyclopedia:

a prototype, a specific historical or contemporary personality of the author, who served as the starting point for creating the image. The process of processing and typing the prototype Gorky defines... - PROTOTYPE in the Big Encyclopedic Dictionary:

(Greek prototypon - prototype) a real person who served as the author’s prototype when creating an artistic work... - PROTOTYPE in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, TSB:

(from the Greek prototypon - prototype), a real person, the idea of which served as the fundamental basis for the writer in creating a literary type, an image of a person - ... - PROTOTYPE

(Greek] prototype; a real person who served the author as a prototype of a literary type, as well as a literary type, an image that served as a model for another... - PROTOTYPE in the Encyclopedic Dictionary:

a, m. 1. Initial sample, prototype, advantage. a real person as a source for creating a literary image, a hero. P. Bazarova. 2. Prototype, ... - PROTOTYPE in the Encyclopedic Dictionary:

, -a, m. A real person as a source for creating an artistic image, a hero. P. Anna... - PROTOTYPE in the Big Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary:

PROTOTYPE (Greek prototypon - prototype), a real person who served as the author’s source when creating art. ... - PROTOTYPE in the Complete Accented Paradigm according to Zaliznyak.

- PROTOTYPE in the Popular Explanatory Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Russian Language:

-a, m. A real person who served the author as a prototype, a model for creating a literary or artistic work. ...For Raphael, Fornarina was enough, that is... - PROTOTYPE in the Thesaurus of Russian Business Vocabulary:

- PROTOTYPE in the New Dictionary of Foreign Words:

(gr. prototypon) 1) a real person or literary character who served as the author’s prototype for the creation of a literary type; 2) someone or something... - PROTOTYPE in the Dictionary of Foreign Expressions:

[gr. prototypon] 1. a real person or literary character who served as the author’s prototype for creating a literary type; 2. someone or something that is... - PROTOTYPE in the Russian Language Thesaurus:

1. Syn: prototype, prototype (book) 2. Syn: experienced ... - PROTOTYPE in Abramov's Dictionary of Synonyms:

see sample,... - PROTOTYPE in the Russian Synonyms dictionary:

archetype, face, layout, model, sample, original, prototype, example, ... - PROTOTYPE in the New Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language by Efremova:

m. 1) A person who served the writer as a source for creating a literary character. 2) The original appearance, form of something. organ or organism from which they developed... - PROTOTYPE in Lopatin’s Dictionary of the Russian Language:

prototype, ... - PROTOTYPE in the Complete Spelling Dictionary of the Russian Language:

prototype... - PROTOTYPE in the Spelling Dictionary:

prototype, ... - PROTOTYPE in Ozhegov’s Dictionary of the Russian Language:

a real person as a source for creating an artistic image, the hero of P. Anna... - PROTOTYPE in Dahl's Dictionary:

husband. , Greek prototype, initial, basic sample, truth. Prototypical, -typical, primitive, ... - PROTOTYPE in the Modern Explanatory Dictionary, TSB:

(Greek prototypon - prototype), a real person who served as the author’s prototype when creating artistic... - PROTOTYPE in Ushakov’s Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language:

prototype, m. (lit.). Prototype, original, initial sample; a real person who served the author to create a literary type, as well as a literary type, image, ...

An artistic image is a specificity of art, which is created through typification and individualization.

Typification is the knowledge of reality and its analysis, as a result of which the selection and generalization of life material is carried out, its systematization, the identification of what is significant, the discovery of essential tendencies of the universe and folk-national forms of life.

Individualization is the embodiment of human characters and their unique identity, the artist’s personal vision of public and private existence, contradictions and conflicts of time, concrete sensory exploration of the non-human world and the objective world through artistic means. words.

The character is all the figures in the work, but excluding the lyrics.

Type (imprint, form, sample) is the highest manifestation of character, and character (imprint, distinctive feature) is the universal presence of a person in complex works. Character can grow from type, but type cannot grow from character.

The hero is a complex, multifaceted person. He is an exponent of plot action that reveals the content of works of literature, cinema, and theater. The author, who is directly present as a hero, is called a lyrical hero (epic, lyric). The literary hero opposes the literary character, who acts as a contrast to the hero, and is a participant in the plot

A prototype is a specific historical or contemporary personality of the author, who served as the starting point for creating the image. The prototype replaced the problem of the relationship between art and a real analysis of the writer’s personal likes and dislikes. The value of researching a prototype depends on the nature of the prototype itself.

Question 4. Unity of the artistic whole. The structure of a work of art.

Fiction is a set of literary works, each of which represents an independent whole. A literary work that exists as a completed text is the result of the writer’s creativity. Usually a work has a title; often in lyrical works its function is performed by the first line. The centuries-old tradition of the external design of the text emphasizes the special significance of the title of the work. After the title, the diverse connections of this work with others are revealed. These are typological properties on the basis of which a work belongs to a certain literary genus, genre, aesthetic category, rhetorical organization of speech, style. The work is understood as a certain unity. Creative will, the author's intention, and thoughtful composition organize a certain whole. The unity of a work of art lies in the fact that

the work exists as a text that has certain boundaries, frames, i.e. end and beginning.

Same with thin. the work is also another frame, because it functions as an aesthetic object, as a “unit” of fiction. Reading a text generates images in the reader’s mind, representations of objects in their integrity, which is the most important condition for aesthetic perception and what the writer strives for when working on a work.

So, the work is, as it were, enclosed in a double frame: as a conditional world created by the author, separated from primary reality, and as a text, delimited from other texts.

Another approach to the unity of a work is axiological: to what extent it was possible to achieve the desired result.

A deep justification for the unity of a literary work as a criterion of its aesthetic perfection is given in Hegel’s Aesthetics. He believes that in art there are no random details unrelated to the whole; the essence of artistic creativity lies in creating a form that matches the content.

Artistic unity, consistency of the whole and parts in a work belong to the age-old rules of aesthetics; this is one of the constants in the movement of aesthetic thought, which retains its significance for modern literature. In modern literary criticism, a view of the history of literature as a change in types of art is affirmed. consciousness: mytho-epic, traditionalistic, individual-author. In accordance with the above-mentioned typology of artistic consciousness, fiction itself can be traditionalist, where the poetics of style and genre dominates, or individual-authored, where there is the poetics of the author. The formation of a new – individual-author’s – type of artistic consciousness was subjectively perceived as liberation from various kinds of rules and prohibitions. The understanding of the unity of a work also changes. Following the genre-stylistic tradition, adherence to the genre canon ceases to be a measure of the value of the work. Responsibility for the artistic principle is shifted only to the author. For writers with an individual author's type of artistic consciousness, the unity of the work is ensured primarily by the author's intention of the creative concept of the work; here are the origins of the original style, i.e. unity, harmonious correspondence to each other of all sides and depiction techniques.

The creative concept of a work, understood on the basis of the artistic text and non-fictional statements of the author, materials of creative history, the context of his work and worldview as a whole, helps to identify centripetal tendencies in the artistic world of the work, the diversity of the form of the author’s “presence” in the text.

Speaking about the unity of the artistic whole, i.e. about the unity of a work of art, you need to pay attention to the structural model of the work of art.

In the center is the artistic content, where the method, theme, idea, pathos, genre, image are determined. Artistic content is put into form - composition, art. speech, style, form, genre.

It is during the period of dominance of the individual authorial type of artistic consciousness that such a property of literature as its dialogical nature is most fully realized. And each new interpretation of a work is at the same time a new understanding of its artistic unity. Thus, in a variety of readings and interpretations - adequate or polemical in relation to the author's concept, deep or superficial, filled with educational pathos or frankly journalistic, the rich potential of perception of classical works is realized.

Methods: interactive method, teacher explanation, conversation, collective survey, testing, cooperative group work. For interactive learning, the location of the desk and students, I choose position No. 3, creating a cluster.

Lesson type : a lesson in “discovering” new knowledge

During the classes

Motivation for learning activities.

Greeting the teacher, checking students who are absent and present in class.

Guys, December is significant for many events.. What do you associate it with? (Children's answers: Happy New Year, happy birthday, happy President's Day of the Republic of Kazakhstan, happy Independence Day, happy religious holidays, happy Nativity Fast, happy beginning of winter, happy snow, happy winter holidays)

By the way, N.A. Nekrasov was born on December 10, 1821. (according to the new style), bore the name of the Wonderworker (Nikola the Winter - 12/19), wrote a poem about the events of 12/14/1825, died 12/27/1877. (old style).

(Against the background of the song “Road”)

“...Endless again road, that terrible one, which the people called the path of chains, and along it, under the cold moon, in a frozen wagon, she hurries to her exiled husbandRussian woman , from luxury and bliss to cold and curse”, - this is what the early 20th century poet K.D. Balmont wrote about the poem by N.A. Nekrasov, which we will consider today, in his article “Mountain Peaks” (1904).

What keyword did you hear? (Road)

What is the road for you? (The path to school, to life.)

Indeed, the road accompanies every person throughout his life.

II. Updating knowledge and fixing difficulties in activities.

Teacher's word . In Russian literature of the 19th century.road motif is basic. For Nekrasov, the road became the beginning of understanding the restless people's Russia. His road is “gay”, “cast iron”, “iron”, “terrible”, “trodden with chains”. And he’s driving along this road?.. (Russian woman).

Who, serving the great goals of the age,

He gives his life completely

To fight for a human brother, -

Only he will survive himself...

Poetry N.A. Nekrasova served “the great goals of the century.” This is the source of her immortality, her unfading strength. That is why she is close to us, people of another century, for her faith in the Motherland and man, her bright love of life and courage, her love for Russian nature. That is why at every meeting we rediscover Nekrasov, and his poems awaken in us high and good thoughts, help us understand the world and ourselves, make us more generous and responsive to everything beautiful. “Go into the fire for the honor of your fatherland, for your conviction, for your love...” All the love and all the thoughts of the poet belong to Russia, the Russian people, the peasantry, downtrodden, trampled into the mud, but spiritually not broken.

Conversation with students:

What is the main theme of N’s creativity?. A. Nekrasova? (The hard life of the Russian people)

What works of the poet are you familiar with?(“Uncompressed Strip”, “Peasant Children”, “Railroad”)

Why does an ordinary peasant woman evoke the poet’s admiration?(Hard work, patience, the ability to love, the ability not to get confused and act in a difficult situation.)

Who was the Russian woman for Nekrasov?(Nekrasov’s heroine is a person who was not broken by trials, who managed to survive. It is not without reason that even Nekrasov’s Muse is the “sister” of the peasant woman).

III . Identifying the causes of difficulties and setting goals for activities (setting learning goals)

The topic of our lesson“ Poem by N.A. Nekrasov “Russian Women” Artistic images and their real historical prototypes. The plots of two poems. Heroic and lyrical principles in poems.

What problems do you think we should solve in class to learn a new topic?

1. Find out what historical events formed the basis for writing the poem .

2. How Nekrasov portrayed the heroes; to whom he expressed his likes and dislikes;

3. What place does the poem occupy in modern literature?

ІІІ . Implementation of the constructed project.

The first task we need to figure out. What historical events formed the basis for writing the poem? .

For this lesson, your classmates have studied historical events and prepared material. Please come to the board. 4 pre-prepared students perform during a slide show.

Historical background .

Let's remember our lesson rules: (can be written on the board)

Let's not interrupt!

Let's answer briefly!

We value time!

Let's not get distracted from the given topic.

The ability to listen to others.

Guys, what about you?learnedabout the Decembrist uprising on December 14, 1825? (All presentations are accompanied by slide shows on topics)

1) Nikolaev Russia .

In November 1825 During a trip to the south of Russia, in Taganrog, Emperor Alexander 1 unexpectedly died. He had no children. His brother Constantine was supposed to inherit the throne, but during Alexander’s lifetime he secretly abdicated in favor of his younger brother Nicholas. After Alexander's death, Constantine's abdication was not announced. The troops and population were immediately sworn in to the new emperor. But he confirmed his renunciation of the throne. On December 14, 1825 re-oath was appointed. This day turned out to be one of the most terrible in the life of Emperor Nicholasfirst.

2 ) Decembrist revolt.

Several military units came to Senate Square, refusing to submit to the new king. They were all noblesthat issupport of the autocracy and supporters of serfdom. The Decembrists (as they would later be called) wanted, before the senators and members of the State Council took the oath, to force them to sign a “Manifesto” with demands: to eliminate the existing government, to abolish serfdom, to proclaim freedom of speech, religion, freedom of occupation, movement, equality before the law, and a reduction in prison terms. soldier service. But the plan could not be implemented. The uprising in St. Petersburg was suppressed within a few hours. 579 people were involved in the investigation. Five Decembrists: poet K.F. Ryleev, P.I. Pestel, S.I. Muravyov - Apostol, M.P. Bestuzhev - Ryumin, P.G. Kakhovsky were hanged in the Peter and Paul Fortress. More than a hundred sentenced to hard labor and settlement in Siberia. Prince Sergei Trubetskoy was elected leader of the uprising, but he did not appear on the square. During the investigation, he behaved courageously, thereby earning respect among his comrades.

3) Wives of the Decembrists . Eastern Siberia.

In July 1926, convicts began to be sent in small groups to Siberia towards the unknown, towards a hard labor fate. There, behind the mountains and rivers, they will lie in the damp earth, there, behind the fog of distance and time, their faces will melt, the memory of them will dissipate. This was the king's intention. In those days, the tsar forbade any mention of the Decembrists, and Russia cried for them, because almost every noble noble house lost either a son, or a husband, or a nephew. And how unpleasantly surprised the tsar was when he received petitions from women - the wives of the Decembrists - for permission to follow their husbands to Siberia. Under the guise of a liberal king was hiding a vengeful and cruel man: everything possible and impossible was done to stop women who wanted to divide, to alleviate the fate of their husbands sent to hard labor: prohibitions, threats, laws to deprive them of all rights of the state. But women, amazing Russian women, could not be stopped by any obstacles. N.A. Nekrasov created his work about the feat of these amazingly fragile and amazingly strong-hearted and faithful women. Eleven women who voluntarily followed to Siberia destroyed the king’s intentions. Prisoners were prohibited from correspondence. The wives of the Decembrists took on this responsibility. Through the letters they wrote to their relatives, as well as to the relatives of other convicts, they remembered the prisoners, sympathized with them, and tried to alleviate their lot.

The return of the Decembrists from exile in 1856 caused a wide response in advanced Russian society. The Decembrists spent thirty years in hard labor and exile. By the time of the amnesty in 1856, only nineteen of the exiled Decembrists remained alive. Before the return of the Decembrists and for the first time after their return, even mentioning them in the press was prohibited. Nekrasov was forced to talk with great caution about the Decembrists themselves and the events of December 14, 1825.

- Thank you guys for studying historical events and doing a good job. Please sit down.

2. The history of the poem . “Russian Women” is a poem about the courageous and noble feat of the wives of the first Russian revolutionaries - the Decembrists, who, despite all the difficulties and hardships, followed their husbands into exile in distant Siberia. They renounced the wealth and comforts of their usual life, all civil rights, and doomed themselves to the difficult position of exiles.

This dedication of the wives of the Decembrists, their spiritual strength, attracted the attention of the writer, especially since it was impossible to directly say or think about writing about the heroic courage of the Decembrists themselves due to censorship prohibitions.

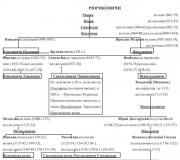

In 1869, he wrote the first of the poems in the cycle - “Grandfather” - about the Decembrist who returned as an old man from Siberian exile. The real prototype of the “grandfather” was Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Volkonsky, the husband of Maria Volkonskaya, the heroine of the poem “Russian Women”. This poem, written in 1871-1872, is one of the poet’s most significant works. It combines two poems that are closely related to each other by a common theme - “Princess Trubetskoy” and “Princess Volkonskaya”.

Fine. What is a poem? (A work of lyric-epic kind: a large lyric poem in which the plot (content) can be highlighted.

- Well done.WITHMake the necessary notes in your notebooks. N.A. Nekrasov is the first of the 19th century poets. turned to a topic that had been forbidden for many years - he spoke about the feat of the wives of the Decembrists. “Russian women” -poem-duology (consists of 2 parts united by a common theme) .

Speaking about the heroines of his poems, Nekrasov exclaimed:

Captivating images! Hardly

In the history of any country

Have you come across something wonderful?

Their names should not be forgotten.

The choice of topic is also connected with events deeply experienced by Nekrasov himself. Nekrasov’s friend N.G. Chernyshevsky and hundreds of other people were exiled to hard labor in Siberia.

1 hour “Princess Trubetskoy” (Ekaterina Ivanovna was the first to go to her husband in Siberia) was written based on “Notes of the Decembrist” by Rosen (1870), Trubetskoy, husband and son, published in 1872, with censorship distortions. Nekrasov himself welcomes her precisely because:

She paved the way for others

She inspired others to do great things! (This year, as you can see, the poem is being fulfilled 143 years )

2 hours “Princess M.N. Volkonskaya” written in 1872,published in 1873 (Maria Nikolaevna went to Siberia following Prince Trubetskoy) was written based on materials from “The Notes of M.N. Volkonskaya.” Nekrasov knew that Volkonskaya’s son kept notes from his mother, and he really wanted to read them. Having conceived the poem, Nekrasov persistently asked Volkonskaya’s son to give him “Notes”, citing the fact that he had much less information about Maria Nikolaevna than about Trubetskoy, and her image could turn out distorted. Mikhail Sergeevich Volkonsky, after a long refusal, finally agreed to read his mother’s notes to Nekrasov himself. For several evenings, Volkonsky read “Notes,” and the poet, while listening, made notes and notes. “Several times a evening,” recalls Volkonsky, “Nekrasov jumped up and with the words: “Enough, I can’t,” ran to the fireplace, sat down next to it and, clutching his head with his hands, cried like a child.”

According to the author, it was supposed to last 3 hours. - “Princess A.G. Muravyova” (Alexandra Grigorievna was the third female Decembrist).Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin sent through her his famous"MessageVSiberia", in which he expressed his ardent faith in future freedom. Who will tell an excerpt from the message?

Deep in Siberian ores

Keep proud patience

Your sorrowful work will not be wasted

And I think about high aspiration.

2. Second project: How Nekrasov portrayed the heroes; to whom did you express your likes and dislikes? .

Let's start to find out works at with text poems. Homework was to read a poem .

Who is the main character of the first part?(the heroine of the first part is Princess Trubetskoy)

- Who is Princess Trubetskoy saying goodbye to?(she says goodbye to her family)

- How does her father see her off?( The old count, Ekaterina Ivanovna's father, with tears puts the bear's cavity into the cart, which should take his daughter away from home forever)

- What does the heroine of the poem say to him goodbye?Read the 3rd stanza (O, God knows!.. But duty another,

And higher and more difficult,

He's calling me, forgive me dear!

Don't shed unnecessary tears!

My path is long, my path is hard,

My fate is terrible,

But I covered my chest with steel...

Be proud - I am your daughter !)

Underline the two main words on which the poem rests. Pride and duty are the two concepts on which the poem rests.

The poet compares each part of the text, what is compared, how does he achieve this? (dreams and reality, balls, trips abroad and reality, home and prison)

Why is “the princess-daughter going somewhere that night”? What makes her leave home and family?(duty and pride)

- But in order to fulfill their duty, women have to fight with those who prevent them from doing so.

And who is trying to stop them?(The king and the governor who carries out his will).

What's unusual about the poem? How does it resemble a dramatic work? How was it built?(This is a dialogue, but not just a conversation between two characters. This is a dispute, this is a confrontation, this is a struggle).

What is the central episode of this part of the poem?(Meeting of Princess Trubetskoy with the Irkutsk governor)

Why did the governor so not want the princess to travel further?(He received the strictest order from the king to restrain her by any means and not allow her to follow her husband).

How does the poem about Trubetskoy end? (ends with the scene of Trubetskoy’s victory over the governor)

Teacher: Nicholas the first, fearing that the noble deed of the Decembrist wives would arouse sympathy for them in society, gave instructions to prevent them in every possible way from carrying out their intentions. The wives of the Decembrists in Irkutsk had to sign a special document and renounce all civil rights. The text of this document is given in her notes by M.N. Volkonskaya (the text is projected on the screen)

« Here is the contents of the paper I signed:

§1. The wife, following her husband, continuing the marital relationship with him, will naturally become involved in his fate and will lose her previous title, i.e. will no longer be recognized as anything other than the wife of an exiled convict, and at the same time takes upon herself to endure everything that such a condition may have as a burden, for even the authorities will not be able to protect her from the hourly possible insults from people of the most depraved, contemptuous class who will find in it some right to consider the wife of a state criminal, who bears an equal fate with him, as their own kind: these insults can even be violent. Inveterate villains are not afraid of punishment.

§2. Children who take root in Siberia will become state-owned factory peasants.

§3. You are not allowed to take any money or valuable things with you...».

Teacher: Nekrasov did not strive for photographic accuracy or for sketching a historical portrait"DecembristOTo".For him"Decembrists"-first of all, progressive Russian women.

Questions can be distributed in the form of cards or conducted a frontal survey.

- Who is the heroine of the second part of the poem? (the heroine of the second part of the poem is Princess Volkonskaya)

- How does he show Volkonskaya at the beginning of the poem? (he shows Volkonskaya as a young and beautiful girl« queen of the ball » ) .

- What did Maria Nikolaevna have to give up to go to Siberia? (renounced her position in the world, her rich fortune, all rights and privileges, even her son)

- Who in Moscow inspires cheerfulness and faith in Maria Volkonskaya that her feat is not in vain? Read the passage of the poem expressively.

(The great Russian poet Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin admonishes her with beautiful words)

Go, go! You are strong at heart

You are rich in courageous patience,

May your fateful journey be completed peacefully,

Don't let losses bother you!

Believe me, such spiritual purity

This hateful world is not worth it!

Blessed is he who changes his vanities

To the feat of selfless love!...

How does Nekrasov paint the image of Volkonskaya in this parting word? (he paints a noble and bright image of Maria Volkonskaya herself)

That’s right, the heroines of the poem show themselves with spiritual purity and proud patience throughout their difficult journey.

What pictures of Russian life pass before Trubetskoy and Volkonskaya on the road? (on the road in front of her, as well as in front of Trubetskoy, there pass cruel and ugly pictures of oppression and poverty of the people)

How do mothers and wives see off recruits to military service in the poem? (they see off the recruits with bitter groans and tears)

Compare the farewell to the military service in our time with the tsarist time. (We see off our brothers to the army with the whole family, with a smile. We arrange an evening, gatherings, a festive dinner.)

How many years did you serve in the tsarist army, and how many are serving with us now? (They served in the tsarist army indefinitely, that is, all their lives, but in our time it’s only a year.)

How did these travel experiences affect Volkonskaya? (they filled Volkonskaya with indignation against the tsar’s arbitrariness)

For whom did she feel compassion and love? (She sympathized with and fell in love with the Russian people).

Did Volkonskaya fulfill her duty to her husband? (Yes, she did her duty)

What kind of heroic pathos do you think permeates the meeting with her husband when she, seeing her husband in chains, kisses them? (She kissed the shackles because she realized that her husband was a patriot of his homeland, and he wears these shackles for a reason).

Make a cluster. 1. Compare the images of Volkonskaya and Trubetskoy. What are their similarities? 2. Poem cluster.

Princess Volkonskaya

Princess Trubetskoy

N.A. Nekrasov

poem-duology

Let us summarize the second task: Nekrasov expressed his sympathies to the people, the Decembrists and Decembrists, they are the real heroes of the poem, and expressed his antipathies to the tsarist autocracy and serfdom.

Teacher: According to the latest third project. What place does the poem occupy in modern literature? we can say that the poem "Russian women"- one of the most striking works of Russian classical poetry.

The Decembrist uprising was suppressed, but the cause to which they devoted themselves did not pass without a trace. Nowadays on Senate Square in St. Petersburg there is a monument to the Decembrists, because their trace remained not only in history but also in the memory of the people. Since history is the memory of the people. (I show a modern photo of Senate Square on the slide)

І V . Summing up the lesson.

To summarize the lesson and check the strength of the material learned, I suggest answering the test.

Test.

1. What is main subject poems N.A. Nekrasova "Russian women"?

a) the fate of the Decembrists,

b) the greatness and fortitude of a Russian noblewoman

V) a story about the difficulties on the princess's way to Nerchinsk

d) the governor’s attempt to prevent the princess from supporting her husband

2. Highlight idea (main idea) of the poem

a) the tragic fate of a Russian woman,

b) denunciation of secular society,

V) spiritual greatness of the Russian woman,

d) feat of the Decembrists)

- Which problem sounds in the text?

A)The problem of choice, moral beauty, duty and honor, feat

b) debt problem .

c) love

d) patriotic feelings

- So, we have fully covered the topic of the lesson. “The spiritual and moral greatness of a woman in N.A. Nekrasov’s poem “Russian Women.”

Well done, you have mastered the topic and objectives of today's lesson. Thank you for participating.

I give ratings.

V . Homework. Instructing its implementation. Prepare to analyze the poem, complete creative tasks from pp. 124-125.

Character (actor)– in a prose or dramatic work, an artistic image of a person (sometimes fantastic creatures, animals or objects), which is both the subject of the action and the object of the author’s research.

In a literary work there are usually characters of different levels and varying degrees of participation in the development of events.

Hero. The central character, the main one for the development of the action, is called hero literary work. Characters who enter into ideological or everyday conflict with each other are the most important in character system. In a literary work, the relationship and role of the main, secondary, episodic characters (as well as off-stage characters in a dramatic work) are determined by the author's intention.

The role that authors assign to their hero is evidenced by the so-called “character” titles of literary works (for example, “Taras Bulba” by N.V. Gogol, “Heinrich von Oftendinger” by Novalis) . This, however, does not mean that in works entitled with the name of one character, there is necessarily one main character. Thus, V.G. Belinsky considered Tatyana an equal main character in A.S. Pushkin’s novel “Eugene Onegin,” and F.M. Dostoevsky considered her image even more significant than the image of Onegin. The title can introduce not one, but several characters, which, as a rule, emphasizes their equal importance for the author.

Character- a personality type formed by individual traits. The set of psychological properties that make up the image of a literary character is called character. Incarnation in a hero, a character of a certain life character.

Literary type – a character that carries a broad generalization. In other words, a literary type is a character in whose character the universal human traits inherent in many people prevail over personal, individual traits.

Sometimes the writer’s focus is on a whole group of characters, as, for example, in “family” epic novels: “The Forsyte Saga” by J. Galsworthy, “Buddenbrooks” by T. Mann. In the 19th–20th centuries. begins to be of particular interest to writers collective character as a certain psychological type, which sometimes also manifests itself in the titles of works (“Pompadours and Pompadours” by M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, “The Humiliated and Insulted” by F.M. Dostoevsky). Typification is a means of artistic generalization.

Prototype- a specific person who served the writer as the basis for creating a generalized image-character in a work of art.

Portrait as an integral part of the character structure, one of the important components of the work, organically fused with the composition of the text and the author’s idea. Types of portrait (detailed, psychological, satirical, ironic, etc.).

Portrait– one of the means of creating an image: depicting the appearance of the hero of a literary work as a way of characterizing him. A portrait may include a description of the appearance (face, eyes, human figure), actions and states of the hero (the so-called dynamic portrait, which depicts facial expressions, eyes, facial expressions, gestures, posture), as well as features formed by the environment or that are a reflection of the character’s individuality: clothes , manners, hairstyles, etc. A special type of description - a psychological portrait - allows the author to reveal the character, inner world and emotional experiences of the hero. For example, the portrait of Pechorin in the novel “Hero of Our Time” by M.Yu. Lermontov, portraits of heroes of novels and stories by F.M. Dostoevsky are psychological.

An artistic image is a specificity of art, which is created through typification and individualization.

Typification is the knowledge of reality and its analysis, as a result of which the selection and generalization of life material is carried out, its systematization, the identification of what is significant, the discovery of essential tendencies of the universe and folk-national forms of life.

Individualization is the embodiment of human characters and their unique identity, the artist’s personal vision of public and private existence, contradictions and conflicts of time, concrete sensory exploration of the non-human world and the objective world through artistic means. words.

The character is all the figures in the work, but excluding the lyrics.

Type (imprint, form, sample) is the highest manifestation of character, and character (imprint, distinctive feature) is the universal presence of a person in complex works. Character can grow from type, but type cannot grow from character.

The hero is a complex, multifaceted person. He is an exponent of plot action that reveals the content of works of literature, cinema, and theater. The author, who is directly present as a hero, is called a lyrical hero (epic, lyric). The literary hero opposes the literary character, who acts as a contrast to the hero, and is a participant in the plot

A prototype is a specific historical or contemporary personality of the author, who served as the starting point for creating the image. The prototype replaced the problem of the relationship between art and a real analysis of the writer’s personal likes and dislikes. The value of researching a prototype depends on the nature of the prototype itself.

- - a generalized artistic image, the most possible, characteristic of a certain social environment. A type is a character that contains a social generalization. For example, the type of “superfluous person” in Russian literature, with all its diversity (Chatsky, Onegin, Pechorin, Oblomov), had common features: education, dissatisfaction with real life, the desire for justice, the inability to realize oneself in society, the ability to have strong feelings, etc. d. Every time gives birth to its own types of heroes. The “superfluous person” has been replaced by the type of “new people”. This, for example, is the nihilist Bazarov.

Prototype- a prototype, a specific historical or contemporary personality of the author, who served as the starting point for creating the image.

Character - the image of a person in a literary work, which combines the general, repetitive and individual, unique. The author's view of the world and man is revealed through character. The principles and techniques for creating character differ depending on tragic, satirical and other ways of depicting life, on the literary type of work and genre. Literary character should be distinguished from character in life. When creating a character, a writer can also reflect the traits of a real, historical person. But he inevitably uses fiction, “invents” the prototype, even if his hero is a historical figure. "Character" and "character" - concepts are not identical. Literature is focused on creating characters, which often cause controversy and are perceived ambiguously by critics and readers. Therefore, in the same character you can see different characters (the image of Bazarov from Turgenev’s novel “Fathers and Sons”). In addition, in the system of images of a literary work, there are, as a rule, much more characters than characters. Not every character is a character; some characters only serve a plot role. As a rule, the secondary characters of the work are not characters.

Literary hero is an image of a person in literature. Also in this sense, the concepts “actor” and “character” are used. Often, only the more important characters (characters) are called literary heroes.

Literary heroes are usually divided into positive and negative, but this division is very arbitrary.

Often in literature there was a process of formalization of the character of heroes, when they turned into a “type” of some vice, passion, etc. The creation of such “types” was especially characteristic of classicism, with the image of a person playing a auxiliary role in relation to a certain advantage, disadvantage, or inclination.

A special place among literary heroes is occupied by genuine persons introduced into a fictional context - for example, historical characters in novels.

Lyrical hero - the image of the poet, the lyrical “I”. The inner world of the lyrical hero is revealed not through actions and events, but through a specific state of mind, through the experience of a certain life situation. A lyric poem is a specific and individual manifestation of the character of the lyrical hero. The image of the lyrical hero is revealed most fully throughout the poet’s work. Thus, in individual lyrical works of Pushkin (“In the depths of the Siberian ores...”, “Anchar”, “Prophet”, “Desire for Glory”, “I Love You...” and others) various states of the lyrical hero are expressed, but, taken together, they give us a fairly holistic picture of him.

The image of the lyrical hero should not be identified with the personality of the poet, just as the experiences of the lyrical hero should not be perceived as the thoughts and feelings of the author himself. The image of a lyrical hero is created by the poet in the same way as an artistic image in works of other genres, through the selection of life material, typification, and artistic invention.

Character - protagonist of a work of art. As a rule, the character takes an active part in the development of the action, but the author or one of the literary heroes can also talk about him. There are main and secondary characters. In some works the focus is on one character (for example, in Lermontov’s “Hero of Our Time”), in others the writer’s attention is drawn to a whole series of characters (“War and Peace” by L. Tolstoy).

Artistic image- a universal category of artistic creativity, a form of interpretation and exploration of the world from the position of a certain aesthetic ideal, through the creation of aesthetically affecting objects. Any phenomenon creatively recreated in a work of art is also called an artistic image. An artistic image is an image of art that is created by the author of a work of art in order to most fully reveal the described phenomenon of reality. At the same time, the meaning of an artistic image is revealed only in a certain communicative situation, and the final result of such communication depends on the personality, goals and even the mood of the person encountering it, as well as on the specific

Determining the prototypes of certain EO characters occupied both contemporary readers and researchers. In memoirs and scientific literature, quite extensive material has accumulated on attempts to connect the heroes of Pushkin’s novel with certain real-life persons. A critical review of these materials makes us extremely skeptical about both the degree of their reliability and the very fruitfulness of such searches.

It’s one thing when an artistic image contains a hint of a real person and the author expects that this hint will be understood by the reader. In this case, such a reference constitutes the subject of the study of literary history. It's a different matter when we are talking about an unconscious impulse or a hidden creative process that is not addressed to the reader. Here we enter the field of the psychology of creativity. The nature of these phenomena is different, but both of them are associated with the specifics of the creative thinking of a particular writer. Therefore, before looking for prototypes, you should first find out

484

First, was it part of the writer’s artistic plan to connect his hero in the minds of the readership with any real persons, did he want his hero to be recognized as this or that person. Secondly, it is necessary to establish to what extent it is typical for a given writer to base his work on specific individuals. Thus, the analysis of the principles of constructing a literary text should dominate the problem of prototypes.

This decisively contradicts the naive (and sometimes philistine) idea of the writer as a spy who “prints” his acquaintances. Unfortunately, it is precisely this view of the creative process that is reflected in a huge number of memoirs. Let's give a typical example - an excerpt from the memoirs of M. I. Osipova: “What do you think we often treated him to? Soaked apples, but they ended up in “Onegin”; Akulina Amfilovna, a terrible grumbler, lived with us as our housekeeper at that time. Sometimes we would all talk until late at night - Pushkin would want apples; so we’ll go and ask Akulina Pamfilovna: “bring , yes, bring pickled apples,” and she will get angry. So Pushkin once said to her jokingly: “Akulina Pamfilovna, come on, don’t be angry!” Tomorrow I will make you a priest." And sure enough, under her name - almost in “The Captain's Daughter" - I brought you out as a priest; and in my honor, if you want to know, the heroine of this story herself is named... We had a bartender, Pimen Ilyich, and he ended up in the story” (Pushkin in the memoirs of his contemporaries. T. 1. P. 424). A. N. Wulf wrote in his diary in 1833: “... I was even a character in the descriptions of Onegin’s village life, for it was all taken from Pushkin’s stay with us, “in the province of Pskov.” So I, a Dorpat student, appeared in the form of a Gottingen man called Lensky; my dear sisters are examples of his village young ladies, and Tatyana was almost one of them "(Ibid. P. 421). From the memoirs of E. E. Sinitsina: "A few years later I met in Torzhok near Lvov A. P. Kern, already an elderly woman, then they told me that this was Pushkin’s heroine - Tatyana.

...and everyone above

He raised his nose and shoulders

The general who came in with her.

These poems, they told me, were written about her husband, Kern, who was elderly when he married her” (Ibid. Vol. 2, p. 83).

These statements are just as easy to multiply as it is to show their groundlessness, exaggeration or chronological impossibility. However, the essence of the issue is not in the refutation of one or another of the numerous versions, which were then multiplied many times in pseudo-scientific literature, but in the very need to give the images of EO a flat biographical interpretation, explaining them as simple portraits of the author’s real acquaintances. At the same time, the question of P’s creative psychology, the artistic laws of his text and the ways of forming images is completely ignored. Such an unqualified, but very stable idea, which feeds a philistine interest in the details of biography and makes one see in creativity only a chain of

485

intimate details devoid of piquancy, makes one recall the words of P himself, who wrote to Vyazemsky in connection with the loss of Byron’s notes: “We know Byron quite well. They saw him on the throne of glory, they saw him in the torments of a great soul, they saw him in the tomb in the middle of resurrecting Greece. - You would like to see him on the ship. The crowd greedily reads confessions, notes, etc., because in their meanness they rejoice at the humiliation of the high, the weaknesses of the mighty. At the discovery of any abomination, she is delighted. He is small, like us, he is vile, like us! You’re lying, scoundrels: he’s both small and vile - not like you - otherwise” (XIII, -).

This could not be discussed if the real question of scientific and biographical interest about the prototypes of Pushkin’s images were not too often replaced by speculation about which of his acquaintances P “pasted” into the novel1.

Echoes of excessive “biographicalism” in the understanding of creative processes are felt even in quite serious and interesting studies, such as a series of investigations in a special Pushkin issue of the almanac “Prometheus” (Vol. 10. M., 1974). The problem of prototypes of Pushkin's novel is often considered with unjustified attention in useful popular publications.

In this regard, one can ignore arguments like: “Did Tatyana Larina have a real prototype? For many years, Pushkin scholars have not come to a common decision. The image of Tatiana embodied the traits of not just one, but many of Pushkin’s contemporaries. Perhaps we owe the birth of this image to both the black-eyed beauty Maria Volkonskaya and the thoughtful Eupraxia Wulf...

But many researchers agree on one thing: in the appearance of Tatiana the Princess there are features of the countess whom Pushkin recalls in “The House in Kolomna.” Young Pushkin, living in Kolomna, met the young beautiful countess in the church on Pokrovskaya Square...” (Rakov Yu. In the footsteps of literary heroes. M., 1974. P. 32. I would only like to note that based on such quotes, an uninformed reader may get a completely wrong impression regarding the concerns and activities of “Pushkin scholars.”

Speaking about the problem of prototypes of the heroes of Pushkin's novel, first of all, it should be noted that from this point of view there is a significant difference in the principles of constructing central and peripheral characters. The central images of the novel, which carry the main artistic load, are the creation of the author’s creative imagination. Of course, the poet's imagination is based on the reality of the impression. However, at the same time, it sculpts a new world, melting, shifting and reshaping life impressions, putting people in its imagination in situations in which real life denied them, and freely combining traits that are actually scattered across different, sometimes very distant characters. The poet can see in very different people (even

________________________

1 A kind of limit of this approach was B. Ivanov’s novel “The Distance of a Free Novel” (M., 1959), in which P is presented in the guise of an immodest newspaper reporter, bringing to public view the most intimate aspects of the lives of real people.

486

people of different sexes1) one person or several different people in one person. This is especially important for typification in EO, where the author deliberately constructs the characters of the central characters as complex and endowed with contradictory traits. In this case, one can talk about prototypes only with great caution, always keeping in mind the approximate nature of such statements. Thus, P himself, having met in Odessa a kind, secular, but empty fellow, his distant relative M.D. Buturlin, whom his parents protected from a “dangerous” acquaintance with the disgraced poet, used to say to him: “My Onegin (he had just started it then write), it’s you, cousin” (Buturlin. P. 15). Nevertheless, these words mean nothing or little, and in the image of Onegin one can find dozens of connections with various contemporaries of the poet - from empty social acquaintances to such significant persons for P as Chaadaev or Alexander Raevsky. The same should be said about Tatyana.

The image of Lensky is located somewhat closer to the periphery of the novel, and in this sense it may seem that the search for certain prototypes is more justified here. However, the energetic rapprochement between Lensky and Kuchelbecker, made by Yu. N. Tynyanov (Pushkin and his contemporaries, pp. 233-294), best convinces us that attempts to give the romantic poet in the EO some single and unambiguous prototype do not lead to convincing results .

The literary background in the novel (especially at the beginning) is constructed differently: trying to surround his characters with some real, rather than conventionally literary space, P introduces them into a world filled with persons personally known to both him and the readers. This was the same path that Griboyedov followed, surrounding his heroes with a crowd of characters with transparent prototypes.

The nature of the artistic experiences of a reader who follows the fate of a fictional character or recognizes an acquaintance in a lightly made-up character is very different. For the author of EO, like for the author of “Woe from Wit,” it was important to mix these two types of reader’s perception. It was precisely this that constituted that two-pronged formula for the illusion of reality, which determined simultaneously both the consciousness that the heroes are the fruits of the author’s creative imagination and the belief in their reality. Such poetics made it possible in some places of the novel to emphasize that the fate of the heroes, their future depend entirely on the author’s arbitrariness (“I was already thinking about the form of the plan” - 1, LX, 1), and in others -

________________________

1 In this sense, more than speculation about which of the young ladies he knew P “portrayed” in Tatyana, the paradoxical but profound words of Kuchelbecker can give: “The poet in his 8th chapter is similar to Tatyana. For his lyceum friend, for a person who grew up with him and knows him by heart, like me, the feeling with which Pushkin is filled is noticeable everywhere, although he, like his Tatyana, does not want the world to know about this feeling” (Kuchelbecker-1 pp. 99-100). The subtle, although prone to paradoxes, Kuchelbecker, who knew the author closely, considered Pushkin himself to be the prototype of Tatiana of the eighth chapter! The insight of this statement was pointed out by N. I. Mordovchenko (see: Mordovchenko N. I. “Eugene Onegin” - an encyclopedia of Russian life // TASS Press Bureau, 1949, No. 59).

487

to present them as his acquaintances, whose fate is known to him from conversations during personal meetings and whose letters accidentally fell into his hands (“Tatyana’s letter is in front of me” - 3, XXXI, /). But in order for such a game between convention and reality to become possible, the author needed to clearly distinguish between the methods of typing heroes, who are the creation of the author’s creative imagination, and heroes - conventional masks of real persons. A real person as the initial impulse of the author's thought could exist in both cases. But in one way, the reader has nothing to do with him, and in the other, the reader had to recognize him and constantly have him before his eyes.

In the light of the above, the final verses of the novel should be understood:

And the one with whom he was formed

Tatiana's sweet Ideal...

Oh, Rock has taken away a lot, a lot! (8, LI, 6-8).

Is it necessary to assume here that the author let slip against his will, and, seizing on this evidence, begin an investigation into the case of hidden love, or to assume that the slip of the tongue is part of the author’s conscious calculation, that the author did not let slip, but “sort of let slip”? wanting to evoke certain associations in the reader? Are these poems part of the poet’s biography or part of the artistic whole of EO?

Breaking off the novel as if mid-sentence, P psychologically ended it with an appeal to the time when work on the first chapter began, resurrecting the atmosphere of those years. This appeal echoed not only the work of P of the southern period, but was also contrasted with the beginning of the eighth chapter, where the theme of the evolution of the author and his poetry was revealed. The reader found the development of this thought - a direct contrast between the “pompous dreams” of the romantic period and the “prosaic nonsense” of mature creativity - in “Excerpts from Onegin’s Travels”, compositionally located after the final stanzas of the eighth chapter and, as it were, making adjustments to these stanzas. The reader received, as it were, two options for the outcome of the author’s thought: the conclusion of the eighth chapter (and the novel as a whole) affirmed the enduring value of life experience and creativity of early youth - the “journey” said the opposite:

I need other paintings: I love the sandy slope,

In front of the hut there are two rowan trees, A gate, a broken fence, There are gray clouds in the sky, In front of the threshing floor there are piles of straw... (VI, 200)

These provisions did not cancel one another and were not a mutual refutation, but cast mutual additional semantic light. This dialogic correlation also concerns the question that interests us: at the end of the eighth chapter, the myth of hidden love, so important for “southern” creativity, was restored - one of the main components of the life posture of the romantic poet (“and the one with whom he was formed ...”).

488

The reader did not have to make an effort to remember the allusions to “nameless love” scattered throughout Pushkin’s work of the romantic period. The ghost of this love, resurrected at the end of the novel with all the power of lyricism, was encountered in the “journey” with ironic lines about “nameless suffering”, assessed as “pompous dreams” (VI, 2W).

We do not know whether P meant a real woman in the last stanza of the novel or whether this is a poetic fiction: for understanding the image of Tatyana this is absolutely indifferent, and for understanding this stanza it is enough to know that the author considered it necessary to recall the romantic cult of hidden love.

Precisely because the main characters of EO did not have direct prototypes in life, they extremely easily became psychological standards for their contemporaries: comparing themselves or their loved ones with the heroes of the novel became a means of explaining their own and their characters. An example in this regard was set by the author himself: in the conventional language of conversations and correspondence with A.N. Raevsky, P apparently called “Tatyana” some woman close to him (it was suggested that Vorontsov; for fair doubts about this, see: Makogonenko G P. The work of A. S. Pushkin in the 1830s (1830-1833). L., 1974. P. 74). Following this conventional usage, A. Raevsky wrote to P: “... now I’ll tell you about Tatyana. She took a lively part in your misfortune; She instructed me to tell you about this, I am writing to you with her consent. Her gentle and kind soul sees only the injustice of which you have become a victim; she expressed this to me with all the sensitivity and grace characteristic of Tatiana’s character” (XIII, 106 and 530). Obviously, we are not talking about the prototype of Tatyana Larina, but about transferring the image of the novel to life. A similar example is the name Tanya, under which N.D. Fonvizin appears in I.I. Pushchin’s letters to her and in her own letters to him. N.P. Chulkov wrote: “Fonvizina calls herself Tanya because, in her opinion, Pushkin based his Tatyana Larina on her. Indeed, in her life there were many similarities with Pushkin’s heroine: in her youth she had an affair with a young man who abandoned her (though for different reasons than Onegin), then she married an elderly general who was passionately in love with her, and soon met the former object of her love, who fell in love with her, but was rejected by her” (Decembrists // State Literary Museum. Chronicles. Book III. M., 1938. P. 364).

The abundance of “applications” of the images of Tatiana and Onegin to real people shows that complex currents of communication flowed not only from real human destinies to the novel, but also from the novel to life.

It is impossible to exhaust the Onegin text. No matter how much detail we dwell on political hints, significant omissions, everyday realities or literary associations, commenting on which clarifies various aspects of the meaning of Pushkin’s lines, there is always room for new questions and for searching for answers to them. The point here is not only the incompleteness of our knowledge, although the more you work to bring the text closer to the modern reader, the more sadly

489

You become convinced of how much has been forgotten, and partly forgotten irrevocably. The fact is that a literary work, as long as it directly excites the reader, is alive, that is, changeable. Its dynamic development has not stopped, and for each generation of readers it turns into some new facet. It follows from this that each new generation turns to the work with new questions, revealing mysteries where before everything seemed clear. There are two sides to this process. On the one hand, readers of new generations forget more, and therefore what was previously understandable becomes obscure to them. But on the other hand, new generations, enriched by historical experience, sometimes bought at a heavy price, understand familiar lines more deeply. It would seem that poems that they have read and memorized suddenly open up to previously incomprehensible depths. The understandable turns into a mystery because the reader has acquired a new and deeper view of the world and literature. And new questions await a new commentator. Therefore, a living work of art cannot be commented on “to the end”, just as it cannot be explained “to the end” in any literary work.

In L.N. Tolstoy’s novel “The Decembrists,” a Decembrist woman who returned from Siberia, comparing her old husband with her son, says: “Seryozha is younger in feelings, but in soul you are younger than him. I can foresee what he will do, but you may still surprise me.” This can be applied to many novels written after Eugene Onegin. We can often foresee what they will “do,” but Pushkin’s novel in verse “may still surprise us.” And then new comments will be required.