What customs did the peoples of Siberia have? The world of Siberian old-timers: life, culture, traditions

The territory of Siberia can be called truly multinational. Today its population mostly represented by Russians. Starting in 1897, the population has only been growing to this day. The bulk of the Russian population of Siberia were traders, Cossacks and peasants. The indigenous population is mainly located in Tobolsk, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Russian population began to settle in the southern part of Siberia - Transbaikalia, Altai and the Minusinsk steppes. At the end of the eighteenth century, a huge number of peasants moved to Siberia. They are located mainly in Primorye, Kazakhstan and Altai. And after the construction of the railway began and the formation of cities, the population began to grow even faster.

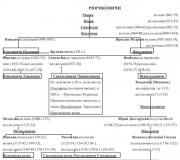

Numerous peoples of Siberia

Current state

The Cossacks and local Yakuts who came to the Siberian lands became very friendly, they began to trust each other. After some time, they no longer divided themselves into locals and natives. International marriages took place, which entailed mixing of blood. The main peoples inhabiting Siberia are:

Chuvans

The Chuvans settled on the territory of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. The national language is Chukchi, which over time was completely replaced by Russian. The first population census at the end of the eighteenth century officially confirmed 275 representatives of the Chuvans who settled in Siberia and 177 who moved from place to place. Now the total number of representatives of this people is about 1300.

The Chuvans were engaged in hunting and fishing, and had sled dogs. And the main occupation of the people was reindeer herding.

Orochi

— located on the territory of the Khabarovsk Territory. This people had another name - Nani, which was also widely used. The language of the people is Oroch, only the oldest representatives of the people spoke it, and besides, it was unwritten. According to the official first census, the Orochi population was 915 people. The Orochi were primarily engaged in hunting. They caught not only forest inhabitants, but also game. Now there are about 1000 representatives of this people.Entsy

Enets

were a fairly small people. Their number in the first census was only 378 people. They roamed in the areas of the Yenisei and Lower Tunguska. The Enets language was similar to Nenets, the difference was in the sound composition. Now there are about 300 representatives left.

Itelmens

settled on the territory of Kamchatka, they were previously called Kamchadals. The native language of the people is Itelmen, which is quite complex and includes four dialects. The number of Itelmens, judging by the first census, was 825 people. The Itelmens were mostly engaged in catching salmon fish; collecting berries, mushrooms and spices was also common. Now (according to the 2010 census) there are slightly more than 3,000 representatives of this nationality. Ket

Chum salmon

- became indigenous residents of the Krasnoyarsk Territory. Their number at the end of the eighteenth century was 1017 people. The Ket language was isolated from other Asian languages. The Kets practiced agriculture, hunting and fishing. In addition, they became the founders of trade. The main product was furs. According to the 2010 census - 1219 people

Koryaks

— located on the territory of the Kamchatka region and the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. The Koryak language is closest to Chukchi. The main activity of the people is reindeer husbandry. Even the name of the people is translated into Russian as “rich in deer.” The population at the end of the eighteenth century was 7,335 people. Now ~9000.

Muncie

Of course, there are still many very small nationalities that live on the territory of Siberia and it would take more than one page to describe them, but the tendency towards assimilation over time leads to the complete disappearance of small peoples.

Formation of culture in Siberia

The culture of Siberia is as multi-layered as the number of nationalities living on its territory is huge. From each settlement, the local people accepted something new for themselves. First of all, this affected tools and household supplies. The newly arrived Cossacks began to use reindeer skins, local fishing tools, and malitsa from the everyday life of the Yakuts in everyday life. And they, in turn, looked after the natives’ livestock when they were away from their homes.

Various types of wood were used as construction materials, of which there are plenty in Siberia to this day. As a rule, it was spruce or pine.

The climate in Siberia is sharply continental, which manifests itself in harsh winters and hot summers. In such conditions, local residents grew sugar beets, potatoes, carrots and other vegetables well. In the forest zone it was possible to collect various mushrooms - milk mushrooms, boletus, boletus, and berries - blueberries, honeysuckle or bird cherry. Fruits were also grown in the south of the Krasnoyarsk Territory. As a rule, the obtained meat and caught fish were cooked over a fire, using taiga herbs as additives. At the moment, Siberian cuisine is distinguished by the active use of home canning.

A new anthology on the history of Siberia

The Novosibirsk publishing house “Infolio-Press” is publishing “Anthology on the History of Siberia”, addressed to schoolchildren studying the history of our region independently or together with their teachers. The compilers of the manual are Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor of Novosibirsk Pedagogical University V.A. Zverev and Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Novosibirsk Institute for Advanced Training and Retraining of Education Workers F.S. Kuznetsova.

The anthology is part of the educational and methodological set “Siberia: 400 years as part of Russia,” intended for students of general education institutions. Earlier, in 1997-1999, a textbook by A.S. was published. Zuev “Siberia: Milestones of History”, as well as three parts of a textbook under the general title “History of Siberia” (authors - V.A. Zverev, A.S. Zuev, V.A. Isupov, I.S. Kuznetsov and F. S. Kuznetsova). “History of Siberia” has already gone through its second mass edition in 1999-2001.

“Anthology on the History of Siberia” is a textbook that helps create a full-fledged national-regional component of education in grades VII-XI in Siberian schools. But it does not contain ready-made answers to problematic questions. This is a collection of legislative acts, bureaucratic reports, materials of administrative and scientific surveys, excerpts from the memoirs of Siberian city dwellers and literate peasants, writings of travelers and writers. Most of these people were eyewitnesses and participants in the events that took place in Siberia in the 17th - early 20th centuries. Other authors judge Siberian history by the material remains of past life, by the written, oral, and visual evidence that has reached them.

The texts of the documents are grouped into eight chapters according to the problem-chronological principle. Taken together, they give the reader the opportunity to form their own idea of the past of the region and answer important questions that interest many Siberians. What peoples lived on the territory of our region in the 17th-18th centuries and why are some of them impossible to find on a modern map of Siberia? Is it true that the Russian people, having settled in Northern Asia, over time adapted so much to the local natural features and mixed so much with the indigenous inhabitants that by the middle of the 19th century. formed a completely new “Chaldonian” people? Was Siberia far behind European Russia in its development by the beginning of the 20th century? Is it appropriate to say that it was “a country of taiga, prisons and darkness,” a kingdom of “semi-savagery and real savagery” (these are assessments that were expressed in Soviet times)? What achievements of our Siberian great-grandfathers “grew Russia” in the old days and what can we, today’s Siberians, be proud of in the historical heritage of our ancestors?

The compilers of the anthology tried to select evidence in such a way that it would highlight the state of traditional folk culture, everyday life and customs of Siberians - “indigenous” and “newcomers”, villagers and townspeople. By the end of the 19th century. established orders began to crumble, unusual innovations penetrated the culture and way of life. The modernization of society that began then was also reflected on the pages of the anthology.

To understand the problems of a particular chapter, you must read the introduction placed at the beginning of it. Such texts briefly characterize the significance of the topic, talk about the main assessments and judgments existing in historical science and in the public consciousness, and explain the principles of selecting materials.

Before each document there is a short information about the author and the circumstances of the creation of this text. After the document, the compilers placed questions and tasks under the heading “Think and Answer.” Completing the assignments is designed to help students carefully read documents, analyze historical facts, and draw and justify their own conclusions.

At the end of each chapter, “Creative tasks” are formulated. Their implementation involves working with a complex of texts. The compilers of the anthology recommend that schoolchildren carry out such work under the guidance of a professional historian. The result of a creative assignment can be a historical essay, a speech at a scientific and practical conference, or the creation of an exhibition in a family or school museum.

Since the manual is intended primarily not for scientific work, but for educational work, the publication rules are simplified. There are no notes in the text, except for the omission of words inside or at the end of a sentence (the omission is indicated by an ellipsis). Some long texts are divided into several parts. Such parts, as well as entire texts, are sometimes preceded by headings in square brackets, invented by the compilers of the anthology. Also included in square brackets are words placed by the compilers in the text of the document for its better understanding. Asterisks indicate notes made by the author of the document. The notes by the compilers of the anthology are numbered.

Readers are invited to the fifth chapter of the anthology - “What was everyday life in the lives of generations” (the title has been changed in the newspaper publication).

Vladimir ZVEREV

Life and traditions of Siberia

A family of Siberian peasants.

Engraving by M. Hoffmann (Germany)

based on a sketch by O. Finsch, made in

Tomsk province in 1876

This chapter of the anthology is devoted to a description of the traditions characteristic of the culture and way of life of the Siberian peasantry in the 18th - early 20th centuries.

Traditions are those elements of culture or social relations that exist for a long time, change slowly and are passed on from generation to generation without a critical attitude towards them. For centuries, traditions played the role of the basis, the core of the everyday life of the people, therefore Russian society - at least until the “complete collectivization” at the turn of the 1920-1930s. - some historians call a society of the traditional type, and the mass culture of that time - traditional culture.

The meaning of peasant life was the labor produced by family members on “their” arable land (legally, the bulk of the land in Siberia belonged to the state and its head, the emperor, but peasant land use was relatively free until the beginning of the twentieth century). Agriculture was supplemented by livestock farming and crafts.

Knowledge of the environment, the “way” of family and community relationships, and the upbringing and education of children were also traditional. The entire material and spiritual culture of the village turned out to be traditional - the objective world created with one’s own hands (tools of labor, settlements and dwellings, clothing, etc.), beliefs preserved in the mind and “in the heart,” and assessment of natural and social phenomena.

Some folk traditions were brought to Siberia from European Russia during the settlement of this region, the other part had already developed here, under the influence of specific Siberian conditions.

The research literature reflects different approaches to assessing traditional folk culture, rural life in Russia and, in particular, Siberia. On the one hand, already in the pre-Soviet period a purely negative view of “patriarchalism, semi-savagery and real savagery” (Lenin’s words) appeared, and began to prevail in the works of Soviet historians, as if they reigned in the pre-revolutionary, pre-collective farm village and interfered with the authorities and intelligentsia in this village "cultivate" On the other hand, the desire to admire old folk traditions, even to their complete “revival,” has long existed and has recently intensified. These polar assessments seem to outline the space for the search for truth, which, as usual, lies somewhere in the middle.

For publication in the anthology, historical documents have been selected that describe and explain in different ways some aspects of the traditional culture of Siberians. Both the views of the peasants and the judgments of external observers - scientists (ethnographers, folklorists) and amateurs - a local doctor and teacher, a leisure traveler, etc. are interesting. Basically, the situation is presented through the eyes of Russian people, but there is also the opinion of a foreigner (an American journalist).

The questions of modern readers will be legitimate: how was the culture and life of our ancestors fundamentally different from today’s everyday life? Which of the folk ideas, customs and rituals remains viable in modern conditions, needs to be preserved or revived, and which are hopelessly outdated by the beginning of the twentieth century?

It is unlikely that the picture highlighted by the sources allows for unambiguous answers...

F.F. Devyatov

The annual cycle of working peasant life

Fedor Fedorovich Devyatov (c. 1837 - 1901) - a wealthy peasant from the village of Kuraginskoye, Minusinsk district, Yenisei province. In the second half of the 19th century. actively collaborated with scientific and educational institutions and press organs in Siberia.

[Take] the average family in terms of labor force. Such a family usually consists of a household worker, his [wife], an old father and an old mother, a teenage son from 12 to 16 years old, two young daughters and, finally, a small child. Such families are the most common. This family is busy with work all year round. No one here has time for extraneous earnings, and therefore, during harvesting, people often gather here, which takes place on a holiday.

Such a family, having 8 work horses, 2 plows, 5-6 harrows, can sow 12 acres. She uses 4 scythes for mowing and 5 sickles for reaping. With such a farm, it seems possible to keep up to 20 heads of cattle, horses, mares and teenage youngsters, 15 heads in total; sheep up to 20-30 heads and pigs 5. Geese, ducks, chickens are an integral part of such a farm. Although fishing exists, all the fish are spent at home and are not sold. An old father or grandfather usually does the fishing. If he sometimes sells part of the fish, it is only to gain a few coppers for God to buy candles.

6 dessiatines are sown with rye and egg, 3 dessiatines with oats, 2 dessiatines with wheat; and barley, buckwheat, millet, peas, hemp, all together 1 tithe. Potatoes and turnips are sown in special places. During the years of average harvest, the entire harvest from 3 dessiatines of rye, 2 dessiatines of oats, and 1 dessiatine of wheat is used for home consumption. All small bread also stays at home. Bread from 3 dessiatines of rye, 1 dessiatine of oats and 1 dessiatine of wheat goes on sale. All other products of the economy, such as cattle and lamb meat, pork, poultry, milk, butter, wool, feathers, etc. - all this goes for personal consumption in the form of food or clothing, etc.

Dealers of manufactured and small goods and, in general, all peasant needs are almost always also buyers of grain and other products of the peasant economy; in the shops, peasants take various goods according to the account and pay with farm products, bread, livestock, etc. In addition, due to the remoteness from cities, doctors and pharmacies, their own home self help. This is not like the treatment of healers, but simply every thrifty old housewife has five or six infusions, for example: infusion of pepper, trefoil, birch bud, cut grass ... and St. John's wort, and the more thrifty ones have camphor lotion, lead lotion, strong vodka , turpentine, mint drops, chilibuha, various herbs and roots. Many of these medicinal substances are also purchased from the store.

The peasants make carts, sleighs, bows, plows, harrows and all the necessary agricultural implements themselves. Many people also make a table, a bed, a simple sofa and chairs at home - with their own hands. Thus, the total expenditure in the said peasant family is up to 237 rubles per year. Cash income can be determined up to 140 rubles; the rest is therefore paid in products.

Not included in the income account, as well as in expenses: bread given for work in kind, for example, for sewing ... sheepskin coats, asyams from home cloth, shoes (many of these things are sewn at home by women, family members), for wool yarn , flax, soap factory for making soap, etc.; bread is also exchanged for lime for whitening walls. Mural dishes, wooden dishes, seeders, vessels, troughs, sieves, sieves, spindles, shanks are delivered by settlers from the Vyatka province and are also exchanged for bread. The exchange is made in this manner: the person who wants to buy a vessel fills it with rye, which he gives to the seller, and takes the vessel for himself; This is called the “scree price”.

This expresses almost the entire annual cycle of working peasant life. Its source is labor. The labor force arrives in the family, the development of the land arrives and increases; grain sowing and cattle breeding are increasing; in a word, income and expenses are growing.

Devyatov F.F. Economic life of the Siberian peasant /

Literary collection. St. Petersburg, 1885.

pp. 310-311, 313-315.

Notes

1 Help- collective neighborly mutual assistance. The church did not allow work on holidays, but the time of suffering was expensive, and the peasants circumvented the ban by working not on their farms, but on the farms.

2 Tithe- the main submetric measure of area in Russia, equal to 1.09 hectares.

3 Rye and egg- in this case - winter and spring rye.

4 Azam- men's outerwear, a type of caftan or sheepskin coat.

5 Mural dishes- covered with glaze.

6 Shank- a wooden tube, a part of equipment for spinning or weaving.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. What types of occupations were traditional in peasant farming?

2. What type (natural, market, mixed) can the described economy be classified as? Why?

3. What, according to F. Devyatov, is the main “source of peasant life”? What nature of the peasant economy does this author’s statement indicate?

4. Does your family have medical “home self-help”? What does it consist of?

N.L. Skalozubov

The peasants admired the plowing...

Nikolai Lukich Skalozubov is a Tobolsk provincial agronomist and a prominent public figure. As part of the Kurgan Exhibition in September 1895, he organized two plowman competitions. In total, 87 local peasants took part in them, who had to plow the paddocks allocated to them “quickly and well.”

First competition

The assessment [of the plowing results] was left to the peasants themselves, and the deputies approached their task with the utmost conscientiousness. If disagreements arose among them, the field was carefully examined by everyone again, and in most cases the verdicts were unanimous. The commission was also accompanied by some of the plowmen participating in the competition, listening carefully to the assessment.

The plowmen eagerly awaited the results of the assessment; the excitement of some was very great. One old man approached the manager and asked: “What is it, you know, my plowing didn’t turn up?” - “Yes, the old people say, you plow shallowly, you need to plow better!” Without saying a word, the old man falls down and lies unconscious for several minutes. They say that another plowman cried when he learned that his arable land was rejected.

Contrary to the existing opinion that the Siberian peasant is pursuing the productivity of arable implements to the detriment of the quality of work, it turned out to be completely the opposite: the appraisers recognized the best arable land where there were more furrows per paddock, and the remarkable thing is that this attribute was found out last, i.e. First, the arable land was assessed by the thoroughness of the development of the land, by its depth, and only then the furrows were counted.

Second competition

The best arable land, as last time, was considered to be the one that, at the greatest depth, seemed more leveled, with a large number of furrows in the paddock, small blocky, without virgin soil, with straight furrows and well covered with stubble. The best arable land, as expected, and according to the unanimous verdict of the peasants, turned out to be the arable land made with the Sacca plow. The peasants admired this plowing: not a single straw was visible on the arable land, the clods were crushed so finely and the layers covered each other so well that the field had the appearance of a fence. Nevertheless, half of the commission’s votes did not [immediately] agree to rate this arable land above excellent ploughing.

The appraisers did not even want to compare plow plowing with plowing plowing: “But this is a factory plow, put it wherever you want - it will plow well; We love our plow: it’s cheap, but you can plow it well.” “It’s good, but the road is not for us,” was the review [about the factory plow].

Skalozubov N.L. Report on [agricultural and handicraft industry]

exhibition [in Kurgan] and its catalogue. Tobolsk, 1902. S. 131-132, 134-135.

Notes

1 Plow Sacca- steel plow produced by the Rudolf Sack company (Kharkov).

2 Ploughing- in this case - made by a Siberian plow with two wooden coulters and moldboards.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. What criteria did the peasants present when assessing the quality of plowing?

2. What in the above description indicates the serious attitude of the peasants to the work of the plowman?

3. Why did the peasants prefer the plow rather than the plow in their daily work? How does this fact characterize their economic life and mentality (worldview)?

Eyewitnesses about family agricultural rituals

The first spring plowing in Western Siberia as described by F.K. Zobnina

Philip Kuzmich Zobnin is a native of Siberian peasants, a rural teacher, and the author of a number of ethnographic works.

Early in the morning, after breakfast or tea, they began to gather for the arable land. Every business must begin with prayer. This is also where plowing begins. When the horses are already harnessed, the whole family gathers in the upper room, closes the doors and lights candles in front of the icons. Before starting prayer, according to custom, everyone must sit down, and then get up and pray. After prayer, in good families, sons going to the arable land bow at the feet of their parents and ask for blessings. Before leaving the gate, they are often sent to see if there are any women on the street. It is considered a bad omen when a woman crosses the road on such an important trip. After such a disaster, at least come back...

That’s what they do if they haven’t left the yard yet: they go back to the upper room to wait and only then leave.

Zobnin F.K. From year to year (description of the cycle of peasant life

in the village Ust-Nitsinsky Tyumen district) //

Living antiquity. 1894. Issue. 1. P. 45.

The beginning of spring sowing in Eastern Siberia as described by M.F. Krivoshapkina

It's time to sow. We are planning to go to the field tomorrow. Preparations begin. First of all, they definitely go to the bathhouse and put on clean underwear; Yes, not only is it clean, more moral men even wear brand new, brand new underwear, because “sowing bread is not a simple matter, but everything is a prayer to God about it!” In the morning, a priest is invited and a prayer service is served. Then they spread a white tablecloth on the table and put a rug with a salt shaker that they have hidden since Easter; light candles in front of the image and pray to God; say goodbye to family; and if the father does not go himself, then he blesses the children who bow at his feet.

Upon arrival, horses are laid in the field; and the elder owner pours the grain into a sack (i.e., a basket made of birch bark or some twigs) and leaves it at the porch of the winter hut. Then, as usual, everyone sits down next to each other; get up; pray on all 4 sides; the eldest goes to scatter the grain, while the others plow. Having made this, as they say, beginning (beginning), everyone returns home, where dinner has already been prepared and all the relatives have gathered. All that remains, if it is close, is to send for a priest, who must bless both the bread and the wine and drink the first glass with the owner. Lunch is over. Younger family members or workers go to work hard; and the elder sees off the guests, pours grain into bags and goes out to sow.

Krivoshapkin M.F. Yenisei district and its life.

St. Petersburg, 1865. T. 1. P. 38.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. What do the peasants of Western and Eastern Siberia have in common in economic family rituals?

2. How do these rituals characterize the attitude of peasants to their work? Do the rituals described have a rational basis?

3. What conclusions about relationships in a peasant family can be drawn based on the proposed sources?

John Fraser

It will not be long before the Russian peasant becomes capable ofto a colonialist role

John Fraser is a famous American journalist who visited Siberia in 1901. He outlined his impressions in a book translated into various European languages.

Nowhere in the United States - after all, Siberia is often called the new America - is there such a huge expanse of beautiful land, as if created for arable farming and awaiting only human hands to cultivate it. However, there is little hope that Siberia, through the labor of its inhabitants alone, will allocate any of its natural resources to other countries. This situation will probably continue for several generations.

The Siberian peasant is a bad worker

It is an undoubted fact that the Russian peasant is one of the worst colonialists on the entire globe. A simple man strives mainly to eat enough and save a few kopecks for Sunday so that he can get drunk.

The Russian government is sincerely trying, as far as possible, to ease the fate of the immigrants. Thus, it orders American agricultural implements and sells them at a very low price. But wherever you look, you notice how little endurance the immigrant has. First of all, he, for example, does not want to live [on a farm] at a distance of 3, 5 or 10 miles from his neighbors, but strives to live in a village or city, even if the plot allocated to him is at a distance of 30 miles from them. Whether he cultivates a plot of land, sows wheat, but does not start harvesting on time and, thus, the crop is half destroyed. He reaps with a sickle, and meanwhile part of the wheat disappears from the rains. He has no idea about fertilizing the soil and doesn’t think at all about the future. He has no desire to get rich. His only desire is to work as little as possible. The principle that guides him in life is best described by the well-known word - “nothing.” This word means: “I don’t care, don’t pay attention to it!” In other words, it expresses the concepts contained in the words: phlegmaticity, indifference, negligence.

Of course, all the settlers are descendants of serfs; in the person of their ancestors, human dignity was subjected to the greatest humiliation. Therefore, one cannot hope to meet enterprising and independent people in their descendants; even in the expression of their faces there is a stamp of humiliation and indifference.

The government is trying with all its might to educate the settlers in such a spirit that they understand all the benefits of the latest improvements in agriculture and begin to apply them. But all his efforts do not lead to tangible results...

In all likelihood, it will not be long before the Russian peasant becomes capable of a colonialist role.

Poor life and low level of culture

The villages here have a very deplorable appearance. The huts are built from rough-hewn logs. The gaps between individual logs or boards are sealed with moss to protect against snow and wind. During the winter, the double windows are tightly closed and nailed, and in the summer they are not opened very often.

Russian peasants have no idea about hygiene. They do not know a completely separate bedroom. At night they spread skins and pillows on the floor and sleep on them without undressing. In the morning they just wet their face a little with water and don’t use soap at all.

It is clear that the entertainment of these people living far from cultural centers is very limited. Drunkenness is the most common occurrence here, and vodka is often of extremely poor quality. In every village there are guys who can play the accordion; Folk dances are often held to the sounds of it. Women are not very attractive: they have no intelligence, their eyes are expressionless. Their only dream is to acquire a red scarf with which they tie their heads.

The dwellings are characterized by terrible hygienic conditions and a stench, but this does not prevent their inhabitants from being extremely hospitable. While the peasant huts have a miserable appearance, in almost every village here you can find a large white church with golden or gilded domes. The men are simple-minded, very religious and superstitious. These are uncouth and dark people; his passions are the most primitive. A Siberian peasant will never do today what can be put off until tomorrow. But he was resettled in a rich country, and there is hope that soon culture will develop more here, and then Siberia will be able to shower the whole world with its riches.

Gleyner A. Siberia, America of the future.

Based on the essay “The Real Siberia” by John Foster Fraser.

Kyiv, 1906. pp. 15-17, 19-20.

Note

1 mile- English non-metric unit of length equal to approximately 1.6 km.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. How does the author’s assessment of peasant culture differ from the judgments contained in previous documents? Can it be considered absolutely indisputable?

2. What role does the author assign to the state in the “education of migrants”, and what does he see as the reasons for the failure of its activities?

3. Compare the description of the settlements and dwellings of Siberians made by an American journalist with the descriptions given in this anthology and in a textbook on the history of Siberia. What could be the reasons for such a striking discrepancy in estimates?

4. What future did John Fraser promise for Siberia? Was his prediction justified a hundred years later?

S.I. Turbin

Siberians are not keen on porridge...

When the coachman and I entered the hut, the owners were already sitting at the table and slurping cabbage soup; but let the reader not think that Siberian cabbage soup is the same as Russian cabbage soup. There is no similarity between them. Apart from water, meat, salt and thick grains, Siberian cabbage soup contains no impurities. Putting cabbage, onions and any greens in general is considered completely unnecessary.

The cabbage soup was followed by jelly, which was served with mustard, unfamiliar to our common people, diluted with kvass. Next came, not exactly boiled and not exactly fried, but rather a steamed pig, lightly salted and very fatty. The fourth dish was an open pie (stretch) with salted pike. Only the filling was eaten in the pie; It is not customary to eat the edges or the bottom. Finally, something like pancakes with cottage cheese, fried in cow butter, appeared.

There was no porridge. Siberians are not keen on it, and they don’t even like buckwheat. The bread is exclusively wheat, but very sour, and baked from batter. This was the daily lunch of a good peasant. Kvass, and even very good one, can be found in every well-built house in Siberia. Where bread is baked from rye flour, it is always sown on a sieve. Using a sieve is considered reprehensible.

- We, thank God, are not pigs! - say the Siberians.

- How can there be chaff, God forbid! - say the Siberians.

New settlers who have a strong addiction to it get a lot for sieve bread.

Turbin S.I. Old-timer. Country of exile and disappeared people:

Siberian essays. St. Petersburg, 1872. pp. 77-78.

Notes

1 Thick grain- large, not finely ground, peeled.

2 Chaff- chaff, ears of grain from which the grain has been winnowed. The sieve had smaller cells than the sieve, so the sifted flour turned out to be cleaner, without any admixture of bran and chaff.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. How did lunch in the house of a wealthy old-timer in Siberia differ from an ordinary Russian meal (highlight at least five features)?

2. How did sieve bread differ from bread sifted on a sieve? Why, according to the author, did the new settlers prefer sieve bread?

A.A. Savelyev

In the spring, when the river opens up, everyone rushes to wash themselves with fresh water...

Winter carts at the inn.

Engraving from a book published in Paris in 1768.

Records of signs, customs, beliefs and rituals were made by the ethnographer Anton Antonovich Savelyev (1874-1942) during the period of exile (1910-1917) in the Pinchug volost of the Yenisei district of the Yenisei province. In this publication they are grouped thematically.

In the field and in the arable land

The old owner says “venter” (ventel) “to go catch fish in the spring.” To get into the hut, you have to step over the fishing gear laid out on the floor. - “No, soaring, this is not necessary; no need at all. Don't step through. Through this, the fish will not go into it. It’s possible to spoil the venter.”

During the first spring fishing... the first more or less large fish caught is hit with a stick and at the same time they say, hitting the fish, “I got it, but it’s not the right one, send mother and father, grandmother and grandfather.”

It is advisable to steal something from someone on the day of sowing, at least, for example, a seryanka [match]. The harvest and sowing will be successful.

While planting potato [tubers], you cannot eat them, otherwise the mole will carry them away and spoil them.

About natural phenomena

How, how, soaring, this is true - a fire from a thunderstorm, this is certainly not “God’s mercy.” That’s what they say - “burn with God’s grace.” No, there is no way to extinguish such a fire with water. Then you can clear away [the ashes].

During hail and thunderstorms, they throw a shovel out into the street through a window (village of Yarki) or through a gate (village of Boguchany, village of Karabula), which they use to put bread in the oven... or an oven stick, so that both stop as soon as possible.

In the spring, when the river opens, everyone rushes to wash themselves with fresh water - in order to be healthy.

About pets

Peasant dwelling at night.

Engraving from a book published

in Paris in 1768

It happens that the dog loses its appetite. In the village of Pinchug, so that she can eat, they chop off the tip of her tail, and in the village. The Boguchans put a headband made of a bird cherry twig coated with tar, or simply a “tar rope” around her neck.

Cows are released shortly after Easter. The eldest member of the family goes out into the yard and there smears resin like a cross on the doors of the stables, flocks and gates, while saying a prayer. Along the gate through which the cows are let out, he spreads a belt on the ground, which he takes off himself. Having put down the belt and said the prayer again, he makes several half-bows. Then, standing in front of the gate, he will block (cross) it “three times.” Then the housewife [takes] a loaf of bread in her hands, goes out the gate and, breaking off piece by piece, beckons to the cow - “tprushi, tprushi, prayer, tprushi, Ivanovna, tprushi,” etc. She gives a piece of bread to a passing cow. So all the cows cross one after another, stepping over the belt, which is spread out so that they know their home, their gate. And the owner, following the leaving cows, whispers: “Christ is with you, Christ is with you!” - and baptizes one after another. This day is considered a semi-holiday and during it you are not supposed to swear.

When building a new house

When choosing a construction site, lots are cast. The housewife bakes 3 small “kolobushka” loaves of bread from rye flour. These latter are baked before the rest of the concoction. The next day, before sunrise, the owner takes these loaves of bread and puts them in his bosom, having previously girdled himself. Having arrived at the intended place, the owner ... reads a prayer; then he unties himself and monitors the number of loaves of bread that fall out of his bosom. If all three loaves fall out, the place is considered successful and happy for settlement; if two come up, it’s “this way and that”, and one is completely bad - you shouldn’t settle.

When they lift the “matitsa” onto the newly erected walls of a house under construction, they do this. On the “matitsa”, which lies at one end on the wall, they put a loaf of bread, a little salt and an icon; everything is tied to the mat with a new rukoternik [towel]. After raising the matitsa, the rest of the day is considered festive.

In the old days, when building a hut, a small amount of money was always placed under the lining [the lower crown of log walls], and a third of what was put under the lining was placed under the matnya [matitsa].

You cannot cut a window or door in a residential building - the owner will die or there will be a major loss.

Bread is the head of everything

Eh! Soaring, you are not the same, don’t bite off a piece of mine and don’t drink from my cup. You'll ruin it, go and soar. You will take all my power through your mouth. You'll make me weak.

The cut or broken side of the bread should be placed inside the table. In the same way, you definitely can’t put the kovriga or kalach with the “underneath” [bottom] crust facing up. In the first case, there will be little bread, and in the second, in the next world [the devils] will be held upside down.

When dividing the family [family division], the eldest cuts the loaf of rye bread into slices according to the number of men sharing or existing in the family. The person separating takes his part and moves away from the table. The women pour the kneading mixture and take away their parts.

In the old days, there was a custom not to destroy a whole loaf of bread in the evening. They said that “the carpet is sleeping.”

You can’t poke bread with a fork - in the next world [the devils] will lift it with a fork.

In family life

You cannot put the child down or sit him on the table - he will become capricious.

You can’t grab a child by the legs - it could be bad for him - he won’t be able to walk soon.

When the bride walks down the aisle, she must place a silver coin under her left heel, which means she will not need money when she gets married.

During an illness, you should not take off the shirt you were wearing when you fell ill, otherwise the illness will not go away soon.

For the deceased, a tow is placed in the coffin, and sometimes even pure flax fiber, so that it lies softer in the ground.

Religion and church holidays

The people of Russia are prayerful.

But we, the Cheldons, don’t know them [prayer]. There are seven people in our family, and Ivan is the only one who knows “Father” and “Virgin Mary”.

After Easter until Trinity, you cannot throw anything out of the window - Christ is standing there - “so as not to hurt him.”

On the evening before the holidays, you should not sweep the hut and throw away the rubbish from it. The owners will not have wealth.

You cannot stretch out on the bench with your feet towards the shrine - God will take away the power.

Every holiday necessarily begins the day before at sunset and ends with sunset. The eve of the holiday is called "suppers".

Folklore of the Angara region of the early 20th century // Living Antiquity:

Magazine about Russian folklore and traditional culture.

2000. No. 2. P. 45-46.

Notes

1 According to other sources, it was supposed to sow not with one’s own, but with someone else’s (donated or even “stolen”) seeds.

2 Half holiday- a day when only light work is allowed or work only until noon.

3 Matica- a log beam across the entire hut on which the ceiling is laid.

4 Tow- a combed bunch of flax, hemp, made for spinning.

5 "Our Father" and "Virgin Mother of God"- the most common prayers among peasants.

6 Goddess- a cabinet or shelf in the front corner of a clean room, where icons and other religious objects are placed, and the Gospel is placed.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. What features of the peasant mentality do the described beliefs and customs indicate?

2. What self-assessment of peasant religiosity does the source contain?

3. Why were the first pasture of cows and the raising of the “matitsa”, as well as the beginning of plowing and sowing, considered special days among the peasants?

4. What beliefs and customs have been preserved in Siberia to this day? What do your parents and grandparents know about them?

Siberian poet V.D. Fedorov

about your ancestors

Vasily Dmitrievich Fedorov (1918-1984) - Russian poet. Born in the Kemerovo region. He lived in Siberia for a long time.

Siberia, my land,

Eclipsed all the edges,

Oh, my golden penal servitude,

Shelter of the harsh forefathers

disenfranchised,

Where there were no lordly-royal whips,

But we don’t know washed bast shoes

With the iron of shackles gone

equally.

The people have not forgotten anything,

What in life of generations

It was everyday life.

The Siberian himself is a living given

Inspired both severity and hum annost.

In almost every Siberian family

For fugitives it was considered a matter of

honor

In the most visible and accessible place

Leave a glass of milk overnight.

And, touched by sinful lips,

They baptized with calloused fingers.

Vasily Fedorov. From the poem “The Marriage of Don Juan.”

THINK AND ANSWER

1. How to understand - from a historical point of view - the words: “There were no lordly-royal whips”; “The bare hands of unknown bast shoes and the iron of shackles passed on equal terms”?

2. Why does the poet call helping escaped convicts a “matter of honor” for a Siberian?

F.K. Zobnin

Before Easter, my brother and I don’t leave church...

Maundy Thursday - on the seventh, last,

week of Lent

Village Church

in Transbaikalia. Engraving from the book

G. Lansdell, published

in London in 1883

My brother and I were told the day before that we should get up earlier tomorrow: whoever gets up before the sun and puts on his shoes on Maundy Thursday will find many duck nests this year.

On Thursday morning, as soon as we get up, we see that on the shrine, near the icons, there is a loaf of bread and a large carved wooden salt shaker: this is quadruple bread and quadruple salt. This is a custom that has been established for centuries. After mass at the table, four quarters of bread with salt are eaten, but not all of it: part of it goes to livestock - horses, cows and sheep. From this bread God better preserves both livestock and people for a whole year.

Holy Saturday - last day

Lenten Eve on the eve of Easter

On the morning of this day, the eggs were painted and divided. We guys suffered as much as everyone else. But this is just the beginning. Soon your mother or father will add some from their share. After the division, everyone takes away their share until tomorrow, and tomorrow they can spend it as they please. We, complete and uncontrollable owners of our shares, of course, had no idea of using them the day before: we fasted for seven weeks and didn’t make it for several hours - that’s shameful.

Before Easter, my brother and I don’t leave church. It’s good in the church, and everything reminds us that the holidays are not far away: they clean the candlesticks, pour the bowls, insert new candles, transport the spruce tree and the puffer for the church - all this is done only for Easter. All this delights our young hearts, we rejoice and rejoice in everything.

Spring wood cutting

The woodcutter is the same suffering. If you don’t chop it down to plowing, you’ll be drowning the winter with cheesecake. Those who are older and stronger go to chop wood away from the settlement, to get started, i.e. nights for three - four, or even a week. The guys will chop some wood somewhere nearby: “it’ll still be useful for heating in the fall.” Chopping wood is fun. In the forest, even though there is no green grass or flowers, you can still eat: the birch tree [birch sap] has started running. You take a thuja tree, put it under a birch tree, and suddenly the day is full of thuja tree drippings. Of the small birch trees, the birch tree is not sweet, and not enough; it is necessary to pick birch trees from large birch trees. Mom didn’t let us drink a lot of birch: she says it’s “unhealthy.”

Sowing flax

Sowing flax is the most interesting for us. Feeding a family is a man's job, but clothing men is a woman's job. Therefore, when sowing flax, it became a custom to appease the peasants by placing boiled eggs in the flax seeds. That's why we love to sow flax. The father pours seeds into the basket, and egg after egg flies out with the seeds: “Boys, take them.” You can’t just take and eat an egg, you must first throw it up and say: “Grow flax higher than a standing forest.”

They also say that in order for flax to grow well, you need to sow it naked, but we have never tried this: it’s a shame, everyone talks, but if you take off your clothes, they’ll laugh at you.

Holy Trinity - Sunday in the seventh week

after Easter

Old Believers woman

from Altai on holiday

clothes.

Rice. N. Nagorskaya.

1926

On the evening of Trinity Day, young people of both sexes gather for clearing- this is the name of the festive gathering taking place on the banks of the Nitsa River. In the clearing, girls and boys, holding hands and forming several rows, walk one row after another, singing songs. It is called walk in a circle.

They're playing in the clearing on guard. The players are divided into pairs and become one pair after another. One or one of the players stands guard. The game consists of pairs running forward one by one, and the person standing guard while running tries to catch them. If he succeeds, then he and the caught player form a pair, and the remaining player stands guard.

One of the most necessary accessories of the clearing is wrestling. Usually wrestlers from the upper end [of the village] fight alternately with wrestlers from the lower end. Only two fight, while the rest, as curious people, surround the place of fight with a thick living ring.

The fight is always started by small fighters.

Each wrestler, entering the circle, must be tied over one shoulder and around himself with a girdle. The goal of the fight is to knock the opponent to the ground 3 times. Whoever manages to do this before the other is considered the winner. During the fight, lowering your hands from the girdle is strictly prohibited.

From the little ones the struggle gradually moves on to the big ones. In the end there remains the most skilled fighter, whom no one could defeat, and he, as they say, carries away the circle. To carry the circle means to win such a victory that serves as a source of pride not only for the wrestler himself, but also for the entire “end” or village to which he belongs.

Zobnin F.K. From year to year: (Description of the cycle

peasant life in the village Ust-Nitsinsky Tyumen district) //

Living antiquity. 1894. Issue. 1. pp. 40-54.

THINK AND ANSWER

A.A. Makarenko

Parties and masquerades continue with extraordinary excitement until Epiphany...

Alexey Alekseevich Makarenko (1860-1942) - ethnographer scientist. He collected materials about the life of Siberians in the Yenisei province (in particular, in the Pinchug volost of the Yenisei district) during the period of exile 1886-1899. and during scientific expeditions in 1904-1910. The book “The Siberian Folk Calendar in Ethnographic Relation” was published in its first edition in 1913. The fragments published here are dated according to the Julian calendar (old style).

|

|

|

|

Christmas masks of mummers of Siberians and Russian northerners,

|

||

1st [January].“New Goth” (year), aka “Vasiliev’s Day”.

On the eve of December 31st in the evening, Siberian village youth of both sexes... are busy with divination on their favorite topics - who will get married and where, who will get married, what kind of wife he will take, etc. In the Pinchug volost... fortune telling “on the New Goth” is accompanied by the singing of “podblyudnye” songs with the participation of girls and “bachelors” (guys), who gather for this in one of the suitable residential huts. In this case, the Pinchu residents support the custom of the inhabitants of the Great Russian provinces of European Russia.

More than ten people (girls and boys) do not sit at one table, so that there is one song for each person. The table is covered with a white tablecloth; each of the participants, taking a piece of bread, places it under the tablecloth in front of him; ten rings are placed on the served plate (you need to know your rings well or put “marks” on them). The plate is covered “tightly” with a scarf; then they sing a song; before the end of it, one of those not participating in the game... shakes the plate, takes out the first ring he comes across through a crack in the scarf: whose it turns out to be, he “bequeaths” it to himself (makes a wish). They sing to him (lingering motive):

This song is used to determine who is getting married. [According to other songs, it becomes clear whether you are going to find your betrothed in your own village or in someone else’s; whether he will be rich or poor, whether he will love; the girl will end up in a friendly or “disagreeing” family; will she soon become a widow, etc.]

Having finished the “sub-bowl” songs, they begin to perform divination. Here I will note the most characteristic forms of Siberian divination...

After putting a ring on the ring toe of the right foot, this bare foot is bathed in the “hole” (ice hole). A fortuneteller, for example, places one stick across an ice hole, and with the other she “closes” the ice hole; therefore, one stick means “lock”, the other “key”; this key is turned into the hole three times “against the sun” and taken home; the lock remains in place. The “zapetki” return from the ice hole, saying: “Betrothed, come to me to ask for the key to the ice hole, to water the horse, to ask for a ring!” Whichever good guy comes in a dream on cue, he will be the groom. Guys also bewitch their brides.

Girls alone go to the threshing floor or to the bathhouse, so that the “threshing floor” or “bathhouse” person strokes the naked part of the body that has been placed on purpose for this purpose: if he strokes it with a shaggy hand, it means a rich marriage, and vice versa.

Girls and boys, gathered in one circle, steal a “white mare” or horse for a while, take her to the “split” of roads, blindfold her with a bag; and when a girl or a guy sits on it, they circle it up to three times and set it free: whichever direction the horse goes, the girl will marry there, and the guy from there will take his wife.

On New Year’s Day, at dawn, “servants” (children) run around the huts alone or in groups and “sow” oats, as is done in Russia. The grains are thrown into the “front” or “red corner” (where the image is “God”), and they themselves sing:

Little “sowers”, who are seen as harbingers of the future “bread” harvest and new happiness for people, are given everything they can.

In the evening, persons of both sexes, from young to old, “mashkaruyuttsa”, i.e. They disguise themselves in whatever way they can, and visit the huts or “run to the farmhands” in order to amuse the owners. In the “farm” (hired) huts, “evenings” or “parties” are started with “games”, i.e. singing, dancing and various games.

But on Vasilyev’s Day (January 1) on the Angara, they try to end the “parties” before midnight (the first rooster) in order to avoid visits from the so-called shilikuns (evil spirits).

It happened once, according to Pinchu people’s belief... that at a party that lasted long after midnight, devils came running in the form of little people on horse legs, in “naked parkas” (Tungus clothing), with sharp heads, and broke up the party.

In the following days, normal work is carried out; but parties and masquerades continue with extraordinary animation until Epiphany. This custom is not local, Siberian, but also inherent in the peasants of European Russia.

Makarenko A.A. Siberian folk calendar.

Novosibirsk, 1993. pp. 36-37, 39-41.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. Why did young people in the old days attach such serious importance to various fortune-telling?

2. What role did song play in the life of peasant youth?

N.P. Protasov

After talking about this and that, I switched to song...

Having recognized all the singers of a given village, I usually asked the owner to invite them to me, as a lover of antiquity and songs, to talk. When the invitees arrived, I started a conversation with them about their household, land plots, family life, etc., then imperceptibly moved on to ancient rituals and song.

At first our conversation was monosyllabic and strained, and then gradually became livelier; when I explained that I myself was a Siberian peasant [by origin], we quickly became close and after an hour of such a frank conversation we became our own people. I was helped a lot by my knowledge of places, villages and people, which I acquired over many years, wandering around Siberia on foot and on horseback and covering up to forty-five thousand miles.

During the conversation, the hosts treated us to tea and snacks, and if there were girls there, then sweets - sweets and gingerbread, which I stocked up in Verkhneudinsk. After talking about this and that, I switched to song, and began to sing old songs myself and prove their charm, with which everyone present usually agreed, especially the old women.

If there were girls here, the old men began to reproach them for not memorizing old songs, but for singing some kind of “magpie tongue twisters.” Taking advantage of this, I tried to challenge them to competition, and the song flowed like a river, calmly, not forced, but pure, bright, performed from an excess of feelings. Having praised one of the songs, I asked him to repeat it in order to learn it myself. At the same time, my hand, holding a pencil, sketched the song on paper, and with subsequent repetitions the song was completely corrected.

On the phonograph I recorded as follows. When the singers gather, you will take a phonograph and place it in a visible place. The singers, seeing it, will become interested and begin to ask what kind of car it is. When you say that this machine listens to people and sings and speaks in human voices, then they begin to prove the impossibility of this. Then you invite them to sing a song, they readily agree, and the phonograph writes.

After each recording, I usually changed the diaphragm, the phonograph sang, the girls recognized each other’s voices, and often one of the singers said to her friend in surprise:

- Listen, Anyukha: Dunyashka is amazing!

After two or three hours, I already enjoyed special trust in this village, and then they sang whatever I wanted at my request. I gave silver rubles to all the singers, and to one old woman who sang six spiritual verses to me, I gave two gold rubles.

For this trip I recorded 145 melodies, of which 9 are spiritual verses, 8 are parables, 15 are wedding songs, 3 are songs of honor, 1 are ritual songs: Pomochan songs, 3 are Easter songs, 3 are Trinity songs, are 9 round dances, are 12 dance songs, comic - 2, voice - 60, recruit - 5, prisoner - 5, soldier - 10.

Protasov N.P.. How I recorded folk songs: Report on a trip to Transbaikalia /

News of the East Siberian Department of the Russian Geographical Society.

1903. T. 34. No. 2. P. 134-135.

Notes

1 Spiritual Poems- works of folk poetry and religious music performed at home.

2 Pricheti- lamentations of the bride at the wedding about her “maiden will”, as well as crying over the deceased during the funeral. Next: songs Pomochanskie- performances performed by participants; Trinity- sounded during the celebration of the Holy Trinity; provocal- lingering; recruiting- intended for seeing off new recruits to the army, etc.

THINK AND ANSWER

Historical traditions and legends of Siberians

About the “royal envoy” on the Chuna River

Recorded by I.A. Chekaninsky in 1914 in the village of Vydrina (Savvina), Nizhneudinsky district, Irkutsk province, from old-timer Nikolai Mikhailovich Smolin. The Smolins considered a certain Savva, a long-time immigrant from European Russia, to be their ancestor and the first Russian resident of Prichunye. When recording the legend, I. Chekaninsky sought to convey the features of the language of the “chunars”.

And it was almost two hundred years ago, or even two hundred years ago... In Chuna, there were only Assans and a little Yasashna (Tungus), and the Russians were afraid of her; no one went to Chuna. And the rassar [king] will send an envoy from the city of Tumen*. Here is a messenger swimming (and he was sailing from Udinsk**), near his tray with windows, and an assistant was sailing with him. They swam, and they swam to the [river] rapids.

The royal messenger says: “I,” he says, “are afraid to swim, because it’s dangerous, but I’d rather go along the shore!” He walked along the shore, and he himself was in armor and shackled with iron, and his assistant was sitting and swimming. Just then the royal messenger went along the shore, a little (Chud, Tungus) evo and let’s treat him to tamara*** from the lukof, fsevo and killed. Well, they took the beast from their arrows.

And the assistant of the Tsar’s messenger looks through the window and says: “You remember our sara, for the Tsar’s messenger you will have it!” Let's treat him and him with tamara and kill him****.

Apostle this and let us crush ourselves: with which the labas will cut down, put earth there, cut the pillars, the labas will fall and crush it. So they translated themselves a lot. Nowadays there are very few miracles, they used to come out to us [from the taiga], but now they come out less [less]. After that, the vice [threshold] became known as Tyumenets, as if he were a messenger from the city of Tumen.

And Savva swam after Etov, but oh well he swam, he didn’t even touch him at all. He also sailed from Udinsk to look for good places. He swam to this place (to Savvina), and settled here, built a hut, but this anbarushka remains from him. (M[ikandra] M[ichalich] pointed with his hand at the old, but not collapsed "anbarushka".) Then look (in) circle around the Russian villagers.

* City of Tyumen, Tobolsk province.

** City of Nizhneudinsk, Irkutsk province.

*** “Tamara” or “tamaruk” is the Tungus name for the arrow.

**** This legend is similar to numerous Siberian versions of the legend about the death of Ermak.

Chekaninsky I.A. Yenisei antiquities and historical songs:

Ethnographic materials and observations on the river. Chune. - M., 1915. - P. 86-88.

Notes from the compilers of the anthology

1 Assans and a little yasashna- the people of the Assan (now disappeared) and Evenki, related to the Kets, whom Smolin calls the yasak miracle, and Chekaninsky in his explanations - the Tungus.

2 Labas(storage) - an outbuilding on wooden pillars-piles.

About the discovery of the Baikal “sea”

The legend was recorded in 1926 by folklorist I.I. Veselov from N.D. Strekalovsky, a 78-year-old fisherman from the village of Bolshoye Goloustnoye, Olkhonsky district, Irkutsk region.

When the Russians went to war in Siberia, they had no idea about our sea. They made their way to Mongolia for gold and, in order to get a shorter route, they went straight. They walked and walked and came out to the sea. They were amazed and asked the Buryats:

- Where did the sea come from? What's your name?

But the Buryats in those days didn’t know how or what to say in Russian, and they didn’t have an “interpreter” for that. They wave at the sea and shout one thing:

- There was a gal. Was-gal.

This means he wants to say that there was a fire here, and after the fire everything fell through and became the sea. And the Russian again realized that this is what they call the sea, and let’s write it in the book: “Baikal.” So it remained [with this name].

Gurevich A.V., Eliasov L.E. Old folklore of the Baikal region.

Ulan-Ude, 1939. T. 1. P. 451.

Note

1 After the fire everything failed... The legends of the Buryats and Russians reflected the emergence of Lake Baikal as a result of a catastrophic fracture of the earth's crust.

THINK AND ANSWER

1. How deep is the historical memory of Siberian peasants?

2. What methods of formation of geographical names (toponyms) are recorded in folk memory?

3. How do folk legends explain the reasons for the disappearance of the Chud people?

4. What peoples can hide behind this name?

5. Do you know of other, more scientifically correct explanations for the name of Lake Baikal?

From the folk dictionary of Western Siberia

Folk metrology

|

|

|

Tools of labor of peasants of the Narym region: |

Harness- the time that a horse can go out in a plow without feeding and harnessing.

Gon, moving- part of a strip of arable land of 10-20 fathoms, which is passed by a plow at once, without turning it (Tobolsk district).

Del- 1) a measure of a [fishing] net of 1 arshin in width, 1 fathom in length; 2-3 weeks form pillar(Tyumen district); 2) part of the network that falls on the share of each shareholder in the sewing net.

Corral- 1) part of the field between two large furrows; 2) A small longitudinal plot of land approximately 75-125 square meters. fathoms (5 x 15-25 fathoms). This is not a completely defined measure; it is used to determine the approximate size of areas sown with flax, hemp, and turnips.

Flood- time until the stove is heated.

Istoplyo- the amount of firewood sufficient to light the stove once.

Kad- a measure of bulk solids, equal to four poods [see. below] or half a quarter.

Deck- a set of salary fees (capitation taxes, private volost duties and land survey fees) paid by peasants. In addition to salary taxes, they, as you know, also pay volost, secular or rural taxes and others. In the Tobolsk province, the size of the deck varies, depending on the area, between 4 1/2 and 5 rubles per head per year.

Kopna- a pile of hay of 5-7 pounds; in the north of the Tobolsk province it is used as a measure of meadow: plots are allocated per capita from which approximately an equal number of copens can be obtained.

Hand mop in the Tobolsk north is equal to 3-4 poods, women's when women do the cleaning - 3-3 1/2 pounds.

Peasant tithe- a measure of land of 2700 square meters. fathoms, less often 3200 square meters. fathoms or 2500 sq. fathoms, in contrast to the government tithe of 2400 square meters. fathoms.

Peasant fathom- hand-made fathom, as opposed to printed. There are two types of peasant fathom: 1) it is equal to the distance between the ends of two horizontally outstretched arms; 2) the distance from the top surface of the foot to the end of the fingers of an outstretched hand.

Nazhin- the number of sheaves that can be pressed from a certain measure of land.

Barn- 1) a bread dryer, in which a pit plays the role of an oven; in the latter they burn wood. With a two-row cage, the barn includes about 200 sheaves of spring and

180-190 sheaves of winter bread, with single row - about 150 sheaves; 2) a measure of grain bread in sheaves; a winter barn of 150-200 sheaves and a spring barn of 200-300 sheaves.

Plyoso- the visible space of a river between its two bends, which obscure its further flow from view. Pleso serves as a measure of length in the Tobolsk district. For example, if they are traveling along a river and do not know the number of miles left to travel, they often say that there are two reaches left to travel, three reaches, etc.

Pudovka- a measure for bread (usually wooden, less often iron), containing about 1 pood. Previously, grain bread was measured mainly with this pood; Now they are switching to a more accurate weight pud. That is why they distinguish - bulk pood(pudovka) and a hell of a lot, or weight.

Sieve- a measure of vegetable seedlings of 50-60 plants.

Sheaf- 1) a bunch of grain bread; a sheaf of hemp consists of four handfuls; 2) a measure of arable land in the northern part of the Tobolsk district; for example, they say: “We have land worth 300 sheaves.”

Stack- a measure of hay in the Tobolsk district is approximately 20 kopecks; for example, they say: “We mow 20 haystacks.”

Pillar- in addition to the usual meaning, it also means: a measure of the length of the canvas, equal to 2 arshins. Five pillars make up wall canvas.

Folk theology

Andili-arhandili(angels and archangels) - good spirits sent from God. One spiritual passage says about them:

God- 1) a supreme being, mostly invisible; 2) any icon, no matter who it depicts.

Sky- a solid stone vault above our heads. God and the Pleasant live in heaven. The sky sometimes opens or opens up for an instant, and at that moment people see a reddish light.

Rainbow- ends up drinking water from rivers and lakes and raising it to the sky for rain. Swimming when a rainbow appears is considered dangerous: it will drag you into the sky.

Last Judgment- it will be in Jerusalem, the navel (center) of the earth, all the nations of the earth will gather there, both living and long dead. “At the Last Judgment, Father True Christ orders that all sinners be covered with turf, so that neither a voice nor the gnashing of teeth can be heard.”

Cloud- the origin of thunder is attributed to Elijah the prophet. At every clap of thunder, it is customary to cross yourself and say: “Holy, holy, holy! Send, Lord, the quiet dew.” It is also believed that from time to time stone arrows fall from clouds to the ground, splitting trees. This action of the arrow is explained by the pursuit of the devil, who hides from it behind various objects.

Kingdom of heaven- eternal life after death, which is awarded to... those who, during earthly life, were diligent in visiting the temple of God, read or listened to the word of God, observed fasts, and honored father, mother, old men and women. In addition to a righteous life, the Kingdom of Heaven is awarded to the one who, at the time “the sky opens,” manages to say: “Remember me, Lord, in Your Kingdom.”

Naming and assessing human qualities

Wetness- a general term for three qualities: friendliness, courtesy and talkativeness. Vetlyanui the person is lively, talkative, and friendly.

Vyzhiga- a lost man, who has squandered everything and become capable of all sorts of dirty tricks. Expletive.

Gomoyun- a man who is diligent about housework and family. “Uncle Ivan keeps busy and tries, [see] how nicely he has set up his farm!”

Gorlopan(or loudmouth) - a loud, noisy person who tries to gain the upper hand in an argument by shouting. A contemptuous term.

Doshly- quick-witted, inventive, resourceful, intelligent (who can “get to everything”). “Our long-serving sexton is a jack-of-all-trades, lo and behold, he’ll rise to the rank of bishop!”

Durnichka- stupidity, savagery, ignorance, lack of education, bad manners, habits. “He looks good, [yes] with a fool in his head: suddenly, for no reason, no reason, he barks [curses].”

Serviceable- prosperous.

Self-interest- 1) benefit, profit, benefit; 2) thirst for profit, greed for money. “His self-interest has eaten up: everything is not enough for him, even if you sprinkle it with gold!”

Mighty(And can) - 1) powerful, hefty, strong, mighty (physically). “[Here’s a man like a man: wide with meat and bone, but God didn’t hurt him with his strength... Look for such capable men now"; 2) economically strong, serviceable, independent. “This powerful owner doesn’t care about taxes [i.e. easy to pay].”

Daily life- neatness, economic improvement. “She has golden hands: look at the way she lives in her hut!”

Everyday life- a diligent, clean housewife.

Exchange- an abusive epithet addressed to children, especially infants. Means: substituted (by the devil) child. It is based on the following belief, which is no longer accepted by many: the devil kidnaps children from some mothers who show good inclinations, and in return he palms them off with his own damn children.

Holy shit- dirty, unclean.

Ocheslivy- polite, knowledgeable and follows the rules of treating people well.

Posumimanny- obedient, submissive. “They have a nice guy: so quiet and submissive.”

Prosecutor's office- a person who makes you laugh wittily, cheerful, joker, quick-tongued. “Well, this Vaska is the procurator,” they laughed all dinner long because of him, “they just tore the bolognese [i.e. my stomach hurts].”

Uglan- a shy person; literally - hiding in a corner from strangers. Ironic term.

Luck- luck; lucky girls- dexterous and lucky. These words were probably brought to Siberia by exiles.

Firth- literally: a person standing in the form of a letter fert. In general, it means: what is important is a pompous, pretentious person (both internally and externally: by posture, speech, look). “The new clerk came out to the girls on the street and became a jerk. Feet and nuts, the sleigh is bent... Know, they say, that we are urban!”

Frya(does not bow) - a person who thinks too much about herself, is arrogant, touchy, turns up her nose. A contemptuous epithet applied to men and women. They also say “Frya Ivanovna”.

Sharomyzhnik- a slacker with vicious tendencies. A contemptuous term.

Patkanov S.K., Zobnin F.K. List of Tobolsk words and expressions,

recorded in Tobolsk, Tyumen, Kurgan and Surgut districts //

Living antiquity. 1899. Issue. 4.

pp. 487-515;

Molotilov A. The dialect of the Russian old-timers

Northern Baraba (Kainsky district, Tomsk province):

Materials for Siberian dialectology //

Proceedings of the Tomsk Society for the Study of Siberia.

Tomsk, 1912. T. 2. Issue. 1. pp. 128-215.

Notes

1 Standard fathom was approximately 2.1 m.

2 One arshin corresponded to approximately 0.7 m.

3 Bishop(correctly - bishop) - the highest Orthodox clergyman (bishop, archbishop, metropolitan).

THINK AND ANSWER

1. How does folk metrology differ from scientific metrology? What are the reasons for the appearance of the first and its existence in traditional society?

2. Determine the features of the worldview of Siberian peasants. What features of Christian and pagan consciousness were present in it?

3. What human qualities did the Siberian peasants value? What personality traits were perceived by them as negative? Why?

Let's smile together

So much for “conversation”!

Do you know what was called “Siberian conversation” in Russia? The habit of Siberians is to crack pine nuts for hours in complete silence when they come to visit or gather for a gathering in the evening.

Siberian joke

In the fall, gold miners leave the gold mines. Many have a lot of money. By the time they get home, they are greeted everywhere like dear guests, treated to food, drunk, and robbed in every possible way. And they even hunt them like wild animals.

And such a prospector, still a young guy, stopped for the night in one village. The owners - an old man and an old woman - greeted him like family: they fed him, gave him something to drink and put him to bed. In the morning the prospector went out to smoke and breathe fresh air. He looks - the old owner is sitting on the porch and sharpening a large knife.

- Who are you, grandpa, sharpening such a knife for? - the guy asked him.

- I'm pointing at you, my dear. At you. I'll direct him properly and kill him.

Then the guy sees that things are bad for him. The yard is large, the dam is high and dense, the gates are firmly locked. House on the outskirts. Start screaming and you won't get through to anyone.

Meanwhile, the old man sharpened a knife - and on the guy. And that one, of course, is from him. From the porch to the yard. The old man is behind him. The guy is from him. The old man is behind him. An old woman watches from the porch as an old man chases a guy across the yard. We made one circle. Second. On the fourth lap, the old man collapsed in complete exhaustion.

The old woman sees this and begins to scold the guy. And he is like this, and like this:

- They accepted you like family! They gave you something to drink, feed you and put you to bed. Instead of gratitude, what are you doing? You son of a bitch! Look what you brought the old man to...

Rostovtsev I. At the end of the world: Notes of an eyewitness. M., 1985. S. 426-427.

Publisher:

Publishing House "First of September"

Transcript

1 Federal State Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Altai State Academy of Culture and Arts" Faculty of Artistic Creativity Department of Social and Cultural Activities HOLIDAYS AND RITES OF THE PEOPLES OF SIBERIA Curriculum for full-time and part-time students in the specialty "Socio-cultural activities" qualification "Cultural director" -leisure programs" Barnaul 2011

2 Approved at a meeting of the department of socio-cultural activities, protocol 6 Recommended for publication by the council of the faculty of artistic creativity, protocol 7 Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia: curriculum for full-time and part-time students in the specialty “Socio-cultural activities” and qualification “Cultural director” -leisure programs” / comp.a.d. Plyusnin; AltGAKI, published by the Department of Social and Cultural Activities. Barnaul, p. The curriculum for the discipline “Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia” is a document that defines the main content of training in this discipline, the range of knowledge, skills and abilities to be acquired by students. The curriculum of the academic discipline “Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia” formulates the goals and objectives of the course being studied in accordance with its place and significance in the general system of disciplines in the specialty “Socio-cultural activity”, establishes the structure of the academic subject, the content of sections and topics. Compiled by: Associate Professor A.D. Plyusnin 2

3 CONTENTS 1. Explanatory note.4 2. Thematic plan of the course “Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia” (full-time course Contents of the course Supervised independent work Extracurricular independent work of students Questions for tests and exams Thematic plan of the course “Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia” (correspondence form of training Course content Test topics Recommended reading..23 3

4 EXPLANATORY NOTE The curriculum for the discipline “Holidays and rituals of the peoples of Siberia” is included in the SD.R block and is associated with the study of the festive culture of ethnic groups living in the territory of northern, southern and eastern Siberia. Studying the course as one of the most important in the training of specialists in the specialty “Socio-cultural activities”, qualification “Director of cultural and leisure programs” has cultural, pedagogical and artistic significance. The course material gives a correct understanding of the origin of holiday culture, reveals its originality, and emphasizes the continuity in the formation and development of holidays and rituals of various ethnic groups. The purpose of the course is to familiarize students with the festive and ritual culture of the peoples of Siberia, to instill practical skills in the effective use of course materials when conducting festive and ritual programs. Objectives of the course: - equip with knowledge in the field of festive and ritual culture of ethnic groups of Siberia; - to form the attitude of students towards the use in practical activities of the richest festive and ritual heritage of Siberia - to include students in the cultural process of creating, organizing and conducting festive and ritual programs based on national and ethnic specifics. As a result of studying the course, students should know: - the origins, role, significance of the festive and ritual culture of ethnic groups; - structure of ethnic groups; - content (structure) of holidays and rituals, means of expression and forms of expressiveness of holidays; 4