Kyiv. Shchekavitsa, Ar-Rakhma and Intercession Monastery

Shchekavitsa. What is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear this word? Legendary founders of Kyiv. And also Prince Oleg the soothsayer, who was allegedly buried on Mount Shchekavitsa. Legends covered in the ashes of time. If you look at this hill from Podil today, you will see only modern rich fortress cottages, a radio tower, a military unit and a recently built mosque. This, it seems, is all of Shchekavitsa. All, but not all. The history of the place is not limited to what we see now, as people who are accustomed to measuring everything and everyone with money and property are trying to convince us of this. History is evidence of the events that took place here, the aura of the place is something far from the material benefits of our time. This cannot be privatized, it can only be sold as a tourist attraction, but it is very expensive and cannot immediately “recoup” the funds spent. Therefore, it is more profitable to simply build up “nobody’s” territory, not to mention any local legends there.But Shchekavitsa is not just a legend, although there is plenty of legend here. Shchekavitsa (Skavika), or Olegova Mountain (maximum height - 172.2 meters above the level of the Dnieper), has a history that goes far beyond the chronological limits of the city of Kyiv. Between this mountain and neighboring Jurkovitsa (possibly the legendary Khorevitsa), a large number of archaeological sites and settlements have been discovered, ranging from the Paleolithic to early Slavic treasures of Roman coins. The vast majority of these finds are associated with the construction of a brick and beer factory near Shchekavitsa, and not with systematic archaeological excavations. The famous archaeologist Mikhail Braichevsky wrote: “Unfortunately, the time of the initial settlement of Shchekavitsa remains unknown - special archaeological research has never been carried out on this mountain, and ancient things from random finds date back to the 7th century. AD." He assumed here the existence of a settlement from the time of the Zarubintsy culture, that is, the turn of the new era.

The next stage in the historical life of the area is the most famous and legendary. In the Tale of Bygone Years, Shchekavitsa is mentioned as the mountain on which Shchek, one of the three brothers who founded Kyiv, “sat.” According to the overwhelming majority of modern historians, both Shchek and Khoriv, in contrast to the real Kiy, are toponymic characters of the legend that appeared to impart sacredness to the foundation of the city. Compare, for example, other legendary triplets: Rurik, Sineus, Truvor (founders of the Rurik dynasty) Rus, Czech, Lyakh (founders of the Polish state) Rosh, Meshekh, Tubal (biblical ancestors of the East Slavic peoples).

There are several hypotheses explaining this name. Some historians derive explanations from the Slavic word “cheek” - steep-sided, steep river bank. Others - from the word “tickle”, “cheek” - nightingale. Still others interpret it through a variant of the name Skavika from the Greek “skafos” - ravine, abyss. But if the name of the brothers’ sister, Lybed (as well as the name of the Dnieper tributary) is associated with the presence of Hungarian tribes in these territories and their legendary country of Lebed, then probably the name Shchek should be looked for not in the Slavic or Greek languages, but in the languages of the peoples who rolled across the Dnieper region at the beginning of the first millennium of the new era.

The hypothesis that Danprtstadir, the capital of the Gothic state of Germanaric (IV century), was located on Szczekavitsa has been criticized by modern historians, but has never been completely refuted by anyone due to the lack of an archaeological map of the mountain. It is also unclear whether someone was “sitting” on the mountain. That is, whether an early Slavic castle was located there, like the “town of Kiya” in the area of the Tithe Church, is unclear, but already during the period of Kievan Rus, that is, 300-400 years later, it was one of the populated suburbs of the capital of the great power.

The first Kiev Rurikovich, the prophetic Prince Oleg, was buried on Shchekavitsa in 912. This is what tradition and the Tale of Bygone Years tell us. In the thousand years that have passed since that event, who among the travelers has not been shown by the people of Kiev “that very mound on Shchekavitsa”, who has not looked for the famous grave on that mountain. Pushkin, Maksimovich, Lokhvitsky, Zakrevsky. The pedantic local historian Lavrentiy Pokhilevich even found two “graves” of Oleg, to which excursions were conducted until the 50s of the 19th century. Olegovskaya Street, passing by the mountain, was formed on the site of the path that led to the “grave” of tourists.

Whether Oleg’s “graves” were razed during other burials on Shchekavitsa already in the 19th century, whether a mound existed over the grave all this time, or whether the Varangian leader was buried there is not known for sure, but archaeological excavations in 1995 in a very small area on the mountain confirmed the existence of a cemetery here dating back to the 10th-13th centuries. In 1121, the Church of St. John was built in the Shchekavitsa area; in 1183, the priest of this church, “Father Vasily,” was elected abbot of the Pechersk Monastery. And during excavations in 1980, the remains of a stone foundation were found, probably of this particular temple at the current address of the street. Olegovskaya, 41.

In 1146, information about Shchekavitsa appears in connection with the betrayal here, on the mountain, of the Kyiv regiments of Grand Duke Igor Olegovich in favor of the grandson of Monomakh Izyaslav Mstislavich (reigned in 1146-1154). In 1150, Prince Georgy Vladimirovich of Suzdal (better known as Yuri Dolgoruky) entered Kyiv through Dorozhich (modern Dorogozhichi) and Oleg's grave (Shchekavitsa), abandoned by Prince Izyaslav. The following year, Izyaslav recaptured Kyiv, marching with his regiments again through Shchekavitsa. And in 1161, the regiments of Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich of Chernigov, an ally of the Grand Duke of Kyiv Rostislav-Mikhail Mstislavich, were located here.

So, the mountain was populated enough to accommodate the allied detachments, and besides, Shchekavitsa covered the approaches to Kiev from the Dorozhichi side, so it is quite possible that it had some kind of fortification, as the Laurentian Chronicle says about it - “teremets”. In 1169, the troops of Mstislav Andreevich, the son of Andrei of Suzdal Bogolyubsky, with his allies, passing through Shchekavitsa, besieged Kiev, and after three days of siege, for the first time in history, they took the capital by storm and shamefully robbed it, after which Kyiv lost its primacy among the “Russian cities.”

The population of Shchekavitsa was interrupted after the Mongol invasion. We don’t know what happened at the very top, but under the mountain, during the construction of a brewery in 1873, a crypt with 400 skeletons from the time of the devastation of Kiev by Mengli-Girey (mid-13th century) was found, and in the 20th century, nearby, a burial place with more than a thousand skulls In the 14th century, Shchekavitsa belonged to the Kyiv Castle built on a nearby mountain. From a military point of view, a fortified position had to be created here, since the mountain is the key to Podil, and its capture guaranteed access to this part of the city, where its economic life was concentrated, especially in the Lithuanian period. In 1543 and 1548, during the Revision of the Kyiv Castle, wheat and, in some places, grapes were grown on the mountain.

In 1581, the Kiev governor, Prince Konstantin Ostrozhsky, transferred the lands of Shchekavitsa to the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In 1604, these lands were transferred to the Catholic Bishop of Kyiv - Biskup. At the foot of Shchekavitsa (where the bus station is now) there was even a Biskupsky courtyard, and the mountain was called Biskupsky. In 1619, King Sigismund III, with his charter, transferred these lands to the Podolian townspeople for resettlement from the districts of Podol flooded by the Dnieper.

During the Ruins in 1658, the brother of Hetman Ivan Vygovsky, Daniil, approached Kyiv with his regiments, took a position on Shchekavitsa and gave battle to the Russian troops of the boyar Sheremetyev. The Cossack-Tatar troops lost the battle with heavy losses. However, the fortifications of the mountain were never taken. But the turbulent events of the Ruins caused irreparable harm to Shchekavitsa. Only populated by Podolyans, it was again devastated, depopulated, abandoned, only brick factories and wineries for processing grapes began to be built under the mountain. The mountain became a place for walks and performances. Here, on Shchekavitsa, in 1705, students of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy acted out the famous tragicomedy “Vladimir” by rector Feofan Prokopovich.

In 1770, a “pestilence infection” was brought to Kyiv from Moldova and Poland. Then, in four months, up to 8 thousand citizens died in the city. It became clear that the old tradition of burying the dead in the area around churches needed to be changed. Therefore, in 1772, the territory of Shchekavitsa was chosen as a cemetery for the Podolyans. Over the 150 years of its existence, this cemetery has become the last refuge for many famous Kiev residents: the Balabukh, Gorshkevich, Maksimovich, Lakerd, Grigorovich families.

The writer and poet Konstantin Dumitrashko are buried here; Kyiv researcher, outstanding historian Vladimir Ikonnikov; architect Andrey Melensky; outstanding composer Artemy Vedel; historian, archaeologist, church leader Pyotr Lebedintsev; linguist Konstantin Mikhalchuk; writer Ivan Nekrashevich; humorist writer, ethnographer Pyotr Raevsky; writer, minister of the UPR government Pyotr Stebnitsky; literary critic, linguist Mikhail Tulov. Since the cemetery was designed for all Podolians, it was multi-confessional. Some of the burial places of Muslims and Old Believers have been preserved.

In 1782-1786, the Church of All Saints was erected at the cemetery using donations from townspeople. Perhaps this was the last creation of Ivan Grigorovich-Barsky. The three-part, single-dome structure was designed in the spirit of “Elizabethan Rococo.” The shape of the font repeated the font of St. Andrew's Church. In 1809, after a lightning strike, the temple was repaired. At the same time, a pseudo-Gothic bell tower was built over the porch. In 1857, using funds raised by subscription, a warm chapel was built to the north in the name of St. Mary Magdalene, the entire church has been renovated, the iconostasis has been gilded. In the narthex of the church there was kept an interesting portrait of Savva Tuptalo (possibly from his lifetime), as well as a bone from the skeleton of a certain fossil animal.

In the 1870s, a copper image of the Archangel Michael, which once adorned the town hall, was transferred to the church for storage (then transferred to the city museum, now in the collection of the Museum of the History of Kyiv). In 1914, at the expense of the church warden Grigory Bulava, a new “marbled” iconostasis was built instead of the old one, damaged by fungus. In 1935, the Presidium of the City Council decided to close the church; the city improvement construction office was tasked with dismantling the temple within a month, which was done. The brick clergy house on the street has still been preserved. Shchekavitskaya, 32-b. Even after the official closure of the cemetery, burials continued in the Old Believer part. Many of the tombstones date from 1943-1945, and there is even a military burial. The last burial dates back to 1951.

In 1947-1988, during the technological confrontation and the Cold War, the mountain became inaccessible to Kiev residents. A walk there could lead to meeting the “investigative authorities.” On the site of the Church of All Saints and the oldest part of the cemetery, a radio tower 136 meters high and another 180 meters above sea level was built in 1951. This was one of many “jammers” that played an important role during the “war for the minds of the Soviet people.” These towers operated until 1988. Since 1993 - as a radio center and tower for mobile operators.

In the 70s, the basin between Shchekavitsa and Tatarka with Yurkovitsa was built up with standard nine-story buildings, but the approaches to the “object” remained empty. Now times have changed, and the attack on Shchekavitsa began again. In 1998, the Muslim community received permission from Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma to build a mosque near a small cemetery of fellow believers. Finishing work on the mosque is still ongoing. On the slope of Shchekavitsa there is also a Baptist chapel and a Seventh-day Adventist center. Their buildings are fundamental, executed by skilled architects and masterfully integrated into the slopes of the mountain. But this is just a façade. Several new “houses” are already hiding among the ravines and thickets on Shchekavitsa.

Opposite the mosque, large-scale construction of cottages is in full swing. Apparently, it has only just begun to unfold. And 100 meters from the foundation of the 12th-century church, the construction of a multi-storey building continues, for the construction of which part of the observation mound was dug up by excavators. On the other side, the mound has already been half demolished. This is the same quarry that the authorities were forced to stop digging “for now.” At the same time, thirty meters behind the hill, but on the other side, construction continues. In general, Shchekavitsa invites you to get acquainted with its mysteries, as well as protect it from modern barbarians.

In the 1950s, the flat part of Kyiv Podil looked abandoned and provincial. Mostly one- and two-story wooden houses are shabby, abandoned and unkempt. And some of these houses were even propped up with dark logs to prevent them from collapsing. The most dilapidated of these houses were located at the foot of the mountains: Shchekavitsy, Yurkovitsy and in the area - Tatarka. From the memories of the post-war period, I remember courtyards with locked gates. In the courtyards there are dilapidated buildings, woodsheds, dovecotes... Here they hung out laundry and shook out rugs, and children played wonderful and varied yard games. There were few cars on the cobblestone streets. There were many carts drawn by horses. Janitors collected horse manure with scoops. Podol did not at all resemble the aristocratic center of the city. Everywhere there are burdocks, nettles, chickens, dogs, wooden benches, under which there are mountains of seed husks... But in the spring - the intoxicating smell of lilacs!

My post-war childhood passed at the foot of Shchekavitsa - an ancient Kyiv hill with forgotten cemeteries, ravines, crooked paths and streams flowing down... Time seemed to have stopped here...

I remember with what pleasure we, the boys from Podol, climbed to the top of this mountain and flew paper kites. They were not afraid to climb into the clay caves dug into the mountain. The Tatar cemetery with crescents on the graves looked unusual. And the old city cemetery, with its beautiful stone gates, was not so destroyed then.

The people on the mountain lived poorly... Mostly working people: shoemakers, bakers, artisans... People of different nationalities also lived peacefully: Ukrainians, Russians, Tatars, Gypsies, Jews, Armenians... We boys were equally friends with children of any nationality. We divided people according to other criteria - greedy or kind, coward or brave, you can rely on him in difficult times or not... The proximity of the Zhitny Market had an effect. Market swindlers, thieves, and moonshiners lived on the mountain...

Easter

Today the holiday of Easter is celebrated solemnly and openly. You could say it's more "official". These are services in churches, lighting of paskhas, exchange of colored eggs, visits to cemeteries, etc. These are, perhaps, all the signs of the current celebration, in contrast to the times of “militant atheism.” But what is surprising is that at all times the great Christian holiday has been loved by the people for the miracles that occur during this spring season.

People living at the foot of Shchekavitsa and on Tatarka, even in post-war Soviet times, had icons in almost every house. These icons were passed down from generation to generation. I remember that shortly before Easter people were whispering that in such and such a house the icon began to bleed myrrh, that is, it began to release oily, fragrant moisture in drops. This was considered a blessing from above to this house for the good deeds of the owners. So it was customary that people carried their myrrh-streaming icons to church so that as many people as possible would pray on them. They say that in the year of Stalin's death in Kiev Podol, bells rang spontaneously in churches. But in the office of the school director on Tsymlyansky Lane in 1953, before Easter, a portrait of Stalin fell from the wall. The director was so scared that he didn’t immediately understand where to run - either to bow to the church or to hand in his party card to the district committee.

Holy springs

Once upon a time, there were a lot of natural springs on Shchekavitsa, Yurkovitsa and other hills stretching along Frunze Street to Kurenevka. However, indiscriminate construction, uncleared windbreaks, concrete blocks, logs and various debris “buried” these holy Kyiv springs. Today, perhaps in the area of Mylny Lane, at the foot of Mount Yurkovitsa, the historical Jordan Spring has been restored. Why Jordanian? It has long been said that in ancient times one Kiev merchant, making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, dropped his personal ladle into the Jordan River. Returning to Kyiv, he went to Yurkovitsa to drink water from the spring and miraculously caught the ladle that had been lost in the Jordan. Since then, the source has been called Jordan. And although this source was destroyed many times and covered with earth, today, thanks to the work of Christian ascetics of the restored St. Nicholas-Jordan Church, this holy source exists.

The springs of the Kyiv mountains are ancient deep waters that are many thousands of years old. This water has a healing effect on humans. I was lucky to talk with Mother Anna, who lived at the foot of Shchekavitsa in the last century. She said: ancient people prayed over this water, so it is still healing and carries prayer information. This is a kind of message to us from our ancestors, and an indication of the path of life. No wonder Jesus preached his best sermons by the waters of Lake Gennesaret. After all, water, like the human soul, is eternal. It rises upward in the form of water vapor, then falls to Earth from the clouds in the form of rain, is absorbed into the soil and after a certain time rises to the surface again through water sources.

Near Mother Anna’s house, at 17 Tsimlyansky Lane, lived a certain Anatoly Fogel. A spring came out of the ground in his yard. Today everything here is broken, covered with concrete slabs and walled up. And the spring, especially in spring, bursts out of the ground, washing away these concrete slabs...

To conclude the Podolsk topic, I will show you another corner of old Kyiv, not spoiled by the attention of tourists, somewhere between Podol and the outskirts of the Upper Town, where he took me in November 2012 pan_sapunov . A dilapidated old area on the slopes of Mount Shchekavitsa, views from it of Podol and northern industrial zones, as well as the only and perhaps the first Ar-Rahma mosque in the ancient Russian capital and the largest cathedral of the Intercession Princess Monastery in Kiev.

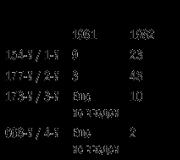

For starters, a map that might be worth making earlier. Here you can clearly see the structure of Podol as a trapezoid between the Dnieper and the harbor, and the wide streets of Upper and Lower Val crossing it (formally, two different streets with a boulevard), and the wooded slope of the Kiev mountains separating the Upper City from the Dnieper valley. We examined points 1 and 2, 3 and 4 - , 5 and a lot of little things - , 6-7 - , and those highlighted in red are ahead of us.

2.

There are two main ascents to Shchekavitsa from the Nizhny Val through the Biskupschina district (i.e. “Episcopal region”) - one along Lukyanovskaya Street past the hefty Seventh Day Adventist Church:

3.

The other one along Olegovskaya Street - in perspective the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross (1811-41), on the left is Castle Hill:

4.

Lined with wooden houses, Olegovskaya is perhaps at once the most non-metropolitan and non-Ukrainian street in Kyiv. More like another ancient Russian capital - Vladimir, where the same streets descend from its ancient cathedrals to Klyazma.

5.

6.

Although the building at the very top is clearly stylized as Ukrainian Baroque. I'm not even sure that this is Stalinist architecture - similar architecture was practiced here in the early 1920s.

7.

From the southern slope of Shchekavitsa you can clearly see the City of the Dead and the Landscape Alley passing above it:

8.

Although the quarter did not take place, and was built in an unsuitable place for living, it is beautiful, damn it! It will be even more beautiful when it is completely empty and dilapidated:

9.

In one of the courtyards at the top there was a collection of cars from the mid-20th century. Such a strange corner of stopped time, completely impossible in Moscow.

10.

This courtyard opens to the northern slope of Shchekavitsa, towards the gigantic Podolsko-Kurenyovskaya industrial zone, separating the elite Obolon from the city. Behind the ravine is another mountain Jurkovitsa:

11.

View up. A little to the left, behind the branches are Ar-Rahma and the Intercession Cathedral, captured in the introductory frame. Below is a linen weaving factory, perhaps even pre-revolutionary. In the distance, the TV tower goes into the clouds (385m, only Ostankino is higher in the former USSR):

12.

Almost on the same line with it, but in front of the high-rise buildings you can see the wooden Makaryevskaya Church (1897) - with all the abundance of wooden churches in Ukraine, it is a huge rarity for Kiev (as well as for Moscow):

13.

Well, the path to the Shchekavitsa observation deck lies through the garages. That’s why it’s already little known - it’s really not easy to find the way to it, at least I certainly wouldn’t have found it alone. The garages resemble the dwellings of some Berbers or Nubians.

14.

Here is the top - a narrow cape jutting into the very middle of Podol. The triangulation point is topped with a cross, because the cross is a landmark:

15.

The views from this site in both directions are completely different. On the right is Stary Podol, its rectangular layout is clearly visible. Old and new houses merge from afar like a patchwork of colors:

16.

The Florovsky Monastery is hidden almost entirely by the second spur of Shchekavitsa, except for the bell tower spire. But Poshtovaya Square with the Nativity Church (1809-14, on the right) and the Brodsky Mill (1906, on the left) is clearly visible. On the horizon is the Metro Bridge (1965) - about 5 kilometers away:

17.

A little to the left is the Pritisko-Nikolskaya Church (1750), with the loss of the Bratsky Monastery the largest and most noticeable in Podol. Behind it is the Greek Church (1915) on Kontraktova Square:

18.

To the left you can see the round building (1947-53) of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy and the thick chimney of TsES-1 (1909-10), but the main thing here is just the roofs of the old Podol:

19.

Even further to the left is the Annunciation House Church (1740) of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy. The golden spire behind the houses is the Church of St. Nicholas on the Water (2004), and behind it (and therefore beyond the water of the Dnieper) Trukhanov Island with a parachute tower sticking out of the fallen forest. Finally, just on the horizon, on the left bank, is the Resurrection Greek Catholic Cathedral. The Uniates (previously expelled from Kyiv in the 1630s) chose the place for it masterfully - it is visible from the entire Upper Town from Dorogozhychi to Vydubychi, from most bridges, and invariably attracts attention with its “Orthodox high-tech”. What else is needed for messiahship?

20.

Ordinary Podol - roofs and square blocks. It is interesting that most of its churches are not visible from Shchekavitsa - neither Dukhovskaya at Mogilyanka, nor the ancient Ilyinskaya, nor the one being built on Pochaininskaya:

21.

Far, far beyond Troyeshchina there is a pipe from the largest thermal power plant in Kyiv (1962), the second tallest building in the city (270m) after the TV tower (however, in Ukraine there are many pipes higher than 300 meters):

21a.

If you look directly from the mountain, there is no longer any special antiquity here; individual old houses are sometimes found among high-rise buildings and factories. On the left, for example, are the Kievmlyn elevators (this does not mean “Kyiv, Mlyn!”, but “Kiev Mill”):

22.

Obolonskaya Street with a 119-meter pylon of the northernmost Moscow Bridge in the city (1976) in the future - 3.5 kilometers to it, and behind it is the multi-storey and huge Troyeshchina, where, as any Kievite knows, there is no metro:

23.

Cranes of the Leninskaya Kuznitsa shipyard (founded in 1865 as the Fyodor Donat plant) behind the harbor:

24.

The harbor itself with a “warehouse” of sand and rubble on the other side, against the backdrop of the “candles” of Obolon:

25.

But the dominant feature of this part of Podol is CHPP-2 of the early Soviet era:

26.

And on the left, right under the mountain, there is a very picturesque couple of a Soviet brick factory (closer) and a pre-revolutionary brewery (further away) with the oldest (1895) factory chimney in Kyiv. She also owns an elevator, to the right of which are the workshops of a ceramic factory, again clearly from the 19th century:

27.

However, let's be honest, Kyiv itself is not industrial - neither now, nor a hundred years ago. If in St. Petersburg it takes several days to inspect old industrial zones, and in Moscow there are comparable numbers of individual plants and factories, then here the enterprises are small and there is almost nothing heavy like metallurgy or carriage building. But at the same time, Kyiv was “raised” by hundreds of sugar factories scattered throughout the Little Russian provinces.

28.

However, although the factories here are small and not spectacular, there are really a lot of them:

29.

This is what it is, an industrial zone in Kiev style:

30.

Even further to the left is Jurkovica. St. Cyril's Church (1139, appearance in the 1740s), famous for its frescoes, peeks out from over the edge of the mountain. Under the mountain, the St. Nicholas-Jordanian Temple (2000) on the site of its predecessor, demolished in 1935:

31.

Well, even further to the left are the same views as from the yard in front of the garages. The view from Shchekavitsa is about 270 degrees, and we have exhausted it. So let's go towards the Upper Town - almost on Shchekavitsa itself, on Lukyanovskaya Street, there is the Ar-Rahma Mosque - the first in the history of Kyiv:

32.

Before the revolution, every provincial city in Russia was equipped with a church, a church, a mosque and a synagogue, but in Kyiv - where there clearly could not but be an omnipresent Tatar community - the construction of a mosque came only in 1913 and, for obvious reasons, was not completed. Perhaps the very thought of a Muslim temple in a city of Orthodox shrines was abhorrent to the authorities and people. But there is no escape from globalization, and thanks to its location on the Ar-Rahma hill, it is much more noticeable in the landscape of Kyiv than any of the Moscow mosques is in the landscape of Moscow. The main building of the mosque was built in 1998-2004 in the “Ottoman” style characteristic of mosques in Ukraine:

33.

The rest of the complex is literally brand new:

34.

The area is somehow very calm and peaceful. By the way, next to the mosque is an Old Believer cemetery.

35.

As for the Intercession Monastery, I’ll honestly say that we went to it on a different walk and from a different direction. Of course, you can also walk from the mosque, but you will have to zigzag and walk up and down. And the entrance to the monastery is from the Upper Town, in the courtyards of the Kudryavets district, known since the 1840s:

36.

37.

The Pokrovsky Princess Monastery was founded by Alexandra Petrovna (nee Oldenburg), daughter-in-law of Nicholas I, that is, the wife of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. In 1881, the latter accused her of infidelity and connections with no less than her confessor, Archpriest Vasily (Lebedev), despite the fact that he himself cohabited and had children from another woman. Out of such disgrace, the princess left for Kyiv and, as in Ancient Rus', set about creating a monastery in order to go there. In fact, the project was very good: she founded a monastery-hospital, the nuns and novices of which were also junior medical staff. The monastery was built in 1889-1911, and its free hospital even had such technological wonders as the first X-ray room in Kyiv. In 1889, Nikolai Nikolaevich died, and Alexandra Petrovna took monasticism under the name Anastasia, and died in 1900... such a story with a dirty beginning and a bright end.

Closed in 1925, the Intercession Monastery reopened during the Nazi occupation and never closed again - not an isolated incident in Kyiv. During the war it again served as a hospital for both armies.

The entrance to the monastery is through this “pear” of the Holy Gate:

38.

There we have such a scene, which should please a lot of people here:

39.

There are two churches in the monastery. Church of the Intercession - the temple of the hospital itself:

40.

St. Nicholas Cathedral is the largest in Kyiv, height 65 meters, width comparable to:

41.

Candles on a city that looks like a Kiev cake... Still, the sugar industry somehow metaphysically influenced the “sweet” Kyiv architecture:

42.

43.

A jeep is blessed at the entrance, and firewood is placed in the backyard. Not everything is so clear...

44.

Well, to end the post, in addition to the cathedral and mosque, there is also an absolutely amazing “house with menorahs”. What do they mean here?

45.

Still a wonderful city!

Is it difficult to get to unusual places where you have been living and walking for five years?

It turns out not. You just have to deviate from the usual autumn route to Podol via Baggovutovskaya and Nizhneyurkovskaya a little to the side - past the Makarievsky Church, go to the right, along the steps

on Lukyanovskaya street.

There, the gilded domes of the Holy Intercession Convent are shot through the nine-story panel buildings.

The gates of the Old Believer (or Shchekavitsky) cemetery are slightly open.

Last Sunday we wandered along the paths, paths, thickets, getting to know the place, but knowing nothing about its history...

They simply recorded some moments, were surprised, asked themselves questions and often did not find answers.

Now I will try to find them (Google will help me :).

What we saw, we examined.

All the graves in this necropolis are no later than the mid-forties. There is a lot of time for the liberation of Kyiv.

And the earliest of those preserved and seen date back to the beginning of the 19th century.

Although, there was one late burial from 2016. The mother (probably still the mother), who found peace here back in the 20s, took in her 99-year-old daughter, born in 1917. During this time, a series of people, authorities, and eras passed. And here is the cheerful, not at all old lady, face in the color photograph on the tombstone next to the serious, black and white one of the mother. Close people who have missed each other by almost a century...

Graves with photographs are, however, rare here. The cemetery is very neglected, dead and unconscious. The tombstones, apparently, were collected from destroyed ones, placed on someone else’s or their own, but crumpled, broken foundations.

At the same time, there are well-kept graves from the beginning of the last century.

This grave looked like one of the most visited. What was striking was that despite the fact that we didn’t meet anyone at the cemetery itself, someone had recently lit lamps here. And left a handful of coins.

Here lay a certain Ivan Rastorguev, called Bosym... Maybe some kind of holy fool? We built versions and, as it turned out later, they were not mistaken.

I was particularly puzzled by the group of crosses with towels and visors.

And something similar to a church lectern opposite them.

Even further, but on the same outlying site, there is another tombstone

with an unusual epitaph for a person “who did not want to live in the world and enjoy life...”

Did he commit suicide? And could a suicide be buried here, within the cemetery. The answer to this question was not found.

The paths from the cemetery lead to the Shchekavitsa pagorby.

And there - all of Kyiv in the palm of your hand.

(Now I’ve learned that it’s also worth finding the Shchekavitsky “270-degree platform” located behind the narrow passage between the garages of houses 42 and 44 Olegovskaya Street. From here, in good weather, a huge part of the capital is visible: from the Wind Mountains to Podol and the Left Bank.)

The place, no matter how you look at it, is historical.

"...Mount Shchekavitsa was mentioned already in 1151 in connection with the attempt of Prince Yuri Dolgoruky to capture Kyiv...

The name “Shchekavitsa” is traditionally associated with the fact that Shchek “sat” (that is, settled) on it - according to the chronicle, one of the founders of the city, brother of Kiya.

In the Tale of Bygone Years there is a mention that in 912 the Kiev prince Oleg was buried on Shchekavitsa. According to legend, the Legend formed the basis of the work of A.S. Pushkin's "Song of the Prophetic Oleg". Hence another name for the mountain – Olegovka.

Sometimes the name Skavika is found, which is probably a simplified version of “Shchekavitsa”.

Here's what we found out about the history of the cemetery.

The cemetery on Shchekavitsa appeared after the epidemic of 1770, when 6 thousand people died - out of 20 thousand Kiev residents. Before this, people were buried near churches or even near homes: during floods, burials created additional problems for the residents of Podol. Founded in 1772, the Shchekavitskoe cemetery was surrounded by an earthen rampart, burial rules were established, and in 1782 the Church of All Saints was built in the Baroque style. The city grew. In 1900, the city government decided to close the cemetery, although in some cases people were buried here until 1928. And according to the general plan of Kyiv in 1935, the upper terraces of the Kyiv hills, including those on Shchekavitsa, should have been turned into recreation and entertainment parks. The church and most of the cemetery, except for the Old Believer and Muslim sections, were then demolished. And instead of a park, Kiev residents received a military radio tower, walks near which could end in interrogation by the KGB.

From here:

The head of the historical and cultural society “Staraya Polyana” Alla Kovalchuk said that they began to deal with the issue of preserving the Shchekavitsky cemetery in the early 1990s. Together with the Soldiers' Mothers Foundation and the historical and patriotic club “Poisk”, we held cleanup days and achieved the installation of a concrete fence. War mass graves were found and a memorial plaque was installed. The memorial “Monument of Sorrow” has already been made; it is now in the studio of the architect Vera Yudina. But there is a delay due to lack of funding. (Since the information is from 2007, funding apparently was never found).

Below the Old Believer cemetery there is another one, Tatar. Burials there continued until the mid-70s. Neat fences, next to the inscriptions in Russian there is Arabic script.

And behind the fence of this double necropolis is the largest mosque in Kyiv.

Further, if you walk along Olegovskaya Street (formerly Pogrebalnaya) towards the Zhitny Market, you can see ancient wooden houses with carved platbands

which are adjacent to the elite townhouses "Shaslyviy Maetok" -

Immediately behind Podol, bending around it from the southern side, there are three mountains elongated in one line: the southern one, closest to the chronicle “Mountain” (later it was called Andreevskaya or Starokievskaya) - Castle Mountain (Kiselevka, Frolovskaya Mountain);

further, to the northwest - Shchekavitsa, and behind it, farthest from the Dnieper, - Yurkovitsa (Jordan Heights).

There is no doubt that it was called that way already in the era of Monomakh, that’s what it was called in the 18th century, and that’s what it’s called today.

The origin of the toponym Shchekavitsa is associated with the name of one of the founders of Kyiv - Shcheka. Near the foot of the mountain there are Slavic burials of the pre-Christian period of 8-9 centuries.

On the mountain itself, as legends say, the Prophetic Oleg was buried: “And they buried him on the mountain called Shchekavitsa. His grave still exists today. That grave is called Oleg’s” (The Tale of Bygone Years, 912). A street leads to the mountain, which is now called Olegovskaya.

In 1619, the historical area above Podol, Mount Shchekavitsa, was transferred to the townspeople for settlement.

There is probably no place in Kyiv more mysterious and not fully explored than Mount Shchekavitsa, located above the flat part of Podol.

People also call it Olegovka or Bald Mountain (by the way, there are five Bald Mountains in total in Kyiv).

Vladimir Ivanovich Dal claimed that witches from all over the Russian Empire gathered here to hold Sabbaths and collect magical herbs.

Another mystery of the mountain is the supposed grave of the Prophetic Oleg, glorified by Pushkin. It is believed that it was here that the Kiev prince Oleg was buried in 912, who allegedly died from the bite of a snake that crawled out of the skull of his war horse. They say that A.S. Pushkin himself walked along the mountain for a long time, looking for the prince’s grave. Some historians and scientists, having studied the topography of old Kyiv, agreed that Oleg’s grave is located in the place where the old observatory is located.

Mount Shchekavitsa is also mentioned in the chronicle of 1151 in connection with the attempt of Prince Yuri Dolgoruky to capture Kyiv. Already in the 12th century, as evidenced by a chronicle article from 1182, there was a stone church on the mountain, and during the election of the abbot of the Pechersk Monastery, ambassadors were sent here for priest Vasily. It is known that the Kiev Castle was built here in the 15th century.

At the end of the 19th century, Mount Shchekavitsa became a city cemetery, on which the Church of All Saints was built in 1782. The composer A. Wedel, the first city architect A. Melensky, and the architect V. Ikonnikov are buried here. At first it was a city cemetery for residents of Podol, whose lives were claimed by the cholera epidemic of 1771-72. Then members of the magistrate, rich townspeople, and famous townspeople began to be buried here. For a long time, there have also been cemeteries of Muslims and Old Believers on the mountain.

Currently, a mosque, Protestant and Orthodox churches coexist peacefully on Shchekavitsa. By the way, the master plan for the reconstruction of Kyiv in 1935 envisaged the construction of an amusement park on this mournful site!