Antique statues of women. Ancient Greece sculpture from the classical period

The first, archaic period of Ancient Greece is the VIII - VI centuries. BC. The sculpture of this period represented still imperfect forms: snubnoses - marble statues of young men with wide-open eyes, lowered hands, clenched into fists, also called archaic Apollos; kora - figures of graceful girls in long clothes and with beautiful curls on their heads. Only a few dozen such static sculptures by nameless authors have reached us.

The second, classical period in development is the V - IV centuries. BC. The sculptures and their Roman copies of the innovative sculptors of this time have been preserved. Pythagoras of Regia overcame staticity; his figures are characterized by emancipation and fixation of two movements - the initial one and the one in which they will find themselves in a moment. His works were vital and truthful, and this delighted his contemporaries. His famous sculpture “Boy Taking out a Splinter” (Palazzo in Rome) amazes with its realism and beauty of plasticity. We can judge about another great sculptor Myron only from a very damaged Roman copy of the bronze “Discobolus”. But Polykleitos went down in the history of the art of sculpture as a great innovator. He studied the human body for a long time and carefully, and in a toga, with mathematical precision, he calculated the proportions of its ideal, harmonic form and wrote a large treatise on his research called “The Canon.” According to the “Canon”, the length of a person’s foot should be a sixth of the height of the leg, the height of the head should be an eighth of the height, etc. As a sculptor, Polykleitos devoted his work to the problem of depicting movement in a moment of rest. The sculptures of a spearman (Doriphorus) and a youth with a victory ribbon (Diadumen) demonstrate the balance of energy created by chaism, another discovery of Polykleitos. Chaism – in Greek means “cruciform arrangement”. In sculpture, this is a standing human figure with the weight of the body transferred to one leg, where the raised hip corresponds to the lowered shoulder, and the lowered hip corresponds to the raised shoulder.

The ancient Greek sculptor Phidias became famous during his lifetime for creating a 13-meter statue of Zeus sitting on a cedar throne, and known as one of the seven wonders of the world. The main material used by Phidias was ivory; the body of the god was made from it, the cloak and shoes were made from pure gold, and the eyes were made from precious gems. This unsurpassed masterpiece of Phidias was destroyed in the fifth century AD by Catholic vandals. Phidias was one of the first to master the art of bronze casting, as well as the chryso-elephantine technique. He cast thirteen figures from bronze for the temple of Apollo of Delphi, and made the twenty-meter-tall Virgin Athena in the Parthenon from ivory and gold (chryso-elephantic sculpting technique). The third, Hellenistic period, covered the 4th-1st centuries. BC. In the monarchical system of the Hellenistic states, a new worldview arose, and after it a new trend in sculpture - portrait and allegorical statues.

Pergamon, Rhodes, Alexandria and Antioch became centers of sculptural art. The most famous is the Pergamon school of sculpture, which is characterized by pathos and emphasized dramatic images. For example, the monumental frieze of the Pergamon Altar depicts the battle of the gods with the sons of the Earth (giants). The figures of the dying giants are full of despair and suffering, while the figures of the Olympians, on the contrary, express calmness and inspiration. The famous statue of the Nike of Samothrace was erected by the sea on a cliff on the island of Samothrace as a symbol of the victory of the Rhodes fleet in the battle of 306 BC. The classical traditions of sculptural creativity are embodied in the statue of Agesander “Aphrodite de Milo”. He managed to avoid affectation and sensuality in the depiction of the goddess of love and show high moral strength in the image.

The island of Rhodes was glorified by the sculpture “Laocoon”, the authors of which were Agesander, Athenadorus and Polydorus. The sculptural group in their work depicts a pathetic scene from one of the myths of the cycle. The 32-meter gilded bronze statue of the god Helios, which once stood at the entrance to the harbor of Rhodes and was called the “Colossus of Rhodes,” is also called one of the seven wonders of the world. Twelve years were spent creating this miracle by Lysippos' student Chares. Lysippos, by the way, is one of the sculptors of that era who very accurately knew how to capture a moment in human action. His works have reached us and become known: “Apoximen” (a young man removing dirt from his body after a competition) and a sculptural portrait (bust). In “Apoximenos” the author showed physical harmony and inner refinement, and in his portrait of Alexander the Great - greatness and courage.

Ancient Greek sculpture is the leading standard in world sculptural art, which continues to inspire modern sculptors to create artistic masterpieces. Frequent themes of sculptures and stucco compositions of ancient Greek sculptors were the battles of great heroes, mythology and legends, rulers and ancient Greek gods.

Greek sculpture received particular development in the period from 800 to 300 BC. e. This area of sculptural creativity drew early inspiration from Egyptian and Middle Eastern monumental art and evolved over the centuries into a uniquely Greek vision of the form and dynamics of the human body.

Greek painters and sculptors achieved the pinnacle of artistic excellence that captured the elusive features of a person and showcased them in a way that no one else had ever been able to show. Greek sculptors were particularly interested in proportion, balance, and the idealized perfection of the human body, and their stone and bronze figures became some of the most recognizable works of art ever produced by any civilization.

The Origin of Sculpture in Ancient Greece

From the 8th century BC, archaic Greece saw an increase in the production of small solid figures made of clay, ivory and bronze. Of course, wood was also a widely used material, but its susceptibility to erosion prevented wooden products from being mass-produced as they did not exhibit the necessary durability. Bronze figures, human heads, mythical monsters, and in particular griffins, were used as decoration and handles for bronze vessels, cauldrons and bowls.

In style, Greek human figures have expressive geometric lines, which can often be found on pottery of the time. The bodies of warriors and gods are depicted with elongated limbs and a triangular torso. Also, ancient Greek creations are often decorated with animal figures. Many of them have been found throughout Greece at sites of refuge such as Olympia and Delphi, indicating their general function as amulets and objects of worship.

Photo:

The oldest Greek limestone stone sculptures date back to the mid-7th century BC and were found at Thera. During this period, bronze figures appeared more and more often. From the point of view of the author's plan, the subjects of the sculptural compositions became more and more complex and ambitious and could already depict warriors, scenes from battles, athletes, chariots and even musicians with instruments of that period.

Marble sculpture appears at the beginning of the 6th century BC. The first life-size monumental marble statues served as monuments dedicated to heroes and nobles, or were located in sanctuaries where symbolic worship of the gods was carried out.

The earliest large stone figures found in Greece depicted young men dressed in women's clothing, accompanied by a cow. The sculptures were static and crude, as in Egyptian monumental statues, the arms were placed straight at the sides, the legs were almost together, and the eyes looked straight ahead without any special facial expression. These rather static figures slowly evolved through the detailing of the image. Talented craftsmen emphasized the smallest details of the image, such as hair and muscles, thanks to which the figures began to come to life.

A characteristic posture for Greek statues was a position in which the arms are slightly bent, which gives them tension in the muscles and veins, and one leg (usually the right) is slightly moved forward, giving a sense of dynamic movement of the statue. This is how the first realistic images of the human body in dynamics appeared.

Photo:

Painting and staining of ancient Greek sculpture

By the early 19th century, systematic excavations of ancient Greek sites had revealed many sculptures with traces of multicolored surfaces, some of which were still visible. Despite this, influential art historians such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann objected so strongly to the idea of painted Greek sculpture that proponents of painted statues were labeled eccentrics and their views were largely suppressed for over a century.

Only the published scientific papers of the German archaeologist Windzenik Brinkmann in the late 20th and early 21st centuries described the discovery of a number of famous ancient Greek sculptures. Using high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, specially designed cameras, plaster casts and some powdered minerals, Brinkmann proved that the entire Parthenon, including the main part, as well as the statues, were painted in different colors. He then chemically and physically analyzed the original paint's pigments to determine its composition.

Brinkmann created several multi-colored replicas of Greek statues that were toured around the world. The collection included copies of many works of Greek and Roman sculpture, demonstrating that the practice of painting sculpture was the norm and not the exception in Greek and Roman art.

The museums in which the exhibits were exhibited noted the great success of the exhibition among visitors, which is due to some discrepancy between the usual snow-white Greek athletes and the brightly colored statues that they actually were. Exhibition venues include the Glyptothek Museum in Munich, the Vatican Museum and the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The collection made its American debut at Harvard University in the fall of 2007.

Photo:

Stages of the formation of Greek sculpture

The development of sculptural art in Greece went through several significant stages. Each of them was reflected in the sculpture with its own characteristic features, noticeable even to non-professionals.

Geometric stage

It is believed that the earliest incarnation of Greek sculpture was in the form of wooden cult statues, first described by Pausanias. No evidence of this survives, and descriptions of them are vague, despite the fact that they were likely objects of veneration for hundreds of years.

The first real evidence of Greek sculpture was found on the island of Euboea and dates back to 920 BC. It was a statue of a Lefkandi centaur by an unknown terracotta sculpture. The statue was collected in parts, having been deliberately broken and buried in two separate graves. The centaur has a distinct mark (wound) on his knee. This allowed researchers to suggest that the statue may depict Chiron wounded by the arrow of Hercules. If this is indeed true, this may be considered the earliest known description of the myth in the history of Greek sculpture.

The sculptures of the Geometric period (approximately 900 to 700 BC) were small figurines made of terracotta, bronze and ivory. Typical sculptural works of this era are represented by many examples of equestrian statues. However, the subject repertoire is not limited to men and horses, as some found examples of statues and stucco from the period depict images of deer, birds, beetles, hares, griffins and lions.

There are no inscriptions on early period geometric sculpture until the early 7th century BC statue of Mantiklos "Apollo" found at Thebes. The sculpture represents a figure of a standing man with an inscription at his feet. This inscription is a kind of instruction to help each other and return good for good.

Archaic period

Inspired by the monumental stone sculpture of Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Greeks began carving in stone again. The individual figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of oriental models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture. Examples of sculptures from this period are the statues of Lady Auxerre and the torso of Hera (early archaic period - 660-580 BC, exhibited in the Louvre, Paris).

Photo:

Such figures had one characteristic feature in their facial expression - an archaic smile. This expression, which has no specific relevance to the person or situation depicted, may have been the artist's tool to give the figures an animated, "live" quality.

During this period, sculpture was dominated by three types of figures: a standing naked youth, a standing girl dressed in traditional Greek attire, and a seated woman. They emphasize and summarize the main features of the human figure and show an increasingly accurate understanding and knowledge of human anatomy.

Ancient Greek statues of naked youths, in particular the famous Apollo, were often presented in enormous sizes, which was supposed to show power and masculine strength. These statues show much more detail of the musculature and skeletal structure than the early geometric works. The clothed girls have a wide range of facial expressions and poses, as in the sculptures of the Athenian Acropolis. Their drapery is carved and painted with the delicacy and care characteristic of the details of sculpture of this period.

The Greeks decided very early on that the human figure was the most important subject of artistic endeavor. It is enough to remember that their gods have a human appearance, which means that there was no difference between the sacred and the secular in art - the human body was both secular and sacred at the same time. A male nude without character reference could just as easily become Apollo or Hercules, or depict a mighty Olympian.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce sculpture just for artistic display. Statues were created to order, either by aristocrats and nobles, or by the state, and were used for public memorials, to decorate temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is often proven by ancient inscriptions on statues). The Greeks also used sculptures as grave markers. Statues in the Archaic period were not intended to represent specific people. These were images of ideal beauty, piety, honor or sacrifice. This is why sculptors have always created sculptures of young people, ranging from adolescence to early adulthood, even when they were placed on the graves of (presumably) older citizens.

Classical period

The Classical period brought a revolution in Greek sculpture, sometimes associated by historians with radical changes in socio-political life - the introduction of democracy and the end of the aristocratic era. The Classical period brought with it changes in the style and function of sculpture, as well as a dramatic increase in the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting realistic human forms.

Photo:

The poses also became more natural and dynamic, especially at the beginning of the period. It was during this time that Greek statues increasingly began to depict real people, rather than vague interpretations of myths or completely fictional characters. Although the style in which they were presented had not yet developed into a realistic portrait form. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, created in Athens, symbolize the overthrow of aristocratic tyranny and, according to historians, become the first public monuments to show the figures of real people.

The classical period also saw the flourishing of stucco art and the use of sculptures as decoration for buildings. Characteristic temples of the classical era, such as the Parthenon at Athens and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, used relief molding for decorative friezes and wall and ceiling decoration. The complex aesthetic and technical challenges faced by sculptors of that period contributed to the creation of sculptural innovations. Most of the works of that period have survived only in the form of individual fragments, for example, the stucco decoration of the Parthenon is today partly in the British Museum.

Funeral sculpture made a huge leap during this period, from the rigid and impersonal statues of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical era. These monuments are usually found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict “ideal” types of people (a yearning mother, an obedient son), they increasingly become the personification of real people and, as a rule, show that the deceased leaves this world with dignity, leaving his family. This is a noticeable increase in the level of emotions relative to the archaic and geometric eras.

Another noticeable change is the flourishing of the creativity of talented sculptors, whose names have gone down in history. All information known about sculptures in the Archaic and Geometric periods focuses on the works themselves, and rarely is attention given to their authors.

Hellenistic period

The transition from the classical to the Hellenistic (or Greek) period occurred in the 4th century BC. Greek art became increasingly diverse under the influence of the cultures of the peoples involved in the Greek orbit and the conquests of Alexander the Great (336-332 BC). According to some art historians, this led to a decrease in the quality and originality of the sculpture, although people of the time may not have shared this opinion.

It is known that many sculptures previously considered the geniuses of the classical era were actually created during the Hellenistic period. The technical ability and talent of Hellenistic sculptors is evident in such major works as the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Pergamon Altar. New centers of Greek culture, especially in sculpture, developed in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamon and other cities. By the 2nd century BC, the growing power of Rome had also absorbed much of the Greek tradition.

Photo:

During this period, sculpture again experienced a shift towards naturalism. The heroes for creating sculptures now became ordinary people - men, women with children, animals and domestic scenes. Many of the creations from this period were commissioned by wealthy families to decorate their homes and gardens. Lifelike figures of men and women of all ages were created, and sculptors no longer felt obligated to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.

At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities that arose in Egypt, Syria and Anatolia needed statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This led to sculpture, like ceramics, becoming an industry, with subsequent standardization and some decline in quality. That is why many more Hellenistic creations have survived to this day than the era of the classical period.

Along with the natural shift towards naturalism, there was also a shift in the expression and emotional embodiment of the sculptures. The heroes of the statues began to express more energy, courage and strength. A simple way to appreciate this shift in expression is to compare the most famous works created during the Hellenistic period with the sculptures of the classical phase. One of the most famous masterpieces of the classical period is the sculpture “The Carrier of Delphi”, expressing humility and submission. At the same time, the sculptures of the Hellenistic period reflect strength and energy, which is especially clearly expressed in the work “Jockey of Artemisia”.

The most famous Hellenistic sculptures in the world are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (1st century BC) and the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos, better known as the Venus de Milo (mid-2nd century BC). These statues depict classical subjects and themes, but their execution is much more sensual and emotional than the austere spirit of the classical period and its technical skills allowed.

Photo:

Hellenistic sculpture also underwent an increase in scale, culminating in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), which historians believe was comparable in size to the Statue of Liberty. A series of earthquakes and robberies destroyed this heritage of Ancient Greece, like many other major works of this period, the existence of which is described in the literary works of contemporaries.

After the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek culture spread to India, as shown by the excavations of Ai-Khanum in eastern Afghanistan. Greco-Buddhist art represented an intermediate stage between Greek art and the visual expression of Buddhism. Discoveries made since the late 19th century regarding the ancient Egyptian city of Heracles have revealed the remains of a statue of Isis dating back to the 4th century BC.

The statue depicts the Egyptian goddess in an unusually sensual and subtle way. This is uncharacteristic of the sculptors of that area, because the image is detailed and feminine, symbolizing the combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms during the time of Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt.

Ancient Greek sculpture is the progenitor of all world art! Until now, the masterpieces of Ancient Greece attract millions of tourists and art connoisseurs who want to touch the timeless beauty and talent.

The art of Ancient Greece became the support and foundation on which the entire European civilization grew. The sculpture of Ancient Greece is a special topic. Without ancient sculpture there would be no brilliant masterpieces of the Renaissance, and the further development of this art is difficult to imagine. In the history of the development of Greek ancient sculpture, three large stages can be distinguished: archaic, classical and Hellenistic. Each one has something important and special. Let's look at each of them.

Archaic

This period includes sculptures created from the 7th century BC to the beginning of the 5th century BC. The era gave us figures of naked young warriors (kuros), as well as many female figures in clothes (koras). Archaic sculptures are characterized by some sketchiness and disproportion. On the other hand, each work of the sculptor is attractive for its simplicity and restrained emotionality. The figures of this era are characterized by a half-smile, which gives the works some mystery and depth.

"Goddess with Pomegranate", which is kept in the Berlin State Museum, is one of the best preserved archaic sculptures. Despite the external roughness and “wrong” proportions, the viewer’s attention is drawn to the hands of the sculpture, executed brilliantly by the author. The expressive gesture of the sculpture makes it dynamic and especially expressive.

"Kouros from Piraeus", which adorns the collection of the Athens Museum, is a later, and therefore more advanced, work of the ancient sculptor. Before the viewer is a powerful young warrior. A slight tilt of the head and hand gestures indicate a peaceful conversation that the hero is having. The disturbed proportions are no longer so striking. And the facial features are not as generalized as in early sculptures of the archaic period.

Classic

Most people associate sculptures of this particular era with ancient plastic art.

In the classical era, such famous sculptures as Athena Parthenos, Olympian Zeus, Discobolus, Doryphoros and many others were created. History has preserved for posterity the names of outstanding sculptors of the era: Polykleitos, Phidias, Myron, Scopas, Praxiteles and many others.

The masterpieces of classical Greece are distinguished by harmony, ideal proportions (which indicates excellent knowledge of human anatomy), as well as internal content and dynamics.

It is the classical period that is characterized by the appearance of the first nude female figures (the Wounded Amazon, Aphrodite of Cnidus), which give an idea of the ideal of female beauty in the heyday of antiquity.

Hellenism

Late Greek antiquity is characterized by a strong Eastern influence on all art in general and on sculpture in particular. Complex angles, exquisite draperies, and numerous details appear.

Oriental emotionality and temperament penetrates the calm and majesty of the classics.

Aphrodite of Cyrene, decorating the Roman Museum of Baths, is full of sensuality, even some coquetry.

The most famous sculptural composition of the Hellenistic era is Laocoon and his sons of Agesander of Rhodes (the masterpiece is kept in one of). The composition is full of drama, the plot itself suggests strong emotions. Desperately resisting the snakes sent by Athena, the hero himself and his sons seem to understand that their fate is terrible. The sculpture is made with extraordinary precision. The figures are plastic and real. The faces of the characters make a strong impression on the viewer.

ancient greek sculpture classic

Ancient Greek sculpture from the Classical period

Speaking about the art of ancient civilizations, first of all we remember and study the art of Ancient Greece, and in particular its sculpture. Truly, in this small beautiful country, this art form has risen to such a height that to this day it is considered a standard throughout the world. Studying the sculptures of Ancient Greece allows us to better understand the worldview of the Greeks, their philosophy, ideals and aspirations. In sculpture, as nowhere else, the attitude towards man, who in Ancient Greece was the measure of all things, is manifested. It is sculpture that gives us the opportunity to judge the religious, philosophical and aesthetic ideas of the ancient Greeks. All this allows us to better understand the reasons for the rise, development and fall of this civilization.

The development of Ancient Greek civilization is divided into several stages - eras. First, briefly, I will talk about the Archaic era, since it preceded the classical era and “set the tone” in sculpture.

The Archaic period is the beginning of the formation of ancient Greek sculpture. This era was also divided into early archaic (650 - 580 BC), high (580 - 530 BC), and late (530 - 480 BC). The sculpture was the embodiment of an ideal person. She exalted his beauty, his physical perfection. Early single sculptures are represented by two main types: the image of a naked young man - kouros and the figure of a girl dressed in a long, tight-fitting chiton - kora.

The sculpture of this era was very similar to the Egyptian ones. And this is not surprising: the Greeks, getting acquainted with Egyptian culture and the cultures of other countries of the Ancient East, borrowed a lot, and in other cases discovered similarities with them. Certain canons were observed in the sculpture, so they were very geometric and static: a person takes a step forward, his shoulders are straightened, his arms are lowered along his body, a stupid smile always plays on his lips. In addition, the sculptures were painted: golden hair, blue eyes, pink cheeks.

At the beginning of the classical era, these canons are still in effect, but later the author begins to move away from statics, the sculpture acquires character, and an event, an action, often occurs.

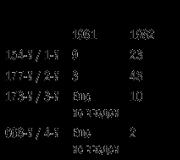

Classical sculpture is the second era in the development of ancient Greek culture. It is also divided into stages: early classic or strict style (490 - 450 BC), high (450 - 420 BC), rich style (420 - 390 BC .), Late Classic (390 - ca. 320 BC).

In the era of the early classics, a certain life rethinking takes place. The sculpture takes on a heroic character. Art is freeing itself from the rigid framework that shackled it in the archaic era; this is a time of searching for new, intensive development of various schools and directions, and the creation of diverse works. The two types of figures - kurosu and kore - are being replaced by a much greater variety of types; the sculptures strive to convey the complex movement of the human body.

All this takes place against the backdrop of the war with the Persians, and it was this war that so changed ancient Greek thinking. The cultural centers were shifted and are now the cities of Athens, the Northern Peloponnese and the Greek West. By that time, Greece had reached the highest point of economic, political and cultural growth. Athens took a leading place in the union of Greek cities. Greek society was democratic, built on the principles of equal activity. All men inhabiting Athens, except slaves, were equal citizens. And they all enjoyed the right to vote and could be elected to any public office. The Greeks were in harmony with nature and did not suppress their natural desires. Everything that was done by the Greeks was the property of the people. Statues stood in temples and squares, on palaestras and on the seashore. They were present on the pediments and in the decorations of temples. As in the archaic era, the sculptures were painted.

Unfortunately, Greek sculpture has come down to us mainly in rubble. Although, according to Plutarch, there were more statues in Athens than living people. Many statues have come down to us in Roman copies. But they are quite crude compared to the Greek originals.

One of the most famous sculptors of the early classics is Pythagoras of Rhegium. Few of his works have reached us, and his works are known only from mentions of ancient authors. Pythagoras became famous for his realistic depiction of human veins, veins and hair. Several Roman copies of his sculptures have survived: “Boy Taking out a Splinter”, “Hyacinth”, etc. In addition, he is credited with the famous bronze statue “Charioteer”, found in Delphi. Pythagoras of Rhegium created several bronze statues of the winning athletes of the Olympic and Delphic Games. And he owns the statues of Apollo - the Python Slayer, the Rape of Europa, Eteocles, Polyneices and the Wounded Philoctetes.

It is known that Pythagoras of Rhegium was a contemporary and rival of Myron. This is another famous sculptor of that time. And he became famous as the greatest realist and expert in anatomy. But despite all this, Myron did not know how to give life and expression to the faces of his works. Myron created statues of athletes - winners of competitions, reproduced famous heroes, gods and animals, and especially brilliantly depicted difficult poses that looked very realistic.

The best example of such a sculpture of his is the world-famous “Discobolus”. Ancient writers also mention the famous sculpture of Marsyas and Athena. This famous sculptural group has come down to us in several copies. In addition to people, Myron also depicted animals, his image of “Cows” is especially famous.

Myron worked mainly in bronze; his works have not survived and are known from the testimonies of ancient authors and Roman copies. He was also a master of toreutics - he made metal cups with relief images.

Another famous sculptor of this period is Kalamis. He created marble, bronze and chryselephantine statues, and depicted mainly gods, female heroic figures and horses. The art of Kalamis can be judged by the copy that has come down to us from a later time of a statue of Hermes carrying a ram that he made for Tanagra. The figure of the god himself is executed in an archaic style, with the immobility of the pose and the symmetry of the arrangement of the limbs characteristic of this style; but the ram carried by Hermes is already distinguished by some vitality.

In addition, the pediments and metopes of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia are among the monuments of ancient Greek sculpture of the early classics. Another significant work of early classics is the so-called “Throne of Ludovisi”. This is a three-sided marble altar depicting the birth of Aphrodite, on the sides of the altar are hetaeras and brides, symbolizing different hypostases of love or images of serving the goddess.

High classics are represented by the names of Phidias and Polykleitos. Its short-term heyday is associated with work on the Athenian Acropolis, that is, with the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon. The pinnacle of ancient Greek sculpture was, apparently, the statues of Athena Parthenos and Olympian Zeus by Phidias.

Phidias is one of the best representatives of the classical style, and about his significance it is enough to say that he is considered the founder of European art. The Attic school of sculpture, headed by him, occupied a leading place in the art of high classics.

Phidias had knowledge of the achievements of optics. A story has been preserved about his rivalry with Alcamenes: both were ordered statues of Athena, which were supposed to be erected on high columns. Phidias made his statue in accordance with the height of the column - on the ground it seemed ugly and disproportionate. The neck of the goddess was very long. When both statues were erected on high pedestals, Phidias’s correctness became obvious. They note the enormous skill of Phidias in the interpretation of clothing, in which he surpasses both Myron and Polycletus.

Most of his works have not survived; we can only judge them from descriptions of ancient authors and copies. Nevertheless, his fame was colossal. And there were so many of them that what was left was already a lot. The most famous works of Phidias - Zeus and Athena Parthenos were made in the chrysoelephantine technique - gold and ivory.

The height of the statue of Zeus, together with the pedestal, was, according to various sources, from 12 to 17 meters. Zeus's eyes were the size of an adult's fist. The cape that covered part of Zeus's body, the scepter with an eagle in the left hand, the statue of the goddess Nike in the right and the wreath on his head are made of gold. Zeus sits on a throne; four dancing Nikes are depicted on the legs of the throne. Also depicted were: centaurs, lapiths, the exploits of Theseus and Hercules, frescoes depicting the battle of the Greeks with the Amazons.

The Athena Parthenon was, like the statue of Zeus, huge and made in the chrysoelephantine technique. Only the goddess, unlike her father, did not sit on the throne, but stood at full height. “Athena herself is made of ivory and gold... The statue depicts her in full height in a tunic down to the very soles of her feet, on her chest is the head of Medusa made of ivory, in her hand she holds an image of Nike, approximately four cubits, and in the other hand - - a spear. At her feet lies a shield, and near her spear is a serpent; this snake is probably Erichthonius.” (Description of Hellas, XXIV, 7).

The goddess's helmet had three crests: the middle one with a sphinx, the side ones with griffins. As Pliny the Elder writes, on the outside of the shield there was a battle with the Amazons, on the inside there was a fight between gods and giants, and on Athena’s sandals there was an image of a centauromachy. The base was decorated with a Pandora story. The goddess's tunic, shield, sandals, helmet and jewelry are all made of gold.

On marble copies, the hand of the goddess with Nike is supported by a pillar; whether it existed in the original is the subject of much debate. Nika seems tiny, in reality her height was 2 meters.

Athena Promachos is a colossal image of the goddess Athena brandishing a spear on the Athenian Acropolis. Erected in memory of victories over the Persians. Its height reached 18.5 meters and towered above all the surrounding buildings, shining over the city from afar. Unfortunately, this bronze goddess did not survive to this day. And we know about it only from chronicle sources.

Athena Lemnia - a bronze statue of the goddess Athena, created by Phidias, is also known to us from copies. This is a bronze statue depicting a goddess leaning on a spear. It was named after the island of Lemnos, for whose inhabitants it was made.

The Wounded Amazon, a statue that took second place in the famous sculpting competition for the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus. In addition to the above sculptures, others are also attributed to Phidias, based on stylistic similarity: a statue of Demeter, a statue of Kore, a relief from Eleusis, Anadumen (a young man tying a bandage around his head), Hermes Ludovisi, Tiberian Apollo, Kassel Apollo.

Despite Phidias' talent, or rather divine gift, his relationship with the inhabitants of Athens was not at all warm. As Plutarch writes in his Life of Pericles, Phidias was the main adviser and assistant to Pericles (an Athenian politician, famous orator and commander).

“Since he was a friend of Pericles and enjoyed great authority with him, he had many personal enemies and envious people. They persuaded one of Phidias' assistants, Menon, to denounce Phidias and accuse him of theft. Phidias was burdened with envy of the glory of his works... When his case was examined in the People's Assembly, there was no evidence of theft. But Phidias was sent to prison and died there of illness.”

Polykleitos the Elder is an ancient Greek sculptor and art theorist, a contemporary of Phidias. Unlike Phidias, it was not so large-scale. However, his sculpture has a certain character: Polykleitos loved to depict athletes in a state of rest, and specialized in depicting athletes, Olympic winners. He was the first to think of posing the figures in such a way that they rested on the lower part of only one leg. Polykleitos knew how to show the human body in a state of balance - his human figure at rest or at a slow pace seems mobile and animated. An example of this is the famous statue of Polykleitos “Doriphoros” (spearman). It is in this work that Polykleitos’s ideas about the ideal proportions of the human body, which are in numerical proportion to each other, are embodied. It was believed that the figure was created on the basis of the provisions of Pythagoreanism, therefore in ancient times the statue of Doryphorus was often called the “canon of Polykleitos.” The forms of this statue are repeated in most of the works of the sculptor and his school. The distance from the chin to the crown of the head in the statues of Polykleitos is one-seventh, while the distance from the eyes to the chin is one-sixteenth, and the height of the face is one-tenth of the entire figure. Polykleitos is firmly connected with the Pythagorean tradition. “The Canon of Polykleitos” is a theoretical treatise by the sculptor, created by Polykleitos so that other artists could use it. Indeed, the Canon of Polykleitos had a great influence on European culture, despite the fact that only two fragments of the theoretical work have survived, information about it is fragmentary, and the mathematical basis has not yet been finally deduced.

In addition to the spearman, other works of the sculptor are known: “Diadumen” (“Young Man Tying a Bandage”), “Wounded Amazon”, a colossal statue of Hera in Argos. It was made in the chrysoelephantine technique and was perceived as a pandan to Phidias the Olympian Zeus, “Discophoros” (“Young Man Holding a Disk”). Unfortunately, these sculptures have survived only in ancient Roman copies.

At the “Rich Style” stage, we know the names of such sculptors as Alkamen, Agorakrit, Callimachus, etc.

Alkamenes, Greek sculptor, student, rival and successor of Phidias. Alkamenes was considered to be the equal of Phidias, and after the latter's death, he became the leading sculptor in Athens. His Hermes in the form of a herm (a pillar crowned with the head of Hermes) is known in many copies. Nearby, near the temple of Athena Nike, there was a statue of Hecate, which represented three figures connected by their backs. On the Acropolis of Athens, a group belonging to Alkamen was also found - Procne, raising a knife over her son Itis, who was seeking salvation in the folds of her clothes. In the sanctuary on the slope of the Acropolis there was a statue of a seated Dionysus belonging to Alkamen. Alkamen also created a statue of Ares for the temple on the agora and a statue of Hephaestus for the temple of Hephaestus and Athena.

Alkamenes defeated Agoracritus in a competition to create a statue of Aphrodite. However, even more famous is the seated "Aphrodite in the Gardens", at the northern foot of the Acropolis. She is depicted on many red-figure Attic vases surrounded by Eros, Peyto and other embodiments of the happiness that love brings. The head often repeated by ancient copyists, called "Sappho", was possibly copied from this statue. Alkamen's last work is a colossal relief with Hercules and Athena. Alkamenes probably died soon after this.

Agorakritos was also a student of Phidias, and, as they say, his favorite. He, like Alkamen, participated in the creation of the Parthenon frieze. The two most famous works of Agorakritos are the cult statue of the goddess Nemesis (remade by Athena after the duel with Alkamenes), donated to the Temple of Ramnos, and the statue of the Mother of the Gods in Athens (sometimes attributed to Pheidias). Of the works mentioned by ancient authors, only the statues of Zeus-Hades and Athena in Coronea undoubtedly belonged to Agorakritos. Of his works, only part of the head of the colossal statue of Nemesis and fragments of the reliefs that decorated the base of this statue have survived. According to Pausanias, the base depicted young Helen (daughter of Nemesis), with Leda who nursed her, her husband Menelaus and other relatives of Helen and Menelaus.

The general character of late classical sculpture was determined by the development of realistic tendencies.

Scopas is one of the largest sculptors of this period. Skopas, preserving the traditions of monumental art of high classics, saturates his works with drama; he reveals the complex feelings and experiences of a person. The heroes of Skopas continue to embody the perfect qualities of strong and valiant people. However, Skopas introduces themes of suffering and internal breakdown into the art of sculpture. These are the images of wounded warriors from the pediments of the Temple of Athena Aley in Tegea. Plasticity, a sharp, restless play of chiaroscuro emphasizes the drama of what is happening.

Skopas preferred to work in marble, almost abandoning the material favored by the masters of high classics - bronze. Marble made it possible to convey a subtle play of light and shadow, and various textural contrasts. His Maenad (Bacchae), which survives in a small, damaged antique copy, embodies the image of a man possessed by a violent impulse of passion. The dance of the Maenad is swift, the head is thrown back, the hair falls in a heavy wave onto the shoulders. The movement of the curved folds of her chiton emphasizes the rapid impulse of the body.

The images of Skopas are either deeply thoughtful, like the young man from the tombstone of the Ilissa River, or lively and passionate.

The frieze of the Halicarnassus Mausoleum depicting the battle between the Greeks and the Amazons has been preserved in the original.

The impact of Skopas's art on the further development of Greek plastic arts was enormous, and can only be compared with the impact of the art of his contemporary, Praxiteles.

In his work, Praxiteles turns to images imbued with the spirit of clear and pure harmony, calm thoughtfulness, and serene contemplation. Praxiteles and Scopas complement each other, revealing the various states and feelings of a person, his inner world.

Depicting harmoniously developed, beautiful heroes, Praxiteles also reveals connections with the art of high classics, however, his images lose the heroism and monumental grandeur of the works of the heyday, but acquire a more lyrically refined and contemplative character.

Praxiteles’ mastery is most fully revealed in the marble group “Hermes with Dionysus”. The graceful curve of the figure, the relaxed resting pose of the young slender body, the beautiful, spiritual face of Hermes are conveyed with great skill.

Praxiteles created a new ideal of female beauty, embodying it in the image of Aphrodite, who is depicted at the moment when, having taken off her clothes, she is about to enter the water. Although the sculpture was intended for cult purposes, the image of the beautiful naked goddess was freed from solemn majesty. "Aphrodite of Cnidus" caused many repetitions in subsequent times, but none of them could compare with the original.

The sculpture of “Apollo Saurocton” is an image of a graceful teenage boy aiming at a lizard running along a tree trunk. Praxiteles rethinks mythological images; features of everyday life and elements of the genre appear in them.

If in the art of Scopas and Praxiteles there are still tangible connections with the principles of high classical art, then in the artistic culture of the last third of the 4th century. BC e., these ties are increasingly weakened.

Macedonia acquired great importance in the socio-political life of the ancient world. Just as the war with the Persians changed and rethought the culture of Greece at the beginning of the 5th century. BC e. After the victorious campaigns of Alexander the Great and his conquest of the Greek city-states, and then the vast territories of Asia that became part of the Macedonian state, a new stage in the development of ancient society began - the period of Hellenism. The transitional period from the late classics to the Hellenistic period proper is distinguished by its peculiar features.

Lysippos is the last great master of the late classics. His work unfolds in the 40-30s. V century BC e., during the reign of Alexander the Great. In the art of Lysippos, as well as in the work of his great predecessors, the task of revealing human experiences was solved. He began to introduce more clearly expressed features of age and occupation. What is new in Lysippos’s work is his interest in the characteristically expressive in man, as well as the expansion of the visual possibilities of sculpture.

Lysippos embodied his understanding of the image of man in the sculpture of a young man scraping sand off himself after a competition - “Apoxiomenes”, whom he depicts not in a moment of exertion, but in a state of fatigue. The slender figure of the athlete is shown in a complex turn, which forces the viewer to walk around the sculpture. The movement is freely deployed in space. The face expresses fatigue, the deep-set, shadowed eyes look into the distance.

Lysippos skillfully conveys the transition from a state of rest to action and vice versa. This is the image of Hermes resting.

The work of Lysippos was of great importance for the development of portraiture. The portraits he created of Alexander the Great reveal a deep interest in revealing the spiritual world of the hero. Most notable is the marble head of Alexander, which conveys his complex, contradictory nature.

The art of Lysippos occupies the border zone at the turn of the classical and Hellenistic eras. It is still true to classical concepts, but it is already undermining them from the inside, creating the basis for a transition to something else, more relaxed and more prosaic. In this sense, the head of a fist fighter is indicative, belonging not to Lysippos, but, possibly, to his brother Lysistratus, who was also a sculptor and, as they said, was the first to use masks taken from the model’s face for portraits (which was widespread in Ancient Egypt, but completely alien to Greek art). It is possible that the head of a fist fighter was also made using the mask; it is far from the canon, far from the ideal ideas of physical perfection that the Hellenes embodied in the image of an athlete. This winner in a fist fight is not at all like a demigod, just an entertainer for an idle crowd. His face is rough, his nose is flattened, his ears are swollen. This type of “naturalistic” images subsequently became common in Hellenism; an even more unsightly fist fighter was sculpted by the Attic sculptor Apollonius already in the 1st century BC. e.

What had previously cast shadows on the bright structure of the Hellenic worldview came at the end of the 4th century BC. e.: decomposition and death of the democratic polis. This began with the rise of Macedonia, the northern region of Greece, and the virtual seizure of all Greek states by the Macedonian king Philip II.

Alexander the Great tasted the fruits of the highest Greek culture in his youth. His teacher was the great philosopher Aristotle, and his court artists were Lysippos and Apelles. This did not prevent him, having captured the Persian state and taken the throne of the Egyptian pharaohs, from declaring himself a god and demanding that he be given divine honors in Greece as well. Unaccustomed to eastern customs, the Greeks chuckled and said: “Well, if Alexander wants to be a god, let him be” - and officially recognized him as the son of Zeus. However, Greek democracy, on which its culture grew, died under Alexander and was not revived after his death. The newly emerged state was no longer Greek, but Greek-Eastern. The era of Hellenism has arrived - the unification under the auspices of the monarchy of Hellenic and Eastern cultures.

Outstanding sculptors of Ancient Greece

Features of ancient Greek sculpture The main theme is the image of a person, admiration for the beauty of the human body.

Archaic sculpture: Kouros - naked athletes. Installed near temples; They embodied the ideal of male beauty; They look alike: young, slender, tall. Kouros. 6th century BC

Archaic sculpture: Kory - girls in tunics. They embodied the ideal of female beauty; They look alike: curly hair, a mysterious smile, the embodiment of sophistication. Bark. 6th century BC

GREEK CLASSICAL SCULPTURE End of V-IV centuries. BC e. - the period of the turbulent spiritual life of Greece, the formation of the idealistic ideas of Socrates and Plato in philosophy, which developed in the fight against the materialistic philosophy of the Democrat, the time of the formation of new forms of Greek fine art. In sculpture, the masculinity and severity of the images of strict classics is replaced by an interest in the spiritual world of man, and a more complex and less straightforward characteristic of it is reflected in plastic.

Greek sculptors of the classical period: Polykleitos Myron Scopas Praxiteles Lysippos Leochares

Polykleitos Polykleitos. Doryphoros (spearman). 450-440 BC Roman copy. National Museum. Naples The works of Polykleitos became a real hymn to the greatness and spiritual power of Man. The favorite image is a slender young man with an athletic build. There is nothing superfluous in him, “nothing in excess”; his spiritual and physical appearance are harmonious.

Doryphoros has a complex pose, different from the static pose of the ancient kouroi. Polycletus was the first to think of posing the figures in such a way that they rested on the lower part of only one leg. In addition, the figure seems mobile and animated, due to the fact that the horizontal axes are not parallel (the so-called chiasmus). “Doripho?r” (Greek ????????? - “Spear-bearer”) - one of the most famous statues of antiquity, embodies the so-called. Canon of Polykleitos.

The canon of Polykleitos Doryphoros is not an image of a specific winning athlete, but an illustration of the canons of the male figure. Polykleitos set out to accurately determine the proportions of the human figure, according to his ideas about ideal beauty. These proportions are in numerical relation to each other. “They even assured that Polykleitos performed it on purpose, so that other artists would use it as a model,” wrote a contemporary. The work “The Canon” itself had a great influence on European culture, despite the fact that only two fragments of the theoretical work have survived.

Canon of Polykleitos If we recalculate the proportions of this Ideal Man for a height of 178 cm, the parameters of the statue will be as follows: 1. neck volume - 44 cm, 2. chest - 119, 3. biceps - 38, 4. waist - 93, 5. forearms - 33 , 6. wrists - 19, 7. buttocks - 108, 8. hips - 60, 9. knees - 40, 10. shins - 42, 11. ankles - 25, 12. feet - 30 cm.

Polykleitos "Wounded Amazon"

Myron Myron - Greek sculptor of the mid-5th century. BC e. The sculptor of the era immediately preceding the highest flowering of Greek art (6th century - early 5th century) embodied the ideals of the strength and beauty of Man. He was the first master of complex bronze castings. Miron. Discus thrower.450 BC. Roman copy. National Museum, Rome

Miron. “Disco thrower” The ancients characterize Myron as the greatest realist and expert in anatomy, who, however, did not know how to give life and expression to faces. He depicted gods, heroes and animals, and with special love he reproduced difficult, fleeting poses. His most famous work is “The Disco Thrower,” an athlete intending to throw a discus, a statue that has survived to this day in several copies, of which the best is made of marble and is located in the Massami Palace in Rome.

"Disco thrower" by Myron at the Copenhagen Botanical Garden

Discus thrower. Miron

Sculptural creations of Skopas Skopas (420 - c. 355 BC), a native of the island of Paros, rich in marble. Unlike Praxiteles, Skopas continued the traditions of high classics, creating monumental heroic images. But from the images of the 5th century. they are distinguished by the dramatic tension of all spiritual forces. Passion, pathos, strong movement are the main features of Skopas’ art. Also known as an architect, he participated in the creation of a relief frieze for the Halicarnassus mausoleum.

In a state of ecstasy, in a violent outburst of passion, the Maenad is depicted by Scopas. The companion of the god Dionysus is shown in a rapid dance, her head is thrown back, her hair has fallen to her shoulders, her body is curved, presented in a complex angle, the folds of her short chiton emphasize the violent movement. Unlike the sculpture of the 5th century. The Skopas maenad is designed to be viewed from all sides. Skopas. Maenad Sculptural creations of Skopas

Skopas. Battle with the Amazons Sculptural creations of Skopas Also known as an architect, he participated in the creation of a relief frieze for the Halicarnassus mausoleum.

Praxiteles Born in Athens (c. 390 - 330 BC) Inspirational singer of female beauty.

The statue of Aphrodite of Knidos is the first depiction of a nude female figure in Greek art. The statue stood on the shore of the Knidos peninsula, and contemporaries wrote about real pilgrimages here to admire the beauty of the goddess preparing to enter the water and throwing off her clothes on a nearby vase. The original statue has not survived. Sculptural creations of Praxiteles Praxiteles. Aphrodite of Knidos

Sculptural creations of Praxiteles In the only marble statue of Hermes (the patron of trade and travelers, as well as the messenger, “courier” of the gods) that has come down to us in the original of the sculptor Praxiteles, the master depicted a beautiful young man in a state of peace and serenity. He looks thoughtfully at the baby Dionysus, whom he holds in his arms. The masculine beauty of an athlete is replaced by a beauty that is somewhat feminine, graceful, but also more spiritual. The statue of Hermes retains traces of ancient coloring: red-brown hair, a silver bandage. Praxiteles. Hermes. Around 330 BC e.

Sculptural creations of Praxiteles

Lysippos the Great sculptor of the 4th century. BC. (370-300 BC). He worked in bronze, because sought to capture images in a fleeting rush. He left behind 1,500 bronze statues, including colossal figures of gods, heroes, and athletes. They are characterized by pathos, inspiration, emotionality. The original has not reached us. Court sculptor of A. Macedonian Marble copy of the head of A. Macedonian

Lysippos. Hercules fighting a lion. 4th century BC Roman copy Hermitage, St. Petersburg This sculpture conveys with amazing skill the passionate intensity of the duel between Hercules and the lion. Sculptural creations of Lysippos

Sculptural creations of Lysippos Lysippos sought to bring his images as close as possible to reality. Thus, he showed athleticism not at the moment of the highest tension of forces, but, as a rule, at the moment of their decline, after the competition. This is exactly how his Apoxyomenos is represented, cleaning off the sand from himself after a sports fight. He has a tired face and his hair is matted with sweat. Lysippos. Apoxyomenos. Roman copy, 330 BC

The captivating Hermes, always fast and lively, is also represented by Lysippos as if in a state of extreme fatigue, briefly sitting on a stone and ready to run further in the next second in his winged sandals. Sculptural creations of Lysippos Lysippos. "Resting Hermes"

Lysippos created his own canon of proportions of the human body, according to which his figures are taller and slimmer than those of Polykleitos (the size of the head is 1/9 of the figure). Sculptural creations of Lysippos Lysippos. "Hercules of Farnese"

Leohar Leohar. Apollo Belvedere. 4th century BC Roman copy. Vatican Museums His work is an excellent attempt to capture the classical ideal of human beauty. His works contain not only the perfection of images, but also the skill and technique of execution. Apollo is considered one of the best works of Antiquity.

Sculptural masterpieces of the Hellenistic era

Greek sculpture So, in Greek sculpture, the expressiveness of the image was in the entire human body, his movements, and not just in the face. Despite the fact that many Greek statues did not preserve their upper part (for example, “Nike of Samothrace” or “Nike Untying Sandals” came to us without a head, we forget about this when looking at the holistic plastic solution of the image. Because the soul and the body was thought of by the Greeks as an indivisible unity, then the bodies of Greek statues are unusually spiritualized.

Nike of Samothrace Nike of Samothrace 2nd century BC Louvre, Paris Marble The statue was erected on the occasion of the victory of the Macedonian fleet over the Egyptian in 306 BC. e. The goddess was depicted as if on the bow of a ship, announcing victory with the sound of a trumpet. The pathos of victory is expressed in the swift movement of the goddess, in the wide flap of her wings.

Nike of Samothrace

Nike Untying her Sandal The goddess is depicted untying her sandal before entering the Marble Temple. Athens

Venus de Milo On April 8, 1820, a Greek peasant from the island of Melos named Iorgos, while digging the ground, felt that his shovel, clinking dully, came across something solid. Iorgos dug nearby - the same result. He took a step back, but even here the spade did not want to enter the ground. First Iorgos saw a stone niche. It was about four to five meters wide. In the stone crypt, to his surprise, he found a marble statue. This was Venus. Agesander. Venus de Milo. Louvre. 120 BC

Laocoon with his sons Agesander, Athenodorus, Polydorus

Laocoon and his sons Laocoon, you have not saved anyone! You are not a savior of either the city or the world. Reason is powerless. Proud Three's mouth is destined; the circle of fatal events closed in a suffocating crown of snake coils. Horror on the face, the pleas and groans of your child; the other son was silenced by poison. Your fainting. Your wheezing: “Let me be...” (...Like the bleating of sacrificial lambs Through the darkness, both piercing and subtle!..) And again - reality. And poison. They are stronger! In the snake's mouth, anger blazes powerfully... Laocoon, and who heard you?! Here are your boys... They... are not breathing. But every Troy has its own horses.

Phidias and the Parthenon friezes

Statue of Zeus by Phidias at Olympia

His images are sublime and beautiful. Phidias

Phidias Phidias. Athena statue

check yourself