Settlements and dwellings of the Chuvash. Food

The main types of settlements are villages and hamlets. The earliest types of settlement are riverine and ravine, the layouts are cumulus-cluster (in the northern and central regions) and linear (in the south). In the north, the village is typically divided into ends, usually inhabited by related families. The street layout extends from the 2nd floor. 19th century

The traditional hut was placed in the center of the front yard with an entrance to the east and windows to the south, heated with a black adobe stove near the rear blank wall. There were bunks along the walls. From the 2nd half of the 19th century. Dwellings of the Central Russian type with a three-part structure are spreading: hut - canopy - cage. Windows are cut into 3 walls; the internal layout is similar to Russian: red corner, bunk, benches along the walls; The kitchen is separated by a partition. To the beginning XX century the chicken stove is replaced by a Russian stove with a chimney and plates, while the traditional hearth with a suspended or embedded boiler is preserved. Later, Dutch ovens became widespread. The roof is 2-, in the south often 4-slope, covered with straw, shingles or planks. The house is decorated with polychrome painting, saw-cut carvings, applied decorations, the so-called. “Russian” gate with a gable roof on 3-4 pillars - bas-relief carvings, later painting. 80% of rural Chuvash live in traditional huts.

There is an ancient log building (originally without a ceiling or windows, with an open hearth), serving as a summer kitchen. Cellars and baths are common. Traditional local differences in housing and the layout of the estate are preserved: among the upper Chuvash, the residential house and outbuildings are connected in an L- or U-shape, large open courtyards are common; among the lower Chuvash, the cage is, as a rule, separated from the house, outbuildings are located in the corner opposite from the house courtyard, dominated by bright polychrome coloring, abundant decorative elements in the external decoration. A modern rural house has four or five walls with an internal layout of living space, a veranda, a front porch, and a mezzanine. The interior retains traditional features: in the front corner there are a table, chairs, a sofa or benches, the bed is often separated by a curtain. Homespun carpets (palaces) and traditional embroidery are used.

Development and improvement of cities in the 16th-19th centuries.

There is no such question

Food culture, traditional dishes.

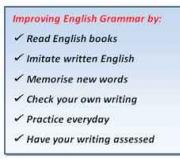

The main grain plants consumed as food are rye, barley, oats, millet, buckwheat, known from Arab sources and archaeological data, even in Volga Bulgaria.

The main place was given to dishes made from rye flour, sour bread and numerous cookies, ranging from hearth cakes to traditional pies with meat or fish filling, khuplu. Flour, cereals and oatmeal made from oats, wheat, spelt and barley were also used.

Chuvash national cuisine includes a significant number of meat dishes. They ate beef, lamb, horse meat (among the lower Chuvash), and poultry. The traditional Chuvash treat sharttan is a sheep stomach stuffed with meat. We also cooked homemade sausage. Dairy products were widely used, mainly sour milk turah, churning uyran, as well as cottage cheese in the form of chykyt cheese curds. Butter and eggs were eaten in small quantities: along with grain, they were the main commercial products of the peasant economy. Game was occasionally consumed, mainly hare meat. Residents of riverine villages ate fish. Delicious and nutritious dishes of national cuisine were prepared only on holidays. The Chuvash family mainly ate traditional yashka soup with homemade noodles, which were only occasionally cooked in meat or fish broth, as well as uiran, boiled potatoes, porridges, and jelly. Porridge, soup with dumplings, pancakes, flat cakes, as well as eggs and drinks were an obligatory attribute of Chuvash religious rites.

Among the sweets, the Chuvash consumed honey, which was also used for honey drink and honey mash. The intoxicating drink was beer made from barley or rye malt.

The traditional food system of the Chuvash, fitting into the framework of the Volga model, also has some specificity, which indicates the dominant nature of the ethnogenetic proximity of the Chuvash to the world of pastoral peoples of Asia.

One group of their foods and dishes has a continuous connection with the culinary traditions of ancient nomads, as well as Turkic and partially Iranian-speaking peoples of Asia, the other was formed in relatively later periods already in the middle Volga and Urals as a result of cultural and genetic mutual influence with local Finno-Ugric peoples (porridge, some flour products), as well as Russian.

35. Family rituals: maternity (naming, baptism), wedding rituals.

1) Traditions and rituals in a Chuvash wedding.

Dating and choosing the bride and groom.

According to the traditions of many nations, it was impossible to choose a wife or husband from relatives. Among the Chuvash, this ban extended to the seventh generation. For example, seventh cousins were not allowed to marry. This prohibition is due to the fact that in consanguineous marriages, children are often born sick. Therefore, Chuvash boys looked for brides in neighboring and distant villages.

To get to know young people, various gatherings, games, and holidays were organized, common to several villages. They looked especially carefully at future wives and husbands doing joint work: haymaking, nim, etc.

When a guy announced his desire to get married, the parents first of all found out what kind of family the bride was from, whether she was healthy, whether she was hardworking enough, whether she was smart, what her character was, what her appearance was, etc.

To meet the bride's family and make a preliminary arrangement, matchmaking, the young man's parents sent matchmakers. A few days later, the groom’s parents and relatives came to the bride’s house for the final matchmaking of the bride. They brought gifts: beer, cheese, various cookies. Relatives, usually the eldest in the family, also gathered from the bride's side. Before the treat, they opened the door slightly and prayed with pieces of bread and cheese in their hands. Then the feast, songs, fun began. On the same day, the bride gave gifts to her future relatives: towels, surpans, shirts and treated them to beer, in return they put several coins in the empty ladle. During one of these visits, the matchmakers agreed on the wedding day and the amount of the bride price and dowry.

A few days before the wedding, the groom's parents once again came to the bride's house to finalize the terms of the wedding.

Money, food for a wedding, skins for a fur coat, etc. were given as bridewealth. And the dowry included various clothes, scarves, towels, feather beds, chests, pets: a foal, a cow, sheep, geese, a hen and chicks.

The senior groom was chosen from the groom's close relatives - a kind, cheerful man, a joker and a talker, who perfectly remembers all the details of the wedding ritual. Usually he negotiated with the bride's parents. The younger groom was chosen from among the groom's young relatives.

Wedding preparations

Everywhere, a Chuvash wedding began almost simultaneously in both the groom’s house and the bride’s house, then the weddings were joined in the bride’s house - the groom came and took her to his place, and the wedding ended in the groom’s house. In general, wedding celebrations took place over several days and were often held within a week.

As always, before special celebrations, they had a bathhouse, dressed in the best elegant clothes, festive hats and jewelry. Among relatives or good friends, special people were chosen who organized the wedding celebration and carried out special assignments. The wedding director was chosen from both the groom's and the bride's sides.

The bride bowed to her parents, the father and mother blessed their daughter.

According to Chuvash traditions, both the bride and groom were seated on pillows with special embroidered patterns. The Russians put newlyweds on fur skins so they could live richly.

The groom was brought into the house, he bowed to his parents, and they blessed him.

A mandatory wedding ritual was the bride's wearing of a female headdress - surpan khushpu.

The last wedding ceremony was the ceremony of the bride going to fetch water, which could also be carried out in different ways. The bride, young people, and relatives went to the spring. They could throw coins into the water and pronounce the necessary words. The bride (or her husband's relative) collected water three times and the bucket was overturned three times. For the fourth time, the bride brought water to the house. She used this water to cook dumpling soup or other dish. Cooking by the daughter-in-law and treating new relatives meant her entry into her husband's clan.

HOUSING– built in accordance with nature. and socio-economic. living conditions, level of development of architecture, construction to meet housing needs, cultural component, including related ones. from ethnic. specifics. In individual Housing - technology, layout, interior - reflected traditionally. elements of culture. The functionality has been known since ancient times. division of housing into winter and summer, the origins of which go back to stable, permanent housing and portable, collapsible housing. Chuvash materials. Vocabularies, folklore, legends, and embroidery patterns indicate that the ancient housing of the Chuvash ancestors was a yurt. In writing sources near the Volga. Bulgarians, along with the Derevians. houses and adobe. J., felt yurts were also recorded. However, the Chuvash tradition of organizing yurts has not been preserved. Perhaps the rudiments of the ancient dwelling - tent-wagon (the main type of housing in the steppe zone) - are a leather-covered thuja k™mi (wedding wagon) and a wagon for spending the night during haymaking and grain harvest (it was covered with leather or rough canvas). Since ancient times, the semi-dugout served as a stationary dwelling; it dominated the forest-steppe. and step. stripes among the settled population of the Saltovo-Mayak culture; in the 2nd half. 1 thousand it also appears in the southern regions of the Kama region, but also existed in the late Middle Ages. In particular, due to the turbulent situation in the 2nd half. 14th – 15th centuries the population of Trans-Kama mainly built half-dugouts, the walls of which were strengthened with wooden blocks. Above-ground adobe houses of round or oval shape with a conical roof were typical among the Bulgarians and, perhaps, preceded the log house, which was built in the Middle Ages. The Volga region has been known since the 2nd half. 1 thousand AD

Chuvash. peasants architecture dates back to the time when the main builder. the material was wood (mid 1st millennium AD), while the roots were ornamental. The motives lie deeper. The Chuvash log hut lasts a long time. time it was single-chamber, in the 17th–19th centuries. it was built with a canopy at the entrance, with a porch and, less often, with a canopy. In the 18th century or previously there were three chambers. F. hut + canopy + hut (one of the huts served as a clean half). In the 2nd half. 19th century single-chamber housing gave way to two-chamber housing (a hut with a closed entrance), more typical for the forest-steppe. zone, and a three-chamber one (a hut with a canopy and a cage), which was more common in the forest zone. The introduction of these types of housing was associated both with the development of construction. technology, as well as the redevelopment of settlements - replacing the cumulus plan with a street plan. Wealthy peasants built the so-called round houses - wide side towards the street, with a hallway with a hallway. like along a long wall. Houses were placed with their facade facing the street along one line (in the old days they were located in the middle of the courtyard or along the perimeter of nested courtyards). In the three-chamber connection, hut + canopy + cage (two-story barn), the cage or second floor of the barn was used as a summer living room (cage-bedroom). In the forest zone (in particular, in Kozmodemyan. u.) houses were built with a high roof, basement, and semi-basement. floor. Five-walled, which appeared in the 2nd half. 19th century, spread from the middle. 20th century; for forest-steppe. zones (ethno-territorial groups) a hut with a cut-out is more typical. A five-wall house with a truss and a cross house are variants of multi-chambers. wooden houses that had little share in the total housing stock.

In the beginning. 20th century J. had wood. the foundation (pillars), log houses (10–15 crowns) were cut into a corner (“into a bowl”) from coniferous or linden logs, the frame crown was made from oak. Rafters. the roof replaced the male, which predominated until the gray. 19th century In the forest zone, the main material for covering was wood (shingles, bast, shingles, planks), in the forest-steppe. – straw. The four-walled building had 3–6 windows with single or double-leaf shutters (in the mid-19th century there were 1–2 small slanted windows without frames and glass windows). Old home orientation traditions, for example, to the east were no longer observed. in the end 19 – beginning 20th centuries has undergone a number of changes.

At the turn of the 19th–20th centuries. consumption of construction workers has increased. material. Wealthy peasants hired carpenters, carvers, joiners, masons; into peasants. innovations are being introduced into construction equipment. In the beginning. 20th century in the development of peasants. In the 1960s, a new type of housing appeared - chul ®urt (stone house), built of brick, incorporating classical elements into the architectural design. In the 1920s Wonderful examples of external decoration appeared with the spread of new types of housing, such as a five-walled house, a “round” house, and a stone house. The art of ornamentation developed. carvings of elements of the facade of the house: platbands, cornice, pediment, front porch, gate. Political situation in the 1930s. led to a slowdown in the development of architecture.

Development of life in the 2nd half. 20th century happened on inherited. traditions and their combination with innovations. Five-walled houses and houses with trusses became the main types of housing; this situation persisted in the beginning. 21st century Log houses have more character. sign for the zone adjacent to forests; Logging technology is widely used in modernized construction. large houses and summer houses in the con. 20 – beginning 21st centuries New progressives are being introduced. and rational. bricklaying methods. The share of brick houses is 40–50%. Large houses are being built with a large number of windows, improved. architecture appearance - with an attic, balcony, porch, tower, new roof shapes (attic, asymmetrical, multi-component), figured masonry of walls, cornice and platband, saw-cut carvings. Since the 1980s There has been a tendency towards the construction of residential and other premises under one roof. A two-story building is being built. Houses.

In Zh. Chuvash development is a builder. technology and architecture. elements had the same trends as other peoples of the Volga and Urals regions. All R. 19th century were almost the only ones. exponent of decorative design of buildings. The residential building, unlike the gate, which did not face the outside space, was little decorated with carvings; note Changes in Zh.'s appearance began to occur with the installation of the hut facing the street. Change in structural and morphological The signs concerned the structure of the roof, windows, intimacy, and interior. Elements of art. design that spread to the end. 19th century, were a dormer and a dormer window with a platband, piers (boards covering the front end slope of the roof), overlay patterns on the gable field, a cornice, platbands and shutters, cladding of corners and walls. Along with dugouts and sculptures. cutting and overhead threads were introduced using threads. Overhead figures - squares, rhombuses, round rosettes - were used instead of old carved rosettes. New traditions were consolidated in the 1920s. Examples of ornamentation from this period have been recorded , they indicate a significant level of Chuvash skill. carvers. In the external design of the house in the 2nd half. 20th century sawn (openwork, silhouette, overlay) carving and mosaic were used. wall cladding, expanded iron, plaster, whitewashing and painting, stucco, carving on wet plaster, figures. brickwork. Many decorative options have been developed for housing, reflecting quantitative and qualitative characteristics. and local. peculiarities. Abundance of decorative elements, large-patterned piece sets, wide cornice board with overlay. patterns, small architectures. shapes (attics of summer houses, gates), bright polychrome. coloring is a characteristic characteristic of the southwest. regions of Chuvashia. To the northwest. Part of the decorative feature is, in particular, finely patterned carvings reminiscent of filigree. embroidery of Chuvash riding people, gates with carved and painted decorations of pillars in the old style. style, etc. Clear decorative. The ensemble consists of a residential building, a summer house and a gate. For ethnoterritorial. groups of Chuvash forest-steppe. zones (Samara and Saratov regions, Bashkortostan) character. element is the exterior finishing. walls of houses - coating, plaster, whitewashing. In a number of areas, especially in the east, the story became widespread. painting in enamel and oil paints.

With the emergence of cities, cities were built. J., which was originally made of wood. and had practically no differences from the rural one. Later, stone houses appeared for the wealthy. trading people, representing the 2nd floor. chambers, in which the residential floor was located above the subcellular utility floor. In some merchant houses, con. 19th century On the ground floor there were shops, restaurants and taverns.

In the beginning. 20th century In connection with the development of industry in cities, a new type of housing appeared - hired, character. a feature of which was a number of more or less identical residential cells, united. general communications: corridor or stairs. In the 1920s–30s. in the cities of Chuvashia, 2nd floors were built. 6–8 apartments. wooden houses and barracks. Sharpness of dwellings. problems required the introduction of industrial. methods of construction and unification of types of housing. For this purpose, in 1929–31. A plant for the production of frame parts was built in Kozlovka. American houses. type for 8 apartments. In con. 1920s - early 1930s apartments began to be built. individual houses made of brick-pich. projects (for example, 18-apartment “House of Professorship” on K. Marx Street in Cheboksary, 1932), then, with the development of economic construction. sectional houses - according to standard ones.

From ser. 1960s massive construction of the 5th floor began. houses made of prefabricated reinforced concrete. panels according to a series of standard projects. The houses had 1, 2 and 3 rooms. apartments with useful area from 31 to 57 m2 with full engineer. landscaping. In the beginning. 1970s The construction of a new series of large panels has been mastered. houses, which has a wide range of block sections with more comfort. apartments, which made it possible to solve the layout of neighborhoods in a picturesque and unconventional way. Pre-schools were built in them at the same time as housing. institutions, schools, trade and public service enterprises, cultural institutions. First 9th floor. a residential building of this series was built in Novocheboksarsk in 1974. At the end. 1970s - early 1980s Work has been carried out to unify large-panel products. housing construction and improvement of planning. solutions for apartments, as a result of which a regional was created. a series of standard designs for residential buildings and a block section was introduced. method of their design and construction (prize of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, 1983). The apartments have increased living space, the size of kitchens, hallways, and bathrooms.

In the beginning. 1980s monolith housing construction has been introduced. concrete. The first monolith. residential building with 79 apartments (1-, 3-, 4-room apartments, total area from 36 to 87 m2) erected in Cheboksary in 1984. Along with large panels. and monolith. houses are built from brick, both standard and individual. projects, taking into account the specific features. family and site planning.

The quality of housing is determined by the state. nor-ma-tivami. From the time of. Urban housing is designed taking into account the occupancy of an apartment by one family. Apartments in state buildings. and municipal. The housing stock has living rooms and utility rooms. premises: kitchen, front room, bathroom, restroom, pantry; apartments in buildings of other forms of ownership, in addition - additional. premises (children's room, dining room, office, etc.).

To create the most favorable. living conditions for villages. population in the 1960s work has begun on . Along with the traditional Residential buildings began to be built on 2-3 floors. sectional home city. type, equipped. centralized plumbing, sewerage and heating. Experiments were conducted to select the most rational one. types of villages J. (see ). Builder industry Chuvash. Rep. The production of products for complete assembly was mastered. estate houses type for 1–2 apartments and sections. houses with 12, 18 and 27 apartments. Significant things happened. changes in traditional G. Houses began to be built of brick, 1–2 floors with a large set of utility rooms. buildings The arch-tech tour has changed. image of the village G. All houses are electrified, gasified approx. 90% (2006).

Builder development. bases and individual-dual. construction allowed to increase the number of dwellings to 2005. republic fund up to 26.1 million m2, housing availability – up to 20 m2 for 1 person

Mordva Erzya Moksha Karatai (Tatar influence) Teryukhane (Russian influence) Shoksha (Russian influence)

Mordva Erzya Moksha Karatai (Tatar influence) Teryukhane (Russian influence) Shoksha (Russian influence)

Origin of the name The ethnonym “Mordovians” is not the self-name of the people. Iranian language (“mord” - person, man). The first written mention of the Mordovians dates back to the middle of the 6th century AD. The Gothic historian Jordanes, in his work “On the Origin and Deeds of the Getae” (“Getica”), names the “Mordens” among the tribes conquered by the Gothic king Germanaric.

Origin of the name The ethnonym “Mordovians” is not the self-name of the people. Iranian language (“mord” - person, man). The first written mention of the Mordovians dates back to the middle of the 6th century AD. The Gothic historian Jordanes, in his work “On the Origin and Deeds of the Getae” (“Getica”), names the “Mordens” among the tribes conquered by the Gothic king Germanaric.

Purgasova Rus' In Russian chronicles of the first half of the 13th century. mention is made of the Mordovian “Purgas Rus'”, headed by the inyazor (“great master” - erz.) Purgas, whose policy was focused on the Bulgarians.

Purgasova Rus' In Russian chronicles of the first half of the 13th century. mention is made of the Mordovian “Purgas Rus'”, headed by the inyazor (“great master” - erz.) Purgas, whose policy was focused on the Bulgarians.

Settlements and dwellings riverine and riverine type of settlement watershed type of settlement are rare

Settlements and dwellings riverine and riverine type of settlement watershed type of settlement are rare

The nature of the layout According to the nature of the layout, the Mordovian villages of the Volga region were divided into ordinary, end, street, random quarter-street.

The nature of the layout According to the nature of the layout, the Mordovian villages of the Volga region were divided into ordinary, end, street, random quarter-street.

Street development The street consisted of one row of houses, in front of the windows of which there were outbuildings - huts, barns and baths. This is the layout of one of the ends of the village. Maly Tolkai (Pokhvistnevsky district), known as troxpe.

Street development The street consisted of one row of houses, in front of the windows of which there were outbuildings - huts, barns and baths. This is the layout of one of the ends of the village. Maly Tolkai (Pokhvistnevsky district), known as troxpe.

The dwelling of the Mordovians is a smoke hut, which was heated “in black.” The dwelling of the Mordovians was two-partitioned and three-partitioned.

The dwelling of the Mordovians is a smoke hut, which was heated “in black.” The dwelling of the Mordovians was two-partitioned and three-partitioned.

The house consisted of a residential hut (kud m., kudo e.) and a passage (kudongol m., kudykelks e.). The three-part house was complemented by an upper room.

The house consisted of a residential hut (kud m., kudo e.) and a passage (kudongol m., kudykelks e.). The three-part house was complemented by an upper room.

Construction technology The log houses were low - up to 13 crowns. They were usually placed without a foundation or on low wooden posts. Many houses were made of adobe. Sometimes such houses were built using formwork - plank walls.

Construction technology The log houses were low - up to 13 crowns. They were usually placed without a foundation or on low wooden posts. Many houses were made of adobe. Sometimes such houses were built using formwork - plank walls.

Roofs The roofs of dwellings were usually hipped and covered with thatch. The straw was often coated with clay, which protected it from being blown away by the wind and, to a certain extent, protected it from fires. In a number of areas, roofs were covered with marsh reeds. There are almost no carvings on the houses of the Samara Mordovians.

Roofs The roofs of dwellings were usually hipped and covered with thatch. The straw was often coated with clay, which protected it from being blown away by the wind and, to a certain extent, protected it from fires. In a number of areas, roofs were covered with marsh reeds. There are almost no carvings on the houses of the Samara Mordovians.

Internal layout The stove was located in one of the corners at the entrance. Moksha had a kershpel - a boardwalk in front of the stove 25-30 cm high from the floor. But it was much less common than among the Moksha population of the indigenous territory of residence.

Internal layout The stove was located in one of the corners at the entrance. Moksha had a kershpel - a boardwalk in front of the stove 25-30 cm high from the floor. But it was much less common than among the Moksha population of the indigenous territory of residence.

The estate The canopies that were directly adjacent to the residential hut were mostly planked, less often chopped; there were also wattle canopies with an earthen floor. The courtyard (pirf - m., kardaz - e.) was directly adjacent to the house and had the shape of a rectangle or square. Open courtyards were widespread. The complex of household premises included premises for livestock, storage of equipment and household property, buildings for threshing and drying bread. Baths were usually placed on the shore of a reservoir. And on the street opposite the windows they built semi-dugout-type basements. Valuable property was stored in them in case of fire: grain, clothing, etc.

The estate The canopies that were directly adjacent to the residential hut were mostly planked, less often chopped; there were also wattle canopies with an earthen floor. The courtyard (pirf - m., kardaz - e.) was directly adjacent to the house and had the shape of a rectangle or square. Open courtyards were widespread. The complex of household premises included premises for livestock, storage of equipment and household property, buildings for threshing and drying bread. Baths were usually placed on the shore of a reservoir. And on the street opposite the windows they built semi-dugout-type basements. Valuable property was stored in them in case of fire: grain, clothing, etc.

Anthropological characteristics The Chuvash have the greatest similarity with the mountain Mari. Among the northern Chuvash, the influence of Mongoloid components is noticeable. The population of the southern regions has Caucasian features and gravitates towards the Mordovians.

Anthropological characteristics The Chuvash have the greatest similarity with the mountain Mari. Among the northern Chuvash, the influence of Mongoloid components is noticeable. The population of the southern regions has Caucasian features and gravitates towards the Mordovians.

types of Chuvash settlements Villages and hamlets. In the northern and central regions of the republic, Chuvash villages consisted of okolotok - clusters of courtyards, separated from each other by a considerable distance. The neighborhoods had a complicated layout and clustered estates. The first Chuvash settlements of the Kama region, the Southern Urals and Samarskaya Luka were small villages with randomly scattered estates.

types of Chuvash settlements Villages and hamlets. In the northern and central regions of the republic, Chuvash villages consisted of okolotok - clusters of courtyards, separated from each other by a considerable distance. The neighborhoods had a complicated layout and clustered estates. The first Chuvash settlements of the Kama region, the Southern Urals and Samarskaya Luka were small villages with randomly scattered estates.

Dwelling of the Chuvash Kurnaya Izbakh Khura Purt until the end of the 19th century. The most archaic building now is the hut, which is used as a summer kitchen.

Dwelling of the Chuvash Kurnaya Izbakh Khura Purt until the end of the 19th century. The most archaic building now is the hut, which is used as a summer kitchen.

House of the Chuvash Nara, table, wooden blocks, helmet fart. Later, long benches and wooden beds appeared.

House of the Chuvash Nara, table, wooden blocks, helmet fart. Later, long benches and wooden beds appeared.

Construction technology Currently, the rural Chuvash population builds log and brick houses. As a rule, these are four- or five-walled. In the Volga regions, huts are made from pine logs, linden and other deciduous trees.

Construction technology Currently, the rural Chuvash population builds log and brick houses. As a rule, these are four- or five-walled. In the Volga regions, huts are made from pine logs, linden and other deciduous trees.

Gable roofs, with high gables, decorated with saw-cut carvings. There are also houses with a hipped or half-hipped roof. The window frames are decorated with carvings. Polychrome paint is used in architectural decoration; strict and straight lines predominate in the architecture.

Gable roofs, with high gables, decorated with saw-cut carvings. There are also houses with a hipped or half-hipped roof. The window frames are decorated with carvings. Polychrome paint is used in architectural decoration; strict and straight lines predominate in the architecture.

Homesteads Open courtyard Kilcarthy. The house and outbuildings are connected in an L-shape or U-shape. Many of the buildings on the estate have a traditional location. A cage or barn is attached to the entryway. More than half of Chuvash farms have a nukhrep cellar. For fire safety purposes, a munch bath is placed in the garden, vegetable garden or on the street.

Homesteads Open courtyard Kilcarthy. The house and outbuildings are connected in an L-shape or U-shape. Many of the buildings on the estate have a traditional location. A cage or barn is attached to the entryway. More than half of Chuvash farms have a nukhrep cellar. For fire safety purposes, a munch bath is placed in the garden, vegetable garden or on the street.

The Gate is Blind, a richly ornamented so-called Russian gate with a gable roof, mounted on three or four massive oak pillars.

The Gate is Blind, a richly ornamented so-called Russian gate with a gable roof, mounted on three or four massive oak pillars.

Volga-Ural Tatars Sub-ethnic groups: Kazan Tatars, Kasimov Tatars and Mishars, sub-confessional community of Kryashens (baptized Tatars) and Nagaibaks.

Volga-Ural Tatars Sub-ethnic groups: Kazan Tatars, Kasimov Tatars and Mishars, sub-confessional community of Kryashens (baptized Tatars) and Nagaibaks.

Types of settlements Urban and rural settlements. cumulus, nesting forms of settlement, disorderly planning, characterized by cramped buildings, unevenness and confusion of streets, often ending in unexpected dead ends

Types of settlements Urban and rural settlements. cumulus, nesting forms of settlement, disorderly planning, characterized by cramped buildings, unevenness and confusion of streets, often ending in unexpected dead ends

The nature of the layout of settlements Villages (auls) were mainly located along the river network; there were many of them near springs, highways, and lakes. Small settlements in the lowlands, on the slopes of the hills. In the forest-steppe and steppe areas, large villages spread out in breadth on flat terrain predominated

The nature of the layout of settlements Villages (auls) were mainly located along the river network; there were many of them near springs, highways, and lakes. Small settlements in the lowlands, on the slopes of the hills. In the forest-steppe and steppe areas, large villages spread out in breadth on flat terrain predominated

Aul In the center of the auls, the estates of wealthy peasants, clergy, and merchants were concentrated; a mosque, shops, shops, and public grain barns were also located here. In the residential area of the villages there were sometimes schools, industrial buildings, and fire sheds. On the outskirts of the village there were above-ground or semi-dugout bathhouses and mills. In forest areas, as a rule, the outskirts of villages were set aside for pastures, surrounded by a fence, and field gates (basu kapok) were placed at the ends of the streets.

Aul In the center of the auls, the estates of wealthy peasants, clergy, and merchants were concentrated; a mosque, shops, shops, and public grain barns were also located here. In the residential area of the villages there were sometimes schools, industrial buildings, and fire sheds. On the outskirts of the village there were above-ground or semi-dugout bathhouses and mills. In forest areas, as a rule, the outskirts of villages were set aside for pastures, surrounded by a fence, and field gates (basu kapok) were placed at the ends of the streets.

Construction technology The main construction material is wood. The timber construction technique predominated. The construction of residential buildings made of clay, brick, stone, adobe, and wattle was also noted. The huts were above ground or on foundations, basements

Construction technology The main construction material is wood. The timber construction technique predominated. The construction of residential buildings made of clay, brick, stone, adobe, and wattle was also noted. The huts were above ground or on foundations, basements

The house was dominated by a two-chamber type - a hut - a vestibule, in some places there were five-walled houses, huts with a porch. Three-chamber huts with communications (hut - canopy - hut). In forest areas, huts, connected through a vestibule to a cage, dwellings with a cruciform plan, “round” houses, cross-shaped houses with a semi-basement living floor, two-, and occasionally three-story, predominated. Wealthy peasants built their residential log houses on stone and brick storerooms and placed shops and shops on the lower floor.

The house was dominated by a two-chamber type - a hut - a vestibule, in some places there were five-walled houses, huts with a porch. Three-chamber huts with communications (hut - canopy - hut). In forest areas, huts, connected through a vestibule to a cage, dwellings with a cruciform plan, “round” houses, cross-shaped houses with a semi-basement living floor, two-, and occasionally three-story, predominated. Wealthy peasants built their residential log houses on stone and brick storerooms and placed shops and shops on the lower floor.

The internal layout is a free location of the stove at the entrance, a place of honor “tour” in the middle of the bunks (seke), placed along the front wall. Only among the Kryashen Tatars the “tour” was placed diagonally from the stove in the front corner. The area of the hut along the stove line was divided by a partition or curtain into women's - kitchen and men's - guest halves. The interior of the home is represented by long bunks, which were universal furniture: they rested, ate, and worked on them. In the northern areas, and especially among the Mishar Tatars, shortened bunks were used, combined with benches and tables. Locally used were potmar, konik, and in a number of areas polati, wide plank shelves fixed above the door or along the walls of the shelf on which bedding was stored (in the daytime they were folded on a chest or on a special stand placed on planks). Wooden beds, placed in the corner at the entrance, were also used for sleeping.

The internal layout is a free location of the stove at the entrance, a place of honor “tour” in the middle of the bunks (seke), placed along the front wall. Only among the Kryashen Tatars the “tour” was placed diagonally from the stove in the front corner. The area of the hut along the stove line was divided by a partition or curtain into women's - kitchen and men's - guest halves. The interior of the home is represented by long bunks, which were universal furniture: they rested, ate, and worked on them. In the northern areas, and especially among the Mishar Tatars, shortened bunks were used, combined with benches and tables. Locally used were potmar, konik, and in a number of areas polati, wide plank shelves fixed above the door or along the walls of the shelf on which bedding was stored (in the daytime they were folded on a chest or on a special stand placed on planks). Wooden beds, placed in the corner at the entrance, were also used for sleeping.

Roof The roof is a truss structure, gable, sometimes hipped. With a rafterless structure in forest areas, a male roof was used, and in the steppe, a rolling covering made of logs and poles was used. Territorial differences were also observed in the roofing material: in the forest zone, planks were sometimes used, shingles were sometimes used, in the forest-steppe zone - straw, bast, in the steppe zone - clay, reeds.

Roof The roof is a truss structure, gable, sometimes hipped. With a rafterless structure in forest areas, a male roof was used, and in the steppe, a rolling covering made of logs and poles was used. Territorial differences were also observed in the roofing material: in the forest zone, planks were sometimes used, shingles were sometimes used, in the forest-steppe zone - straw, bast, in the steppe zone - clay, reeds.

Tatar estate The estates were divided into two parts: the front, clean courtyard, where the dwelling, storage facilities, and livestock buildings were located, and the back - a vegetable garden with a threshing floor. Here there was a current, a barn-shish, a chaff barn, and sometimes a bathhouse. The oldest layout of the courtyard was chaotic, with residential and utility buildings located separately. The predominant plan is courtyards built up with grouped buildings in “U”-, “L”-shaped, single-row, double-row planning forms. The typical appearance of estates was to place the gate in the middle of the front line of the yard. One of the sides of the estate was occupied by housing, the other by storage (cage, barn, pantry), and in some villages of peripheral areas - by summer kitchen (alachyk).

Tatar estate The estates were divided into two parts: the front, clean courtyard, where the dwelling, storage facilities, and livestock buildings were located, and the back - a vegetable garden with a threshing floor. Here there was a current, a barn-shish, a chaff barn, and sometimes a bathhouse. The oldest layout of the courtyard was chaotic, with residential and utility buildings located separately. The predominant plan is courtyards built up with grouped buildings in “U”-, “L”-shaped, single-row, double-row planning forms. The typical appearance of estates was to place the gate in the middle of the front line of the yard. One of the sides of the estate was occupied by housing, the other by storage (cage, barn, pantry), and in some villages of peripheral areas - by summer kitchen (alachyk).

Types of settlements: villages, villages and settlements. A later type of settlement, which appeared in the 19th century due to the lack of land among peasants, should be considered settlements and farms.

Types of settlements: villages, villages and settlements. A later type of settlement, which appeared in the 19th century due to the lack of land among peasants, should be considered settlements and farms.

The nature of the settlement layout Russian villages are characterized by a street or linear layout: two orders of houses located in a straight (or almost straight) line, with a roadway between them.

The nature of the settlement layout Russian villages are characterized by a street or linear layout: two orders of houses located in a straight (or almost straight) line, with a roadway between them.

Izba The main type of residential building among the Russian population of the Samara region was a wooden log hut with an underground

Izba The main type of residential building among the Russian population of the Samara region was a wooden log hut with an underground

Layout of the hut The layout of the home in the past was characterized by a three-chamber division: hut-canopy-cage. At the beginning of the 20th century, the layout of houses began to change. Dwellings began to be built more often according to the following types: hut-canopy (four walls); hut-canopy-hut, five-walled building. The last type was a dwelling consisting of two log houses with one common wall. a large Russian stove at the entrance, its mouth facing the front wall of the house with windows. The direction to the side wall is borrowed from the local Volga peoples. Diagonally from the stove there was a front - red - corner, in which icons - images - were hung at a certain height, closer to the ceiling. There was a large table in the front corner, and wide benches along the walls. Near the stove, above the entrance, almost half of the hut was occupied by beds. The space behind the stove - the woman's corner - was fenced off with a curtain or wooden partition.

Layout of the hut The layout of the home in the past was characterized by a three-chamber division: hut-canopy-cage. At the beginning of the 20th century, the layout of houses began to change. Dwellings began to be built more often according to the following types: hut-canopy (four walls); hut-canopy-hut, five-walled building. The last type was a dwelling consisting of two log houses with one common wall. a large Russian stove at the entrance, its mouth facing the front wall of the house with windows. The direction to the side wall is borrowed from the local Volga peoples. Diagonally from the stove there was a front - red - corner, in which icons - images - were hung at a certain height, closer to the ceiling. There was a large table in the front corner, and wide benches along the walls. Near the stove, above the entrance, almost half of the hut was occupied by beds. The space behind the stove - the woman's corner - was fenced off with a curtain or wooden partition.

Construction technology The frame of such a dwelling was assembled from logs folded into quadrangular horizontal crowns and fastened in various ways: “in a cup” (in a corner), in a hood (with protruding ends), as well as in a hook, in an igloo, in an ohlup. The log house, consisting on average of 12 -15 crown logs, was placed on a foundation - chairs, which could be oak posts, rubble stone or limestone. The floor was laid on crossbars fastened at the level of the second or third crown. The grooves of the frame were lined with moss and tow, and the outside was coated with clay. At the same time, window and door openings were designed. Windows measuring 40 x 60 cm were cut out in 5-7 crowns and bordered with platbands, less often with shutters - closed. In the steppe zone, adobe was used instead of forest in Russian house-building. The walls of the residential hut were laid out from bricks made in special molds from a mixture of clay, straw and sand and dried in the sun. The cracks between the bricks were filled with liquid clay.

Construction technology The frame of such a dwelling was assembled from logs folded into quadrangular horizontal crowns and fastened in various ways: “in a cup” (in a corner), in a hood (with protruding ends), as well as in a hook, in an igloo, in an ohlup. The log house, consisting on average of 12 -15 crown logs, was placed on a foundation - chairs, which could be oak posts, rubble stone or limestone. The floor was laid on crossbars fastened at the level of the second or third crown. The grooves of the frame were lined with moss and tow, and the outside was coated with clay. At the same time, window and door openings were designed. Windows measuring 40 x 60 cm were cut out in 5-7 crowns and bordered with platbands, less often with shutters - closed. In the steppe zone, adobe was used instead of forest in Russian house-building. The walls of the residential hut were laid out from bricks made in special molds from a mixture of clay, straw and sand and dried in the sun. The cracks between the bricks were filled with liquid clay.

The estate The estate was fenced with a plank or wattle fence. Of the outbuildings, the most interesting are the mud hut (a summer kitchen, common in the southern steppe regions of the region) and the kalda (a pen for livestock). Baths were usually built near a water source, on the outskirts of the village. In the steppe regions of the region in the 19th century, in many villages they usually washed and steamed in a large Russian stove.

The estate The estate was fenced with a plank or wattle fence. Of the outbuildings, the most interesting are the mud hut (a summer kitchen, common in the southern steppe regions of the region) and the kalda (a pen for livestock). Baths were usually built near a water source, on the outskirts of the village. In the steppe regions of the region in the 19th century, in many villages they usually washed and steamed in a large Russian stove.

Layout of settlements Settlements were located along rivers and streams, along the banks of lakes, in ravines and ravines, near groves and forests, along large highways, in foothill valleys. Villages usually stretched out in one row or street. At the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries. street, street-block, street-radial, street-chaotic, street-nested, and row layouts of Ukrainian villages predominated.

Layout of settlements Settlements were located along rivers and streams, along the banks of lakes, in ravines and ravines, near groves and forests, along large highways, in foothill valleys. Villages usually stretched out in one row or street. At the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries. street, street-block, street-radial, street-chaotic, street-nested, and row layouts of Ukrainian villages predominated.

Construction technology Low, elongated whitewashed huts were built without a basement with an earthen or adobe floor. The walls were erected from various materials: wood, clay, stone. Due to the rise in prices for timber in the end. 19th - early 20th centuries Logging technology began to be combined with, and often replaced by, frame, adobe, adobe, and brick. In all areas, the ancient Ukrainian tradition of covering with clay and whitewashing log, frame and adobe walls was firmly preserved.

Construction technology Low, elongated whitewashed huts were built without a basement with an earthen or adobe floor. The walls were erected from various materials: wood, clay, stone. Due to the rise in prices for timber in the end. 19th - early 20th centuries Logging technology began to be combined with, and often replaced by, frame, adobe, adobe, and brick. In all areas, the ancient Ukrainian tradition of covering with clay and whitewashing log, frame and adobe walls was firmly preserved.

Layout of the hut The traditional layout of the house is two- and three-partition. A two-chamber house consisted of a “hut” and an unheated vestibule. In a three-chamber house, two huts or a hut and a cold “comora” were connected by a vestibule. Multi-room houses with a complicated layout were characteristic of urban-type settlements, large Ukrainian settlements with developed fishing activities, and Cossack villages. All Ukrainian settlers had an internal hut plan that was typical for Ukraine. In the back corner of the hut there was an oven, widely known as a Russian oven with the mouth facing the long side wall of the house. Diagonally from the stove there is the front corner (“pokut”), where icons hung and there was a dining table, along the front and side walls there are benches (“lavi”) reinforced into the walls, opposite the mouth of the stove closer to the door is the kitchen half. The oven, and sometimes the pocket and the front wall, were painted with multi-colored clay, blue, paints; the front corner was decorated with towels, artificial and fresh flowers, ears of rye and wheat.

Layout of the hut The traditional layout of the house is two- and three-partition. A two-chamber house consisted of a “hut” and an unheated vestibule. In a three-chamber house, two huts or a hut and a cold “comora” were connected by a vestibule. Multi-room houses with a complicated layout were characteristic of urban-type settlements, large Ukrainian settlements with developed fishing activities, and Cossack villages. All Ukrainian settlers had an internal hut plan that was typical for Ukraine. In the back corner of the hut there was an oven, widely known as a Russian oven with the mouth facing the long side wall of the house. Diagonally from the stove there is the front corner (“pokut”), where icons hung and there was a dining table, along the front and side walls there are benches (“lavi”) reinforced into the walls, opposite the mouth of the stove closer to the door is the kitchen half. The oven, and sometimes the pocket and the front wall, were painted with multi-colored clay, blue, paints; the front corner was decorated with towels, artificial and fresh flowers, ears of rye and wheat.

Ukrainian estate Ukrainian settlers tried to orient most of the windows to the sunny side; the house was placed somewhat back from the fence, where the front garden was laid out. The predominant type of yard is open, with freely arranged household items. buildings They were separated from the street and from the neighboring estate by a fence made of wattle fence, palisade, poles or boards. Closer to the house and to the street, “cleaner” buildings were grouped - a barn or comora, a barn and sheds for farming. -X. inventory, summer kitchen, cellar, storage rooms. In the depths of the yard they built sheds for cows, stables, sheds for sheep, sheds and open pens for livestock. The Ukrainian estate ended with a fairly large vegetable garden, where a significant area was allocated for a garden and “livada” (meadow) with willow and acacia plantings used for home construction. Behind the garden or at the end of it there was a threshing floor for threshing bread and a shed (“klunya”) for storing bread in sheaves, threshing and drying it.

Ukrainian estate Ukrainian settlers tried to orient most of the windows to the sunny side; the house was placed somewhat back from the fence, where the front garden was laid out. The predominant type of yard is open, with freely arranged household items. buildings They were separated from the street and from the neighboring estate by a fence made of wattle fence, palisade, poles or boards. Closer to the house and to the street, “cleaner” buildings were grouped - a barn or comora, a barn and sheds for farming. -X. inventory, summer kitchen, cellar, storage rooms. In the depths of the yard they built sheds for cows, stables, sheds for sheep, sheds and open pens for livestock. The Ukrainian estate ended with a fairly large vegetable garden, where a significant area was allocated for a garden and “livada” (meadow) with willow and acacia plantings used for home construction. Behind the garden or at the end of it there was a threshing floor for threshing bread and a shed (“klunya”) for storing bread in sheaves, threshing and drying it.

As a manuscript

Medvedev Vladislav Valentinovich

SETTLEMENTS AND HOUSINGS OF CHUVASH BASHKORTOSTAN

SECOND HALF OF THE XIX – BEGINNING OF THE XX CENTURY

Specialty 07.00.07 – Ethnography, ethnology, anthropology

dissertations for an academic degree

candidate of historical sciences

Izhevsk – 2012

The work was carried out at the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Magnitogorsk State University"

Scientific director: Candidate of Historical Sciences Atnagulov Irek Ravilevich

Official opponents: Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Shutova Nadezhda Ivanovna Candidate of Historical Sciences Matveev Georgy Borisovich

Leading organization: Institute of Ethnological Research of the Ufa Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The defense will take place on February 28, 2012 at 13.00 at a meeting of the dissertation council DM 212.275.01 at the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Udmurt State University" at the address: 426034, Izhevsk, st.

Universitetskaya, 1, bldg. 2, room. _

Scientific secretary of the dissertation council, candidate of historical sciences, associate professor G.N. Zhuravleva

GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF WORK

Relevance research. Settlements and dwellings are an integral part of the material culture of an ethnic group. Along with the food system and traditional costume, the organization of living space is the leading one in the life support structure of the people. Rural settlements can be considered as a set of peasant estates, united into a whole community and interconnected by various relationships: family ties, common economic activities, joint land use and ownership of forest lands, hay meadows, and water resources.The study of the formation of various types of settlements - villages, hamlets, hamlets and other points - helps to create a clear picture of understanding the socio-economic situation of the Chuvash peasantry in the second half of the 19th - early 20th centuries. in Bashkiria. In the process of considering the history of the emergence of settlements, the reasons, the course of migration, the ethnic composition of new settlements, and economic activities are revealed.

The central component of the peasant household was the residential complex.

Its location in relation to the outside world, relative to outbuildings, building materials and structures, construction techniques - all these parameters deserve careful study and analysis.

Nowadays, the appearance of settlements is changing. Traditional buildings and dwellings are being destroyed and their complete disappearance is soon possible.

This fact actualizes the need for collecting and theoretically understanding information about the dwellings and economic buildings of the Chuvash people of Bashkortostan.

The object of the study is a group of Chuvash living on the territory of Bashkiria, the subject is rural settlements, buildings and dwellings of the Chuvash of Bashkortostan.

The chronological scope of the study is limited to the second half of the 19th – early 20th centuries, although many aspects are covered in a longer historical retrospective. For comparison, materials of more recent origin are also used. The lower time limit is the second half of the 19th century. – determined by the fact that in this period, in connection with the reform of 1861, migrations of peasants from European Russia to free lands, including Bashkiria, are intensifying. The development of infrastructure, trade, and the stratification of the peasantry led to significant changes in the appearance of settlements, affecting, among other things, traditional architecture.

The upper limit can be considered the beginning of the 20th century, when the process of migration of the Chuvash to Bashkiria was completed and elements of ethnic culture functioned among the population, for example, buildings, dwellings, which soon underwent transformation and then partial disappearance.

The territorial scope of the study is defined within the natural geographical boundaries of the eastern part of the Russian Plain - the Urals, the Southern Urals, the Trans-Urals - covering the territory of modern Bashkiria.

Historically, the Chuvash settled within the western, southwestern, central and southern regions of modern Bashkiria. The study pays special attention to the Chuvash settlements of the Southern zone, as the least studied. Modern Chuvash villages in the south of Bashkiria are localized in Zilairsky, Zianchurinsky, Kugarchinsky, Kuyurgazinsky, Meleuzovsky and Khaibullinsky districts.

Degree of knowledge Problems. Quite a lot of scientific works devoted to the settlements, dwellings and outbuildings of the Chuvash have been published. However, the majority of them belong to the population of the metropolis, while the Chuvash of various ethno-territorial groups have still not been fully studied. In this regard, the presented historiographical review will reflect works related to the Chuvash of Bashkiria and containing direct or indirect information about this group.

According to the generally accepted gradation in the historiography of the problem, three chronological periods are distinguished: pre-revolutionary, Soviet, post-Soviet.

1. Pre-revolutionary period. The first written work in which there is a mention of the Chuvash on the Bashkir lands is the work of P.I.

Rychkova1. It contains materials about the settlement of the Chuvash in different provinces, issues of religion and social status are covered, but there is no description of material culture and life. In his travel notes he reflected what he saw among the Chuvash and P.S. Pallas2. His work is a historical and ethnographic description of various aspects of the material and spiritual culture of the people, including the farmstead, the residential hut, and its interior. Materials on the ethnography of the Chuvash and peoples living nearby were systematized by G.F.

Separate paragraphs are devoted to the structure of villages, estates, and housing.

In the work of I.G. Georgi devoted an insignificant paragraph to the Chuvash, however, it mentions their settlement in the Orenburg province and describes significant elements of culture4. A comprehensive work dedicated to the Chuvash can be considered “Notes of Alexandra Fuks about the Chuvash and Cheremis of the Kazan province”5. Despite the fact that the object of the author’s scientific attention was the Chuvash of the Kazan province, the collected materials create a single image of the ethnic group, including settlers on the Bashkir lands.

By the middle of the 19th century. refers to the work of V.M. Cheremshansky, dedicated to Rychkov P.I. Topography of the Orenburg province. Orenburg: Printing house of B. Breolin, 1887. Part 1. P. 133 Pallas P.S. Traveling through different provinces of the Russian Empire. St. Petersburg, 1773. Part 1.

Miller G.F. Description of the pagan peoples living in the Kazan province, such as the Cheremis, Chuvash and Votyaks. St. Petersburg, 1791.

Georgi I.G. Description of all the peoples living in the Russian state: their everyday rituals, customs, clothes, homes, exercises, fun, religions and other attractions. SPb.:

Russian Symphony, 2005. pp. 80-85.

Fuks A.A. Notes of Alexandra Fuks about the Chuvash and Cheremis of the Kazan province. Kazan: Printing house of the Kazan Imperial University, 1840.

description of the Orenburg province and the peoples living within its borders6. In the chapter “Turkish-Tatar Tribe,” the author, together with the Bashkirs, Teptyars, Meshcheryaks, and Tatars, examines the Chuvash. Their anthropological characteristics are given, their way of life, religious specifics, holidays and rituals are described.

In custody the dwelling, food system and costume of the Chuvash are outlined.

Works containing general materials about the Chuvash, primarily the Kazan province, include the works of A.F. Rittikha7, V.K. Magnitsky8, K.S.

Milkovich9. At the beginning of the 20th century. publications of S.A. were published Bagina10, S.I. Rudenko11.

The work of G.I. deserves attention. Komissarov “Chuvash of the Kazan Trans-Volga Region”12. Having described the culture of the Chuvash in the Kazan province, he touches on the problem of their settlement in the Urals and Siberia. The researcher presents a detailed analysis of settlements and dwellings in a separate chapter. He examined the structure of villages, estates, outbuildings, dwellings, and interiors.

In general, studies of the pre-revolutionary period are works of a generalizing nature. They examine not only the Chuvash, but also the peoples neighboring them, the features of their material and spiritual culture, and provide the first information about the emergence and types of settlements, the location of estates, household buildings, and residential complexes.

Along with the general works of P.S. Pallas, G.F. Miller and other authors, works devoted only to the Chuvash appear (K.S. Milkovich, V.A.

Sboev, V.K. Magnitsky, G.I. Komissarov, etc.).

2. Soviet period. The study of the Chuvash of Bashkortostan in this chronological period can be systematized as follows:

1. 1917–1930 – the time of functioning of elements of traditional culture in everyday life, a high degree of preservation of folk architecture, which was recorded during expeditionary trips. Changes in ethnic culture are evident by the beginning of 1930;

2. 1930–1955 – the period of the organization of new types of common economy, the NEP, the events of the Great Patriotic War led to a weakening of interest in the history and ethnography of the peoples of the Ural-Volga region.

Cheremshansky V.M. Description of the Orenburg province in economic-statistical, ethnographic and industrial relations. Ufa: Printing house of the Orenburg Provincial Board, 1859. pp. 173-178.

Rittich A.F. Materials for the ethnography of Russia. XIV. Kazan province. Kazan: Printing house of the Imperial Kazan University, 1870. Part II. pp. 41-120.

Magnitsky V.K. Materials for the explanation of the old Chuvash faith. Kazan: Printing house of the Imperial University, 1881.

Milkovich K.S. About the Chuvash. Ethnographic essay by an unknown author of the 18th century. Kazan:

Printing house of the provincial government, 1888.

Bagin S.A. About the fall away to Mohammedanism of the baptized foreigners of the Kazan diocese and about the reasons for this sad phenomenon // Orthodox interlocutor. Kazan, 1910. No.1. pp. 118-127; No. 2. pp. 225-236.

Rudenko S.I. Chuvash gravestones // Materials on the ethnography of Russia. St. Petersburg, 1910. T. 1. S.

Komissarov G.I. Chuvash of the Kazan Trans-Volga region // News of the Society of Archeology, History and Ethnography at the Imperial Kazan University. Kazan: Typo-lithography of the Imperial University, 1911. T.

XXVII. Vol. 5. pp. 311-432.

3. 1955–1991 – conducting expeditions in Bashkiria to study the local group of Chuvash, expanding the scope of the survey and applying the principle of “continuous” study.

From the works of researchers 1917–1930. the most significant works of N.V.

Nikolsky13. His research was based on materials he collected among the Chuvash of the metropolis, but contained valuable information about the Chuvash of Bashkiria. P.A. Petrov-Turinge conducted expeditions to study this group. Its results were published in several publications, among which the article “Work among the Chuvash”14 is of interest. The author summarized the results of field work in various Chuvash settlements. During the expedition, 1,200 plans of dwellings and courtyards were recorded, materials on public education were collected, about Chuvash songs were recorded, and 200 photographs were taken.

The work of A.P. belongs to the second period. Smirnova “Ancient history of the Chuvash people (before the Mongol conquest)”15. The work provides a description of dugouts, half-dugouts that existed in Chuvashia in the Middle Ages, and later among Chuvash migrants.

In 1955–1991, quite a lot of works were published, including studies by N.I. Vorobyov16, collective monograph “Chuvash” in 2 parts, dedicated to the material and spiritual culture of the Chuvash, including local ethnic groups17. Works that contain information on the history of the Chuvash peasantry and the development of relations in the village include the works of I.D. Kuznetsova18, V.D. Dimitrieva19.

The process of peasant migrations to Bashkiria and the participation of the Chuvash in them was considered by A.N. Usmanov20. Somewhat later, these same questions were raised in the studies of W.Kh. Rakhmatullin21 and S.Kh. Alishev22, touching on the problem of the entry of the peoples of the Volga region into the Russian state and their subsequent socio-economic development.

Chuvash folk art - weaving, embroidery, wood carving Nikolsky N.V. A short course on the ethnography of the Chuvash. Cheboksary: Chuvash. state publishing house, 1928. Issue. 1.

Petrov-Turinge P.A. Work among the Chuvash // Materials of the Society for the Study of Bashkiria: Collection of Local History. Ufa: Publishing House of the Society for the Study of Bashkiria, 1930. No. 3-4. pp. 95-98.

Smirnov A.P. Ancient history of the Chuvash people (before the Mongol invasion). Cheboksary:

Chuvashgosizdat, 1948.

Vorobiev N.I. On the history of rural housing among the peoples of the Middle Volga region // Brief communications of the Institute of Ethnography named after. N.N. Miklouho-Maclay. M.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1956 P. 3-18; Vorobiev N.I. Wood carving among the Chuvash // Soviet ethnography. M.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1956. No. 4. WITH.

Chuvash. Ethnographic research. Material culture. Cheboksary: Chuvash. state publishing house, 1956. Ch.

1.; Chuvash. Ethnographic research. Spiritual culture. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 1970. Part 2.

Kuznetsov I.D. Essays on the history of the Chuvash peasantry. Cheboksary: Chuvash. state publishing house, 1957;

Kuznetsov I.D. Peasantry of Chuvashia during the period of capitalism. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 1963.

Dimitriev V.D. History of Chuvashia in the 18th century. Cheboksary: Chuvash. state publishing house, 1959.

Usmanov A.N. Annexation of Bashkiria to the Russian state. Ufa: Kitap, 1960.

Rakhmatullin U.Kh. Population of Bashkiria in the 17th – 18th centuries. Issues of formation of the non-Bashkir population. M.: Nauka, 1988.

Alishev S.Kh. Historical destinies of the peoples of the Middle Volga region in the 16th – early 19th centuries. M.: Nauka, 1990.

etc. – studied by G.A. Nikitin and T.A. Kryukova23. They examined different carving techniques, patterns of ornamentation, and analyzed fragments of the house that were covered with patterns. The article by L.A. deserves special attention. Ivanov, in which the settlements and dwellings of the Chuvash of the Kama region and the Southern Urals are subjected to a comprehensive study24. Later, the materials of the article were used by the author in his monograph “Modern life and culture of the Chuvash population”25.

The first study devoted to one of the main domestic buildings - the bathhouse - was an article by G.A. Alekseeva26. The structure of villages and hamlets was studied by A.G. Simonov27. Settlements and dwellings of the Chuvash, as well as other peoples of the Volga region, were studied by K.I. Kozlova28. The collective monograph “Peoples of the Volga and Urals: Historical and Ethnographic Essays” also examined Chuvash villages, residential and economic complexes29.

In the works of G.B. Matveev, construction equipment, housing structures, household buildings, and materials were studied and analyzed in detail30.

Among the works devoted to the decorative design of a home, the most significant is the work of E.P. Busygina, N.V. Zorina and L.S. Toksubaeva31. They consider methods and techniques for decorating a house, the design of jewelry, types of carvings, and analyze the architecture of the peoples of the Volga region.

Transformation of material culture in the 20th century. was reflected in the article by V.P. Ivanova “Ethnocultural processes among the Cis-Ural Chuvash (based on materials from the 1987 expedition)”32.

The collective work of the employees of the ChNII YaLIE “Chuvashi Nikitin G.A., Kryukova T.A.” is interesting. Chuvash folk art. Cheboksary: Chuvash. state

publishing house, 1960.

Ivanov L.A. Settlements and dwellings of the Chuvash population of the Kama Trans-Volga region and the Southern Urals // Questions of the history of Chuvashia. Scientific notes. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 1965. Issue. XXIX. pp. 184-211.

Ivanov L.A. Modern life and culture of the rural Chuvash population. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book Publishing house, 1973.

Alekseev G.A. On the use of baths in Chuvash folk medicine // Questions of the history of the Chuvash Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Scientific notes. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1970. Vol. 52. pp. 284-289.

Simonov A.G. Cumulus plan in the development of villages of the peoples of the Middle Volga region // Ancient and modern ethnocultural processes in the Mari region. Yoshkar-Ola: MarNII, 1976. pp. 134-144.

Kozlova K.I. Ethnography of the peoples of the Volga region. M.: Moscow University Publishing House, 1964.

Peoples of the Volga and Urals regions. Historical and ethnographic essays. M.: Nauka, 1985. pp. 175-199.

Matveev G.B. Peasant construction equipment (Northwestern regions of Chuvashia) // Questions of material and spiritual culture of the Chuvash people. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1986. P. 31-44; Matveev G.B. On some features of the traditional dwelling of the Chuvash population of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Ulyanovsk and Kuibyshev regions // Culture and life of the lower Chuvash. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1986. P. 32-47; Matveev G.B. Rural settlements of the Chuvash in the second half of the 19th – early 20th centuries.

(Materials for the historical and ethnographic atlas) // Ethnography of the Chuvash peasantry. Cheboksary:

CHNII YALIE, 1987. P. 35-50; Matveev G.B. Dwelling and outbuildings of the middle Chuvash (Second half of the 19th – early 20th centuries) (Materials for the historical and ethnographic atlas) // Traditional economy and culture of the Chuvash. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1988. pp. 53-63.

Busygin E.P., Zorin N.V., Toksubaeva L.S. Decorative design of rural housing in the Kazan Volga region. Kazan: Tatar book. publishing house, 1986.

Ivanov V.P. Ethnocultural processes among the Cis-Ural Chuvash (based on materials from the 1987 expedition) // Ethnos and its divisions. Ethnic and ethnographic groups in the Volga-Ural region. M.: Nauka, 1992. Part 2. pp. 70-79.

Cis-Urals: cultural and everyday processes”33, which touches on the formation of the Chuvash group of Bashkortostan, material and spiritual culture, including art using the example of grave structures and decorative design of homes34.

So, during the Soviet period, the local group of Chuvash in Bashkortostan became the subject of independent study. In the works of researchers, issues of migration to the Bashkir lands, the development of villages in new conditions, interethnic contacts, the process of transformation of ethnic culture, change and partial conservation of elements are discussed.

3. Post-Soviet period. Due to the increasing interest in the problem of the ethnographic specificity of local groups of the Chuvash of the Ural-Volga region and more distant territories, scientists are paying more attention to the study of the Chuvash of Bashkortostan.

The history of the emergence of Chuvash settlements on the territory of Bashkiria was examined in detail by A.Z. Asfandiyarov 35. The author also touches on the problem of interethnic relations in Bashkiria, the situation of immigrants, and issues of land ownership by the newcomer population36. V.P. Ivanov devoted his works to the analysis of settlement, interethnic contacts, and population dynamics of the Chuvash37. V.D. studied the progress of Chuvash migration to the Urals and other areas. Dimitriev38, based on historical legends.

Religious ideas, the preservation of traditional beliefs, the semantics of housing among the Chuvash of the metropolis and various local groups were analyzed in the works of A.K. Salmina39. Turning to ritual actions, he also cites the areas of their existence. The content contains the Chuvash of the Urals: cultural and everyday processes. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1989.

Trofimov A.A. Folk and amateur art // Chuvash of the Urals: cultural and everyday processes. Cheboksary: CHNII YALIE, 1989. pp. 72-93.

Asfandiyarov A.Z. History of villages and hamlets of Bashkortostan. Reference book. Ufa: Kitap, 1990. Book. 1;

Asfandiyarov A.Z. History of villages and hamlets of Bashkortostan. Reference book. Ufa: Kitap, 1998. Book. 2-3;

Asfandiyarov A.Z. History of villages and hamlets of Bashkortostan. Reference book. Ufa: Kitap, 1993. Book. 3.

Asfandiyarov A.Z. Bashkiria after joining Russia (second half of the 16th – first half of the 19th century). Ufa: Kitap, 2006.

Ivanov V.P. Settlement and number of Chuvash: Ethnogeographical sketch. Cheboksary, 1992; Ivanov V.P. Chuvash ethnic group. Problems of history and ethnogeography. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 1998; Ivanov V.P.

Formation of the Chuvash diaspora // Races and peoples: Modern ethnic and racial problems. M.:

Science, 2003. Vol. 29. P. 105-123; Ivanov V.P. Settlement and number of Chuvash in Russia: historical dynamics and regional features (Historical and ethnographic research): Dis... doc. ist. Sci.

Cheboksary, 2005; Ivanov V.P. Ethnic geography of the Chuvash people. Historical population dynamics and regional features of settlement. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 2005; Ivanov V.P., Mikhailov Yu.T. Chuvash population of the Orenburg region: formation of an ethno-territorial group:

ethnoculture, population dynamics // Chuvash Humanitarian Bulletin. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 2007/2008.

No. 3. pp. 63-79.

Dimitriev V.D. Chuvash historical legends: Essays on the history of the Chuvash people from ancient times to the mid-19th century. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 1993.

Salmin A.K. Religious and ritual system of the Chuvash. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 1993; Salmin A.K. Chuvash folk rituals. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 1994; Salmin A.K. Semantics at home among the Chuvash. Cheboksary:

ChGIGN, 1998; Salmin A.K. Three Chuvash deities. Cheboksary: Krona, 2003; Salmin A.K. The Chuvash religion system. St. Petersburg: Nauka, 2007.

A significant contribution to the study of the group was made by the work of ethnographer I.G.

Petrova “Chuvash of Bashkortostan (Popular essay on ethnic history and traditional culture)”40. The publication has become a comprehensive study containing a brief description of the material and spiritual culture of the Chuvash in Bashkiria. It, among other things, examined the estate, outbuildings, housing, and interior. The results were published in a number of publications41. In the post-Soviet period, G.B. continues research.

Matveev42. A significant proportion of his works are devoted to the Chuvash dwelling and yard (materials, structures, location of buildings, etc.).

The problems of resettlement of the Chuvash, Islamization in connection with foreign ethnic influence, changes and the degree of preservation of elements of folk culture, language processes were considered by E.A. Yagafova43.

An article by researcher P.P. is also important when studying housing. Fokina “Building rituals of a modern Chuvash family”44. D.F.

Madurov in his work deals with the issues of decorating the home, estate and outbuildings of the Chuvash45.

The resettlement of the Chuvash to Bashkiria becomes the subject of research by G.A. Nikolaeva46. The most detailed coverage of the problem is offered by I.V. Sukhareva47. First chapter her work is devoted to the migration of the Chuvash in the 17th – 19th centuries. Petrov I.G. contributed to the study of the Chuvash villages of Bashkiria. Chuvash of Bashkortostan (Popular essay on ethnic history and traditional culture).

Ufa: Ufa City Printing House, 1994.

Petrov I.G. Chuvash // Vatandash. Ufa: Kitap, 1999. No. 9. pp. 148-168.

Matveev G.B. Material culture of the Chuvash. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 1995; Matveev G.B. Dwelling and outbuildings of the Chuvash of the Urals // Materials on the ethnography and anthropology of the Chuvash.

Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 1997. pp. 118-130; Matveev G.B. Chuvash folk architecture: from antiquity to modern times. Cheboksary: Chuvash. book publishing house, 2005; Matveev G.B. The evolution of Chuvash folk architecture in the 1920s // Artistic culture of Chuvashia: 20s of the XX century. Cheboksary: ChGIGN, 2005.

Yagafova E.A. Formation of ethno-territorial groups of the Chuvash in the 17th – 19th centuries (historical and cultural aspect) // Races and peoples: Modern ethnic and racial problems. M.: Nauka, 2003. Vol.

29. pp. 124-148; Yagafova E.A. Islamization of the Chuvash in the Ural-Volga region in the 18th – early 20th centuries. // Ethnographic review. M.: Nauka, 2007. No. 4. pp. 101-117; Yagafova E.A. Chuvash of the Ural-Volga region: