Why does the actor reproduce so diligently? Captain Jack Sparrow as an ideal consumer

Literature lesson

« The image of a man in F. Schiller’s ballad “The Glove”

(translated by V. A. Zhukovsky)"

(6th grade).

Lesson type: learning new material.

View: teacher's story, conversation.

Lesson objectives:

Educational: develop the ability to determine the theme and idea of a work; characterize the characters, briefly retell the episodes; repeat knowledge of literary theory.

Educational: develop students’ mental activity, the ability to analyze, find key episodes and words in the text; draw conclusions, compare, generalize; improve students’ oral speech, contribute to the formation of artistic taste.

Educational: enrich the moral experience of students ; to create a need to discuss such moral problems as the problem of human dignity, the value of life and true feelings.

Aesthetic: to develop the ability to see the skill of a writer.

Technologies:student-centered learning, problem-based learning.

During the classes:

1. Organizational moment.

2. Updating knowledge (survey on the material covered):

1) What do you know about the ballad as a literary genre?

2) What types of ballads are there based on the theme?

3) What artistic features of a ballad can you name?

3. Teacher reading F. Schiller’s ballad “The Glove.”

4. Theoretical question: prove that this is a ballad (there is a plot, because it can be retold; an extraordinary incident; the intense nature of the narrative; dialogue between characters; the time of action is knightly times).

5. Working with the content of the ballad.

What kind of battle do King Francis and his retinue expect, sitting on a high balcony? (Battle of the animals.)

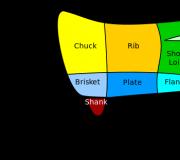

What animals should take part in this battle? (A shaggy lion, a brave tiger, two leopards.)

How do we usually imagine these animals? (Predatory, ferocious, cruel.)

Problematic question № 1: How does the author show them? (Lazy, calm, if not friendly.)Why?

We come to a contrast between the images of predators and people. The image of a beauty who drops her glove into the arena. The author's methods and techniques for creating an image (epithets, opposition (love is a glove, its desire is the behavior of animals), the character's speech).

We come to the conclusion that the heartlessness and pride of the beauty (the lady of the heart of the knight Delorge) is worse than the bloodthirsty cruelty of wild animals.

6. The image of the main character of the ballad - knight Delorge.

Are animals really that harmless? (Prove from the text. The author conveys the mortal danger that Delorge is exposed to indirectly: through the reaction of the audience (“Knights and ladies with such audacity, their hearts were clouded with fear...”)

How is the knight shown in this episode? The author's ways and techniques of creating an image (vocabulary (knight), epithets, contrast (his courage - the reaction of the audience)).

Problematic question: What did we expect at the end of the poem? Probably, like in Hollywood films, a happy ending: the beauty understands what a wonderful person loves her, repents of her cruelty and pride, and... they lived happily ever after...

Problematic question No. 2: For us, readers, the last three lines are completely unexpected (“But, coldly accepting the greeting of her eyes, He threw his glove in her face and said: “I don’t demand a reward.”) Explain the behavior of the knight Delorge. To do this, you need to try to put yourself in his place. .

We come to understand the knight’s action: he refuses love from a heartless beauty who does not value him, his life, and therefore does not love him.

7. Question about the meaning of the title. What does glove mean?

Possible answers:

- the pride of a beauty, a symbol of the pettiness of her soul;

- devotion and love of a knight;

- an occasion to talk about something very important for every person: self-esteem, the value of human life, true love.

So what is this ballad about?

This work is about the price of human life. Medieval knights risked and died for the sake of their king, the church or the Beautiful Lady. They died in crusades and bloody wars. Human life was inexpensive in those days. Schiller tells the legend about the knight Delorge and his lady so that the reader understands: you cannot play with death, pay someone else's life for the sake of personal whim. Love for a person is, first of all, the desire to see him alive, healthy and happy.

8. Conclusion: You must always think about how your behavior will affect another person. Doesn't it threaten the life of your friend, neighbor? We must take care of each other’s lives, then the world around us will be safe for everyone. Life is the greatest value on earth!

Schiller was born into the family of a regimental doctor. As a child, he was sent to a closed educational institution - the Military Academy, founded by the Duke of Württemberg. The purpose of the Academy was to educate obedient servants to the throne. Schiller spent many years on this “slave plantation.” From here he endured a burning hatred of despotism and a love of freedom. After graduating from the Academy, where he studied medicine, Schiller was forced to accept a position as a doctor in a military garrison, but did not give up his dream of devoting himself to literature.

The play “The Robbers,” written at the Academy, was accepted for production in the then famous Mannheim Theater in 1782. Schiller really wanted to attend the premiere of his play, but he knew in advance that he would be denied leave, and therefore secretly went to Mannheim, which was not subject to the Duke of Württemberg. For violating the garrison service regulations, Schiller served two weeks in prison. Here he made his final decision regarding his future fate. On an autumn night in 1782, he secretly leaves the duchy, never to return there again. From this time on, years of wandering, deprivation, and need begin, but at the same time, years filled with persistent literary work. In the early period of his work, Schiller created works filled with protest against arbitrariness and tyranny.

In the summer of 1799, the writer’s wanderings ended: he moved permanently to Weimar, which became the largest cultural center in Germany. In Weimar, Schiller intensively studied history, philosophy, aesthetics, replenishing the knowledge that he felt he lacked. Over time, Schiller became one of the most educated people of his era and for a long time even taught history at one of the largest German universities.

Schiller left a rich creative heritage. These are lyrical and philosophical poems, and ballads, which were especially highly valued by Pushkin and Lermontov. But, of course, the most important work of his life was drama. The early dramas “The Robbers” and “Cunning and Love” (1784) immediately won the love of the audience. And the historical dramas “Don Carlos” (1787), “Mary Stuart” (1801), “The Maid of Orleans” (1801), “William Tell” (1804) brought him European fame.

Schiller called the ballad “The Glove” a story because it was written not in ballad form, but in the form of a narrative. Zhukovsky included it among the stories; the critic V. G. Belinsky had no doubt that it was a ballad.

“The Glove” was translated by Lermontov in 1829 (published in 1860), and by Zhukovsky in 1831.

Glove

Translation by M. Lermontov

The nobles stood in a crowd

And they waited silently for the spectacle;

Sitting between them

The king is majestically on the throne:

All around on the high balcony

The beautiful choir of ladies sparkled.

Here they heed the royal sign.

The creaky door opens,

And the lion comes out of the steppe

Heavy foot.

And suddenly silently

Looks around.

Yawning lazily

Shaking his yellow mane

And, having looked at everyone,

The lion lies down.

And the king waved again,

And the tiger is harsh

With a wild leap

The dangerous one took off,

And, having met a lion,

Howled terribly;

He beats his tail

After

Quietly he goes around the owner,

The bloody eyes do not move...

But a slave is before his master

Grumbles and gets angry in vain

And involuntarily lies down

He's next to him.

Then fall from above

Glove from a beautiful hand

Fate by a random game

Between a hostile couple.

And suddenly turning to his knight,

Cunegonde said, laughing slyly:

“Knight, I love to torture hearts.

If your love is so strong,

As you tell me every hour,

Then lift up my glove!”

And the knight runs from the balcony in a minute

And he boldly enters the circle,

He looks at the glove of me than wild animals

And he raises his bold hand.

-

_________

And the spectators are around in timid anticipation,

Trembling, they look at the young man in silence.

But now he brings the glove back,

And a gentle, flaming look -

- A pledge of short-term happiness -

He meets the hero with the girl's hand.

But burning with cruel annoyance,

He threw the glove in her face:

“I don’t need your gratitude!” -

And he immediately left the proud one.

Glove

Translation by V. Zhukovsky

In front of your menagerie,

With the barons, with the crown prince,

King Francis was seated;

From a high balcony he looked

In the field, awaiting battle;

Behind the king, enchanting

Blooming beauty look,

There was a magnificent row of court ladies.

The king gave a sign with his hand -

The door opened with a knock:

And a formidable beast

With a huge head

Shaggy lion

It turns out

He rolls his eyes around sullenly;

And so, having looked at everything,

Wrinkled his forehead with a proud posture,

He moved his thick mane,

And he stretched and yawned,

And he lay down. The king waved his hand again -

The shutter of the iron door banged,

And the brave tiger jumped out from behind bars;

But he sees a lion, becomes shy and roars,

He hits himself in the ribs with his tail,

"Glove". Artist B. Dekhterev

And sneaks, glancing sideways,

And licks the face with his tongue.

And, having walked around the lion,

He growls and lies down next to him.

And for the third time the king waved his hand -

Two leopards as a friendly couple

In one leap we found ourselves above the tiger;

But he gave them a blow with a heavy paw,

And the lion stood up roaring...

They resigned themselves

Baring their teeth, they walked away,

And they growled and lay down.

And the guests are waiting for the battle to begin.

Suddenly a woman fell from the balcony

The glove... everyone is watching it...

She fell among the animals.

Then on the knight Delorge with the hypocritical

And he looks with a caustic smile

His beauty says:

"When me, my faithful knight,

You love the way you say

You will return the glove to me."

Delorge, without answering a word,

He goes to the animals

He boldly takes the glove

And returns to the meeting again,

The knights and ladies have such audacity

My heart was clouded with fear;

And the knight is young,

As if nothing happened to him

Calmly ascends to the balcony;

He was greeted with applause;

He is greeted by beautiful glances...

But, having coldly accepted the greetings of her eyes,

A glove in her face

He quit and said: “I don’t demand a reward.”

Thinking about what we read

- So, before you is Schiller’s ballad “The Glove”. We invite you to read and compare two translations made by V. Zhukovsky and M. Lermontov. Which translation is easier to read? Which of them reveals the characters' characters more clearly?

- What did the beauty want? Why is the knight so offended by her?

- As we can see, the genre of this work was defined in different ways. What would you call “The Glove” - a ballad, a story, a short story? Repeat the definitions of these genres in the dictionary of literary terms.

Learning to read expressively

Prepare an expressive reading of the translations of Zhukovsky and Lermontov, try to convey the rhythmic features of each translation when reading.

Phonochristomathy. Listening to an actor's reading

I. F. Schiller. "Glove"

(translation by V. A. Zhukovsky)

- What events does the musical introduction set you up to perceive?

- Why does the actor so diligently reproduce the behavior of a shaggy lion, a brave tiger, two leopards?

- What character traits did the actor convey when reading the heroine’s words addressed to the knight?

- Prepare an expressive reading of the ballad. In your reading, try to reproduce the picture of the splendor and grandeur of the royal palace, the appearance, character, behavior of wild animals, the characters of the beauty and the knight.

Introduction

Creative interaction between director and actor

Introduction

The first thing that stops our attention when we think about the specifics of theater is the essential fact that a work of theatrical art - a performance - is created not by one artist, as in most other arts, but by many participants in the creative process. Playwright, actor, director, musician, decorator, lighting designer, make-up artist, costume designer, etc. - everyone contributes their share of creative work to the common cause. Therefore, the true creator in theatrical art is not an individual, but a team, a creative ensemble. The team as a whole is the author of the performance.

The nature of theater requires that the entire performance be imbued with creative thought and living feeling. Every word of the play, every movement of the actor, every mise-en-scène created by the director should be saturated with them. All of these are manifestations of the life of that single, integral, living organism that receives the right to be called a work of theatrical art - a performance.

The creativity of each artist participating in the creation of the performance is nothing more than an expression of the ideological and creative aspirations of the entire team. Without a united, ideologically cohesive team, passionate about common creative tasks, there cannot be a full-fledged performance. The team must have a common worldview, common ideological and artistic aspirations, and a common creative method for all its members. It is also important that the entire team is subject to the strictest discipline.

“Collective creativity, on which our art is based,” wrote K. S. Stanislavsky, “necessarily requires an ensemble, and those who violate it commit a crime not only against their comrades, but also against the very art they serve.”

Creative interaction between director and actor

The main material in the director's art is the actor's creativity. It follows from this: if the actors do not create, do not think and do not feel, if they are passive, creatively inert, the director has nothing to do, he has nothing to create a performance from, because he does not have the necessary material in his hands. Therefore, the first responsibility of the director is to evoke the creative process in the actor, to awaken his organic nature for full-fledged independent creativity. When this process arises, the second task of the director will be born - to continuously support this process, not to let it go out and direct it towards a specific goal in accordance with the general ideological and artistic concept of the performance.

Since the director has to deal not with one actor, but with a whole team, his third important duty arises - to continuously coordinate the results of the creativity of all actors in such a way as to ultimately create the ideological and artistic unity of the performance - a harmoniously integral work of theatrical art .

The director carries out all these tasks in the process of performing the main function - the creative organization of stage action. Action is always based on one conflict or another. Conflict causes a clash, struggle, and interaction between the characters in the play (it’s not for nothing that they are called characters). The director is called upon to organize and identify conflicts through the interaction of actors on stage. He is a creative organizer of stage action.

But to carry out this function convincingly - so that the actors act on stage truthfully, organically and the audience believes in the authenticity of their actions - is impossible by the method of order and command. The director must be able to captivate the actor with his tasks, inspire him to complete them, excite his imagination, awaken his artistic imagination, and imperceptibly lure him onto the path of true creativity.

The main task of creativity in realistic art is to reveal the essence of the depicted phenomena of life, to discover the hidden springs of these phenomena, their internal patterns. Therefore, a deep knowledge of life is the basis of artistic creativity. Without knowledge of life you cannot create.

This applies equally to the director and the actor. In order for both of them to be able to create, it is necessary that each of them deeply knows and understands that reality, those phenomena of life that are to be displayed on the stage. If one of them knows this life and therefore has the opportunity to creatively recreate it on stage, and the other does not know this life at all, creative interaction becomes impossible.

In fact, let us assume that the director has a certain amount of knowledge, life observations, thoughts and judgments about the life that needs to be depicted on stage. The actor has no baggage. What will happen? The director will be able to create, but the actor will be forced to mechanically obey his will. There will be a one-sided influence of the director on the actor, but creative interaction will not take place.

Now let's imagine that the actor knows life well, but the director knows it poorly - what will happen in this case? The actor will have the opportunity to create and will influence the director with his creativity. He will not be able to receive the opposite influence from the director. The director's instructions will inevitably turn out to be meaningless and unconvincing for the actor. The director will lose his leadership role and will helplessly trail behind the creative work of the acting team. The work will proceed spontaneously, unorganized, creative discord will begin, and the performance will not acquire that ideological and artistic unity, that internal and external harmony, which is the law for all arts.

Thus, both options - when the director despotically suppresses the creative personality of the actor, and when he loses his leading role - equally negatively affect the overall work - the performance. Only with the right creative relationship between the director and the artist does their interaction and co-creation occur.

How does this happen?

Let's say the director gives the actor instructions regarding one or another moment of the role - a gesture, phrase, intonation. The actor comprehends this instruction and internally processes it on the basis of his own knowledge of life. If he really knows life, the director’s instructions will certainly evoke in him a whole series of associations related to what he himself has observed in life, learned from books, from the stories of other people, etc. As a result, the director’s instructions and the actor’s own knowledge, interacting and interpenetrating, form a certain alloy, synthesis. While fulfilling the director’s assignment, the artist will simultaneously reveal himself and his creative personality. The director, having given his thought to the artist, will receive it back - in the form of stage color (a certain movement, gesture, intonation) - “with interest”. His thought will be enriched by the knowledge of life that the actor himself possesses. Thus, the actor, creatively fulfilling the director’s instructions, influences the director with his creativity.

When giving the next task, the director will inevitably build on what he received from the actor when carrying out the previous instruction. Therefore, the new task will inevitably be somewhat different than if the actor had carried out the previous instructions mechanically, i.e., at best, he would have returned to the director only what he received from him, without any creative implementation. The actor-creator will fulfill the next director's instructions, again on the basis of his knowledge of life, and thus will again have a creative impact on the director. Consequently, each director’s task will be determined by how the previous one is completed.

This is the only way creative interaction between director and actor takes place. And only with such interaction does the actor’s creativity truly become the material of director’s art.

It is disastrous for the theater when the director turns into a nanny or guide. How pitiful and helpless the actor looks in this case!

Here the director explained the specific place of the role; not content with this, he went on stage and showed the artist what he had done. how to do it, showed the mise-en-scène, intonation, movements. We see that the actor conscientiously follows the director’s instructions, diligently reproduces what is shown - he acts confidently and calmly. But then he reached the line where the director’s explanations and the director’s show ended. And what? The actor stops, helplessly lowers his hands and asks in confusion: “What next?” He becomes like a wind-up toy that has run out of power. He resembles a man who cannot swim and whose cork belt was taken away in the water. A funny and pathetic sight!

It is the director's job to prevent such a situation. To do this, he must seek from the actor not mechanical performance of tasks, but real creativity. By all means available to him, he awakens the creative will and initiative of the artist, fosters in him a constant thirst for knowledge, observation, and a desire for creative initiative.

A real director is not only a teacher of stage art for an actor, but also a teacher of life. A director is a thinker and a public figure. He is an exponent, inspirer and educator of the team with whom he works. Proper well-being of an actor on stage

So, the director’s first duty is to awaken the actor’s creative initiative and direct it correctly. The direction is determined by the ideological concept of the entire performance. The ideological interpretation of each role must be subordinated to this plan. The director strives to ensure that this interpretation becomes the inherent, organic property of the artist. It is necessary for the actor to follow the path indicated by the director freely, without feeling any violence against himself. The director not only does not enslave him, but, on the contrary, protects his creative freedom in every possible way. For freedom is a necessary condition and the most important sign of the actor’s correct creative well-being, and, consequently, of creativity itself.

The entire behavior of an actor on stage must be both free and faithful. This means that the actor reacts to everything that happens on stage, to all environmental influences in such a way that he has a feeling of the absolute unintentionality of each of his reactions. In other words, it must seem to him that he is reacting this way and not otherwise, because he wants to react this way, because he simply cannot react otherwise. And, in addition, he reacts to everything in such a way that this only possible reaction strictly corresponds to the consciously set task. This requirement is very difficult, but necessary.

Fulfilling this requirement may not be easy. Only when the necessary is done with a sense of freedom, when necessity and freedom merge, does the actor have the opportunity to create.

As long as the actor uses his freedom not as a conscious necessity, but as his personal, subjective arbitrariness, he does not create. Creativity is always associated with free submission to certain requirements, certain restrictions and norms. But if an actor mechanically fulfills the requirements set before him, he also does not create. In both cases, there is no full-fledged creativity. Both the subjective arbitrariness of the actor and the rational game, when the actor forcibly forces himself to fulfill certain requirements, is not creativity. The element of coercion in the creative act must be completely absent: this act must be extremely free and at the same time obey necessity. How to achieve this?

Firstly, the director needs to have endurance and patience, not to be satisfied until the completion of the task becomes an organic need of the artist. To do this, the director not only explains to him the meaning of his task, but also strives to captivate him with this task. He explains and captivates - influencing simultaneously the mind, feeling, and imagination of the actor - until a creative act arises by itself, i.e. until the result of the director’s efforts is expressed in the form of a completely free, as if completely unintentional, involuntary reaction of the actor.

So, the correct creative well-being of an actor on stage is expressed in the fact that he accepts any previously known influence as unexpected and responds to it freely and at the same time correctly.

It is precisely this feeling that the director tries to evoke in the actor and then support him in every possible way. To do this, he needs to know the work techniques that help accomplish this task, and learn to apply them in practice. He must also know the obstacles that the actor faces on the path to creative well-being in order to help the actor eliminate and overcome these obstacles.

In practice, we often encounter the opposite: the director not only does not strive to bring the actor into a creative state, but with his instructions and advice in every possible way interferes with this.

What methods of directing contribute to the actor’s creative well-being and which, on the contrary, hinder its achievement? The language of directorial assignments is action

One of the most harmful methods of directing is when the director immediately demands a certain result from the actor. The result in acting is a feeling and a certain form of its expression, that is, stage color (gesture, intonation). If the director demands that the artist immediately give him a certain feeling in a certain form, then he demands a result. The artist, with all his desire, cannot fulfill this requirement without violating his natural nature.

Every feeling, every emotional reaction is the result of a collision between human actions and the environment. If the actor well understands and feels the goal that his hero is striving for at the moment, and begins quite seriously, with faith in the truth of the fiction, to perform certain actions in order to achieve this goal, there is no doubt: the necessary feelings will begin to come to him by themselves and all his reactions will be free and natural. Approaching the goal will give rise to positive (joyful) feelings; obstacles that arise on the way to achieving the goal will, on the contrary, cause negative feelings (suffering) - the only important thing is that the actor really acts with passion and purpose. The director should require the actor not to depict feelings, but to perform certain actions. He must be able to suggest to the actor not a feeling, but the right action for every moment of his stage life. Moreover: if the artist himself slips into the path of “playing with feelings” (and this happens often), the director must immediately lead him away from this vicious path, try to instill in him an aversion to this method of work. How? Yes, by all means. Sometimes it’s even useful to make fun of what an actor plays feeling, to imitate his performance, to clearly demonstrate its falseness, its unnaturalness and bad taste.

So, directorial assignments should be aimed at performing actions, not at prompting feelings.

By performing the correct actions in the circumstances suggested by the play, the actor finds the correct state of health, leading to creative transformation into the character. Directing assignment form (Showing, explanation and hint)

Any director's instruction can be made either in the form of a verbal explanation or in the form of a show. Verbal explanation is rightly considered the main form of directorial direction. But this does not mean that display should never be used under any circumstances. No, you should use it, but you need to do it skillfully and with a certain amount of caution.

There is no doubt that a director's show is associated with a very serious danger of the creative depersonalization of actors, their mechanical subordination to the director's despotism. However, when used skillfully, very important advantages of this form of communication between the director and the actor are revealed. A complete rejection of this form would deprive directing of a very strong means of creative influence on the actor. After all, only through demonstration can a director express his thoughts synthetically, that is, by demonstrating movement, words and intonation in their interaction. In addition, the director's show is associated with the possibility of emotional infection of the actor - after all, sometimes it is not enough to explain something, you also need to captivate. And finally, the demonstration method saves time: an idea that sometimes takes a whole hour to explain can be conveyed to the actor within two to three minutes using a demonstration. Therefore, you should not give up this valuable tool, but learn how to handle it correctly.

The most productive and least dangerous director's show is in cases where the artist has already reached a creative state. In this case, he will not mechanically copy the director’s show, but will perceive and use it creatively. If the artist is in a creative state, the show is unlikely to help him. On the contrary, the more interesting, brighter, and more talented the director shows, the worse: having discovered the gap between the director’s magnificent show and his helpless performance, the actor will either find himself in an even greater creative grip, or will begin to mechanically imitate the director. Both are equally bad.

But even in cases where the director resorts to showing at the right time, this technique should be used very carefully.

Firstly, one should turn to a show only when the director feels that he himself is in a creative state, knows what exactly he intends to show, experiences a joyful presentiment, or, better said, a creative anticipation of the stage color that he is about to show. In this case, there is a chance that his show will be convincing, bright, and talented. A mediocre show can only discredit the director in the eyes of the acting team and, of course, will not bring any benefit. Therefore, if the director does not feel creatively confident at the moment, then it is better to limit himself to a verbal explanation.

Secondly, the demonstration should be used not so much to demonstrate how to play this or that part of the role, but rather to reveal some significant aspect of the image. This can be done by showing the behavior of a given character in a wide variety of circumstances not provided for by the plot and plot of the play.

It is sometimes possible to show a specific solution to a certain moment of a role. But only if the director has absolute confidence that the actor, who is in a creative state, is so talented and independent that he will reproduce the show not mechanically, but creatively. The most harmful thing is when a director, with stubborn persistence (which, unfortunately, is characteristic of many, especially young directors), strives for an accurate external reproduction of a given intonation, a given movement, a given gesture in a certain place in the role.

A good director will never be satisfied with a mechanical imitation of a show. He will immediately cancel the task and replace it with another if he sees that the actor is not reproducing the essence of what was shown, but only its outer shell. Showing a certain place of the role, a good director will not play it out in the form of a complete acting performance - he will only hint to the actor, only push him, show him the direction in which to look. Going in this direction, the actor himself will find the right colors. What is given in a hint, in embryo, in the director's show, he will develop and complement. He does it on his own, based on his experience, from his knowledge of life.

Finally, a good director in his shows will not proceed from his own acting material, but from the material of the actor to whom he is showing. He will show not how he himself would play a given part of the role, but how this part should be played by a given actor. The director should not look for stage colors for himself, but for the actor with whom he is working.

A real director will not show the same colors to different actors rehearsing the same role. A true director always comes from the actor, because only by coming from the actor can he establish the necessary creative interaction between him and himself. To do this, the director must know the actor with whom he is working perfectly, study all the features of his creative individuality, the originality of his external and internal qualities. And, of course, for a good director, showing is not the main, or even less the only, means of influencing the actor. If the show does not give the expected result, he always has other means in stock to bring the actor into a creative state and awaken the creative process in him.

In the process of implementing the director's plan, three periods are usually distinguished: “table”, in the enclosure and on stage.

The “table” period is a very important stage in the director’s work with the actors. This is laying the foundation for a future performance, sowing the seeds of a future creative harvest. The final result depends greatly on how this period proceeds.

At his first meeting with the actors at the table, the director usually comes with already known baggage - with a certain director's idea, with a more or less carefully developed production project. It is assumed that by this time he had already understood the ideological content of the play, understood why the author wrote it, and thus determined the ultimate task of the play; that he understood for himself why he wants to stage it today. In other words, the director knows what he wants to tell the modern viewer with his future performance. It is also assumed that the director has traced the development of the plot, outlined the end-to-end action and key moments of the play, clarified the relationships between the characters, characterized each character and determined the significance of each in revealing the ideological meaning of the play.

It is possible that by this time a certain “seed” of the future performance had been born in the director’s mind, and on this basis, figurative visions of various elements of the performance began to arise in his imagination: individual actor’s images, parts, mise-en-scène, movements of characters on the stage. It is also possible that all this has already begun to be united in the feeling of the general atmosphere of the play and that the director has imagined, at least in general terms, the external, material environment in which the action will take place.

The clearer for the director himself the creative idea with which he came to the actors at the first rehearsal, the richer and more exciting it is for him, the better. However, the director will make a huge mistake if he immediately lays out all this baggage in its entirety in front of the actors in the form of a report or so-called “director’s explication.” Perhaps the director, in addition to professional talent, also has the ability to express his intentions vividly, imaginatively, and captivatingly. Then, perhaps, he will receive a reward for his report in the form of an enthusiastic ovation from the acting team. But let him not be fooled by this either! The passion gained in this way usually does not last long. The first vivid impression of a spectacular report quickly disappears; the director’s thoughts, without being deeply perceived by the team, are forgotten.

Of course, it is even worse if the director does not have the ability to tell a vivid and captivating story. Then, with the uninteresting form of his premature message, he can immediately discredit even the best, most interesting idea in front of the actors. If this plan contains elements of creative innovation, bold directorial colors and unexpected decisions, then initially this may not only encounter misunderstanding on the part of the team, but also cause a certain protest. The inevitable result of this is the director's cooling of his vision, the loss of creative passion.

It is wrong if the first “table” interviews take place in the form of one-sided directorial declarations and are of a directive nature. Work on a play goes well only when the director's vision has become ingrained in the flesh and blood of the cast. And this cannot be achieved immediately. This takes time, a series of creative interviews are needed, during which the director would not only inform the actors about his plan, but would also check and enrich this plan through the creative initiative of the team.

The initial director's plan is, in essence, not yet a plan. This is just a draft idea. It must undergo a serious test in the process of collective work. As a result of this test, the final version of the director's creative concept will mature.

In order for this to happen, the director must invite the team to discuss issue by issue, everything that makes up the production plan. And let the director himself say as little as possible when putting forward this or that issue for discussion. Let the actors speak. Let them consistently speak out about the ideological content of the play, and about the ultimate task, and about the cross-cutting action, and about the relationships between the characters. Let everyone tell how they imagine the character whose role they are assigned to play. Let the actors talk about the general atmosphere of the play, and about what demands the play makes on acting (in other words, what points in the field of internal and external technique of acting in a given performance should be paid special attention to).

Of course, the director must lead these conversations, fuel them with leading questions, quietly guiding them to the necessary conclusions and the right decisions. But there is no need to be afraid and change your initial assumptions if, in the process of a collective conversation, new solutions emerge that are more correct and exciting.

Thus, gradually becoming more precise and developing, the director's plan will become an organic property of the team and will enter the consciousness of each of its members. It will cease to be the idea of the director alone - it will become the creative idea of the team. This is exactly what the director strives for, this is what he achieves by all means available to him. For only such a plan will nourish the creativity of all participants in the common work.

This is what the first stage of “table” work basically boils down to.

During rehearsals, an effective analysis of the play is practically carried out and an effective line for each role is established.

Each performer at this stage must feel the consistency and logic of their actions. The director helps him in this by determining the action that the actor must perform at any given moment, and giving him the opportunity to immediately try to perform it. Perform at least only in embryo, in a hint, with the help of a few words or two or three phrases of a semi-improvised text. It is important that the actor feels the call to action rather than performs the action itself. And if the director sees that this urge has really arisen, that the actor has understood with body and soul the essence, the nature of the action that he will subsequently perform in an expanded form on stage, that he, for now only for one second, but already for real, ignited by this action, you can move on to analyzing the next link in the continuous chain of actions of this character.

Thus, the goal of this stage of work is to give each actor the opportunity to feel the logic of his role. If the actors have a desire to get up from the table at some point or make some kind of movement, there is no need to restrain them. Let them get up, sit down again in order to figure something out, understand, “pre-justify”, and then get up again. As long as they don’t play around, don’t do more than what they are currently capable of and have the right to do.

One should not think that the “table” period should be sharply separated from the subsequent stages of work - in the enclosure, and then on the stage. It is best if this transition occurs gradually and imperceptibly.

A characteristic feature of the new phase is the search for mise-en-scène. Rehearsals now take place in an enclosure, i.e. in the conditions of a temporary stage installation, which approximately reproduces the conditions of the future design of the performance: the necessary rooms are “blocked off”, the necessary “machines”, stairs, and furniture necessary for the game are installed.

The search for mise-en-scène is a very important stage of working on a performance. But what is mise-en-scène?

Mise-en-scène is usually called the location of the characters on the stage in certain physical relationships to each other and to the material environment surrounding them.

Mise-en-scene is one of the most important means of figurative expression of the director's thought and one of the most important elements in creating a performance. In the continuous flow of successive mise-en-scenes, the essence of the action taking place finds expression.

The ability to create bright, expressive mise-en-scenes is one of the signs of a director’s professional qualifications. The style and genre of the performance is manifested in the nature of the mise-en-scène more than in anything else.

During this period of work, young directors often ask themselves the question: should they develop a project of mise-en-scenes at home, in an office way, or is it better if the director looks for them directly at rehearsals, in the process of live, creative interaction with the actors?

Studying the creative biographies of outstanding directors such as K. S. Stanislavsky, Vl. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, E. B. Vakhtangov, it is not difficult to establish that all of them, in their youth as directors, when working on this or that play, usually drew up the score of the play in advance with detailed mise-en-scenes, i.e. with all the transitions of the characters around the stage, arranging them in certain physical relationships to each other and to surrounding objects, sometimes with precise indications of poses, movements and gestures. Then, during the period of their creative maturity, these outstanding directors usually abandoned the preliminary development of mise-en-scenes, preferring to improvise them in creative interaction with the actors directly during rehearsals.

There is no doubt that this evolution in the method of work is associated with the accumulation of experience, with the acquisition of skills, a certain dexterity, and hence the necessary self-confidence.

Preliminary development of mise-en-scène in the form of a detailed score is as natural for a novice or inexperienced director as improvisation is for a mature master. As for the method of desk work on mise-en-scène itself, it consists of mobilizing imagination and fantasizing. In this process of fantasy, the director realizes himself both as a master of spatial arts (painting and sculpture) and as a master of acting. The director must see in his imagination what he wants to realize on stage, and mentally play out what he saw for each participant in this scene. Only in interaction can these two abilities provide a positive result: internal content, life truthfulness and stage expressiveness of the mise-en-scenes planned by the director.

The director will make a huge mistake if he despotically insists on every mise-en-scène invented at home. He must imperceptibly guide the actor in such a way that this mise-en-scène becomes necessary for the actor, necessary for him, and turns from the director's into the actor's. If in the process of working with an artist it is enriched with new details or even changes completely, there is no need to resist it. On the contrary, you need to rejoice at every good discovery at rehearsal. You need to be ready to change any prepared mise-en-scene for a better one.

When the mise-en-scene is basically completed, the third period of work begins. It takes place entirely on stage. During this period, the final finishing of the performance, its polishing, is carried out. Everything is clarified and secured. All elements of the performance - acting, external design, lighting, makeup, costumes, music, backstage noises and sounds - are coordinated with each other, and thus the harmony of a single and holistic image of the performance is created. At this stage, in addition to the creative qualities of the director, his organizational skills also play a significant role.

The relationship between the director and representatives of all other specialties in theatrical art - whether it be an artist, musician, lighting designer, costume designer or stagehand - is subject to the same law of creative interaction. In relation to all participants in the common cause, the director has the same task: to awaken creative initiative in everyone and correctly direct it. Every artist, no matter what branch of art he works in, in the process of realizing his creative plans is faced with the resistance of the material. The main material in the director's art is the actor's creativity. But mastering this material is not easy. He sometimes puts up very serious resistance.

This often happens. The director seemed to do everything possible to direct the actor on the path of independent creativity: he contributed to the beginning of the study of living reality, tried in every possible way to awaken creative imagination, helped the artist to understand his relationships with other characters, set a number of effective stage tasks for him, and finally went on his own onto the stage and showed, using a number of real-life examples, how these tasks can be accomplished. He did not impose anything on the actor, but patiently waited for him to awaken creative initiative. But, despite all this, the desired result did not work out - the creative act did not occur.

What to do? How to overcome this “material resistance”?

It’s good if this resistance is conscious, if the actor simply does not agree with the director’s instructions. In this case, the director has no choice but to convince. Moreover, a director’s demonstration can provide a considerable service: a convincing and infectious visual demonstration can turn out to be a much more powerful means than all kinds of explanations and logical proofs. In addition, the director always has a way out in this case - he has every right to tell the actor: if you do not agree with what I propose to you, then show yourself what you want, play the way you think is right.

The situation is completely different when the actor resists unconsciously, against his own will: he agrees with the director in everything, he wants to fulfill the director’s task, but nothing works out for him - he has not entered a creative state.

What should the director do in this case? Remove a performer from a role? But the actor is talented, and the role suits him. How to be?

In this case, the director must first of all find the internal obstacle that interferes with the actor’s creative state. Once it is discovered, it will not be difficult to eliminate it.

However, before looking for a creative obstacle in an actor, you should carefully check whether the director himself has made any mistake that caused the actor's block. It often happens that the director torments the artist, demanding the impossible from him. A disciplined actor conscientiously tries to fulfill the director's task, but he fails because the task itself is wrong.

So, in the case of an actor's clamp, the director, before looking for obstacles within the actor, must check his own directorial instructions: are there any significant errors there? This is exactly what experienced directors who know their business do. They easily give up on their assignments. They are careful. They try, feel for the right path.

A director who knows the nature of acting creativity loves and appreciates the actor. He looks for the reason for failure, first of all, in himself, he subjects each of his tasks to strict criticism, he ensures that each of his instructions is not only correct, but also clear and precise in form. Such a director knows that instructions given in a vague, vague form are unconvincing. Therefore, he carefully eradicates from his language all floweriness, all “literary stuff”, and strives for brevity, specificity and maximum accuracy. Such a director does not bore the actors with excessive verbosity.

But let’s assume that the director, for all his conscientiousness and pickiness, did not discover any significant mistakes in himself. Obviously, the obstacle to creativity lies in the actor. How to detect it?

Let us first consider what internal obstacles there are in acting.

Lack of attention to the partner and the surrounding stage environment.

As we know, one of the basic laws of an actor’s internal technique says: every second of his time on stage, the actor must have an object of attention. Meanwhile, it very often happens that the artist sees and hears nothing on stage. A stamp instead of live stage devices becomes inevitable in this case. A living feeling cannot come. The game becomes false. A creative squeeze sets in.

The lack of concentrated attention (or, in other words, the absence of an object on stage that would fully command attention) is one of the significant internal obstacles to acting creativity.

Sometimes it is enough to remove this obstacle so that not a trace remains of the creative constraint. Sometimes it is enough just to remind the actor about the object, just to point out to him the need to truly, and not formally, listen to his partner or to see, really see, the object with which the actor deals as an image, how the actor comes to life...

It also happens. The actor rehearses a crucial part of the role. He squeezes out his temperament, tries to play the feeling, “tears passion to shreds,” plays desperately. At the same time, he himself feels all the falseness of his stage behavior, because of this he becomes angry with himself, angry with the director, with the author, quits acting, starts again and again repeats the same painful process. Stop this actor at the most pathetic point and invite him to carefully examine - well, for example, a button on his partner’s jacket (what color it is, what it’s made of, how many holes there are in it), then his partner’s hairstyle, then his eyes. And when you see that the artist has concentrated on the object given to him, tell him: “Continue playing from the point where you left off.” This is how the director removes the obstacle to creativity, removes the barrier holding back the creative act.

But this doesn't always happen. Sometimes indicating the absence of an object of attention does not give the desired result. So it's not about the object. Obviously, there is some other obstacle preventing the actor from gaining control of his attention.

Muscular tension.

The most important condition for an actor’s creative state is muscular freedom. As the actor masters the object of attention and the stage task, bodily freedom comes to him, and excessive muscular tension disappears.

However, the opposite process is also possible: if the actor gets rid of excessive muscular tension, he will thereby make it easier for himself to master the object of attention and become passionate about the stage task. Very often, the remainder of the reflexively generated muscular tension is an insurmountable obstacle to mastering the object of attention. Sometimes it is enough to say: “Free your right hand” - or: “Free your face, forehead, neck, mouth” for the actor to get rid of the creative constraint.

Lack of necessary stage excuses.

The creative state of an actor is possible only if everything that surrounds him on stage, and everything that happens during the action, is stage-justified for him. If anything remains unjustified for the artist, he will not be able to create. The absence of justification for the slightest circumstance, for the most insignificant fact that the actor faces as an image, can serve as an obstacle to the creative act. Sometimes it is enough to point out to the actor the need to justify some insignificant trifle, which through an oversight remained unjustified, in order to free him from creative pressure.

Lack of creative food can also be a cause of creative blockage.

This happens in cases where the accumulated baggage of observations, knowledge and stage justifications turned out to be used in previous rehearsal work. This baggage fertilized the rehearsal work for a certain time. But the work is not over, and the nutritional material has already dried up. Repeating what was said in the first conversations does not help. Words and thoughts, once expressed and giving a creative result at one time, no longer resonate: they have lost their freshness, they do not excite imagination and do not excite feeling. The actor begins to get bored. As a result, a creative clamp occurs. Rehearsals don't move things forward. And it is known that if an actor does not move forward, he certainly goes back, he begins to lose what he has already found.

What should the director do in this case? It is best if he stops the useless rehearsal and starts enriching the actors with new creative food. To do this, he must again immerse the actors in the study of life. Life is diverse and rich, in it a person can always find something that he had not noticed before. Then the director, together with the actors, will again begin to fantasize about the life that is to be created on stage. As a result, new, fresh, exciting thoughts and words will appear. These thoughts and words will fertilize further work.

The actor's desire to play a feeling. A significant obstacle to an actor’s creativity can be his desire to play at all costs some feeling that he “ordered” for himself. Having noticed such a desire in an artist, we must warn him against this by all means. It is best if the director in this case tells the actor the necessary effective task.

Permitted untruth.

Often, an actor experiences a creative block as a result of falsehoods, untruths, which are sometimes completely insignificant and at first glance unimportant, made during rehearsal and not noticed by the director. This untruth will manifest itself in some trifle, for example, in the way the actor performs a physical task: shakes snow off his coat, rubs his hands chilled in the cold, drinks a glass of hot tea. If any of these simple physical actions are performed falsely, it will entail a number of unfortunate consequences. One untruth will inevitably cause another.

The presence of even a small untruth indicates that the actor’s sense of truth is not mobilized. And in this case he cannot create.

The director's condescending attitude towards the quality of performance of basic tasks is extremely harmful. The actor faked a small physical task. The director thinks: “Nothing, this is nothing, I’ll tell him about it later, he’ll fix it.” And it doesn’t stop the actor: it’s a pity to waste time on trifles. The director knows that now the artist has an important scene to work on, and saves precious time for this scene.

Is the director doing the right thing? No, that's wrong! Artistic truth, which he neglected in an insignificant scene, will immediately take revenge for itself: it will stubbornly not be given into his hands when it comes to the important scene. In order for this important scene to finally take place, it turns out that it is necessary to go back and correct the mistake made, to remove the falsehood.

From this follows a very significant rule for the director: you should never move on without achieving an impeccable execution of the previous scene from the point of view of artistic truth. And don’t let the director be embarrassed by the fact that he will have to spend one or even two rehearsals on a trifle, on some unfortunate phrase. This loss of time will pay off in abundance. Having spent two rehearsals on one phrase, the director can then easily make several scenes at once in one rehearsal: the actors, once directed towards the path of artistic truth, will easily accept the next task and perform it truthfully and organically.

One should protest in every possible way against this method of work, when the director first goes through the entire play “somehow,” admitting falsehood in a number of moments, and then begins to “finish it off” in the hope that when he goes through the play again, he will eliminate the admitted shortcomings. The most cruel misconception! Falsehood has the ability to harden and become stamped. It can become so stamped that nothing can erase it later. It is especially harmful to repeat a scene several times (“run it through,” as they say in the theater), if this scene is not verified from the point of view of the artistic truth of the actor’s performance. You can only repeat what goes right. Even if it is not expressive enough, not clear and bright enough, it’s not a problem. Expressiveness, clarity and brightness can be achieved during the finishing process. If only it were true!

director actor creative ideological

The most important conditions for the creative state of an actor, the absence of which is an insurmountable obstacle. Focused attention, muscular freedom, stage justification, knowledge of life and the activity of fantasy, fulfillment of an effective task and the resulting interaction (stage generalization) between partners, a sense of artistic truth - all these are necessary conditions for the creative state of the actor. The absence of at least one of them inevitably entails the disappearance of others. All these elements are closely related to each other.

Indeed, without concentrated attention there is no muscular freedom, no stage task, no sense of truth; a falsehood admitted in at least one place destroys attention and the organic fulfillment of the stage task in subsequent scenes, etc. As soon as one sins against one law of internal technique, the actor immediately “falls out” of the necessary subordination to everyone else.

It is necessary to restore, first of all, precisely that condition, the loss of which entailed the destruction of all the others. Sometimes it is necessary to remind the actor about the object of attention, sometimes to point out the muscular tension that has arisen, in another case to suggest the necessary stage justification, to enrich the actor with new creative food. Sometimes it is necessary to warn the actor against the desire to “play a feeling” and instead prompt him to take the necessary action, sometimes it is necessary to begin to destroy the untruth that accidentally arises.

The director tries in each individual case to make the correct diagnosis, to find the main cause of creative blockage in order to eliminate it.

It is clear what kind of knowledge of the acting material, what a keen eye, what sensitivity and insight a director should have.

However, all these qualities are easily developed if the director appreciates and loves the actor, if he does not tolerate anything mechanical on stage, if he is not satisfied until the actor’s performance becomes organic, internally filled and artistically truthful.

Bibliography

· “The Skill of the Actor and Director” is the main theoretical work of the People's Artist of the USSR, Doctor of Art History, Professor Boris Evgenievich Zakhava (1896-1976). · B. E. Zakhava The skill of an actor and director: A textbook. 5th ed.

Actors or even sales managers, and sometimes beggars, swindlers and artists need to convey one character or another. In order to fully integrate into the image and accurately convey the character’s character, you need to do a lot of work. The influence of character on the result is enormous, so understanding the role should be given special importance.

If we are talking about theater or cinema, then the character of the actor should not be reflected in the character of the character. However, in reality it happens somewhat differently. When a famous literary work, or more often a biographical work, is filmed or staged, then the actor’s self must recede into the background. If it is necessary to get used to the role of a hero still unknown to the public, then each actor or actress tries to add their own charm to the image, to introduce some individual traits. Each performer brings his own understanding and presentation to the image. So, sometimes serial killers become touching and tender, and housewives become greedy and cruel.

Literary hero and cover. Nature of the work

To convey the image of a literary hero, it is not enough to simply read the work. You can read a novel to its core, but the image and character of your character will remain incomprehensible. It’s worth trying to study reviews of the work, and perhaps turn to film adaptations. If such methods do not help, then it is advisable to get used to his role as much as possible. When we look at the lost Robinson, we want a theater or film actor to try and live at least a day or an hour in such conditions. Then his understanding of the role will become completely different. But not all roles allow such experimentation; otherwise, the number of murderers, thieves and swindlers, as well as lovers and heroes, has steadily increased as new films or theatrical productions have been released.

What if the image of the character has not only never been found in literature, but is an absolute innovation of the screenwriter and requires special acting talent to be embodied? Then it’s worth looking closely at the character of the work, because the plot and the plot carry a lot of information about the character, her perception, and actions. The image may be quite stereotypical, but details, insignificant for many actions, will become decisive for the final character. It should not be surprising that many brilliant actors and all kinds of characters were the result of funny improvisations and force majeure, which led to the appearance of various details or lines. However, it is important to read the script as much as possible, try to replay all the events in your thoughts, and look at your character as if from the outside. Only in this way, through careful analysis, can a high-quality and subtle conveyance of the character’s character be achieved.

The series of films about Pirates of the Caribbean has become, perhaps, the most successful of Disney projects in recent times. It is a phenomenal success, both in the West and here in Russia, and the main character, the charismatic pirate Jack Sparrow, has become one of the most popular movie characters.

The image of the hero offered to us is quite curious and it did not appear by chance. It’s all the more interesting to take a closer look at it. Jack Sparrow is a pirate, a man without a home, without a homeland, without roots. He is a sea robber. Not Robin Hood, robbing the rich to help the poor. He is only interested in his own enrichment, he does not care about everyone else. Jack dreams of finding a ship on which he could sail beyond the distant seas, “a ship to call at port once every ten years; to the port, where there will be rum and dissolute girls.” He is a classic individualist. In one of the episodes, the pirates turn to Jack for help: “The pirates are going to fight Becket, and you are a pirate... if we don’t unite, they will kill us all except you,” his friends or enemies turn to him. “Sounds interesting,” Jack replies. He does not need friends, he craves absolute freedom from any obligations.

This desire for freedom makes the image of Jack very attractive - especially for teenagers. It is clearly addressed to a greater extent to them, to their desire to break away from their parents and become independent. Interestingly, Hollywood films often exploit some aspects of adolescence while ignoring others. After all, along with the desire to break old connections, teenagers also have a desire to form new ones. They are very willing to unite in various groups and movements. Teenagers make the most dedicated people. They passionately search for meaning like no other. All kinds of fan youth movements are proof of this. This means that along with “freedom from” there is “freedom for”, and the latter is no less attractive. So why aren't Hollywood movie makers turning to it?

“Freedom from” itself, which involves breaking all ties with the world, is destructive. The history of Europe and America since the end of the Middle Ages is the history of the gradual liberation of man, his acquisition of ever greater rights and freedoms. But few people talk about the negative factors accompanying this liberation. Erich Fromm, a prominent German philosopher and social psychologist who studied the influence of political and economic development of society on the human psyche, wrote: “The individual is freed from economic and political shackles. He also gains positive freedom - along with the active and independent role that he has to play in the new system - but at the same time he is freed from the ties that gave him a sense of confidence and belonging to some community. He can no longer live his whole life in a small little world, the center of which was himself; the world has become limitless and threatening. Having lost his specific place in this world, a person also lost the answer to the question about the meaning of his life, and doubts fell upon him: who is he, what is he, why does he live? He is threatened by powerful forces that stand above the individual - capital and the market. His relations with his brothers, in each of whom he sees a possible competitor, have acquired the character of alienation and hostility; he is free - that means he is lonely, isolated, threatened from all sides.”

Along with freedom, a person acquires the powerlessness and uncertainty of an isolated individual who has freed himself from all the bonds that once gave life meaning and stability.

This sense of instability is very evident in the character of Jack himself. He is a pirate - a man literally without ground under his feet. He walks somehow strangely: on his toes and as if swaying. The appearance of such an individualistic hero, breaking ties with the world, running away from obligations, a person who trusts no one and loves no one, a person without goals, attachments and interests is natural. Jack Sparrow is the end product of the modern evolution of social consciousness, a “free man,” so to speak.

To be fair, it should be said that Jack Sparrow does have one goal. He really wants to become immortal. The appearance of such a desire is also quite natural, since an intense fear of death is an experience very typical of people like the charming, cheerful Jack. For it - the fear of death, inherent in everyone - tends to intensify many times over when a person lives his life meaninglessly, in vain. It is the fear of death that drives Jack in search of the source of eternal youth.

Denial of death is a characteristic feature of modern Western pop culture. Endlessly replicated images of skeletons and skulls and crossbones are nothing more than an attempt to make death something close, funny, an attempt to make friendly friends with it, to escape from the awareness of the tragic experience of the finitude of life. “Our era simply denies death, and with it one of the fundamental aspects of life. Instead of turning the awareness of death and suffering into one of the strongest stimuli of life - the basis of human solidarity, the catalyst without which joy and enthusiasm lose intensity and depth - the individual is forced to suppress this awareness,” says Fromm. Jack does not have the courage to realize the inevitability of death, he hides from it.

So, Jack Sparrow's “freedom” turns him into a frightened, lonely man who treats the world with distrust and aloofness. This alienation and mistrust prevent him from resorting to traditional sources of consolation and protection: religion, family values, deep emotional attachment to people, service to an idea. All this is consistently devalued in modern Western culture. “Manifestations of selfishness in a capitalist society become the rule, and manifestations of solidarity become the exception,” says Fromm.

Why does Hollywood so diligently reproduce countless clones of the “maverick hero” model? Why does it replicate the image of a selfish, distrustful person deprived of consolation? According to Fromm, a person deprived of consolation is an ideal consumer. Consumption tends to reduce anxiety and restlessness. Deprived of spiritual sources of consolation, a person rushes to material sources that can only offer temporary peace, a surrogate. Stimulating consumption is one of the main tasks of a market economy. And it doesn’t matter that the joy of an acquisition can drown out anxiety for a very short time, that pleasure is replaced by true happiness.

In order to make the goods-pleasure bond stronger, a person’s basest qualities are disinhibited, thereby destroying the soul. Consequently, any idea that professes the priority of spiritual values and disdain for material values must be discredited. Christianity and communism, with their ideas about humanism and dreams of the spiritual ascent of man, are especially fiercely attacked. This is why priests in Hollywood films are often portrayed as either funny and weak or harsh, suppressive individuals, and people of faith as crazy fanatics. Business is not interested in the spiritual growth of a person; it needs a consumer who, in vague anxiety, is forced to wander through hypermarkets in search of peace of mind, just as Captain Jack Sparrow forever wanders the world without purpose or meaning.