Scriabin's main works. Alexander Scriabin: biography, interesting facts, creativity

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.site/

SKRYABIN, ALEXANDER NIKOLAEVICH (1872-1915), Russian composer and pianist. Born December 25, 1871 (January 6), 1872 in Moscow. After graduating from the Moscow Conservatory (where he studied, in particular, with A.S. Arensky and S.I. Taneev), Scriabin began giving concerts and teaching, but soon concentrated on composing. Scriabin's main achievements are associated with instrumental genres (piano and orchestral; in some cases - the Third Symphony and Prometheus - a choir part is introduced into the scores). Scriabin's mystical philosophy was reflected in his musical language, especially in innovative harmony, far beyond the boundaries of traditional tonality. The score of his symphonic Poem of Fire (Prometheus, 1909-1910) includes a light keyboard (Luce): rays of spotlights of different colors should change on the screen synchronously with changes in themes, keys, and chords. Scriabin's last work was the so-called. Preliminary performance for soloists, choir and orchestra - a mystery, which, according to the author's plan, was supposed to unite humanity (remained unfinished).

Scriabin is one of the largest representatives of artistic culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A brave innovator, he created his own sound world, his own system of images and means of expression. Scriabin's work was influenced by idealistic philosophical and aesthetic movements. The bright contrasts of Scriabin's music, with its rebellious impulses and contemplative detachment, sensual yearning and imperative exclamations, reflected the contradictions of the complex pre-revolutionary era.

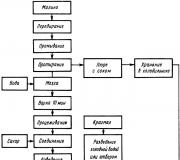

The main area of Scriabin's creativity is piano and symphonic music. In the legacy of the 80s-90s. The genre of romantic piano predominates. miniatures: preludes, etudes, nocturnes, mazurkas, impromptu. These lyrical plays capture a wide range of moods and states of mind, from soft dreaminess to passionate pathos. The sophistication and nervous aggravation of emotional expression characteristic of Scriabin is combined in them with a noticeable influence of F. Chopin, and partly A.K. Lyadov. The same images prevail in the major cyclical works of these years: a piano concerto (1897), 3 sonatas (1893, 1892-97, 1897).

Scriabin's family belonged to the Moscow noble intelligentsia. The parents, however, did not have the chance to play a noticeable role in the life and upbringing of their brilliant son, born on January 6, 1872. His mother soon died of tuberculosis, and his father, a lawyer, spent a lot of time doing his own business. Sasha’s ear for music and memory amazed those around him. From an early age, he could easily reproduce by ear a melody he heard once, picking it up on the piano or other instruments that came to hand. But little Scriabin’s favorite instrument was the piano. Not yet knowing the notes, he could spend many hours at it, even to the point of rubbing the soles of his shoes with the pedals. “That’s how the soles burn, that’s how the soles burn,” his aunt lamented.

The time has suddenly come to think about Sasha’s general education. His father wanted him to enter the lyceum. However, the family gave in to the desire of everyone's favorite - to definitely enroll in the cadet corps. In the fall of 1882, ten-year-old Alexander Scriabin was accepted into the 2nd Moscow Cadet Corps.

Gradually, Sasha decided to enter the conservatory. Continuing his studies in the corps, he began to study privately with the prominent Moscow teacher N. Zverev.

In parallel with his studies with Zverev, Scriabin began taking lessons in music theory from Sergei Ivanovich Taneyev. In January 1888, at the age of 16, Scriabin entered the conservatory. At the same time, Scriabin was also accepted into the piano class. Here Vasily Ilyich Safonov, a major musical figure, pianist and conductor, became his teacher.

Very soon Scriabin, along with Rachmaninov, attracted the attention of teachers and comrades. Both of them took the position of conservative “stars” who showed the greatest promise. Alexander studied in Taneyev’s class for two years. Taneyev appreciated the talent of his student and treated him personally with great warmth. Scriabin responded to the teacher with deep respect and love. The works created by Scriabin during his studies were written almost exclusively for his favorite instrument. He composed a lot during these years. In his own list of his compositions for the years 1885-1889, more than 50 different plays are named. In February 1894, he performed for the first time in St. Petersburg as a pianist performing his own works. Here he met the famous musical figure M. Belyaev. This acquaintance played an important role in the initial period of the composer’s creative path.

Through Belyaev, Scriabin began relationships with Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, Lyadov and other St. Petersburg composers.

In the mid-1890s, Scriabin's performing activities began. He performs concerts of his compositions in various cities of Russia, as well as abroad. In the summer of 1895, Scriabin's first foreign tour took place. At the end of December of the same year, he went abroad again, this time to Paris, where he gave two concerts in January.

Reviews from French critics about the Russian composer were generally positive, some even enthusiastic. His individuality, exceptional subtlety, and special, “purely Slavic” charm were noted. In addition to Paris, Scriabin also performed in Brussels, Amsterdam, and The Hague. In subsequent years he visited Paris several times. At the beginning of 1898, a large concert of Scriabin’s works took place here, in some respects unusual: the composer performed together with his pianist wife Vera Ivanovna Scriabin (née Isakovich), whom he had married shortly before. Of the five sections, Scriabin himself played in three, and Vera Ivanovna, with whom he alternated, played in the other two. The concert was a huge success.

In the autumn of 1898, Scriabin accepted an offer from the Moscow Conservatory to take over the leadership of the piano class and became one of its professors.

Among the small works of these years, the first place is occupied by preludes and etudes. The cycle of 12 etudes he created in 1894-1895 represents the most remarkable examples of this form in world piano literature. The last etude (in D sharp minor), sometimes called “pathetic,” is one of the most inspired courageous and tragic works of the early Scriabin.

In addition to small-form pieces, Scriabin also created a number of large piano works during these years. He wrote his first sonata just a year after graduating from the conservatory. Important in Scriabin’s creative development is his Third Sonata. Here, for the first time, the idea that later formed the basis of his symphonic works was clearly embodied - the need for an active struggle to achieve a goal, based on an unshakable conviction in the final triumph.

At the end of the 1890s, new creative tasks forced the composer to turn to the orchestra, to which he devoted his main attention for a while. It was a period of great creative growth. He discovered the still undiscovered great possibilities hidden in his talent. In the summer of 1899, Scriabin began composing the First Symphony. It was mostly completed in the same year. The music of the symphony captivates with romantic excitement and sincerity of emotions. Following the First Symphony, Scriabin composed the Second in 1901, continuing and developing the circle of images outlined in its predecessor. At the end of the century, Scriabin became a member of the Moscow Philosophical Society. Communication there, together with the study of special philosophical literature, determined the general direction of his views.

These sentiments led him to the idea of “Mystery,” which from now on became for him the main work of his life. “Mystery” was presented to Scriabin as a grandiose work that would unite all types of art - music, poetry, dance, architecture, etc. However, according to his idea, this was not supposed to be a purely artistic work, but a very special collective “action”, in which no less than all of humanity would take part! There will be no division between performers and listeners-spectators. The fulfillment of the “Mystery” should entail some kind of grandiose world revolution.

The idea amazed even the author himself with its grandeur. Afraid to approach him, he continued to create “ordinary” musical works. Less than a year after finishing the Second Symphony, Scriabin began composing the Third. However, its composition proceeded relatively slowly. But during several summer months of the same 1903, Scriabin wrote a total of more than 35 piano works, so great was the creative upsurge he experienced at that time.

In February 1904, Scriabin went abroad for several years. Scriabin spent the following years in various Western countries - Switzerland, Italy, France, Belgium, and also toured America. In November 1904, Scriabin completed his Third Symphony. An important event in his personal life dates back to this time: he separated from his wife Vera Ivanovna. Scriabin's second wife was Tatyana Fedorovna Shletser, the niece of a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Tatyana Fedorovna herself had a musical background and at one time even studied composition (her acquaintance with Scriabin began through theory classes with him). But, admiring Scriabin’s work, she sacrificed all her personal interests for his sake.

In Paris on May 29, 1905, the first performance of the Third Symphony took place - it became a wonderful monument to Russian and world symphonic music of the early 20th century. Despite its pronounced originality, it has clear connections with the traditions of domestic and foreign music. After the performance of the Third Symphony, the composer began to work on the next largest symphonic work, the “Poem of Ecstasy,” which he initially called the Fourth Symphony. Elation and bright emotions attract attention in this poem, completed by the composer and written in 1907.

A year later, Scriabin conceived the idea of the next major orchestral work - the poem “Prometheus”. The music of the poem was mainly in 1909.

The peculiarities of the plan led to non-standard means for implementation. The most unusual detail of the huge Prometheus score, reaching up to 45 lines, is a special line of music marked with the word “light”. It is intended for a special, not yet created instrument - a “light keyboard”, the design of which Scriabin himself imagined only approximately. It was assumed that each key would be connected to a light source of a certain color of life.

The first performance took place on March 15, 1911. “Prometheus” gave rise, as contemporaries put it, “fierce disputes, ecstatic delight of some, mockery of others, and for the most part, misunderstanding and bewilderment.” In the end, however, it was a huge success: the composer was showered with flowers, and for half an hour the audience did not leave, calling the author and conductor.

In the last two years of his life, Scriabin’s thoughts were occupied by a new work (still unfinished due to his death) - “Preliminary Action”.

As its name shows, it was supposed to be something like a “dress rehearsal” of “Mystery” - its, so to speak, “light” version. In the summer of 1914, World War I broke out. In this historical event, Scriabin saw, first of all, the beginning of processes that were supposed to bring the “Mystery” closer.

In Scriabin's symphonies there is still a noticeable connection with the traditions of the dramatic symphonism of P. I. Tchaikovsky, with the work of R. Wagner and F. Liszt. Symphonic poems are original works both in concept and in implementation. Themes acquire the aphoristic brevity of symbols denoting a particular state of mind (themes of “languor,” “dream,” “flight,” “will,” “self-affirmation”). In the mode-harmonic sphere, instability, dissonance, and exquisite spice of sound prevail. The texture becomes more complex, acquiring multi-layered polyphony. In the 1900s The piano also developed in parallel with the symphonic piano. Scriabin’s work, which embodies the same ideas, the same range of images in the chamber genre. For example, the 4th and 5th sonatas (1903, 1907) are a kind of “companions” of the 3rd symphony and the “Poem of Ecstasy”. The tendency towards concentration of expression and compression of the cycle is also similar. Hence, one-movement sonatas and piano poems are a genre that was of utmost importance in the late period of Scriabin’s work. Among the piano works of recent years, the central place is occupied by the 6th-10th sonatas (1911-13) - a kind of “approach” to the “Mystery”, a partial, sketchy embodiment of it. Their language and figurative structure are highly complex and somewhat encrypted.

Scriabin seems to be striving to penetrate the region of the subconscious, to record in sounds suddenly arising sensations and their bizarre changes. Such “captured moments” give rise to short symbolic themes that make up the fabric of the work. Often one chord, a two- or three-note intonation, or a fleeting passage acquires an independent figurative and semantic meaning. Scriabin's work had a significant impact on the development of piano and symphonic music of the 20th century.

This portrait of Scriabin at the piano and Koussevitzky at the conductor's stand was painted by Robert Sterl, a German friend of Russian composers. and in particular, Rachmaninoff, whom Sterl also wrote on several occasions.

In the first months of 1915, Scriabin gave many concerts. In February, two of his performances took place in Petrograd, which were very successful. In this regard, an additional third concert was scheduled for April 15. This concert was destined to be the last.

Returning to Moscow, Scriabin felt unwell a few days later. He developed a carbuncle on his lip. The abscess turned out to be malignant, causing general blood poisoning. The temperature has risen. In the early morning of April 27, Alexander Nikolaevich passed away.

A.N. was buried. Scriabin at the Novodevichy cemetery.

Alexander Nikolaevich had seven children in total: four from his first marriage (Rimma, Elena, Maria and Lev) and three from his second (Ariadna, Julian and Marina). Three of them died in childhood, far from reaching adulthood. In his first marriage (to the famous pianist Vera Isakovich), out of four children (three daughters and one son), two died at an early age. The first (being seven years old) to die was the Scriabins' eldest daughter - Rimma (1898--1905) - this happened in Switzerland, in the holiday village of Vezna near Geneva, where Vera Scriabina lived with her children. Rimma died on July 15, 1905 in the cantonal hospital from volvulus.

Scriabin himself by that time lived in the Italian town of Bogliasco - already with Tatyana Schlötser, his future second wife. “Rimma was Scriabin’s favorite and her death deeply shocked him. He came to the funeral and wept bitterly over her grave.<…>This was Alexander Nikolaevich’s last meeting with Vera Ivanovna.”

Scriabin's eldest son, Lev was the last child from his first marriage; he was born in Moscow on August 18/31, 1902. Like Rimma Scriabin, he died at the age of seven (March 16, 1910) and was buried in Moscow in the cemetery of the Monastery of All Who Sorrow Joy on Novoslobodskaya Street (the monastery does not currently exist). By that time, Scriabin’s relationship with his first family was completely ruined, more reminiscent of the Cold War, and the parents did not even meet at their son’s grave. Of the two (long-awaited) sons of Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin, only one, Julian, was still alive by that time.

Ariadna Scriabina converted to Judaism with her first marriage, married the poet Dovid Knut with her third marriage, with whom she participated in the Resistance movement in France, was tracked down by the Vichy police in Toulouse during a mission to transport refugees to Switzerland and died in a shootout on June 22, 1944 when attempting to arrest. A monument was erected to her in Toulouse, and on the house where A. Scriabina died, members of the Zionist Youth Movement of Toulouse erected a memorial plaque with the inscription: “In memory of Regine Ariadne Fixman, who heroically died at the hands of the enemy on 22--VII-- 1944, defending the Jewish people and our homeland, the Land of Israel."

The composer's son, Yulian Scriabin, who died at the age of 11, was himself a composer whose works are still performed today.

Alexander Nikolaevich's half-sister Ksenia Nikolaevna was married to Boris Eduardovich Bloom, Scriabin's colleague and subordinate. Court Counselor B. E. Bloom then served in the mission in Bukhara, and in 1914 he was listed as vice-consul in Colombo in Ceylon, where he was “seconded to strengthen the personnel of the political agency,” although he did not travel to the island. On June 19, 1914, in Lausanne, their son Andrei Borisovich Bloom was born, who, under the monastic name “Anthony,” would later become the famous preacher and missionary Metropolitan of Sourozh (1914-2003).

Prometheus (Poem of Fire) Op. 60-- musical poem (duration 20-- 24 minutes) by Alexander Scriabin based on the myth of Prometheus for piano, orchestra (including organ), voice (choir ad libitum) and “light keyboard” (Italian tastiera per luce), representing a disk on which twelve colored light bulbs with the same number of switches connected by wires were installed in a circle. When the music was played, the lights flashed in different colors.” Another of the innovative ideas used by Scriabin was the construction of a musical fabric from a single structure - a chord, which was later called “Promethean”.

The work was composed in 1908-1910. and was first performed on March 2 (15), 1911 in Moscow by an orchestra conducted by Sergei Koussevitzky. The premiere took place without a lighting party, since the apparatus was not suitable for performance in a large hall.

With the lighting part, Prometheus was first performed on May 20, 1915 in New York's Carnegie Hall by the Orchestra of the Russian Symphony Society conducted by Modest Altshuler. For this premiere, Altshuler ordered a new light instrument from engineer Preston Millar, to which the inventor gave the name “chromola”; The performance of the lighting part caused numerous problems and was coldly received by critics. According to press reports at the time, the public premiere was preceded by a private performance on February 10 in a narrow circle of selected connoisseurs, including Anna Pavlova, Isadora Duncan and Misha Elman.

In the 60-70s. interest arose again in performing Scriabin's work with a lighting part. In 1962, according to director Bulat Galeev, the full version of “Prometheus” was performed in Kazan, and in 1965. A light and music film was made to Scriabin's music. In 1972, the performance of the poem by the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of the USSR under the direction of E. Svetlanov was recorded at the Melodiya company. On May 4, 1972, Prometheus was performed with lighting by the London Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Eliakum Shapira at the Royal Albert Hall in London. On September 24, 1975, the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Dixon, performed the poem for the first time, accompanied by a laser show designed by Lowell Cross (this concert was filmed and edited as a documentary film, and re-released on DVD in 2005).

Among the most notable recordings of “Prometheus” are performances by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado (piano part Martha Argerich), the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Pierre Boulez, soloist Anatoly Ugorsky), and the Philadelphia Orchestra (conducted by Riccardo Muti, soloist Dmitry Alekseev) , London Philharmonic Orchestra (conducted by Lorin Maazel, soloist Vladimir Ashkenazy).

The premiere of the new symphonic work became the main event of Russian musical life. This happened on March 9, 1911 in St. Petersburg in the hall of the Noble Assembly, the same one that now belongs to the St. Petersburg State Philharmonic. The famous Koussevitzky conducted. The author himself was at the piano. It was a huge success. A week later, "Prometheus" was repeated in Moscow, and then sounded in Berlin, Amsterdam, London, and New York. Light music - that was the name of Scriabin's invention - fascinated many at that time; new light-projection devices were designed here and there, promising new horizons for synthetic sound-color art.

But even at that time, many were skeptical about Scriabin’s innovations - the same Rachmaninov, who once, while examining “Prometheus” at the piano in Scriabin’s presence, asked, not without irony, what color it was. Scriabin was offended.

This fragile, short man, who harbored titanic plans and was distinguished by his extraordinary capacity for work, possessed, despite a certain arrogance, a rare charm that attracted people to him. His simplicity, childlike spontaneity, and the open trustfulness of his soul were captivating. He also had his own little eccentricities - for many years he stroked the tip of his nose with his fingers, believing that in this way he would get rid of his snub nose, he was suspicious, was afraid of all kinds of infections and did not go out into the street without gloves, did not take money in his hands, and while drinking tea he warned not to picked up a dryer that had fallen from a plate from the tablecloth - there could be germs on the tablecloth...

Alexander Scriabin, the most unknown Russian composer, who managed to look into the highest transcendental spheres, possessed the rarest and most amazing gift - synesthesia, or “color hearing,” when music gives rise to color associations and vice versa, when color evokes sound experiences. Among Russian composers there is no other genius who would be as mystical as Alexander Scriabin. His creations are a sacred act, magic, whose mysterious formulas are woven into musical symbols.

SECRETS OF THE “PROMETHEAN CHORD” The esoteric plan of the “Poem of Fire” goes back to the secret of the “world order”. The famous “Promethean chord” - the entire sound basis of the work - is perceived as a “chord of the Pleroma”, a symbol of the completeness and mystery of the power of existence. The hexagonal “crystal” of the “Promethean chord” is similar to the “Solomon’s seal” (or that six-pointed one, which is symbolically depicted at the bottom of the cover of the score). In the “Poem of Fire” there are 606 bars - a sacred number that corresponds to triadic symmetry in medieval church painting, related to the theme of the Eucharist (6 apostles to the right and left of Christ). In “Prometheus” the proportions of the “golden section” are precisely observed. Particular attention to the final part of the choir. “Prometheus” for Scriabin meant a new stage in the embodiment of the principle of the Absolute in music.

“Prometheus” (“Poem of Fire”) occupies a special place in the work of Alexander Scriabin and is completely unique in the world space. It is not only a synthesis of music and light, but also an encrypted teaching, a fusion of hidden symbols and, probably, a new Bible consisting of sounds. This is total harmony, the embodiment of the theosophical principle “everything is in everything,” and the presence of hidden meanings in the poem is amazing.

The choice of the hero, the fire thief Prometheus, was not at all accidental for Scriabin: “Prometheus is the active energy of the Universe, the creative principle. This is fire, light, life, struggle, thought. Progress, civilization, freedom,” said the composer. He was obsessed with the idea of creating world harmony out of chaos. But were angels or demons standing behind Alexander Scriabin when he wrote this poem? Scriabin was fascinated by fire. Not only the “Poem of Fire” was “fiery”. Alexander Nikolaevich also owns earlier works on the same topic: the poem “To the Flame” and the play “Dark Lights”. And in each of these creations, not only (and sometimes not so much) the life-giving fiery power was glorified, but also another, demonic hypostasis of the fiery element, carrying within itself an element of a magical spell and devilish spells.

All researchers of the composer's work agree that Scriabin's Prometheus bears the features of Lucifer. The composer’s striking statement is well known: “Satan is the yeast of the universe.” For Scriabin, Lucifer was not so much evil as... a “bearer of light” (lux + fero), a luminous mission. But what color was that “light” of Scriabin’s Prometheus-Lucifer? It turns out it's blue-purple. According to the composer’s light and sound system, the tonality F sharp, the main tonality of the “Poem of Fire,” corresponds to it. Surprisingly, the same blue-purple palette is present in the works of other mystics who metaphysically contemplated other spheres of existence: Vrubel’s demons are blue-purple, Blok’s famous “Stranger” is also permeated with blue-purple tones. The poet himself spoke of “The Stranger” as “a devilish alloy from many worlds, mainly blue and purple.” Daniil Andreev in his “Rose of the World,” when describing the devilish layers, resorts to the following descriptions: “lilac ocean,” “infralilac glow,” “a luminary of an unimaginable color, vaguely reminiscent of violet.”

Poem of ecstasy. A distinctive feature of Scriabin's work is the extraordinary intensity of spiritual development. Scriabin was not only a composer and pianist, but also a philosopher. He did not have a special philosophical education, but already from the early 1900s he took part in the philosophical circle of S.N. Trubetskoy, carefully studied the works of Kant, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel. But he didn’t stop in any of these directions. All this served only as a basis for his own mental constructions, which were reflected in his music. Over the years, the composer's philosophical views expanded and transformed, but their basis remained unchanged. This basis was the idea of the divine meaning of creativity and the theurgic, transformative mission of the artist-creator. Under its influence, the content, the “philosophical plot” of Scriabin’s works is also formed. This plot depicts the development and formation of the Spirit: from a state of constraint to the heights of self-affirmation. Ups and downs in all musical manifestations are a characteristic feature of Scriabin's style. The principle of comparison and interpenetration of contrasts - grandiose and refined, active-willed and dreamily-languorous - permeates the dramaturgy of the composer’s symphonic works - the Third Symphony, “Poem of Ecstasy”.

Scriabin did not “specially” search for musical language. His language, which all his contemporaries unanimously recognized as innovative, was a natural manifestation for Scriabin, a worthy means for embodying the ideas that he wanted to convey to his listeners. “I’m going to tell people that they are strong and powerful, that there is nothing to grieve about, that there is no loss! So that they are not afraid of despair, which alone can give rise to real triumph. Strong and powerful is the one who has experienced despair and defeated it,” the composer wrote in his diary. Scriabin Prometheus third symphony

Scriabin sees the idea of transformation, the victory of the spiritual over the material in the following dramatic triad: languor - flight - ecstasy. These images and psychological states permeate not only the composer’s symphonic works, but also his piano miniatures, because Scriabin was the greatest pianist of his time, actively giving concerts all over the world.

Scriabin. Symphony No. 3, C minor, Op. 43, "Divine Poem"

Symphony no. 3 in C minor, Op. 43, "The Divine Poem"

03/18/2011 at 15:43.

Orchestra composition: 3 flutes, piccolo flute, 3 oboes, cor anglais, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 5 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, tom-tam, glockenspiel, 2 harps, strings.

History of creation

At the end of the 1902-1903 academic year, Scriabin left his position as a professor at the conservatory, since teaching was a burden to him and did not give him the opportunity to fully devote himself to creativity. In the summer, at the dacha, he worked a lot. He entered into an agreement with the St. Petersburg philanthropist and music publisher M. Belyaev, according to which Belyaev paid the composer a monthly amount sufficient for the life of the family, and Scriabin covered these amounts by providing his works for publication. He was seriously in debt to the publishing house: the amount was so large that he had to compose thirty piano pieces to pay off. Meanwhile, the composer's thoughts were occupied with the new, Third Symphony.

The summer passed in intense work - the Fourth Piano Sonata, the Tragic and Satanic Poems, and the Preludes op. 37, etudes op. 42. And at the same time, the idea of the Third Symphony took shape so much that, having arrived in St. Petersburg in early November, Scriabin was able to introduce his musician friends to it. He wrote to his wife: “Yesterday evening I finally performed my symphony in front of a host of St. Petersburg composers and, oh surprise! Glazunov is delighted, Korsakov is very supportive. At dinner they even raised the question that it would be nice to force Nikish to perform it... I am also happy for Belyaev, who will now publish it with pleasure.”

Now Scriabin could go abroad - he had long dreamed of living in Switzerland. However, a month later, Belyaev died unexpectedly, and Scriabin found himself without the support to which he had become accustomed over many years of their friendship. It was not yet clear how relations with Belyaev’s successors would develop. A wealthy student of Scriabin, M. Morozova, came to the rescue and offered an annual subsidy. The composer gratefully accepted her and in February 1904 settled in Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Geneva. Here he completed the Third Symphony, after which he went to Paris to negotiate its performance.

T. Schletser came to him in Paris, who selflessly fell in love with the composer and decided to unite her life with him, despite the fact that Scriabin’s wife did not give him a divorce. Having a perfect understanding of the composer’s music and his philosophical quests, Schletser wrote a literary program (in French) for the premiere of the Third Symphony, which the composer authorized. It is as follows: “The “Divine Poem” represents the development of the human spirit, which, breaking away from a past full of beliefs and secrets, overcomes and overthrows this past and, passing through pantheism, comes to an intoxicating and joyful affirmation of its freedom and its unity with the universe (divine "I")".

The first part is “Struggles”: “The struggle between man - the slave of a personal God, the supreme ruler of the world, and a powerful, free man, a man-god. The latter seems to be triumphant. But so far only reason rises to the affirmation of the divine “I,” while the personal will, still too weak, is ready to fall into the temptation of pantheism.”

The second part is “Pleasures”: “A person surrenders to the joys of the sensory world. Pleasures intoxicate and lull him; he is absorbed in them. His personality disappears into nature. And then, from the depths of his being, Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin, the consciousness of the sublime rises, which helps him overcome the passive state of his human self.”

Third part, “The Divine Game”: “The spirit, freed at last from all the bonds connecting it with the past, filled with submission to a higher power, the spirit producing the universe with the sole power of its creative will and recognizing itself as one with this universe, surrenders to the sublime the joy of free activity—“divine play”.”

The premiere of the Third Symphony took place in Paris on May 29, 1905 under the baton of A. Nikisch. Titled “The Divine Poem,” it marks the highest flowering of the composer’s work. It reflected the brightest aspects of his talent, and the ideas that worried him were embodied. “The Divine Poem” conveys the “pre-storm” state that gripped Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. However, it is translated deeply individually, not as a feeling of an impending revolution or other upheavals and cataclysms, but as the life of the soul. Scriabin was one of those composers who did not create spontaneously, but based their work on certain ideas. His notes preserve the basic outlines of his philosophical system. “Everything that exists exists only in my mind. The world... is the process of my creativity,” the composer believed.

The third symphony is of particular interest because it seems to connect the early Scriabin with the late. It richly presents the various shades of the composer’s worldview, his entire path from “despair” to “optimism” and from disappointment in life to radiant ecstasy. For the first time, it uses the huge orchestra that would later be used in The Poem of Ecstasy and Prometheus.

Music

The first part is preceded by an introduction; at its very beginning, a Liszt theme sounds fortissimo - the octaves of bassoons, trombone, tuba and string basses intone seven chanted notes - the theme of self-affirmation, a kind of “I am.” This is the core of the entire symphony. She is answered by the sharp fanfare of three trumpets. The sonority subsides, and the arpeggi of harps and strings can be heard. They contain a number of colorful harmonic comparisons. Towards the end of the introduction there is complete calm, a transition to the first part, which has the subtitle “Struggles”.

The first part is built according to the scheme of a classical sonata allegro, but its scale is grandiose. This is achieved by expanding each of the main sections of the form - exposition, development, reprise and the large coda, which is the second development. The main theme of the movement, presented by the violins, with its melodic turns is close to the theme “I am”, but unlike that, it is powerful, affirming, uncertain, and full of anxiety. This is how Scriabin shows the splitting of the “I” into one that is confident in its strength and one that is hesitant and doubtful. This theme runs through the orchestra many times, varying and fragmenting in various ways, now growing, now subsiding, conveying a variety of emotional shades. A new phase of development begins: the flute, violin and clarinet soar bright scales, and the horns, in unison with the cellos, sing an expressive melody (“with enthusiasm and rapture” - the author’s remark). This is the first impulse towards light and joy in the symphony. It fades out quite quickly, transitioning into a restrained waltz-like theme from the violins, partly foreshadowing the thematic material of the second movement. The side part, light, capricious, flighty, is presented by woodwinds against the backdrop of graceful, sinuous melodic patterns of violins. After its brief development, the final game begins, at first restrained and calm. Its color, clear and gentle, is created by the tremolo of the strings, the light lines of the woodwinds, and the echoes of the harps. A pastoral theme appears in the flutes and violins, after which the sonority begins to increase, the melody acquires an ecstatic character, and soon the climax occurs in the tutti of the orchestra, indicated by the composer with the remark “divine, grandiose.” The fanfare rhythms of the entire orchestra sound solemnly and at the same time impetuously, and finally the motive “I am” is heard. As in the introduction, it appears twice and resolves twice into a stream of arpeggias. During development, fragments of the main batch pass through different tools, combined with the simultaneous development of a side batch. But at the moment of climax, everything seems to collapse, slide down with a rapid chromatic scale (the author’s remark is “a terrible collapse”). Gradually, more and more climaxes are prepared and collapse. The latest one in development starts from afar. After reaching the climax, the theme “I am” loudly enters, but quickly breaks off. The next passage is gloomy, alarming (“with anxiety and horror”). The reprise repeats the main contrasts and climaxes of the exposition, but the specific presentation of themes and orchestration are varied. Following the end of the reprise, another extensive coda sounds.

Critics reproached the composer for excessively expanding the movement. And indeed, the balance is upset, but this is necessary: the first part “flows” into the second without interruption. Written in a loose three-part form, it is entitled "Pleasures." The first theme of the movement is full of languor and sensual charm. The theme is widely developed: its presentation is rich in exquisite harmonic effects. The episode, equipped with the remark “with boundless rapture,” is typical of true Scriabin harmonies - the apogee of sensuality, immersion in the delights of pleasure. The harps enter for the first time, the timpani rumble dully on a bass note. A new phase begins - the clarinet appears a winding melody, akin to the future theme of the finale, but emotionally opposed to it - images of pantheism, extremely important for the concept of the symphony. The strings are accompanied by calm tremolos, the horns have sustained notes, the harp has alternating chords, and the flutes have an imitation of birdsong, which continues and even intensifies when the main theme enters again.

The finale - "The Divine Game" - is written in sonata form, more laconic than in the first movement. It begins with a trumpet fanfare, playing a melody close to the theme “I am.” The music approaches the fast march genre, but without a consistent rhythm. It is rather a dissolution of real marching into rhythms that are more capricious, vague, and unstable. The side part (flute and cellos in unison) resembles the connecting part of the first movement, but is distinguished by concentrated meditation. Its development leads to the final part, in which winding melodic moves give way to light, transparent music, full of lyrical delight. The orchestration is characteristic - tremolo of strings, arpeggios of harps, sparkles of wood, rich chords of brass, vague rumble of timpani - and above all the high sounds of a piccolo flute. The development is not large, but it energetically develops the fanfare of the theme “I am” the initial motive of the finale. Scriabin's remarks - “swiftly”, “divine”, “luminous”, “more and more sparkling” - emphasize the steady emotional growth. In the reprise, the main part is greatly reduced, the side part is expanded and contains new features, in particular, more developed fanfare themes from the second part. The final part leads to the coda. The main themes of all parts sound, and finally, for the last time, the theme “I am” is powerfully affirmed. Scriabin's self won. The long-familiar arpeggios, which invariably accompanied the theme of self-affirmation, are now full of triumph, confidence and strength. Here the final, most powerful climax is reached for the last time. The tremolo of the timpani increases. Powerful voices of copper merge into a single choir. This is the highest point of self-affirmation. This is ecstasy.

The anthem of the revolution was his Third Symphony ("Divine Poem"), the first performance of which took place in January 1905 under the baton of the Hungarian conductor Arthur Nikita. At the beginning of the 20th century. The centers of musical life in Russia were the Mariinsky and Bolshoi theaters. However, the main achievements of opera art of this time are associated with the activities of private opera in Moscow (S.I. Mamontov, and then S.I. Zimin). On the stage of the Moscow Private Russian Opera Mamontov, the talent of the outstanding Russian singer and actor F.I. Chaliapin (1873-1938) was revealed in full force. “In Russian art, Chaliapin is an era like Pushkin,” wrote Gorky. The Russian vocal school produced many wonderful singers, among whom F.I. Shalyapin, L.V. Sobinov, A.V. Nezhdanova. Complex processes took place in the visual arts. The Wanderers Association remained one of the main creative organizations of Russian artists. Many of the Itinerants experienced the influence of the revolutionary movement (N.A. Kasatkin, S.V. Ivanov, I.I. Brodsky, etc.).

|

Work |

Name in foreign language |

Opus number |

date of creation |

|

|

Waltz in f minor |

||||

|

Etude cis-minor |

||||

|

Prelude H major |

||||

|

Impromptu in the form of a mazurka in C major |

||||

|

Ten Mazurkas: |

||||

|

Allegro appassionato es-moll |

Allegro appassionato |

|||

|

Two nocturnes: |

||||

|

First Sonata in F minor |

||||

|

Two impromptu in the form of a mazurka: |

||||

|

Twelve etudes: |

||||

|

Two pieces for the left hand: · Prelude cis-minor · Nocturne Des-dur |

||||

|

Two impromptu: |

||||

|

24 preludes: |

||||

|

Two impromptu: |

||||

|

Six preludes: |

||||

|

Two impromptu: |

||||

|

Five Preludes |

||||

|

Five Preludes: |

||||

|

Seven Preludes: |

||||

|

Concert Allegro in B minor |

Allegro di concert |

|||

|

Second sonata gis minor |

Sonate-fantaisie |

|||

|

Concerto for piano and orchestra fis-moll |

||||

|

Polonaise b-moll |

||||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Third sonata fis-moll |

||||

|

"Dreams". Prelude for large orchestra e-moll |

||||

|

Nine Mazurkas |

||||

|

First Symphony in E major for large orchestra |

||||

|

Two preludes: |

||||

|

Fantasy h-moll |

||||

|

Second Symphony in C minor for large orchestra |

||||

|

Fourth sonata Fis-dur |

||||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Two poems: |

||||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Tragic poem |

||||

|

Three preludes: |

||||

|

"Satanic Poem" |

"Poeme satanique" |

|||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Waltz As major |

||||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Two mazurkas: |

||||

|

Eight etudes: |

||||

|

Third Symphony "Divine Poem" C major |

||||

|

Two poems: |

||||

|

Three plays: · Album leaf · A whimsical poem · Prelude |

Feuillette d'album Poeme fantasque |

|||

|

Scherzo in C major |

||||

|

Like a waltz |

||||

|

Four preludes: |

||||

|

Three plays: · Prelude |

||||

|

Four pieces: · Fragility · Prelude · Inspired Poem · Dance of Longing |

Danse languide |

|||

|

Three plays: · Mystery · Poem of Longing |

Poeme languide |

|||

|

Fifth Sonata |

||||

|

"Poem of Ecstasy" for large orchestra |

"Poeme d'Extase" |

|||

|

Four pieces: · Prelude |

||||

|

Two plays: · Wish · Weasel dance |

Caresse dansee |

|||

|

Album leaf |

Feuillette d'album |

|||

|

Two plays: · Prelude |

||||

|

"Prometheus, Poem of Fire" for large orchestra, piano, choir and organ |

"Promethee, le poeme du Feu" |

|||

|

Poem-nocturne |

||||

|

Sixth Sonata |

||||

|

Two poems: · Weirdness |

||||

|

Seventh Sonata |

||||

|

Three studies |

||||

|

Eighth Sonata |

||||

|

Two preludes |

||||

|

Ninth Sonata |

||||

|

Two poems |

||||

|

Tenth sonata |

||||

|

Two poems |

||||

|

Poem "To the Flame" |

||||

|

Two dances: · Fairy lights · Dark flame |

Flammes sombres |

|||

|

Five Preludes |

Works unpublished during the author's lifetime or remaining in manuscript

|

Work |

Name in foreign language |

Opus number |

date of creation |

|

|

Allegro. Overture in d minor for symphony orchestra |

Incomplete |

|||

|

Andante A major for string orchestra |

||||

|

Ballad b-minor |

Manuscript (unfinished) |

|||

|

Waltz gis-moll |

||||

|

Waltz Des major |

||||

|

Waltz-impromptu Es-dur |

Manuscript |

|||

|

Variations on the theme of Egorova f minor |

||||

|

Variations on the Russian theme "We're tired of the nights, we're bored" for string quartet |

||||

|

Canon d minor |

||||

|

A leaf from the album As-dur |

||||

|

Leaf from the Fis-dur album |

||||

|

Mazurka F major |

||||

|

Mazurka h-moll |

||||

|

Nocturne As major |

||||

|

Nocturne Des major |

Manuscript (unfinished) |

|||

|

Nocturne g-moll |

Manuscript (unfinished) |

|||

|

Romance for horn and piano |

Romance rour cors a pistons in fa |

|||

|

Scherzo in Es major |

Manuscript |

|||

|

Scherzo in F major for string orchestra |

||||

|

Scherzo As major |

Manuscript |

|||

|

Sonata cis-minor |

Manuscript (unfinished) |

|||

|

Sonata es minor |

||||

|

Sonata-fantasy gis-moll |

||||

|

Fantasia for piano and orchestra a-moll. Arrangement for two pianos |

Manuscript |

|||

|

Etude Des-dur |

Manuscript (unfinished) |

Posted on the site

Similar documents

The performing appearance of the composer A.N. Scriabin, analysis of some features of his piano technique. Scriabin the composer: periodization of creativity. The figurative and emotional spheres of Scriabin’s music and their features, the main characteristic features of his style.

master's thesis, added 08/24/2013

Distinctive features and significance of music of the early 20th century. The compositional activity of S. Rachmaninov, the original foundations of his musical style. Creative let the Russian composer and pianist A. Scriabin. A variety of musical styles by I. Stravinsky.

abstract, added 01/09/2011

Alexander Porfirievich Borodin is one of the most outstanding and versatile figures of Russian culture of the nineteenth century. The creative legacy of the great composer. Borodin's work on the Second ("Bogatyrskaya") Symphony. The programmatic nature of the work.

abstract, added 04/21/2012

The Silver Age as a period in the history of Russian culture, chronologically associated with the beginning of the 20th century. A brief biographical note from the life of Alexander Scriabin. Matching colors and tones. The revolutionary nature of the creative quest of the composer and pianist.

abstract, added 02/21/2016

The childhood years of the outstanding Russian composer Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin. First trials and victories. First love and the fight against illness. Gaining recognition in the West. The creative flowering of the great composer, author's concerts. Last years of life.

abstract, added 04/21/2012

Piano works by composer Scriabin. Musical means and techniques that determine the features of the form and figurative content of the prelude. Compositional structure of the Prelude op. 11 No. 2. The expressive role of texture, metrhythm, register and dynamics.

course work, added 10/16/2013

Creativity and biography. Three periods of creative life. Friendship with the famous conductor S. A. Koussevitzky. The work of A. N. Scriabin. A new stage of creativity. Innovation and traditions in the work of A.N. Scriabin. Tenth Sonata.

abstract, added 06/16/2007

The formation of a future composer, family, study. Kendenbil's songwriting, choral compositions. An appeal to the genre of symphonic music. Musical fairy tale "Chechen and Belekmaa" by R. Kendenbil. Cantata-oratorio genres in the composer’s work.

biography, added 06/16/2011

Biography of the Swiss-French composer and music critic Arthur Honegger: childhood, education and youth. Group "Six" and the study of periods of the composer's work. Analysis of the "Liturgical" Symphony as a work by Honegger.

course work, added 01/23/2013

History of Czech violin musical culture from its origins to the 19th century. Elements of folk music in the works of outstanding Czech composers. Biography and work of the Czech composer A. Dvorak, his works in the bow quartet genre.

Contemporaries called Alexander Scriabin a composer-philosopher. He was the first in the world to come up with the concept of light-color-sound: he visualized a melody using color. In the last years of his life, the composer dreamed of bringing to life an extraordinary performance from all types of arts - music, dance, singing, architecture, painting. The so-called “Mystery” was supposed to begin the countdown of a new ideal world. But Alexander Scriabin never had time to implement his idea.

Young musician and composer

Alexander Scriabin was born in 1872 into a noble family. His father served as a diplomat in Constantinople, so he rarely saw his son. The mother died when the child was one year old. Alexander Scriabin was raised by his grandmother and aunt, who became his first music teacher. Already at the age of five, the boy was performing simple pieces on the piano and selecting melodies he had heard once, and at eight he began composing his own music. The aunt took her nephew to the famous pianist Anton Rubinstein. He was so amazed by Scriabin's musical talent that he asked his family not to force the boy to play or compose when he did not have the desire to do so.

In 1882, according to family tradition, the young nobleman Scriabin was sent to study at the Second Moscow Cadet Corps in Lefortovo. It was there that the 11-year-old musician made his first public performance. At the same time, his debut compositional experiments took place - mainly piano miniatures. Scriabin's work at that time was influenced by his passion for Chopin; he even slept with the notes of the famous composer under his pillow.

Alexander Scriabin. Photo: radioswissclassic.ch

Nikolai Zverev and students (from left to right): S. Samuelson, L. Maksimov, S. Rachmaninov, F. Keneman, A. Scriabin, N. Chernyaev, M. Presman. Photo: scriabin.ru

In 1888, a year before graduating from the cadet corps, Alexander Scriabin became a student at the Moscow Conservatory in composition and piano. By the time he entered the Conservatory, he had written more than 70 musical compositions. The young musician was noticed by director Vasily Safonov. According to his recollections, the young man had “a special variety of sound”; he “possessed a rare and exceptional gift: his instrument breathed.” Scriabin was distinguished by a special manner of using pedals: by pressing them, he continued the sound of previous notes, which were superimposed on subsequent ones. Safonov said: "Don't look at his hands, look at his feet!".

Alexander Scriabin strived for performing excellence, so he rehearsed a lot. One day he "outplayed" his right hand. The disease turned out to be so serious that the then famous doctor Grigory Zakharyin told the young man that the arm muscles had failed forever. Vasily Safonov, having learned about his student’s illness, sent him to his dacha in Kislovodsk, where he was cured.

The senior courses in free composition were taught by professor of harmony and counterpoint Anton Arensky, who was close to lyrical chamber music. His student, Scriabin, on the contrary, did not like strict composer canons and created strange, in Arensky’s opinion, works. During the years 1885–1889, Scriabin wrote more than 50 different plays - most of them have not survived or remained in unfinished form. The creativity of the young musician even then began to break out of the narrow framework of the academic program.

Due to a creative conflict with his harmony teacher, Scriabin was left without a composer's diploma. In 1892, he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory only as a pianist in the class of Safonov. Scriabin received the Small Gold Medal, and his name was included on the marble plaque of honor at the entrance to the Small Hall of the Moscow Conservatory.

Composer of the Silver Age

Alexander Scriabin. Photo: classicalmusicnews.ru

Alexander Scriabin. Photo: scriabin.ru

The young pianist played a lot. And soon after graduating from the conservatory, his illness in his right hand worsened. To continue performing, Alexander Scriabin wrote works for the left hand - “Prelude” and “Nocturne. Opus 9." However, the illness affected his mental balance. It was then that he began to reflect on philosophical topics in his diary.

The first serious failure in life. First serious reflection: beginning of analysis. Doubt about the possibility of recovery, but the gloomiest mood. The first reflection on the value of life, on religion, on God.”

At this time, the composer wrote the First Sonata, which also reflected personal experiences. In his diary, he compared “the composition of the 1st sonata to a funeral march.” However, Scriabin did not give in to despondency: he began to follow all the doctors’ recommendations and developed his own exercises that developed his injured arm. He managed to restore the mobility of his hand, but his former virtuosity was lost. Then the pianist began to pay attention to nuance - the ability to emphasize the subtlest fleeting sounds.

In 1893, some of Scriabin's early works were published by the famous Moscow publisher Peter Yurgenson. Most of the works were musical miniatures - preludes, etudes, impromptu, nocturnes, as well as dance pieces - waltzes, mazurkas. These genres were characteristic of the work of Chopin, whom Scriabin admired. In the early 1890s, the composer also wrote the First and Second Sonatas.

In 1894, Vasily Safonov helped 22-year-old Scriabin organize an author's concert in St. Petersburg. Here the musician met the famous Russian timber merchant Mitrofan Belyaev. The entrepreneur was fond of music: he created the music publishing house “M.P. Belyaev”, established and financed the annual Glinka Prizes and organized concerts. Belyaev soon published the works of the young composer in his publishing house. Among them were etudes, impromptu, mazurkas, but mainly preludes; in total, about 50 of them were written during this period.

Since then, Belyaev has supported the musician for many years and helped him financially. The patron organized Scriabin's big tour of Europe. They wrote about the musician in the West: “an exceptional personality, a composer as excellent as a pianist, as high an intellect as a philosopher; the whole thing is an impulse and a sacred flame.” In 1898, Scriabin returned to Moscow and completed the Third Sonata, which he began writing in Paris.

In the same year, Alexander Scriabin took up teaching: he needed a stable source of income to support his family. At the age of 26, he became a professor of piano class at the Moscow Conservatory.

I don’t understand how you can write “just music” now. After all, this is so uninteresting... After all, music receives meaning and meaning when it is a link in one, unified plan, in the integrity of the worldview.

Despite being busy at the conservatory, Scriabin continued to write music: in 1900 he completed a large work for orchestra. The composer neglected musical traditions: the First Symphony has not four, as usual, but six movements, and in the last one the soloists sing with the choir. Following the First, he completed the Second Symphony, even more innovative than his previous works. Its premiere caused a mixed reaction from the music community. Composer Anatoly Lyadov wrote: “Well, what a symphony... Scriabin can safely shake hands with Richard Strauss... Lord, where did the music go... From all corners, from all the cracks, decadents are creeping in.”. Scriabin's symbolist and mystical works became a reflection of the ideas of the Silver Age in music.

“Tongues of Fire” music by Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Golovin. Portrait of Alexander Scriabin. 1915. Museum of Musical Culture named after M. I. Glinka

Alexander Scriabin. Photo: belcanto.ru

Alexander Pirogov. Portrait of Alexander Scriabin. XX century Russian Academy of Sculpture, Painting and Architecture named after I.S. Glazunov

In 1903, Scriabin began working on the score of the Third Symphony for a huge orchestra. It revealed Scriabin's skill as a playwright. The symphony, called the “Divine Poem,” described the development of the human spirit and consisted of three parts: “Struggle,” “Pleasure,” and “Divine Game.” The premiere of “The Divine Poem” took place in Paris in 1905, and a year later in St. Petersburg.

God, what kind of music was that! The symphony continually collapsed and collapsed, like a city under artillery fire, and everything was built and grew from rubble and destruction. She was completely overwhelmed by the content, insanely developed and new... The tragic power of what was being composed solemnly stuck out its tongue to everything decrepit, recognized and majestically stupid, and was bold to the point of madness, to the point of boyishness, playfully elemental and free, like a fallen angel.

Boris Pasternak

Russian musicologist Alexander Ossovsky recalled that Scriabin's symphony "produced a stunning, grandiose effect." It seemed to the listeners that the composer with this work was “heralding a new era in art.”

In 1905, Alexander Scriabin's patron, Mitrofan Belyaev, died, and the composer found himself in a difficult financial situation. However, this did not stop him from working: at this time he began to write “The Poem of Ecstasy.” The author himself said that the music was inspired by the revolution and its ideals, so he chose the call “Get up, rise up, working people!” as the epigraph of the poem.

At this time, Scriabin gave a lot of concerts and in 1906 he went on tour to America for six months. The trip turned out to be successful: the concerts were a great success. And in France in 1907, some of Scriabin’s works were performed in the cycle of “Russian Seasons” by Sergei Diaghilev. At the same time, the composer completed the “Poem of Ecstasy.”

In 1909, Alexander Scriabin returned to Russia, where real fame came to him. His works were played at the best venues in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and the composer himself went on a concert tour of the Volga cities. At the same time, he continued his musical searches, moving further and further away from traditions. He dreamed of creating a creation that would unite all types of art, and began writing the Mystery symphony, which he conceived in the early 1900s.

In 1911, Scriabin wrote one of his most famous works - the symphonic poem “Prometheus”. The composer had color hearing, giving a sense of color while performing music. He decided to translate his visual perception into a poem.

I will have light in Prometheus. I want there to be symphonies of lights. The entire hall will be in variable light. Here they flare up, these are tongues of fire, you see how there are fires here in music. After all, every sound corresponds to a color. Or rather, not the sound, but the tonality.

The composer constructed a color wheel and used it when performing the poem, and wrote the part of light in the score as a separate line - “Luce”. At that time, it was technically impossible to carry out a light-color-symphony, so the premiere took place without a light part. The production of the poem required nine rehearsals instead of the usual three. According to the memoirs of contemporaries, the famous “Promethean chord” sounded like the voice of chaos emerging from the depths. Everyone was delighted with this start. Sergei Rachmaninov asked: “How does that sound to you? It’s quite simply orchestrated.” To which Scriabin replied: “Yes, you should put something on top of the harmony itself. Harmony sounds". Prometheus was the first draft of the Mystery to use a synthesis of the arts.

Scriabin became increasingly captivated by the idea of the future “Mystery”. The composer built its contours for more than 10 years. He planned to present the mystery of an orchestra, light, aroma, colors, moving architecture, poetry and a choir of 7000 voices in a temple on the banks of the Ganges. According to Scriabin's idea, the work was supposed to unite all of humanity, give people a feeling of great brotherhood and begin the countdown for a renewed world.

The composer never managed to stage “Mystery”. Scriabin had to give concerts to earn a living. He traveled to many cities in Russia and performed abroad more than once. At the beginning of the First World War, Scriabin gave charity concerts to help the Red Cross and families affected by the war.

In 1915, Alexander Scriabin died in Moscow. The composer was buried in the cemetery of the Novodevichy Convent.

“I would like to be born as a thought, to fly around the whole world and fill the entire Universe with myself. I wish I had been born into a wonderful dream of a young life, a movement of holy inspiration, a rush of passionate feeling...”

Alexander Scriabin entered Russian music in the late 1890s and immediately declared himself as an exceptional, brightly gifted personality. A brave innovator, “a brilliant seeker of new ways,” according to N. Myaskovsky,

“with the help of a completely new, unprecedented language, he opens up before us such extraordinary... emotional perspectives, such heights of spiritual enlightenment that it grows in our eyes to a phenomenon of worldwide significance.”

Alexander Scriabin was born on January 6, 1872 into a family of Moscow intelligentsia. The parents did not have the chance to play a noticeable role in the life and upbringing of their son: three months after Sashenka’s birth, his mother died of tuberculosis, and his father, a lawyer, soon left for Constantinople. Caring for little Sasha fell entirely on his grandmothers and aunt, Lyubov Aleksandrovna Scriabin, who became his first music teacher.

Sasha’s ear for music and memory amazed those around him. From an early age, he easily reproduced a melody he heard once by ear, and picked it up on the piano or other instruments. Even without knowing sheet music, at the age of three he spent many hours at the piano, even to the point of rubbing the soles of his shoes with the pedals. “That’s how the soles burn, that’s how the soles burn,” lamented the aunt. The boy treated the piano like a living creature - before going to bed, little Sasha kissed the instrument. Anton Grigorievich Rubinstein, who once taught Scriabin's mother, who, by the way, was a brilliant pianist, was amazed by his musical abilities.

According to family tradition, 10-year-old nobleman Scriabin was sent to the 2nd Moscow Cadet Corps in Lefortovo. About a year later, Sasha’s first concert performance took place there, and his first experiences as a composer occurred at the same time. The choice of genre – piano miniatures – revealed a deep passion for Chopin’s work (the young cadet put Chopin’s notes under his pillow).

Continuing his studies in the corps, Scriabin began to study privately with the prominent Moscow teacher Nikolai Sergeevich Zverev and in music theory with Sergei Ivanovich Taneyev. In January 1888, at the age of 16, Scriabin entered the Moscow Conservatory. Here Vasily Safonov, director of the conservatory, pianist and conductor, became his teacher.

Vasily Ilyich recalled that Scriabin had

“a special variety of timbre and sound, special, unusually subtle pedaling; he had a rare, exceptional gift - his piano “breathed”...

“Don't look at his hands, look at his feet!”

- said Safonov. Very soon, Scriabin and his classmate Seryozha Rachmaninov took the position of the conservatory “stars” who showed the greatest promise.

Scriabin composed a lot during these years. In his own list of his compositions for the years 1885-1889, more than 50 different plays are named.

Due to a creative conflict with the harmony teacher, Anton Stepanovich Arensky, Scriabin was left without a composer's diploma, graduating from the Moscow Conservatory in May 1892 with a small gold medal in piano class from Vasily Ilyich Safonov.

In February 1894, he performed for the first time in St. Petersburg as a pianist performing his own works. This concert, which took place mainly thanks to the efforts of Vasily Safonov, became fateful for Scriabin. Here he met the famous musical figure Mitrofan Belyaev; this acquaintance played an important role in the initial period of the composer’s creative path.

Mitrofan Petrovich took upon himself the task of “showing Scriabin to people” - he published his works, provided financial support for many years, and in the summer of 1895 organized a large concert tour of Europe. Through Belyaev, Scriabin began relationships with Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, Lyadov and other St. Petersburg composers.

First trip abroad - Berlin, Dresden, Lucerne, Genoa, then Paris. The first reviews from French critics about the Russian composer are positive and even enthusiastic.

“He is all the impulse and the sacred flame,”

“He reveals in his playing the elusive and peculiar charm of the Slavs - the first pianists in the world,”

- write French newspapers. His individuality, exceptional subtlety, and special, “purely Slavic” charm were noted.

In subsequent years, Scriabin visited Paris several times. At the beginning of 1898, a large concert of Scriabin’s works took place, which in some respects was not quite ordinary: the composer performed together with his pianist wife Vera Ivanovna Scriabin (née Isakovich), whom he had married shortly before. Of the five sections, Scriabin himself played in three, and Vera Ivanovna played in the other two. The concert was a huge success.

In the fall of 1898, at the age of 26, Alexander Scriabin accepted an offer from the Moscow Conservatory and became one of its professors, taking over the leadership of the piano class.

At the end of the 1890s, new creative challenges forced the composer to turn to the orchestra - in the summer of 1899, Scriabin began composing the First Symphony. At the end of the century, Scriabin became a member of the Moscow Philosophical Society. Communication together with the study of special philosophical literature determined the general direction of his views.

The 19th century was ending, and with it the old way of life. Many, like the genius of that era, Alexander Blok, foresaw “unheard-of changes, unprecedented revolts” - social storms and historical upheavals that the 20th century would bring.

The advent of the Silver Age caused a feverish search for new paths and forms in art: Acmeism and Futurism in literature; cubism, abstractionism and primitivism - in painting. Some focused on the teachings brought to Russia from the East, others on mysticism, others on symbolism, and others on revolutionary romanticism... It seems that never before in one generation have so many different movements in art been born. Scriabin remained true to himself:

“Art should be festive, it should uplift, it should enchant...”

He comprehends the worldview of the Symbolists, becoming more and more firmly convinced of the magical power of music designed to save the world, and is also interested in the philosophy of Helena Blavatsky. These sentiments led him to the idea of “Mystery,” which from now on became for him the main work of his life.

“Mystery” was presented to Scriabin as a grandiose work that would unite all types of art - music, poetry, dance, architecture. However, according to his idea, this should have been not a purely artistic work, but a very special collective “great cathedral action”, in which all of humanity would take part - no more, no less.

In seven days, the period during which God created the earthly world, as a result of this action, people will have to be reincarnated into some new joyful essence, attached to eternal beauty. In this process there will be no division between performers and listeners-spectators.

Scriabin dreamed of a new synthetic genre, where “not only sounds and colors would merge, but aromas, dance movements, poetry, sunset rays and the twinkling of stars.” The idea amazed even the author himself with its grandeur. Afraid to approach him, he continued to create “ordinary” musical works.

At the end of 1901, Alexander Scriabin completed the Second Symphony. His music turned out to be so new and unusual, so daring, that the performance of the symphony in Moscow on March 21, 1903 turned into a scandal. The public's opinions were divided: one half of the hall whistled, hissed and stomped, while the other, standing near the stage, applauded loudly. “Cacophony” was the caustic word the master and teacher Anton Arensky used to describe the symphony. And other musicians found “extraordinarily wild harmonies” in the symphony.

“Well, a symphony... the devil knows what it is! Scriabin can safely shake hands with Richard Strauss. Lord, where did the music go?..”,

– Anatoly Lyadov wrote ironically in a letter to Belyaev. But having studied the music of the symphony more closely, he was able to appreciate it.

However, Scriabin was not at all embarrassed. He already felt like a messiah, a herald of a new religion. Art was such a religion for him. He believed in its transformative power, he believed in a creative person capable of creating a new, beautiful world:

“I’m going to tell them that they... don’t expect anything from life except what they can create on their own... I’m going to tell them that there’s nothing to grieve about, that there’s no loss. So that they are not afraid of despair, which alone can give rise to real triumph. Strong and mighty is he who has experienced despair and overcome it.”

Less than a year after finishing the Second Symphony, in 1903 Scriabin began composing the Third. The symphony, called “The Divine Poem,” describes the evolution of the human spirit. It was written for a huge orchestra and consists of three parts: “Struggle”, “Pleasure” and “Divine Play”. For the first time, the composer embodies the full picture of his “magical universe” in the sounds of this symphony.

Over the course of several summer months of the same 1903, Alexander Scriabin created more than 35 piano works, including his famous Fourth Piano Sonata, which conveyed the state of an uncontrollable flight to an alluring star, pouring out streams of light - so great was the experience he experienced during this time for creative upsurge.

In February 1904, Scriabin left his teaching job and went abroad for almost five years. He spent the following years in Switzerland, Italy, France, Belgium, and also toured America.

In November 1904, Scriabin completed his Third Symphony. At the same time, he reads a lot of books on philosophy and psychology, his worldview leans towards solipsism - a theory when the whole world is seen as a product of one’s own consciousness.

“I am the desire to become the truth, to identify with it. Everything else is built around this central figure...”

An important event in his personal life dates back to this time: he separated from his wife Vera Ivanovna. The final decision to leave Vera Ivanovna was made by Scriabin in January 1905, by which time they already had four children.

Scriabin's second wife was Tatyana Fedorovna Shletser, the niece of a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Tatyana Fedorovna had a musical education, and at one time even studied composition (her acquaintance with Scriabin began through classes with him in music theory).

In the summer of 1095, Scriabin and Tatiana Fedorovna moved to the Italian city of Bogliasco. At the same time, two close people of Alexander Nikolaevich die - the eldest daughter Rimma and friend Mitrofan Petrovich Belyaev. Despite the difficult moral state, lack of livelihood and debts, Scriabin writes his “Poem of Ecstasy,” a hymn to the all-conquering will of man:

“And the universe announced

With a joyful cry:

I am!"

His faith in the limitless possibilities of man as a creator reached extreme forms.

Scriabin composes a lot, it is published and performed, but still he lives on the brink of poverty. The desire to improve his material affairs again and again drives him around the cities - he tours in the USA, Paris and Brussels.

In 1909, Scriabin returned to Russia, where real fame finally came to him. His works are performed on the leading stages of both capitals. The composer goes on a concert tour of the Volga cities, at the same time he continues his musical search, moving further and further from accepted traditions.

In 1911, Scriabin completed one of the most brilliant works, which challenged the entire musical history - the symphonic poem “Prometheus”. Its premiere on March 15, 1911 became the largest event both in the life of the composer and in the musical life of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The famous Sergei Koussevitzky conducted, and the author himself was at the piano. To perform his musical extravaganza, the composer needed to expand the composition of the orchestra, include in the score a piano, a choir and a musical line indicating the color accompaniment, for which he came up with a special keyboard... It took nine rehearsals instead of the usual three. The famous “Promethean chord,” according to contemporaries, “sounded like a real voice of chaos, like some kind of single sound born from the depths.”

“Prometheus” gave rise, as contemporaries put it, “fierce disputes, ecstatic delight of some, mockery of others, and for the most part - misunderstanding and bewilderment.” In the end, however, it was a huge success: the composer was showered with flowers, and for half an hour the audience did not leave, calling the author and conductor. A week later, “Prometheus” was repeated in St. Petersburg, and then sounded in Berlin, Amsterdam, London, and New York.

Light music - that was the name of Scriabin's invention - fascinated many, new light-projection devices were designed, promising new horizons for synthetic sound-color art. But many were skeptical about Scriabin’s innovations, the same Rachmaninov, who once, while dissecting Prometheus at the piano in Scriabin’s presence, asked, not without irony, “what color is this?” Scriabin was offended...

The last two years of his life, Scriabin’s thoughts were occupied by the work “Preliminary Action”. It was supposed, based on the name, to be something like a “dress rehearsal” of “Mystery”, its, so to speak, “light” version. In the summer of 1914, the First World War broke out - in this historical event Scriabin saw, first of all, the beginning of processes that were supposed to bring the “Mystery” closer.

“But how terribly great the work is, how terribly great it is!”

– he exclaimed with concern. Perhaps he was standing on a threshold that no one had ever been able to cross...

In the first months of 1915, Scriabin gave many concerts. In February, two of his performances took place in Petrograd, which were very successful. In this regard, an additional third concert was scheduled for April 15. This concert was destined to be the last.

Returning to Moscow, Scriabin felt unwell a few days later. He developed a carbuncle on his lip. The abscess turned out to be malignant, causing general blood poisoning. The temperature has risen. Early in the morning of April 27, Alexander Nikolaevich passed away...

“How can we explain that death overtook the composer precisely at the moment when he was ready to write down the score of the “Preliminary Act” on music paper?

He did not die, he was taken from people when he began to implement his plan... Through music, Scriabin saw a lot of things that are not given to a person to know... and therefore he had to die...”

Scriabin’s student Mark Meichik wrote three days after the funeral.

“I couldn’t believe it when the news came about Scriabin’s death, it was so ridiculous, so unacceptable. Promethean fire went out again. How many times has something evil and fatal stopped the wings that had already unfolded?

But Scriabin’s “Ecstasy” will remain among the victorious achievements.”

- Nicholas Roerich.

“Scriabin, in a frenzied creative outburst, sought not a new art, not a new Culture, but a new earth and a new sky. He had a feeling of the end of the entire old world, and he wanted to create a new Cosmos.

Scriabin's musical genius is so great that in music he was able to adequately express his new, catastrophic worldview, to extract from the dark depths of existence sounds that old music had rejected. But he was not content with music and wanted to go beyond it...”

- Nikolai Berdyaev.

“He was out of this world, both as a person and as a musician. Only in moments did he see his tragedy of isolation, and when he saw it, he did not want to believe in it,”

- Leonid Sabaneev.

“There are geniuses who are genius not only in their artistic achievements, but are genius in every step they take, in their smile, in their gait, in all their personal imprinting. You look at such a person - this is a spirit, this is a being of a special face, a special dimension...”

- Konstantin Balmont.

Scriabin music pianist composer