The lyre is the history of the instrument. Lyra - information on the World History Encyclopedia portal

hurdy-gurdy folk musical instrument, which is rightfully considered the predecessor of the nykelharpa. Under the name "ogranistrum" the hurdy-gurdy appeared in Europe about a thousand years ago. Its names are also known: hurdy-gurdy(hardy-hardy) in England, vielle a roue in France, lira korbowa in Poland, niněra kolovratec in the Czech Republic. Among Belarusians, Ukrainians and Russians, the Western names for the instrument did not take root; they began to call it the snout, the lyre.

The instrument experienced an extraordinary rise about two hundred years ago in France, when professional musicians became interested in it. Many works were written specifically for the organistrum.

Now the instrument has practically disappeared from folk music, but not all musicians have consigned it to oblivion. In Belarus, the hurdy-gurdy is part of the State Orchestra and the orchestral group of the State Folk Choir of Belarus, and is used by musicians of the Pesnyary ensemble. In Russia it is played by: musician and composer Andrei Vinogradov, multi-instrumentalist Mitya Kuznetsov (“Ethno-Kuznya”), a group from Rybinsk “Raznotravie”, etc. Abroad, hardy-hardy can be heard, for example, at concerts of R. Blackmore in the project “ Blackmore's Night.

Descriptions of the hurdy-gurdy, available in our domestic instrument literature, give the most complete idea of the structure of this instrument and the methods of sound production when playing it.

Three articles about the hurdy-gurdy:

RSFSR (Instruments of the Russian People), “Lyre”, page 41

Page 41

The lyre (wheeled) is a three-stringed instrument with a deep, figure-eight-shaped wooden body. Both decks are flat, the sides are bent. Attached to the body is a short pegbox, dug out or assembled from separate boards, often ending in a curl. Inside the body, in its lower part, there is a wooden wheel (it is mounted on an axis passed through the shell and rotated by a handle), which acts as an “endless bow.” The wheel rim protrudes out through a slot in the deck. To protect it from damage, an arc-shaped fuse made of bast is installed above it. The top soundboard has resonator holes cut out in the form of brackets or “f-holes”; On it there is a longitudinally located key-nut mechanism, consisting of a box with 12-13 keys, which are narrow wooden strips with protrusions. When you press the keys, the protrusions, like the clavichord's tangents, touch the string, dividing it into two parts: the sounding part (the wheel is the protrusion) and the non-sounding part (the protrusion is the upper saddle). The protrusions are strengthened so that they can be rotated to move left and right and in this way align the scale when tuning it within a semitone.

The strings of the lyre are veined and are attached at one end to pins driven into the shell, and at the other to wooden pegs inserted into the head. The middle string runs inside the tuning box and is melodic, and the other 2 (bourdon) are located on either side of it. All 3 strings fit tightly to the wheel rim, but the bourdon strings - both or each separately - can be turned off at the request of the performer, for which they are hooked onto special protrusions.

When playing sitting, the instrument is held on the knees; when playing standing, it is hung on a belt over the shoulder, with the neck to the left and tilted, so that the keys, under the influence of their own gravity, move away from the melodic string with protrusions. Rotating the wheel with your right hand and pressing the fingers on the keys with your left hand, perform a melody; The bourdon strings sound continuously (unless they are muted). The sound of the lyre is buzzing, nasal. Its quality largely depends on the wheel: it must have precise alignment, a completely smooth rim and a well-rubbed resin (rosin). The lyre's scale is diatonic, its volume is about two octaves.

Written information about the existence of the hurdy-gurdy in Russia dates back to the 17th century. (Tales of contemporaries about Dm. the Pretender, part 5. St. Petersburg, 1834, p. 61). Perhaps it was brought here from Ukraine. Soon the lyre became quite widespread among the people, as well as in court and boyar musical life. The lyre was used mainly by wandering musicians-singers (most often walking kaliki), who sang folk songs, spiritual poems and performed dances to its accompaniment. Nowadays the lyre is rare.

Wheel lyre.

UKRAINIAN SSR, “Lyra”, pages 58-59, illust. 145148

Atlas of musical instruments of the peoples of the USSR (second edition, supplemented). Publishing house "MUSIC", Moscow, 1975. K. Vertkov, G. Blagodatov, E. Yazovitskaya.

Page 58

Lyre, relya, rylya - an instrument with a mostly figure-eight body, related to the Russian lyre and Belarusian lera (see). The lower and upper decks are flat, the sides are curved and wide. At the top there is a head with wooden pegs for tuning the strings. A box with a keyboard mechanism is mounted on the deck. Below is a friction wheel (endless bow) with a handle for rotation. In order to protect the wheel rim from damage, a lubnik is installed above it - a bast arched shield.

The lyre has 3 vein strings: a melodic string, called spivanitsa (or melody), and 2 bourdon strings - bass and pidbass (or tenor and bajork). The melodic string passes through the box, the bourdon strings pass outside it. All strings are in close contact with the rim of the wheel, which is rubbed with resin (rosin) and, when rotated, makes them sound. In order for the sound to be even, the wheel must have a smooth surface and precise alignment. The melody is played using keys inserted into the side cutouts of the box. The keys have protrusions (tangents), which, when pressed against the string, change its length, and therefore the pitch of the sound. The number of keys on different lyres ranges from 9 to 12. The scale is diatonic. Bourdon strings are tuned like this: pidbass - an octave below the melodic strings, bass - a fifth below the pidbass. At the request of the performer, one or both bourdon strings can be turned off from the game. To do this, they are pulled away from the wheel and secured to pins.

Illustration 145148

When playing, the instrument is placed on the knees with the head to the left and tilted, due to which the keys, under the influence of their own gravity, fall away from the strings. To make the instrument easier to hold, the musician puts a strap around his neck, attached to the body of the lyre. Rotating the wheel with his right hand, he presses the keys with the fingers of his left hand. The lyre sounds strong, but somewhat nasal and buzzing.

The lyre was mainly distributed among wandering professional musicians, who sang spiritual poems, everyday and especially humorous songs, and sometimes thoughts to its accompaniment. Among the lyre players there were many blind men who walked with guides from village to village, from city to city, to market squares and wedding feasts. The lyre was considered a more suitable instrument for playing at weddings than the bandura, due to its loud sound and cheerful repertoire.

In Ukraine there were special schools of lyre players with a fairly large number of students. So, for example, in the 60s. XIX century in the village Up to thirty people at a time practiced braiding (in Podil) with the lyre player M. Kolesnichenko. The eldest of them underwent practice, playing in neighboring villages at bazaars and weddings, and they gave the money and food they earned to the mentor as payment for training and maintenance, since they were completely dependent on him. Having completed his studies, the young musician took an exam on his knowledge of the repertoire and proficiency in playing the lyre. The exam took place with the participation of “grandfathers” - old experienced lyre players. To those who passed the test, the teacher gave the instrument and the so-called “vizvilka” (obviously, from the word “vizvil” - “liberation”) - the right to play independently. Initiation into lyre players was accompanied by a special ritual: the teacher hung a lyre on himself, intended as a reward for the student, the student covered it with his scroll, after which the instrument's strap was thrown from the teacher's neck to the student's neck, and the teacher dropped a coin into the resonator slot of the body - for good luck.

Page 59

The lyre workers united into groups (corporations), and each of them, headed by a tsekhmister (tsekhmeister), or nomad, had its own strictly defined territory of activity; playing in other places was prohibited. Violators of the order were subjected to severe punishment (including deprivation of the right to play), and their instrument was taken away.

Until the end of the last - beginning of this century, the lyre was so popular in Ukraine that N.V. Lysenko even suggested that it would eventually replace the bandura. However, this did not materialize: the bandura withstood the “competition” and received further development, and the lyre came to almost complete oblivion. The reason for this was the limitations of its musical, expressive and technical means and timbre specificity - nasality. But the most important reason, undoubtedly, is that during Soviet times the social environment in which the instrument existed disappeared.

During the Soviet years, the lyre was subjected to various improvements. A very original instrument was designed by I.M. Sklyar. It has 9 strings tuned to minor thirds and a button accordion type keyboard mechanism, thanks to which an accordion player can quickly and easily learn to play it. The wooden wheel has been replaced with a plastic transmission belt, providing a smoother sound. Using a special device, the degree of pressure of the tape on the string can be changed, thereby achieving a change in the sound strength of the instrument. Improved lyres occasionally find use in ensembles and orchestras of folk instruments.

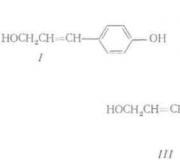

Structure and scale of the lyre: (see original article)

V. FRICTION: “Lyra”, pages 95-96

Russian folk musical instruments. Publishing house "MUSIC", Leningrad branch, 1975. K. Vertkov.

Pages 9596

Lyra or hurdy-gurdy - a friction instrument consisting of an eight-shaped resonator body, a box with keys, a peg box with transverse wooden pegs, a friction wooden wheel with a handle for rotation and three vein strings. One string runs inside the keyboard box, the other two strings extend outside it on both sides. All the strings are in close contact with the wheel and when it rotates, they vibrate due to friction and begin to sound. For better adhesion of the wheel to the strings, it is lubricated with resin (rosin). The middle string is the melodic string. Changing the pitch of the sound on it is done using keys inserted into the box along the right side. The keys, when pushed inward, press the protrusions onto the string and shorten it. The remaining two strings produce bourdon sounds that do not change in pitch.

Before playing, the performer throws a strap attached to the body over his shoulders, places the instrument on his knees, with the peg box to the left and tilted away from himself, so that the free keys fall away from the string under their own weight. With his right hand, he rotates the wheel evenly, but not quickly, by the handle, and presses the keys with the fingers of his left hand. The nature of playing the lyre is similar to playing the bagpipes and whistle; all three have continuously sounding bourdons. The sound quality largely depends on the friction wheel: it must have precise alignment, a smooth smooth surface and good lubrication with resin, otherwise the sounds will “float” and “howl”.

The position of the lyre in Russian folk instrumental music is very uncertain. Written monuments of past Centuries keep complete Silence about it. A well-known exception is the dictionaries of the 16th-17th centuries. Thus, in the “Book of the Verb Alphabet of Foreign Speeches” of 1596, the term “kinir” is explained by the word “lyri”. However, whether in this case this name should really be understood as lyre or lyrya is difficult to say, since in the “Slavic Russian Lexicon” by P. Berynda, the first edition of which was published in 1627, the same term “kinira” is interpreted as “cytara” or “ garfa" (“on garfa bryankayuchi”), that is, classified as plucked string instruments. At the same time, in the “Alphabet of Foreign Speeches” of the late 17th century there is the term “lyre”, explained in both cases as “violin” - here there is reason to see a wheeled lyre, and not an ancient plucked lyre (M. 253).

To date, no image of the Russian hurdy-gurdy has been discovered. True, in D. Rovinsky’s “Russian Folk Pictures” there are popular prints with lyre musicians, but these popular prints are copies of foreign originals and the lyres depicted on them are of a typically French type 1 . There is absolutely no mention of the lyre in Russian folklore - epics, songs, fairy tales, proverbs, etc. Russian memoirists, ethnographers and musicologists of the late 18th - first half of the 19th centuries do not write about it - Tuchkov, Tereshchenko, Snegirev, Rezvoy, etc. ., as well as foreign authors of that time (including M. Guthrie), with the exception of S. Maskevich (M. 273), I. Georgi and J. Shtelin. From the materials of the latter one can judge the structure of the lyre. Comparing it with a whistle, he writes: the bourdon strings of the whistle sound just as strong, “creaky and intrusive as on a lyre” (M. 275). Since the bourdon accompaniment on the whistle and bagpipes was monophonic, it can be assumed that the two bourdon strings were probably tuned here in the same way, either in unison, or like a whistle in an octave. It seems that the words of S. Maskevich that the lyre is “played and chanted on only one note” can be interpreted as an indication of a monophonic bourdon. This is what distinguished the structure of the Russian lyre from similar instruments of other peoples and, in particular, the Ukrainian reli and the Belarusian lera with their fifth bourdon.

1 See, for example, D. Rovinsky. Russian folk pictures. Atlas, vol. 1, l. 101.

The music of past centuries is not broadcast by modern radio stations, but lives in ancient books and museums. They are no longer played, but some people still remember musical instruments forgotten by civilization.

We all know what a piano, grand piano, trumpet, violin, guitar and drum look and sound like. What did their “grandmothers” and “grandfathers” look and sound like? We won’t be able to reproduce the sounds of an ancient orchestra, but we will tell you about ancient musical instruments.

1. Lyre

Back in Ancient Greece, musical instruments were created, which over time acquired a classic appearance and became the basis for the creation of new modern types. The lyre is the most popular musical instrument during the development of the Ancient Greek state. The first mention of the lyre dates back to 1400. BC e. This instrument has always been identified with Apollo, since Hermes gave him the first lyre. And it sounded, accompanying beautiful poems. The lyre is not played today, but the term "lyric" has immortalized the instrument.

2. Kifara

It is rightfully considered one of the first string instruments and is a direct descendant of the lyre. Musicians holding a cithara in their hands were depicted on ancient coins, frescoes, clay amphorae and paintings. This instrument was very popular in Persia, India and Rome. Unfortunately, it is impossible today to accurately reproduce the sound of the cithara, but thanks to a literary description it was possible to reconstruct it.

3. Zither

This plucked string musical instrument became most widespread in Austria and Germany in the 18th century. It appeared in Russia in the second half of the 19th century. Similar instruments were found among the peoples of China and the Middle East.

4. Harpsichord

A plucked keyboard musical instrument that gained immense popularity in the Middle Ages. The first information about the harpsichord dates back to 1511. A unique instrument made in Italy in 1521 has survived to this day. Externally, the harpsichords were finished very elegantly. Their body was decorated with drawings, inlays and carvings. However, by the end of the 18th century, the harpsichord was replaced by the piano; it was supplanted and completely forgotten in the 19th century.

5. Clavichord

One of the oldest stringed percussion-clamped musical instruments. Outwardly it was very similar to a harpsichord, but had a more powerful sound. The clavichord, created in 1543, is today housed in the Museum of Musical Instruments in Leipzig, Germany. The greatest composers Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven created many works specifically written for the clavichord.

6. Harmonium

This wind reed keyboard musical instrument was very popular at the end of the 19th century. In everyday life it was called the “organ”. The creator of the harmonium is a Frenchman named Deben, who received a patent for the manufacture of the instrument in 1840. Today the harmonium can only be seen in museums.

7. Beat

An ancient Slavic percussion instrument. It was made of iron, which was struck with a mallet. Bilo also played the role of a church bell and signaling instrument for the Old Believers.

8. Horn

The main instrument of Russian buffoons of the early Middle Ages. Outwardly it was very similar to a violin and was considered its Slavic prototype. Gudok is a pear-shaped wooden bowed instrument with three strings.

9. Hurdy Wheel

This keyboard musical instrument appeared in Central Europe in the 10th-11th centuries. Originally, the hurdy-gurdy required two people to play because the keys were on top. One turned the knob, and the second played a melody. Later the keys were placed at the bottom. In Russia, the first hurdy-gurdy appeared in the 17th century. People playing this instrument performed spiritual verses and biblical parables.

10. Kobza

Ukrainian national plucked string musical instrument. It is believed that the kobza was brought to Ukraine by Turkic tribes, but the instrument acquired its final appearance in these lands. The image of the kobzar, who accompanied his songs and thoughts by playing the kobza, was immortalized in his work by T. Shevchenko. The kobza was a favorite instrument of Ukrainian Cossacks and villagers, but after 1850 it was replaced by the bandura.

11. Rainstick

The rain flute is an exotic ancient musical instrument that was used by shamans of South and North America to control the rain element. It perfectly imitated the sound of water pouring or falling rain. Previously it served as a cult instrument in the ancient rites of local aborigines. Today, rhinestone acts as a talisman for housing against envy and malice.

12. Kalimba

The oldest musical instrument of African tribes. Today in parts of Central and Southern Africa it is used in traditional ceremonies. The Kalimba is called the "African hand piano".

This instrument was known in the 16th century. under another name – zinc, the same “great-grandfather” of wind instruments. It was invented by the Frenchman Edme Guillaume. A serpent is a curved tube that looks very much like a snake. The instrument was made from wood or bone, covering the base with tanned leather. Sometimes the tip of the serpentine was made in the form of a reptile's head.

In 1752, an instrument was invented in St. Petersburg that replaced an entire orchestra, which consisted of 40-80 hunting horns, each of which was carefully processed and tuned to its own unique sound. It is clear that size mattered here: the largest horn sounded low, and the smallest produced high notes.

15. Ionic

Until recently, this musical instrument was an integral part of any vocal and instrumental ensemble. Ionica is a trademark of electric musical instruments produced in the German Democratic Republic in 1959. In the Soviet Union, the term “ionics” began to be used in relation to all small-sized keyboard instruments. Over time, it was replaced by transistor devices, which were more reliable.

Turkey is a country in western Asia and partly in the extreme southeast of Europe. The Asian part of Turkey is called Anatolia, the European part is called Eastern Thrace. Area 767.1 thousand square meters. km. Population 76,256 thousand people. Capital Ankara. Since October 1923 - a republic. The country's main source of income is tourism. Due to this, dollars and euros are in circulation.

The Turkish lira is the official currency of Turkey. It also serves as the official currency of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, recognized exclusively by Turkey. Historically, the name “lyre” comes from the Latin word Libra, translated as “scales”, and later used to designate a measure of the weight of silver in the calculations of merchants - the so-called troy pound.

1 lira is equal to 100 kurus. Denominations of current banknotes: 200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5 liras. Coins: 1 lira, 50, 25, 10, 5, 2 and 1 kurus. The ISO code of the Turkish Lira is 4217, the official abbreviation is TRY, but in everyday life the previous abbreviation is often used - YTL (from the abbreviation Yeni Turk Liras, which translates as “New Turkish Lira”).

The Central Bank of Turkey has the right to issue. Turkey currently uses a floating exchange rate regime. The criterion for the effectiveness of exchange rate policy (exchange rate anchor) is inflation indicators. The Turkish lira has an unstable exchange rate in relation to other currencies of the world.

In March 2012, the Turkish lira received a graphic symbol, which passed a strict selection among 8 thousand options submitted to an open competition. According to the authors, the symbol of the national Turkish currency will help increase recognition and strengthen the lira. It represents an anchor-like double-crossed letter that is a cross between a t and an l.

Turkish money is a means of payment and also performs many other functions.

HISTORY OF THE TURKISH LIRA

The history of Turkish currency goes back to the times of the Ottoman Empire, which existed from 1299 to the end of the 19th century. Precious metals were widely used as money. Ancient coins were issued by the sultans and bore their names, but not their portraits, in accordance with Islamic tradition.

In 1327, Orhan minted akche (“whitish”). This small silver coin was in circulation in the territory of the Ottoman Empire and its neighboring states in the 14th - 19th centuries.

The first gold coin (zekhin) in the Ottoman Empire was the sultani or altun. It began to be minted under Suleiman I the Magnificent in 1454 after the conquest of Constantinople.

From 1623 until 1930, a Turkish silver coin, a pair, was also in circulation. Then it was used exclusively as a counting unit, 1/40 kurush. The kurush is a small Turkish coin used in the Ottoman Empire since 1688.

The Turkish lira first became an official currency in the Ottoman Empire in 1844. It replaced the previous currency, the kura, which was not withdrawn from circulation, but was used to exchange liras. At that time, 1 lira was worth 100 kuru.

In 1844-1881, the Turkish lira was created on the basis of bimetallism (metallic monetary systems built on a fixed ratio of the value of silver to gold). One lira was worth 6.61519 grams of pure gold or 99.8292 grams of pure silver. In 1881, a standard based on gold was adopted, and during the First World War, the lira “severed its relationship” with the value of precious metals.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, 9 series of banknotes have been issued in Turkey. At the end of the 20th century, during the action of the 7th series, the Turkish lira was considered an unstable currency, its exchange rate changed almost every day, and banknote denominations reached 20,000,000 liras.

At the end of December 2003, the National Assembly of the country adopted a law according to which 6 zeros of the currency were eliminated and a new Turkish lira was formed. On January 1, 2005, the "new Turkish lira" series 8 was introduced into circulation, replacing the previous lira at the rate of 1 new lira = 1,000,000 old lira.

The next, series 9, was released on January 1, 2009, and series 8 banknotes ceased to be valid after December 31, 2009 (although they can be freely exchanged at the Central Bank until December 31, 2019). Series 9 banknotes have the inscription "Turkish lira" without the word "new" as in series 8.

TURKISH LIRA BANKNOTES

Banknotes in denominations are 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 liras. On the front side of all Turkish banknotes there is a portrait of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first president of Turkey, under whose leadership the power of the Sultan was abolished and a republic was proclaimed.

5 Turkish lira. Size 64x130 mm. Brown color.

The reverse side depicts a portrait of the outstanding Turkish historian Aydin Sayili (Ayd n SAYILI), a fragment of the solar system, the structure of an atom and a fragment of a DNA chain.

10 Turkish lira. Size 64x136 mm. The color is red.

The front side depicts a portrait of Ataturk.

On the reverse side there is a portrait of the mathematician Cahit Arf and his formula for the Arf invariant of quadratic form.

20 Turkish lira. Size 68x142 mm. Green color.

The front side depicts a portrait of Ataturk.

The reverse side depicts a portrait of the outstanding Turkish architect Mimar Kemaleddin, the building of Gazi University, an aqueduct, geometric figures: cube, sphere, cylinder.

50 Turkish lira. Size 68x148 mm. Orange color.

The front side depicts a portrait of Ataturk.

On the reverse side there is a portrait of the Turkish writer Fatma Aliye Han m, a stack of papers, an inkwell with a pen, and books.

The first woman to appear on a Turkish banknote.

100 Turkish lira. Size 72x154 mm. Color blue.

The front side depicts a portrait of Ataturk.

The reverse side depicts a portrait of the Turkish musician Buhurizade Itri, a seated figure of Rumi, musical instruments, and musical notes.

200 Turkish lira. Size 72x160 mm. The color is lilac.

The front side depicts a portrait of Ataturk.

The reverse side depicts: a portrait of the Turkish poet Yunus Emre, who died in 1321, his mausoleum, flying doves, roses.

The larger the bill, the earlier the historical figure depicted on it lived. 200 lira is the largest banknote in Turkey.

In addition to the Turkish lira, US dollars, euros and pounds sterling are in use in the country, which are accepted for payment in shops, restaurants and hotels in large cities and resorts. However, it is difficult to pay in foreign currency in the province.

The Turkish lira is protected from counterfeiting in many ways. Each banknote has a watermark, a holographic stripe that changes color. The denomination number is stamped in the right corner of the banknote, which can be tested by touch, allowing recognition of the denomination by touch. Turkish banknotes use multi-level security systems. This makes them one of the most technologically advanced banknotes in the Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Due to the rapid deterioration of Turkish lira, the question arose about introducing plastic banknotes into circulation. In terms of wear and tear, plastic banknotes are five times more efficient than paper ones, which significantly extends their service life. Today, many countries have successfully used plastic money in circulation. They cost 50% more than their predecessors, but in terms of wear and tear they are five times more durable than paper ones. The advantages of plastic banknotes over paper ones are obvious: they do not get wet, do not wear out, and most importantly, they cannot be counterfeited.

COINS

New coins were issued in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 kurus and 1 lira. A portrait of Ataturk is printed on the obverse of Turkish coins, and the denomination, ornament and year of minting are printed on the reverse. The only exception is the 50 kurus coin: it features the suspension bridge, a landmark of Istanbul.

1 Turkish lira. Bimetal: ring – brass (Cu 79%, Ni 4%, Zn 17%), insert – copper-nickel-zinc alloy (Cu 65%, Ni 18%, Zn 17%). Diameter 26.15 mm, thickness 1.90 mm, weight 8.20 grams. The edge is corrugated. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

Obverse: in the center, in a circle, to the left is the head of Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) (1881 - 1938), Ottoman and Turkish politician, statesman and military leader, founder and first leader of the Republican People's Party of Turkey; first President of the Turkish Republic from October 29, 1923 to November 10, 1938. Under the portrait there is a dot, along the edge of the coin there is a circular inscription: TURKIYE CUMHURIYETI.

Reverse: in the center - the denomination in two lines against the background of the ornament: 1 TURK LIRASI. At the top of the coin is a crescent with a star, at the bottom is the year of issue.

50 kurus. Bimetal: ring – copper-nickel-zinc alloy (Cu 65%, Ni 18%, Zn 17%), insert – brass (Cu 79%, Ni 4%, Zn 17%). Diameter 23.85 mm, thickness 1.90 mm, weight 6.80 grams. The edge is corrugated. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

Obverse: in the center, in a circle, to the left is the head of Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk). Under the portrait there is a dot, along the edge of the coin there is a circular inscription: TURKIYE CUMHURIYETI.

Reverse: in the center – denomination in two lines: 50 KURUS. against the backdrop of the “Ataturk Bridge” connecting the European and Asian parts of Turkey, which are symbolically depicted at the bottom of the coin. At the top of the coin is a crescent moon with a star, at the bottom is the year of issue.

25 kurus. Diameter 20.5 mm, thickness 1.65 mm, weight 4 grams, composition: 65% copper, 18% nickel and 17% zinc, ribbed edge. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

10 kurus. Diameter 18.5 mm, thickness 1.65 mm, weight 3.15 grams, composition 65% copper, 18% nickel and 17% zinc, smooth edge. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

Obverse: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Reverse: denomination, pattern, year of minting.

5 kurus. Diameter 17.5 mm, thickness 1.65 mm, weight 2.9 grams, composition: 65% copper, 18% nickel and 17% zinc, smooth edge. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

Obverse: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Reverse: denomination, pattern, year of minting.

1 kurush. Diameter 16.5 mm, thickness 1.35 mm, weight 2.2 grams, composition: 70% copper and 30% zinc, smooth edge. The coin was put into circulation on January 1, 2009.

Obverse: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Reverse: denomination, pattern, year of minting.

Note to tourists

In tourist places, both dollars and euros are accepted, but it is better to have Turkish lira with you. You can exchange currency in banks, exchange offices, hotels, and post offices. The rate at banks is not the most favorable, but only they provide confirmation of the exchange, on the basis of which unused Turkish lira can be exchanged. It is often more attractive at exchange offices, although there is a possibility of encountering unpleasant surprises. The most attractive rate is usually observed in post offices (yellow sign with the inscription "PTT").

Under no circumstances should you trust hotel and transfer guides who say that they have the best rates and that you will certainly be deceived in other places. It is strictly not recommended to change money by hand! Moreover, the exchange rate on the “black market” is not very different.

It is best to carry money partly in cash and partly on a card. Cash may be required at passport control. In Turkey, no one has repealed the law requiring those entering the country to have a proof of arrival (tourist voucher, tour package, invitation to an event) and cash at the rate of $50 per day. They are asked to present them very rarely, but no one is immune from this. In this case, a plastic card will not be an argument, even if there is a very large amount on it.

It is better not to take VISA Electron, Maestro and American Express cards, as some ATMs simply do not take them seriously and often delay them. Classic VISA and Master Card are accepted absolutely everywhere and are serviced by all ATMs. Better take a ruble card.

In Turkey, small bills are considered popular. If you pay with a 200 lira bill at lunch, you will have to wait until the evening for change. Therefore, try to exchange money with change, that is, so that you have as many small bills as possible in denominations of 5, 10 and 20 Turkish lira. The concept of change from 1 dollar or euro does not exist.

In the shops of traders in numerous bazaars, sometimes there is no difference in currency at all. That is, the product costs roughly 50... and it doesn’t matter what: liras, dollars or euros. Therefore, having Turkish lira in your pocket is not only convenient, but also profitable. In the markets you should bargain for every lira. If a compromise on price is not reached, you can leave calmly, but always with a smile.

Many goods are cheaper in Turkey than in Russia. For example, jewelry, wardrobe items, accessories, household appliances. It is not surprising, since many of these goods are brought to Russian cities from Turkey. Transport costs and price increases by resellers lead to higher prices. Therefore, shopping in Turkey is considered not only exciting, but also profitable.

lyra) is an ancient plucked string instrument (chordophone).The body (resonator) of a round or quadrangular shape (among the Greeks and Romans - only round) is connected to the crossbar (transverse rod) by two handles. Strings (made from sheep intestines) of equal length are stretched between the body and the crossbar.

The technique of playing all ancient lyres is the same: the musician held the instrument at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the body, playing standing (especially the lyre) or sitting. The sound was produced by a bone plectrum. The fingers of his free hand muffled the unnecessary strings. There was no gender difference among lyre players, with the exception of the lyre, which was a male instrument. Learning to play the lyre was part of the basic education of a free citizen in Ancient Greece and Rome.

Accompanied by the lyre, poems were sung solo and by a choir (more precisely, by a vocal ensemble); hence the whole genus of ancient poetry received the name “lyric”, or lyricism.

Functional Descriptions varieties lyres in ancient literature are difficult to unify. Helis (apparently due to its light weight and simplicity of design) was considered a teaching and home instrument. The larger barbite (especially in late antique texts) was described as a favorite instrument of the lesbian poet-musicians Terpandra, Sappho and Alcaeus. The kithara is usually presented as an instrument for professionals, participants in public competitions (in modern terms, international string competitions). The forminga, judging by literary descriptions (Homer, Pindar, Bacchylides, Homeric Hymns) and archaic and classical depictions, was an instrument functionally identical to the cithara; in later times, images and mentions of formings in Greek literature almost completely disappear (for this reason, in the Latin musical treatises of the Middle Ages there is no corresponding term for formings), apparently due to the development and widespread distribution of the cithara.

Corpus (re-zo-na-tor) of a round or 4-gonal shape is united with a re-cla-di-noy (in trans-speech) Noah shtan-goy) with two hands. The strings are of the same length, between the core and the cross.

In-st-ru-men-you of the Lyra-type were ras-pro-country in most of the c-vi-li-za-tions of the Ancient world . The most ancient Lyres go back to the cult-tu-re of Shu-mera (the earliest images are from-tis-ki pe-cha-tey on the ob- breaking clay tablets, around 2650 BC). Valuable archaeological finds - in-st-ru-men from the royal tombs of Ur (about 2450 BC), the largest among them is the “golden li-ra” (height 120 cm, length of the cross-bar 140 cm), decorated with sacred head puppy; “silver lyre” with traces of 11 strings (i.e. there were 11 strings) and a ro-o-r-az-no-th raz-po-lo-zhe-niya strings. On the territory of the 3-2nd millennium BC. e. Su-merian images of a new version of Lyra appeared - go-ri-zon-tal. In the Middle River of Lyra there were races before the era of el-li-niz-ma. In the visual arts of Ancient Egypt from the 15th century BC. e. Lyres of the shu-mer type are found, the first known image is in the Russian tombs of no-mar- ha Khnum-ho-te-pa II (ru-bezh XX/XIX centuries BC) in Be-ni-Ha-sa-ne. A large multi-stringed Lyre with a rectangular body depicted on the wall of the Temple of Amo-na-Ra in Karnak (XVI- XII century BC). Lyra fi-gu-ri-ru-et in To-re under the name “kin-nor”, which in Vul-ga-te pe-re-ve-de-no as “li-ra”.

Numerous depictions of the ancient Greek Lyra (the earliest ones date back to the end of the 8th century BC; sculptural figures gourds made of lead, found in Sparta, 7th century BC). The fragments of the Lyra-he-lis (ancient Greek χέλυς - che-re-pa-ha) were preserved - my little one from the family of the ancient Greek Lyra, with kor-pu-som from pan-tsi-rya che-re-pa-hi, about-cha-well-to-go-catch-her skin. In Ancient Greece, the word “Lyre” was used to denote any in-st-ru-men-ta of a family. va lir (bar-bit, ki-fa-ra, for-min-ga, he-lis), in a narrow sense - for he-lis. The word “Lyre” is first found in Ar-hi-lo-ha (mid-7th century BC). Is-to-ria "about-re-te-niya" in-st-ru-men-ta (with the participation of Her-mes, He-rak-la, Or-fairy, Ta-mi- ria, Am-fion-na and other mythical per-so-na-zhey) from-no-si-tel-but late: for-pi-sa-na in the 2nd century AD. e. No-ko-ma-hom, but around 500 AD. e. ras-shi-re-na Bo-etsi-em. He-lis and for-min-ga - the most ar-ha-ichic variety of the an-tic Lyra He-lis was used mainly in educational purposes. For-min-ga (φόρμιγξ; first mentioned in “Ilia-da”, then more than once in Pin-da-ra) - inst. -ru-ment of a larger size with a round wooden body and straight handles. Bar-bit (βάρbiτον, βάρβιτος) is close in design to he-li-su, but with a larger body and long handles, away from the body at a sharper angle. The building height of the bar-bi-ta is lower than that of the he-li-sa; ha-rak-ter-but its use in the cult of Dio-ni-sa. The largest in size and the most developed in-st-ru-ment of the family - ki-fa-ra; used for ac-com-pa-not-men-ta pen-nu and (from the 4th century BC) for self-standing professional mu- zi-tsi-ro-va-niya. Technical games on all the ancient Lears are about the same; the musician held the instrument at an angle of about 45° from himself, played standing or sitting; sound from a bone plectrum. There is no gender difference among the uses on Lyra, except for the key -fa-ry, which was a man's in-st-ru-men. The classic 7-string Lyre is considered; she was seen as a reflection of the world's gar-mo-nii (according to Vergilia's saying: septem discri-mi- na vo-cum - “seven [high-pitched] different sounds”; “Aeneid”, VI 646).

The strings of the Lyra gave the names of the steps of the Greek full-sound; in essence, the names of the strings denote the mod-distant functions of the star-rin-no-go la-da (see the articles of the So-ver-shen-naya system te-ma, Mo-distance). The number of strings of the Lyra could be increased to 18, but more often than not, experimental instru-men describe how 11-12 strings. “Much-flowing” (πολυχορδία) refers to the disturbing soul “many-sounding” (πολυφωνία; this word is not about -knows a lot of things) and in some way rated it as harmful from the December 5th century BC, published in the book “Essentials of Music” by Boetius). Although many tracts describe the ancient Greek sound as a co-response to the flowing string of the Lyra, precise information about her on -no construction. Learning to play the Lyra in classical Greece was a basic part of the education of citizenship. In agreement with the wide-spread-country-presentation of the ancient Greek phil-lo-so-fs (see, for example, in “Go-su-dar-st -ve" and "Pro-ta-go-re" Pla-to-na), ki-fa-ra for-nima-la the highest position in this-che-skaya i-rar- hii of musical in-st-ru-men-tov, for (in combination with me-li-che-skaya in ezi-ey, la-dom and rhythm) she re-pi-you -va-la in the boys there is blissful restraint and ras-su-di-tel-ness, the de-la-la of their souls and thoughts are gar-mo- nothing. Lyra was used in different ways: at weddings and feasts (especially on sim-si-yahs), holidays in honor of military victories, in tser-re-mo-ni-al-nyh (as a rule, not associated with mourning) processes, in those at-re and by-tu for co-pro-vo-zh-de-niya singing and dance. In the classical era, you-stu-p-le-nia and competition of ki-fa-reds and ki-fa-rists were an obligatory part sports competitions and general Greek festivals (games) in honor of the gods. Lyra is at-ri-but Apol-lo-na, with her also as-so-tion-ru-yut-sya Her-mes, muses, Kas-tor and Pol-lux, Pa-ris, Eros . Well-known musicians entered history: Ter-pandr, Pin-dar, Ti-mo-fey Mi-let-sky, Stra-to-nik Athens skiy and others

In the 2nd century BC. e. The lyre was brought from Ancient Greece to Ancient Rome. From the West in Ancient Iran [for example, Shah Wah-ram V Gur (5th century AD) kept at court a performer on the Greek Lyre, which -then-paradise about-at-the-cha-las-by-the-term “ka-nor”, found in the memory of the so-called. infantry literature], Ancient Ar-menia, ancient states of Central Asia.

Liras are still not widespread in a number of countries in Africa and Asia Minor. For professional music on-ro-da am-ha-ra in Su-da-ne and Ethiopia ha-rak-ter-ny Lyra with a rectangular body (8 -9-string be-gen-na) and round-lym (6-string ky-rar, 5-string dita from pan-tsi-rya che-re-pa-hi), 4 -6-string Lyres of the archaic type are found in Ke-nia, Ugan-de, An-go-le, Ma-li and other countries.

The Lyra type also belongs to the same group of plucked and bowed instruments of Northern and Western Europe: mouth , kro-ta, jouhik-ko (Finnish), hii-u-kan-nel (Estonian), etc. The earliest arch-heo-logical discoveries da-ti-ru-yut -Xia V-VIII centuries (England); single-st-ven-ny ek-zem-p-lyar according to the in-st-ru-men-ta, from-to-sya-sya to the culture of Ancient Ru -si, - so-called gus-li with a playing window (known as “gus-li Slo-vi-sha”; Velikiy Novgorod, 11th century). In the traditional culture of the countries of Scandi-na-vii and Pri-bal-ti-ki, such in-st-ru-men met before the beginning of the 20th century.

The word “Lyra” is traditionally applied to in-st-ru-men of other types. In Italy of the 15th - early 17th centuries, there was a su-sche-st-vo-va-la li-ra and brach-cho (pre-she-st-ven-ni-tsa vik-ki). In the countries of Southern Europe, folk-lore bows are still not-visible in-st-ru-men: Greek ly- ra, Serbian and Croatian li-ri-tsa. Under the name of a wheeled ly-ra from-weight-ten stringed mechanical in-st-ru-ment.