The originality of rethinking traditional structures in the dramaturgy of E. Schwartz

I.L. Tarangula

The article highlights the forms of interaction between traditional plot-like material and the original author’s re-interpretation. The research is carried out on the materials of E.’s creativity. Schwartz ("The Naked King") and the literary decline of G.-H. Andersen. The problems of genre transformation of the followed work are examined. It is concluded that as a result of the interaction of both plots, in a universal context, the problems of dramatic processes of the era of the 30-40s are raised on par with the subtext. XX century

Key words: drama, traditional plots and images, genre transformation, subtext.

The article covers the problem of the forms of interaction of traditional plots and images and their author's original reinterpretation. The author investigated Eu. Shwarts's work "The Naked King" and H. Ch. Andersen literary heritage. The article focuses on genre transformations and the author considers the thought that as a result of plots interaction in the universal context on the sub-text level various questions of the dramatic processes of the period 1930-1940 have been raised.

Key words: traditional plots and images, genre transformations, drama.

In the literature of the twentieth century, replete with turning point historical cataclysms, the problem of moral self-esteem of the individual, the choice of a hero placed in an extreme situation, is actualized. To understand this problem, writers turn to the cultural heritage of the past, to classical examples containing universal moral guidelines. By transforming the cultural heritage of other peoples, writers strive through the prism of understanding the causes of the tragic processes of modernity to feel the deep connections of eras remote from each other.

The appeal to centuries-old cultural traditions provoked the appearance in Russian drama of the twentieth century of many works that significantly transform well-known plots and are updated with new problems (G. Gorin “That Same Munchausen”, “The Plague on Both Your Houses”; S. Aleshin “Mephistopheles”, “ Then in Seville"; V. Voinovich "Again about the Naked King"; E. Radzinsky "Continuation of Don Juan"; B. Akunin "Hamlet. Version"; A. Volodin "Dulcinea of Toboso"; L. Razumovskaya "My Sister the Little Mermaid", "Medea"; L. Filatov "Lysistrata", "Hamlet", "The New Decameron, or Tales of the Plague City", "Once More About the Naked King", etc.).

One of the writers who created original versions of traditional plot-shaped material was E. Schwartz ("The Shadow", "An Ordinary Miracle", "The Naked King", "Little Red Riding Hood", "The Snow Queen", "Cinderella", etc.).

The playwright argued that “every writer who is passionate about fairy tales has the opportunity either to go into the archaic, to the origins of fairy tales, or to bring the fairy tale to our days.” It seems that this phrase quite succinctly formulates the main ways of rethinking traditional fairy-tale structures in national literatures, which have not lost their formal and content significance in modern literature. Understanding his contemporary reality, E. Schwartz sought support for rejecting her existential hopelessness in universal humanistic codes created and interpreted by folk poetry. That is why he turns to the genre of fairy tales, which provided a wide scope for analyzing the tragic contradictions of the era.

All the most significant fairy tales and plays by E. Schwartz are “twice literary fairy tales.” The playwright, as a rule, uses fairy tales that have already been processed by literature (Andersen, Chamisso, Hoffmann, etc.). “Someone else’s plot seemed to enter my blood and flesh, I recreated it and only then released it into the world.” Schwartz took these words of the Danish writer as the epigraph to his “Shadow” - a play in which Andersen’s plot is reworked. This is exactly how both writers declared the peculiarity of their work: the creation of independent, original works based on borrowed plots.

At the heart of Schwartz's play is a conflict that is traditional for the genre of romantic fairy tales and characteristic of many of Andersen's works. This is a conflict between a fairytale dream and everyday reality. But the fairy-tale world and reality in the play by the Russian playwright are fundamentally special, since their formal meaningful interaction is carried out taking into account the multi-layered genre of the play, which is complicated by the “provocative” associative-symbolic subtext.

Based on the philosophical orientation of Schwartz's plays, researchers classify his works as the genre of intellectual drama, highlighting the following distinctive features: 1) philosophical analysis of the state of the world; 2) increasing the role of the subjective principle; 3) attraction to convention; 4) artistic proof of the idea, appealing not so much to feelings, but to reason. The combination in the play of the genre features of a magical folk tale, the artistic forms of a romantic fairy tale and the principles of artistic modeling of the world in intellectual drama provokes a genre synthesis in which the fairy tale and reality, the conventional world and modernity come as close as possible. Through such a synthesis, those moral values that help an individual (hero) survive the tragic circumstances of modern reality are “isolated” from the fairy tale. Thanks to the fairytale conventions of depicting reality, the world of “The Naked King” turns out to be quite real at the same time.

According to M.N. Lipovetsky, “passing through literature, a fairy tale, which embodies the dream of truly human values, must be imbued with the experience of history in order to really help a person survive and not break in the full of tragic trials and cataclysms of our time.”

The central conflict of the play "The Naked King", as well as a number of his other plays, is a person under the rule of tyranny, a person opposing dictatorship, defending his spiritual freedom and the right to happiness. Being aware of the monstrous moral illogicalism of the totalitarian regime, when the individual is subjected to dehumanization, Schwartz proclaims in the play the concept of “basic life”, characteristic of a fairy tale, in which the main thing is a strong sense of moral norm. It is in “The Naked King” that the concept of “main” and “false” life, their complex relationship, is revealed with particular force. To convey these thoughts to the reader (viewer), Schwartz uses motifs from famous Andersen fairy tales in his plays. The traditional, well-known fairy-tale situation in E. Schwartz's plays somewhat reduces the reader's interest in the basis of the plot; allegory becomes the main source of entertainment.

Contaminating the motifs of fairy tales by G.-H. Andersen ("The Princess and the Swineherd", "The Princess and the Pea", "The King's New Clothes"), E Schwartz places his heroes in fundamentally new conditions, in tune with his era. The beginning of the play is quite recognizable, the main characters are a princess and a swineherd, but the functional characteristics of both differ significantly from their fairy-tale prototypes. Schwartz ignores the problem of social inequality in the relationships between the main characters. At the same time, the image of Princess Henrietta undergoes a greater transformation. Unlike Andersen's heroine, Schwartz's princess is devoid of prejudices. However, for Schwartz the relationship between the characters is not particularly important; the meeting of two young people in the play serves as the beginning of the main action. The union of lovers is opposed by the will of the king-father, who is going to marry his daughter to a neighboring ruler. Henry decides to fight for his happiness and this desire sets up the main conflict of the play.

The second scene of the first act introduces us to the rules of government of the neighboring state. With the arrival of the princess, the main question of interest to the king becomes the question of her origin. The nobility of the princess's origin is tested with the help of a pea placed under twenty-four feather beds. Thus, the motif of Andersen's fairy tale "The Princess and the Pea" is introduced into the play. But here, too, Schwartz rethinks the proto-plot, including in the plot development the motive of a contemptuous attitude towards social inequality. The main character is able to neglect her high origin if it interferes with her love for Henry.

The question of “purity of blood” in the play becomes a kind of response of the writer to modern events at the time the play was written. Evidence of this is the many replicas of the characters in the play: “... our nation is the highest in the world..." ; "Valet: Are you Aryans? Heinrich: A long time ago. Valet: That's good to hear" ; "King: What a horror! Jewish Princess" ; "...they started burning books in the squares. In the first three days, they burned all the really dangerous books. Then they started burning the rest of the books indiscriminately". The orders of the “highest state in the world” are reminiscent of the fascist regime. But at the same time, the play cannot be considered a straightforward anti-fascist response to the events in Germany. The king is a despot and tyrant, but one cannot see the features of Hitler in him. The king of Schwartz once " He attacked his neighbors all the time and fought... now he has no worries. His neighbors took all the land that could be taken from him". The content of the play is much broader, "Schwartz's mind and imagination were absorbed not in private issues of life, but in fundamental and most important problems, problems of the destinies of peoples and humanity, the nature of society and human nature." The fairy-tale world of this state becomes a very real world of despotism. Schwartz creates in the play there is an artistically convincing universal model of tyranny. The writer comprehended the tragic conditions of social life of his country in the 30s and 40s, treating the problem of fascism only as another “evidence of the repetition of many bitter patterns of life." An acute awareness of the contradictions and conflicts of his contemporary era forced the playwright to put forward as the main theme of preserving personality in a person, concentrating attention on the ontological dominants of well-known material. That is why the world of a “militarized state” is alien to Henrietta, which she refuses to accept: " Everything here is to the drum. The trees in the garden are lined up in platoon columns. Birds fly by battalion... And all this cannot be destroyed - otherwise the state will perish..."The militarized order in the kingdom has been brought to the point of absurdity; even nature must submit to the military regulations. In the "highest state in the world" people, on command, tremble with reverence before him and turn to each other." uplink", flattery and hypocrisy flourish (compare, for example, the dystopian world created by Shchedrin's Ugryum-Burcheev).

The socially “low” Henry’s struggle for his love leads him to rivalry with the king-groom. Thus, the plot of the play includes the motif of another Andersen fairy tale, “The King’s New Clothes.” As in the borrowed plot, the heroes dress up as weavers and in a certain situation “reveal” the true essence of their ruler and his retinue. A kingdom in which it is beneficial for the king to know only the pleasant truth rests on the ability of his subjects to reject the obvious and recognize the non-existent. They are so used to lying and being hypocrites that they are afraid to tell the truth." tongue won't turn". At the intersection of the fairy-tale image of the “highest state in the world” and the realistically conventional model of tyranny and despotism, a special world of the state arises, in which the false, non-existent becomes completely real. Therefore, everyone who looks at the fabrics, and then the “sewn” outfit of the king, is not deceived, but acts in accordance with the “charter” of the kingdom - creates a kind of mystified reality.

In his fairy tale, Andersen examines the problem of the permissibility of a person in power whose personality is limited to one characteristic - a passion for clothes (a similar characteristic is used, for example, by G. Gorin in the play "That Same Munchausen"). The storyteller considers the stupidity and hypocrisy of his subjects primarily from a moral and ethical point of view. Schwartz brings to the fore socio-philosophical issues and in a unique form explores the nature and causes of tyranny. Exposing evil, despotism, stupidity, tyranny, philistinism is the main problem of the work, which forms a system of collisions and their active interaction with each other. One of the characters states: " Our entire national system, all traditions rest on unshakable fools. What will happen if they tremble at the sight of a naked sovereign? The foundations will shake, the walls will crack, smoke will rise over the state! No, you can't let the king out naked. Pomp is the great support of the throne". The plot development gradually clarifies the reasons for the confident reign of the tyrant. They lie in the slavish psychology of the average person, unable and unwilling to critically comprehend reality. The prosperity of evil is ensured due to the passive, philistine attitude of the crowd to the realities of life. In the scene in the square, a crowd of onlookers has gathered once again admire the new dress of their idol. The townspeople are delighted with the outfit, even before the king appears in the square. Having seen their ruler really naked, people refuse to objectively perceive what is happening, their life is based on the habit of total tyranny and a blind conviction in the need for the power of a despot .

Hints of the topical contradictions of modernity can be seen in E. Schwartz at all levels: in figurative characteristics, remarks of characters, and most importantly, in the writer’s desire to portray modernity at the level of associative-symbolic subtext. In the final scene of the play, Henry states that " the power of love has broken all obstacles", but, given the complex symbolism of the play, such a finale is only an external ontological shell. The absolutization of tyranny, the passive philistine attitude of people to life, the desire to replace reality with a mystified reality remain intact. However, it remains obvious that Schwartz was able to rethink Andersen’s plot, which acquired a completely new meaning in the play.

Literature

1. Borev Yu.B. Aesthetics. 2nd ed. – M., 1975. – 314 p.

2. Bushmin A. Continuity in the development of literature: Monograph. – (2nd ed., additional). – L.: Artist. lit., 1978. – 224 p.

3. Golovchiner V.E. On the question of the romanticism of E. Schwartz // Scientific. tr. Tyumen University, 1976. – Sat. 30. – pp. 268-274.

4. Lipovetsky M.N. Poetics of a literary fairy tale (Based on the material of Russian literature of the 1920-1980s). – Sverdlovsk: Ural Publishing House. Univ., 1992. – 183 p.

5. Neamtsu A.E. Poetics of traditional plots. – Chernivtsi: Ruta, 1999. – 176 p.

6. Schwartz E. Ordinary Miracle: Plays / Comp. and entry article by E. Skorospelova - Chisinau: Lit Artistic, 1988. - 606 p.

7. Schwartz E. Fantasy and reality // Questions of literature. – 1967. – No. 9. – P.158-181.

The article was received by the editorial office on November 16, 2006.

Keywords: Evgeny Schwartz, Evgeny Lvovich Schwartz, criticism, creativity, works, read criticism, online, review, review, poetry, Critical articles, prose, Russian literature, 20th century, analysis, E Schwartz, drama, naked king

In all the works of the outstanding playwright E. A. Schwartz, the main features of his work were manifested: the internal independence of the plots he developed, the novelty of characters, human relationships, the complex interaction of imagination, reality and fairy tales. In plays, the fantastic naturally enters into ordinary life and mixes with it almost imperceptibly. Borrowing the form of allegory from a fairy tale, the playwright fills it with new content. One of Schwartz’s favorite techniques is that many of the comic situations of his plays are built on obtaining an effect opposite to the expected one, and this clearly shows the grotesque nature of Schwartz’s contradiction. One of these plays in which the grotesque shapes the writer’s fairy-tale style is “The Naked King.”

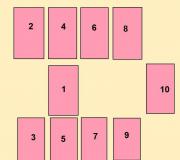

The play “The Naked King” was written by E. L. Schwartz in 1934. The author included plot motifs from three fairy tales by H. H. Andersen in the composition of the play: “The Swineherd”, “The Princess and the Pea”, “The King’s New Clothes”. Having creatively reworked the plots of famous fairy tales, Schwartz created a new work - the play "The Naked King". The main characters of the fairy tale by E. L. Schwartz, two inseparable swineherd friends, Henry, Christian, and the Princess, with an independent and cheerful character, go through many trials. This play does not have three separate stories with different princesses, but one big story where the same princess lives and acts. Her image is one of the main ones, it connects all the characters with each other, all the action and all the conflicts of the play develop around the princess.

In the fairy tale by E. L. Schwartz, the swineherd is actually a commoner, and the story of his acquaintance with the princess is the beginning of the play. The beginning reveals the main features of a fairy tale. “A fairy tale is replete with miracles. There are terrible monsters, wonderful objects, wonderful events, a journey to another distant kingdom.” As in fairy tales, Henry and Christian have a “magic assistant” - a bowler hat with a talking nose and jingling bells that play any dance tune. It is with magical objects that the grotesque reflection of life is associated in the fairy tale play. “In the grotesque, the primary convention of any artistic image is doubled. Before us is a world that is not only secondary in relation to the real, but also built on the principle of “by contradiction.” The categories of causality, norms, patterns, etc., which are familiar to us, dissolve in the grotesque world.

That is why fantasy is so characteristic of the grotesque; it especially clearly destroys the connections we are accustomed to.”

Schwartz's reminiscence of Gogol's nose serves as a way of exposing the hypocrisy of the society in which the Princess lives. The Nose from the Cauldron tells how the ladies of the court “save money” by dining for months on end in other people’s houses or the royal palace, while hiding the food in their sleeves. Schwartz's fantastic elements are full of deep meaning and, like Gogol's, are a means of satirical denunciation. Gogol's nose casts doubt on the trustworthiness of his master, Schwartz's nose makes him doubt the integrity of the court circle, he openly exposes the hypocrisy of high society, its false canons.

One of the author’s satirical devices is the dialogue between the nose and the ladies, another is the refrain of the repeated phrase of one of the court ladies, which she addresses to the princess: “I beg you, be silent! You are so innocent that you can say absolutely terrible things.” At the end of the play, Henry’s friend Christian says the same phrase to the princess, which produces a strong comic effect. Christian, just like the magic cauldron, performs the functions of an “assistant” in the play. The author gives the magic cauldron another function: to express Henry’s innermost dreams and desires. The bowler hat sings the song of Henry in love, in which he expresses confidence that Henry, having overcome all obstacles, will marry the princess. Schwartz's kind humor can be felt in the princess's dialogues with her court ladies about the number of kisses she should exchange with her beloved Henry. The comedy of the situation is emphasized by the unfeigned horror of the court ladies forced to obey the princess. The comic effect is enhanced when the angry king threatens the ladies with first burning them, then cutting off their heads and then hanging them all on the highway. Having mercy, he promises to leave all the ladies alive, but “to scold them, scold them, nag, nag them all their lives.”

Schwartz continues and deepens Andersen's tradition of satirically ridiculing the philistinism of aristocratic society. The dialogue of the court ladies with Henry and Christian, who gave nicknames to the pigs as titled persons - Countess, Baroness, etc., is based on the play on words, on their ambiguity. The princess’s response to the indignation of her ladies: “Call pigs with high titles!” - sounds like a challenge: “The pigs are his subjects, and he has the right to bestow upon them any titles.” The princess, according to the author, personifies the charm of youth, beauty and the poetry of high feelings, so it is not surprising that Henry immediately falls in love with her and, before parting, promises to marry her. Unlike Andersen's heroines, the princess in Schwartz's play is a cheerful, sincere girl with an open character, to whom all falsehood and hypocrisy are alien. She doesn’t even know how to swear, so at the end of the play she scolds the stupid king according to the piece of paper that Henry wrote to her. According to the laws of a fairy tale, the lovers are separated: the angry king-father orders the swineherds to be expelled from the country, and wants to marry the princess to the king of a neighboring state. In Schwartz's tale, Henry's promise to marry the princess serves as a continuation of the play's action. Further, the action of the play develops based on the fairy tale “The King’s New Clothes,” but in Andersen’s fairy tale there is no princess, and for Schwartz, the plot begins with the arrival of the princess in the kingdom of the stupid king. In this part, central to the playwright’s plan, the accusatory and satirical pathos reaches the power of the grotesque. The play, written after Hitler came to power in Germany, has a clear political subtext. The methods of satirical denunciation of the stupid king are straightforward. The task that he gave to the Minister of Tender Feelings was to find out the origin and behavior of the princess, the gendarmes, the selective fellows, who are distinguished by such discipline that on command they plug their ears and make the population faint, which is trained by the gendarmes to “enthusiastic meetings” - these are details indicating a despotic character the power of the king.

If at the beginning of the play the references to the king-groom are of a harmless humorous nature, then in the second act of the play the author gives certain characteristics. Thus, in the figure of the stupid king it is not difficult to recognize the sinister features of another famous personality - the German Fuhrer, who was later given the definition of “possessed.” Phrases like “I’ll burn”, “sterilize”, “kill like a dog”, “don’t you know that our nation is the highest in the world” are very typical. The cook's story to Heinrich about the "new order", about the "fashion for burning books in squares", as a result of which not a single book remained in the country, shows the horror of the common man intimidated by terror and despotic power. As in all his plays, Schwartz creates in “The Naked King” the flavor of his era, emphasizes the realistic features of the political situation of the time, when the ominous threat of fascism hung over the whole world, reflects the characteristic features of fascism: the motive of the chosenness of the Aryan people, militarism, racism. An alarming note is heard in the play when describing the king's tyranny in the scene when he wakes up. The trumpeters blow, everyone praises him, and from the height of his bed he throws a dagger at his valet. In this scene, the author shows how human dignity is suppressed, how people surrounding the stupid king encourage and cultivate the worst traits in him, elevating them to the level of national virtue.

The images of the First Minister, the Minister of Tender Feelings, the jester, the valet, the cook, the poet, the scientist, the ladies-in-waiting, marching in formation and reporting like soldiers, emphasize the danger of the existence of people with paralyzed will, who help legitimize the policy of terror, destruction, bullying and threats. It was thanks to such people that Hitler came to power. Schwartz warned about this danger in his play. There are many techniques of satirical ridicule in the play. The stupid king calls the First Minister nothing more than “a truthful old man, an honest, straightforward old man,” constantly emphasizing that the First Minister “speaks the truth straight to the face, even if it is unpleasant.” Both the king, and his minister, and all his subjects are openly hypocritical, knowing that no one will dare to tell the king the truth, since they may pay for it with their lives. Everyone around the king lives in fear of the truth. In the end, the king pays severely for his injustice. He is deceived by the Princess, who hides the fact that she felt the pea through twenty-four feather beds so that she would not be married to him. He is cruelly deceived by court flatterers who deliberately admire the non-existent fabrics and costume he is wearing. As a result, he solemnly rides out into a crowded square completely naked.

Evgeny Schwartz is a famous Soviet writer, poet, playwright and screenwriter. His plays have been filmed more than once, and also staged on the stages of leading theaters, and many fairy tales are still popular not only among young, but also among adult readers. A feature of his works is a deep philosophical subtext with apparent simplicity and even recognition of the plots. Many of his works became original interpretations of stories already familiar to readers, which he reworked so interestingly that new works made it possible to reconsider well-known fairy tales.

Youth

Evgeny Schwartz was born in 1896 in Kazan into the family of a doctor. His childhood was spent in numerous moves, which was associated with his father’s work. In 1914, the future famous writer entered the law faculty of Moscow University. Already at this time he became very interested in theater, which predetermined his future fate. During the First World War he served in the army and was promoted to ensign.

After the February Revolution, Evgeny Schwartz entered the Volunteer Army and took part in the hostilities of the white movement. After demobilization, he began working in a theater workshop.

Carier start

In 1921, the future playwright moved to Petrograd, where he began acting on stage. Then he established himself as an excellent improviser and storyteller. His literary debut took place in 1924, when the children's work “The Story of the Old Balalaika” was published. A year later, Evgeny Schwartz was already a permanent employee and author of two well-known children's magazines. The 1920s were very fruitful in his career: he composed several works for children, which were published in separate editions. The year 1929 was significant in his biography: the Leningrad theater staged the author’s play “Underwood” on its stage.

Features of creativity

The writer worked hard and fruitfully. He not only composed literary works, but also wrote librettos for ballets, came up with funny captions for drawings, made satirical reviews, and reprises for the circus. Another characteristic feature of his work was that he often took familiar classical stories as the basis for his works. Thus, Schwartz wrote the script for the cult movie Cinderella, which was released in 1946. The old fairy tale began to sparkle with new colors under the pen of the author.

For example, Evgeny Schwartz carefully described those characters who remained impersonal in the original work. The prince became a mischievous and funny young man, the king amused the audience with his witty remarks and sweet simplicity, the stepmother turned out to be not so much evil as a boastful and ambitious woman. The figure of the heroine's father also acquired the real features of a caring and loving parent, while usually his image remained unclear. So, the writer could breathe new life into old works.

Military theme

The works of Evgeniy Lvovich Schwartz amaze with the variety of themes. During the war, he remained in besieged Leningrad and refused to leave the city. However, after some time he was nevertheless taken out, and in Kirov he wrote several essays about the war, among them the play “One Night,” which was dedicated to the defenders of the city. The work “The Distant Land” tells the story of evacuated children. Thus, the author, like many of his contemporaries, composed a number of his works about the terrible days of wartime.

Film work

Fairy tales by Evgeniy Schwartz have been filmed several times. It has already been said above that it was he who became the author of the script for the famous “Cinderella”. In addition to this work, the general public probably still remembers the old film “Marya the Mistress,” also based on his work.

The writer again, in his characteristic subtle and philosophical manner, retells in a new way the story familiar to everyone from childhood about an evil merman who kidnapped a beautiful young woman. The author's undoubted success is the introduction of a child into the story as one of the main characters. After all, previous fairy tales with a similar plot usually made do with two positive characters (the kidnapped princess and her liberator) and one negative one. The author expanded the scope of the plot, which benefited the film.

"An Ordinary Miracle"

Evgeniy Schwartz's books are distinguished by complex intellectual overtones, which soon became the author's main technique. Some of his works sometimes, even with all their apparent simplicity of plot, turned out to be difficult to understand. The author worked on his probably most famous play, “An Ordinary Miracle,” for ten years. It was released in 1954 and was soon staged. Unlike his other tales, this work has no specific historical attachment; the text contains only a mention that the owner’s estate is located in the Carpathian Mountains. The characters in the play turned out to be very ambiguous: the king, despite all his cruelty, unreservedly loves his daughter, the hunter, who is initially shown as a comedic hero, agrees to kill the hundredth bear. The characters constantly reflect and carefully analyze their actions from a psychological point of view, which was not at all typical for traditional fairy tales.

Productions and film adaptations

Evgeny Schwartz created almost all of his works for children. In this series, the play “An Ordinary Miracle” stands out, which is more likely intended for an adult reader. Criticism, as a rule, avoided the productions. Some authors of the articles noted the originality of the play, but reproached the author for the fact that his heroes do not fight for their happiness, but rely entirely on the will of the wizard, which is not entirely fair, since the Princess and the Bear, on the contrary, behave in the most unexpected ways during the course of the story. for the Master himself.

The first productions, however, were warmly received by the public, as well as by some other writers, who appreciated the subtle philosophical humor and originality of the characters. Also, at different times, film adaptations of this play were made: black and white by E. Garin and color by M. Zakharova. The latter acquired cult status due to its star cast, excellent director's production, wonderful music, original interpretation of the characters, as well as colorful scenery.

"Shadow"

The biography of Evgeny Schwartz is inseparably connected with his work for the theater, for which he wrote several famous plays. The one mentioned in the subtitle was created in 1940. It was composed specifically for the stage production. Along with some other works of the playwright, it is distinguished by some bombast. This is a very specific story that tells about an unusual incident that happened to a scientist who lost his shadow. After some time, the latter took his place and caused him a lot of harm.

However, the devotion of the girl who loved him helped him overcome all the trials. This work was filmed by N. Kasheverova, and the two main roles were played by the famous Soviet artist O. Dal.

Other works

In 1944, Schwartz wrote the philosophical fairy tale "Dragon". In this work, he again resorted to his favorite technique: he remade already familiar folk stories, but this time the folklore motifs of the Asian peoples about a terrible dragon, which no one can kill, since in due time the winner also turns into dictator. In this play, the author conveyed the idea that people would rather be content with a tolerable life under a dictator than risk it in the struggle for freedom. None of them are able to feel truly free, and therefore the main character, the knight Lancelot, having defeated the monster, turns out to be a loser because he was unable to change the psychology of people. The work was filmed by M. Zakharov in 1988.

The fairy tales that Evgeniy Schwartz wrote in his time are still popular. “Lost Time” (more precisely, “The Tale of Lost Time”) is a work intended for children. In this story, the author conveys the idea of the need to cherish every minute of time and not waste it in vain. Despite the familiarity of the plot, the composition, nevertheless, is distinguished by its originality, since this time the writer transferred the action of the work to the modern era. The story tells about unlucky children who lost many precious watches, stolen by evil wizards, who at this expense turned into teenagers, and the main characters became old men. They had to go through many tests before they managed to regain their usual appearance. The fairy tale was filmed by A. Ptushko in 1964.

Writer's personal life

The author's first wife was a theater actress in Rostov-on-Don. However, after some time, he divorced her and married a second time to Ekaterina Zilber, with whom he lived until his death. However, they never had children. Everyone called Evgeniy Schwartz an extremely romantic person, prone to eccentric actions. For example, he obtained consent for the marriage of his first wife by jumping into cold water in winter. This first marriage turned out to be happy: the couple had a daughter, Natalya, who was the meaning of life for the writer.

However, the playwright’s second love turned out to be much stronger, so he decided to make this break. The author died in 1958 in Leningrad. The cause of death was a heart attack, as he had previously suffered from heart failure for a long time. In our time, the writer’s work is still relevant. Film adaptations can often be seen on television, not to mention theatrical productions based on his works. The school curriculum includes reading some of his fairy tales and plays.

Sections: Literature

Untitled Document

The plays of Evgeny Schwartz and films based on his scripts are now known all over the world. The greatest interest in Schwartz's legacy is caused by works associated with fairy tale motifs. The playwright, turning to famous characters and common fairy tale plots, and sometimes combining several in one work, fills them with special content. Behind the words and actions of the characters one can discern the author’s perception of reality, the moral assessment of human actions, and the outcome of the struggle between good and evil.

When familiarizing yourself with the dramaturgy of E. Schwartz in literature lessons, it is necessary to analyze fairy tale plots as reworked by the author, the speech and actions of the characters in the context of the conditions in which they live and act, and to consider the author’s techniques and turns of speech. Literary and linguistic analysis of the text leads to the need to turn to the historical conditions of Russia in the 20th century and to the biography of the writer himself. Otherwise, it is impossible to understand the full significance of Schwartz’s dramaturgy and to trace the main distinguishing feature of his works - morality, which reflects the basic concepts of good and injustice, honor and cowardice, love and sycophancy, and the right of an individual to manipulate the consciousness of people.

Schwartz's dramaturgy is still in demand and is an indispensable part of the repertoires of famous theaters, and films based on the script of his plays (An Ordinary Miracle, Cinderella, Kill a Dragon) are loved by millions of admirers of the playwright's talent.

In literature classes, almost no attention is paid to the work of Evgeniy Lvovich Schwartz, and the study of famous fairy tales in comparison with how their themes and characters are embodied in the writer’s works provides an opportunity to get to know him better.

Formation of E.L. Schwartz as a playwright

In the host of great writers, there are few storytellers. Their gift is rare. Playwright Evgeny Schwartz was one of them. His work dates back to a tragic era. Schwartz belonged to a generation whose youth was during the First World War and revolution, and whose maturity was during the Great Patriotic War and Stalinist times. The playwright's legacy is part of the artistic self-knowledge of the century, which is especially obvious now, after it has passed.

Schwartz's path to literature was very complex: it began with poems for children and brilliant improvisations, performances based on scripts and plays written by Schwartz (together with Zoshchenko and Lunts). His first play, “Underwood,” was immediately dubbed “the first Soviet fairy tale.” However, the fairy tale did not have an honorable place in the literature of that era and was the object of attacks by influential teachers in the 20s, who argued for the need for a harshly realistic education of children.

With the help of a fairy tale, Schwartz turned to the moral fundamental principles of existence, the simple and indisputable laws of humanity. “Little Red Riding Hood” was staged in 1937, and “The Snow Queen” in 1939. After the war, at the request of the Moscow Youth Theater, the fairy tale “Two Maples” was written. Generations grew up on puppet theater plays; The film Cinderella, based on Schwartz's script, was a success that stunned him. But the main thing in his work - philosophical fairy tales for adults - remained almost unknown to his contemporaries, and this is the great bitterness and tragedy of his life. Schwartz's wonderful triptych - "The Naked King" (1934), "Shadow" (1940), "Dragon" (1943) - remained as if in literary oblivion. But it was in these plays that there lived a truth that was absent in the literature of those years.

“Evgeniy Schwartz’s plays, no matter what theater they are staged in, have the same fate as flowers, sea surf and other gifts of nature: everyone loves them, regardless of age. ...The secret of the success of fairy tales is that, telling about wizards, princesses, talking cats, a young man turned into a bear, he expresses our thoughts about justice, our idea of happiness, our views on good and evil,” noted creativity researcher E. Schwartz N. Akimov.

Why is Schwartz interesting to the modern reader and viewer? In the plots of his plays, based on traditional images, one can read a clearly tangible subtext, which makes us understand that we have touched some wisdom, kindness, high and simple purpose of life, that just a little more, and we ourselves will become wiser and better. To understand the origins of Schwartz’s dramatic creativity and the peculiarities of his artistic vision of the world, it is necessary to turn to his biography. Taking into account the fact that material about the playwright’s life remains outside the school curriculum for most students, studying the facts of Schwartz’s biography will make it possible to get to know him as a person and a writer, and with the historical conditions reflected in his works.

Transformation of traditional fairy tale images in the plays of E. Schwartz

(using the example of the play “Shadow”)

In many of Schwartz’s plays, motifs from “alien” fairy tales are visible. For example, in The Naked King, Schwartz used plot motifs from The Swineherd, The King's New Clothes and The Princess and the Pea. But it is impossible to call The Naked King, like other plays by Evgeniy Schwartz, dramatizations. Of course, both “The Snow Queen” and “The Shadow” use motifs from Andersen’s fairy tales: “Cinderella” is an adaptation of a folk tale, and “Don Quixote” is a famous novel. Even in the plays “Dragon”, “Two Maples” and “An Ordinary Miracle”, certain motifs are clearly borrowed from famous fairy tales. Schwartz took well-known plots, as Shakespeare and Goethe, Krylov and Alexei Tolstoy did in their time. For Schwartz, old, well-known images began to live a new life and were illuminated by a new light. He created his own world - a world of sad, ironic fairy tales for children and adults, and it is difficult to find more original works than his fairy tales. It is advisable to begin getting to know Schwartz with an analytical reading of his plays: what plots of famous fairy tales will schoolchildren notice?

Turning to Andersen’s work was by no means accidental for Schwartz. Having come into contact with Andersen's style, Schwartz also comprehended his own artistic style. The writer in no way imitated a high example, and certainly did not stylize his heroes after Andersen’s heroes. Schwartz's humor turned out to be akin to Andersen's humor.

Telling in his autobiography the story of one of the fairy tales he wrote, Andersen wrote: “... Someone else’s plot seemed to enter my blood and flesh, I recreated it and then only released it into the world.” These words, set as the epigraph to the play “Shadow,” explain the nature of many of Schwartz’s plans. The writer’s accusatory anger in “The Shadow” was directed against what A. Kuprin once called “the quiet deterioration of the human soul.” The duel of the creative principle in a person with a sterile dogma, the struggle of indifferent consumerism and passionate asceticism, the theme of the defenselessness of human honesty and purity in the face of meanness and rudeness - this is what occupied the writer.

Betrayal, cynicism, callousness - the sources of any evil - are concentrated in the image of the Shadow. The Shadow could steal from the Scientist his name, appearance, his bride, his works, she could hate him with the intense hatred of an imitator - but for all that, she could not do without the Scientist, and therefore in Schwartz the ending in the play is fundamentally different than in Andersen’s fairy tale . If in Andersen the Shadow defeated the Scientist, then in Schwartz it could not emerge victorious. “The shadow can only win for a while,” he argued.

Andersen's “Shadow” is usually called a “philosophical fairy tale.” Andersen's scientist is full of vain trust and sympathy for a person in whose guise his own shadow appears. The scientist and his shadow went traveling together, and one day the scientist said to the shadow: “We are traveling together, and besides, we have known each other since childhood, so shouldn’t we have a drink on a first name basis?” This way we will feel much more free with each other.” “You said this very frankly, wishing us both well,” responded the shadow, which, in essence, was now the master. - And I will answer you just as frankly, wishing you only the best. You, as a scientist, should know: some people cannot stand the touch of rough paper, others shudder when they hear a nail being driven across glass. I experience the same unpleasant feeling when you say “you” to me. It’s as if I’m being pressed to the ground, just like when I occupied my previous position with you.” It turns out that a joint “journey” through life does not in itself make people friends; An arrogant hostility towards each other, a vain and evil need to dominate, to enjoy privileges, to flaunt their fraudulently acquired superiority still nest in human souls. In Andersen's fairy tale, this psychological evil is embodied in the personality of the pompous and mediocre Shadow; it is in no way connected with the social environment and social relations thanks to which the Shadow manages to triumph over the Scientist. And, starting from Andersen’s fairy tale, developing and concretizing its complex psychological conflict, Schwartz changed its ideological and philosophical meaning.

In Schwartz's tale, the scientist turns out to be stronger than his ethereal and insignificant shadow, while in Andersen he dies. Here you can see a deeper difference. In “The Shadow,” as in all of Schwartz’s other fairy tales, there is a fierce struggle between the living and the dead in people. Schwartz develops the conflict of the tale against a broad background of diverse and specific human characters. Around the dramatic struggle of the scientist with the shadow in Schwartz’s play, figures appear, which in their totality make it possible to feel the entire social atmosphere.

This is how a character appeared in Schwartz’s “Shadow” that Andersen did not have and could not have had - the sweet and touching Annunziata, whose devoted and selfless love is rewarded in the play with the salvation of the scientist and the truth of life revealed to him. This sweet girl is always ready to help others, always on the move. And although in her position (an orphan without a mother) and character (easy-going, friendly) she is somewhat reminiscent of Cinderella, with her whole being Annunziata proves that she is a real kind princess, who must be in every fairy tale. Much of Schwartz's design explains the important conversation that takes place between Annunziata and the scientist. With barely noticeable reproach, Annunziata reminded the scientist that he knew about their country what was written in the books. “But you don’t know what’s not written about us there.” “You don’t know that you live in a very special country,” Annunziata continues. “Everything that is told in fairy tales, everything that seems fiction among other nations, actually happens to us every day.” But the scientist sadly dissuades the girl: “Your country - alas! - similar to all countries in the world. Wealth and poverty, nobility and slavery, death and misfortune, reason and stupidity, holiness, crime, conscience, shamelessness - all this is mixed so closely that you are simply horrified. It will be very difficult to unravel all this, take it apart and put it in order so as not to damage anything living. In fairy tales it’s all much simpler.” The real meaning of these words of the scientist lies, among other things, in the fact that in fairy tales everything should not be so simple, if only the fairy tales are true and if the storytellers courageously face reality. “To win, you have to go to death,” explains the scientist at the end of the tale. “And so I won.”

Schwartz also showed in “The Shadow” a large group of people who, with their weakness, or servility, or meanness, encouraged the shadow, allowed it to become insolent and unbelted, and opened the path to prosperity for it. At the same time, the playwright broke many of our ingrained ideas about fairy tale heroes and revealed them to us from the most unexpected side. Gone, for example, are the days of cannibals who angrily rolled their pupils and bared their teeth threateningly. Adapting to new circumstances, the cannibal Pietro joined the city pawn shop, and all that remains of his ferocious past are outbursts of rage, during which he fires a pistol and is immediately indignant that his own daughter does not give him enough filial attention.

As the action of Schwartz's tale unfolds, its second plan emerges with increasing clarity, a deep and intelligent satirical subtext, the peculiarity of which is that it does not evoke superficial associations with the hero to whom they are addressed, but is associated with him internally. , psychological community.

Let's look at this with an example. “Why don’t you go? - Pietro Annunziata shouts. - Go reload the pistol immediately. I heard that my father was shooting. Everything needs to be explained, everything needs to be poked into. I’ll kill you!” It is difficult to imagine a more unusual alternation of intonations of widespread parental reproach - “you need to rub your nose into everything” - and rude robber threats - “I’ll kill you!” And, nevertheless, this alternation turns out to be quite natural in this case. Pietro speaks to Annunziata in exactly the same words that irritated fathers speak to their grown-up children. And precisely because these words turn out to be quite suitable for expressing those absurd demands that Pietro makes of his daughter, they betray their meaninglessness and automaticity: they do not oblige anyone to anything and do not entail any consequences. As a satirist, Schwartz, of course, exaggerates, aggravates the funny in his characters, but never deviates from their attitude towards themselves and others.

One scene in The Shadow depicts a crowd gathered at night in front of the royal palace; Having succeeded in meanness and trickery, the Shadow becomes king, and in the short remarks of people, in their indifferent chatter, you can hear the answer to the question of who exactly helped the Shadow achieve his goal. These are people who care about nothing except their own well-being - outright people-pleasers, lackeys, liars and pretenders. They make the most noise in the crowd, which is why it seems that they are the majority. But this is a deceptive impression; in fact, the majority of those gathered hate the Shadow. No wonder the cannibal Pietro, who now works for the police, appeared on the square, contrary to orders, not in a civilian suit and shoes, but in boots with spurs. “I can confess to you,” he explains to the corporal, “I deliberately went out in boots with spurs. Let them know me better, otherwise you’ll hear so much that you won’t sleep for three nights.”

Andersen's short tale is a 19th-century European novel in miniature. Its theme is the career of an arrogant, unprincipled shadow, the story of its path to the top: through blackmail, deception, to the royal throne. The Shadow's attempt to persuade the Scientist to become his shadow is only one of its many ways to the top. The Scientist’s disagreement leads to nothing; it is no coincidence that he was not even allowed anywhere after refusing to serve as a shadow; no one found out about his death. In Schwartz's play, all stages of the scientist's negotiations with the shadow are especially emphasized; they are of fundamental importance, revealing the independence and strength of the scientist.

In Andersen's fairy tale, the shadow is practically invulnerable, it has achieved a lot, it itself has become rich, and everyone is afraid of it. In Schwartz's play, it is the moment of the shadow's dependence on the scientist that is emphasized. It is shown not only in direct dialogues and scenes, but is revealed in the very nature of the shadow’s behavior. Thus, the shadow is forced to pretend, deceive, and persuade the scientist in order to obtain in writing his refusal to marry the princess, otherwise he will not get her hand. At the end of the play, the playwright shows not just the dependence of the shadow on the scientist, but the impossibility of its independent existence at all: the scientist was executed - the head of the shadow flew off. Schwartz himself understood the relationship between the scientist and the shadow as follows: “A careerist, a man without ideas, an official can defeat a person animated by ideas and big thoughts only temporarily. In the end, living life wins.” This is a different theme than Andersen’s, a different philosophy.

Under “The Shadow,” Schwartz no longer put the subtitle “a fairy tale on Andersen’s themes,” as he did in his time, for example, under “The Snow Queen.” At the same time, the connection of the play with ancient history is not indifferent to the playwright; over time, it seems to him more and more important, he records and clarifies its character in epigraphs that were not in the first magazine publication of 1940.

The heroes of the play know how the fate of a man without a shadow turned out before. Annunziata, who lives in a country where fairy tales are life, says: “The man without a shadow is one of the saddest fairy tales in the world.” The doctor reminds the scientist: “In the folk legends about the man who lost his shadow, in the monograph by Chamisso and your friend Hans Christian Andersen it is said that...” Scientist: “Let’s not remember what it says. Everything will end differently for me.” And this whole story of the relationship between the scientist and the shadow is built as overcoming a “sad fairy tale.” At the same time, Schwartz’s attitude towards the scientist is not reduced to an unquestioning statement, and his noble, sublime hero, who dreams of making the whole world happy, at the beginning of the play is shown as a man still largely naive, knowing life only from books. As the play progresses, he “descends” to real life, to its everyday life, and changes, getting rid of the naive representation of some things, clarifying and concretizing the forms and methods of struggle for people’s happiness. The scientist constantly addresses people, trying to convince them of the need to live differently.

Schwartz's fairy tale remained a fairy tale, without going beyond the boundaries of the magical world, even when - in the script for "Cinderella", which became the basis of the film - sad skepticism seemed to concern this transformative magic, and the king of the fairy-tale kingdom complained that many fairy tales, for example, about the Cat in boots or about Thumb, “already played,” “everything is in the past for them.” But this only meant that there were new fairy tales ahead, and there was no end in sight. But in the play “Shadow” everything turned out to be different: the fairy-tale country did not seem fairy-tale at all in the good old sense, magic retreated before reality, adapting to it. Little Thumb bargained brutally at the bazaar, and the former cannibals became - one a corrupt journalist, the other - a hotel owner, a burnout and a brawler. Friends betrayed friends, indifference and pretense triumphed, and the happy ending itself, according to a long tradition inevitable for a fairy tale, remained externally preserved, but at the same time was reborn. Theodore, the Scientist, recommended as a friend of Andersen himself, did not win a confident victory over the Shadow, this creature of the reverse world, the embodiment of anti-qualities, but only escaped, fled from the former fairy-tale country. His final line: “Annunziata, let’s go!” sounded no more optimistic than: “Give me a carriage, give me a carriage!” Chatsky.

In order to most fully imagine the transformation of Andersen's characters in Schwartz's play, we turned to a comparative analysis of the characters, the plot, and the embodiment of the author's idea in the works of the same name by these authors. The comparison results can be presented in the form of a table.

Let us summarize the observations made during the comparative characterization of the characters and plot of Andersen’s fairy tale and Schwartz’s play with the same name “Shadow”.

- Schwartz manages to present the traditional plot in a new way, without distorting the original source, to make the scenes not generalized, as is customary in a fairy tale, but related to specific historical and social conditions.

- The playwright introduces aphoristic forms of conveying the essence of psychological phenomena, and this is the skill of an artist who has a keen sense of words.

- Fairy tales in Schwartz's treatment acquire a philosophical character.

- New characters are introduced that make it possible to create a deeper psychological portrait of the time and the hero, to present traditional fairy-tale images in the light of new living conditions that are contemporary to the viewer.

- One can discern a satirical subtext, an exaggeration of the funny in life.

- The traditional traits of the heroes are lost, and their individuality is enhanced.

- The playwright presented the image of the era from the perspective of applying eternal truths to it: good and evil, cruelty and justice, impunity and retribution.

- In Schwartz's plays, there is an understanding of the political life of society during the formation of the ideology of hypocrites and careerists, liars and sycophants, and an understanding of the methods of survival of the satanic principle in society.

- Unable to write openly, Schwartz uses allegory, focusing on the psychology of his contemporary.

Playwright and storyteller. I believed that a fairy tale is one of the oldest genres that helps a sensitive reader and viewer, at least for a while, feel like a child again, understand and accept the world in all its simplicity and complexity.

It was not immediately appreciated by critics. For many years there have been condescending and arrogant intonations, which is a frivolous genre and is only suitable for children's literature. Unpleasant to the Soviet regime, why does the viewer need subtle allusions, transparent associations, wise and crafty advice.

Now he has been returned to the stage, as the viewer expects a confidential, sincere intonation, but at the same time ironic.

"Underwood" is the first play. I thought it was realistic. I don’t understand how I became a storyteller. I heard that he had created a new kind of fairy tale.

Studying at the Moscow University, entering the theater workshop, arriving as part of it in Petrograd, getting acquainted with the literary environment, interest in the “Serapion Brothers”, working as a literary secretary for Chukovsky, collaborating in the children’s magazines “Chizh” and “Hedgehog” and the first plays .

He amazed everyone with his talent for improvisation, an incredible inventor. Meeting with director Akimov (Leningrad Comedy Theater). Akimov said that if there was a position “the soul of the theater,” it would be Schwartz.

1) Naked king. 1934. The playwright's favorite characters appeared for the first time - a power-hungry king, clever ministers, a beautiful princess, swineherds, shepherds and the rest of the population of the fairy-tale city.

The theme is power, which has a deforming influence on the population (Naked King, Shadow, Dragon). Power inspires sacred awe in the people. But a person at the pinnacle of power pays dearly for it, loses friends, loved ones, and is deprived of human warmth. Lies and flattery are always accompanied (in The Naked King there is a grotesque satirical image of the truthful first minister).

The authorities can dress up in any bright clothes, but sincere people, poets, see that the king is naked!

Always a happy ending. In The Naked King, Henry and the princess have a wedding and the king runs away to the palace. But in all these happy endings there is a hint of sadness. You can shame a stupid ruler, but how can you destroy his stupidity? How to convince the crowd that there is no need to make an idol out of a naked king? These questions remain unresolved.

Before us is a new kind of fairy tale. MB is social, satirical or philosophical.

2) Shadow. 1940. Epigraph and “tales of my life” by Andersen. Complex, dialectical relationships between light and darkness, good and evil, friendship and betrayal, love and hatred, i.e. the contradictions that form the basis of life, its development, movement, are interpreted by the playwright wisely and boldly.

The Shadow - Theodore Christian - a vile, disgusting creature, is the creation of the Scientist himself. He himself caused her with careless words. The Shadow, having left the Scientist, goes to power. It is amazing how quickly the dark sides of the human soul are in demand by society. Such a flexible creature is necessary for ministers, privy councilors, etc. An open ending, since the Scientist still believes that the shadow will return, that is, the struggle between good and evil continues.