Nodosaur: oil monster. Well-Preserved Dinosaur Debuts in Canada The Best-Preserved Dinosaur

A fossil of a genus of nodosaurs called "four-legged tanks" has finally become available for public viewing at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, Canada.

The appearance of the found Nodosaurus as presented by scientists |

According to National Geographic, it is the best preserved fossil of its kind.

In one of the local mines, excavator operator Sean Funk accidentally discovered a large lump of dirt (1130 kg) in the ground with an unusual texture and pattern.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

The dinosaur was discovered on March 21, 2011 in Alberta, Canada. Then Sean Funk, an operator at one of the local mines, came across a large lump of dirt with an unusual texture and pattern with the escalator bucket. The weight of the find was 1,100 kg.

For the next six years, the fossil was examined by specialists from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology. What they managed to obtain looks more like a sculpture than a fossil.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

After a long and lengthy work with the dinosaur mummy, it was decided to put it on display as a museum exhibit.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Museum staff say this armored dinosaur is better preserved than any other similar discovery. Ideal condition could have caused the dinosaur to end up at the bottom of the ocean or sea.

“As rare as winning the lottery. The more I look at it, the more it stuns me." - Michael Greshko for National Geographic.

The tip was lined with keratin, a material also found in human nails. | Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

The accumulation of pebble-like masses may be the remains of the nodosaur's last meal. | Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Scientists have not yet been able to get to the skeleton of the fossil, for fear of destroying the well-preserved skin and shell of bone plates.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Computed tomography also did not help, since the stone still remains a poorly transparent substance.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

Nodosaurus lived in the mid-Cretaceous period about 110-112 years ago.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

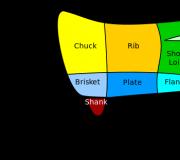

Representatives of this species reached up to 5 meters in length and weighed about 1,300 kg. Their body was covered with dense armor to protect them from other large animals, and two one and a half meter spikes grew on their shoulders.

Photo: nationalgeographic.com/Robert Clark

On the dinosaur's torso, chocolate brown ribs are located next to tan osteoderms and dark gray scales. The tendons that once held the dinosaur's tail (above) ran along its spine and were streaked with dark brown.

Subscribe to Quibl on Viber and Telegram to keep abreast of the most interesting events.

Perhaps everyone has at least once seen some documentary film in which archaeologists carefully cleaned dust and dirt from the remains of a long-dead creature with a small brush. This is how archaeologists work in real life, because archaeological rarities require careful handling. But sometimes researchers discover remains that are amazingly well preserved, despite the passing of millennia. In our review, the archaeological “ten” that surprised and pleased scientists.

1. Mammoth Yuka

Although researchers have discovered several examples of well-preserved mammoths in the past, Yuka is certainly a unique specimen. The remains of this 1.8-meter baby woolly mammoth were accidentally discovered in August 2010 in Yakutia. The animal was between six and nine years old when it died, and the baby mammoth is estimated to be around 39,000 years old.

Researchers say Yuka was most likely killed by humans because clean cuts were found on his carcass and some of the meat was removed. This makes Yuka the first mammoth to show evidence of interaction with humans. The animal also has the best preserved mammoth brain ever discovered by modern scientists.

2. Trilobites

Don't let their appearance fool you; trilobites were actually very effective predators in their time. These marine arthropods lived 521 million years ago, at the beginning of the Cambrian period of the Earth. Trilobite fossils have been found on every continent on Earth, and some of the best-preserved specimens still have soft body parts such as gills and antennae.

They went extinct about 250 million years ago during the Permian mass extinction event. Because trilobites lived for over 300 million years and there were over 20,000 different species, they are considered the most "successful" animal of all time.

The well-preserved remains of a baby Chasmosaurus belli (an adorable cousin of the Triceratops) were discovered in Alberta, Canada in 2015. In 2016, scientists announced that the baby dinosaur was 75 million years old and its skeleton was preserved in stunningly perfect condition, despite its age, in its entirety, and not in parts.

4. Woolly rhinoceros

The 10,000-year-old remains of a woolly rhinoceros have been discovered on a frozen Siberian river in Yakutia. The rhinoceros was nicknamed Sasha after the hunter who found him. Sasha was only a three to four year old "teenager" at the time of his death and is essentially the only complete baby woolly rhinoceros ever found. Although researchers have discovered well-preserved adults of this species, the remains of young rhinoceroses have not yet been encountered.

Sasha was donated to the Yakut Academy of Sciences for study. Although woolly rhinoceroses lived at the same time as woolly mammoths and even shared the same habitat, the two species are not related. The woolly rhinoceros is distantly related to modern rhinoceroses, while the mammoth is related to modern Asian elephants.

5. Cave lion cubs

Animal mummies are often found in Yakutia, because this region is famous for its permafrost. A pair of 10,000-year-old cave lion cubs were also discovered in the region in a Siberian glacier. The two cubs, named Dina and Uyan, were barely a week old when they died. Experts believe their lair was covered by a landslide, and the lack of air is why the bodies were so well preserved.

6. Ancient pregnant mare

In 2000, in archaeological excavations near Darmstadt, Germany, the remains of a distant ancestor of the horse, Eurohippus messelensis, were discovered. Moreover, this ancient horse was in an advanced stage of pregnancy when it died about 48 million years ago, and the fetus inside it was very well preserved. The researchers used micro-analysis using high-resolution X-rays and scanning electron microscopes to learn everything they could about the fetus.

They discovered that the mare's placenta, her internal organs and even the contents of her stomach were still intact. It is the earliest and best preserved fossil specimen of its kind to date. The ancient horse was the size of a modern fox and had four toes on each of its four legs.

7. Bison Mummy

The mummified remains of Bison priscus, an ancient relative of the modern bison, were discovered in the Siberian lowland between the Yana and Indigirka rivers. The frozen climate of Northern Siberia protected the bison from decomposition, so its brain and internal organs were perfectly preserved even after 10,000 years.

Olga Potapova, curator of collections at the Mammoth Site Museum in Hot Springs, South Dakota, helped study the ancient remains. She stated in an interview with Living Science magazine that it is rare to find complete specimens in Siberia and North America. Typically these remains are partially eaten or destroyed.

8. Dog Tumat

Usually, when someone says "place" to a dog, they don't expect the animal to remain in place for 12,000 years. This specimen was found on the banks of the Siberian river Sillyakh by the brothers Yuri and Igor Gorokhov, who were looking for mammoth tusks. The ancient dog is believed to be around 12,400 years old.

Experts examined the body of the dog, named Tumat, for four years. However, an autopsy was carried out only in 2015 and it turned out that the internal organs of the animal were simply perfectly preserved.

9. Dunkleosteus

Dunkleosteus is the most terrible prehistoric fish, the existence of which until recently no one knew. As recently as 380 million years ago, these heavily armored fish were widespread in shallow seas around the world. Typically, they were 9 meters long and weighed up to four tons, i.e. they were the largest vertebrates at that time.

Today their remains are spread throughout the Earth. The skeletal head of Dunkleosteus usually looks like that of a leatherback turtle because it does not have teeth, but plates like a pair of blades.

10. Moa Paw

Moas were flightless birds native to New Zealand. They were completely covered with feathers, except for the beak and paws. Moa were also the largest birds at the time of their existence (they first appeared about 15.8 million years ago). They were New Zealand's dominant herbivores and flourished until the arrival of the Polynesians in the 13th century. Due to overhunting, the moa disappeared about 500 years ago, around 1500.

During an expedition in the Owen Mountains cave system in New Zealand, archaeologists discovered a mummified moa claw, which was practically intact: even the muscles and skin were preserved. Archaeologists sent the claw for analysis and were shocked to discover that it was 3,300 years old.

Anyone who is interested in antiquities will be interested in seeing and.

Find of the Millennium: A perfectly preserved dinosaur was discovered in the Canadian Millennium Quarry.

On the afternoon of March 21, 2011, excavator operator Sean Funk was working quietly, of course, unaware that a dragon would soon appear on his way.

That Monday started out like any other at the Millennium Pit, a huge pit 27 kilometers north of Fort McMurry, Alberta, where energy company Suncor is developing oil. Hour after hour, Funk's powerful excavator dug deeper into the sand, oozing with bitumen, which was formed from the remains of organisms that lived more than 110 million years ago. In his 12 years of work, Sean has found fragments of petrified wood more than once, but never the remains of animals.

Suddenly the excavator bucket caught on something large and hard. Lumps of strange color fell from under the teeth. A few minutes later, the excavator operator and his boss, Mike Gratton, were already examining the red-brown rock: petrified wood or someone's bones? They turned over one of the stones and saw a mysterious pattern: rows of sand-colored circles on a dark gray background.

“Mike immediately decided to check what it was,” Funk said in an interview in 2011, “after all, we had never encountered anything like this before.”

Nearly six years later, I walk through the laboratory doors of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in the windy, dry badlands of Alberta. In the huge room, all you can hear is the hum of ventilation and the blows of dissecting instruments that look like miniature jackhammers, with which laboratory assistants clear fossils.

But my attention is drawn to the blocks in the corner: at first glance, these stones stacked together resemble an impressive, about three meters, sculpture of a dinosaur. Bone plates cover the neck and back, and individual gray scales are clearly visible. The neck is gracefully turned to the left, as if the lizard is trying to reach a succulent plant. But this is not a sculpture at all - a real dinosaur, petrified from the tip of the muzzle to the croup.

REVEALING THE MYSTERY

During life, this huge herbivorous representative of the nodosaur family reached 5.5 meters in length and weighed 1.3 tons. Researchers believe that the lizard was fossilized entirely, but when it was found in 2011, only the front part remained of it - from the head to the croup. Still, this specimen is one of the best dinosaur fossils.

Robert Clark

The longer I look at it, the more impressive it becomes: petrified skin still covering the ridges of the skull; the right front paw lies side by side, fingers spread out. I can count all the scales on the bottom of his foot. “We don’t just have a skeleton,” smiles museum researcher Caleb Brown proudly. “We have a whole dinosaur.”

For paleontologists, discovering a well-preserved lizard is like winning a Nobel Prize. Usually only bones are found, and there are very few cases of minerals replacing soft tissue before it disintegrates. In addition, entire fossils do not always retain the shape of their bodies. For example, the remains of feathered dinosaurs from China are flattened, and North American duck-billed dinosaur “mummies” are just fossilized skeletons with skin imprints on the stone.

Paleobiologist from the University of Bristol Jacob Winter, who is engaged in restoring the color of ancient animals, immediately set about searching for the melanin pigment in the integument of the new lizard. After four days of work, Winter scraped several pieces less than a millimeter thick from its skin. And I was completely amazed by the result. The ancient lizard was simply perfectly preserved. “It’s like he was roaming the earth just a couple of weeks ago,” Winter marvels. “I have never encountered anything like this.”

Yes, this lizard is not just a fossil, but a real mummy, even in the literal sense. After all, the Arabic word “mummy” comes from “mum” - bitumen. In ancient Egypt, noble dead were embalmed with bitumen to protect the body from rotting, and this gave the skin a dark tint. The dinosaur was embalmed in natural conditions, falling into oil sand.

The mummy belongs to a new species (and genus) of armored dinosaurs from the family of nodosaurids. Unlike close relatives - ankylosaurids, nodosaurids did not have a bone club at the end of a powerful tail, but the body was also covered with spiked armor, apparently protecting it from predators. This Cretaceous giant, weighing 1.3 tons and 5.5 meters long, with a pair of half-meter, bull-horn-like spikes on his shoulders, lived 110–112 million years ago and was a huge herbivorous beast that kept to itself, and not in herd.

When this dinosaur was alive, Western Canada was nothing like the cold and windy badlands that greeted me last fall. In the mid-Cretaceous period, warm and humid Pacific breezes walked through the coniferous forests and fern thickets here. Perhaps our dinosaur even came ashore to admire the sea. After all, then, due to rising sea levels, almost the entire territory of present-day Alberta was cut through by a huge sea stretching from the south (from the Gulf of Mexico), on the western shore of which, presumably, the lizard lived.

One day this land animal was washed away by a river that probably overflowed due to heavy rains. The dinosaur's corpse floated downstream for a long time and eventually ended up in the sea, where a few days later the carcass, swollen from gases released by bacteria, burst and sank to the bottom, into soft silt. Later, mineral solutions soaked the porous skin and armor on the back, so that the shape of the dead dinosaur did not change over millions of years.

The lizard, or rather the paleontologists studying it, was very lucky: if it had drowned a hundred meters further, it would have ended up outside the current possessions of Suncor, and it might never have been discovered.

“It was just an amazing discovery,” says Victoria Arbor, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum who studies armored dinosaurs. “This dinosaur is from a completely different era, a different ecosystem, and it’s in excellent condition.” Although Victoria is currently studying another well-preserved dinosaur discovered in Montana in 2014 (most of it has not yet been freed from under a 16-ton slab), she came to look at the Alberta fossil in all stages of removing it from the rock.

RESCUE FROM NOTHING

The integumentary elements of armored dinosaurs are quickly displaced and destroyed during burial. However, this nodosaurid escaped a similar fate. A perfectly preserved fragment of the shell - shown here almost life-size - will help paleontologists understand what these lizards looked like and how they moved.

Robert Clark

Finding words to describe the Canadian dinosaur is not easy, in more ways than one. When this article was being prepared, scientists had already completed the scientific description of the specimen, but “nicknames” had not been invented for it, and the scientific name had not yet appeared in print. And yet, even if unnamed, the fossil has already served science: it has helped to better understand how the shell of nodosaurids works. Typically, when reconstructing a shell, scientists have to rely heavily on guesswork: the bone plates, or osteoderms, that form the exoskeleton are the first to be displaced or completely fall off during post-mortem transformations of the remains. However, this lizard retained not only the osteoderms in place, but also the scales between them.

Moreover, keratin coverings (our nails are also made of this substance) are still present on many osteoderms, which makes it possible to find out how the covering tissues influenced the size and shape of the elements of the shell. “This fossil is our Rosetta Stone: it will help unlock the mysteries of armored dinosaur armor,” says Donald Henderson, curator of dinosaur collections at the Royal Tyrrell Museum.

However, in order to remove this “Rosetta stone” from the “tomb”, efforts commensurate with the mass of the block were required.

As soon as news of the discovery reached Suncor executives, they contacted the museum. Henderson, along with an experienced laboratory technician, Darren Tankey, immediately flew to Fort McMurry on a plane provided by the company. And then they joined the Suncor miners, with whom they worked in 12-hour shifts in the dirt and dust. Finally, they managed to cut out a block weighing 6.8 tons, which contained the dinosaur. But when they began to lift the find under the camera lenses, disaster struck: the block with the dinosaur enclosed in it split into pieces. Oil sands are a very loose material: the fossil simply could not support its own weight.

Tanki spent the whole night thinking about a plan to save the lizard. The next morning, Suncor workers filled the fossil fragments with plaster so paleontologists could transport them to the museum. Instead of board formwork, it was decided to use burlap soaked in a gypsum solution and rolled with rollers.

The plan worked. Having traveled 675 kilometers to the museum, the team handed over the valuable cargo to the preparator Mark Mitchell. The work on extracting the dinosaur lasted five years: Mark spent 7 thousand hours clearing the surface of the mummy from the surrounding rock with surgical precision. “You have to fight for every millimeter,” he explains.

The Mitchell case is nearing its end, but it will take several years, if not decades, to unravel all of the fossil's mysteries. The skeleton, for example, is mostly hidden under the skin and shell. And the fact that the pangolin’s covers were preserved in place is not only a great success, but also a problem: without damaging them, it is impossible to get to the bones. A computed tomography scan funded by the National Geographic Society was not very helpful - nothing could be made out in the images of the mummy’s insides.

However, a lot of interesting things can be collected on the surface of the mummy: this is how Jacob Winter expects to restore the color of the dinosaur based on the composition of the pigments. This may make it possible to understand what kind of terrain the dinosaur chose to move and why it used powerful armor. “Obviously the shell was for protection, but those intricate spikes on the front of the body were too conspicuous,” says Winter. “It is possible that with their help the lizard attracted females or intimidated rivals.” Chemical analyzes showed that the covers contained reddish pigments, and the light spines stood out sharply against the background of the dinosaur's skin.

In May, the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology opened an exhibition of fossils found in Alberta, and the armored dinosaur was the main exhibit. The public saw someone who, over the past five years, had delighted only scientists.

Recently, the remains of a remarkably preserved “mummy” of a dinosaur, whose age is estimated at 110 million years, were exhibited in Alberta, Canada. This herbivorous nodosaur, which weighed 1.3 tons in the wild, was discovered 6 years ago by Canadian miners. “We have not just a skeleton, but a dinosaur, as it should be,” National Geographic quotes explorer Caleb Brown.

Over the course of 7,000 hours of work, scientists cleared the nodosaur's silhouette from fossilized rocks. The dinosaur has preserved its scaly skin and intestines, and its head is clearly visible.

For paleontologists, this is a stunning find - as rare as winning the jackpot in the lottery. Usually only bones and teeth remain in the ground from dinosaurs. And in extremely rare cases, minerals replace soft flesh through the petrification process before it rots.

Hey, the post talked about guts, where's the photo of guts?!

Ankylosaurid?

dinosaur mummy, one of the most unusual phrases in paleontology and history

This dinosaur has been better preserved for 110 million years than I was in my 20s.

Don’t move, and you’ll just turn to stone.

I've always wondered how these fossils are formed? After all, it used to be flesh, and then it became a fossil. What is this fossil? Well... I'll try to look it up on Wikipedia.

These - you mean, with meat, and not just bones? There are two options here:

1). The corpse fell into an environment that causes very rapid petrification (fossaft solutions are especially good in this regard), petrification began in the very first hours, and the body did not have time to rot.

2). The corpse ended up in an environment in which rotting occurs very slowly. Into the desert there. Or, conversely, into a swamp. And there he petrified at the usual pace, without rotting.