Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo - the Italian city of the dead. Scarier than horror: Capuchin catacombs - thousands of mummies in one place

The Capuchin Catacombs are located beneath the Convento dei Cappuccini monastery in Palermo, Italy. Unlike any other catacombs, the entire interior of the Palermo catacombs consists only of mummified, skeletonized and embalmed bodies, because it is the largest necropolis of mummies in the world. This is both a sad and majestic place, because for a long time the catacombs were considered the most elite cemetery, where the most worthy and famous people were buried.

The Capuchin Catacombs (Catacombe dei Cappuccini) is a large underground cemetery of the Capuchin monastery, which is located in the crypt of the Church of Santa Maria della Pace in Palermo on Piazza Cappuccini.

Capuchins (Order of Friars Minor Capuchins) is a monastic order representing one of the branches of the Franciscans. It was founded in 1525 by Brother Matthew Bassi in Urbino. Three years later it received recognition from Pope Clement VII as an independent order.

In June 1534, the first Capuchins arrived in Sicily. They settled near Palermo, west of the city walls on lands where one of the city's districts, Cuba-Calatafimi, is currently located. They were given the small old Norman-era church of Santa Maria della Pace, which was located next to the settlement. In 1565, it was decided to reconstruct the chapel. The renovation work lasted for several decades due to constantly arising difficulties and proposals for various additions. On the initiative of one of the patrons, in 1618 the chapel underwent reconstruction, which completely changed its structure and dimensions.

Over the years, the Capuchin community founded a small monastery on their lands, which was further expanded through donations from the townspeople. Some bequeathed their property in favor of the brothers of the order. One of these gifts was a building next to the church of Santa Maria della Pace, which was given to the Capuchins after the death of Don Ottavio D'Aragon, one of the wealthy patrons of the order, which made it possible to create a large monastic complex. At the same time, the beginning was made of organizing an underground cemetery in the crypt of the temple, which is currently called the Catacombs of the Capuchins (Catacombe dei Cappuccini), where the first burial took place at the end of the 16th century.

In 1623, the new church building was consecrated as Chiesa Santa Maria della Pace, and became the main church of the monastery.

The Church of Santa Maria della Pace acquired its modern appearance after a major reconstruction in 1934, preserving a huge number of works of art from the 17th – 19th centuries. It consists of three naves, one of which ends with a wide sacristy and choir. The interior of Chiesa Santa Maria della Pace is rich in valuable objects collected by the Capuchins over many decades. These include wooden altars, one of which was carved by a monk in 1854, marble sculptures, a valuable medieval Crucifix, and tombstones over the tombs of the dead, created in the 18th century by local sculptor Ignazio Marabitti.

Only wealthy patrons and defenders of the monastery were buried within the walls of the church; the remains of the deceased brothers, starting from the 16th century, were placed in a common grave located next to the southern side of the temple.

In 1597, it was decided to create a new, more spacious, underground cemetery, which could be entered from the church. A long corridor was made under the main altar, where the remains of forty-five previously deceased monks were transferred. Their bodies were so well preserved that it seemed as if they had been laid to rest several hours ago. This accidental discovery made it possible to create not an ordinary underground cemetery, but the burial Catacombs of the Capuchins, unique in their kind, albeit a little gloomy, which preserved almost incorruptible remains of about eight thousand bodies, divided by gender and belonging to a certain social class.

The first burial in the Catacombs occurred on October 16, 1599, when one of the Capuchin brothers, Silvestro of Gubbio, died, whose remains can be seen in the niche on the left in the corridor of the monks. Other remains of the monks include Riccardo of Palermo, the last Capuchin who was buried in the Catacombs in 1871. The official underground cemetery was closed for burials in 1882, but even after that several more bodies were buried here. One of the last burials dates back to 1920. These are the remains of two-year-old Rosalia Lombardo, who died of a bronchial infection. The baby rests in a small coffin at the foot of the altar in the chapel of St. Rosalia. The girl's embalmed body has been preserved almost incorruptible, and it seems that she is simply sleeping, like Sleeping Beauty.

Over almost three centuries, the Capuchin Catacombs turned into one of the prestigious burial places of Palermo, where not only the Capuchin brothers, but also representatives of the clergy, aristocracy, and bourgeoisie found their final refuge. To accommodate such a number of remains, one corridor was not enough and the Capuchin Catacombs were supplemented with new rooms. Currently, the corridors form a rectangle, in the corners of which there are small rooms - cubicles.

In 1944, the entrance to the underground cemetery was moved from the temple to an adjacent building, standing perpendicular to the Church of Santa Maria della Pace, behind which the “regular” cemetery has been located since the mid-19th century. It was organized after the ban on burials in churches and catacombs. Ordinary townspeople, famous natives of these places, and outstanding people who did a lot for Sicily and Palermo are buried here.

Until 1739, the monks still controlled the filling of the catacombs and issued permission for this or that burial. Then they, apparently, got tired of fighting with the relatives of high-ranking persons and began to bury everyone, until by the end of the 19th century they realized that there was simply no more space.

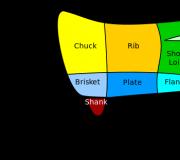

The structure of the Capuchin catacombs consists of several corridors. In the Corridor of the monks, in fact, the novices of the monastery themselves were buried. The bodies of 40 of the most revered monks lie there today, access to which is not allowed to anyone. Next, the Corridor of Men and the Corridor of Women are the burial places of ordinary lay people. In the Kubicul (a room, not a corridor in the catacombs) children are buried for everyone under 14 years of age.

In addition, in the catacombs there is a Corridor of Professionals, in which the most prominent figures in a particular field were buried separately. For example, the Capuchin Catacombs contain the remains of the Spanish artist Diego Velazquez and the sculptor Filippo Pennino. There is also a separate place in the catacombs where virgins were buried.

Today, the Capuchin Catacombs are called the most important attraction of Palermo. They are visited annually by a large number of tourists, however, access is not granted to all premises, and they still do not show particularly creepy mummies. You are not allowed to take photographs in the catacombs, and modern novices of the monastery are increasingly thinking about prohibiting onlookers from entering the catacombs and leaving the mummies alone.

Tombstones and chapels were created by local sculptors and architects Domenico Delisi, Antonio Ugo, Luigi Filippo Labiso, Salvatore Caronia Roberti in the 20th century, whose works can be seen in the city museums and on the streets of Palermo and Mondello.

The cemetery remains active today, preserving the ancient tradition of burial in the Capuchin Monastery, which houses the office of the International College for Religious Missions Abroad and a rich library that has preserved rare editions of books.

If you're in Palermo, include a visit to the Capuchin Catacombs in your itinerary. You can see one of the sights of Palermo for yourself by walking from the historical center of the city.

The main method of preparing bodies for placement in the Catacombs was drying them in special chambers (Collatio) for eight months. After this period, the mummified remains were washed with vinegar, dressed in the best clothes (sometimes, according to wills, the bodies were changed several times a year) and placed directly in the corridors and cubicles of the Catacombs. Some bodies were placed in coffins, but in most cases the bodies were hung, displayed, or laid open in niches on shelves along the walls.

During epidemics, the method of preserving bodies was modified: the remains of the dead were immersed in diluted lime or solutions containing arsenic, and after this procedure the bodies were also put on display.

In 1837, placing bodies in the open was prohibited, but, at the request of the testators or their relatives, the ban was circumvented: one of the walls was removed from the coffins or “windows” were left in the coffins, allowing the remains to be seen.

After the official closure of the Catacombs (1881), several more people were buried here, whose remains were embalmed. The last person to be buried here was Rosalia Lombardo (died December 6, 1920). The doctor who performed the embalming, Alfredo Salafia, never discovered the secret of preserving the body; all that was known was that it was based on chemical injections. As a result, not only the soft tissues of the girl’s face remained incorruptible, but also her eyeballs, eyelashes, and hair. Currently, the secret of the composition has been discovered by Italian scientists studying embalming. Alfredo Salafia's diary was found, which describes the composition: formaldehyde, alcohol, glycerin, zinc salts and salicylic acid. The mixture was supplied under pressure through the artery and dispersed through the blood vessels throughout the body. Studies conducted in the United States on embalming using Salafiya's composition gave excellent results.

The Capuchin Catacombs were considered by the inhabitants of Palermo as a cemetery, albeit an unusual one. Since in the 18th-19th centuries burial here was a matter of prestige, the ancestors of many current residents of Palermo are buried in the Catacombs. The catacombs are regularly visited by descendants of those whose bodies are located here. Moreover, after the official closure of the Catacombs for burials (1882), a “regular” cemetery was built near the walls of the monastery, so the tradition of burial “among the Capuchins” is still preserved.

In various cities and villages of Sicily, the Capuchins created, in imitation of the Palermitan Catacombs, other underground crypts, in which mummified bodies were also exhibited. The most famous of these crypts is the Catacombs of the Capuchins in the town of Savoca (province of Messina), where about fifty mummies of representatives of the local clergy and nobility are kept.

On November 2, 1777, on the day of remembrance of the dead, the poet Ippolito Pindemonte visited the Palermo Catacombs, who, impressed by what he saw, wrote the poem “Tombs” (“Italian: Sepolcri”). In his view, the Catacombs represent a significant triumph of life over death, evidence of faith in the coming Resurrection:

“Large dark underground rooms where in niches, like risen ghosts, stand bodies abandoned by souls, dressed as on the day of their death. From their dead muscles and skin, art has driven away and evaporated every trace of life, so that their bodies and even faces are preserved for centuries. Death looks at them and is horrified by his defeat. When every year the falling autumn leaves remind us of the transience of human life and call us to visit our native graves and shed a tear on them, then a pious crowd fills the underground cells. And in the light of the lamps, everyone turns to the once beloved body and in its pale features looks for and finds familiar features. A son, a friend, a brother finds a brother, a friend, a father. The light of the lamps flickers on these faces, forgotten by Fate, and sometimes seem to tremble... And sometimes a quiet sigh or a restrained sob sounds under the arches, and these cold bodies seem to respond to them. Two worlds are separated by an insignificant barrier, and Life and Death have never been so close."

A hundred years later, Maupassant visited the Catacombs, who described his impressions in “A Wandering Life” (1890). In contrast to the romantic Pindemonte, Maupassant was horrified by what he saw, seeing in the Catacombs a disgusting spectacle of rotting flesh and moribund superstition:

“And suddenly I see in front of me a huge gallery, wide and high, the walls of which are lined with many skeletons dressed in the most bizarre and absurd way. Some hang side by side in the air, others are laid on five stone shelves running from floor to ceiling. A row of dead men stands on the ground in a continuous formation; their heads are scary, their mouths seem to be about to speak. Some of these heads are covered with disgusting vegetation, which further disfigures the jaws and skulls; on others, all the hair was preserved, on others, a tuft of mustaches, on others, part of the beard.

Some look up with empty eyes, others down; some skeletons seem to laugh with a terrible laugh, others seem to writhe in pain, and all of them seem to be enveloped in inexpressible, inhuman horror.

And they are dressed, these dead, these poor, ugly and funny dead, dressed by their relatives, who pulled them out of their coffins to place them in this terrible assembly. Almost all of them are dressed in some kind of black clothes; some have hoods over their heads. However, there are also those whom they wanted to dress more luxuriously - and a pitiful skeleton with an embroidered Greek fez on its head, in the robe of a rich rentier, lies on its back, scary and comical, as if immersed in a terrible dream...

They say that from time to time one or another head rolls to the ground: these are mice chewing through the ligaments of the cervical vertebrae. Thousands of mice live in this storehouse of human meat.

They show me a man who died in 1882. A few months before his death, cheerful and healthy, he came here, accompanied by a friend, to choose a place for himself.

“That’s where I’ll be,” he said and laughed.

His friend now comes here alone and spends hours looking at the skeleton standing motionless in the indicated place...”

Among the celebrities of the 20th century, the French choreographer Maurice Bejart visited the Capuchin Catacombs.

The unique cemetery is one of the most famous attractions of Palermo, attracting many tourists. Although photography and video shooting in the Catacombs is prohibited, several European and American television companies, including NTV, managed to obtain permission to film.

The most famous exhibit of this museum is the little girl Rosalia, who died in 1920 and, at the request of her loving father, was embalmed by the famous necro-make-up artist Alfredo Salafia. The result exceeded all expectations: almost a hundred years have passed, and the girl in the glass coffin simply looks asleep. Her hair, eyelashes, eyebrows were preserved in absolute integrity, and the particularly weak-hearted caretakers of the crypt even started a rumor that the girl opens her eyes at night. You shouldn’t pay attention to this, but it’s very interesting to find out the secret of Salafiya’s magic balm: modern scientists have found that it contained alcohol, formaldehyde, glycerin, zinc and salicylic acid, and the solution was injected directly into the circulatory system. In honor of this girl, the chapel of the Virgin Mary at the monastery was renamed the chapel of St. Rosalia, and the girl is located there.

Monks' corridor

The Corridor of the Monks is historically the most ancient part of the Catacombs. Burials were made here from 1599 to 1871. To the right of the current entrance of the corridor (closed to visitors) are the bodies of 40 of the most revered monks, as well as the following notable persons:

Alessio Narbone - spiritual writer,

Ayala - the son of the Bey of Tunisia, who converted to Christianity and took the name Philip of Austria (died September 20, 1622),

On the left side of the corridor, among other monks, are the bodies of Sylvester of Gubbio (died October 16, 1599), the first to be buried in the Catacombs, and Riccardo of Palermo (died 1871), the last of the Capuchins buried here. All Capuchin bodies are dressed in the robes of their order - a rough cassock with a hood and a rope around the neck.

Corridor of men

The men's corridor forms one of the two long sides of the rectangle. Here, during the 18th-19th centuries, the bodies of the monastery's benefactors and donors from among the lay men were placed. In accordance with the wills of those buried here themselves or the wishes of their relatives, the bodies of the deceased are dressed in a variety of clothes - from a rough funeral shroud like a monastic robe to luxurious suits, shirts, frills and ties.

Children's cubicle

The Children's Cubicle is located at the intersection of the Corridors of Men and Priests. In a small room, the remains of several dozen children are placed in closed or open coffins, as well as in niches along the walls. In the central niche there is a children's rocking chair, on which sits a boy holding his younger sister in his arms.

The remains, turned into skeletons, make an amazing contrast with the children's suits and dresses lovingly chosen by their parents, as noted by Maupassant in “A Wandering Life.”

...We come to a gallery full of small glass coffins: these are children. The barely strengthened bones could not stand it. And it’s hard to see what actually lies in front of you, they are so mutilated, flattened and terrible, these pathetic children. But tears come to your eyes because their mothers dressed them in the little dresses they wore in the last days of their lives. And mothers still come here to look at them, at their children!

Women's corridor

The women's corridor forms one of the smaller sides of the rectangle. Until 1943, the entrance to this corridor was closed by two wooden bars, and the niches with bodies were protected by glass. As a result of Allied bombing in 1943, one of the gratings and glass barriers was destroyed and the remains were significantly damaged.

Most of the women's bodies placed here lie in separate horizontal niches, and only a few of the best preserved bodies are placed in vertical niches. The women's bodies are dressed in the best clothes according to the fashion of the 18th-19th centuries - silk dresses with lace and frills, hats and caps. The shocking discrepancy between the remains, scattered over time, and the flashy fashionable outfits in which they are dressed, was noticed by Maupassant.

Here are women who are even more monstrously comical than men, because they are coquettishly dressed up. Empty eye sockets look at you from under lace caps decorated with ribbons, framing with their dazzling whiteness these black faces, terrible, rotten, corroded by decay. The arms stick out from the sleeves of the new dresses, like the roots of felled trees, and the stockings that fit the bones of the legs seem empty. Sometimes the deceased wears only shoes, huge on his pitiful, withered feet.

Cubicula of virgins

A small cubicula, located at the intersection of the Corridors of Women and Professionals, is reserved for the burial of girls and unmarried women. About a dozen bodies lie and stand near a wooden cross, above which is placed the inscription “These are those who have not defiled themselves with their wives, for they are virgins; these are they who follow the Lamb wherever he goes” (Rev. 14:4). The heads of the girls are crowned with metal crowns as a sign of the virgin purity of the deceased.

New corridor

The new corridor is the most recent part of the Catacombs, used after the ban on displaying the bodies of the dead (1837). As a result of this ban, there are no wall niches in the corridor. The entire space of the corridor was gradually (1837-1882) filled with coffins. As a result of the bombing on March 11, 1943 and the fire of 1966, most of the coffins were destroyed. Currently, the surviving coffins are placed along the walls in several rows, so that in the central part of the corridor you can see the floor decorated with majolica. In addition, in the New Corridor you can see several “family groups” - the bodies of the father and mother of the family with their several teenage children are exhibited together.

Corridor of professionals

Bodies of two military men (Francesco Enea - bottom)

The Professionals' Corridor, running parallel to the Men's Corridor, forms one of the two long sides of the rectangle. The bodies of professors, lawyers, artists, sculptors, and professional military men are placed in this corridor. Notable among those buried here are:

Filippo Pennino - sculptor,

Lorenzo Marabitti - sculptor who worked, among other things, in the cathedrals of Palermo and Monreale,

Salvatore Manzella - surgeon,

Francesco Enea (died 1848) - Colonel, lying in a superbly preserved military uniform of the army of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

According to local legend, accepted or rejected by various researchers, the body of the Spanish painter Diego Velazquez rests in the Corridor of Professionals.

Priests' Corridor

Parallel to the Corridors of Friars and Women, there is an additional corridor in which numerous bodies of priests of the Diocese of Palermo are placed. The bodies are dressed in multi-colored liturgical vestments, contrasting with the withered mummies. In a separate niche is placed the body of the only prelate buried in the Catacombs - Franco d'Agostino, Bishop of Piana degli Albanesi (Italo-Albanian Catholic Church).

HGIOLLocation

The Capuchin Catacombs are located under the Capuchin Monastery (Italian: Convento dei Cappuccini) outside the historical center of Palermo. From Piazza Independentza(Norman and Orleans palaces) you need to walk along Corso Calatafimi two blocks and then turn down Via Pindemonte. The specified street ends with a square Piazza Cappuccini, on which the monastery building is located.

Story

Initially, the entrance to the Catacombs was carried out directly from the monastery church located above. In 1944, a new entrance was opened directly from Piazza Cappuccini.

For practical reasons, the entrance to the “dead-end” corridors and cubicles is blocked by bars, and the movement of visitors is organized around the perimeter of the rectangle.

Monks' corridor

- Don Vincenzo Agati(died April 3, 1731).

On the left side of the corridor, among other monks, bodies are placed Sylvester of Gubbio(died October 16, 1599), the first of those buried in the Catacombs, and Riccardo from Palermo(died 1871), the last of the Capuchins to be buried here. All Capuchin bodies are dressed in the robes of their order - a rough cassock with a hood and a rope around the neck.

Corridor of men

The men's corridor forms one of the two long sides of the rectangle. Here, during the 18th and 19th centuries, the bodies of the monastery's benefactors and donors from among the lay men were placed. In accordance with the wills of those buried here themselves or the wishes of their relatives, the bodies of the deceased are dressed in a variety of clothes - from a rough funeral shroud like a monastic robe to luxurious suits, shirts, frills and ties.

Children's cubicle

The Children's Cubicle is located at the intersection of the Corridors of Men and Priests. In a small room, the remains of several dozen children are placed in closed or open coffins, as well as in niches along the walls. In the central niche there is a children's rocking chair, on which sits a boy holding his younger sister in his arms.

The remains, turned into skeletons, make an amazing contrast with the children's suits and dresses lovingly chosen by their parents, as noted by Maupassant in “A Wandering Life.”

...We come to a gallery full of small glass coffins: these are children. The barely strengthened bones could not stand it. And it’s hard to see what actually lies in front of you, they are so mutilated, flattened and terrible, these pathetic children. But tears come to your eyes because their mothers dressed them in the little dresses they wore in the last days of their lives. And mothers still come here to look at them, at their children!

Women's corridor

The women's corridor forms one of the smaller sides of the rectangle. Until 1943, the entrance to this corridor was closed by two wooden bars, and the niches with the bodies were protected by glass. As a result of Allied bombing in 1943, one of the gratings and glass barriers was destroyed and the remains were significantly damaged.

Most of the women's bodies placed here lie in separate horizontal niches, and only a few of the best preserved bodies are placed in vertical niches. The women's bodies are dressed in the best clothes according to the fashion of the 18th and 19th centuries - silk dresses with lace and frills, hats and caps. The shocking discrepancy between the remains that have crumbled over time and the flashy fashionable outfits in which they are dressed was noted by Maupassant.

Here are women who are even more monstrously comical than men, because they are coquettishly dressed up. Empty eye sockets look at you from under lace caps decorated with ribbons, framing with their dazzling whiteness these black faces, terrible, rotten, corroded by decay. The arms stick out from the sleeves of the new dresses, like the roots of felled trees, and the stockings that fit the bones of the legs seem empty. Sometimes the deceased is wearing only shoes, huge on his pitiful, withered feet.

Cubicula of virgins

A small cubicula, located at the intersection of the Corridors of Women and Professionals, is reserved for the burial of girls and unmarried women. About a dozen bodies lie and stand near a wooden cross, above which is placed the inscription “These are those who have not defiled themselves with their wives, for they are virgins; these are they who follow the Lamb wherever he goes” (Rev.). The girls' heads are crowned with metal crowns as a sign of the virgin purity of the deceased.

New corridor

The new corridor is the most recent part of the Catacombs, used after the ban on displaying the bodies of the deceased (). As a result of this ban, there are no wall niches in the corridor. The entire space of the corridor was gradually (1837-) filled with coffins. As a result of the bombing on March 11, 1943 and the fire of 1966, most of the coffins were destroyed. Currently, the surviving coffins are placed along the walls in several rows, so that in the central part of the corridor one can see the floor decorated with majolica. In addition, in the New Corridor you can see several “family groups” - the bodies of the father and mother of the family with their several teenage children are exhibited together.

Corridor of professionals

The Professionals' Corridor, running parallel to the Men's Corridor, forms one of the two long sides of the rectangle. The bodies of professors, lawyers, artists, sculptors, and professional military men are placed in this corridor. Notable among those buried here are:

- Filippo Pennino- sculptor,

- Lorenzo Marabitti- sculptor who worked, among other things, in the cathedrals of Palermo and Monreale,

- Francesco Enea(died 1848) - Colonel, lying in a superbly preserved military uniform of the Army of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

According to local legend, accepted or rejected by various researchers, the body of the Spanish painter Diego Velazquez rests in the Corridor of the Professionals.

Priests' Corridor

Parallel to the Corridors of Friars and Women, there is an additional corridor in which numerous bodies of priests of the Diocese of Palermo are placed. The bodies are dressed in multi-colored liturgical vestments, contrasting with the withered mummies. In a separate niche is placed the body of the only prelate buried in the Catacombs - Franco D'Agostino, Bishop of Piana degli Albanesi (Italo-Albanian Catholic Church).

Chapel of Saint Rosalia

The most famous part of the Catacombs is the chapel of Saint Rosalia (until 1866 it was dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows). In the center of the chapel, the body of one-year-old Rosalia Lombardo (died 1920) rests in a glass coffin. As a result of the success, other underground Sepolcri were created in imitation of the Palermitan Catacombs." In his view, the Catacombs represent a significant triumph of life over death, evidence of faith in the coming Resurrection:

“Large dark underground rooms where in niches, like risen ghosts, stand bodies abandoned by souls, dressed as on the day of their death. From their dead muscles and skin, art has driven away and evaporated every trace of life, so that their bodies and even faces are preserved for centuries. Death looks at them and is horrified by his defeat. When every year the falling autumn leaves remind us of the transience of human life and call us to visit our native graves and shed a tear on them, then a pious crowd fills the underground cells. And in the light of the lamps, everyone turns to the once beloved body and in its pale features looks for and finds familiar features. A son, a friend, a brother finds a brother, a friend, a father. The light of the lamps flickers on these faces, forgotten by Fate, and sometimes seem to tremble...

And sometimes a quiet sigh or a restrained sob sounds under the arches, and these cold bodies seem to respond to them. Two worlds are separated by an insignificant barrier, and Life and Death have never been so close."

A hundred years later, the Catacombs were visited by Maupassant, who described his impressions in “A Wandering Life” (). In contrast to the romantic Pindemonte, Maupassant was horrified by what he saw, seeing in the Catacombs a disgusting spectacle of rotting flesh and moribund superstition:

“And suddenly I see in front of me a huge gallery, wide and high, the walls of which are lined with many skeletons dressed in the most bizarre and absurd way. Some hang side by side in the air, others are laid on five stone shelves running from floor to ceiling. A row of dead men stands on the ground in a continuous formation; their heads are scary, their mouths seem to be about to speak. Some of these heads are covered with disgusting vegetation, which further disfigures the jaws and skulls; on others, all the hair was preserved, on others, a tuft of mustaches, on others, part of the beard.

Some look up with empty eyes, others down; some skeletons seem to laugh with a terrible laugh, others seem to writhe in pain, and all of them seem to be enveloped in inexpressible, inhuman horror.

And they are dressed, these dead, these poor, ugly and funny dead, dressed by their relatives, who pulled them out of their coffins to place them in this terrible assembly. Almost all of them are dressed in some kind of black clothes; some have hoods over their heads. However, there are also those whom they wanted to dress more luxuriously - and a pitiful skeleton with an embroidered Greek fez on its head, in the robe of a rich rentier, lies on its back, scary and comical, as if immersed in a terrible dream...

They say that from time to time one or another head rolls to the ground: these are mice chewing through the ligaments of the cervical vertebrae. Thousands of mice live in this storehouse of human meat.

They show me a man who died in 1882. A few months before his death, cheerful and healthy, he came here, accompanied by a friend, to choose a place for himself.

“That’s where I’ll be,” he said and laughed.There are so many museums on our planet! But the most unusual is the famous Catacombe dei Cappuccini, the exhibits of which will shock the unprepared visitor. This is not just a museum, but a real elite cemetery where more than eight thousand mummies are buried.

The most unusual catacombs in the world

Let's figure out what the word "catacombs" means. It comes from the Latin catacumbae, which translates to “to go to bed.” In Western Europe, underground labyrinths have always been associated with burial places for the dead. In the 16th century, the monastic order of the Capuchins, established by the Pope, operated, whose members were engaged in missionary work, preaching Christianity throughout the world.

The largest community was in Palermo, Sicily. The Capuchin catacombs appeared at the end of the 16th century, when there were too many dead. It was then that the question of a new burial place arose. Members of the order remembered the crypt - a huge basement room located in the Convento dei Cappuccini monastery, where it was decided to place the bodies of the dead. In 1599, the world-famous catacombs appeared, and their unusual feature was that the deceased were buried not in coffins, but in the open. Permits for burial were issued by city archbishops or monastery abbots.

Embalming, which allowed bodies to be preserved

In underground tombs, the bodies decomposed very slowly; in addition, they were dried in special chambers for several months, the remains were washed with vinegar, embalmed and dressed in the best clothes. They were then displayed openly on shelves that ran along the walls.

When terrible epidemics began in the city, the method of preserving bodies changed slightly: the remains were placed in special vessels filled with a solution of arsenic, and only after this procedure were they laid out for public display.

Elite cemetery

Initially, the Capuchin catacombs were intended only for members of the monastic order, but over time they turned into a prestigious cemetery where the noble people of Palermo wanted to be buried. In their wills, the rich patrons of the monastery discussed all the points, prescribing at what intervals clothes should be changed.

And soon the elite cemetery began to exist on donations from relatives of the deceased, who could come on certain days to touch the hands of departed loved ones and pray. Each body was kept in a permanent place, but as soon as the family stopped paying money, the corpse was moved further away.

The last shelter for 8 thousand citizens

Soon the basement becomes cramped and the monks begin to dig additional underground corridors, which now form a rectangle. The Capuchin Catacombs were closed by the authorities in 1882, after existing for 283 years. Over such an impressive period of time, about eight thousand rich and respected residents of Palermo found their final refuge in them. According to rough estimates, almost 30 dead people were buried in the Catacombe dei Cappuccini per year.

When it was forbidden to place bodies in the open, the monks removed one of the walls in the coffin, leaving “windows” for family members to see the remains.

Catacomb structure

Structurally, the gloomy Capuchin catacombs in Palermo consist of several underground corridors. All the halls of the world's largest necropolis of mummies are divided into separate categories: the dead differ not only by gender, but also by belonging to social strata of society. In one of the rooms lie the bodies of respected monks, where access to visitors is prohibited. This is followed by corridors where men and women are buried, and children under 14 years old are buried in a cubicle - a small room underground. Prominent residents of the city and virgins were buried separately.

Corridors

The monks' corridor is the oldest part of the dungeons, where the most revered Capuchins are buried. All of them are buried in the clothes of their order - a rough cassock with a rope wound around the neck. The bodies of the dead priests of Palermo, dressed in bright vestments, were in a separate room.

Until 1943, the entrance to the women's corridor was closed with bars, and the bodies were kept in niches under sealed glass. However, as a result of the bombing, the barriers were destroyed and the remains were seriously damaged. Now only some of the bodies are placed in vertical niches, while the rest lie. Turned into dust over time, they present a terrifying sight: empty eye sockets look out from under hats that were fashionable at the time, and bony arms stick out from the sleeves of silk dresses.

The order's wealthy lay patrons found their final resting place in the corridor of men, and the bodies of famous sculptors, surgeons, military men, artists, and lawyers rest in the corridor of professionals. According to unconfirmed reports, the Capuchin catacombs contain the body of Velazquez, the famous Spanish painter.

After the ban on putting corpses on public display, another corridor appeared in the cemetery, which was filled with closed coffins. In 1943, most of them were destroyed. Now here you can see the floor decorated with majolica (colored ceramics made of clay), as well as the bodies of a married couple with two babies displayed together.

Cubes

The remains of the children were placed in a cubicula. Here, boys and girls lie in open and closed coffins, and their bodies are laid in niches running along the walls. In the center of the room, a child sits on a rocking chair, holding his younger sister close to him. Tourists have tears in their eyes when they see the skeletons of children dressed in cute dresses and suits.

Another small cubicula is reserved for the burial of dead virgins. Near the wooden cross located in the center of the room rest a dozen bodies of girls, on whose heads there are metal crowns, symbolizing the purity of the deceased.

The beautiful inhabitant who made the Capuchin catacombs famous

The girl Rosalia Lombardo is the last person buried after the official closure of the elite cemetery by the authorities and the most famous exhibit of the unusual museum. She died in December 1920, before reaching the age of two. The father, who was grieving the terrible loss, asked to have his baby embalmed to prevent decomposition of the body. Unfortunately, no official documents telling about the girl herself have been preserved, just as there are no photographs of living Rosalia, who was a very sickly child.

The famous master A. Salafiya, who mastered effective embalming technology, fulfilled the request of the inconsolable parents. The solution, which included alcohol, zinc salts, formalin, glycerin and other chemical compounds, dispersed through the blood vessels, which allowed the girl’s body, which was in a glass coffin in the far part of the dungeons, to be perfectly preserved. The soft tissues of the face, eyeballs, eyelashes and hair remained imperishable.

Scandals associated with the baby's name

Almost a hundred years later, the child's mummy, placed in the Capuchin catacombs, looks fresh and natural, sparking talk of replacing the girl's body, which has turned to dust, with a wax replica. To refute the rumors, special equipment was brought here to illuminate the coffin. Researchers saw the child's skeleton, his brain and organs, which turned out to be intact. And after the release of a documentary film about Rosalia, all rumors stopped. Viewers examined the baby's body not only from the outside, but also inside the coffin, and were also shown hands resting under the blanket, which no one had seen before.

The little sleeping beauty excites people's imagination, and a few years ago, after her eyes opened slightly, real hysteria began. Excited tourists said that her spirit had returned to the baby’s body, and scientists who noticed strange temperature changes in the basement named them as the cause of the phenomenon that caused fear among people.

The mummy of an innocent child, which often exudes a pleasant scent of lavender, attracts huge numbers of visitors and has been a source of inspiration for many creative people for a century. In honor of the baby, the ancient religious building at the monastery was renamed, and now the girl is in the chapel of St. Rosalia.

Regularly, the descendants of those who rest in the dungeons of Palermo visit the Capuchin catacombs, photos of which terrify many. After the official closure of the necropolis, a regular cemetery appeared near the walls of the monastery, and members of the order created underground crypts in other settlements, and the most famous are the structures in the city of Savoca, where about 150 mummies of the local nobility and clergy are located.

At the end of the 18th century, Palermo was visited by the famous poet I. Pindemonte, who was so impressed by the catacombs that he dedicated the poem Sepolcri ("Tombs") to them. In it he sang about the triumph of life over death and faith in the resurrection of man.

A hundred years later, Maupassant looked into the gloomy burial catacombs of the Capuchins in Italy, but the sight he saw caused him real horror. Unlike the romantically inclined poet, he noticed rotting flesh, disgusting skeletons dressed in the most ridiculous way, and mice gnawing cervical vertebrae...

Where is the necropolis located?

Finding this place is very simple: the underground crypts are located within the city, on Piazza Cappuccini, building 1. It is here that the famous monastery is located, storing the bodies of the inhabitants. The cost of visiting the museum, where the mummies of the deceased are fenced off, is 1.5 euros.

What do tourists say?

Tourists who have visited the burial catacombs of the Capuchins in Palermo admit that this sight is not for the faint of heart. Dressed up skeletons with empty eye sockets and dried up mummies leave a depressing impression. And many of those who visited the dungeon did not feel Easter joy. They wanted to quickly leave the kingdom of the dead, where everything is saturated with grief, and death is presented in a very ugly form. However, for the residents of Palermo, the creepy place is the most ordinary cemetery, and they do not feel any fear.

The funerary catacombs of the Capuchins, in which the monks clearly showed everyone what awaited people in the future, are one of the main attractions of the Italian city. Hundreds of thousands of onlookers visit them every year, but not all rooms of the creepy necropolis can be accessed. Photography is prohibited here, but some tourists still manage to take pictures. Recently, there has been more and more talk about banning access to underground corridors and finally leaving in peace those who died many centuries ago.

Catacombs of the Capuchins (Palermo, Italy) - exhibitions, opening hours, address, phone numbers, official website.

- Tours for May to Italy

- Last minute tours to Italy

Previous photo Next photo

On the Italian island of Sicily, formed as a result of volcanic activity in the Mediterranean Sea, somewhere outside the historical center of Palermo, under the Capuchin monastery there is one of the most extraordinary museums of our time - the Capuchin Catacombs. Located in the square of the same name, Piazza Cappuccini, the catacombs are underground funerary galleries and are the extensive burial grounds of Sicilian nobility from the 16th to 19th centuries.

This “mass” tomb is one of the most famous mummies exhibits today. The branched corridors of the catacombs are divided into sections: halls of men, women and children, a hall of maidens, priests and monks, as well as representatives of various professions, in the last of which rests the remains of the famous Spanish painter Diego Velazquez.

Finding yourself in this huge dungeon, you are amazed at how cleverly the space around is organized - not a single free centimeter! Walking along the corridors and meeting the eyes of the visitors who wandered here, I read on their faces either terrible disgust or undisguised delight.

Skeletonized, mummified and embalmed bodies of the deceased lie, stand and even hang along the walls. They are dressed in clothes that easily reflect the fashion of those times. But the most interesting question is, why were they buried here? And why are they put on public display? There is a version that in the 16th century, Capuchin monks discovered in the cellar of the monastery a certain preservative contained in the air, which helps to embalm the bodies of the dead. Since then - since 1599 - with the permission of the prelates, the first burials of monks have been made here, but after 1739, due to the massive popularity of this “cemetery”, consent was given by the abbot of the monastery. This is how the catacombs became the most prestigious burial place until the end of the 19th century. Much water has passed under the bridge since then, but many mummies are still in excellent condition to this day. In general, this place is not for the faint of heart, but for extreme sports enthusiasts who love originality.

With the growing popularity of “catacombs,” additional methods began to be used in the burial process, which, in addition to the “special” composition of the air, contributed to better preservation of bodies. When embalming the deceased girl Rosalia Lombardo, the “know-how” of the Palermitan doctor Alfredo Salafia was used. When you look at Rosalia, you get the impression that the child is sleeping in a serene sleep - her face looks so “alive”. Thus, Rosalia’s mummy received the nickname “Sleeping Beauty”, and her burial became one of the last in the history of the catacombs.

The first emotion that visited me in the tomb was surprise, bordering on irritation and a certain amount of anger. There is an odor of disrespect and disregard for the remains of once-living people. After all, they are just exhibits, another “attraction” for tourists.

Finding yourself in this huge dungeon, you are amazed at how cleverly the space around is organized - not a single free centimeter! Walking along the corridors and meeting the eyes of the visitors who wandered here, I read on their faces either terrible disgust or undisguised delight. To tell the truth, the aura here was hardly benevolent, and yet someone even managed to take photographs, despite the warning prohibitions!

The catacombs owe their popularity to Italian, French and German writers, who made them one of the most popular places in Europe and America. This is what museums are like!

Practical information

- Address: Piazza Cappuccini 1

- Opening hours: daily, from 9:00 to 13:00 and from 15:00 to 18:00. The catacombs are closed on Sundays from late October to late March.

- Entrance fee: 3 EUR; Photos and video prohibited. Prices on the page are as of September 2018.

In the catacombs under the Capuchin monastery in Palermo, a real city of the dead was discovered.

Five centuries ago, the dungeon of an ancient monastery began to be used as a necropolis for the burial of residents of an Italian city. About 2000 inhabitants of this terrible place terrify the guests of the tomb, looking at them with the empty eye sockets of ancient skulls.

The bodies are located in a variety of poses and sometimes one gets the impression that there is something alive in them...

The oldest in the catacombs is more than 4 centuries old. This is the monk Silvestro Subbio, who died in 1599, and is buried in the traditional monastic habit.

The most recent burial in the catacombs dates back to 1920. The two-year-old girl Rosalina, who died of a bronchial infection, found her final refuge there. Despite the fact that more than 90 years have passed since her death, the girl looks as if she had recently fallen asleep.

Why the mummification masters so skillfully decided to preserve only this body remains a mystery. From the other dead, only bones with small elements of flesh or hair remained.

Using surviving manuscripts, scientists were able to reconstruct the original embalming process. The deceased was dissected, the organs were removed and the body was left to dry. After 7-8 months, it was dipped in vinegar, after which it was placed in a coffin or hung on the wall - it all depended on the wishes of the relatives.

The catacombs are divided into several sections. One of them contains mummies of priests, the other belongs entirely to women, whose corpses in half-decayed skirts and with torn sun umbrellas in their hands look especially creepy. The virgins are buried separately.

There is also a children's room in the dungeon. The untimely departed little ones rest here in their best clothes. Among them is little Rosalina, whom locals have long considered a doll. However, researchers have proven that the girl's body was mummified using ancient chemicals, which allowed it to be so well preserved.

In various cities and villages of Sicily, the Capuchins created, in imitation of the Palermitan Catacombs, other underground crypts, in which mummified bodies were also exhibited. The most famous of these crypts is the Catacombs of the Capuchins in the town of Savoca, where about fifty mummies of representatives of the local clergy and nobility are kept.

The study of ancient mummies has allowed scientists to learn a lot about diseases and life expectancy of people in past centuries.

Video - Catacombs in Palermo